Traditional Medicine and the Pangolin Trade: A Review of Drivers and Conservation Challenges

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Biology, Distribution, and Conservation Status of Pangolins

3. Historical Context and Cultural Significance of Pangolins in Traditional Medicine

3.1. Asian Traditional Medicine Systems

3.2. African Ethnomedical Systems

4. Biomedical Rationale: Investigating Therapeutic Claims

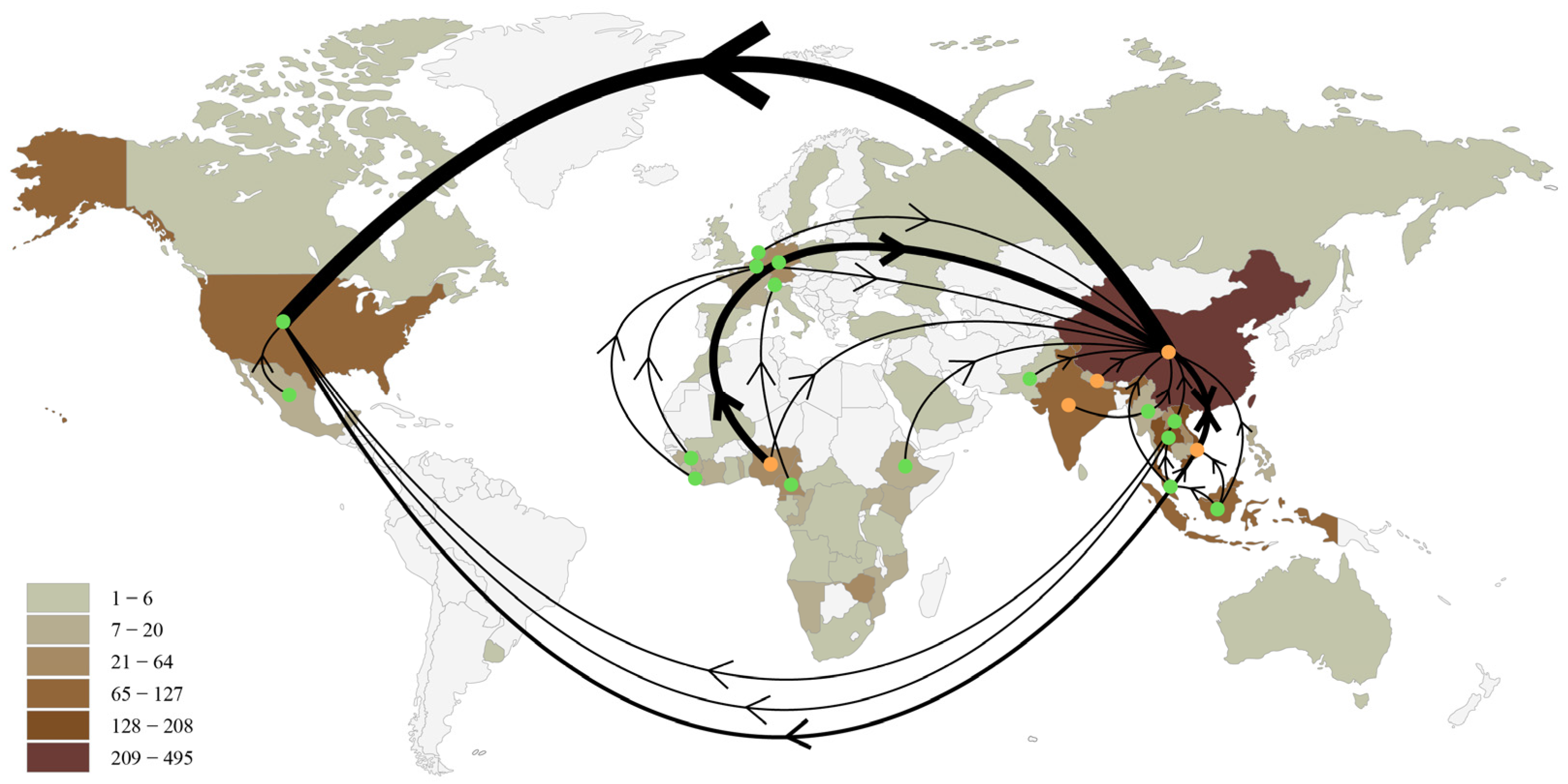

5. Illegal Wildlife Trade: Scale and Dynamics

6. Impact on Pangolin Populations and Ecosystems

7. Recommendations to Address the Challenge: Conservation and Alternatives

- Population Assessment: The global determination of the size and status of isolated pangolin populations globally, prioritizing countries with high traditional medicine use and trafficking hubs (e.g., China, Vietnam, Nepal, Hong Kong, Singapore, Malaysia, Nigeria, DRC, and Cameroon), is essential. Such studies will provide critical insights into distribution, dynamics, and threats, enabling targeted conservation [22].

