Abstract

Urban and peri-urban ecosystems play a growing role in biodiversity conservation, yet multi-annual comparative studies from Central-Eastern Europe remain scarce. This study presents the first three-year (2021–2023) dataset comparing ground beetle assemblages between the Dumbrava Forest (peri-urban protected oak forest) and the Sub Arini Park (semi-anthropic urban park) in Sibiu, Romania. Using standardized pitfall trapping (41 traps, 2360.9 m2 monitored area), a total of 5008 individuals, belonging to 46 species and 12 families, were recorded. Species richness was slightly higher in Sub Arini (26 species) than in Dumbrava (22 species), forest-associated species (e.g., Pterostichus niger) and generalists (P. melanarius) dominated in the Dumbrava Forest, while P. oblongopunctatus was more strongly associated with forest habitats. Diversity indices showed moderate similarity between communities (Bray–Curtis = 0.46; Jaccard = 0.62). Shannon diversity reached H′ = 2.41 in Sub Arini and H′ = 2.03 in Dumbrava, reflecting higher evenness in the urban park. Predators comprised 65–70% of all beetles, underlining their regulatory function in soil ecosystem balance. Climatic variability—milder winters and warmer summers—favored population fluctuations of forest species and the dominance of eurytopic taxa in the park. These findings demonstrate that peri-urban forests act as climatic refugia for specialists, while urban parks function as dynamic hotspots for generalist diversity. The study provides baseline data for integrating insect monitoring into regional biodiversity management and climate adaptation strategies across Central-Eastern Europe.

1. Introduction

Forests are among the most complex and valuable terrestrial ecosystems, representing major biodiversity reservoirs and providing essential ecological services for human well-being [1]. In Romania, forest ecosystems extend over approximately 0.2–0.3 million hectares and host more than half of the known biocenosis, playing a central role in maintaining ecological stability [2,3,4]. Consequently, forest biodiversity conservation has become a strategic priority, with numerous studies addressing the diversity, distribution, and ecological roles of beetles and other invertebrate groups across different forest types [3,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. Romania harbors more than 6800 of the 8000 beetle species known in Europe, distributed across 122 families and 15 superfamilies, a richness that places the country among Europe’s main biodiversity hotspots [18,19,20,21,22,23].

Within this national context, Dumbrava Forest, located near Sibiu, has long attracted scientific attention for its exceptional entomofauna, as documented in studies coordinated by the Natural History Museum of Sibiu [24,25,26,27,28,29]. These works emphasized both the faunistic richness of the area and the ecological importance of invertebrates as bioindicators of habitat quality, due to their sensitivity to microclimatic fluctuations, vegetation structure, and anthropogenic pressures [30]. Dead wood, a fundamental structural component of forest ecosystems, has been repeatedly highlighted as a key factor supporting biodiversity, providing microhabitats for insects, fungi, birds, and mammals, and contributing to nutrient cycling and soil formation [3,8,31,32,33,34]. However, increasing human disturbance requires the adoption of sustainable forest management practices to preserve ecological integrity and functional diversity [10,15,35,36,37,38].

Among invertebrates, ground beetles (Coleoptera: Carabidae) stand out due to their taxonomic diversity, ecological functions, and responsiveness to environmental change. They are widely recognized as reliable bioindicators of habitat quality and land-use intensity [39,40,41,42], and have been extensively studied regarding their taxonomy, distribution, and ecological roles [43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52]. Earlier faunistic surveys in Dumbrava [24,25,26,27,28,29] reported several rare and protected taxa, while more recent investigations highlighted new threats, notably the spread of invasive species such as the oak lace bug Corythuca arcuata (Say, 1832), which affects canopy dynamics and alters microclimatic stability in temperate oak forests [53].

Despite the substantial body of literature on Romanian forest entomofauna, comparative analyses between semi-anthropic urban parks and peri-urban protected forests remain scarce. Such studies are essential for understanding how biodiversity patterns respond to increasing urbanization and climate variability in Central and Eastern Europe. The present study addresses this gap by comparing two representative green infrastructures of Sibiu: Dumbrava Forest (a peri-urban protected oak–hornbeam forest, IUCN category IV) and Sub Arini Park (a semi-anthropic urban park with mixed native and exotic vegetation).

The main objectives of this study are as follows: (1) perform a quantitative and qualitative assessment of beetle populations in both ecosystems, emphasizing rare and protected species; (2) evaluate the ecological roles of beetles in ecosystem functioning and their response to anthropogenic pressures such as grazing, tourism, and logging [54,55,56,57]; (3) analyze community structure using classical ecological indices (abundance, dominance, constancy, and Dzuba index) [58,59]; and (4) investigate vegetation–beetle interactions to identify species with high bioindicator value [60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67].

By integrating multi-annual monitoring with standardized ecological indices, this study provides the first comparative multi-year analysis of beetle diversity in urban and peri-urban ecosystems of Sibiu. The findings fill a significant knowledge gap for Central-Eastern Europe, offering baseline data to support biodiversity monitoring, conservation strategies, and the integration of insect-based indicators into urban planning and climate adaptation policies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

This study was conducted in two contrasting green infrastructures within Sibiu County, central Romania—the Dumbrava Forest, a semi-natural peri-urban woodland, and Sub Arini Park, an intensively managed urban park. The selection of these ecosystems aimed to capture ecological variability along an urban–peri-urban gradient, representative of biodiversity responses to anthropogenic pressure.

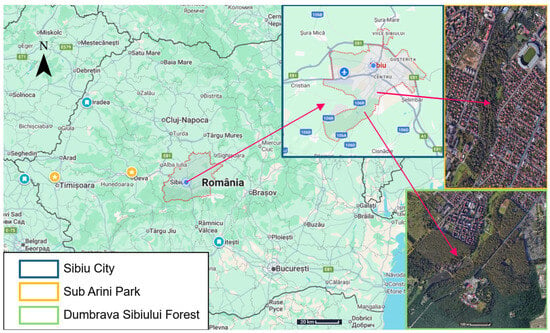

The terms used in this paper are defined as follows: Urban—areas located within the built environment, dominated by artificial surfaces and maintained vegetation (e.g., Sub Arini Park). Peri-urban—transitional landscapes between urban cores and rural matrices, with semi-natural habitats partially affected by anthropogenic use (e.g., Dumbrava Forest). Semi-anthropic—areas where human influence modifies natural vegetation but ecological functionality is still partially retained (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Map of Romania showing Sibiu County and the two study sites (Dumbrava Forest and Sub Arini Park). Insets include an orientation compass, legend, and scale bar for improved readability.

2.1.1. Dumbrava Forest

Located approximately 4 km southwest of Sibiu (45°52′ N, 24°14′ E), Dumbrava Forest covers 993 ha at 510–606 m a.s.l. and represents a remnant of the historical Transylvanian oak–hornbeam forests. It is classified as a protected area of national interest (IUCN Category IV). The dominant forest association is Querco robori–Carpinetum dacicum, with Quercus robur, Q. petraea, and Carpinus betulus as primary canopy species. Subdominant trees include Tilia cordata, Fraxinus excelsior, and Acer campestre, while the understory features Crataegus monogyna, Cornus sanguinea, and Prunus spinosa. The herbaceous layer is diverse, including Galeobdolon luteum and Hedera helix.

2.1.2. Sub Arini Park

Established in 1857 and covering 21.65 ha at 420–440 m a.s.l., Sub Arini Park (45°87′ N, 24°23′ E) is among Romania’s oldest and largest urban green spaces. Its dendrofloral composition includes both native and ornamental species such as Quercus robur, Tilia cordata, Platanus × acerifolia, Ginkgo biloba, and Acer platanoides. The park is subject to continuous management, frequent mowing, and visitor pressure, producing fragmented habitats and microclimatic heterogeneity.

