Abstract

Anthropogenic pressures and climate change have increasingly affected biodiversity and ecosystem services, particularly in freshwater ecosystems, which are among the most sensitive and vulnerable environments. Citizen science has emerged as a promising approach to expand ecological knowledge and strengthen biomonitoring efforts, mitigating the limitations of conventional research in scale, cost, and speed. This study presents a global bibliometric analysis of citizen science applied to freshwater biomonitoring using aquatic insects. A total of 153 articles indexed in Scopus and Web of Science, published between 2002 and 2025, were analyzed. Results reveal a marked increase in publications since 2010, concentrated mainly in the Global North, especially the United States (37.51%) and Germany (14.42%). The most frequent taxa were Odonata (25.58%) and Diptera (25.19%), with studies focusing primarily on species (70.59%) level, and adult stage (69%). Participants were mainly from the general public (70%) and naturalists (12%), predominantly under contributory models (98%). Reported challenges involved taxonomic limitations (28%) and citizen science engagement (28%). Despite these constraints, the findings highlight the growing relevance of citizen science as a complementary tool for aquatic biomonitoring, emphasizing the need for inclusive approaches, taxonomic training, and participatory strategies in biodiversity conservation.

1. Introduction

The current global environmental crisis, coupled with the accelerated loss of biodiversity, necessitates agile, more inclusive, and innovative strategies for monitoring and conserving natural ecosystems [1,2]. Among the different ecosystems affected, aquatic environments stand out for their high vulnerability and ecological importance [3]. The degradation of these systems has intensified due to pollution, climate change, overfishing, hydrological fragmentation, and the loss of marginal habitats [2,4,5]. Such ecosystems support extraordinary biodiversity and provide essential services, including water supply, climate regulation, food security, and livelihoods for millions of people [6,7].

Despite their ecological and social importance, freshwater ecosystems have historically been underrepresented in global conservation policies when compared to terrestrial and marine environments [8,9]. This imbalance limits the global understanding of socioecological dynamics and often renders local and traditional knowledge invisible, knowledge that could contribute valuable alternatives for conservation in biodiverse regions [10]. This underrepresentation is also evident in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the UN’s 2030 Agenda: SDG 14 (Life Below Water) emphasizes ocean and marine conservation [11], SDG 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation) focuses on water management for human use [12], and SDG 15 (Life on Land) only marginally addresses freshwater ecosystems, despite their hosting over 10% of known species and being among the most threatened [11,13,14]. This gap hinders the establishment of sound conservation priorities and the implementation of effective strategies—particularly in biodiversity-rich regions such as the Amazon [15,16].

Faced with the challenges of large-scale environmental monitoring and data scarcity in many regions, citizen science has emerged as a promising strategy in this field [17]. This approach enables the generation of open, holistic, and participatory knowledge, while also promoting direct public involvement in the collection and interpretation of scientific data, expanding the spatial coverage of research, and strengthening the links between science and society [18,19]. These processes also contribute to the redefinition of naturalistic knowledge production and to the democratization of epistemic practices, by promoting dialogue between scientific and local knowledge. Citizen science is a pillar of open science, supporting universities and promoting the co-production of research that benefits society [20,21]. In the environmental field, it stands out for its potential to generate data in remote locations and democratize access to knowledge [17]. This potential is particularly relevant for the biomonitoring of aquatic ecosystems, as citizen participation expands the collection of data on bioindicator organisms, such as aquatic insects, in areas that are difficult to access, contributing to more inclusive conservation strategies based on robust data [22].

Although such initiatives are expanding globally, there are still few studies that systematize the use of aquatic insects in citizen science projects, identifying regional and taxonomic gaps and their potential impacts on public policy and conservation [17]. This lack of comprehensive analysis limits the development of effective participatory strategies, particularly in tropical contexts, while also detracting from the importance and urgency of discussions on conservation and ensuring quality water for people, especially the poorest, who suffer most in areas of scarcity or contaminated water.