- Trade Quantification and Monitoring: Quantifying the number of pangolins sold and utilized and assessing the scale of global trade is important to conserve the animals, while local use has been studied [39,44,52]. Intercontinental trafficking research is scarcer [39,44,46]. A global pangolin seizure database is needed to track species, sources, trade patterns, and routes. Robust tracking systems in TCM (e.g., blockchain, electronic tagging) could ensure transparency and prevent illegal products from entering legal markets, supported by regular audits and inspections.

- Demand Reduction and Alternatives: It is essential to address the demand for pangolins in traditional medicine by promoting scientifically validated synthetic or alternative medicinal products that mimic purported benefits without harming animals. For example, in TCM, herbal substitutes like “blood-activating” plants such as safflower (Carthamus tinctorius) have been promoted as alternatives to pangolin scales [23].

- Strengthened Law Enforcement and Legislation: Enhancing law enforcement and national legislation in countries where pangolins are originally found and now exist is essential. Impose higher fines, stricter penalties, and other punitive measures for trafficking. Foster international cooperation among law enforcement agencies, improve cross-border intelligence sharing, and provide specialized training for officers on wildlife crime identification and response [51,53,54].

- Conservation Initiatives: Initiatives such as the establishment of pangolin sanctuaries and the exploration of ethically managed ex situ conservation programs are critical. Acknowledging the significant challenges and low success rates of captive breeding is important, and such efforts should prioritize animal welfare in conserving these sensitive species. It is important to establish pangolin sanctuaries, specialized rescue and rehabilitation centres, and ex situ conservation breeding programs, particularly in African and Asian countries where pangolins are known to exist historically. These are critical for safeguarding populations from extinction [23,50,53].

- Community Awareness and Engagement: It is vital to raise awareness among local communities on pangolin conservation status, relevant national laws, and the unsustainable nature of their use in medicine, food, and other sectors. This is essential for reducing exploitation and fostering local stewardship [54,55].

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CITES | Convention on international trade in endangered species of wild fauna and flora. |

| IUCN | International Union for Conservation of Nature. |

| TCM | Traditional Chinese medicine |

| TVM | Traditional Vietnamese medicine |

| RCT | Randomized controlled trial |

References

- Cordell, G.A. The contemporary nexus of medicines security and bioprospecting: A future perspective for prioritizing the patient. Nat. Prod. Bioprospect. 2024, 14, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, M.G. Cultural epidemiology: An introduction and overview. Anthropol. Med. 2001, 8, 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, R.R.; Alves, H.N. The faunal drugstore: Animal-based remedies used in traditional medicines in Latin America. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2011, 7, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Still, J. Use of animal products in traditional Chinese medicine: Environmental impact and health hazards. Complement. Ther. Med. 2003, 11, 118–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiting, M.J.; Williams, V.L.; Hibbitts, T.J. Animals Traded for Traditional Medicine at the Faraday Market in South Africa: Species Diversity and Conservation Implications. In Animals in Traditional Folk Medicine; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 421–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waheed, H.; Moin, S.F.; Choudhary, M.I. Snake Venom: From Deadly Toxins to Life-saving Therapeutics. Curr. Med. Chem. 2017, 24, 1874–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safavi-Hemami, H.; Brogan, S.E.; Olivera, B.M. Pain therapeutics from cone snail venoms: From Ziconotide to novel non-opioid pathways. J. Proteom. 2019, 190, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markwardt, F. Hirudin as alternative anticoagulant–a historical review. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2002, 28, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furman, B.L. The development of Byetta (exenatide) from the venom of the Gila monster as an anti-diabetic agent. Toxicon 2012, 59, 464–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, S.; Bonebreak, T.C.; Cheng, W.; Zhang, M.; Ades, G.; Shaw, D.; Zhou, Y. PANGOLINS: Science and Conservation; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 227–239. [Google Scholar]

