Application of Photochemistry in Natural Product Synthesis: A Sustainable Frontier

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Photochemical Reactions with Known/Studied NPS Applications

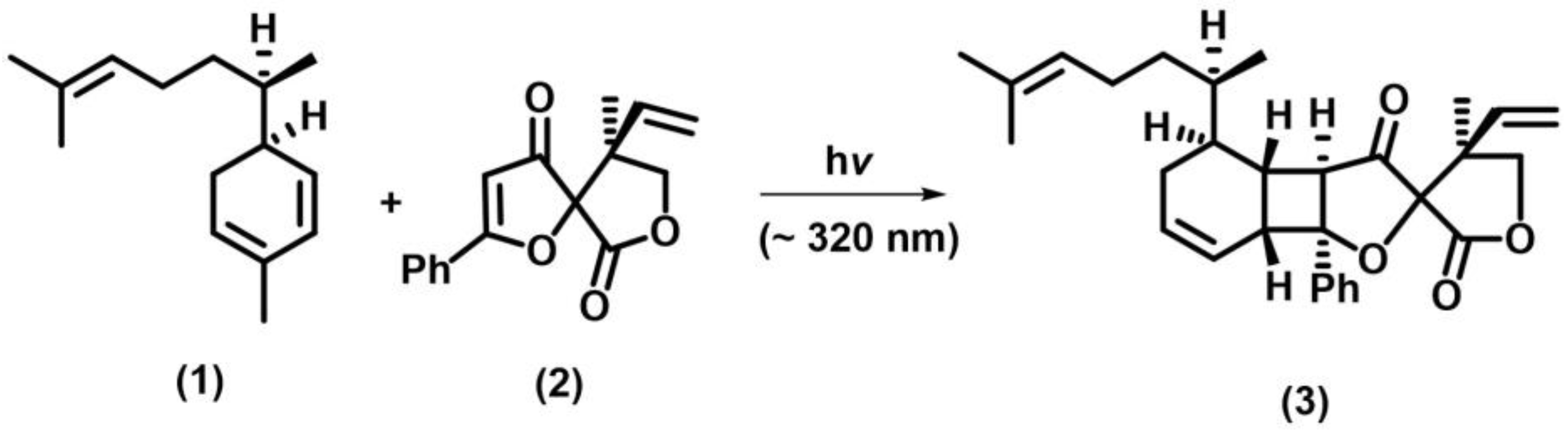

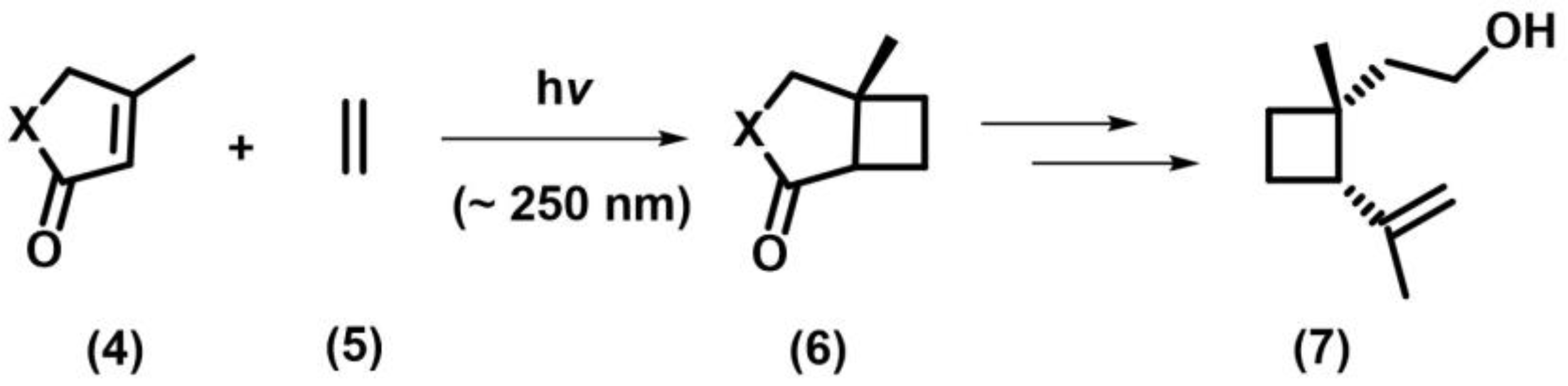

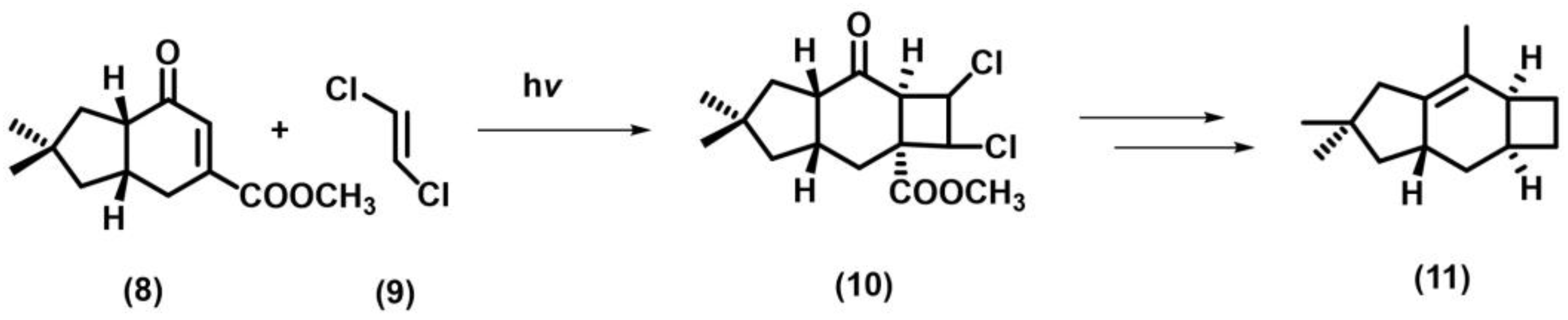

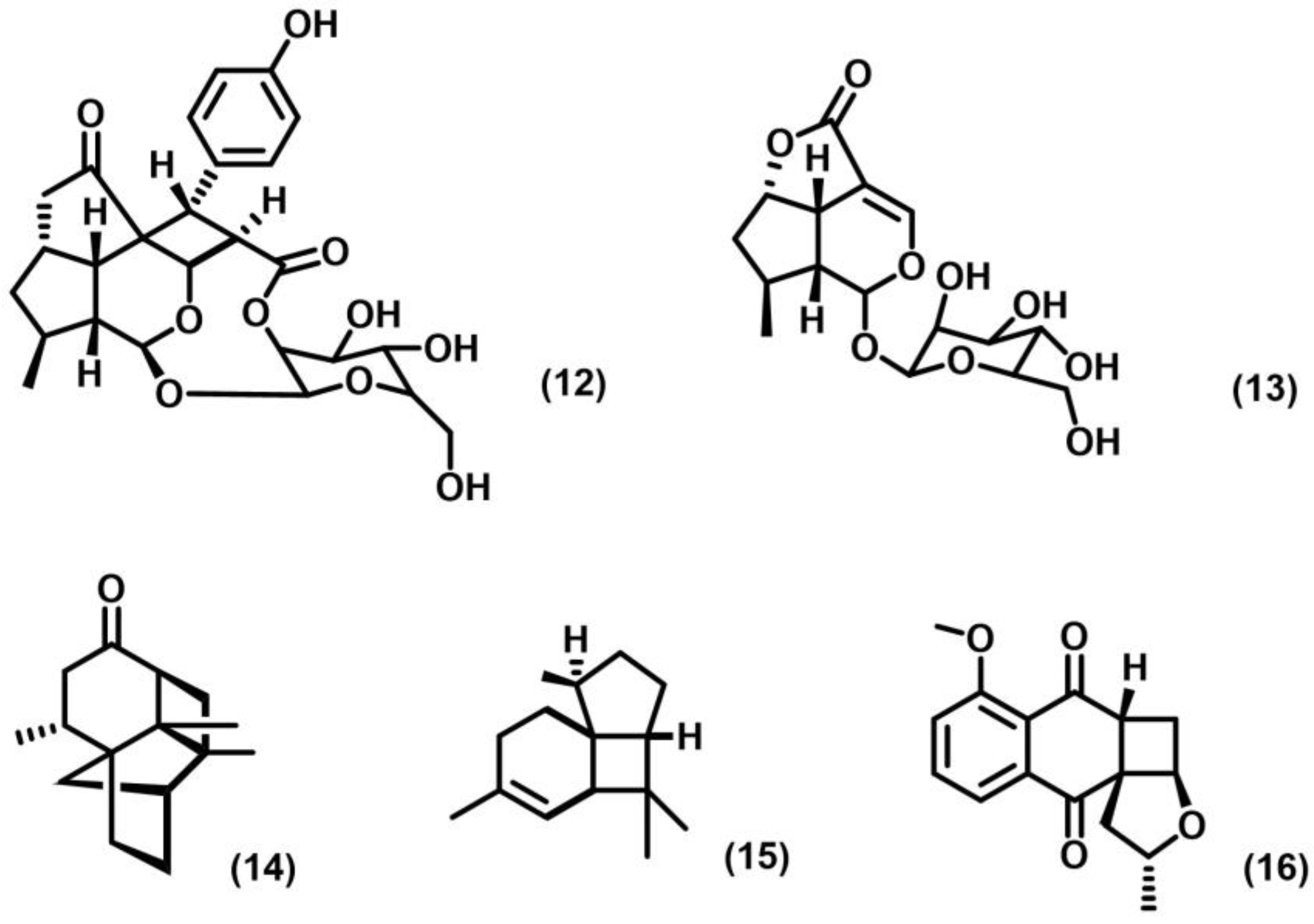

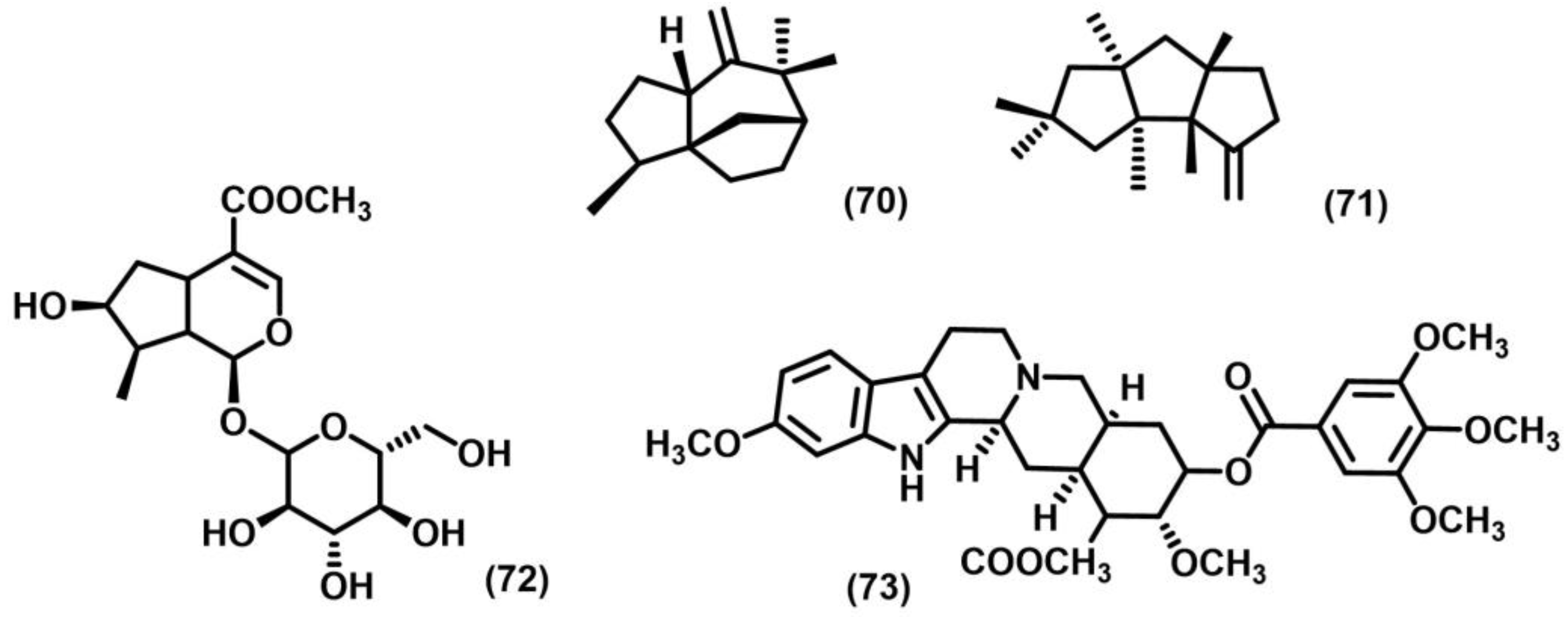