Despite this global underrepresentation, some national initiatives demonstrate promising pathways for integrating participatory science into biodiversity monitoring. In Brazil, for instance, the Monitora Project of the Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation (ICMBio), which uses aquatic insects as bioindicators in protected areas, has demonstrated the importance of participatory monitoring in biodiversity protection [23]. The Monitora Project integrates citizen science with adaptive management, involving local communities, researchers, and managers in long-term protocols for biodiversity conservation [24]. However, such initiatives remain underrepresented in the international scientific literature, highlighting the need for greater visibility and systematization of these data on a global scale [17] despite their importance and capacity for large-scale use.

In this context, the study aims to conduct a global bibliometric analysis of scientific literature evaluating citizen science as a tool in the biomonitoring of freshwater ecosystems using aquatic insects, with the goal of identifying thematic, taxonomic, geographic, and methodological patterns. To this end, eight guiding questions were developed: (i) What is the global temporal trend in research? (ii) What is the geographical distribution of the most studied areas? (iii) What are the most relevant research topics? (iv) Which insect orders are frequently studied? (v) What is the most studied taxonomic level? (vi) Which life stages have been most researched? (vii) What is the profile of participants, and what are their levels of engagement? (viii) What are the main practical and methodological challenges described in the studies? This type of analysis will provide essential information to clarify the research context and serve as a basis for directing future citizen science, conservation, and aquatic ecosystem monitoring efforts to the areas that need them most.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search and Selection Process

To investigate trends and identify gaps in research on citizen science as a tool for biomonitoring freshwater ecosystems using aquatic insects, a literature review was conducted based on articles published in the Scopus (Elsevier) and Web of Science-WoS (Clarivate Analytics) databases, which are recognized for their interdisciplinary coverage and reliability in citation analysis [16,25]. The keywords were defined based on synonyms identified in the literature on aquatic insects and citizen science. The search strategy used in both databases was: Title/Abstract/Keywords (Scopus)/Topic (WoS) ((“aquatic insects” OR “freshwater insects” OR macroinvertebrates OR Odonata* OR Anisoptera* OR Zygoptera* OR Ephemeroptera* OR Plecoptera* OR Trichoptera* OR Coleoptera* OR Hemiptera* OR Heteroptera* OR Megaloptera* OR Neuroptera* OR Diptera* OR Orthoptera OR Lepidoptera OR Hymenoptera OR Mecoptera) AND (“citizen science” OR “participatory monitoring” OR “community-based monitoring” OR “volunteer monitoring” OR “citizen scientist” OR “participatory science” OR “public participation in scientific research” OR “community science” OR “participatory research” OR “crowdsourced Science” OR “open science”)).

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

During the database search process, reviews, conferences, and book chapters were excluded, thereby restricting the search to peer-reviewed scientific articles, which are considered the most reliable sources for full-text literature reviews [26]. Articles that were not directly related to the research topic were also manually excluded. The document search was limited to articles published between 2002 and 2025. This time frame is justified because the first study identified on the topic was published in 2002, entitled “Volunteer Biological Monitoring: Can It Accurately Assess the Ecological Condition of Streams?” [27], and ends in May 2025, covering as many publications as possible available to date.

There was no restriction on the specific field of study due to the multidisciplinary nature of the topic, which allowed for the gathering of a significant volume of records and ensured a representative sample [16]. The language of publication was also not used as an exclusion criterion, considering that articles in different languages can offer complementary contexts and perspectives [28].