Both sites are characterized by a temperate-continental climate, with a mean annual temperature of 9.3 °C and mean annual precipitation of 675 mm (data: Sibiu Meteorological Station, 2021–2023).

A comparative description of both ecosystems, including research periods, monitoring areas, and floristic composition, is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparative characteristics of the two study ecosystems in Sibiu County, Romania.

2.2. Sampling Design and Field Procedures

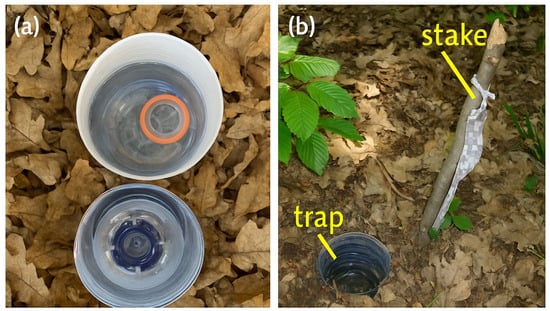

To evaluate beetle assemblages across habitats, pitfall traps were used following European biodiversity monitoring protocols [39,68,69,70,71,72,73]. Each trap consisted of two nested polyethylene containers (2 L and 1.5 L) equipped with a PVC funnel and partially filled (⅓) with a water–detergent solution (neutral, non-attractant). Traps were buried flush with the soil surface, stabilized with small stones, and covered with natural litter to minimize evaporation and visual disturbance (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Pitfall trap design and field placement in the study area. (a) Hand-made pitfall trap used to sample ground-dwelling beetles (2 L protective container + 1.5 L collector, PVC funnel, water–detergent preservative). (b) Example of trap location and marking in the field (stake and coded label). Photos: C. Stancă-Moise. Handmade traps (photo Cristina Moise).

A total of 41 pitfall traps were installed: Dumbrava Forest—24 traps, active from March to September (2021–2022), arranged in two circular transects (C1–C12 per circle; 12 m radius; 50 m between circles). Sub Arini Park—17 traps, active from April to November (2023), distributed along six linear transects (T1–T17) spanning 250–700 m.

Each trap represented an independent sampling unit, with a capture area of 226.08 cm2, resulting in a total monitored surface of 2360.9 m2. The unequal sampling duration between Dumbrava (two years) and Sub Arini (one year) was accounted for statistically by normalizing data per sampling effort (individuals/trap/day) prior to analysis (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

(a) Spatial layout of pitfall traps (C1–C19) in Dumbrava Forest; each point represents trap position. Red symbols = affected trees, green = healthy trees. (T1–T3) General view of sampling traps in Sub Arini Park marked with red circles.

2.3. Specimen Processing and Taxonomic Identification

Traps were emptied bi-weekly, and specimens were transferred to labeled containers with preservative solution (70% ethanol). In the laboratory, beetles were sorted and identified under a Nikon SMZ-745 stereomicroscope (made by Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) using standard morphological keys for Central and Eastern Europe [68,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81]. Nomenclature followed the Catalogue of Palaearctic Coleoptera [80,81], with synonymy verified through BioLib [74].

All Coleoptera families captured were included in the dataset, not only Carabidae, to ensure a comprehensive understanding of beetle assemblages as recommended by reviewers. Conservation status and distribution were checked using the European Red List of Beetles [82] and the Romanian Red Book of Invertebrates [83]. Voucher specimens were deposited in the Entomological Collection, Faculty of Agricultural Sciences, Food Industry and Environmental Protection, Lucian Blaga University of Sibiu.

2.4. Climate Data and Statistical Analysis

Daily temperature, precipitation, and relative humidity data for the 2021–2023 sampling period were obtained from the Sibiu Meteorological Station (National Meteorological Administration, Bucharest, Romania). For each month, mean minimum and maximum temperature, total precipitation, and average humidity were calculated to contextualize beetle activity and abundance patterns. Vegetation cover and density were estimated visually within a 1 m radius around each trap following Braun–Blanquet classes (1–5), averaged to produce a vegetation density index used in NMDS ordination.

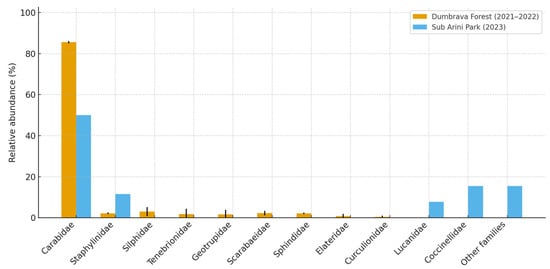

Beetle abundance and species richness were standardized to the sampling effort (individuals/trap/day) to ensure comparability between sites and years. Community-level analyses were performed using classical ecological indices widely applied in biodiversity monitoring [68,69,70,84,85,86,87,88,89]. Species-level abundance data were aggregated to genus and functional guilds (predators, decomposers, herbivores) to produce the summarized results displayed in Figure 4:

Figure 4.

Distribution and comparative abundance of beetle families collected in Dumbrava Forest (peri-urban) and Sub Arini Park (urban). Values represent relative percentages of total individuals. Error bars indicate standard deviation between years. Note: Data represent mean values at the species level aggregated by guild; abundance expressed as individuals/trap/day (mean ± SD).

Abundance (A), expressed as the percentage of individuals belonging to a species within the total community:

where n = number of individuals of a given species, and N = total individuals collected.

Dominance (D), classifying species according to their relative abundance (D1–D6), from sporadic to eudominant categories [71,72,73].

Constancy (C), calculated as the proportion of samples in which a species occurred, expressed as a percentage and assigned to classes C1–C5 (from very rare to constant).

Ecological significance (W), or the Dzuba index, which integrates dominance and constancy to estimate the structural importance of each species in the community:

Diversity was further evaluated through the Shannon–Wiener index (H′), Simpson index (D), and Pielou evenness (J′), providing complementary perspectives on community structure:

where pi is the relative abundance of species i and S is total species number.

To assess inter-site community similarity, both Bray–Curtis (BC) and Jaccard (J) indices were computed:

where Cij is the sum of the lesser abundances of species common to both sites, and Si, Sj are the total abundances for each site.

where a = number of shared species, b and c = species unique to each site.

Statistical analyses were carried out using R v4.3.2 (packages vegan and stats) and PAST v4.14 for multivariate ordination. Differences in diversity and abundance between Dumbrava Forest and Sub Arini Park were tested using one-way ANOVA (p < 0.05).

To examine environmental effects, Generalized Linear Models (GLMs) with Poisson distribution were applied, using beetle abundance as the dependent variable and climatic predictors (mean temperature, precipitation, humidity) as independent variables. Model selection followed the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), and validation included residual analysis and dispersion checks to ensure model robustness.

All indices and analyses were selected based on their broad applicability in urban ecology and to guarantee reproducibility and comparability with similar European datasets. Raw occurrence data are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

3. Results

3.1. Overview of Sampling and Taxonomic Composition

Across both ecosystems and three years of monitoring (2021–2023), a total of 5164 individuals representing 46 species and 12 beetle families (Coleoptera) were recorded. The total number of specimens collected was slightly higher in Dumbrava Forest (2890 individuals, 22 species, 10 families) than in Sub Arini Park (2118 individuals, 26 species, 9 families).