2.1. [2+2] Photocycloaddition of Olefins

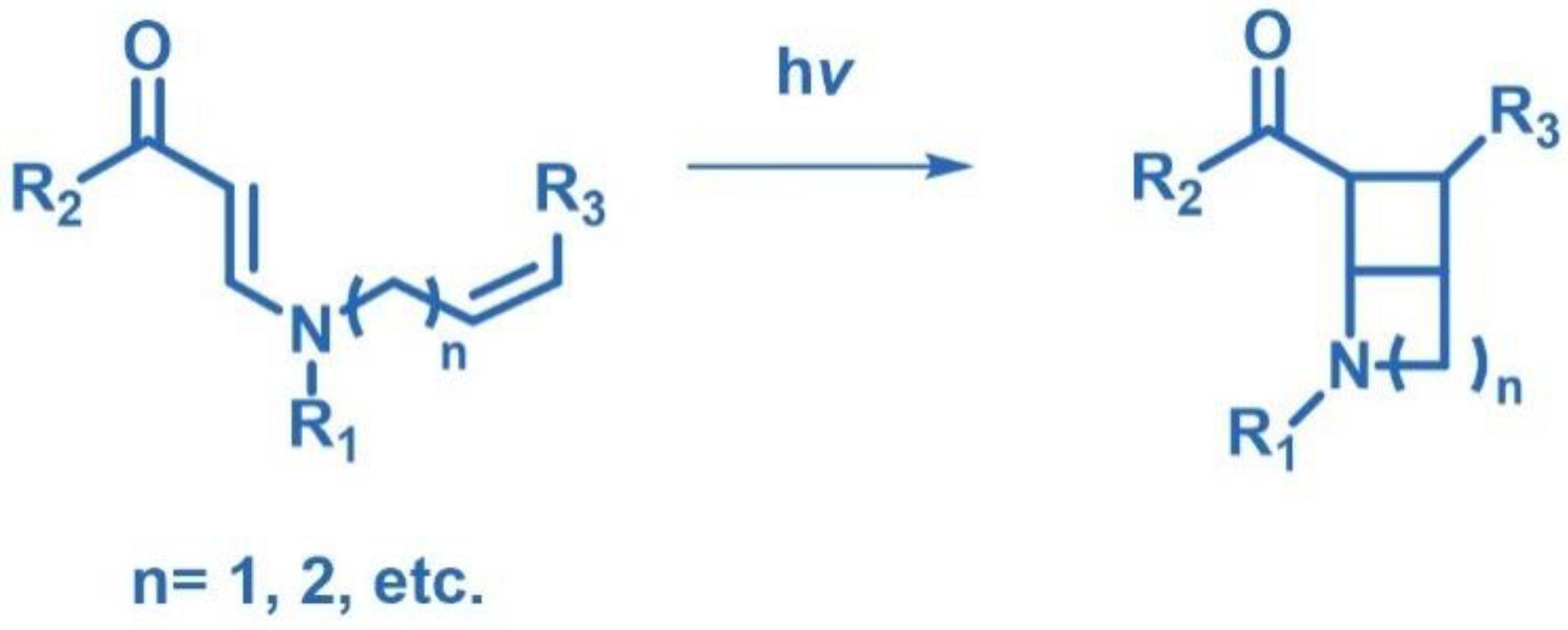

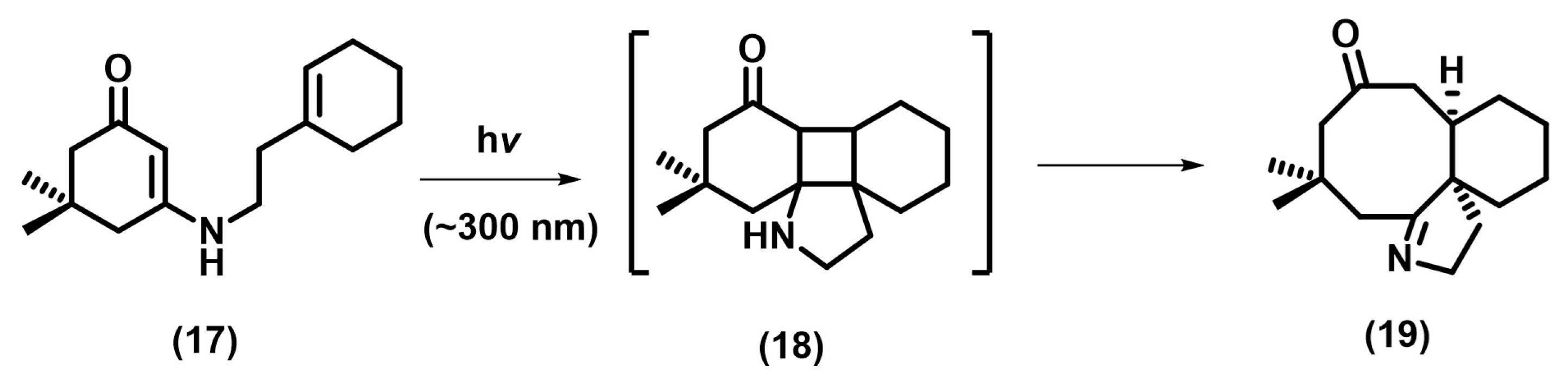

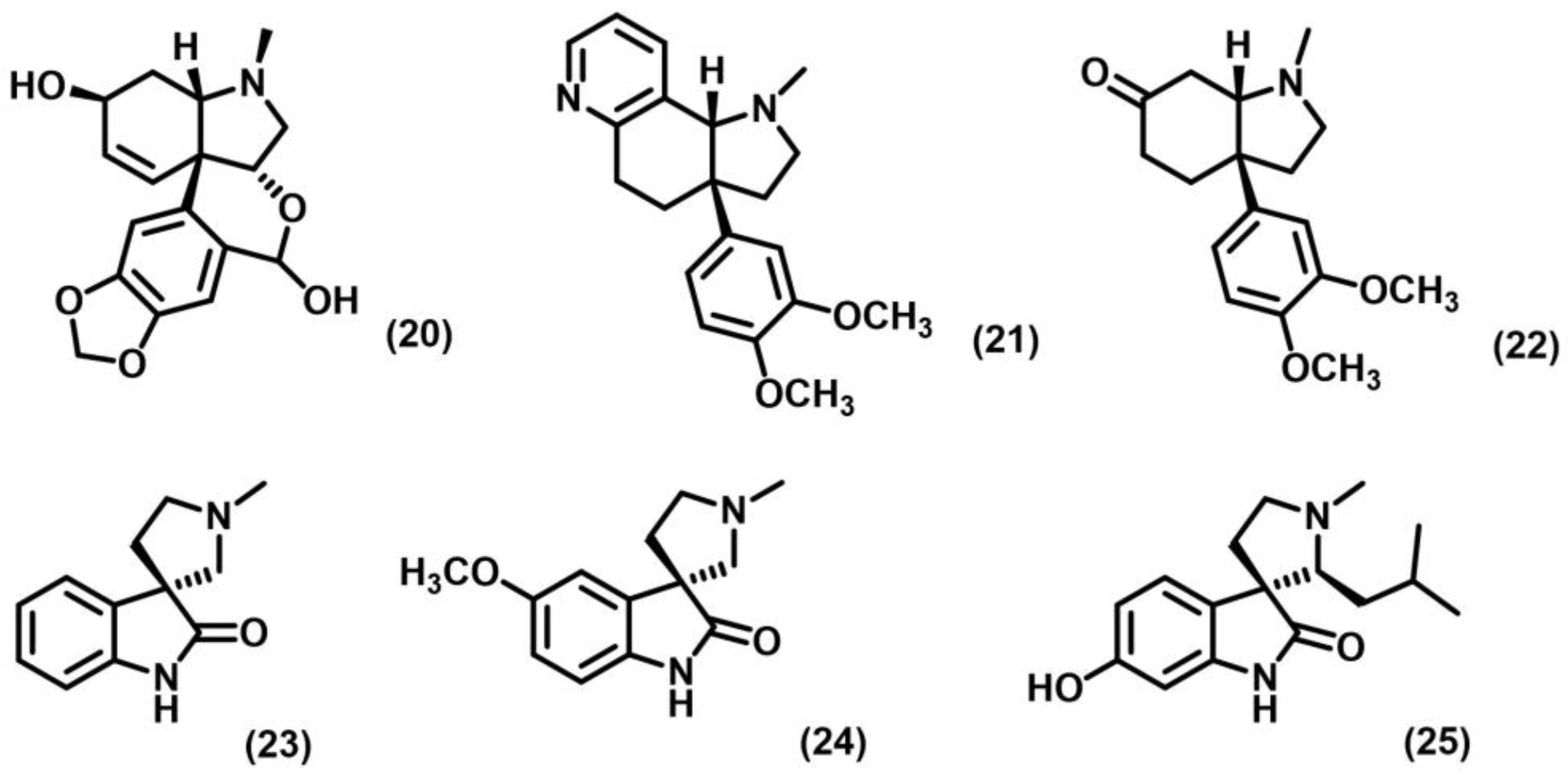

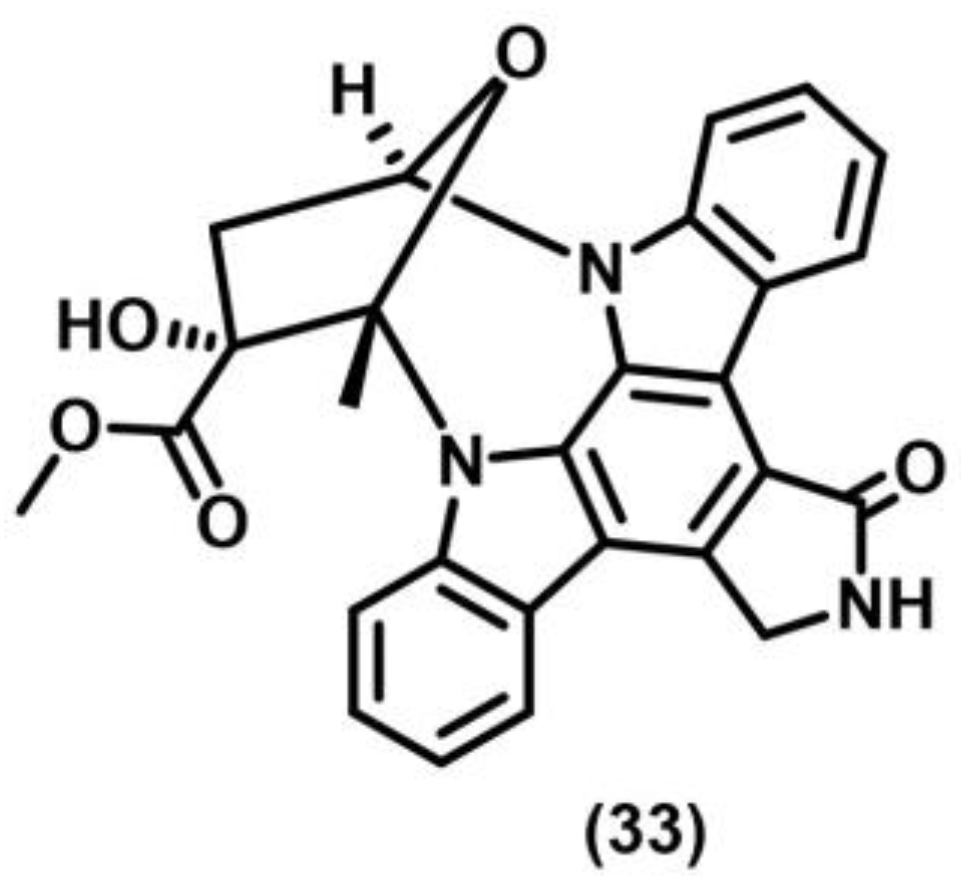

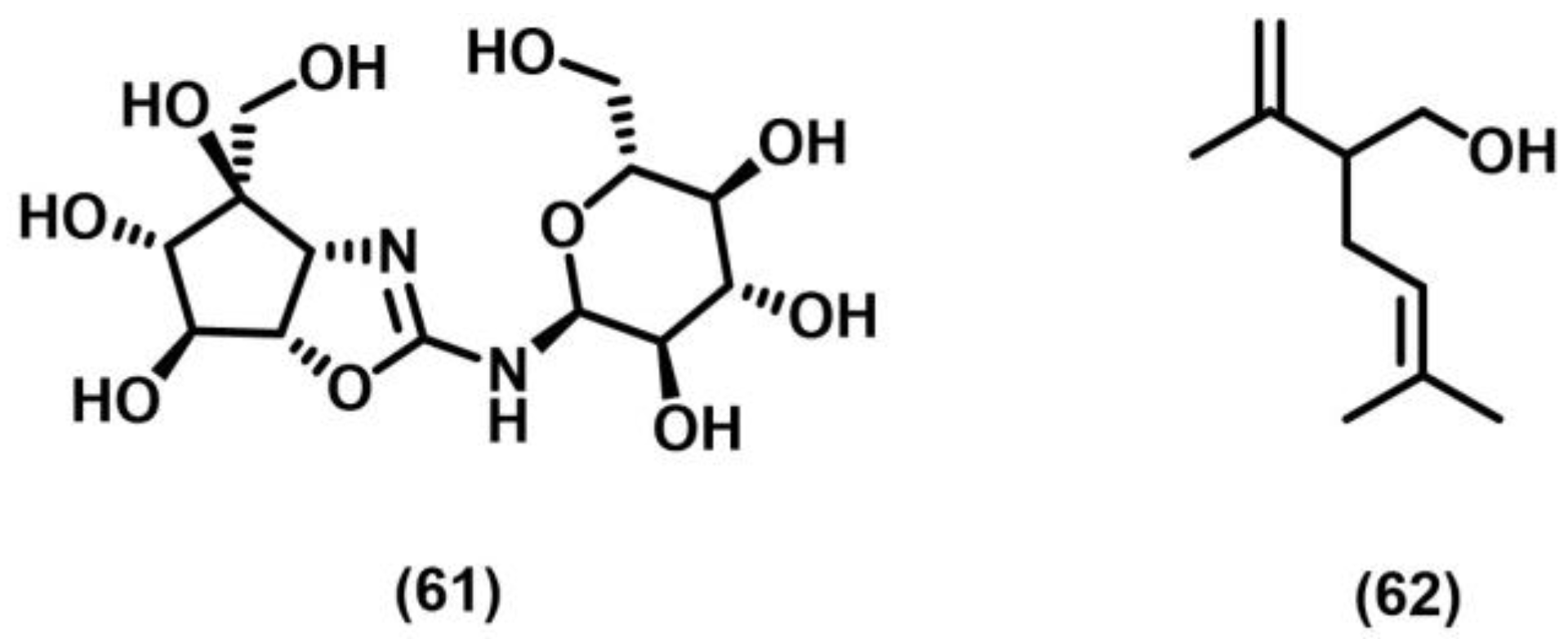

2.2. [2+2] Photocycloaddition of Compounds Containing N

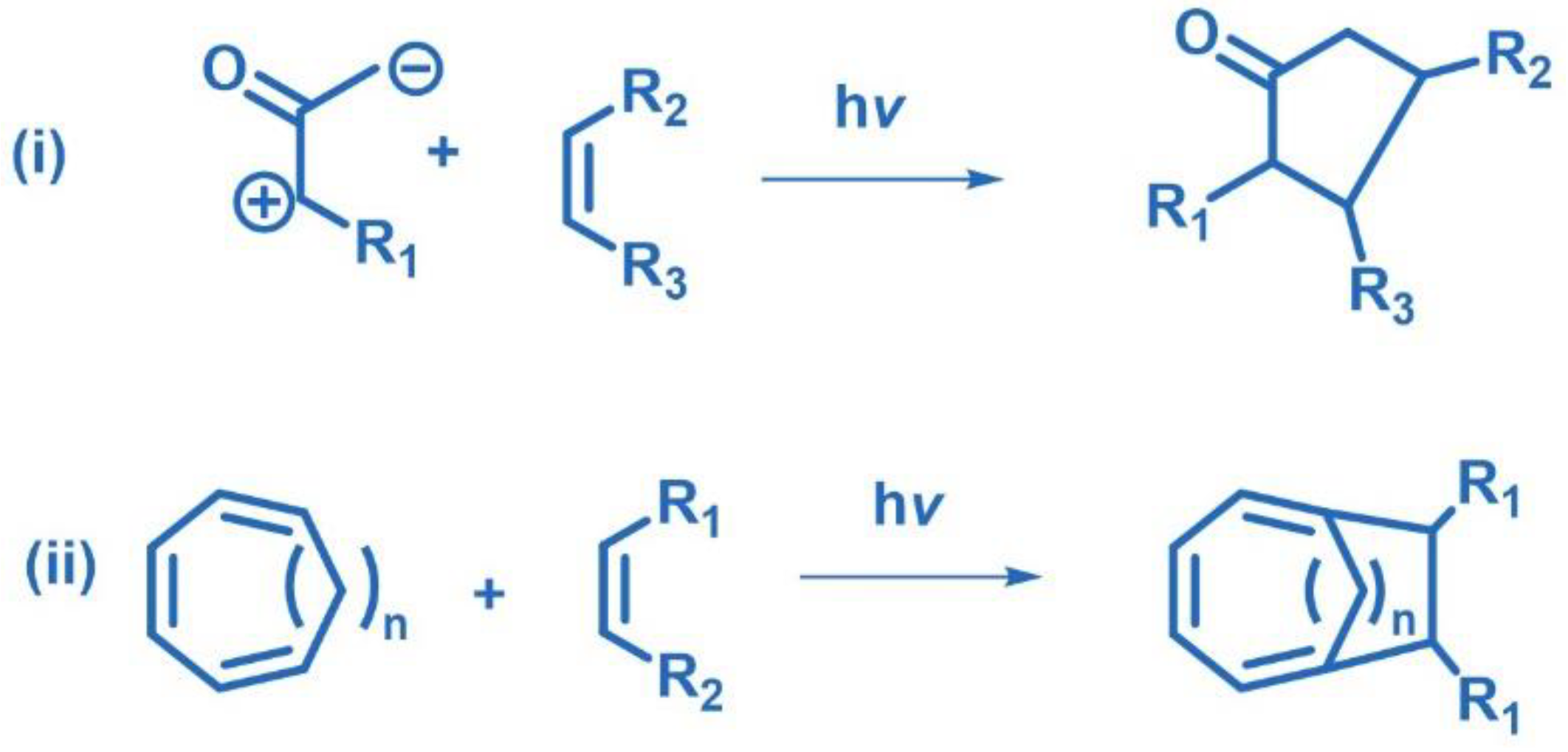