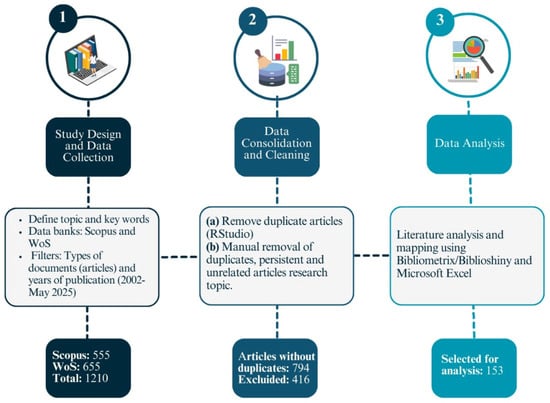

2.3. Data Cleansing Process

A total of 1210 articles were retrieved, 555 from the Scopus database and 655 from Web of Science, all exported in CSV (comma-separated values) format. We used the RStudio program (version 4.1.4) to combine the records from the two databases and automatically remove duplicates. The software was chosen for its robustness in statistical analysis, database integration capabilities, practical algorithms, and support for advanced bibliometric analysis [29]. The integration resulted in a database of 802 documents. We then performed a manual review to identify possible remaining duplicates, as variations in references may not be detected by the software alone [25]. This process was carried out by multiple reviewers to ensure accuracy. After this step, 794 articles remained (Figure 1). Subsequently, we generated a file for detailed analysis of titles, abstracts, keywords, materials, and methods, to identify: (i) temporal distribution of publications; (ii) geographical distribution of the areas studied; (iii) predominant study themes; (iv) insect orders most frequently analyzed; (v) most commonly used taxonomic levels; (vi) most studied life stages; (vii) participant profiles and levels of engagement; and (viii) practical and methodological challenges described in the studies. During this screening, articles were excluded that, although related to citizen science or the monitoring of aquatic ecosystems, did not involve aquatic insects as target organisms, which is the central focus of this study. Studies that did not present a direct link between participatory data collection and the use of aquatic insects as bioindicators were also removed. At the end of this process, 153 articles were selected for in-depth analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the procedure adopted for the collection, organization, filtering, and analysis of articles related to citizen science and biomonitoring using aquatic insects on a global scale. Databases: Scopus and Web of Science (2002—May 2025).

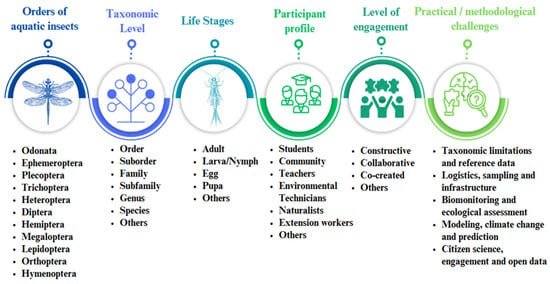

2.4. Organization and Categorization of Information

The information extracted from the articles was organized in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. It was then classified based on categories previously defined in the literature. The degree of citizen involvement in the projects was categorized according to Lameira et al. [17] and Bonney et al. [30] into three main types: (a) Contributory, where citizen scientists play limited roles, usually restricted to data collection and submission of observations; (b) Collaborative, where participants, in addition to data collection, also contribute to specific stages of the scientific process, such as data analysis or dissemination of results; and (c) Co-created, where citizens participate actively and continuously, from project design to execution, analysis, and communication of results, with responsibilities shared between academic scientists and citizens. The typology of participants (students, teachers, community members, technicians, NGOs, naturalists, and university students/extension workers) was defined based on the literature on participation in citizen science [31,32] and adjusted according to the profiles identified in the analyzed articles. The other categories (insect orders, taxonomic levels, and life stages) were constructed based on the organization of the most recurrent criteria found in the literature on aquatic macroinvertebrates [33,34].