- Kakati, L.N.; Doulo, V. Indigenous Knowledge System of Zootherapeutic Use by Chakhesang Tribe of Nagaland, India. J. Hum. Ecol. 2002, 13, 419–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Kamali, H.H. Folk medicinal use of some animal products in Central Sudan. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2000, 72, 279–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, D.; Wu, K.; Nie, A. China’s Legal Protection System for Pangolins: Past, Present, and Future. Animals 2025, 15, 2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Species 2023 Report of the IUCN Species Survival Commission and Secretariat Stand-Alone Report IUCN SSC Pangolin Specialist Group ISSUE 64. Available online: https://iucn.org/sites/default/files/2024-10/2023-iucn-ssc-pangolin-sg-report_publication.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Liu, Y.; Weng, Q. Fauna in decline: Plight of the pangolin. Science 2014, 345, 884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aisher, A. Scarcity, alterity and value: Decline of the pangolin, the world’s most trafficked mammal. Conserv. Soc. 2016, 14, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaubert, P.; Antunes, A.; Meng, H.; Miao, L.; Peigné, S.; Justy, F.; Njiokou, F.; Dufour, S.; Danquah, E.; Alahakoon, J.; et al. The Complete Phylogeny of Pangolins: Scaling up Resources for the Molecular Tracing of the Most Trafficked Mammals on Earth. J. Hered. 2018, 109, 347–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, N.C.-M.; Lo, F.H.-Y.; Chan, F.-T.; Lin, K.-S.; Pei, K.J.-C. Inconsistent reproductive cycles and postnatal growth between captive and wild Chinese pangolins and its conservation implications. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2024, 54, e03057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietersen, D.W.; Fisher, J.T.; Glennon, K.L.; Murray, K.A.; Parrini, F. Distribution of Temminck’s pangolin (Smutsia temminckii) in South Africa, with evaluation of questionable historical and contemporary occurrence records. Afr. J. Ecol. 2021, 59, 597–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panta, M.; Dhami, B.; Shrestha, B.; Kc, N.; Raut, N.; Timilsina, Y.P.; Chhetri, B.B.K.; Khanal, S.; Adhikari, H.; Varachova, S.; et al. Habitat preference and distribution of Chinese pangolin and people’s attitude to its conservation in Gorkha District, Nepal. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 11, 1081385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xian, Y.; Lu, Y.; Liu, G. Is climate change threatening or beneficial to the habitat distribution of global pangolin species? Evidence from species distribution modeling. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 811, 151385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heighton, S.P.; Gaubert, P. A timely systematic review on pangolin research, commercialization, and popularization to identify knowledge gaps and produce conservation guidelines. Biol. Conserv. 2021, 256, 109042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Turvey, S.T.; Leader-Williams, N. Knowledge and attitudes about the use of pangolin scale products in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) within China. People Nat. 2020, 2, 903–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, L.; Leupen, B. The trade of African pangolins to Asia: A brief case study of pangolin shipments from Nigeria. TRAFFIC Bull. 2016, 28, 3–5. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F.; Wu, S.; Cen, P. The past, present and future of the pangolin in Mainland China. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2022, 33, e01995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pangolin Scale Seizures at All-Time High in 2019, Showing Illegal Trade Still Booming. Animals. 2020. Available online: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/article/pangolin-scale-seizures-all-time-high-2019 (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Chin, S.Y.; Pantel, S. Proceedings of the Workshop on Trade and Conservation of Pangolins Native to South and Southeast Asia, 30 June–2 July 2008, Singapore Zoo, Singapore; TRAFFIC Southeast Asia eBooks; TRAFFIC Southeast Asia: Petaling Jaya, Malaysia, 2009; pp. 66–74. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, X. Evidence for the medicinal value of Squama Manitis (pangolin scale): A systematic review. Integr. Med. Res. 2021, 10, 100486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katuwal, H.B.; Neupane, K.R.; Adhikari, D.; Sharma, M.; Thapa, S. Pangolins in eastern Nepal: Trade and ethno-medicinal importance. J. Threat. Taxa 2015, 7, 7563–7567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sexton, R.; Nguyen, T.; Roberts, D.L. The Use and Prescription of Pangolin in Traditional Vietnamese Medicine. Trop. Conserv. Sci. 2021, 14, 194008292098575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boakye, M.K.; Pietersen, D.W.; Kotzé, A.; Dalton, D.L.; Jansen, R. Ethnomedicinal use of African pangolins by traditional medical practitioners in Sierra Leone. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2014, 10, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boakye, M.K.; Pietersen, D.W.; Kotzé, A.; Dalton, D.-L.; Jansen, R. Knowledge and Uses of African Pangolins as a Source of Traditional Medicine in Ghana. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0117199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiyewu, A.O.; Boakye, M.K.; Kotzé, A.; Dalton, D.L.; Jansen, R. Ethnozoological Survey of Traditional Uses of Temminck’s Ground Pangolin (Smutsia temminckii) in South Africa. Soc. Anim. 2018, 26, 306–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanvo, S.; Djagoun, S.C.A.M.; Azihou, F.A.; Djossa, B.; Sinsin, B.; Gaubert, P. Ethnozoological and commercial drivers of the pangolin trade in Benin. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2021, 17, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Q.; Li, M.J.; Zhou, G.L. The Clinical Effect of Squam Manitis Powder on Mesenteric Lym- 479 phadenitis in Children. Chin. J. Tradit. Med. Sci. Technol. 2013, 20, 412–413. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, D.; Coscione, A.; Li, L.; Zeng, B.-Y. Effect of Chinese Herbal Medicine on Male Infertility. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 2017, 135, 297–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L. The Clinical Efficacy of Squam Manitis Powder Combined with Antibiotics in the 482 Treatment of Acute Mastitis. Hejiang J. Integr. Trad. Chin. West Med. 2011, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Challender, D.; Baillie, J.; Ades, G.; Kaspal, P.; Chan, B.; Khatiwada, A.; Xu, L.; Chin, S.; KC, R.; Nash, H. Manis pentadactyla, Chinese Pangolin. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2014, e.T12764A45222544. Available online: https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/12764/45222544 (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Omifolaji, J.K.; Hughes, A.C.; Ibrahim, A.S.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, S.; Ikyaagba, E.T.; Luan, X. Dissecting the illegal pangolin trade in China: An insight from seizures data reports. Nat. Conserv. 2022, 46, 17–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BERNAMA Pangolin Scales Still Sought-After for Use in Traditional Medicine. BERNAMA. 2025. Available online: https://www.bernama.com/en/news.php?id=2394862 (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Xu, L.; Guan, J.; Lau, W.; Xiao, Y. An Overview of Pangolin Trade in China. 2016. Available online: https://www.traffic.org/site/assets/files/10569/pangolin-trade-in-china.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Bashyal, A.; Shrestha, N.; Dhakal, A.; Khanal, S.N.; Shrestha, S. Illegal Trade in Pangolins in Nepal: Extent and Network. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2021, 32, e01940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hance, J. Five Tons of Frozen Pangolin: Indonesian Authorities Make Massive Bust. Mongabay Environmental News. 2015. Available online: https://news.mongabay.com/2015/04/five-tons-of-frozen-pangolin-indonesian-authorities-make-massive-bust/ (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Ingram, D.J.; Cronin, D.T.; Challender, D.W.S.; Venditti, D.M.; Gonder, M.K. Characterising trafficking and trade of pangolins in the Gulf of Guinea. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2019, 17, e00576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emogor, C.A.; Ingram, D.J.; Coad, L.; Worthington, T.A.; Dunn, A.; Imong, I.; Balmford, A. The scale of Nigeria’s involvement in the trans-national illegal pangolin trade: Temporal and spatial patterns and the effectiveness of wildlife trade regulations. Biol. Conserv. 2021, 264, 109365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mambeya, M.M.; Baker, F.; Momboua, B.R.; Koumba Pambo, A.F.; Hega, M.; Okouyi Okouyi, V.J.; Onanga, M.; Challender, D.W.S.; Ingram, D.J.; Wang, H.; et al. The emergence of a commercial trade in pangolins from Gabon. Afr. J. Ecol. 2018, 56, 601–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soewu, D.A.; Ayodele, I.A. Utilisation of Pangolin (Manis sps) in traditional Yorubic medicine in Ijebu province, Ogun State, Nigeria. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2009, 5, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Challender, D.; Hywood, L. African Pangolins under Increased Pressure from Poaching and Intercontinental Trade. TRAFFIC Bull. 2012, 24, 53–55. [Google Scholar]

