Characteristics of Beaver Activity in Bulgaria and Testing of a UAV-Based Method for Its Detection

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

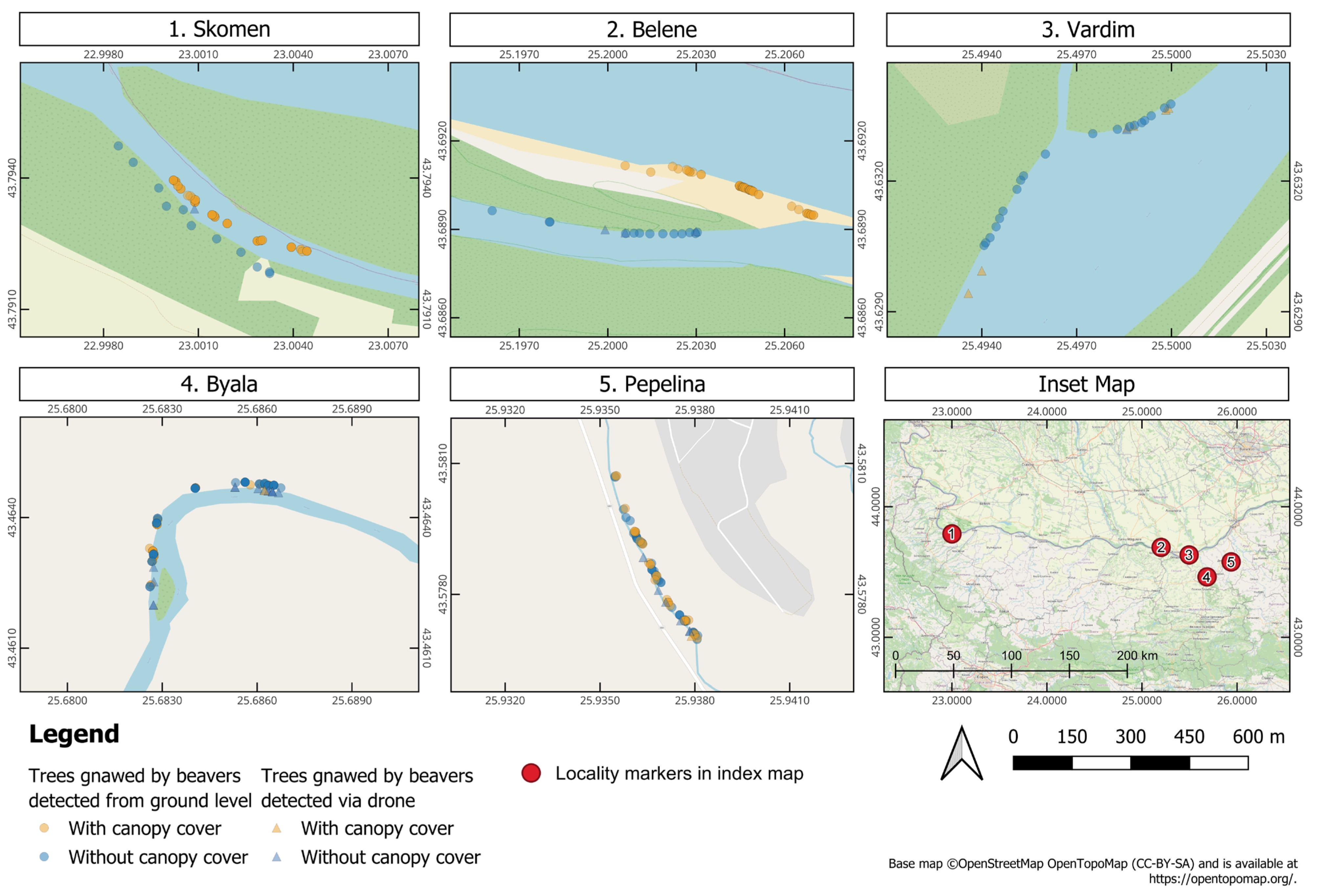

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