The main practical and methodological challenges described in the studies were grouped into categories of analysis that emerged from reading the articles, resulting in five categories: (a) Taxonomic limitations and reference data: Includes articles that indicate Linnean and Wallacean deficits, lack of specialists, limitations for identification at the order, family, and genus levels, and absence of scientific collections to support the findings. (b) Logistics, sampling, and infrastructure: Covers documents that report disparities in sample sizes, spatial and temporal biases in the data collected, under sampling in tropical regions, logistical challenges, costs, and difficult access to remote areas. (c) Biomonitoring and ecological assessment: Articles describing limitations in the use of metrics for ecological assessment, monitoring, and restoration of aquatic ecosystems, as well as the limited use of some insect orders. (d) Modeling, climate change, and prediction: Articles that point to the scarcity of research focused on risk prediction through modeling, as well as the lack of studies addressing the impacts of climate change on water resources. (e) Citizen science, engagement, and open data: Articles that mention the lack of public participation, use of applications, and data from crowdsourcing (collaborative form). They also highlight the lack of initiatives for education and validation of information generated by citizen science projects. Figure 2 visually presents all the categories adopted in the analysis.

Figure 2.

Organization and categorization of information contained in articles. Databases: Scopus and Web of Science (2002—May 2025).

2.5. Data Analysis

To analyze the temporal distribution of the studies, we used a line graph (i), and the Spearman correlation coefficient (ρ), which measures the monotonic association between two ordinal variables. This approach was chosen because it does not require the assumption of normality, which is suitable for count data, such as the annual number of publications The most recurrent research topics were highlighted in a thematic map, positioning the main topics in four quadrants: (i) basic topics (high centrality and low density); (ii) driving topics (high centrality and high density); (iii) niche themes (low centrality and high density); and (iv) emerging or declining themes (low centrality and low density). The size of the spheres indicates the relative frequency of each theme in the literature. At the same time, the position on the X-axis (degree of centrality) and Y-axis (degree of development) represents, respectively, its relevance and maturity in the field of study. The use of thematic maps is widely recommended in bibliometric analyses because they allow the identification of conceptual nuclei, thematic evolution, and emerging gaps in the scientific literature [35]. The other results were displayed in histograms and frequency graphs. All analyses were performed in RStudio software (version R 4.1.4), using the Bibliometrix/Biblioshiny packages (version 4.1.4).

3. Results and Discussion

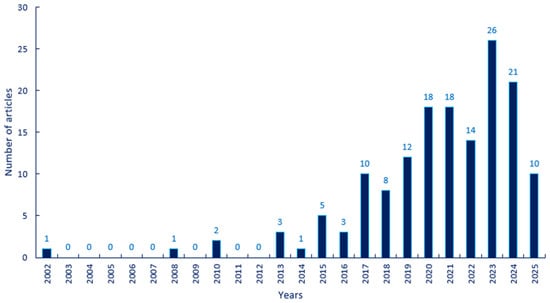

3.1. Temporal Distribution of Publications

In recent years, there has been a significant increase in the number of articles on citizen science applied to the biomonitoring of freshwater ecosystems using aquatic insects (Figure 3). This trend was evidenced by a strong positive monotonic correlation between the year of publication and the number of articles (ρ = 0.877; p < 0.001), indicating a consistent pattern of growth over the analyzed period.

Figure 3.

Annual scientific output on citizen science as a tool in the biomonitoring of freshwater ecosystems using aquatic insects. Databases: Scopus and Web of Science (2002—May 2025).

Temporal analysis allows us to identify three distinct phases in the evolution of publications. Between 2002 and 2014, scientific production was still in its infancy, with few annual records. This initial phase corresponds to an emerging period, before the methodological and institutional consolidation of the field, marked by technological limitations, restricted participatory infrastructure, and low academic visibility of the topic [36]. This scenario can be explained, in part, by the fact that until the mid-2010s, large digital platforms for citizen science, such as Zooniverse (2009) [37], iNaturalist (2008) [38], and CitSci.org (2007) [39], were still in the launch or consolidation phase, with few projects and use restricted to areas such as astrophysics, general biodiversity, and science education. The pioneering example of Galaxy Zoo (2007) and the Zooniverse platform itself demonstrate that expansion into other participatory domains did not occur until 2009, and even then, the application to aquatic ecology remained in its infancy [37,40].

