Inclusion as a Facilitator of Social and Physical Activity for People with Physical Disabilities

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Theoretical & Conceptual Frameworks

2.2. Participants

2.3. Data Generation

2.4. Data Analysis

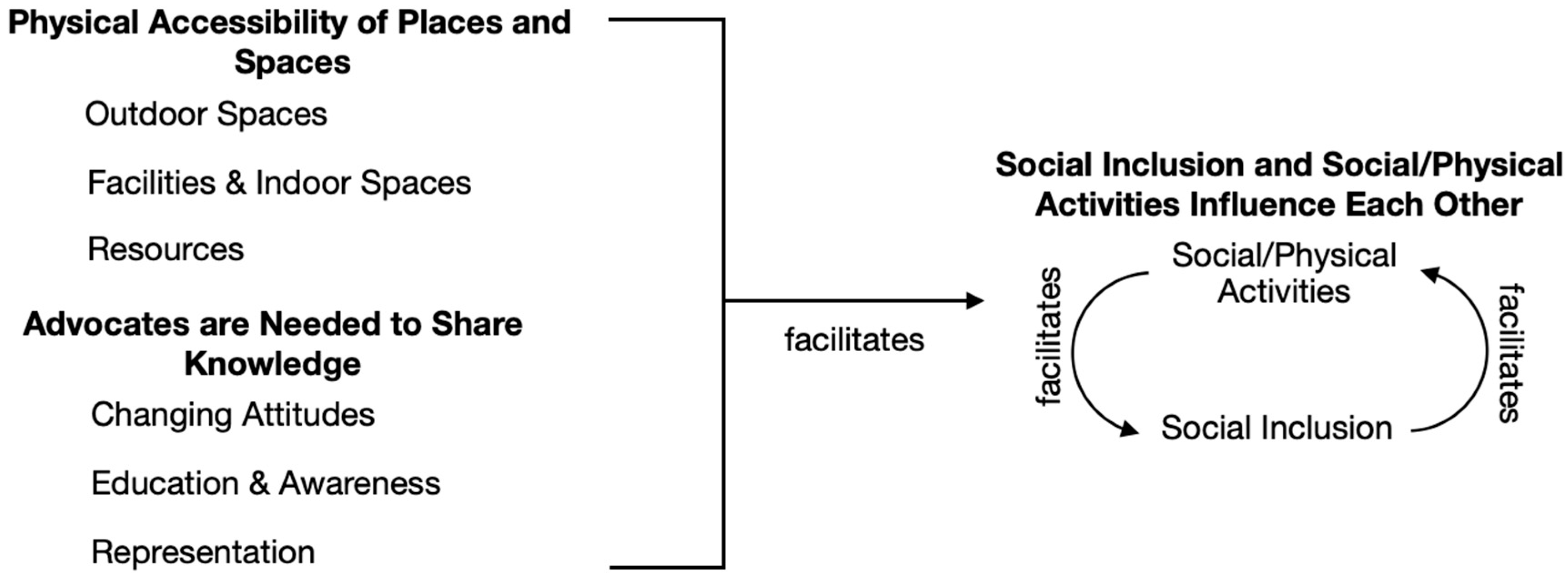

3. Results

3.1. Physical Accessibility of Spaces and Places

Direct physical activity is hard because I have no mobility below my shoulders … there’s a lot of trails and stuff that I would still like to do, but it’s difficult to make sure the lift works anymore, so I am limited in my social interactions with my friends too, like there’s only specific places that we can go.

3.1.1. Facilities and Indoor Spaces

The wheelchair access was in the back alley, which was a potholed kinda surface on the asphalt, but a beautiful new ramp to get into this renovated building. And the problem, when you go up the ramp in your chair, when you get to the top it isn’t an electric door … [when you] pull [the door] out, you couldn’t because you’re on a ramp. So you had to back your chair up and stretch forward as far as you could … and then there was a [significant] gap to get into the door.

I’m the only one in a wheelchair so I have the best knowledge of situations where you have to roll around into … we just discussed [ways to] make the things more accessible in our community … that would assure that it was easier to get around … I think it’s very important to be engaged in the community to help them more or less understand my point of view.

Downtown at [a social location] they have a parking spot right in front of the ramp and there’s always a truck blocking it, so I went and told them that and within three days they put up a handicap parking sign to open up that area, so that was really nice, they were super quick to respond.