2.3. Other Photocycloadditions ([3+2], [6+2])

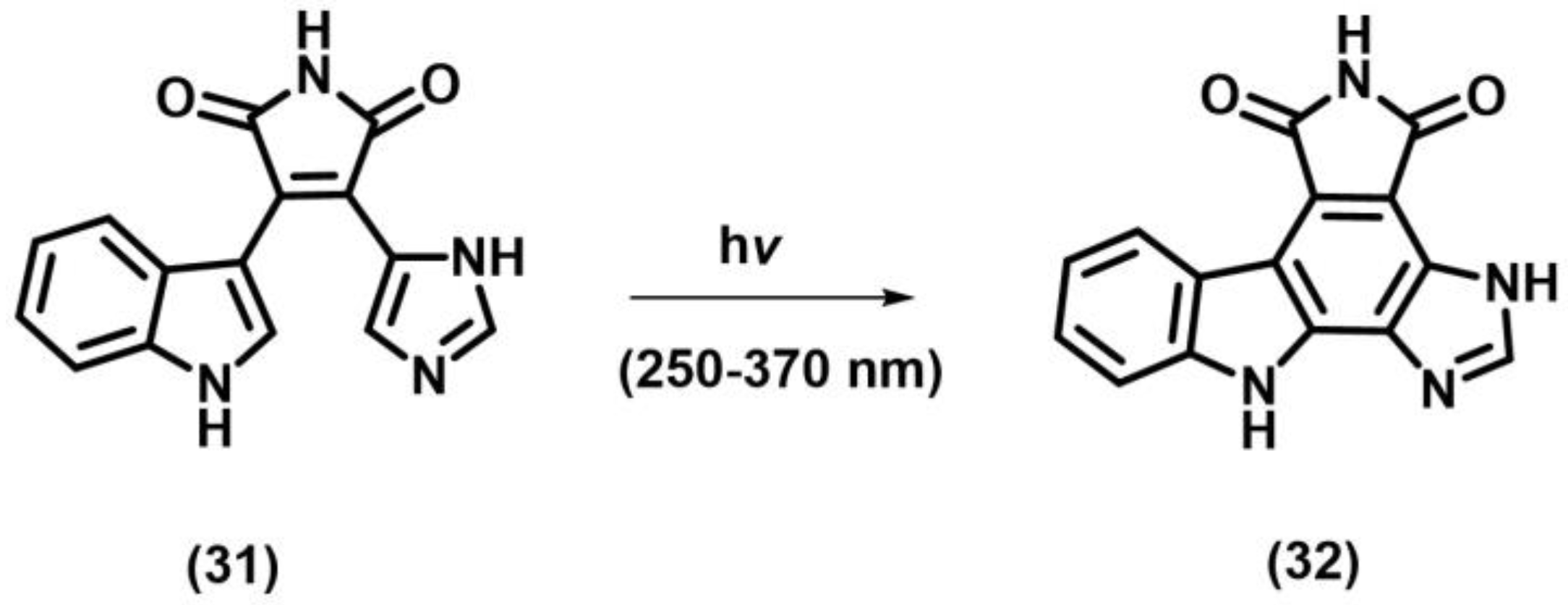

2.4. Photocyclization Reaction

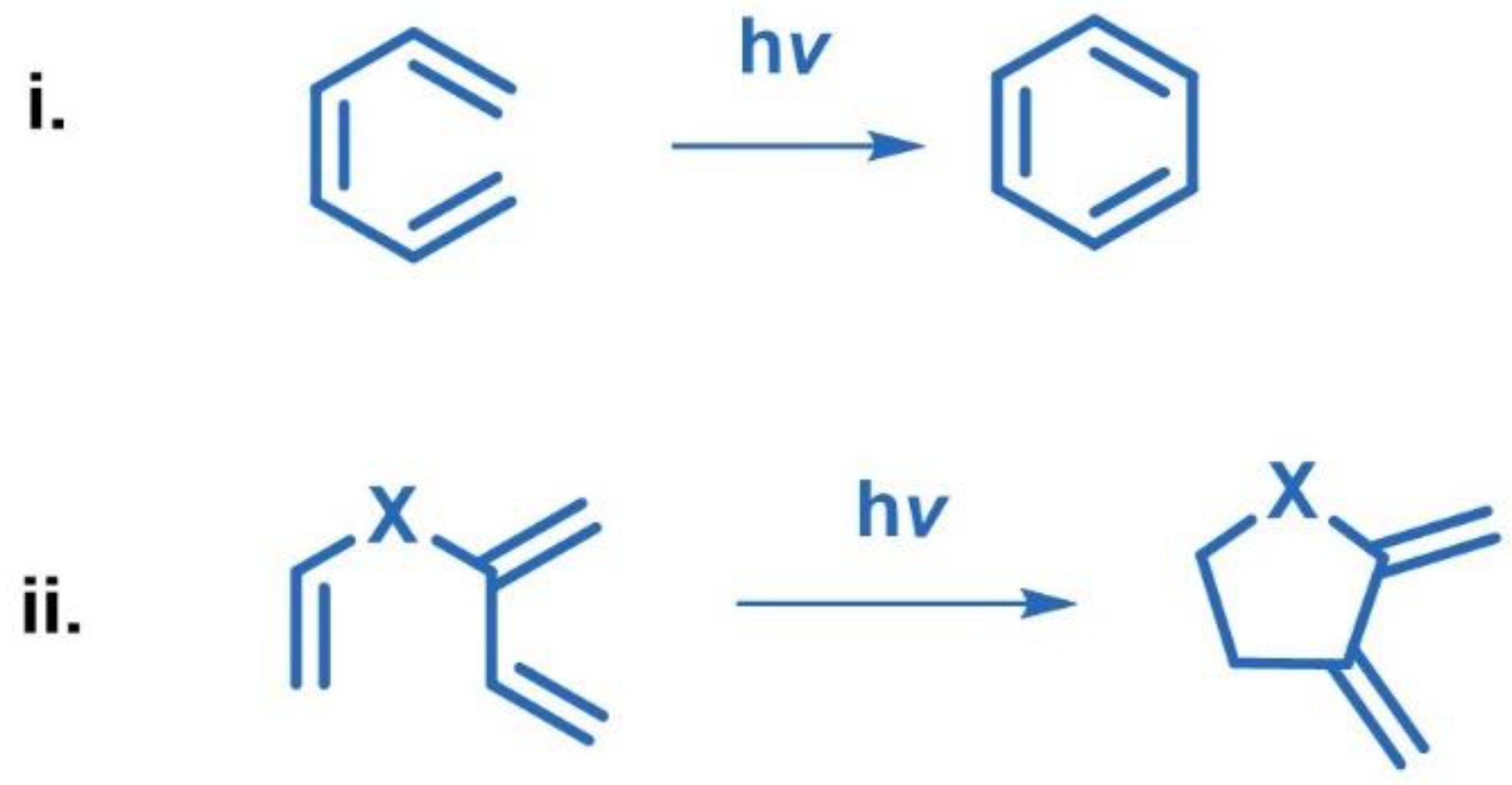

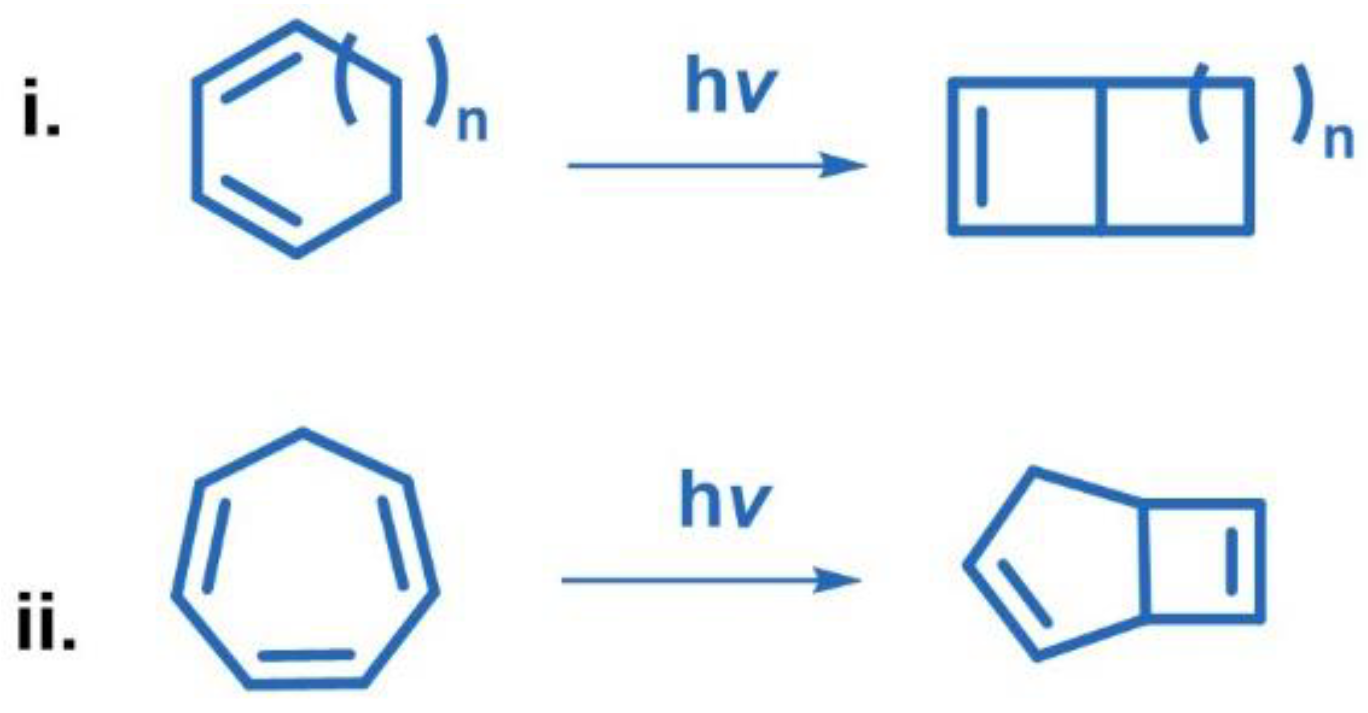

2.4.1. [6π] Photocyclization

2.4.2. [4π] Photocyclization

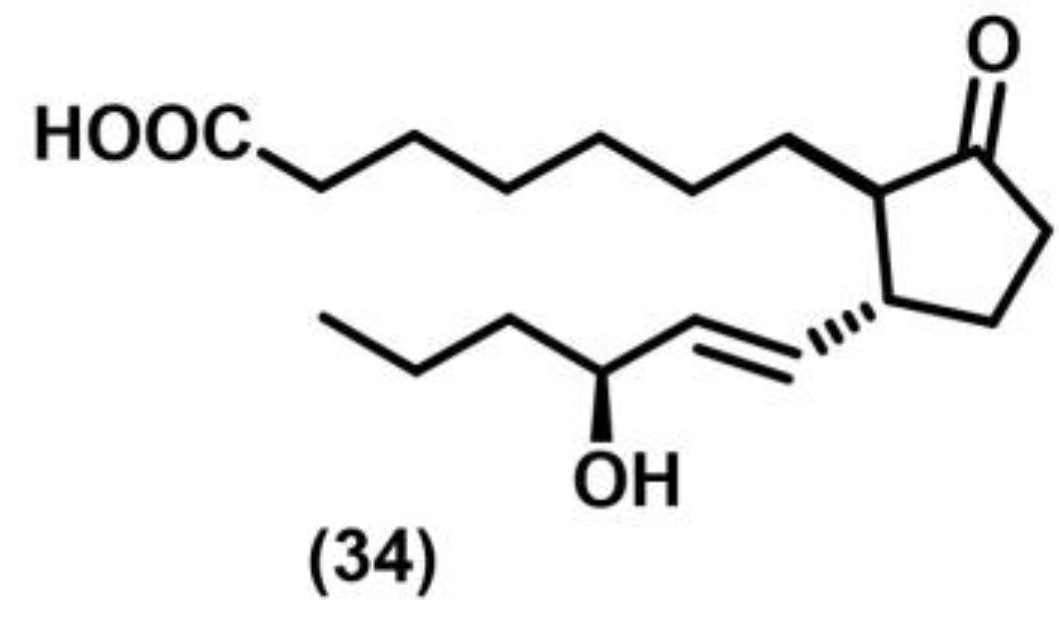

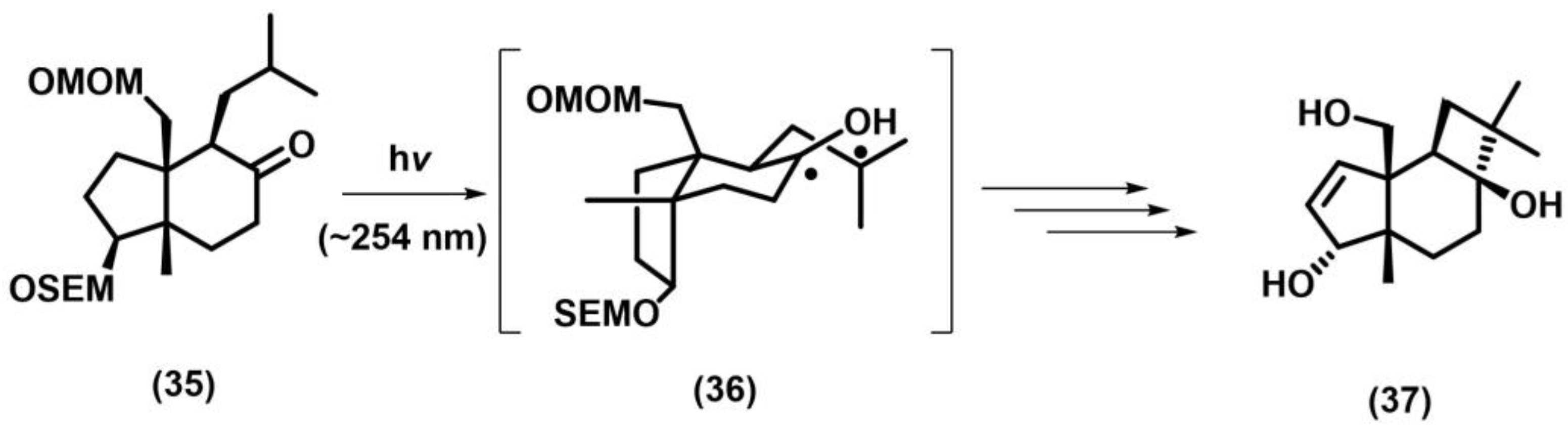

2.5. Norrish–Yang Cyclization

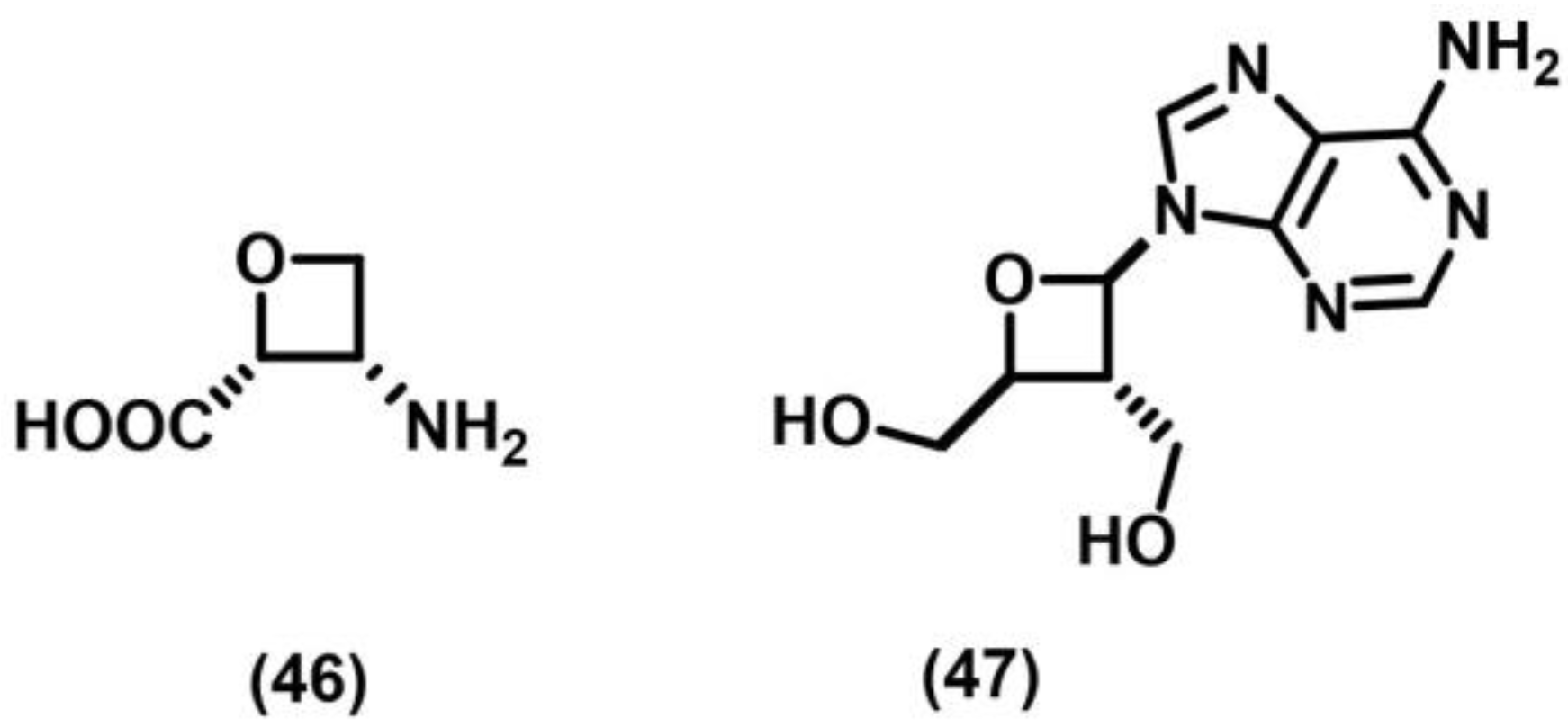