Before this, initiatives such as BBC Lab UK (2008–2012) and Geo-Wiki (2009) demonstrated the potential of public participation, albeit with limited scope, an urban or geographical focus, and rarely addressing aquatic biological indicators using insects [41,42]. The lack of simple tools for identifying aquatic macroinvertebrates, as well as the absence of technologies that facilitate their use, such as robust mobile apps, limited the field’s expansion at that time [43,44]. In practice, the systematic adoption of participatory methods for biomonitoring would require maturity in the areas of data quality control, standardized protocols, and volunteer training, which only intensified after 2014 [45,46].

Between 2015 and 2019, there was an initial expansion in the production of literature on citizen science in aquatic ecology. This phase can be correlated with global initiatives such as the UN’s 2030 Agenda and the SDGs, which include explicit goals for environmental monitoring and biodiversity conservation (SDGs 6 and 15) [8,11,12]. The relevance of citizen science as a method for collecting large-scale spatial and temporal data gained prominence as a response to the lack of institutional capacity in developing countries [47]. At the same time, digital data collection tools were strengthened, especially apps for georeferenced recording using smartphones [48]. New technologies, such as digital cameras, apps, and portable sensors, have become widely used in citizen science projects for monitoring biodiversity and water quality, facilitating the participation of non-specialists without in-depth taxonomic knowledge [17,48].

Between 2020 and 2024, scientific production on citizen science in aquatic ecology experienced exponential growth, reaching its peak in 2023. This trend coincides with an environment favorable to the development of citizen science, driven by the maturation of open science policies, which reinforced open access to data and public involvement in research, a determining factor for expanding citizen participation in knowledge production [47]. In addition, the COVID-19 pandemic (2020–2022) played a central role in changing the format of data collection, leading to the development of hybrid or fully digital projects, with a greater reliance on online platforms and mobile apps [49,50,51]. Another factor that may explain this recent growth is the encouragement of using aquatic insects as bioindicators in participatory contexts [17,52]. Among the most common bioindicators are insects of the order Odonata, the triplet commonly known as EPT (Ephemeroptera, Plecoptera, Trichoptera), and Diptera, which are notable for being highly sensitive to environmental changes. In addition, they are easy to observe in the field, favoring their use in projects with voluntary participation [34,53,54].

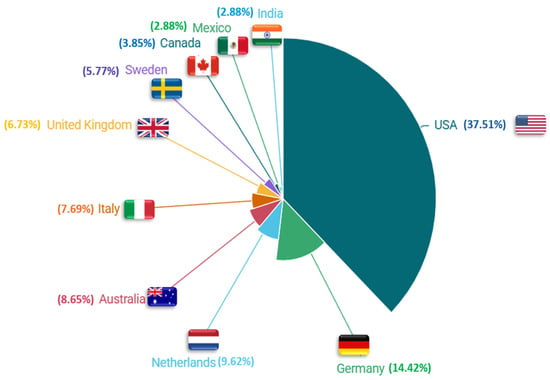

3.2. Geographic Distribution of the Areas Studied

The analysis of the geographical distribution of the most studied countries revealed a clear predominance of the United States (n = 39; 37.51%), followed by Germany (n = 15; 14.42%), the Netherlands (n = 10; 9.62%), Australia (n = 9; 8.65%), Italy (n = 8; 7.69%), and the United Kingdom (n = 7; 6.73%). To a lesser extent, Sweden (n = 6; 5.70%), Canada (n = 4; 3.85%), Mexico (n = 3; 2.88%), India (n = 3; 2.88%), Spain (n = 3; 2.0%), France (n = 3; 2.0%), Switzerland (n = 3; 2.0%), Cyprus (n = 3; 2.0%), New Zealand (n = 3; 2.0%), and Malaysia (n = 3; 2.0%) were also represented. Countries such as South Korea, Indonesia, Denmark, Poland, Hungary, Czech Republic, Brazil, Austria, Bangladesh, and Chile contributed two studies each (n = 2; 1.3%), while Costa Rica, Scotland, Peru, Thailand, Ireland, Myanmar, Pennsylvania, Portugal, Romania, Singapore, Sri Lanka, and Rwanda were represented by one study each (n = 1; 0.6%) (Figure 4). For illustrative purposes, the percentages shown in Figure 4 refer only to the ten most represented countries. However, considering the total number of studies (n = 153), these ten countries together represent 65.2% of all publications, while the remaining countries correspond to 34.8% of the total dataset.