- Newton, P.; Nguyen, T.; Roberton, S.; Bell, D. Pangolins in peril: Using local hunters’ knowledge to conserve elusive species in Vietnam. Endanger. Species Res. 2008, 6, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subba, A.; Tamang, G.; Lama, S.; Limbu, J.H.; Basnet, N.; Kyes, R.C.; Khanal, L. Habitat Occupancy of the Critically Endangered Chinese Pangolin (Manis pentadactyla) Under Human Disturbance in an Urban Environment: Implications for Conservation. Ecol. Evol. 2024, 14, e70726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xi, F.; Chao, X.; Wu, S.; Zhang, F. Curbing the trade in pangolin scales in China by revealing the characteristics of the illegal trade network. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanvo, S.; Gaubert, P.; Djagoun, C.A.M.S.; Azihou, A.F.; Djossa, B.; Sinsin, B. Assessing the spatiotemporal dynamics of endangered mammals through local ecological knowledge combined with direct evidence: The case of pangolins in Benin (West Africa). Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2020, 23, e01085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challender, D.W.S.; Embolo, L.E.; Iflankoy, C.K.M.L.; Mouafo, A.D.T.; Simo, F.T.; Ullmann, T.; Shirley, M.H. Incentivizing pangolin conservation: Decisions at CITES CoP19 may reduce conservation options for pangolins. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 2024, 6, e13117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CITES. Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora: Official Document; CITES Secretariat: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.; Stoner, K.J.; Lee, A.T.L.; Clark, S.G. Rhino horn trade in China: An analysis of the art and antiques market. Biol. Conserv. 2016, 201, 343–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Species | Common Name | Region | IUCN Red Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Manis javanica (Desmarest, 1882) | Sunda pangolin | Asia | Critically endangered |