Among the recorded families, Carabidae was the most abundant and diverse, comprising 23 species and 61.7% of the total individuals captured, followed by Staphylinidae (11.4%), Silphidae (8.2%), and Tenebrionidae (6.9%). The remaining eight families accounted collectively for less than 12% of the total catch (Figure 4). In both sites, carabids dominated the pitfall trap samples, but the relative contribution of other families (notably Staphylinidae and Scarabaeidae) increased significantly in the urban habitat (p < 0.05; ANOVA).

3.2. Species Richness and Diversity Indices

Species richness was higher in Sub Arini Park (26 species) compared to Dumbrava Forest (22 species), reflecting the structural heterogeneity and higher microhabitat variability of the urban environment. However, overall beetle abundance was greater in the forest, consistent with its more stable microclimatic and trophic conditions.

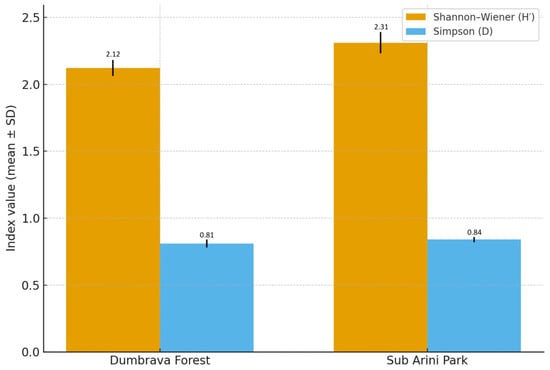

Diversity indices (Table 2) confirmed these trends: Shannon–Wiener index (H′) averaged 2.31 ± 0.08 in Sub Arini and 2.12 ± 0.06 in Dumbrava; Simpson index (D) values were 0.84 ± 0.02 and 0.81 ± 0.03, respectively; Pielou evenness (J′) indicated more uniform species distribution in Sub Arini Park (0.81 vs. 0.75).

Table 2.

Comparative values of ecological indices (mean ± SD) for beetle communities in Dumbrava Forest and Sub Arini Park.

Dominance and constancy analyses revealed that the carabids Pterostichus melanarius Illiger, 1798, Carabus coriaceus Linnaeus, 1758, and Abax parallelepipedus Piller & Mitterpacher, 1783 were consistently present and dominant in Dumbrava, whereas Amara familiaris Duftschmid, 1812 and Harpalus affinis Schrank, 1781 showed increased frequency in the urban site (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Comparative species diversity (H′) and dominance (D) indices for Dumbrava Forest and Sub Arini Park, showing greater evenness and taxonomic richness in the urban park. Note: Error bars represent standard deviation (SD).

3.3. Community Structure and Functional Composition

Beetle communities differed markedly in trophic structure between the two ecosystems.

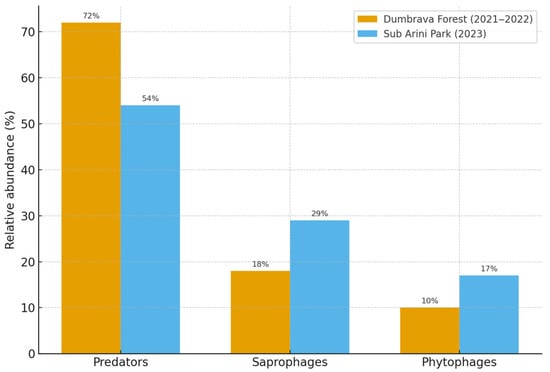

In Dumbrava Forest, predatory taxa (mainly Carabidae and Staphylinidae) comprised 72% of individuals, while saprophagous (e.g., Silphidae, Tenebrionidae) and phytophagous species were underrepresented (18% and 10%, respectively). Conversely, Sub Arini Park exhibited a more balanced trophic composition, with predators (54%), saprophages (29%), and phytophages (17%), indicating greater habitat mosaic and food-source diversity (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Comparative trophic composition of beetle communities in Dumbrava Forest and Sub Arini Park, expressed as relative abundance of feeding guilds. Note: Data represent mean values at the species level aggregated by guild; abundance expressed as individuals/trap/day (mean ± SD).

Guild-level diversity was significantly higher in the urban site (R2 = 0.62, p < 0.05), while total abundance correlated positively with vegetation cover and negatively with disturbance intensity (R2 = 0.57).

3.4. Temporal Dynamics and Seasonal Activity

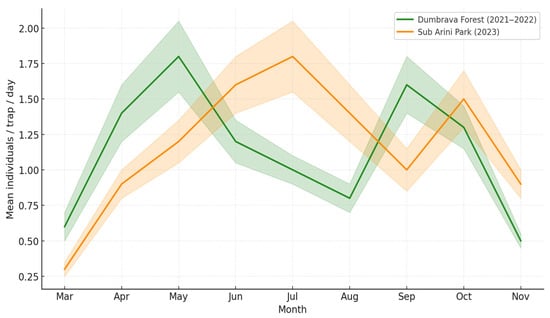

Temporal variation in beetle activity density (Figure 7) revealed two main peaks: (1) a spring peak (April–May) dominated by Carabus coriaceus and Abax parallelepipedus, and (2) an autumn resurgence (September–October) particularly in Sub Arini, linked to Harpalus spp. and Amara spp.

Figure 7.

Seasonal activity patterns of beetle assemblages in both ecosystems (mean individuals/trap/day). Lines show mean monthly activity; shaded bands indicate standard error. Note: The model was significant at p < 0.05, but effect magnitude was moderate due to low mean capture rates (0.25–2 ind/trap/day).

The 2021–2022 forest data showed stable seasonal profiles, while the 2023 urban dataset exhibited higher variability and later activity peaks due to warmer microclimatic conditions.

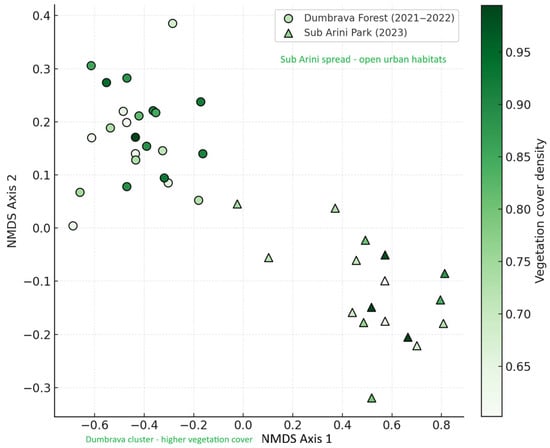

3.5. Inter-Site Community Similarity

Bray–Curtis similarity (BC) and Jaccard index (J) analyses revealed moderate overlap between communities: BC = 0.46, J = 0.39, indicating distinct assemblages shaped by contrasting management regimes. Non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) ordination (stress = 0.09) separated samples from the two ecosystems along the first axis, corresponding to vegetation cover and soil disturbance gradient (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

NMDS ordination of beetle assemblages across sampling sites (stress = 0.09). Circles represent Dumbrava traps; triangles denote Sub Arini traps. Color gradient reflects vegetation cover density. Note: Labels were repositioned to avoid overlap.