Figure 4.

Distribution of the 10 countries most studied on citizen science as a tool in biomonitoring freshwater ecosystems using aquatic insects. Several studies covered more than one country—databases: Scopus and Web of Science (2002—May 2025).

The predominance of the United States as the leading country studied reflects a recurring pattern identified in several bibliometric reviews in various areas of knowledge [16,25,35,55]. Regardless of the topic, such as conservation, citizen science, aquatic ecology, or biodiversity, there is a concentration of scientific studies in countries in the Global North [24,56]. This asymmetry has been widely attributed to the existence of a consolidated scientific infrastructure, greater availability of funding, robust training systems, and historically established institutional networks [57,58].

As a concrete example, in the United States, the CitizenScience.gov portal provides a catalogue of federal citizen science projects, practical guidelines, and fosters institutional collaboration [45,59]. Similarly, Australia has the national AUSRIVAS (Australian River Assessment System) system, implemented in the 1990s as part of the National River Health Program, inspired by the British RIVPACS model. AUSRIVAS represents a government initiative aimed at standardizing biological monitoring with macroinvertebrates in river basins [60,61].

In contrast, there is a significant underrepresentation of biodiversity-rich countries located in tropical regions, such as Latin America, Sub-Saharan Africa, and Southeast Asia. The predominance of studies conducted in countries such as the United States, Germany, the United Kingdom, and Australia reveals not only an unequal distribution of scientific resources but also a historical pattern of coloniality in knowledge production where, according to Nakamura et al. [62], the international division of scientific labor often confines researchers from the Global South to the role of data providers or field assistants, while theoretical formulation and epistemic authority remain concentrated in the North.

Recognizing such inequalities implies questioning the logic that attributes centrality to the Global North and, at the same time, renders invisible the role of local researchers and communities in building more contextualized and equitable conservation solutions [62]. The absence or low frequency of studies in these territories does not reflect their ecological irrelevance, but rather persistent structural limitations. For example, lack of funding, linguistic and institutional barriers, and unequal access to international databases, as well as limitations in infrastructure and access to remote study areas [22,63,64,65]. These asymmetries exacerbate the Linnean and Wallacean deficits, hindering the development of more accurate diagnoses of biodiversity and environmental quality in regions crucial for conservation [66].

Given this scenario, strengthening citizen science networks in underrepresented countries and increasing the visibility of local initiatives emerge as essential strategies for democratizing knowledge. Global initiatives such as the FreshWater Watch program, developed by Earthwatch Europe, and the CrowdWater app, tested in five Latin American countries, exemplify efforts to reduce these inequalities through community training and the use of accessible and standardized protocols [67,68]. Although these networks are expanding, studies show that challenges such as the disconnect between local and academic goals, technological barriers, and a lack of institutional support still limit the complete consolidation of these initiatives in the Global South [17,69].

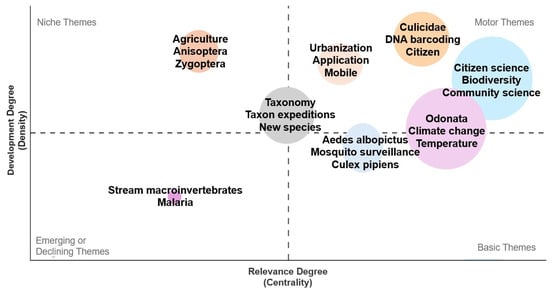

3.3. Predominant Study Topics

The quadrant of driving themes includes citizen science, community science, biodiversity, DNA barcoding, and Culicidae (Figure 5), demonstrating that these terms form the conceptual and methodological core of the literature on citizen science in freshwater biomonitoring using aquatic insects.