3.1.2. Outdoor Spaces

I mean, buildings could be, it’s more accessible but that’s an ongoing need, but municipalities could make their trails [more accessible] and people in wheelchairs would gladly go around to things if they could … people in wheelchairs in particular, we have a tendency to think it’s all inaccessible, we can’t do any of it … well it could be accessible if there was a bunch of people who helped with it right?

3.1.3. Availability of Resources

At least making an effort to make—even places that aren’t … accessible, more accessible … getting … little ramps to help go over curbs. … Maybe when you’re building … a building, you know making your doors [wider]. I think doing that—or being open to, you know, having … both doors open. The little things like installing a button.

Accessibility is a big factor … with the planning and physical structure … it can be the location, the lack of transportation, the access route to get to where you need to go, the lack of snow clearing, … the time of day, … even the cost, for many people that are living on low income, it’s not just disability—there’s many factors that kind of perpetuate the exclusion of others.

3.2. Advocates Are Needed to Share Knowledge

Being in groups, talking to people, being in a lot of groups and helping whenever you can … if you’re engaged, you’re going to events … maybe weekly clubs or weekly practices and weekly different groups that you go to help build your community … I learned a lot of my assets and my independence from different people throughout my [adapted sports] career … they could come out to practice and see how these people function … so that they can share the same independence a lot of these people do.

[community organization] they oversee a lot of community events and are invited to community events … So just having those community ties … it’s very nice to have part of the community and people actively looking out … for your interests and removing your barriers.

3.2.1. Representation in Organizations and Programs

I would use like the social system here if there was one, I wish there was such a way to find what is available athletically here for me … you need somebody that has [a physical disability] to come in and speak to you, it doesn’t, you know, having a social worker come in and go, I understand, well no, you don’t, you’ve got [no physical disability], we have to have somebody there that’s [got a physical disability] … there’s no group leading for people that have disabilities to come together and to do something as a group … we can build a community within the community and then make people stronger and feeling more confident about coming out and doing things and being more visible and not just hiding.

3.2.2. Education and Awareness

There’s a way to get people to become more educated so that they can reduces some of the education for the person who has the disability … and in general to recognize that we’re all part of the community, we need to make changes and adaptations to the environment and our belief system to help people become more inclusive, because we’re all a valuable part of it right?—Ron

… but it’s making people aware and educating them the importance of physical activity for people with disabilities. It may look different how we engage in, in physical activity—but there are ways—it’s just looking outside of the box and the power to be looking outside the box on how they can be more able to make it more [accessible].—Linda

3.2.3. Changing Attitudes

I’ve had a lot of looks, I mean I’ve had [an elderly women] say to me ‘you should not be out here looking like that’ … people would want to hide … and just stating well I have a right be here in this community just as much as you do, and I think it’s what needs to start happening you know … because I think it’s a fear reaction because of how people have been treated through the years, because you’ve got that mentality that’s been brought forth from the past that people with [physical disabilities] are stupid or are not capable of doing things … and that’s discrimination … that’s not who I am, that’s not how, you know, I am not viewed as my disability.

What we need in the community—we just keep being visual … we need to show people that we want to be out in our … communities … because I think that’s what’s important to our quality of life as well. I heard comments that ‘oh well, you don’t see many of those people in wheelchairs, so why would we make changes?’ Well, it’s not just those people in the wheelchairs—it’s for everyone that we’re wanting to make these changes [for]. If the ramp is easier for a person with a cane, or a senior, or … for delivery people. Rather than having to bump up stairs. We’re not just being out there … for people who have disabilities throughout their community … it’s the education and the awareness that we have to do … it’s the biggest thing.—Linda

3.3. Social Inclusion and Social/Physical Activity Influence Each Other

I think it’s just very important to be socially involved in any [sports and physical activities] and I think it’s good for anyone’s physical health to be involved in those things … and [their] emotional health.

3.3.1. Social Inclusion Facilitates Social/Physical Activities

The social and community ties are important for anybody just to be able to get through life in general because it’s really hard if you’re socially isolated … because it’s affecting your mental health as well … and the more you’re involved in the community with social ties and what not then you start getting more involved in the physical activities that are in the community or available, because if you’re [socially isolated] you’re not gonna be aware of some of the things that are out there.