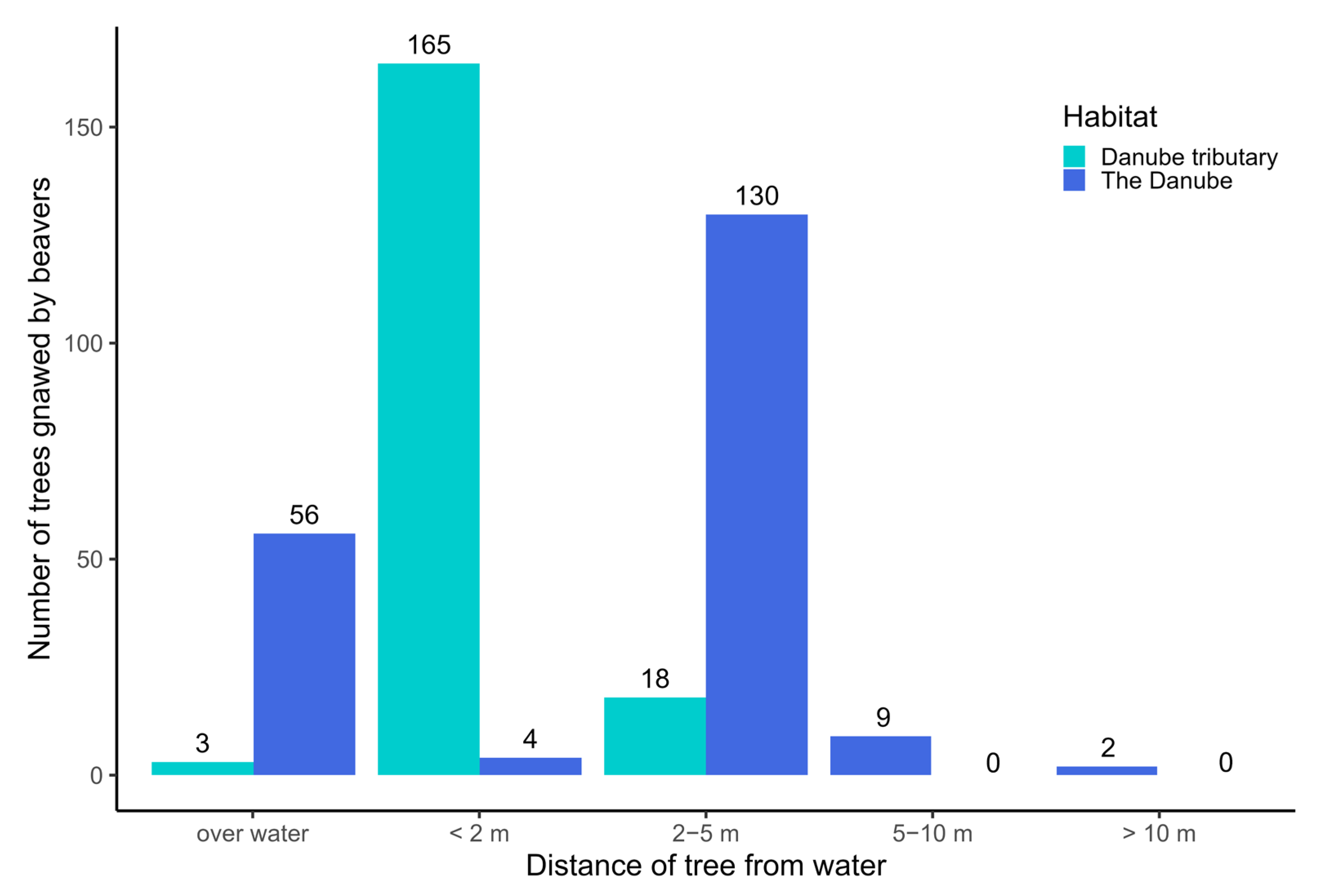

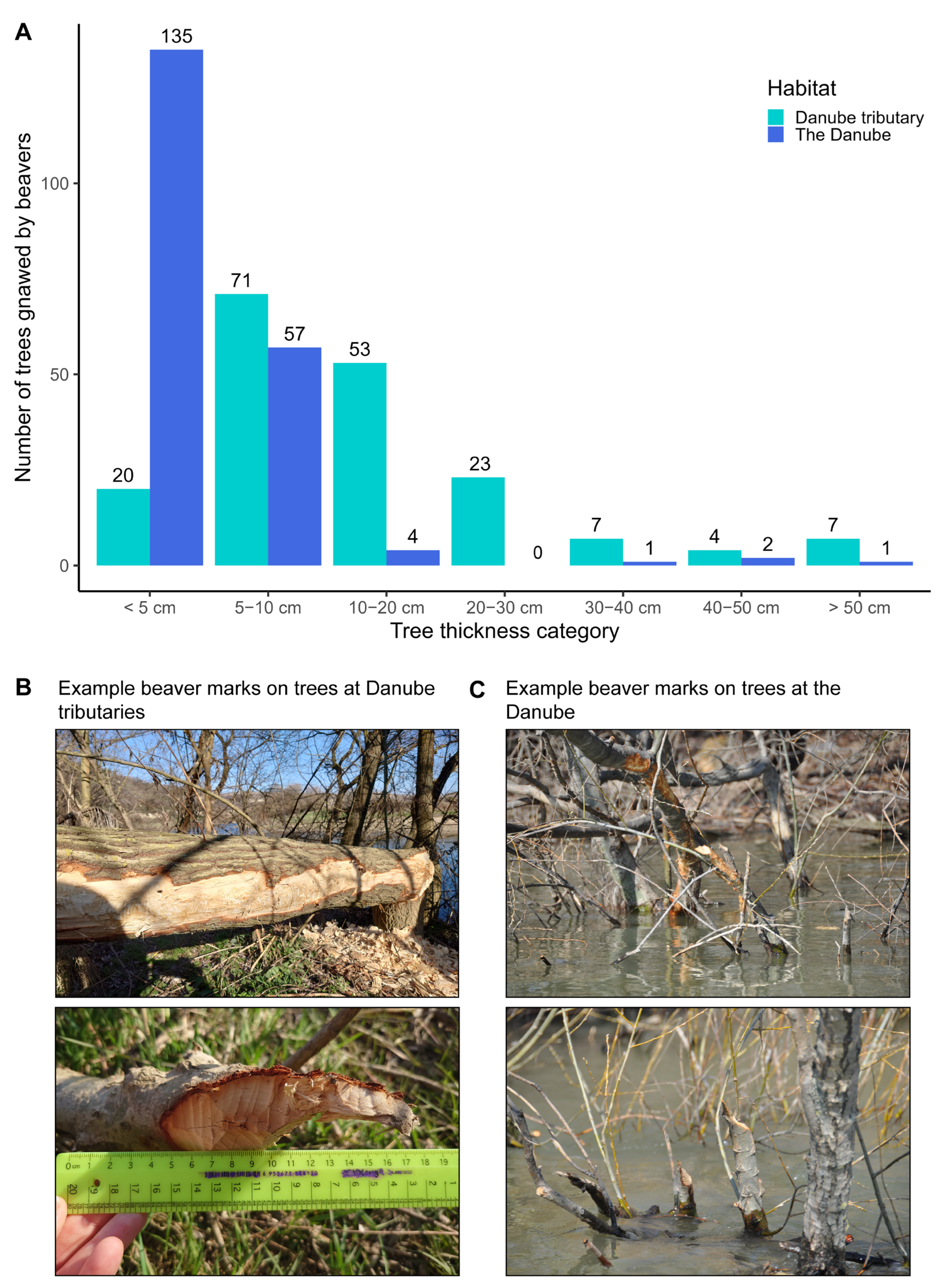

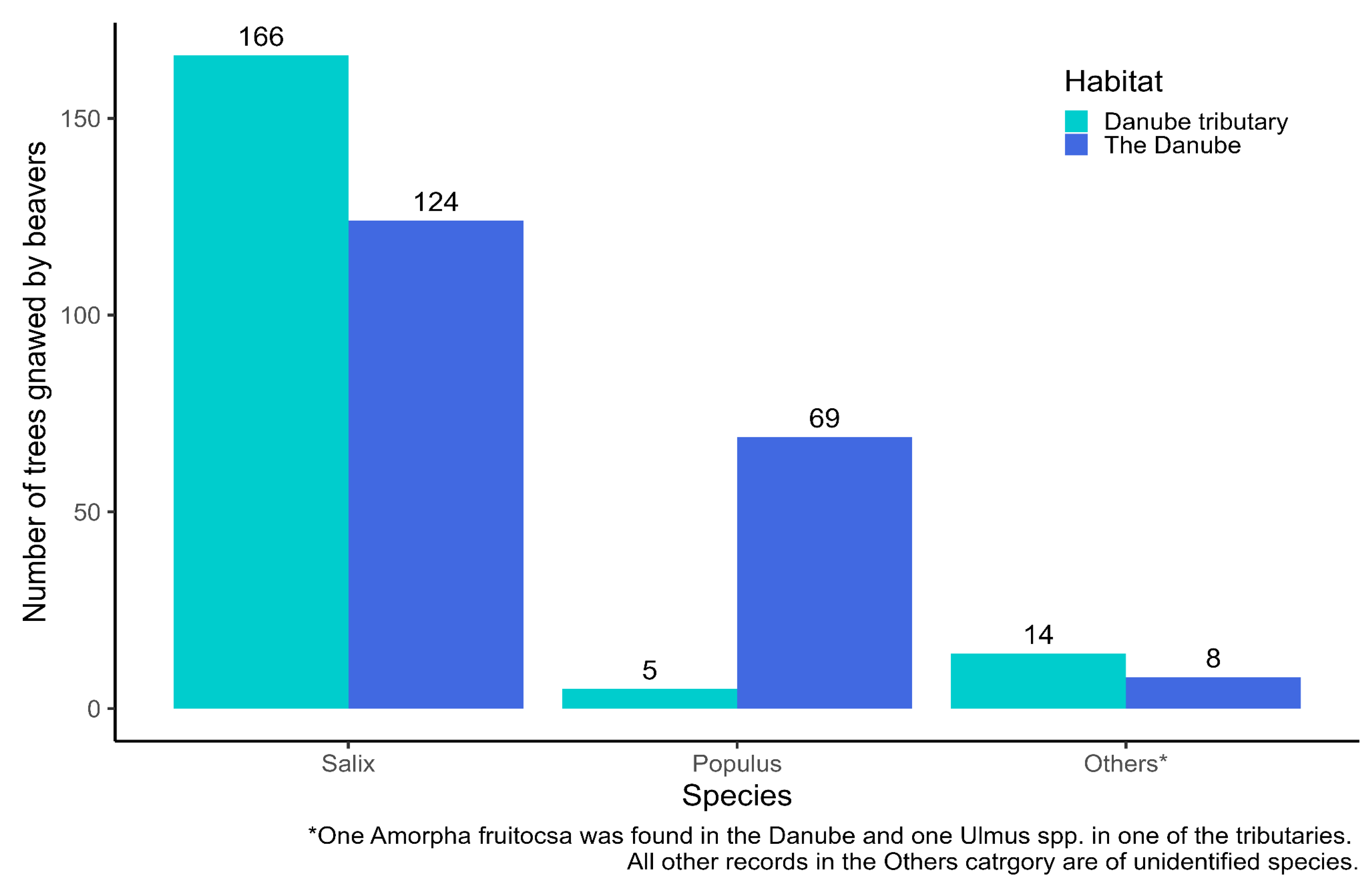

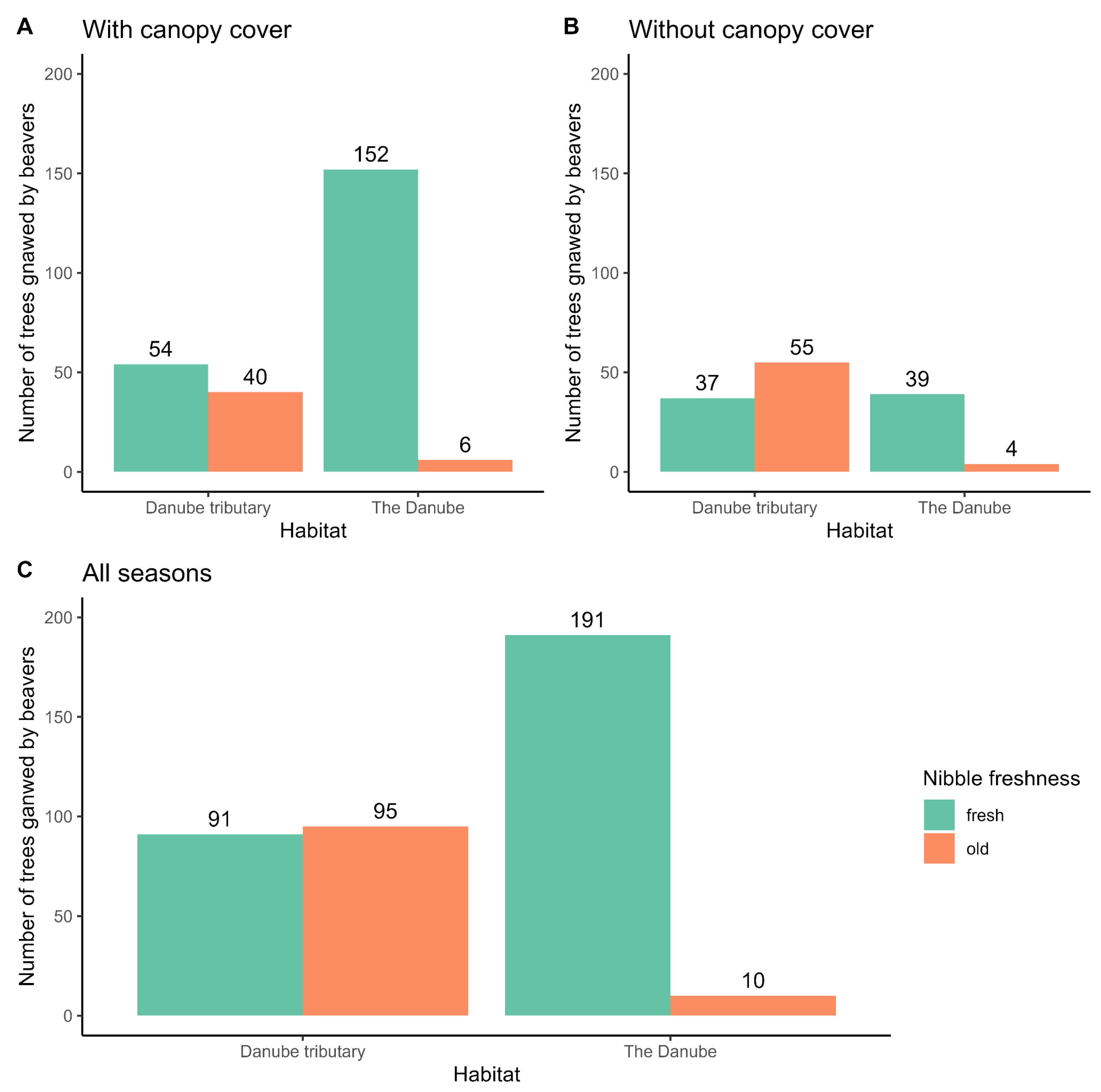

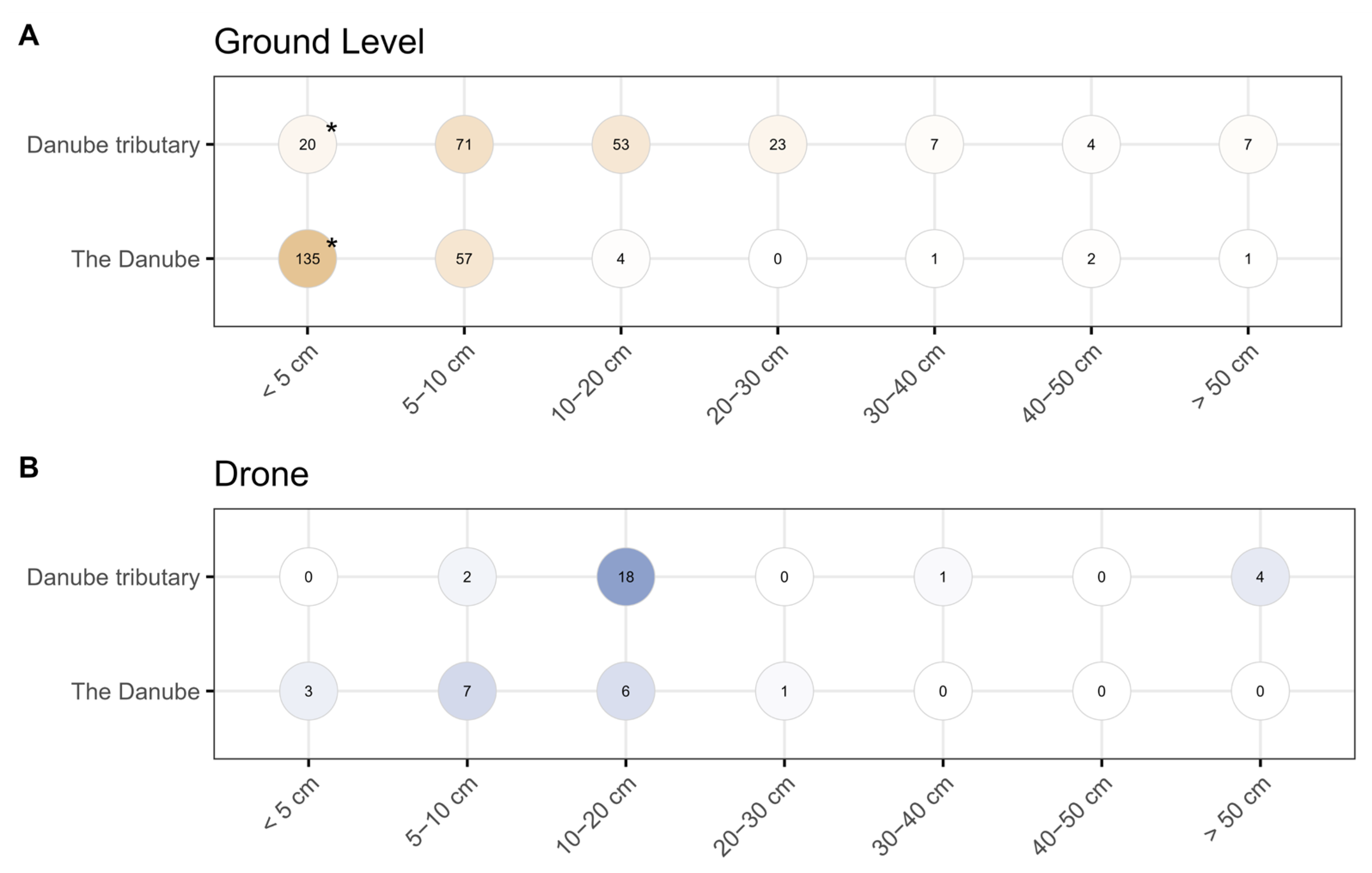