| Manis culionensis (de Elera, 1895) | Philippine pangolin | Asia | Critically endangered |

| Manis pendadactyla (Linnaeus, 1758) | Chinese pangolin | Asia | Critically endangered |

| Manis crassicaudata (Gray, 1827) | Indian pangolin | Asia | Endangered |

| Manis gigantea (Illiger, 1815) | Giant pangolin | Africa | Endangered |

| Manis tricuspis (Rafinesque, 1821) | White-bellied pangolin | Africa | Endangered |

| Smutsia temminckii (Smuta, 1832) | Ground pangolin | Africa | Vulnerable |

| Phataginus tetradactyla (Linnaeus, 1766) | Black-billed pangolin | Africa | Vulnerable |

| Region/System | Body Part | Most Frequently Reported Ailments | Source(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) | Scales, Blood | Lactation, Arthritis, Skin disease, Blood stagnation | [21,22] |

| Traditional Vietnamese Medicine (TVM) | Scales, Meat | Detox, Rheumatism, Asthma, Cancer | [23] |

| Yorubic Medicine (Nigeria) | Scales, Organs | Fever, Infertility, Warding off evil, Money rituals | [24] |

| Nepalese Traditional Medicine | Meat, Scales | Gastrointestinal issues, Pain during pregnancy | [25] |