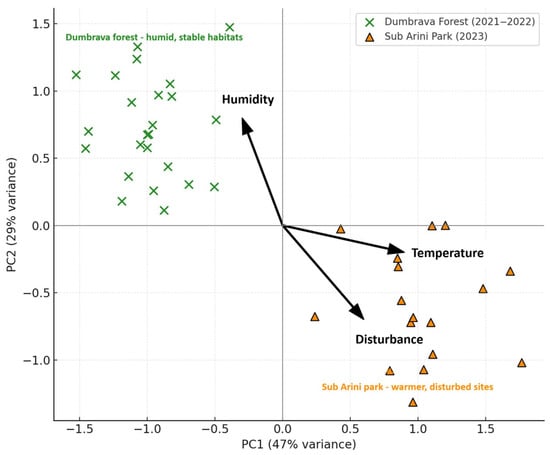

3.6. Climatic Correlations and Model Outputs

Generalized Linear Models (GLMs) showed that beetle abundance was significantly influenced by mean monthly temperature (β = 0.43, p = 0.017) and precipitation (β = −0.32, p = 0.042), explaining R2 = 0.64 of total variance. Model residuals met homoscedasticity assumptions, confirming robustness.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA; Figure 9) grouped species according to their ecological affinities: Axis 1 (47% variance) reflected microclimatic and soil humidity gradients, Axis 2 (29%) captured anthropogenic disturbance and canopy openness. Predatory species (Carabus coriaceus, Pterostichus melanarius) were associated with shaded forest sectors, while generalists (Harpalus affinis, Amara familiaris) clustered within open, disturbed urban plots.

Figure 9.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of beetle species in relation to environmental variables. Vectors represent significant climatic predictors (temperature, humidity, disturbance index). Note: Data represent mean values at the species level aggregated by guild; abundance expressed as individuals/trap/day (mean ± SD). Labels were repositioned to avoid overlap.

3.7. Species of Conservation and Ecological Importance

Several forest-associated species (Carabus coriaceus, Abax parallelepipedus, Pterostichus niger) were restricted to Dumbrava Forest, suggesting high conservation value of this semi-natural woodland.

Conversely, Harpalus affinis, Amara aenea, and Ontholestes murinus were more frequent in Sub Arini Park, indicating tolerance to anthropogenic stress (Table 3).

Table 3.

Species of conservation relevance recorded during the study, with dominance category (D), constancy class (C), and ecological significance (W).

4. Discussion

The comparative analysis of beetle assemblages from Dumbrava Forest and Sub Arini Park provides valuable insights into the ecological structure, diversity, and functional roles of coleopteran communities in two contrasting urban ecosystems of Sibiu. By integrating multi-annual monitoring (2021–2023) with ecological indices, the study reveals both similarities and marked differences shaped by habitat type, vegetation heterogeneity, and anthropogenic pressures.

4.1. General Patterns and Community Structure

The comparative assessment of beetle assemblages between Dumbrava Forest and Sub Arini Park highlights distinct ecological trajectories resulting from divergent management regimes, habitat complexity, and microclimatic conditions. Both ecosystems sustained diverse communities dominated by Carabidae, consistent with previous studies identifying this family as a reliable bioindicator of forest integrity and disturbance gradients [39,40,41,42,60].

In Dumbrava Forest, the prevalence of Pterostichus niger, P. melanarius, and Abax parallelepipedus reflects a community structured around generalist frequently occurring in forest habitats, typically associated with mature oak–hornbeam stands and shaded litter layers [3,43,52]. Conversely, Sub Arini Park, characterized by anthropogenic heterogeneity and mixed exotic vegetation, was dominated by Carabus violaceus, Amara familiaris, and Harpalus affinis, taxa known for their high ecological plasticity and tolerance to heat-island effects [7,11,47].

These findings align with urban–rural gradients documented elsewhere in Central Europe, where peri-urban forests retain relict faunal assemblages while urban parks favor adaptable generalists [8,9,53].

4.2. Species Richness, Diversity, and Evenness

Despite the smaller area, Sub Arini Park exhibited slightly higher species richness and Shannon diversity (H′ = 2.31) compared with Dumbrava Forest (H′ = 2.12), confirming that structural mosaicism and vegetation heterogeneity enhance local species diversity [68,71,90,91,92,93,94]. The higher evenness (J′ = 0.81) observed in the park suggests that no single taxon monopolized resources, while the more pronounced dominance pattern in Dumbrava reflects habitat stability but reduced niche diversity.

These results corroborate the intermediate disturbance hypothesis, which predicts maximal diversity at moderate disturbance levels due to increased niche heterogeneity [3,10,15,35,36,37,38]. However, excessive anthropogenic influence may destabilize communities by favoring opportunistic taxa, as observed in other European cities [7,8,9].

4.3. Functional Guild Composition

Functional guild analysis revealed that predators comprised over two-thirds of the total catch, emphasizing their key role in soil trophic regulation and decomposition processes. Dumbrava’s predator dominance (≈72%) supports the hypothesis that closed-canopy forests favor stable carabid populations through abundant detrital prey [31,32,33,34,39]. In contrast, the higher proportion of saprophagous and phytophagous species in Sub Arini (≈46%) reflects the park’s richer detrital input, ornamental flora, and microclimatic variability.

Such guild restructuring mirrors patterns reported in Mediterranean and Central-European urban greenspaces, where omnivores and decomposers expand under mild microclimates and increased organic matter [7,47,60]. The balance among guilds indicates that both sites maintain functional redundancy—an essential element of ecosystem resilience under climate stress [53,54,55,56,57].

4.4. Temporal Dynamics and Climatic Drivers

Seasonal activity patterns exhibited clear bimodal peaks—spring and autumn—with site-specific timing influenced by temperature and humidity. The first peak (April–May) was dominated by Carabus coriaceus and Abax parallelepipedus, while the second (September–October) was more pronounced in Sub Arini Park, largely driven by Harpalus and Amara species. Although the numerical differences appear small, they are ecologically relevant given the low overall beetle activity densities recorded across sites.

Data from 2021 to 2022 in Dumbrava Forest showed relatively stable seasonal profiles, whereas the 2023 urban dataset displayed greater temporal variability and later activity peaks, reflecting the warmer microclimatic conditions typical of urban environments.

Generalized Linear Models (GLMs) indicate that temperature has a significant positive effect, while precipitation showed a negative influence on beetle abundance, confirming the sensitivity of epigeic beetles to microclimatic fluctuations. These relationships illustrate how thermal and moisture dynamics shape community composition and seasonal activity intensity.

The extended activity period in Sub Arini Park during warmer months exemplifies the urban heat-island effect, a phenomenon increasingly documented across European cities [31,32,33,34,46]. In contrast, Dumbrava Forest, with its more buffered microclimate and dense canopy, maintained stable phenological patterns and preserved assemblages of forest-associated species.

Such temporal differentiation emphasizes the importance of integrating phenological monitoring into long-term biodiversity assessments, as urban warming can alter reproductive cycles, trophic interactions, and the ecological balance between generalist and specialist taxa [39,40,41,42,60].

4.5. Spatial Ordination and Environmental Correlates

Multivariate analyses (NMDS and PCA) revealed clear segregation between forest and park assemblages along vegetation cover and disturbance gradients [83,95,96]. In NMDS space (stress = 0.09), Dumbrava traps clustered in high-shade, high-humidity quadrants, while Sub Arini plots spread across open, disturbed areas. PCA axes associated temperature and disturbance with generalist taxa (e.g., Harpalus affinis), and humidity with forest specialists (Carabus coriaceus, Pterostichus melanarius). These patterns indicate that vegetation structure and soil microclimate are the strongest environmental predictors of community composition, confirming similar findings in temperate Europe [46,97,98,99,100]. They also highlight the importance of maintaining canopy heterogeneity and soil moisture balance as biodiversity safeguards under climate variability.

4.6. Conservation Implications

From a conservation perspective, both habitats demonstrate substantial ecological value, although through different functional pathways. Dumbrava Forest acts as a refugium for forest-associated beetles such as Carabus coriaceus and Abax parallelepipedus, which are widespread but valuable indicators of mature, structurally complex oak–hornbeam stands. The preservation of these habitats should prioritize the maintenance of old-growth trees, coarse woody debris, and stable microclimatic conditions, all of which sustain specialist predators and decomposers characteristic of temperate forests [24,25,26,27,28,29,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,101,102,103,104,105,106,107].