3.1. Signs of Beaver Activity

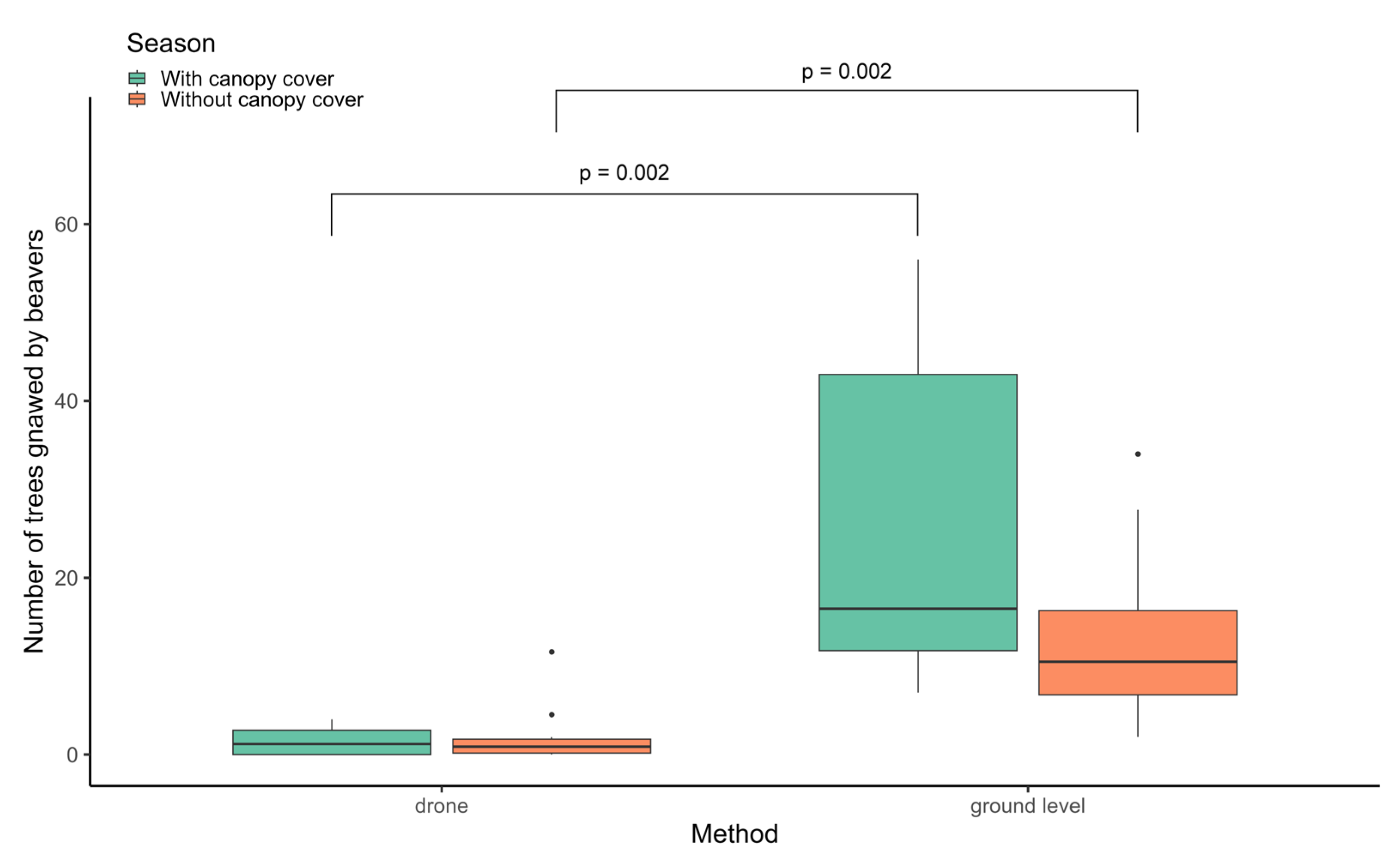

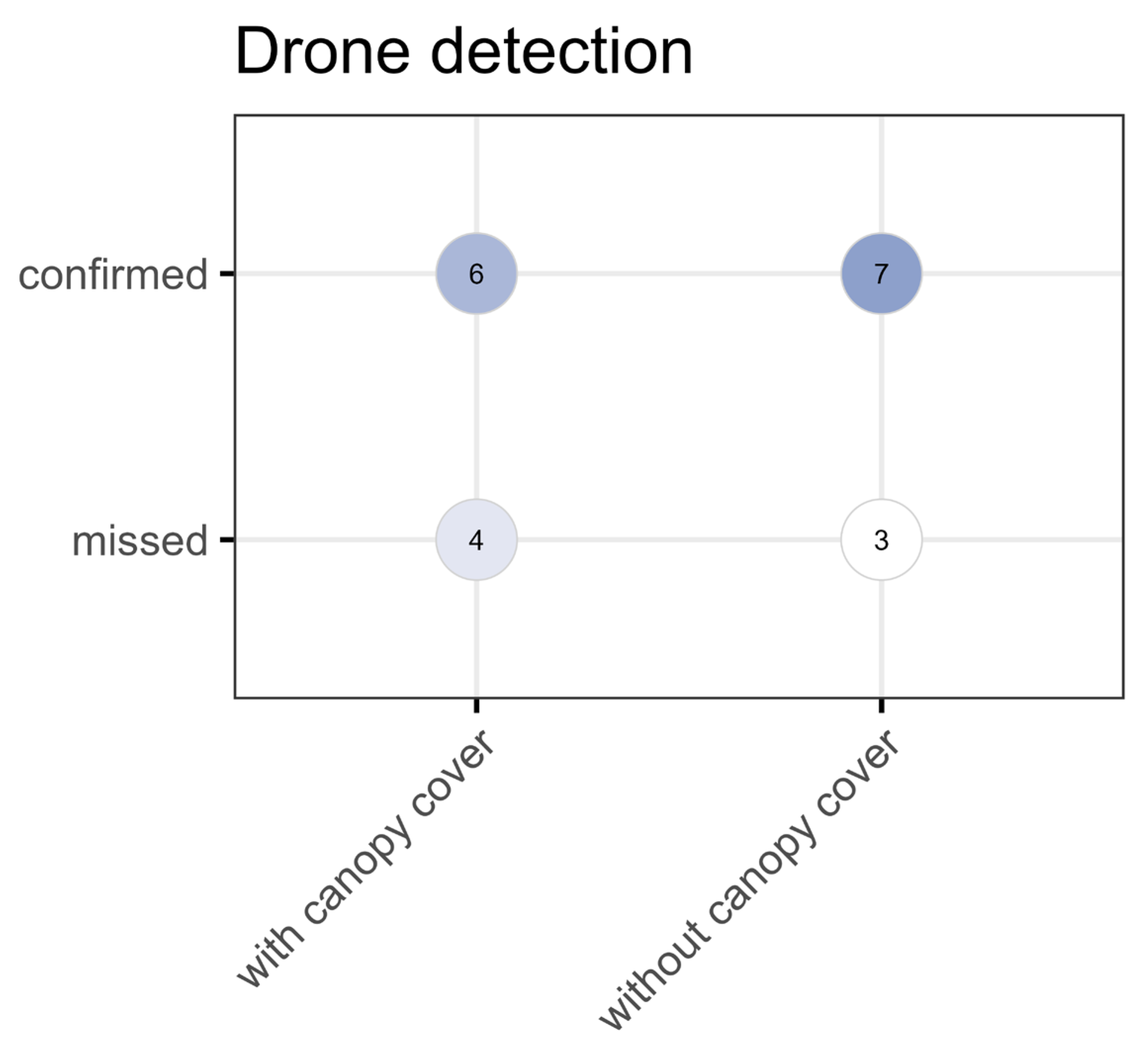

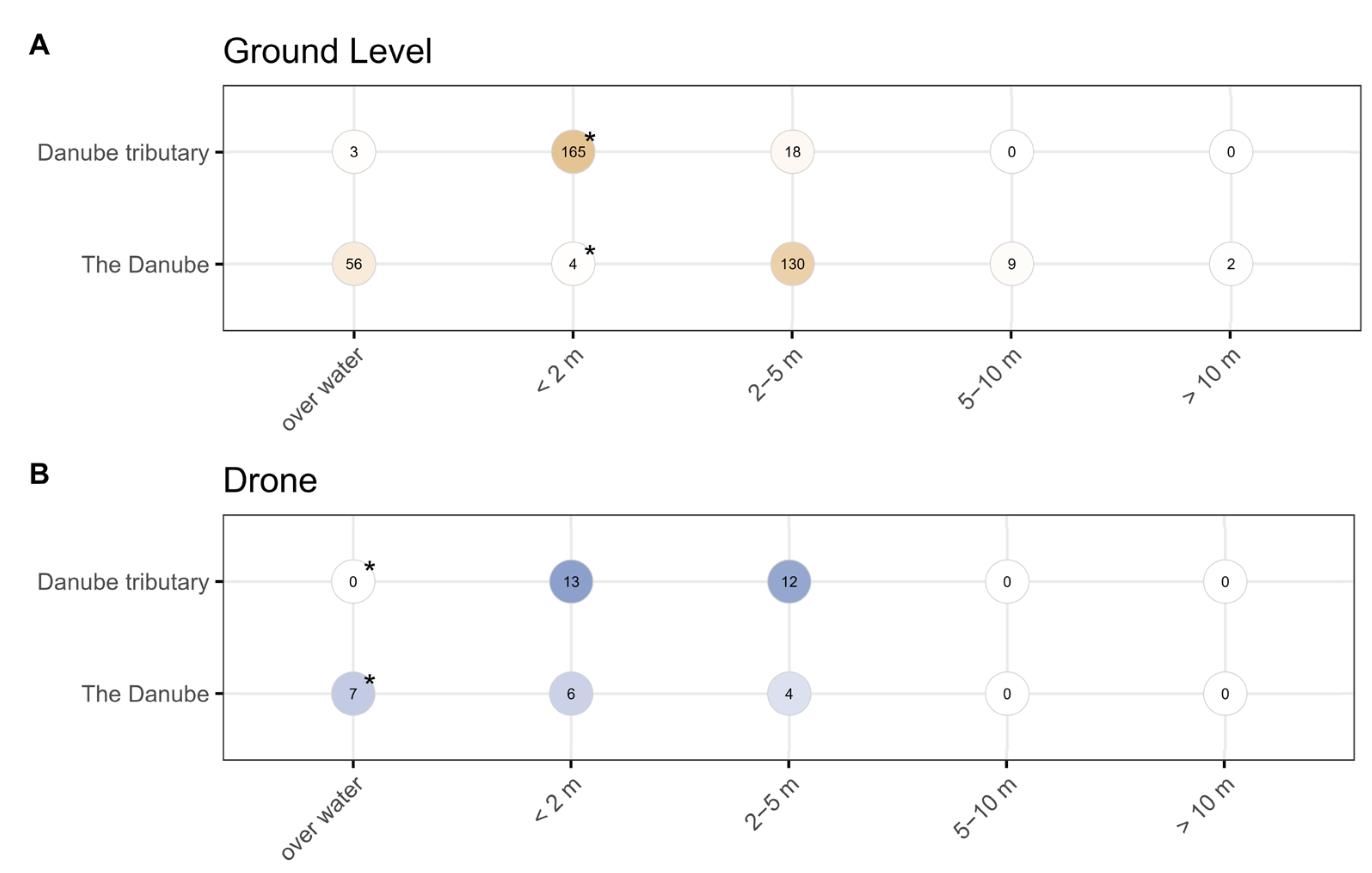

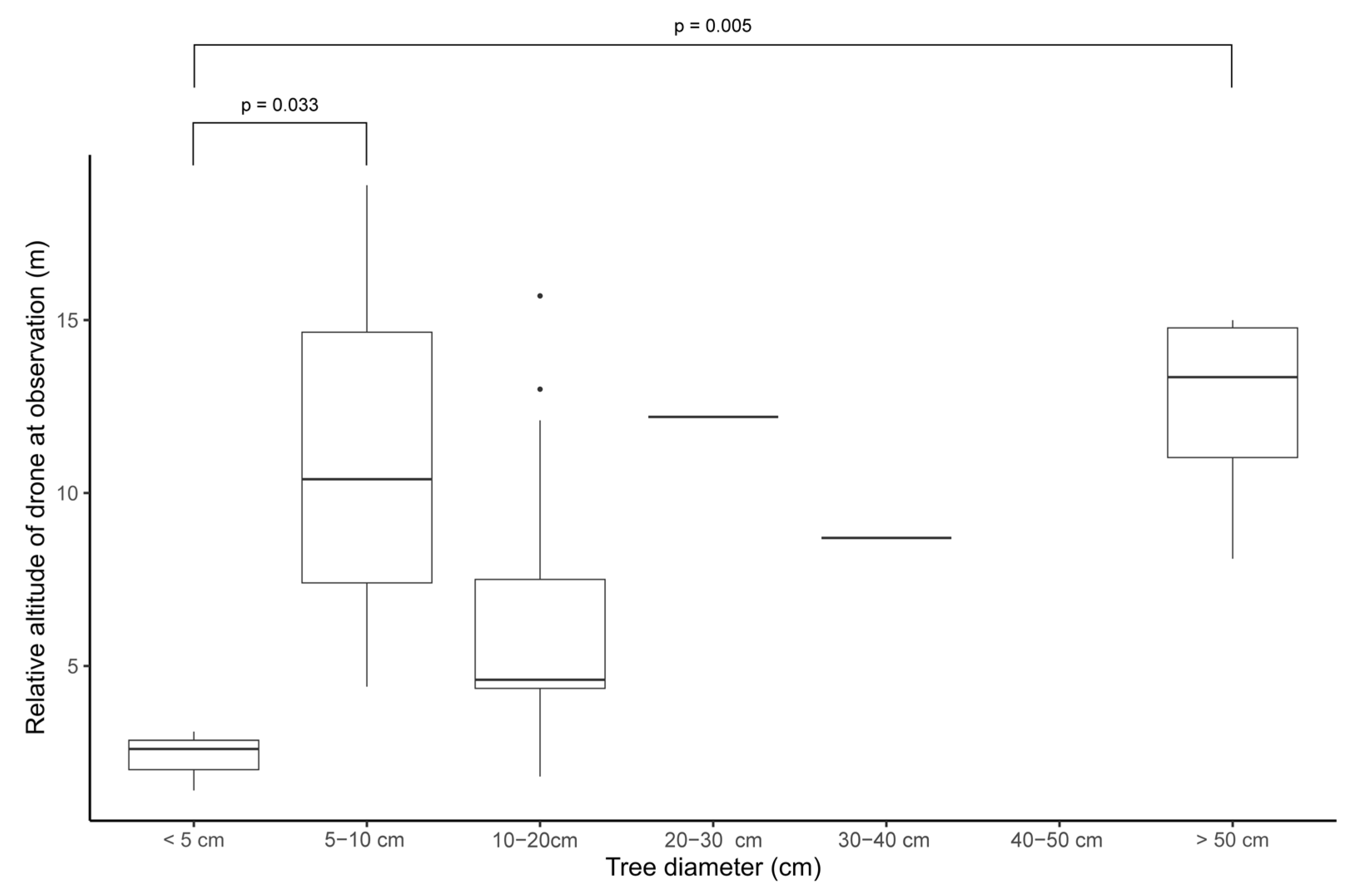

3.2. Method Application and Comparison

4. Discussion

4.1. Signs of Beaver Activity

4.2. Methods Application and Comparison

5. Conclusions and Directions for Future Improvement

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dewas, M.; Herr, J.; Schley, L.; Angst, C.; Manet, B.; Landry, P.; Catusse, M. Recovery and Status of Native and Introduced Beavers Castor fiber and Castor Canadensis in France and Neighbouring Countries: Status of Beavers in Western Continental Europe. Mamm. Rev. 2012, 42, 144–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boev, Z.; Spassov, N. Past Distribution of Castor fiber in Bulgaria: Fossil, Subfossil and Historical Records (Rodentia: Castoridae). Lynx 2019, 50, 37–49. [Google Scholar]