2.6. Paterno–Buchi Photoreaction

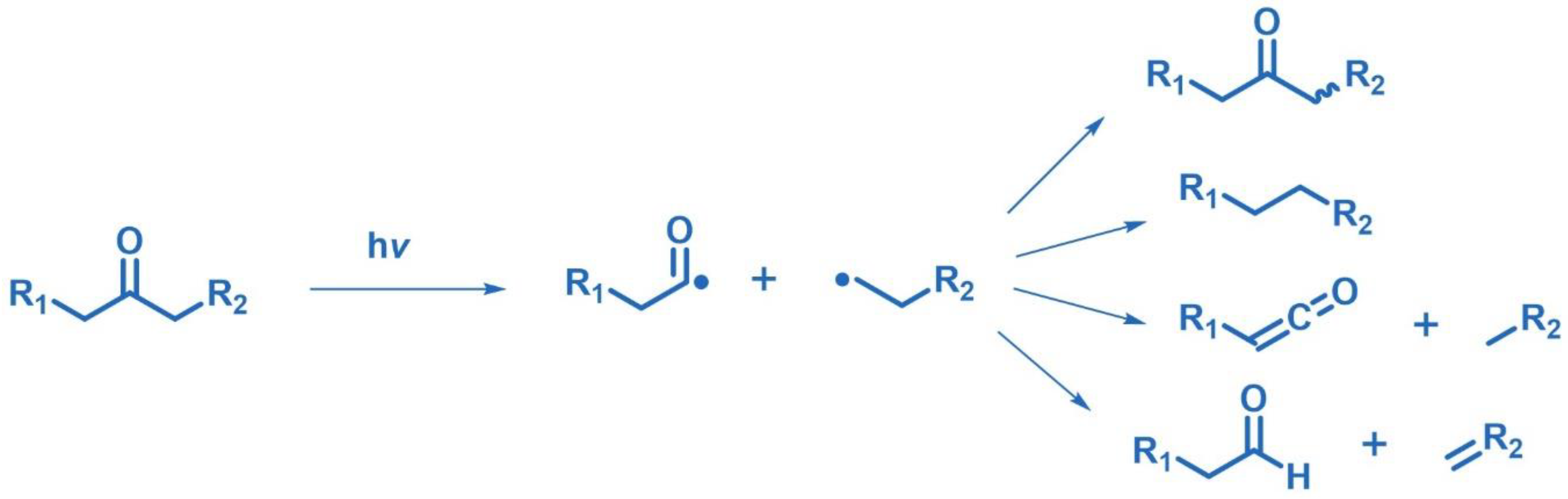

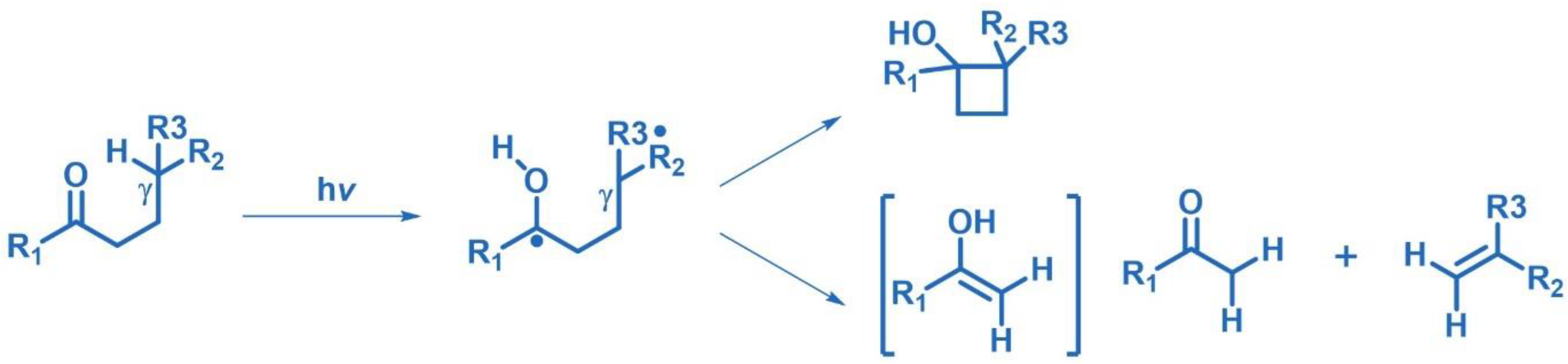

2.7. Norrish Type I/II Photoreactions

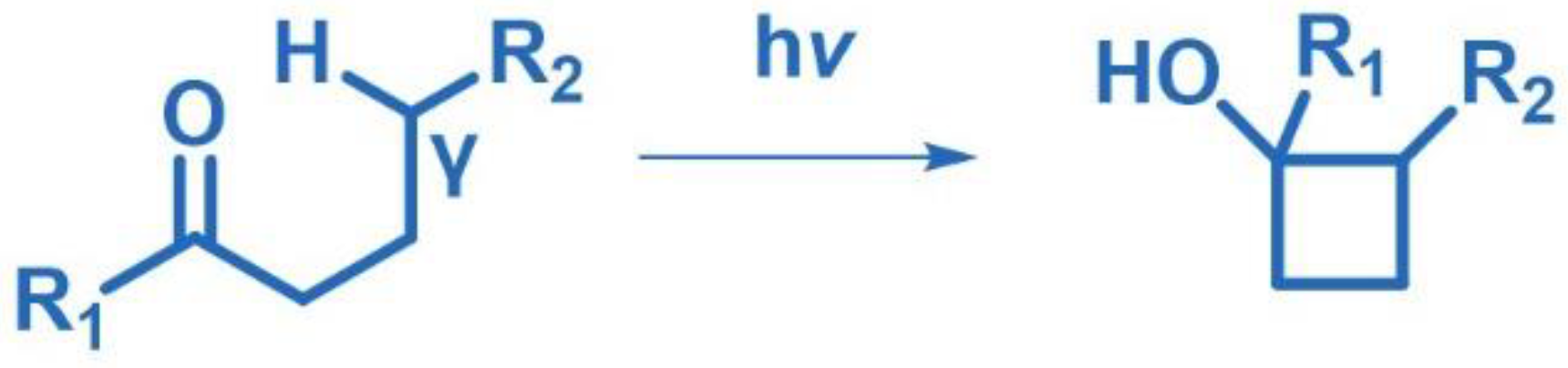

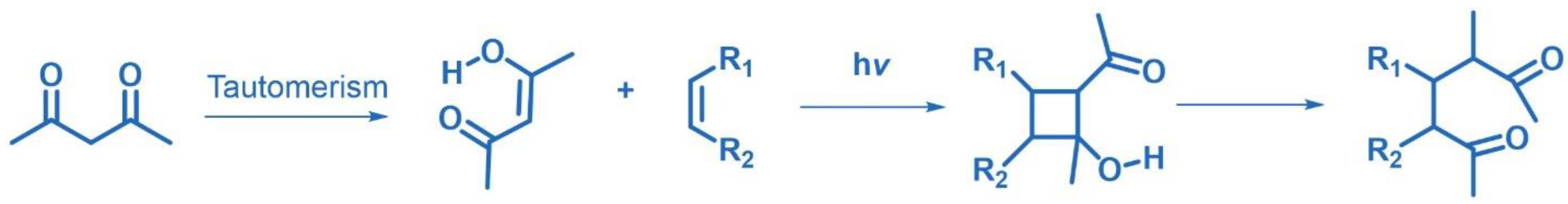

2.8. De-Mayo Photoreaction

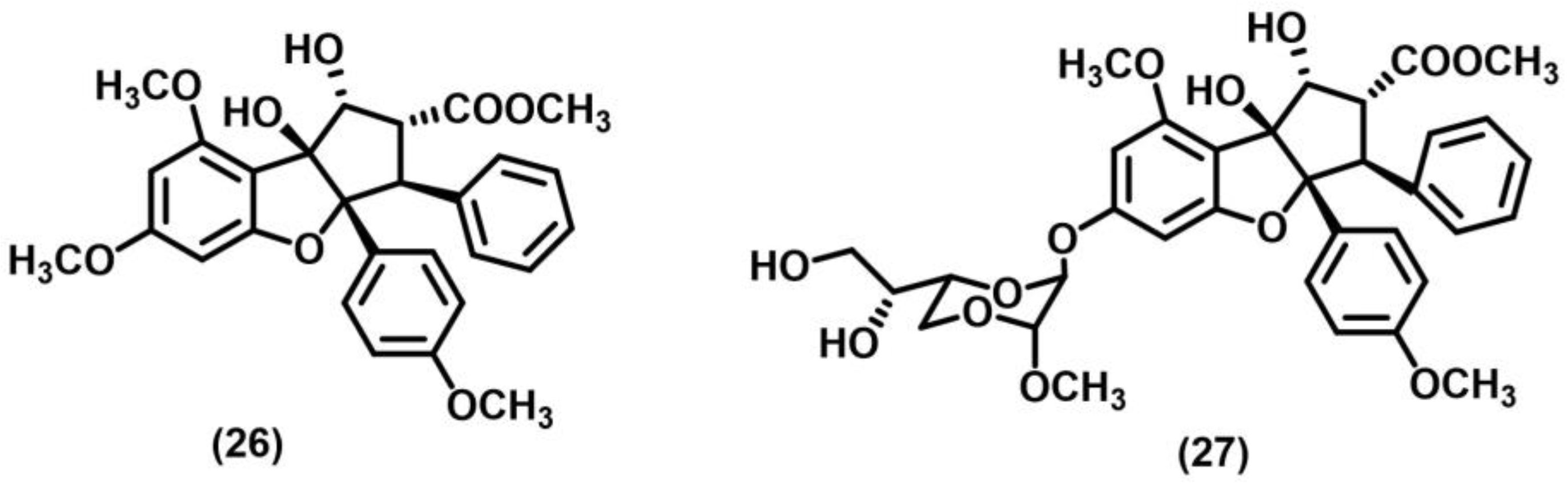

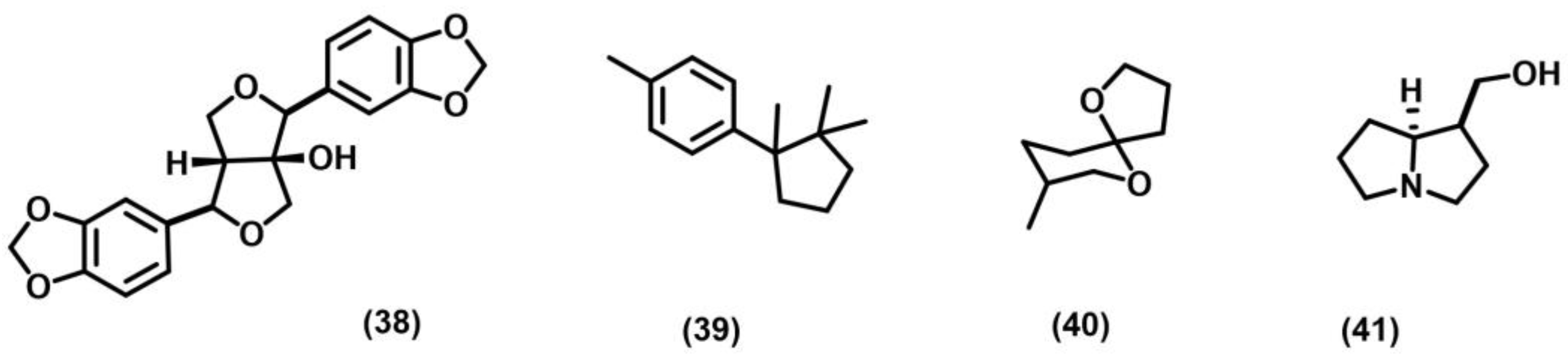