In contrast, Sub Arini Park, despite its anthropogenic management and high visitor pressure, supports a functionally diverse assemblage dominated by generalists and decomposer species. This highlights its role as an urban biodiversity reservoir, contributing to ecological connectivity, pollination services, and public awareness of conservation issues.

Integrating beetle monitoring into local management aligns with European biodiversity and climate adaptation objectives—particularly the EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030 and the Nature-Based Solutions framework. Adaptive management should therefore focus on selective mowing, retention of deadwood and leaf litter, structural diversification of vegetation, and the creation of shaded–open habitat mosaics. Such measures would enhance ecological resilience, sustain soil processes, and improve the functional complementarity between peri-urban forests and urban green spaces [53,54,55,56,57,108,109,110,111,112,113].

4.7. Broader Context and Future Directions

This study provides one of the first multi-annual datasets from Central-Eastern Europe comparing peri-urban and urban coleopteran assemblages under current climatic conditions. The results reinforce that landscape heterogeneity and sustainable management mediate biodiversity resilience. Future work should expand sampling to other Transylvanian green infrastructures, employ molecular tools (DNA metabarcoding) for finer taxonomic resolution, and integrate remote sensing to track vegetation–fauna interactions. Long-term datasets such as this are essential to detect early ecological signals of urbanization and climate change, bridging local observations with continental-scale conservation monitoring.

5. Conclusions

This study provides a multi-annual comparative assessment of beetle assemblages along an urban–peri-urban gradient in Sibiu, Romania, under present climatic variability. The results reveal the distinct yet complementary ecological roles of the two investigated habitats.

Dumbrava Forest, a semi-natural peri-urban woodland, supports abundant populations of forest-associated carabids such as Pterostichus melanarius, Abax parallelepipedus, and Carabus coriaceus. Their dominance reflects stable microclimatic conditions, structural continuity, and limited disturbance—attributes essential for maintaining long-term biodiversity in temperate oak–hornbeam ecosystems. Conversely, Sub Arini Park, situated within the urban core, hosts a more functionally diverse beetle community dominated by thermophilous and generalist taxa (Harpalus affinis, Amara familiaris), indicating high ecological plasticity and adaptation to anthropogenic stress and habitat fragmentation.

Predatory guilds remained dominant in both systems, confirming the persistence of essential regulatory functions within urban and peri-urban ecological networks. Climatic variables—particularly temperature and precipitation—proved to be key drivers of beetle abundance and seasonal dynamics, emphasizing the sensitivity of epigeic fauna to microclimatic shifts.

From a conservation and management perspective, this case study highlights the ecological complementarity of Dumbrava Forest and Sub Arini Park and provides practical recommendations for biodiversity-friendly management within the Sibiu region. Maintaining old-growth stands, coarse woody debris, and soil microhabitats in Dumbrava Forest, together with selective mowing, native tree planting, and microhabitat diversification in Sub Arini Park, can enhance the ecological resilience and connectivity of both habitats.

Future perspectives should include the establishment of long-term insect monitoring programs and the integration of advanced analytical methods (e.g., trait-based and molecular approaches) to refine species identification and evaluate biodiversity responses to ongoing climate and land-use changes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.S.-M., G.M., C.F.B., A.Ș. and L.G.; methodology, C.S.-M. and G.M.; software, C.S.-M., L.G., A.Ș. and C.F.B.; validation, C.S.-M., G.M., C.F.B. and A.Ș.; formal analysis, C.S.-M. and G.M.; investigation, C.S.-M. and G.M.; resources, C.S.-M., G.M. and A.Ș., data curation, C.S.-M., G.M., L.G., A.Ș. and C.F.B.; writing—original draft preparation, C.S.-M., G.M. and A.Ș.; writing—review and editing, C.S.-M., G.M., A.Ș. and C.F.B.; visualization, C.S.-M., G.M., C.F.B., L.G. and A.Ș.; supervision, C.S.-M., G.M. and A.Ș.; project administration, C.S.-M.; funding acquisition, C.S.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Project financed by Lucian Blaga University of Sibiu through the research grant LBUS-IRG No.3547/24 July 2023.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The article is written in memory of Victor Ciochia, one of the greatest specialists in Entomology and biodiversity conservation in Romania. The authors would like to thank all of the people who participated in the studies, especially Norman Frankel, Benjamin Sanislau, Dorina Sanislau, Nicoleta Banea, Elena Luca and Elena Basarabă.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Lindenmayer, D.B.; Franklin, J.F.; Fischer, J. General management principles and a checklist of strategies to guide forest biodiversity conservation. Biol. Conserv. 2006, 131, 433–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, S.J.; Abiem, I.; Abu Salim, K.; Aguilar, S.; Allen, D.; Alonso, A.; Anderson-Teixeira, K.; Andrade, A.; Arellano, G.; Ashton, P.S.; et al. ForestGEO: Understanding forest diversity and dynamics through a global observatory network. Biol. Conserv. 2021, 253, 108907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaia, G.; Dragomir, I.M.; Duduman, M.L. Diversity of Beetles Captured in Pitfall Traps in the S, inca Old-Growth Forest, Bras, ov County, ov, Romania. Forest Reserve versus Managed Forest. Forests 2023, 14, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luick, R.; Reif, A.; Schneider, E.; Grossmann, M.; Fodor, E. Virgin forests in the heart of Europe. The importance, current situation and future of Romania’s virgin forests. Bucov. For. 2021, 21, 105–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olenici, N.; Fodor, E. The diversity of saproxylic beetles’ community from the Natural Reserve Voievodeasa Forest, North-Eastern Romania. Ann. For. Res. 2021, 64, 31–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, I.E.; Gostin, I.N.; Blidar, C.F. An overview of the mechanisms of action and administration technologies of the essential oils used as green insecticides. AgriEngineering 2024, 6, 1195–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cárdenas, A.M.; Gallardo, P.; Salido, Á.; Márquez, J. Effects of Environmental Traits and Landscape Management on the Biodiversity of Saproxylic Beetles in Mediterranean Oak Forests. Diversity 2020, 12, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-L.; Huang, L.-M.; Xiang, Z.-Y.; Zhao, J.-N.; Yang, D.-L.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.-J. Influence of Floral Strip Width on Spider and Carabid Beetle Communities in Maize Fields. Insects 2024, 15, 993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabon, V.; Laurent, Y.; Georges, R.; Quénol, H.; Dubreuil, V.; Bergerot, B. Microhabitat Structure Affects Ground-Dwelling Beetle Communities in Urban Grasslands. Diversity 2024, 16, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ieniștea, M.A. Contribuții la cunoașterea fauna de coleoptere cavernicolous fauna of the RPR. Bul. Științific Secția Științe Biol. Agron. Geol. Geogr. 1955, 7, 410–426. [Google Scholar]

- Magura, T.; Horváth, R.S.; Mizser Tóth, M.; Lövei, G.L. Differences in Morphology of Rural vs.Urban Individuals of the Flightless Ground Beetle, Carabus convexus. Insects 2025, 16, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egorov, L.V.; Filippov, A.E.; Egorov, V.L.; Babenko, A.B.; Belskaya, E.A.; Kostyukov, V.V.; Dudko, R.Y.; Makarov, K.V.; Polilov, A.A.; Petrov, A.V. Regional Coleoptera Fauna: Applying Different Methods to Explore Biodiversity. Insects 2024, 15, 917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gîdei, P.; Popescu, I.E. Guide to Coleoptera of Romania, Vol. I; Editura PIM Iași: Iași, Romania, 2012; p. 533. [Google Scholar]