3.3.2. Social/Physical Activities Facilitate Social Inclusion

I got involved in some things some sports related stuff like martial arts … and just getting out there and getting connected opened up a lot more physical activities and social opportunities that I didn’t have previously.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Disability Language/Terminology Positionality Statement

Abbreviations

| BC | British Columbia |

| SCI BC | Spinal Cord Injury BC |

References

- World Health Organization. Global Report on Health Equity for Persons with Disabilities; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, S.P.; Fawcett, G.; Brisebois, L.; Hughes, J. Canadian Survey on Disability Reports: A Demographic, Employment, and Income Profile of Canadians with Disabilities Aged 15 Years and Over, 2017; No. 89-654-X; Statistics Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Downer, M.B.; Rotenberg, S. Disability—A chronic omission in health equity that must be central to Canada’s post-pandemic recovery. Health Promot. Chronic Dis. Prev. Can. 2023, 43, 348–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilcher, S.J.T.; Craven, B.C.; Bassett-Gunter, R.L.; Cimino, S.R.; Hitzig, S.L. An examination of objective social disconnectedness and perceived social isolation among persons with spinal cord injury/dysfunction: A descriptive cross-sectional study. Disabil. Rehabil. 2019, 43, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jehn, A.; Zajacova, A. Disability trends in Canada: 2001–2014 population estimates and correlates. Can. J. Public Health 2019, 110, 354–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usama, S.M.; Kothari, Y.L.; Karthikeyan, A.; Khan, S.A.; Sarraf, M.; Nagaraja, V. Social isolation, loneliness, and cardiovascular mortality: The role of health Care system interventions. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 2024, 26, 669–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steptoe, A.; Shankar, A.; Demakakos, P.; Wardle, J. Social isolation, loneliness, and all-cause mortality in older men and women. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 5797–5801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beller, J.; Wagner, A. Loneliness, social isolation, their synergistic interaction, and mortality. Health Psychol. 2018, 37, 808–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurung, S.; Jenkins, H.T.; Chaudhury, H.; Ben Mortenson, W. Modifiable sociostructural and environmental factors that impact the health and quality of life of people with spinal cord injury: A scoping review. Top. Spinal Cord Inj. Rehabil. 2023, 29, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heeb, R.; Putnam, M.; Keglovits, M.; Weber, C.; Campbell, M.; Stark, S.; Morgan, K. Factors influencing participation among adults aging with long-term physical disability. Disabil. Health J. 2022, 15, 101169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turcotte, S.; Kheroua, S.; Brun, G.; Gagnon, L.; Bustamante, N.; Labbé, A.; Simard, P.; Veilleux, M.; Lapointe, M.; Nguyen, M.H.; et al. Barriers and Facilitators to the Social Participation of Individuals Aging with a Long-Term Neurological Disability: A Scoping Review. Disabilities 2025, 5, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginis, K.A.; van der Ploeg, H.P.; Foster, C.; Lai, B.; McBride, C.B.; Ng, K.; Pratt, M.; Shirazipour, C.H.; Smith, B.; Vásquez, P.M.; et al. Participation of people living with disabilities in physical activity: A global perspective. Lancet 2021, 398, 443–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginis, K.A.M.; Evans, M.B.; Mortenson, W.B.; Noreau, L. Broadening the conceptualization of participation of persons with physical disabilities: A configurative review and recommendations. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2017, 98, 395e402. [Google Scholar]