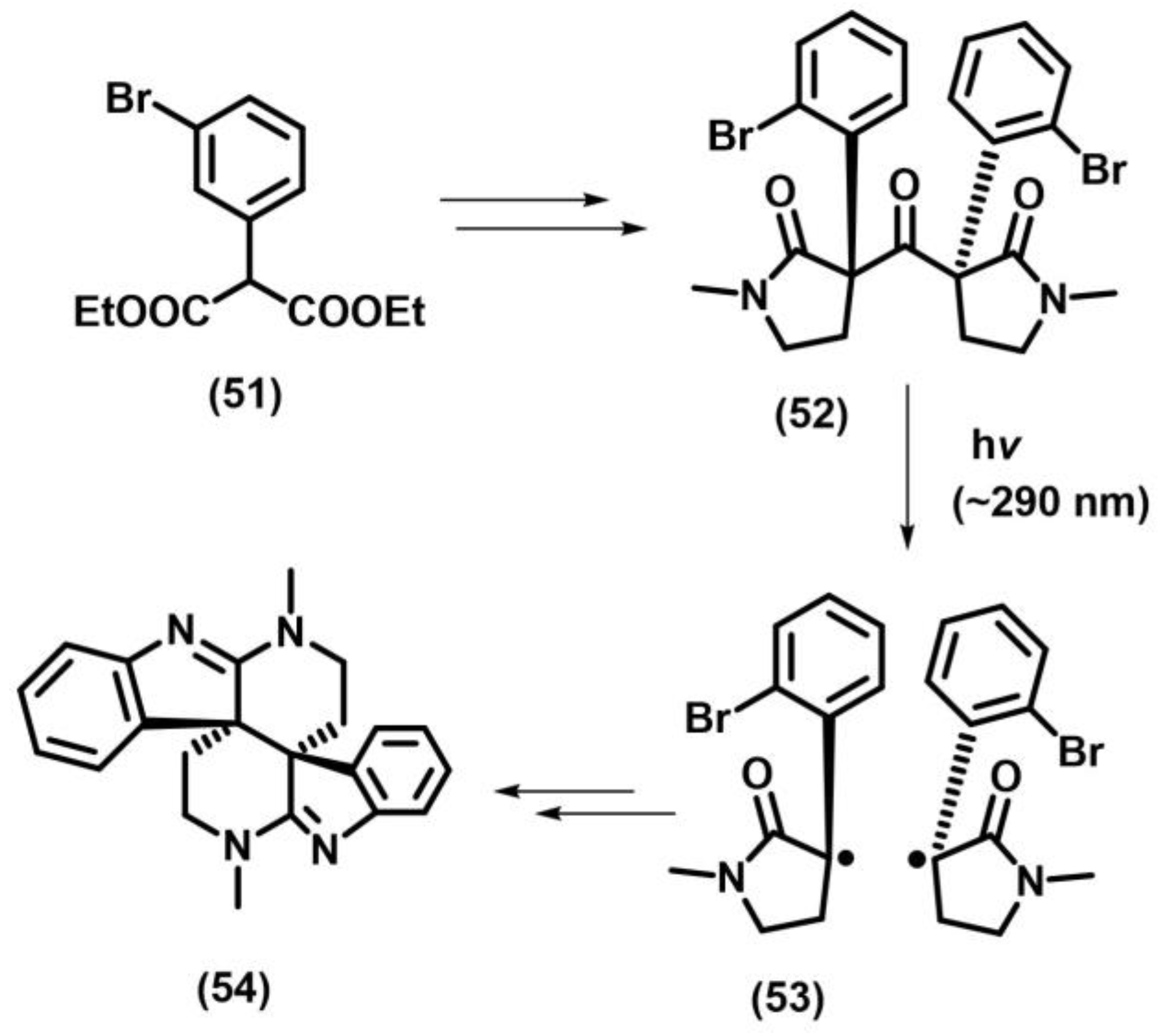

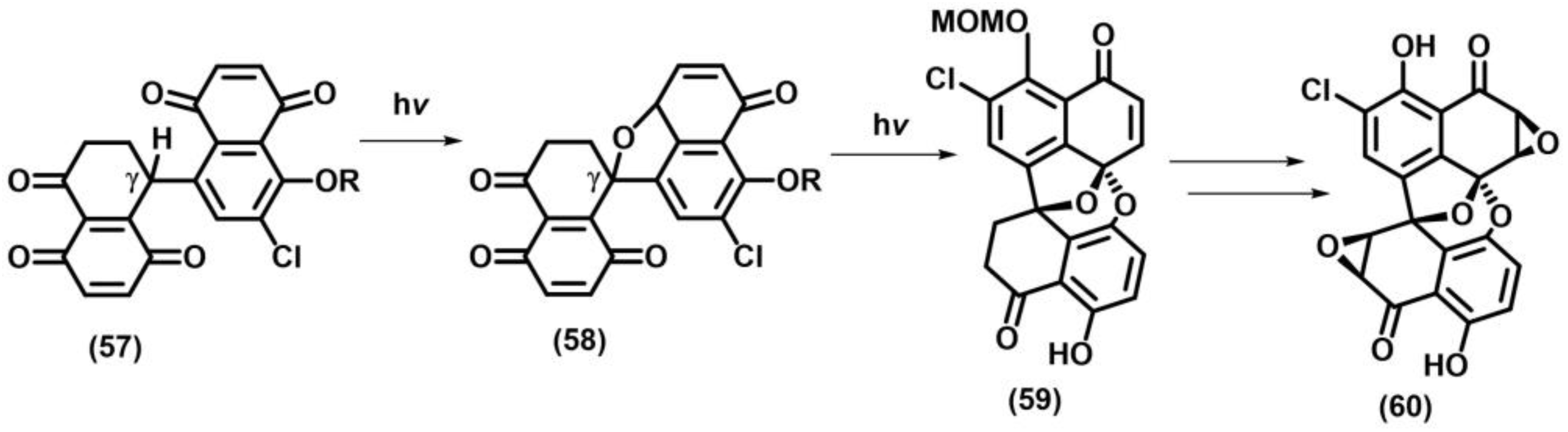

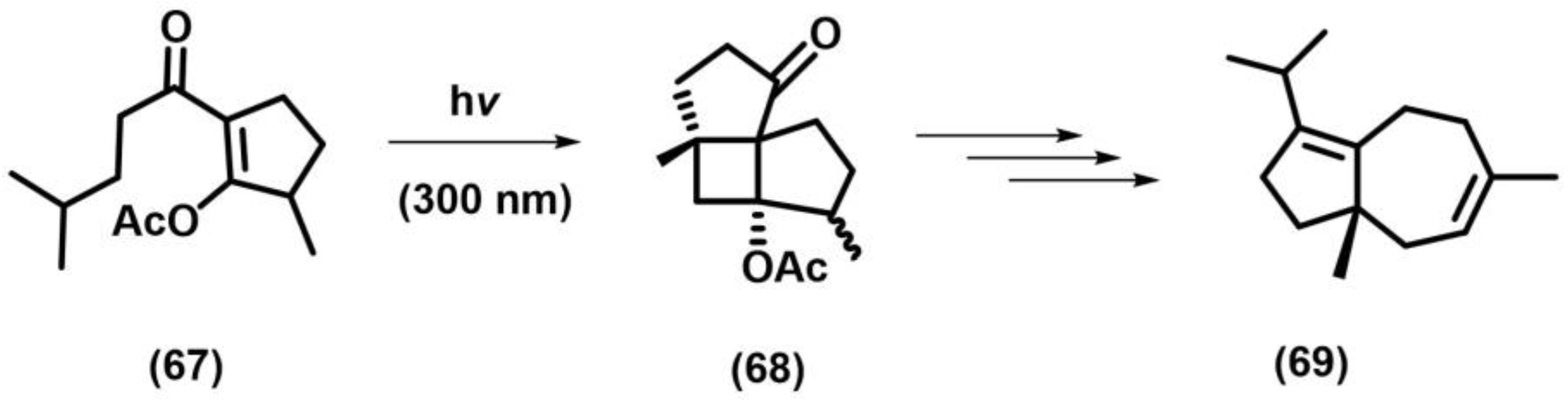

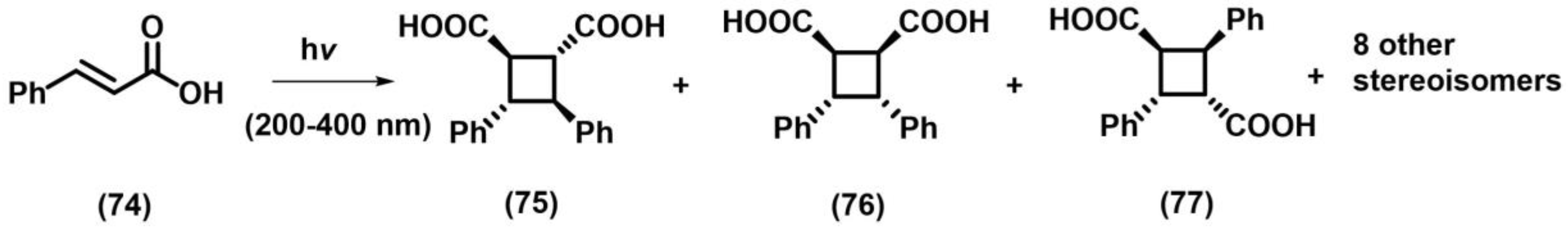

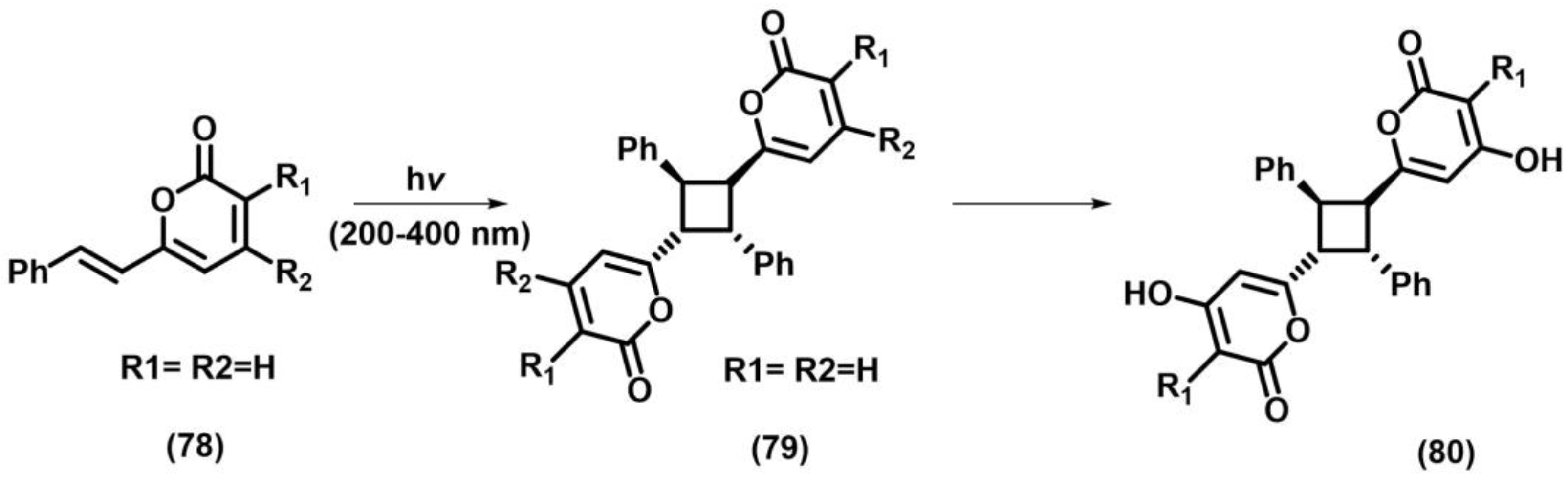

2.9. Homodimerization Photoreaction

2.10. Photochemical Rearrangements

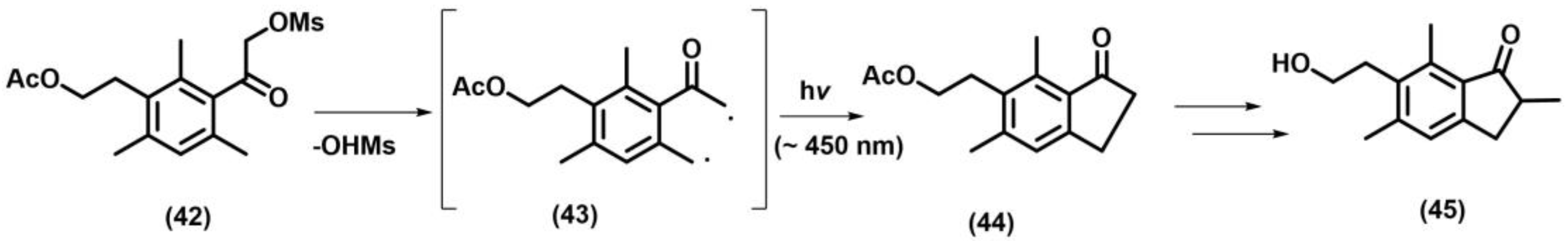

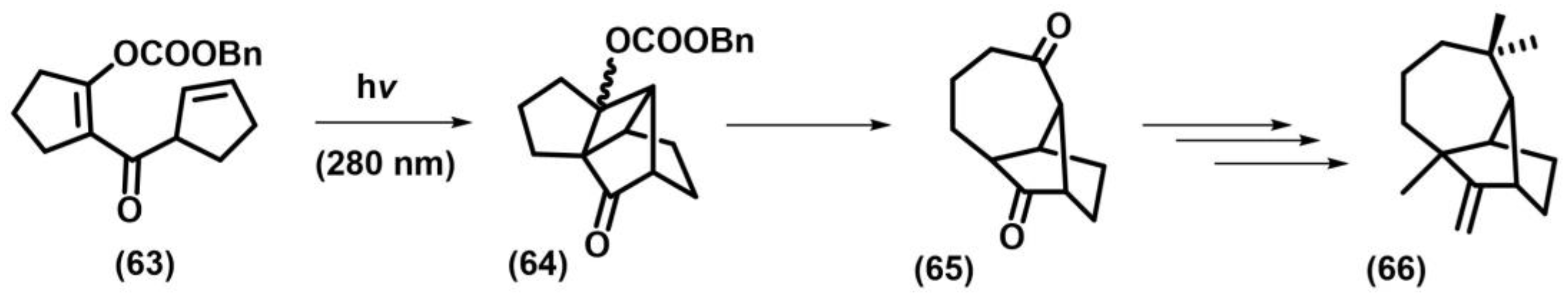

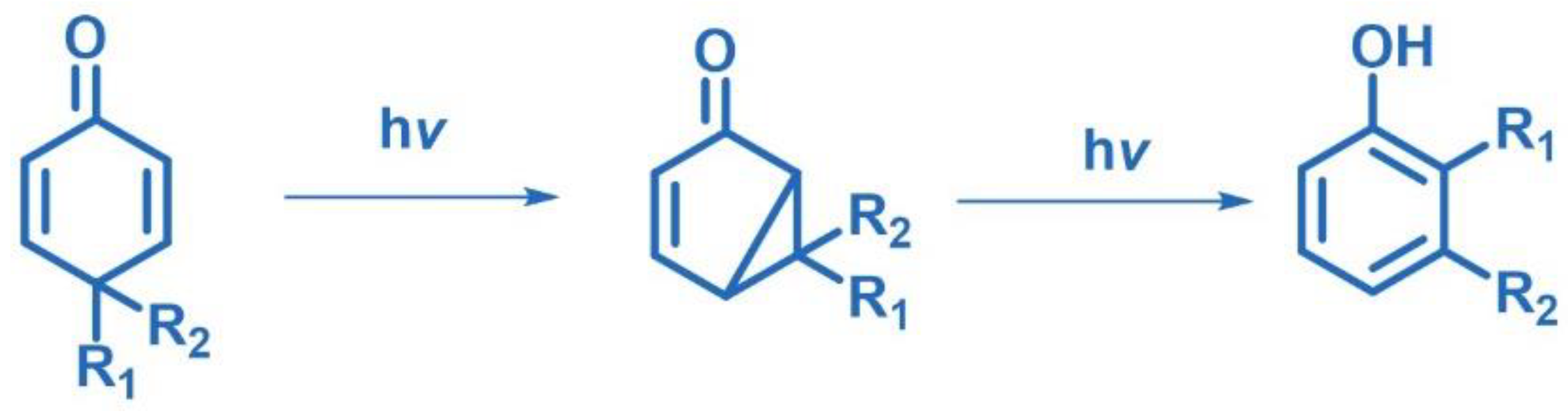