- Popa, I.; Sustr, V. Collembola (Hexapoda) from Mehedinți Mountains (SW Carpathians, Romania), with four new records for the Romanian fauna. Travaux de l’Institut de Spéologie E. Racovitza LV 2016, 55, 119–128. [Google Scholar]

- Tóthmérész, B.; Magura, T. Diversity and scalable diversity characteristics. European Carabidology. In Proceedings of the 1st European Meeting 2003, Athens, Greece, 16 April 2003; DIAS Report: Delhi, India, 2005; Volume 114, pp. 353–368. [Google Scholar]

- Mouhoubi, D.; Djenidi, R.; Bounechada, M. Contribution to the study of entomofauna of the saline wetland of chott of Beida in Algeria. J. Entomol. Zool. Stud. 2018, 6, 317–323. [Google Scholar]

- Mouhoubi, D.; Djenidi, R.; Bounechada, M. Contribution to the Study of Diversity, Distribution, and Abundance of Insect Fauna in Salt Wetlands of Setif Region, Algeria. Int. J. Zool. 2019, 2019, 2128418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gîdei, P.; Popescu, I.E. Guide to Coleoptera of Romania, Vol. II; Editura PIM Iași: Iași, Romania, 2014; p. 531. [Google Scholar]

- Von Thaden, J.; Tejedor Garavito, N.; Medina, M.C.; Cordero, D.; González, R.; Céspedes, G.; Méndez, M. Half-Century of Forest Change in a Neotropical Peri-Urban Landscape: Land Use Dynamics and Forest Recovery. Land 2022, 11, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smetana, A. (Ed.) Catalogue of Palaearctic Coleoptera, Elateroidea, Derodontoidea, Bostrichoidea, Lymexyloidea, Cleroidea and Cucujoidea; Apollo Books: New York, NY, USA, 2007; Volume 4, p. 935. [Google Scholar]

- Nabozhenko, M.V.; Löbl, I. Tribe Helopini Latreille, 1802. In Catalog of Palaearctic Coleoptera Vol. 5 Tenebrioidea; Löbl, I., Smetana, A., Eds.; Apollo Books: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 241–257. [Google Scholar]

- Nabozhenko, M.V.; Keskin, B. Taxonomic Review of the Genus Helops Fabricius, 1775 (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae) of Turkey; Caucasian Entomological Bulletin: Rostov-on-Don, Russia, 2017; Volume 13, pp. 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemeth, T.; Dusánek, V.; Meterlik, J.; Kundrata, R. New distributional data on Elateroidea (Coleoptera: Elateridae, Eucnemidae and Omalisida) for Albania. Monten. Maced. Elateridariu 2014, 8, 112–117. Available online: http://www.elateridae.com/elateridarium (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- Stan, M.; Serafim, R.; Maican, S. Data on the Beetle Fauna (Insecta: Coleoptera) in Frumoasa Site of Community Importance (ROSCI0058, Romania) and its Surroundings. Trav. Muséum Natl. Hist. Nat. Grigore Antipa București 2016, 59, 129–159. [Google Scholar]

- Nitzu, E.; Nae, A.; Giurginca, A.; Popa, I. Invertebrate communities from the mesovoid shallow substratum of the Carpatho-Euxinic area. Trav. Inst. Spéologie E. Racovitza XLIX 2010, 49, 41–80. [Google Scholar]

- Fleck, E. Die Coleopteren Rümaniens. Bull. Soc. Sci. Buchar.-Romania. State Print. Buchar. 1904, 13, 135. [Google Scholar]

- Petri, K. Siebenbürgens Käferfauna auf Grund ihrer Erforschung bis zum Jahre 1911. Sieben. Ver. Naturwissenschaften Hermannstadt 1912, 3, 376. [Google Scholar]

- Telesca, L.; Aromando, A.; Faridani, F.; Lovallo, M.; Cardettini, G.; Abate, N.; Papitto, G.; Lasaponara, R. Exploring Long-Term Anomalies in the Vegetation Cover of Peri-Urban Parks Using the Fisher-Shannon Method. Entropy 2022, 24, 1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuzepan, G.; Tăușan, I. The Genus Lucanus Scopoli, 1763 (Coleoptera:Lucanidae) in the Natural History Museum Collection of Sibiu (Romania). Brukenthal Acta Musei 2013, 3, 451–460. [Google Scholar]

- Bouchard, P.; Smith, A.B.T.; Douglas, H.; Gimml, M.L.; Brunkel, A.J.; Kanda, K. Biodiversity of Coleoptera: Science and Society. In Insect Biodiversity: Science and Society, Volume I, 2nd ed.; Foottit, R.G., Adler, P.H., Eds.; John Wiley and Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 337–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oettel, J.; Lapin, K. Linking Forest management and biodiversity indicators to strengthen sustainable forest management in Europe. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 122, 107275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grove, S.J. Saproxylic insect ecology and the sustainable management of forests. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 2002, 33, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokland, J.N.; Siitonen, J.; Jonsson, B.G. Biodiversity in Dead Wood; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012; p. 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Hernández, A.; Martínez-Falcón, A.P.; Micó, E.; Almendarez, S.; Reyes-Castillo, P.; Escobar, F. Diversity and deadwood-based interaction networks of saproxylic beetles in remnants of riparian cloud forest. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0214920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siewers, J.; Schirmel, J.; Buchholz, S. The efficiency of pitfall traps as a method of sampling epigeal arthropods in litter rich forest habitats. Eur. J. Entomol. 2014, 111, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radu, S. The ecological role of deadwood in natural forests. In Nature Conservation: Concept and Practice; Gafta, D., Akeroyd, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassauce, A.; Paillet, Y.; Jactel, H.; Bouget, C. Deadwood as a surrogate for forest biodiversity: Metaanalysis of correlations between deadwood volume and species richness of saproxylic organisms. Ecol. Indic. 2011, 11, 1027–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunttu, P.; Junninen, K.; Kouki, J. Dead wood as an indicator of forest naturalness: A comparison of methods. For. Ecol. Manag. 2015, 353, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyr, V.; Dvorák, L. Brouci (Coleoptera) Žihle a okolí.7.část. Omalisidae, Lycidae, Lampyridae, Cantharidae, Lymexylidae. Západočeské Entomol. Listy 2013, 4, 77–82. [Google Scholar]

- Lovei, G.L.; Sunderland, K.D. Ecology and behavior of ground beetles (Coleoptera: Carabidae). Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1996, 41, 231–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spence, J.R.; Niemela, J.K. Sampling carabid assemblages with pitfall traps: The madness and the method. Can. Entomol. 1994, 126, 881–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S.; Jennions, M.D.; Zalucki, M.P.; Maron, M.; Watson, J.E.M.; Fuller, R.A. Protected areas and the future of insect conservation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2022, 38, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witkowski, Z.J.; Król, W.; Solarz, W. (Eds.) Carpathi—An List of Endangered Species; WWF and Institute of Nature Conservation, Polish Academy of Sciences: Vienna, Austria; Kraków, Poland, 2003; p. 64. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto, M.Q.; Varandas, S.; Cohen-Shacham, E.; Cabecinha, E. Birds, Bees, and Botany: Measuring Urban Biodiversity After Nature-Based Solutions Implementation. Diversity 2025, 17, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nițu, E.; Olenici, N.; Popa, I.; Nae, A.; Biris, I.A. Soil and saproxylic species (Coleoptera, Collembola, Araneae) in primeval forests from the northern part of South-Easthern Carpathians. Ann. For. Res. 2009, 52, 27–53. [Google Scholar]