- Brady, R.; Brown, W.J.; Hillsdon, M.; Mielke, G.I. Patterns of accelerometer-measured physical activity and health outcomes in adults: A systematic review. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2022, 54, 1155–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelletier, C. Exercise prescription for persons with spinal cord injury: A review of physiological considerations and evidence-based guidelines. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2023, 48, 882–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, K.R.; Lawrason, S.V.; Shaw, R.B.; Wirtz, D.; Martin Ginis, K.A. Physical activity interventions, chronic pain, and subjective well-being among persons with spinal cord injury: A systematic scoping review. Spinal Cord 2021, 59, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santino, N.; Larocca, V.; Hitzig, S.L.; Guilcher, S.J.; Craven, B.C.; Bassett-Gunter, R.L. Physical activity and life satisfaction among individuals with spinal cord injury: Exploring loneliness as a possible mediator. J. Spinal Cord Med. 2020, 45, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasiemski, T.; Brewer, B.W. Athletic identity, sport participation, and psychological adjustment in people with spinal cord injury. Adapt. Phys. Act. Q. 2011, 28, 233–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javorina, D.; Shirazipour, C.H.; Allan, V.; Latimer-Cheung, A.E. The impact of social relationships on initiation in adapted physical activity for individuals with acquired disabilities. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2020, 50, 101752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knibbe, T.J.; Biddiss, E.; Gladstone, B.; McPherson, A.C. Characterizing socially supportive environments relating to physical activity participation for young people with physical disabilities. Dev. Neurorehabilit. 2017, 20, 294–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knibbe, T.J.; Biddiss, E.; Gladstone, B.; McPherson, A.C. Feasibility and short-term effects of Activity Coach+: A physical activity intervention in hard-to-reach people with a physical disability. Disabil. Rehabil. 2020, 43, 2769–2778. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, R.A.; McKenzie, G.; Holmes, C.; Shields, N. Social Support Initiatives That Facilitate Exercise Participation in Community Gyms for People with Disability: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 20, 699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations. Chapter 1: Identifying Social Inclusion and Exclusion in Leaving no One Behind: The Imperative of Inclusive Development: Report on the World Social Situation 2016; United Nations: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, R.; Waterfield, J. Making words count: The value of qualitative research. Physiother. Res. Int. 2004, 9, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivey, J. The value of qualitative research methods. Pediatr. Nurs. 2012, 38, 319. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V.; Weate, P. Using thematic analysis in sport and exercise research. In International Handbook of Qualitative Methods in Sport and Exercise; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 274–288. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.; Graham, I.D.; Mrklas, K.J.; Bowen, S.; Cargo, M.; Estabrooks, C.A.; Kothari, A.; Lavis, J.; Macaulay, A.C.; MacLeod, M.; et al. How does integrated knowledge translation (iKT) compare to other collaborative research approaches to generating and translating knowledge? Learning from experts in the field. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2020, 18, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gainforth, H.L.; Hoekstra, F.; McKay, R.; McBride, C.B.; Sweet, S.N.; Ginis, K.A.M.; Anderson, K.; Chernesky, J.; Clarke, T.; Forwell, S.; et al. Integrated knowledge translation guiding principles for conducting and disseminating spinal cord injury research in partnership. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2020, 102, 656–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelletier, C.A.; Ward, K.; Pousette, A.; Fox, G. Meaning and experiences of physical activity in rural and northern communities. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2021, 13, 690–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelletier, C.A.; Pousette, A.; Ward, K.; Fox, G. Exploring the perspectives of community members as research partners in rural and remote areas. Res. Involv. Engagem. 2020, 6, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brofenbrenner, U. Ecological Systems Theory; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Golden, S.D.; McLeroy, K.R.; Green, L.W.; Earp, J.A.L.; Lieberman, L.D. Upending the social ecological model to guide health promotion efforts toward policy and environmental change. Health Educ Behav. 2015, 42 (Suppl. 1), 8S–14S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northern Health. Northern Health Region [map]. Available online: https://www.northernhealth.ca/sites/northern_health/files/about-us/quick-facts/documents/nh-map.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Blewett, J.; Hanlon, N. Disablement as inveterate condition: Living with habitual ableism in Prince George, British Columbia. Can. Geogr. 2016, 60, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palinkas, L.A.; Horwitz, S.M.; Green, C.A.; Wisdom, J.P.; Duan, N.; Hoagwood, K. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Adm. Policy Ment. Health 2015, 42, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. What can “thematic analysis” offer health and wellbeing researchers? Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2014, 16, 26152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2019, 11, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowell, L.S.; Norris, J.M.; White, D.E.; Moules, N.J. Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2017, 16, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.; McGannon, K.R. Developing rigor in qualitative research: Problems and opportunities within sport and exercise psychology. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2018, 11, 101–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foulger, T.S. External conversations: An unexpected discovery about the critical friend in action research inquiries. Action Res. 2010, 8, 135–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calder, A.; Sole, G.; Mulligan, H. The accessibility of fitness centers for people with disabilities: A systematic review. Disabil. Health J. 2018, 11, 525–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noe, B.B.; Hoejgaard, A.; Skovbjerg, F.; Steensgaard, R.; Noe, E.B. Rural-urban living with spinal cord injury, impact health, quality of life and integration-Experiences from Denmark. Soc. Sci. Med. 2025, 381, 118300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimino, S.R.; Hitzig, S.L.; Craven, B.C.; Bassett-Gunter, R.L.; Li, J.; Guilcher, S.J.T. An exploration of perceived social isolation among persons with spinal cord injury in Ontario, Canada: A qualitative study. Disabil Rehabil. 2020, 44, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopmans, A.; Pelletier, C. Physical activity experiences of people with multiple sclerosis during the COVID-19 pandemic. Disabilities 2022, 2, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakespeare, T.; Ndagire, F.; Seketi, Q.E. Triple jeopardy: Disabled people and the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 2021, 397, 1331–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Participants (n = 12) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | <30 | 1 (8%) |