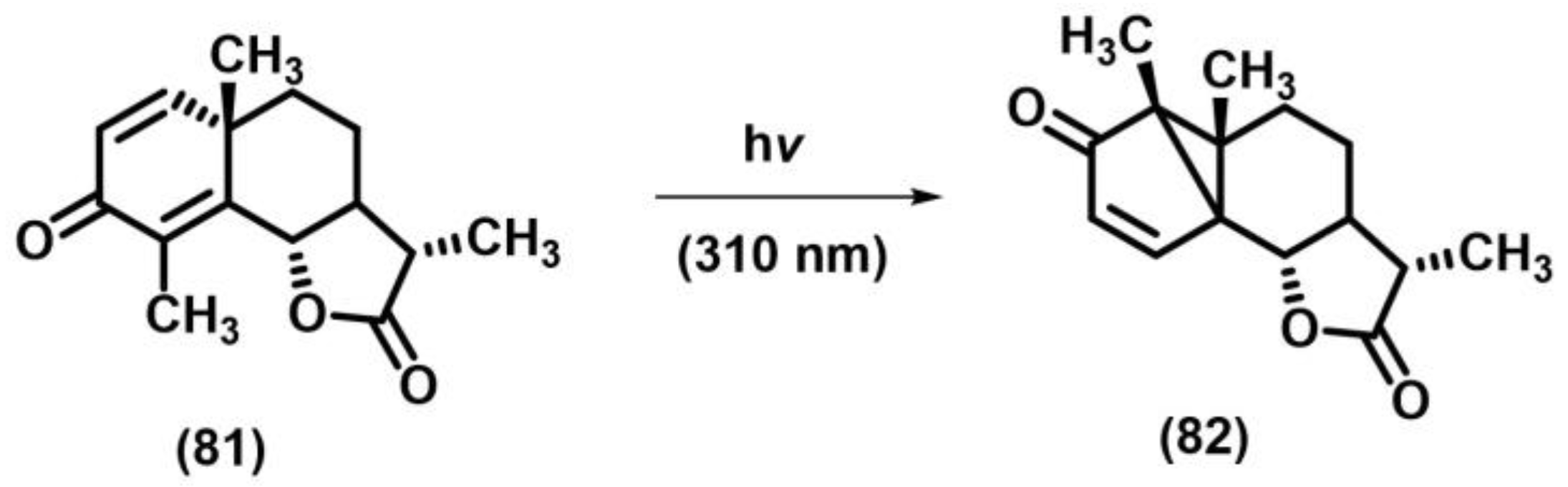

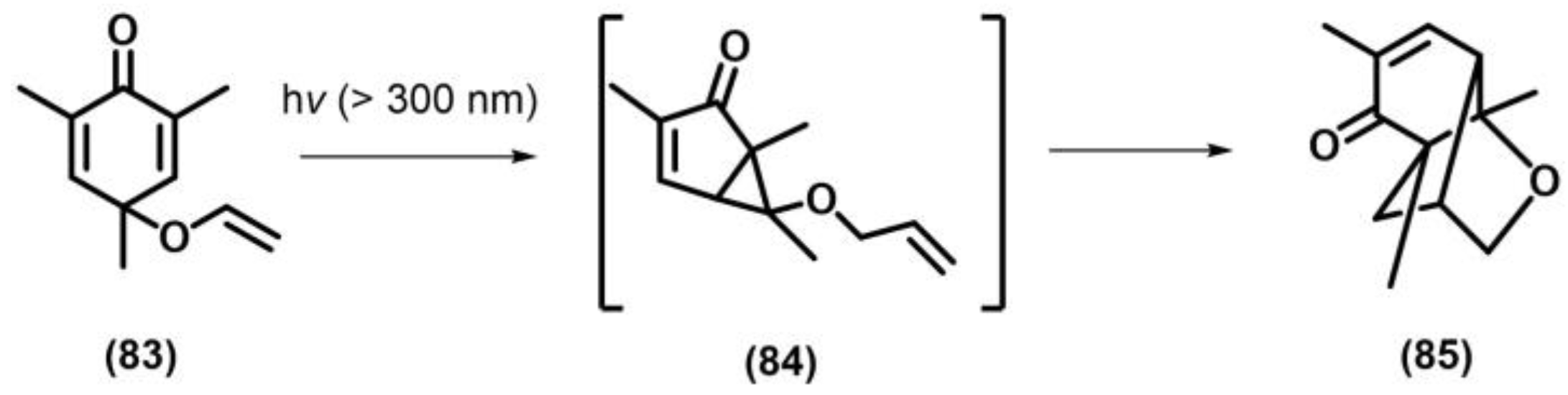

2.10.1. Rearrangement Involving Dienones and Aliphatic Enones

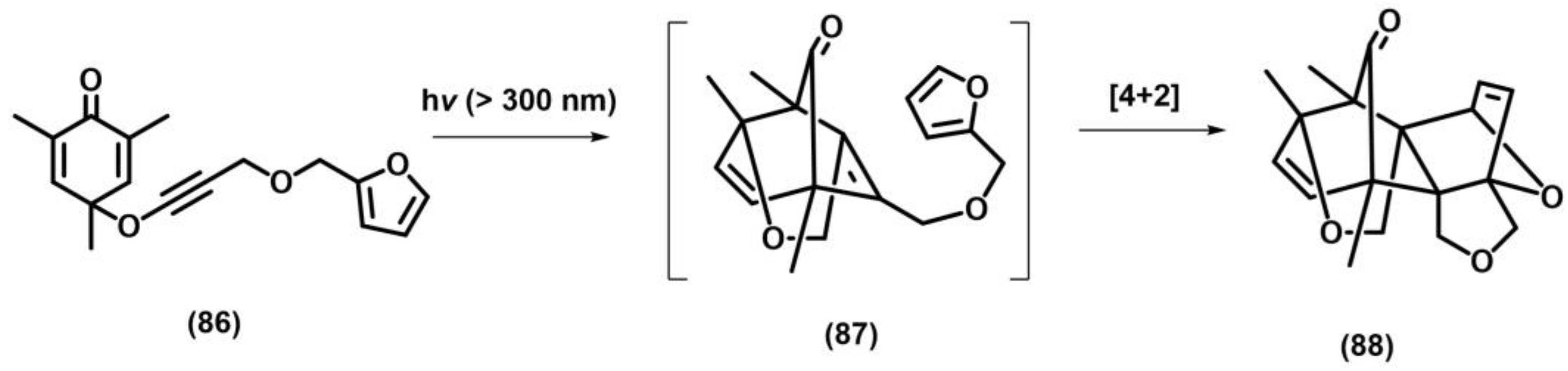

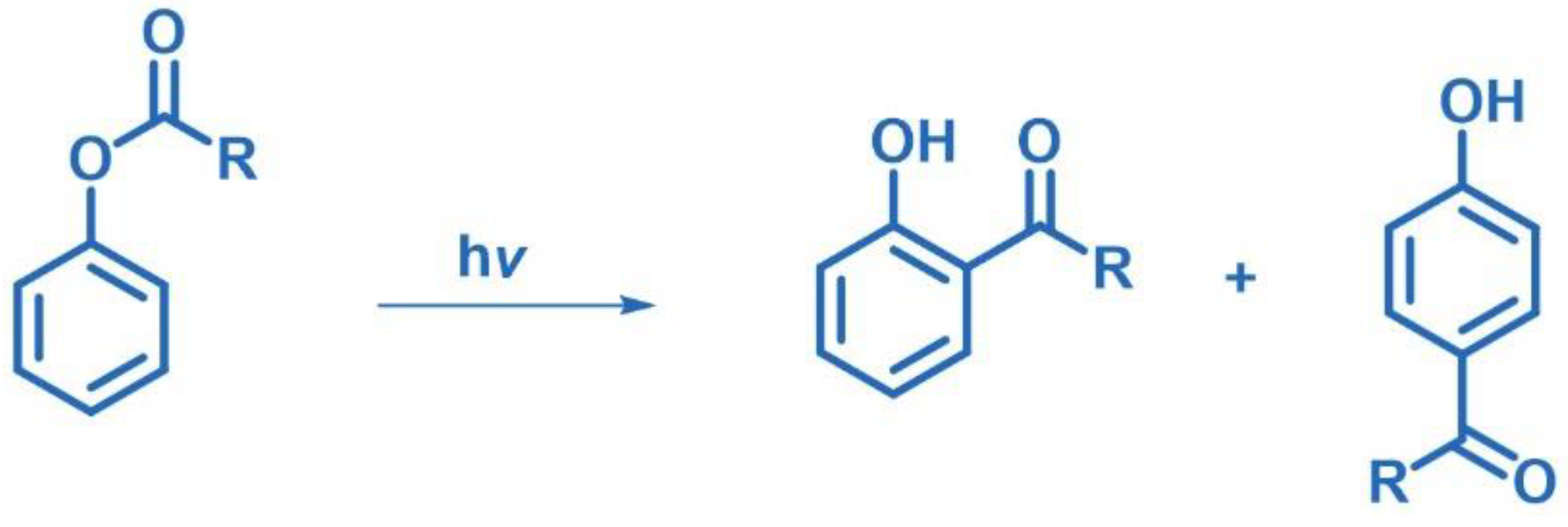

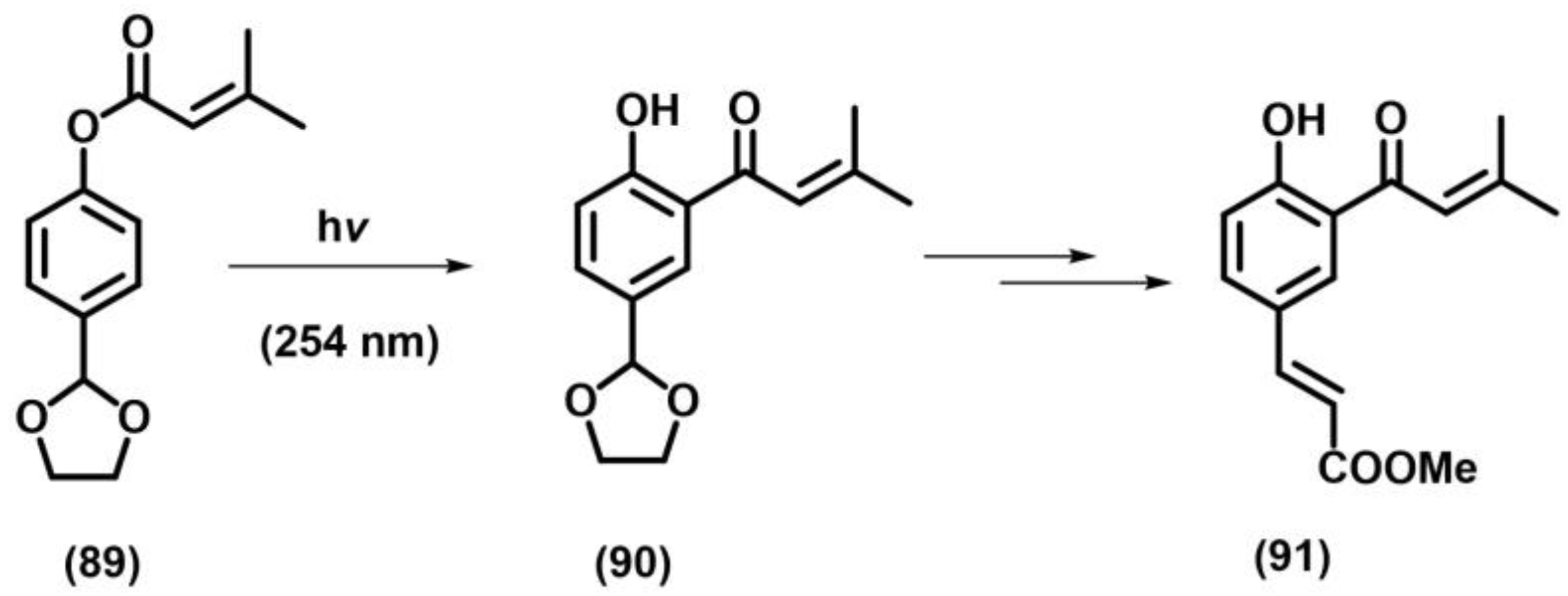

2.10.2. Photo-Fries Rearrangement

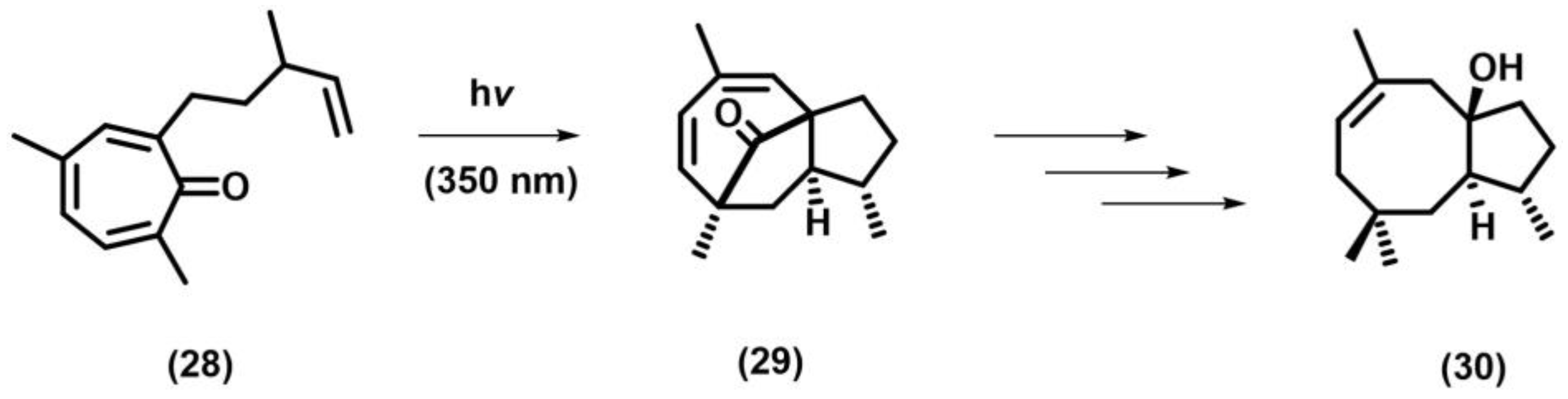

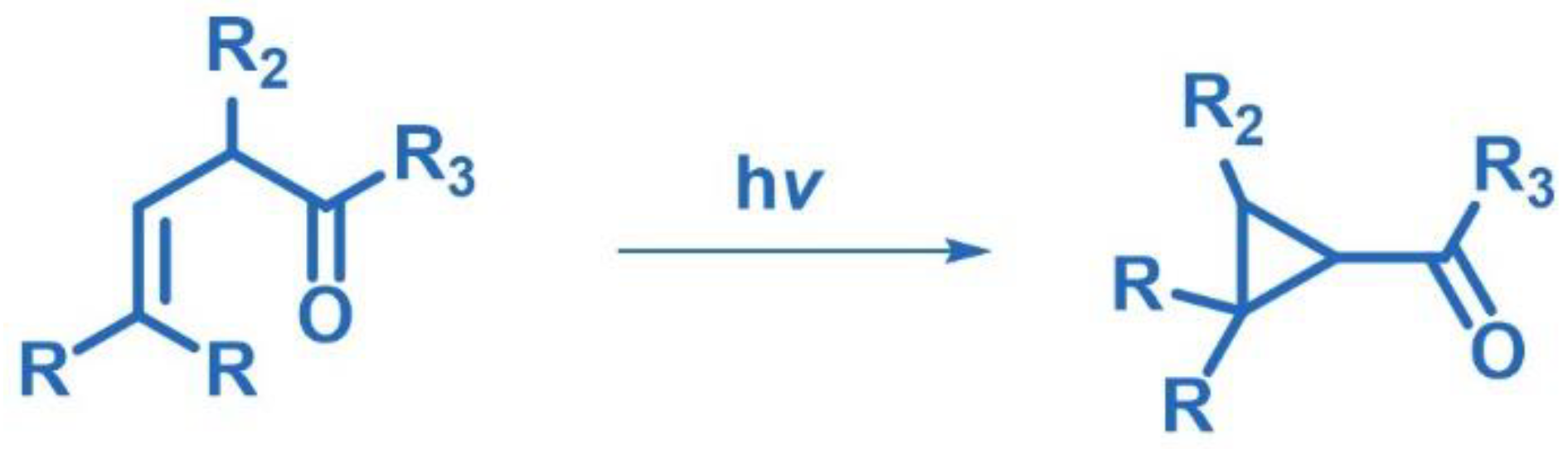