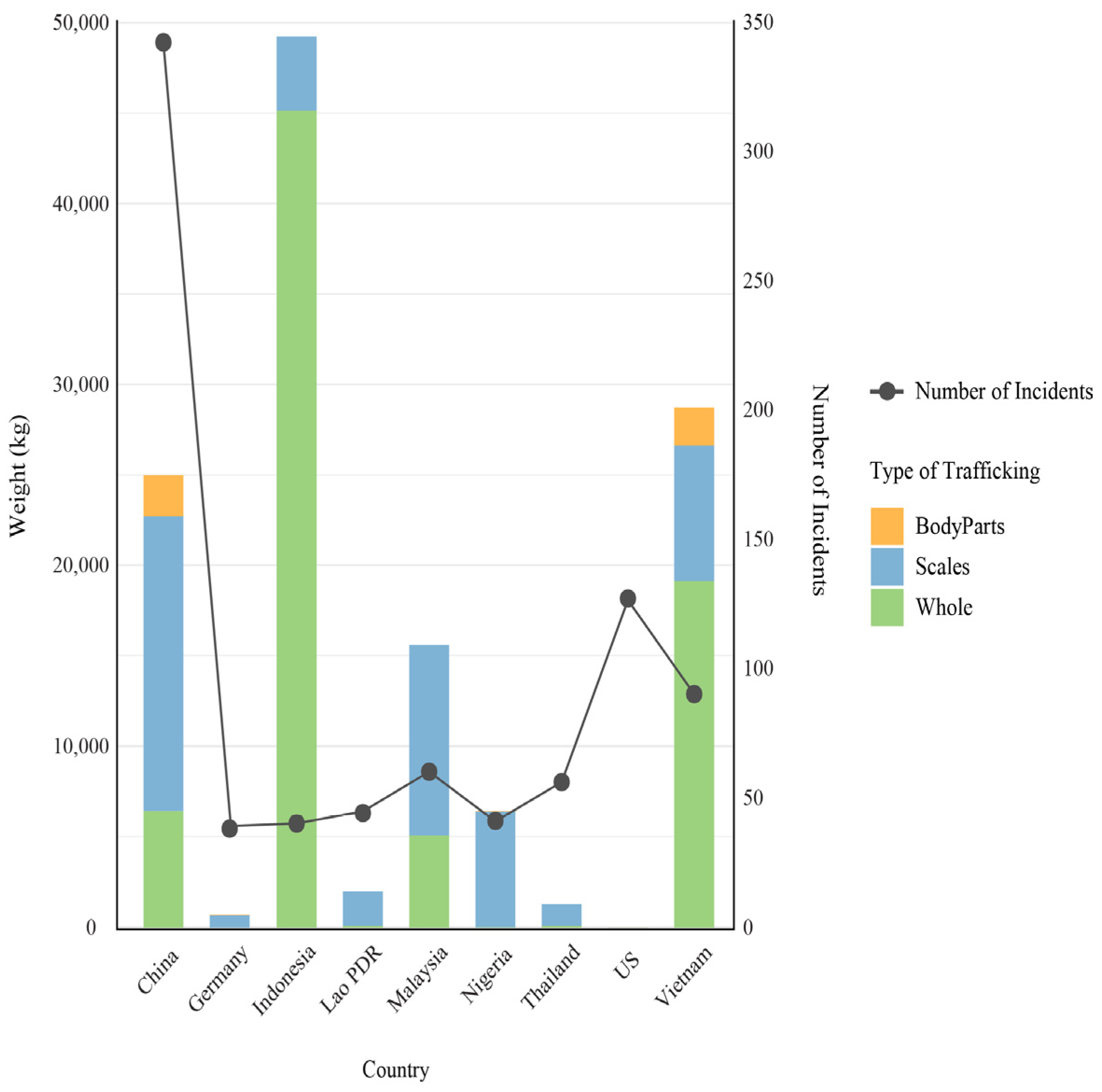

| Country | Commodity Quantities | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Incidents | Scales (kg) | Body Parts (kg) | Whole (kg) | |

| China | 399 | 23,438.6 | 2290.4 | 7007.5 |

| US | 127 | 1.4 | 5.1 | - |

| Vietnam | 90 | 7487 | 2119.1 | 19,125.3 |

| Malaysia | 60 | 10,534.3 | - | 19,125.3 |

| Thailand | 56 | 1222.2 | - | 61 |

| Lao PDR | 44 | 1914 | - | 61 |

| Nigeria | 41 | 6372.7 | 26.2 | 10.4 |

| Indonesia | 40 | 4103.4 | - | 45,140.3 |

| Germany | 38 | 666.5 | 26.2 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kodikara, C.; Gunawardane, D.; Warakapitiya, D.; Perera, M.; Peiris, D.C. Traditional Medicine and the Pangolin Trade: A Review of Drivers and Conservation Challenges. Conservation 2025, 5, 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/conservation5040077

Kodikara C, Gunawardane D, Warakapitiya D, Perera M, Peiris DC. Traditional Medicine and the Pangolin Trade: A Review of Drivers and Conservation Challenges. Conservation. 2025; 5(4):77. https://doi.org/10.3390/conservation5040077

Chicago/Turabian StyleKodikara, Chamali, Dilara Gunawardane, Dasangi Warakapitiya, Minoli Perera, and Dinithi C. Peiris. 2025. "Traditional Medicine and the Pangolin Trade: A Review of Drivers and Conservation Challenges" Conservation 5, no. 4: 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/conservation5040077

APA StyleKodikara, C., Gunawardane, D., Warakapitiya, D., Perera, M., & Peiris, D. C. (2025). Traditional Medicine and the Pangolin Trade: A Review of Drivers and Conservation Challenges. Conservation, 5(4), 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/conservation5040077