| 30–39 | 2 (17%) | |

| 40–49 | 4 (33%) | |

| 50–59 | 3 (25%) | |

| 60–69 | 2 (17%) | |

| Gender | Woman | 6 (50%) |

| Man | 6 (50%) | |

| Community population | <5000 | 1 (8%) |

| 10,000–25,000 | 5 (42%) | |

| 50,000–100,000 | 6 (50%) | |

| Disability | Cerebral Palsy | 3 (25%) |

| Spinal Cord Injury | 3 (25%) | |

| Amputation | 2 (17%) | |

| Multiple Sclerosis | 1 (8%) | |

| Muscular dystrophy | 1 (8%) | |

| Spina Bifida | 1 (8%) | |

| Other | 1 (8%) | |

| Time with disability (years) | <10 | 2 (17%) |

| 10–19 | 1 (8%) | |

| 20–29 | 3 (25%) | |

| 30–39 | 3 (25%) | |

| >40 | 3 (25%) | |

| Mobility aid | Power chair | 7 (58%) |

| Manual wheelchair | 9 (75%) | |

| Scooter | 1 (8%) | |

| Walker | 2 (17%) | |

| Crutches | 1 (8%) | |

| Prosthetic or orthotic | 2 (17%) |

| Theme | Subtheme | Example Codes |

|---|---|---|

| Physical accessibility of spaces and places | Facilities and indoor spaces | • Access to enter buildings |

| • Stairs within buildings | ||

| • Washrooms not accessible | ||

| Outdoor spaces | • Inaccessible parking | |

| • Winter weather | ||

| • Not universally accessible | ||

| Availability of resources | • Lack of appropriate equipment | |

| • Cost to individual or businesses/facilities | ||

| • Individual energy and motivation limited (e.g., fatigue) | ||

| Advocates are needed to share knowledge | Representation in organizations and programs | • Increase representation of people with disabilities in organizations as decision makers or program providers |

| • Lack of organized programs for people with disability | ||

| Education and awareness | • Businesses/facilities need education to improve accessibility | |

| • Sharing information with other people with disabilities | ||

| • Education can improve attitudes | ||

| Changing attitudes | • Fear of judgement/embarrassment | |

| • Individual attitudes about physical abilities | ||

| • Advocates can be important | ||

| • Positive attitude fosters inclusion | ||

| Social inclusion and social/physical activities influence each other | Social inclusion facilitates social/physical activity | • More social inclusion/participation leads to more programming |

| • Peers share knowledge of opportunities | ||

| Social/physical activity facilitates social inclusion | • Engaging in physical activity with others fosters feelings of inclusion | |

| • Team sports increase social bonding |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Korolek, K.; Ward, K.; Lamb, H.; McBride, C.B.; Bailey, K.; Pelletier, C. Inclusion as a Facilitator of Social and Physical Activity for People with Physical Disabilities. Disabilities 2025, 5, 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities5030078

Korolek K, Ward K, Lamb H, McBride CB, Bailey K, Pelletier C. Inclusion as a Facilitator of Social and Physical Activity for People with Physical Disabilities. Disabilities. 2025; 5(3):78. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities5030078

Chicago/Turabian StyleKorolek, Kayla, Kirsten Ward, Heather Lamb, Christopher B. McBride, Katherine Bailey, and Chelsea Pelletier. 2025. "Inclusion as a Facilitator of Social and Physical Activity for People with Physical Disabilities" Disabilities 5, no. 3: 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities5030078

APA StyleKorolek, K., Ward, K., Lamb, H., McBride, C. B., Bailey, K., & Pelletier, C. (2025). Inclusion as a Facilitator of Social and Physical Activity for People with Physical Disabilities. Disabilities, 5(3), 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities5030078