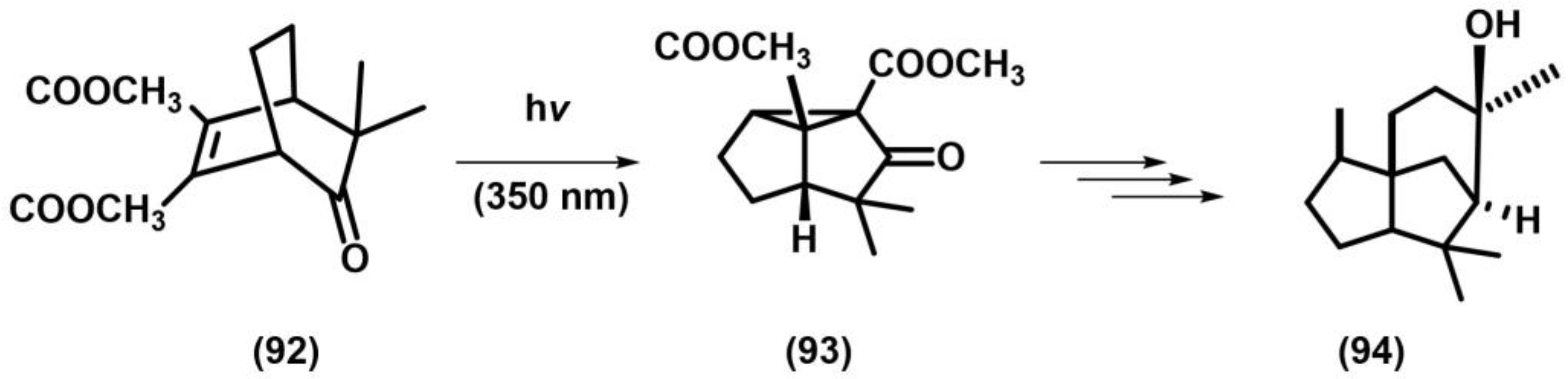

2.10.3. Oxa-di-π Methane Rearrangement

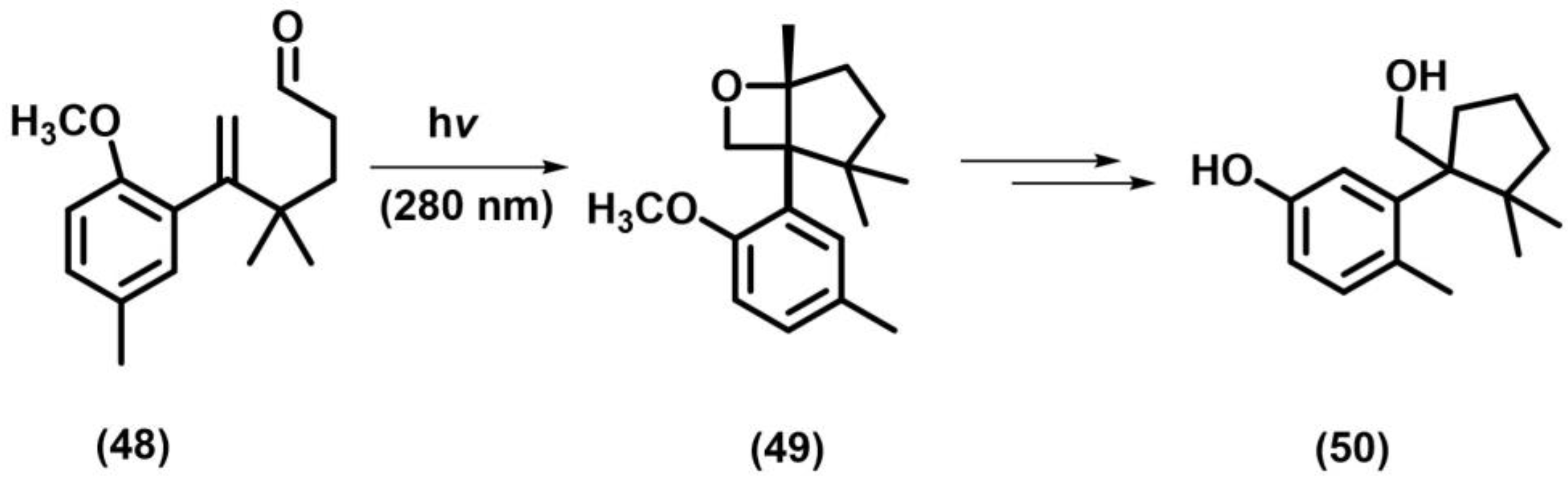

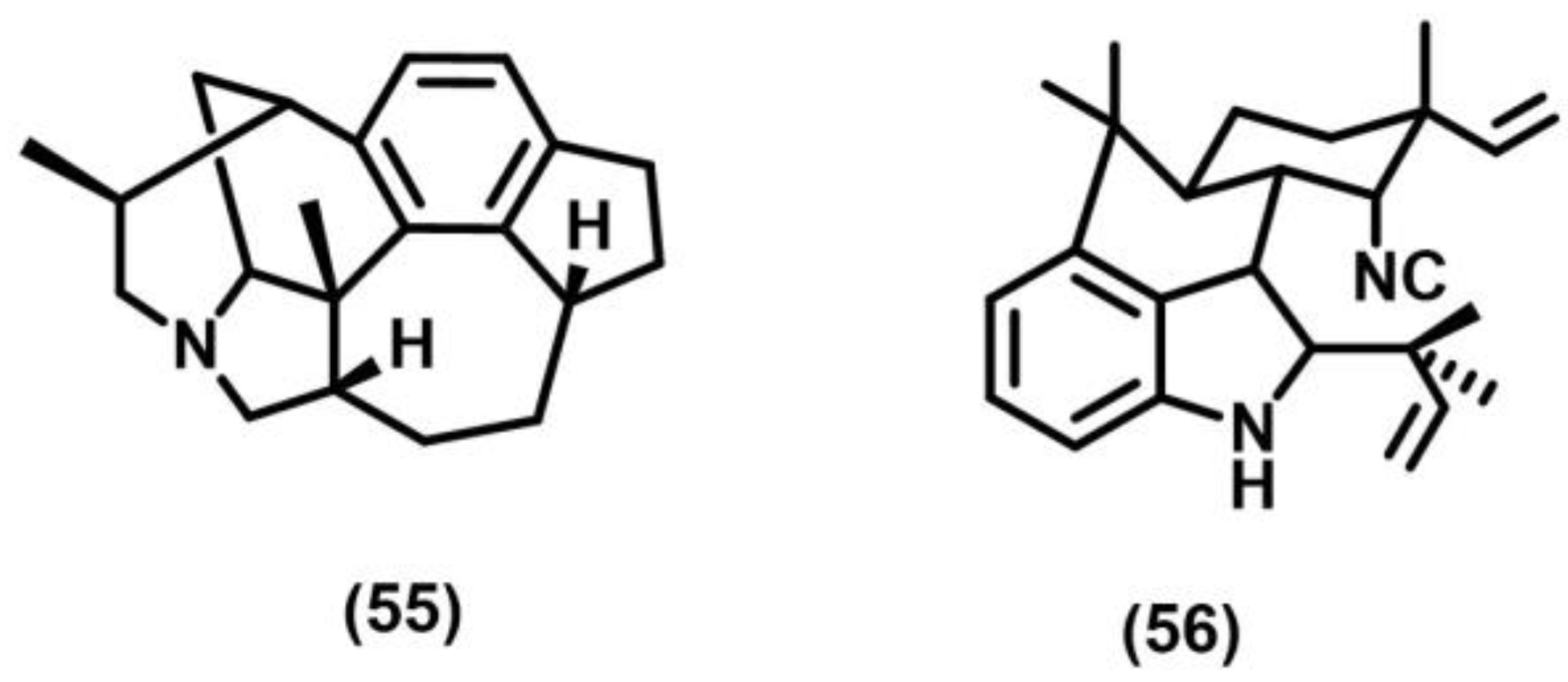

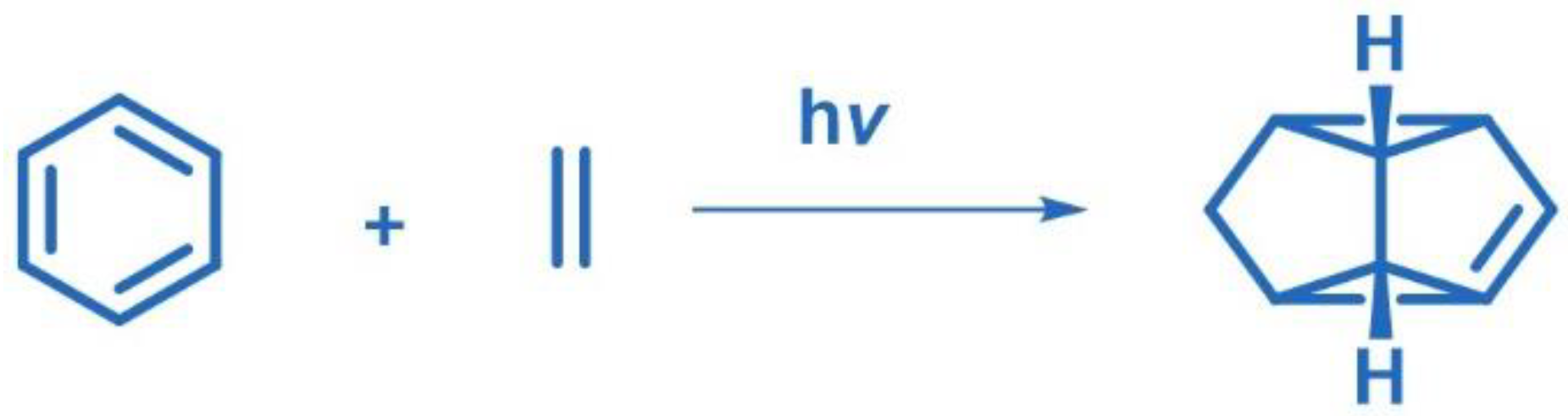

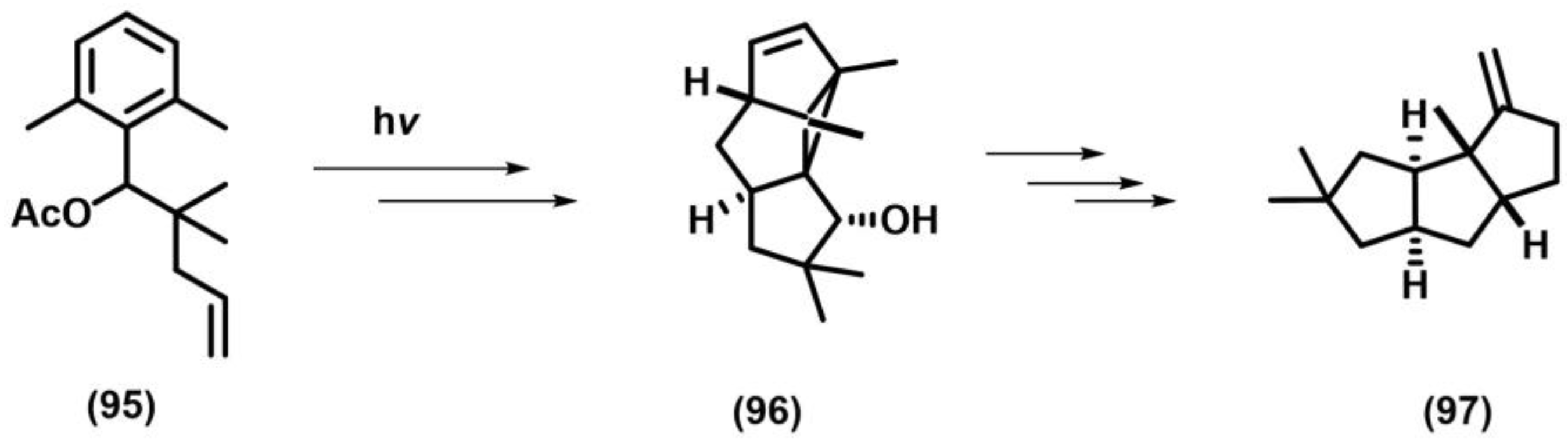

2.11. Meta Photocyclization

3. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Declaration Statement for the Use of AI