- Chipev, N.; Beron, P.; Biserkov, V. Red Data Book of the Republic of Bulgaria. Volume II: Animals; Golemansky, V., Peev, D., Chipev, N., Beron, P., Biserkov, V., Eds.; Bulgarian Academy of Sciences and Ministry of Environment and Water: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Frosch, C.; Kraus, R.H.S.; Angst, C.; Allgöwer, R.; Michaux, J.; Teubner, J.; Nowak, C. The Genetic Legacy of Multiple Beaver Reintroductions in Central Europe. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e97619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, S.; Weinhardt, M.; Allgöwer, R.; Merker, S. Recolonizing Lost Habitat—How European Beavers (Castor fiber) Return to South-Western Germany. Mamm. Res. 2018, 63, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanaki, A.; Kominos, T.; Youlatos, D.; Campbell-Palmer, R.; Schwab, G.; Puttock, A.; Gow, D.; Politis, G.; Jones, N.; Dimitrakopoulos, P.; et al. Preparatory Actions for the Reintroduction of the Eurasian Beaver Castor fiber in Greece. In Proceedings of the 9th International Beaver Symposium (9IBS), Brașov, Romania, 18–22 September 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ionescu, G.; Ionescu, O.; Jurj, R.; Paşca, C.; Popa, M.; Popescu, I.; Sârbu, G.; Scurtu, M.; Vişan, D. Castorul în România. Monografie; Editura Silvică: Bucharest, Romania, 2010; ISBN 978-606-8020-09-9. [Google Scholar]

- Kiss, J.; Vasile, A.; Bozagievici, R.; Dorosencu, A.; Marinov, M. Considerations Regarding the Occurrence of the Eurasian Beaver (Castor fiber Linnaeus 1758) in the Danube Delta (Romania). Sci. Ann. Danub. Delta Inst. 2012, 18, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouroș, G.; Paladi, V.; Cassir, P. First Report of Eurasian Beaver (Castor fiber Linnaeus 1758) in Republic of Moldova. North West. J. Zool. 2021, 18, e211701. Available online: http://biozoojournals.ro/nwjz/index.html (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Kodzhabashev, N.D.; Tsvyatkova, D.D.; Krastev, K.V.; Ignatov, M.M.; Teofilova, T.M. The Eurasian Beaver Castor fiber Linnaeus, 1758 (Rodentia: Castoridae) Is Returning to Bulgaria. Acta Zool. Bulg. 2021, 73, 587–595. [Google Scholar]

- Natchev, N.D.; Nedyalkov, N.P.; Kaschieva, M.Z.; Koynova, T.V. They Are Back: Notes on the Presence and the Life Activities of the Eurasian Beaver (Castor fiber L. 1758) from the Territory of Bulgaria. Ecol. Balk. 2021, 13, 179. [Google Scholar]

- Bobeva, A.; Nikova, P.; Borissov, S.; Koshev, Y.; Todorov, V.; Dimitrova, B.; Ignatov, M.; Rolečková, B.; Uhlíková, J.; Kachamakova, M. Recolonisation or Invasion? First Insights into the Origin of the Newly Established Beaver Populations in Bulgaria Using eDNA. J. Vert. Biol. 2025, 74, 24199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, H.; Puttock, A.; Wheaton, J.M.; Macfarlane, W.; Elliott, M.; Anderson, K.; Brazier, R.E. Predicting the Expansion and Impact of the Eurasian Beaver (Castor fiber) at Catchment Scales. In Proceedings of the EGU General Assembly Conference Abstracts, Vienna, Austria, 8–13 April 2018; Volume 20, p. 782. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, J.P.; Jones, C.G.; Flecker, A.S. An Ecosystem Engineer, the Beaver, Increases Species Richness at the Landscape Scale. Oecologia 2002, 132, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciechanowski, M.; Kubic, W.; Rynkiewicz, A.; Zwolicki, A. Reintroduction of Beavers Castor fiber May Improve Habitat Quality for Vespertilionid Bats Foraging in Small River Valleys. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2011, 57, 737–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosell, F.; Lodberg-Holm, H.K.; Meijer, F.; Midbøe, M. A Home for the Many? Beaver Lodges as Hotspots for Bird and Mammal Diversity. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 990, 179898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BISE European Beaver—Castor fiber. Available online: https://biodiversity.europa.eu/species/1377 (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Hart, J.; Rubinato, M.; Lavers, T. An Experimental Investigation of the Hydraulics and Pollutant Dispersion Characteristics of a Model Beaver Dam. Water 2020, 12, 2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macfarlane, W.W.; Wheaton, J.M.; Bouwes, N.; Jensen, M.L.; Gilbert, J.T.; Hough-Snee, N.; Shivik, J.A. Modeling the Capacity of Riverscapes to Support Beaver Dams. Geomorphology 2017, 277, 72–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arismendi, I.; Penaluna, B.E.; Jara, C.G. Introduced Beaver Improve Growth of Non-Native Trout in Tierra Del Fuego, South America. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 10, 9454–9465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leary, R.J. Landscape and Habitat Attributes Influencing Beaver Distribution; Utah State University: Logan, UT, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Havens, R.P.; Crawford, J.C.; Nelson, T.A. Survival, Home Range, and Colony Reproduction of Beavers in East-Central Illinois, an Agricultural Landscape. Amer. Midl. Nat. 2013, 169, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swank, W.G.; Glover, F.A. Beaver Censusing by Airplane. J. Wildl. Manag. 1948, 12, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, N.F. Accuracy of Aerial Censusing for Beaver Colonies in Newfoundland. J. Wildl. Manag. 1981, 45, 1014–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swenson, J.E.; Knapp, S.J.; Martin, P.R.; Hinz, T.C. Reliability of Aerial Cache Surveys to Monitor Beaver Population Trends on Prairie Rivers in Montana. J. Wildl. Manag. 1983, 47, 697–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diez, Y.; Kentsch, S.; Fukuda, M.; Caceres, M.L.; Moritake, K.; Cabezas, M. Deep Learning in Forestry Using UAV-Acquired RGB Data: A Practical Review. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 2837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gedeon, C.I.; Árvai, M.; Szatmári, G.; Brevik, E.C.; Takáts, T.; Kovács, Z.A.; Mészáros, J. Identification and Counting of European Souslik Burrows from UAV Images by Pixel-Based Image Analysis and Random Forest Classification: A Simple, Semi-Automated, yet Accurate Method for Estimating Population Size. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgson, J.C.; Mott, R.; Baylis, S.M.; Pham, T.T.; Wotherspoon, S.; Kilpatrick, A.D.; Raja Segaran, R.; Reid, I.; Terauds, A.; Koh, L.P. Drones Count Wildlife More Accurately and Precisely than Humans. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2018, 9, 1160–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puttock, A.K.; Cunliffe, A.M.; Anderson, K.; Brazier, R.E. Aerial Photography Collected with a Multirotor Drone Reveals Impact of Eurasian Beaver Reintroduction on Ecosystem Structure. J. Unmanned Veh. Syst. 2015, 3, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, B.M.; Tape, K.D.; Clark, J.A.; Bondurant, A.C.; Ward Jones, M.K.; Gaglioti, B.V.; Elder, C.D.; Witharana, C.; Miller, C.E. Multi-Dimensional Remote Sensing Analysis Documents Beaver-Induced Permafrost Degradation, Seward Peninsula, Alaska. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawathe, S.P.; Saffaf, R.; Garbagna, L.; Saheer, L.B.; Oghaz, M.M.; Wheeler, H.C. Beaver Habitat Terrain Identification Using Aerial Imagery. In Proceedings of the Ninth International Congress on Information and Communication Technology, London, UK, 19–22 February 2024; Yang, X.-S., Sherratt, S., Dey, N., Joshi, A., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 105–118. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, I.; Deleva, S. Going Against the Flow: Notes on the Re-Colonisation of the Eurasian Beaver Castor fiber Linnaeus, 1758 in Northern Bulgaria. ZooNotes 2025, 266, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinova, P.; Chernikov, C.; Petkov, N.; Nedyalkov, N.; Natchev, N. They Are Heading South -New Data from the Distribution of the Eurasian Beaver (Castor fiber) in Bulgaria. ZooNotes 2025, 265, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosell, F.; Campbell-Palmer, R. Beavers: Ecology, Behaviour, Conservation, and Management; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2021; ISBN 978-0-19-187286-0. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, D.A.; Setiawan, Y. Possibility of Applying Unmanned Aerial Vehicle and Thermal Imaging in Several Canopy Cover Class for Wildlife Monitoring—Preliminary Results. In Proceedings of the E3S Web of Conferences, Online, 23–25 November 2020; Volume 211. [Google Scholar]