- McLean, I.F.G.; Leather, S.R.; Roy, H.E.; Biesmeijer, J.C.; Chapman, D.S.; Dennis, R.L.H.; Fox, R.; Gaston, K.J.; Harrington, R.; Thomas, C.D.; et al. Challenges and Opportunities for Insect Conservation in a Changing World. Conservation 2022, 2, 216–232. [Google Scholar]

- Bartek, Z.; Merenyi, Z.; Illyes, Z.; Gray, Z.; Laszlo, P.; Viktor, J.; Brandt, S.; Papp, L. Studies on the ecophysiology of Tuber aestivum populations in the CarpathoPannonian region. Osterr. Z. Pilzkd. 2010, 19, 221–226. [Google Scholar]

- Ariton, M. Data concetning the diversity of Scarabeoid beetles (Coleoptera, Scarabaeoidaea) from the Vânători Neamț Natural Park (Neamț Countru, Romania). Olten. Stud. Comunicări Științele Nat. 2011, 27, 109–114. [Google Scholar]

- Stoikou, M.G.; Paraskevi, K. The entomofauna on the leaves of two forest species, Fagus sylvatica and Corylus avelana, in Menoikio Mountain of Serres. Entomol. Hell. 2014, 23, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stancă-Moise, C. Study on the Carabidae fauna (Coleoptera, Carabidae) in a forest biota of oak in Sibiu (Romania). Sci. Pap. Ser. Manag. Econ. Eng. Agric. Rural. Dev. 2016, 16, 321–324. [Google Scholar]

- Hurmuzachi, C. Catalogul Coleopterelor Coleopterelor culese from Romania. Bull. Société Sci. Bucar.-Roum. 1901, 11, 336–374. [Google Scholar]

- Fleck, E. Die Coleopteren Rumäniens II. Bull. Buchar. Sci. Soc. 1904, 13, 402–465. [Google Scholar]

- Stancă-Moise, C.; Moise, G.; Rotaru, M.; Vonica, G.; Sanislau, D. Study on the Ecology, Biology and Ethology of the Invasive Species Corythucha arcuate Say, 1832 (Heteroptera: Tingidae), a Danger to Quercus spp. in the Climatic Conditions of the City of Sibiu, Romania. Forests 2023, 14, 1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, G.A.; Belitz, M.W.; Guralnick, R.P.; Tingley, M.W. Standards and Best Practices for Monitoring and Benchmarking Insects. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 8, 579193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaoa, T.; Nielsenb, A.B.; Hedblom, M. Reviewing the strength of evidence of biodiversity indicators for forest ecosystems in Europe. Ecol. Indic. 2015, 57, 420–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowley, L.M.; Ivison, K.; Enston, A.; Garrett, D.; Sadler, J.P.; Pritchard, J.; MacKenzie, A.R.; Hayward, S.A.L. A comparison of sampling methods and temporal patterns of arthropod abundance and diversity in a mature, temperate, Oak woodland. Acta Oecologica 2023, 118, 103873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calo’, L.O.; Winckler-Caldeira, M.V.; da Silva, C.F.; Camara, R.; Castro, K.C.; de Lima, S.S.; Pereira, M.G.; de Aquino, A.M. Epigeal fauna and edaphic properties as possible soil quality indicators in forest restoration areas in Espírito Santo, Brazil. Acta Oecologica 2022, 117, 103870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viciana, V.; Svitok, M.; Michalková, E.; Lukáčikd, I.; Stašiovb, S. Influence of tree species and soil properties on ground beetle (Coleoptera: Carabidae) communities. Acta Oecologica 2018, 91, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudley, N. (Ed.) Guidelines for Applying Protected Area Management Categories; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2013; x + 86 p. [Google Scholar]

- Bredin, Y.K.; Fox, R.; Leather, S.R.; Oliver, T.H.; Roy, H.E.; Shortall, C.R.; Storkey, J.; Pywell, R.F. Conserving Invertebrate Biodiversity in Human-Dominated Landscapes: Policy and Practice Perspectives. Conservation 2023, 3, 45–61. [Google Scholar]

- Bacal, S. Observation on the Coleopteran (Insecta: Coleoptera) fauna from Codrii Tigheciului. Olten. Stud. Comunicări Științele Nat. 2006, 22, 160–163. [Google Scholar]

- Babam, E. The saproxylic Coleoptera as indicators of forests of European importance from central Moldavian Plateau. Olten. Stud. Comunicări Științele Nat. 2008, 24, 121–124. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidl, J.; Sausage, C.; Bussler, H. Red list and complete list of varieties of the “Diversicornia” (Coleoptera) of Germany. In Red List of Endangered Animals, Plants and Fungi of Germany, Volume 5: Invertebrates (Part 3); Nature Protection and Biodiversity; Ries, M., Balzer, S., Gruttke, H., Haupt, H., Hofbauer, N., Ludwig, G., Matzke-Hajek, G., Eds.; Agriculture Publisher: Münster, Germany, 2021; Volume 70, pp. 99–124. [Google Scholar]

- Antvogel, H.; Bonn, A. Environmental parameters and microspatial distribution of insects: A case study of carabids in an alluvial forest. Ecography 2001, 24, 470–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeates, D.K.; Hatvey, M.S.; Austin, A.D. New estimates for terrestrial arthopod species-richness in Australia. Rec. S. Aust. Mus. Monogr. Ser. 2003, 7, 231–241. [Google Scholar]

- Marske, K.A.; Ivie, M.A. Beetle Fauna of the United States and Canada. Coleopt. Bull. 2003, 57, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klausnitzer, B. Käfer; Nikol Verlag: Hamburg, Germany, 2002; p. 242. [Google Scholar]

- Engelmann, H.D. Zur Dominanzklassifizierung von Bodenarthropoden, for the dominance classification of soil arthropods. Pedobiologia 1978, 18, 378–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stugren, B. The Basics of General Ecology; Editura Științifică și Enciclopedică: Bucharest, Romania, 1982; p. 435. [Google Scholar]

- Barkman, J.J.; Moravec, J.; Rauschert, S. Code of Phytosociological Nomenclature, 2nd ed.; Vegetatio: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1986; Volume 67, pp. 145–195. [Google Scholar]

- Dragulescu, C. Cormoflora of Sibiu County; Pelecanus Publishing House: Brasov, Romania, 2003; p. 533. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider-Binder, E. Forests of the Sibiului depression and marginal hills I. St. Com. Muz. Brukenthal Sibiu Șt. Nat. 1973, 18, 71–108. [Google Scholar]

- Stancă-Moise, C. The presence of species Morimus asper funereus Mulsant, 1862 (long-horned beetle) Coleoptera: Cerambycidae in a forest of oak conditions. Sci. Pap. Ser. Manag. Econ. Eng. Agric. Rural. Dev. 2015, 15, 315–318. [Google Scholar]

- Zicha, O. (Ed.) 1999–2021. BioLib. Available online: http://www.biolib.cz (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Koch, K. Die Käfer Mitteleuropas. In Ökologie. The Beetles of Central Europe. Ecology. Band 1; Goecke & Evers: Krefeld, Germany, 1989; p. 440. [Google Scholar]

- Koch, K. Die Käfer Mitteleuropas. In Ökologie. The Beetles of Central Europe. Ecology. Band 3; Goecke & Evers: Krefeld, Germany, 1992; p. 389. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidl, J.; Bussler, H. Ökologische Gilden xylobionter Käfer Deutschlands. Einsatz in der landschaftsökologischen Praxis ein Bearbeitungsstandard. Naturschutz Landschaftsplanung 2004, 36, 202–218. [Google Scholar]