Figure 5.

Thematic map on citizen science as a tool in the biomonitoring of freshwater ecosystems using aquatic insects. Databases: Scopus and Web of Science (2002—May 2025).

Studies show that citizen science is deeply linked to classic ecological themes, such as biodiversity and conservation, acting as central elements in both academic research and practical applications [17,70]. The presence of DNA barcoding as a central theme reinforces the incorporation of modern biomolecular methodologies into participatory biomonitoring [10,71,72]. However, this consolidation occurs asymmetrically: most reference databases are concentrated in countries in the Global North, which limits their full applicability in biodiversity-rich regions of the Global South [73]. This is also associated with the high cost of laboratory infrastructure and the low sustainability of specialized centers in low- and middle-income countries, which perpetuates the scarcity of local production in emerging fields such as DNA research [74]. Thus, although barcoding has excellent potential to democratize biological monitoring, its effective adoption still depends on the expansion of tropical genetic libraries and the strengthening of local technical infrastructure, to avoid the reproduction of existing Linnean and Wallacean deficits [72,75].

The terms Culicidae, Malaria, Aedes albopictus, and Culex pipiens, positioned in different quadrants, reveal a relevant epidemiological aspect focused on the development of citizen mosquito surveillance projects. One of them is Mosquito Surveillance, a software that provides predictive indicators of disease transmission. Work carried out by Sousa et al. [76] and Murindahabi et al. [77] demonstrates that data collected by citizens can map the abundance and diversity of vectors in remote areas at a low cost, generating epidemiological and public health insights. This integration between citizen science, molecular genetics, public health, and vector monitoring signals an expansion of the method’s application beyond traditional benthic macroinvertebrates. However, it also raises a relevant point for discussion: the order Diptera is often associated with its role as a disease vector, overshadowing its profound ecological and economic significance. Aquatic and terrestrial Diptera represent essential functional components of aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems, with direct implications for crucial ecosystem services such as pollination, biological control, decomposition of organic matter, and environmental monitoring as indicators of water quality, ecological changes, and climate change [78,79,80].

Flower flies or syrphids (Family Syrphidae) are a prime example of this multifunctionality. During adulthood, many species act as efficient pollinators, visiting a wide range of flowers in both natural and agricultural environments, playing a central role in the conservation of plant biodiversity and the sustainability of pollinator-dependent crops, making them fundamental organisms for global food security [79,80,81]. At the same time, their aquatic larval stages have strong potential as biological control agents, actively feeding on pests such as aphids, scale insects, and other phytophagous insects, which has led to proposals for their integration into agroecological management and captive breeding programs [80,82,83]. Along the same lines, larvae of the Chironomidae family have been widely used in environmental biomonitoring due to their sensitivity to water quality, which makes them reliable bioindicators of processes such as eutrophication, organic pollution, and thermal changes, and they are widely used in both Europe and Latin America [79,84].

On the other hand, Odonata, climate change, and temperature are among the basic themes. The presence of Odonata reflects the importance of this group as a classic bioindicator in biomonitoring programs, due to its sensitivity to environmental changes, relatively short life cycles, and easy visual detection, attributes that favor its inclusion in participatory projects [53,85,86]. However, despite their potential, the systematic use of dragonflies in citizen science initiatives still seems to be underexplored. Although Odonata is among the most charismatic and easily observable groups, most of the data generated by volunteers remains scattered, unstandardized, and focused only on presence records, which limits its use for robust population and environmental analyses [87,88]. These gaps could be addressed through the implementation of standardized protocols for citizen-based monitoring, which would enhance data quality, comparability, and utility for ecological and conservation analyses. Terms such as climate change and temperature indicate a growing recognition of citizen science as a relevant tool for tracking the effects of climate change on aquatic ecosystems, using orders that are sensitive to temperature and solar radiation, such as Odonata [8,53,55].