- Hvala, A.; Rogers, R.M.; Alazab, M.; Campbell, H.A. Supplementing Aerial Drone Surveys with Biotelemetry Data Validates Wildlife Detection Probabilities. Front. Conserv. Sci. 2023, 4, 1203736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Executive Agency for Exploration and Maintenance of the Danube River Water Level in the Bulgarian section of the Danube River. Available online: https://www.appd-bg.org/ (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Trentanovi, G.; Viviano, A.; Mazza, G.; Busignani, L.; Magherini, E.; Giovannelli, A.; Traversi, M.L.; Mori, E. Riparian Forests Throwback at the Eurasian Beaver Era: A Woody Vegetation Assessment for Mediterranean Regions. Biodivers. Conserv. 2023, 32, 4259–4274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iason, G.R.; Sim, D.A.; Brewer, M.J.; Moore, B.D. The Scottish Beaver Trial: Woodland Monitoring 2009–2013, Final Report; Scottish Natural Heritage: Inverness, UK, 2014; p. 82. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, P. European Beaver and Woodland Habitats: A Review; Scottish Natural Heritage: Inverness, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Vorel, A.; Válková, L.; Hamšíková, L.; Maloň, J.; Korbelová, J. Beaver Foraging Behaviour: Seasonal Foraging Specialization by a Choosy Generalist Herbivore. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2015, 69, 1221–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misiukiewicz, W.; Gruszczynska, J.; Grzegrzółka, B.; Januszewicz, M. Impact of the European Beaver (Castor fiber L.) Population on the Woody Vegetation of Wigry National Park. Rocz. Nauk. Pol. Tow. Zootech. 2016, 12, 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackowiak, M.; Busher, P.; Krauze-Gryz, D. Eurasian Beaver (Castor fiber) Winter Foraging Preferences in Northern Poland—The Role of Woody Vegetation Composition and Anthropopression Level. Animals 2020, 10, 1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preti, F.; Saracino, R.; Signorile, A.V.; Dani, A.; Pucci, C.; Rillo Migliorini Giovannini, M. Beavers as Water Bioengineers: Effects on the Bank Roughness in the Early Years of New Settlement in Tuscany. J. Ecohydraul. 2025, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider-Binder, E. Floodplain Forests along the Lower Danube. Transylv. Rev. Syst. Ecol. Res. 2009, 8, 113–136. [Google Scholar]

- Vera-Amaro, R.; Rivero-Ángeles, M.E.; Luviano-Juárez, A. Data Collection Schemes for Animal Monitoring Using WSNs-Assisted by UAVs: WSNs-Oriented or UAV-Oriented. Sensors 2020, 20, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunton, E.; Bolin, J.; Leon, J.; Burnett, S. Fright or Flight? Behavioural Responses of Kangaroos to Drone-Based Monitoring. Drones 2019, 3, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitsche, K.-A. Behaviour of Beavers (Castor fiber albicus Matschie, 1907) during the Flood Periods. In Proceedings of the 2nd European Beaver Symposium, Białowieża, Poland, 27–30 September 2000; Carpathian Heritage Society: Białowieża, Poland, 2000; pp. 85–90. [Google Scholar]

- Kurstjens, G.; Bekhuis, J. Adaptation of Beavers (Castor fiber) to Extreme Water Level Fluctuations and Ecological Implications. Lutra 2004, 46, 147–151. [Google Scholar]

- Fairfax, E.; Zhu, E.; Clinton, N.; Maiman, S.; Shaikh, A.; Macfarlane, W.W.; Wheaton, J.M.; Ackerstein, D.; Corwin, E. EEAGER: A Neural Network Model for Finding Beaver Complexes in Satellite and Aerial Imagery. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2023, 128, e2022JG007196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askam, E.; Nagisetty, R.M.; Crowley, J.; Bobst, A.L.; Shaw, G.; Fortune, J. Satellite and sUAS Multispectral Remote Sensing Analysis of Vegetation Response to Beaver Mimicry Restoration on Blacktail Creek, Southwest Montana. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 6199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kachamakova, M.; Nikova, P.K.; Todorov, V.; Zheleva, B.; Koshev, Y. Characteristics of Beaver Activity in Bulgaria and Testing of a UAV-Based Method for Its Detection. Conservation 2025, 5, 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/conservation5040074

Kachamakova M, Nikova PK, Todorov V, Zheleva B, Koshev Y. Characteristics of Beaver Activity in Bulgaria and Testing of a UAV-Based Method for Its Detection. Conservation. 2025; 5(4):74. https://doi.org/10.3390/conservation5040074

Chicago/Turabian StyleKachamakova, Maria, Polina K. Nikova, Vladimir Todorov, Blagovesta Zheleva, and Yordan Koshev. 2025. "Characteristics of Beaver Activity in Bulgaria and Testing of a UAV-Based Method for Its Detection" Conservation 5, no. 4: 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/conservation5040074

APA StyleKachamakova, M., Nikova, P. K., Todorov, V., Zheleva, B., & Koshev, Y. (2025). Characteristics of Beaver Activity in Bulgaria and Testing of a UAV-Based Method for Its Detection. Conservation, 5(4), 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/conservation5040074