- Lobl, I.; Smetana, A. (Eds.) Catalogue of Palaearctic Coleoptera, Archostemata, Myxophaga, Adephaga; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2003; Volume 1, p. 819. [Google Scholar]

- Lobl, I.; Smetana, A. (Eds.) Catalogue of Palaearctic Coleoptera, Tenebrioidea; Apollo Books: New York, NY, USA, 2008; Volume 5, p. 670. [Google Scholar]

- Lobl, I.; Lobl, D. (Eds.) Catalogue of Palaearctic Coleoptera, Hydrophiloidea, Staphylinoidea; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2015; Volume 2, p. 1702. [Google Scholar]

- Lobl, I.; Lobl, D. (Eds.) Catalog of Palaearctic Coleoptera, Scarabaeoidea, Scirtoidea, Dascilloidea, Buprestoidea and Byrrhoidea; Apollo Books: New York, NY, USA, 2016; Volume 3, p. 984. [Google Scholar]

- Nieto, A.; Alexander, K.N.A. European Red List of Saproxylic Beetles; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2010; p. 44. [Google Scholar]

- Murariu, D.; Maican, S. (Eds.) The Red Book of Invertebrates of Romania; ThePublishing House of the Romanian Academy: Bucharest, Romania, 2021; p. 451. [Google Scholar]

- Dremel, M.; Goličnik Marušić, B.; Zelnik, I. Defining Natural Habitat Types as Nature-Based Solutions in Urban Planning. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dajoz, R. Rôle et diversité des insectes dans le milieu forestier. In Les Insectes et la Forêt; Lavoisier Tec Doc: Paris, France, 1998; p. 594. [Google Scholar]

- Dajoz, R. Morphological study of the Morimus (Coleoptera, Cerambycydae) of the European fauna. Entomologist 1976, 67, 212–231. [Google Scholar]

- Directive 97/62/EC of 27.10.1997; Council Directive 97/62/EC of 27 October 1997 Adapting to Technical and Scientific Progress Directive 92/43/EEC on the Conservation of Natural Habitats and of Wild Fauna and Flora. European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 1997.

- Stichmann, W. Faune d’Europe; Vigot: Paris, France, 1999; p. 448. [Google Scholar]

- Magurran, A.E. Measuring Biological Diversity; Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2004; p. 256. [Google Scholar]

- Magurran, A.E. Species abundance distributions: Pattern or process. Funct. Ecol. 2005, 19, 177–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magurran, A.E. Diversity over time. Folia Geobot. 2008, 43, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitzu, E. Eco-faunistic studies on edaphic coleopteran associations in the Sic-Păstăraia area (Transylvanian Plain). Ann. ICAS 2007, 50, 153–167. [Google Scholar]

- Matern, A.; Drees, C.; Kleinwächter, M.; Assmann, T. Habitat modeling for the conservation of the rare ground beetle species Carabus variolosus (Coleoptera, Carabidae) in the riparian zones of headwaters. Biol. Conserv. 2007, 136, 618–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolton, S.; Shadie, P.; Dudley, N. IUCN WCPA Best Practice Guidance on Ecognizing Protected Areas and Assigning Management Categories and Governance Types, Best Practice Protected Area Guidelines Series No. 21; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2008; x, 86 p. + iv, 31 p. [Google Scholar]

- Council Directive 92/43/EEC of 21 May 1992 on the Conservation of Natural Habitats and of Wild Fauna and Flora (Habitats Directive). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CONSLEG:1992L0043:20070101:en:PDF (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- Telesca, L.; Lovallo, M.; Cardettini, G.; Aromando, A.; Abate, N.; Proto, M.; Loperte, A.; Masini, N.; Lasaponara, R. Urban and Peri-Urban Vegetation Monitoring Using Satellite MODIS NDVI Time Series, Singular Spectrum Analysis, and Fisher–Shannon Statistical Method. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Săvulescu, N. The Forests of South-West Dobrogea, little known monuments of nature. Ocrotirea Nat. 1964, 8, 257–276. [Google Scholar]

- Stancă-Moise, C. Observations of the Lucanus cervus Linnaeus, 1758 (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae) species in the Sibiu and Hunedoara counties in the conditions of 2020. Olten. Mus. Craiova. Oltenia. Stud. Commun. Nat. Sci. 2021, 37, 76–82. [Google Scholar]

- Ruicănescu, A. Contributions to the study of coleopteran communities in Cheile Turzii. Entomol. Inf. Bull. Rom. Lepidopterol. Soc. Cluj-Napoca 1992, 3, 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Koivula, M.J. Useful model organisms, indicators, or both? Ground beetles (Coloptera, Carabidae) reflecting environmental conditions. ZooKeys 2011, 100, 287–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brygadyrenko, V. Evaluation of ecological niches of abundant species of Poecilus and Pterostichus (Coleoptera: Carabidae) in forests of steppe zone of Ukraine. Entomol. Fenn. 2016, 27, 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponnel, P. Coleoptera of the Massif des Maures and the Permian Peripheral Depression. In Faune de Provence; French Federation of Natural Science Societies: Paris, France, 1993; pp. 5–23. [Google Scholar]

- Schulze, E.D. Effects of forest management on biodiversity in temperate deciduous forests: An overview based on Central European beech forests. J. Nat. Nat. Conserv. 2018, 43, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Błońska, E.; Bednarz, B.; Kacprzyk, M.; Piaszczyk, W.; Lasota, J. Effect of scots pine forest management on soil properties and carabid beetle occurrence under post-fire environmental conditions- a case study from Central Europe. For. Ecosyst. 2020, 7, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazerani, F.; Farashiani, M.E.; Sagheb-Talebi, K.; Thorn, S. Forest management alters alpha, beta, and gamma diversity of saproxylic flies (Brachycera) in the Hyrcanian forests. Iran. For. Ecol. Manag. 2021, 496, 119444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGeoch, M.A. The selection, testing and application of terrestrial insects as bioindicators. Biol. Rev. 1998, 73, 181–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGeoch, M.A.; Schroeder, M.; Ekbom, B.; Larsson, S. Saproxylic beetle diversity in a managed boreal forest: Importance of stand characteristics and forestry conservation measures. Divers. Distrib. 2007, 13, 418–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, P.; Fortin, D.; Hébert, C. Beetle diversity in a matrix of old-growth boreal forest: Influence of habitat heterogeneity at multiple scales. Ecography 2009, 32, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, M.S.; Gage, S.H.; Spence, J.R. Habitats and management associated with common ground beetles (Coleoptera:Carabidae) in a Michigan Aricultural landscape. Environ. Entomol. 1997, 26, 519–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worell, E. Contributions to the knowledge of the fauna of coleoptera and lepidoptera in Transylvania, especially in the surroundings of Sibiu. Sci. Bull. Sect. Biol. Agron. Geol. Geogr. Sci. 1951, 3, 533–543. [Google Scholar]

- Byk, A.; Semkiw, P. Habitat preferences of the forest dung beetle Anoplotrupes stercorosus (Scriba, 1791)(Coleoptera: Geotrupidae) in the Białowieza Forest. Acta Sci. Pol. Silvarum Colendarum Ratio Ind. Lignaria 2010, 9, 17–28. [Google Scholar]

- Esh, M.; Oxbrough, A. Macrohabitat associations and phenology of carrion beetles (Coleoptera: Silphidae, Leiodidae: Cholevinae). J. Insect Conserv. 2021, 25, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zumr, V.; Remeš, J.; Nakládal, O. Short-Term Response of Ground Beetles (Coleoptera: Carabidae) to Fire in Formerly Managed Coniferous Forest in Central Europe. Fire 2024, 7, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).