Abbreviations

| NPS | Natural Product Synthesis |

References

- Shenvi, R.A. Natural Product Synthesis in the 21st Century: Beyond the Mountain Top. ACS Cent. Sci. 2024, 10, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolaou, K.C.; Rigol, S. Total Synthesis in Search of Potent Antibody–Drug Conjugate Payloads. From the Fundamentals to the Translational. Acc. Chem. Res. 2019, 52, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuttruff, C.A.; Eastgate, M.D.; Baran, P.S. Natural product synthesis in the age of scalability. Nat. Product. Rep. 2014, 31, 419–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, D.S.; Pitts, C.R.; McClymont, K.S.; Stratton, T.P.; Bi, C.; Baran, P.S. Ideality in Context: Motivations for Total Synthesis. Acc. Chem. Res. 2021, 54, 605–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, S.; Bilal, M.; Rasool, N.; Imran, M. Photochemical reactions as synthetic tool for pharmaceutical industries. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2024, 35, 109498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciamician, G.; Silber, P. Chemische Lichtwirkungen. Berichte Dtsch. Chem. Ges. 1908, 41, 1071–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albini, A.; Fagnoni, M. Green chemistry and photochemistry were born at the same time. Green Chem. 2004, 6, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, M.H.; Twilton, J.; MacMillan, D.W.C. Photoredox Catalysis in Organic Chemistry. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 6898–6926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baran, P.S.; Maimone, T.J.; Richter, J.M. Total synthesis of marine natural products without using protecting groups. Nature 2007, 446, 404–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fay, N.; Kouklovsky, C.; de la Torre, A. Natural Product Synthesis: The Endless Quest for Unreachable Perfection. ACS Org. Inorg. Au 2023, 3, 350–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisman, S.E.; Maimone, T.J. Total Synthesis of Complex Natural Products: More Than a Race for Molecular Summits. Acc. Chem. Res. 2021, 54, 1815–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nay, B. Total synthesis: An enabling science. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2023, 19, 474–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fay, N.; Blieck, R.; Kouklovsky, C.; de la Torre, A. Total synthesis of grayanane natural products. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2022, 18, 1707–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, L.; Yu, H.; Deng, M.; Wu, F.; Jiang, Z.; Luo, T. Enantioselective Total Syntheses of Grayanane Diterpenoids: (−)-Grayanotoxin III, (+)-Principinol E, and (−)-Rhodomollein XX. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 5268–5273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, T. Synthesis of natural products and their derivatives using dynamic crystallization. Chem. Lett. 2024, 54, upae244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamura, T.; Uekusa, Y.I.H.; Matsumoto, T.; Suzuki, K. Poly-oxygenated Tricyclobutabenzenes via Repeated [2+2] Cycloaddition of Benzyne and Ketene Silyl Acetal. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 11, 3534–3535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatakeyama, S. Total Synthesis of Biologically Active Natural Products Based on Highly Selective Synthetic Methodologies. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2014, 62, 1045–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez, L.W.; Sarlah, D. Empowering Synthesis of Complex Natural Products. Chem. Eur. J. 2019, 25, 13248–13270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlinger, C.K.G.; Gaich, T. Structure-Pattern-Based Total Synthesis. Chem. Eur. J. 2019, 25, 10782–10791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, F.; Chen, Y.; Li, A. Total Synthesis of Longeracinphyllin A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 14893–14896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Xuan, J.; Rao, P.; Xie, P.P.; Hong, X.; Lin, X.; Ding, H. Total Syntheses of (+)-Sarcophytin, (+)-Chatancin, (−)-3-Oxochatancin, and (−)-Pavidolide B: A Divergent Approach. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 5100–5104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Wang, Q.; Zhu, J. Unified divergent strategy towards the total synthesis of the three sub-classes of hasubanan alkaloids. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolaou, K.C.; Sarlah, D.; Shaw, D.M. Total Synthesis and Revised Structure of Biyouyanagin A. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 4708–4711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alibés, R.; Bourdelande, J.L.; Font, J.; Parella, T. Highly efficient and diastereoselective approaches to (+)- and (−)-grandisol. Tetrahedron 1996, 52, 1279–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, G.; Sreenivas, K. A new synthesis of tricyclic sesquiterpene (±)-sterpurene. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002, 43, 703–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangion, I.K.; MacMillan, D.W.C. Total Synthesis of Brasoside and Littoralisone. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 3696–3697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srikrishna, A.; Ramasastry, S.S.V. Enantiospecific total synthesis of phytoalexins, (+)-solanascone, (+)-dehydrosolanascone, and (+)-anhydro-β-rotunol. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005, 46, 7373–7376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leimner, J.; Marschall, H.; Meier, N.; Weyerstahl, P. Italicene and Isoitalicene, Novel Sesquiterpene Hydrocarbons from Helichrysum Oil. Chem. Lett. 1984, 13, 1769–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielson, L.B.; Wege, D. The enantioselective synthesis of elecanacin through an intramolecular naphthoquinone-vinyl ether photochemical cycloaddition. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2006, 4, 868–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schell, F.M.; Cook, P.M. Intramolecular photochemistry of a vinylogous amide and some transformations of the photoproduct. J. Org. Chem. 1984, 49, 4067–4070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, J.D.; Muller, C.L.; Scott, R.D. A new method for the formation of nitrogen-containing ring systems via the intramolecular photocycloaddition of vinylogous amides. A synthesis of mesembrine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988, 110, 4831–4832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, J.D.; Li, Y.; Ihle, D.C. Tandem Intramolecular Photocycloaddition−Retro-Mannich Fragmentation as a Route to Spiro[pyrrolidine-3,3′-oxindoles]. Total Synthesis of (±)-Coerulescine, (±)-Horsfiline, (±)-Elacomine, and (±)-6-Deoxyelacomine. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 75, 3569–3577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerard, B.; Jones, G.; Porco, J.A. A Biomimetic Approach to the Rocaglamides Employing Photogeneration of Oxidopyryliums Derived from 3-Hydroxyflavones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 13620–13621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, K.S.; Wu, M.J.; Rotella, D.P. Application of an intramolecular tropone-alkene photocyclization to the total synthesis of (.+-.)-dactylol. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989, 111, 6457–6458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, K.S.; Wu, M.J.; Rotella, D.P. Total synthesis of (+-)-dactylol and related studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990, 112, 8490–8496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, T.; Hehn, J.P. Photochemical reactions as key steps in natural product synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2011, 50, 1000–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eade, S.J.; Walter, M.W.; Byrne, C.; Odell, B.; Rodriguez, R.; Baldwin, J.E.; Adlington, R.M.; Moses, J.E. Biomimetic Synthesis of Pyrone-Derived Natural Products: Exploring Chemical Pathways from a Unique Polyketide Precursor. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 4830–4839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, E.C.; Brieskorn, C.H.; Blechert, S. Isolierung und Synthese des 5-Ethyl-2-methyl-11H-pyrido [3,4-a]-carbazolium-hydroxids, ein neuer Indolalkaloidtyp aus Aspidosperma gilbertii. Chem. Berichte 1980, 113, 3245–3248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupchan, S.M.; Wormser, H.C. Tumor Inhibitors. X.1 Photochemical Synthesis of Phenanthrenes. Synthesis of Aristolochic Acid and Related Compounds2-4. J. Org. Chem. 1965, 30, 3792–3800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herbert, R.B.; Moody, C.J. A novel synthesis of (±)-tylophorine. J. Chem. Soc. D 1970, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letcher, R.M.; Wong, K.-M. Structure and synthesis of the phenanthrenes TaIV and TaVIII from Tamus communis. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1979, 1, 2449–2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghaddam, F.M.; Farimani, M.M. A simple and efficient total synthesis of (±)-danshexinkun A, a bioactive diterpenoid from Salvia miltiorrhiza. Tetrahedron Lett. 2010, 51, 540–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coote, S.C. 4-π-Photocyclization: Scope and Synthetic Applications. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 2020, 1405–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, A.; Crabbé, P. A novel approach to the synthesis of prostanoids. Tetrahedron Lett. 1975, 16, 2215–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CRC Handbook of Organic Photochemistry and Photobiology; Horspool, W.M.L.F., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.R.; Briant, C.E.; Edwards, R.L.; Mabelis, R.P.; Poyser, J.P.; Spencer, H.; Whalley, A.J. Punctatin A (antibiotic M95464): X-ray crystal structure of a sesquiterpene alcohol with a new carbon skeleton from the fungus, Paronia punctata. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1984, 7, 405–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, G.A.; Chen, L. A total synthesis of racemic paulownin using a type II photocyclization reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990, 112, 3464–3466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Mayo, P.; Suau, R. Photochemical synthesis. Part LVIII. A photochemical synthesis of (±)-cuparene. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1974, 1, 2559–2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koźluk, T.; Cottier, L.; Descotes, G. Syntheses photochimiques de dioxa-1,6 spiro [4.5] decanes pheromones de Paravespula vulgaris L. Tetrahedron 1981, 37, 1875–1880. [Google Scholar]

- Gramain, J.C.; Remuson, R.; Vallee, D. Intramolecular photoreduction of .alpha.-keto esters. Total synthesis of (±)-isoretronecanol. J. Org. Chem. 1985, 50, 710–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wessig, P.; Teubner, J. Total Synthesis of Pterosines B and C via a Photochemical Key Step. Synlett 2006, 2006, 1543–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, T.; Schröder, J. A Short Synthesis of (±)-Oxetin. Liebigs Ann. 1997, 1997, 2265–2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambalek, R.; Just, G. A short synthesis of (±)-oxetanocin. Tetrahedron Lett. 1990, 31, 5445–5448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, S.L. [2 + 2] Photocycloadditions in the Synthesis of Chiral Molecules. Science 1985, 227, 857–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schreiber, S.L.; Hoveyda, A.H. Synthetic studies of the furan-carbonyl photocycloaddition reaction. A total synthesis of (±)-avenaciolide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984, 106, 7200–7202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, S.L.; Satake, K. Total synthesis of (.+-.)-asteltoxin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984, 106, 4186–4188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boxall, R.J.; Ferris, L.; Grainger, R.S. Synthesis of C-13 Oxidised Cuparene and Herbertane Sesquiterpenes via a Paternò-Büchi Photocyclisation-Oxetane Fragmentation Strategy: Total Synthesis of 1,13-Herbertenediol. Synlett 2004, 2004, 2379–2381. [Google Scholar]

- Dotson, J.J.; Bachman, J.L.; Garcia-Garibay, M.A.; Garg, N.K. Discovery and Total Synthesis of a Bis(cyclotryptamine) Alkaloid Bearing the Elusive Piperidinoindoline Scaffold. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 11685–11690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Li, Y.; Deng, J.; Li, A. Total synthesis of the Daphniphyllum alkaloid daphenylline. Nat. Chem. 2013, 5, 679–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando, Y.; Tanaka, D.; Sasaki, R.; Ohmori, K.; Suzuki, K. Stereochemical Dichotomy in Two Competing Cascade Processes: Total Syntheses of Both Enantiomers of Spiroxin A. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 12507–12513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledford, B.E.; Carreira, E.M. Total Synthesis of (+)-Trehazolin: Optically Active Spirocycloheptadienes as Useful Precursors for the Synthesis of Amino Cyclopentitols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995, 117, 11811–11812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piva, O.; Caramelle, D. Asymmetric protonation of photodienols enantioselective synthesis of (R)-2-methyl alkanols. Tetrahedro Asymmetry 1995, 6, 831–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Mayo, P.; Takeshita, H. Photochemical syntheses: 6. The formation of heptandiones from acetylacetone and alkenes. Can. J. Chem. 1963, 41, 440–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Mayo, P.; Takeshita, H.; Sattar, A.B.M.A. The photochemical synthesis of 1,5-diketones and their cyclyzation: A new anuulation Process. Proc. Chem. Soc. 1962, 1962, 119. [Google Scholar]

- Hikino, H.; De Mayo, P. Photochemical Cycloaddition as a Device for General Annelation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1964, 86, 3582–3583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppolzer, W.; Godel, T. A new and efficient total synthesis of (.+-.)-longifolene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1978, 100, 2583–2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppolzer, W.; Godel, T. Syntheses of (±)- and Enantiomerically Pure (+)-Longifolene and of (±)- and Enantiomerically Pure (+)-Sativene by an Intramolecular de Mayo Reaction. Helv. Chim. Acta 1984, 67, 1154–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seto, H.; Fujimoto, Y.; Tatsuno, T.; Yoshioka, H. Snthetic Studies on Carotane and Dolastane Type Terpenes: A New Entry to the Total Synthesis of (±)-Daucene Via Intramolecular [2 + 2] Photocycloaddition. Synth. Commun. 1985, 15, 1217–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Disanayaka, B.W.; Weedon, A.C. A short synthesis of hirsutene using the de Mayo reaction. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1985, 19, 1282–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buechi, G.; Carlson, J.A.; Powell, J.E.; Tietze, L.F. Total synthesis of loganin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1970, 92, 2165–2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearlman, B.A. A method for effecting the equivalent of a de Mayo reaction with formyl acetic ester. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1979, 101, 6398–6404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, A.J.; Pattenden, G. Zizaane sesquiterpenes. Synthesis of the coates-sowerby tricyclic ketone. Tetrahedron Lett. 1981, 22, 2599–2600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, F.D.; Oxman, J.D.; Huffman, J.C. Photodimerization of Lewis acid complexes of cinnamate esters in solution and the solid state. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984, 106, 466–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meesakul, P.; Jaidee, W.; Richardson, C.; Andersen, R.J.; Patrick, B.O.; Willis, A.C.; Muanprasat, C.; Wang, J.; Lei, X.; Hadsadee, S.; et al. Styryllactones from Goniothalamus tamirensis. Phytochemistry 2020, 171, 112248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmerman, H.E.; Schuster, D.I. A New Approach to Mechanistic Organic Photochemistry. IV. Photochemical Rearrangements of 4,4-Diphenylcyclohexadienone. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1962, 84, 4527–4540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natarajan, A.; Tsai, C.K.; Khan, S.I.; McCarren, P.; Houk, K.N.; Garcia-Garibay, M.A. The photoarrangement of alpha-santonin is a single-crystal-to-single-crystal reaction: A long kept secret in solid-state organic chemistry revealed. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 9846–9847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karkas, M.D.; Porco, J.A., Jr.; Stephenson, C.R. Photochemical Approaches to Complex Chemotypes: Applications in Natural Product Synthesis. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 9683–9747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bos, P.H.; Antalek, M.T.; Porco, J.A., Jr.; Stephenson, C.R. Tandem dienone photorearrangement-cycloaddition for the rapid generation of molecular complexity. J Am Chem Soc 2013, 135, 17978–17982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lochbrunner, S.; Zissler, M.; Piel, J.; Riedle, E.; Spiegel, A.; Bach, T. Real time observation of the photo-Fries rearrangement. J. Chem. Phys. 2004, 120, 11634–11639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taub, D.; Kuo, C.H.; Slates, H.L.; Wendler, N.L. A total synthesis of griseofulvin and its optical antipode. Tetrahedron 1963, 19, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kende, A.S.; Belletire, J.L.; Hume, E.L. Regiospecific synthesis of 1,4,5-trioxygenated anthraquinones. A total synthesis of islandicin. Tetrahedron Lett. 1973, 14, 2935–2938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, T.; Katagiri, N.; Nakano, J.; Kawamura, H. Total synthesis of bikaverin involving the novel rearrangement of an ortho-quinone to a para-quinone. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1977, 18, 645–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farina, F.; Martinez-Utrilla, R.; Paredes, M.C. Polycyclic hydroxyquinones—VIII: Preparation of acetylhydroxynaphthazarins by photo-fries rearrangement. A convenient synthesis of spinochrome A. Tetrahedron 1982, 38, 1531–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, M.A.; Primo, J.; Tormos, R. Studies on the Synthesis of Precocenes. The Photo-Fries Rearrangement of Esters of α,β-Unsaturated Carboxylic Acids and meta-Oxygenated Phenols. ChemInform 1988, 19, 673–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suau, R.; Valpuesta, M.; Torres, G. Photochemical synthesis of 7,8-dioxygenated isoquinoline alkaloids. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995, 36, 1315–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stork, G.; Clarke, F.H., Jr. Cedrol: Stereochemistry and Total Synthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1961, 83, 3114–3125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demuth, M.; Hinsken, W. Extensions of the Tricyclooctanone Concept. A General Principle for the Synthesis of Linearly and Angularly Annelated Triquinanes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1985, 24, 973–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, D.S.; Chou, Y.Y.; Tung, Y.S.; Liao, C.C. Photochemistry of Tricyclo [5.2.2.02,6]undeca-4,10-dien-8-ones: An Efficient General Route to Substituted Linear Triquinanes from 2-Methoxyphenols. Total Synthesis of (±)-Δ9(12)-Capnellene. Chem. Eur. J. 2010, 16, 3121–3131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reekie, T.A.; Austin, K.A.; Banwell, M.G.; Willis, A.C. The Chemoenzymatic Total Synthesis of Phellodonic Acid, a Biologically Active and Highly Functionalized Hirsutane Derivative Isolated from the Tasmanian Fungus Phellodon melaleucus. Aust. J. Chem. 2008, 61, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banwell, M.G.; Edwards, A.J.; Harfoot, G.J.; Jolliffe, K.A. A chemoenzymatic synthesis of (−)-hirsutene from toluene. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 2002, 22, 2439–2441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, K.A.; Banwell, M.G.; Harfoot, G.J.; Willis, A.C. Chemoenzymatic syntheses of the linear triquinane-type sesquiterpenes (+)-hirsutic acid and (−)-complicatic acid. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006, 47, 7381–7384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wender, P.A.; Howbert, J.J. Synthetic studies on arene-olefin cycloadditions-III-total synthesis of (±)-hirsutene. Tetrahedron Lett. 1982, 23, 3983–3986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wender, P.A.; Howbert, J.J. Synthetic studies on areneolefin cycloadditions-VI-two syntheses of (±)-coriolin. Tetrahedron Lett. 1983, 24, 5325–5328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baralotto, C.; Chanon, M.; Julliard, M. Total Synthesis of the Tricyclic Sesquiterpene (±)-Ceratopicanol. An Illustration of the Holosynthon Concept. J. Org. Chem. 1996, 61, 3576–3577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wender, P.A.; Dreyer, G.B. Synthetic studies on arene-olefin cycloadditions-V. total synthesis of (±)-isoiridomyrmecin. Tetrahedron Lett. 1983, 24, 4543–4546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gupta, S. Application of Photochemistry in Natural Product Synthesis: A Sustainable Frontier. Photochem 2025, 5, 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/photochem5040039

Gupta S. Application of Photochemistry in Natural Product Synthesis: A Sustainable Frontier. Photochem. 2025; 5(4):39. https://doi.org/10.3390/photochem5040039

Chicago/Turabian StyleGupta, Shipra. 2025. "Application of Photochemistry in Natural Product Synthesis: A Sustainable Frontier" Photochem 5, no. 4: 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/photochem5040039

APA StyleGupta, S. (2025). Application of Photochemistry in Natural Product Synthesis: A Sustainable Frontier. Photochem, 5(4), 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/photochem5040039