Recent studies have shown that volunteers have contributed to monitoring phenological changes, species distribution, and extreme temperature events, particularly in temperate zones [21,89]. However, integrating this data into robust ecological assessments still faces methodological challenges, such as data heterogeneity and the scarcity of long time series in tropical regions [8,90]. Furthermore, the lack of protocols or literature to guide how monitoring should be carried out means that an opportunity to expand studies on a global scale is being missed.

In the niche topics quadrant, the terms Agriculture, Anisoptera, and Zygoptera stand out, indicating subfields with solid thematic development, although still disconnected from the central core of aquatic citizen science. The term Agriculture suggests a growing focus on the interface between agricultural practices, biological control, and aquatic insect communities, as in the case of the syrphids described in previous paragraphs. A recent study in France, which utilized citizen science data on Odonata spanning over a decade, demonstrated that intensive agricultural landscapes have a significant influence on the richness of the suborders Anisoptera and Zygoptera in pond and stream ecosystems [91].

The terms Anisoptera and Zygoptera indicate a taxonomic focus on these two suborders of Odonata, which are widely valued for their environmental sensitivity and visual appeal [23]. The explicit morphological distinction between the two suborders, as well as their contrasting ecophysiological requirements [86], combined with the ease of counting and direct observation in the field, enables lay participants to make reliable records [53]. For example, the Dragonfly Hunter CZ app allows users to identify odonates based on data such as color, habitat, and suborder, encouraging participatory records even without technical training [92]. In another initiative, the Dragonfly Mercury Project, volunteers identified dragonflies of the suborder Anisoptera with an average accuracy of 86% at the family level, demonstrating that visual recognition of these taxonomic categories is feasible even for amateurs [93]. Despite this potential, there is still limited integration of these approaches into broader participatory platforms. Studies show that many records remain fragmented, with taxonomic gaps or identification bias on the part of observers [87,88], which can compromise their full incorporation into robust ecological analyses.

In the quadrant of emerging or declining topics, the term stream macroinvertebrates appears, indicating low density and centrality in the citizen science literature for aquatic biomonitoring. Although it has historical relevance or emerging potential, its presence suggests that it is not yet consistently integrated into the participatory field. In the case of stream macroinvertebrates, this is a group that has been traditionally used in biomonitoring by the scientific community and in government programs [94]. However, its use in participatory initiatives still faces obstacles related to technical training, protocol rigor, and the required taxonomy. Projects such as the Anglers’ Riverfly Monitoring Initiative (United Kingdom) demonstrate that, despite its potential, community integration still requires further technical and institutional adaptation to become robustly consolidated [95].

3.4. Frequently Studied Insect Orders

The orders most represented in citizen science studies involving aquatic insects were Odonata (n = 66; 25.58%) and Diptera (n = 65; 25.19%), followed by Ephemeroptera (n = 28; 10.85%), Trichoptera (n = 28; 10.85%) and Plecoptera (n = 24; 9.30%). Other orders, such as Coleoptera (n = 22; 8.53%), Hemiptera (n = 12; 4.64%), Megaloptera (n = 3; 1.14%), and Lepidoptera, Neuroptera, and Hymenoptera, each with one record (0.39%), were less represented. In addition, seven records (about 2.75%) did not specify the orders used (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Distribution of insect orders is frequently studied in citizen science research as a tool in the biomonitoring of freshwater ecosystems using aquatic insects. Several studies included more than one insect order—databases: Scopus and Web of Science (2002—May 2025).

The predominance of the orders Odonata and Diptera in citizen science studies involving aquatic insects reflects the convergence of practical, ecological, and social factors. Dragonflies are easy to observe and visually identify, making them suitable for citizen participation, even by laypeople, mainly due to their aesthetic appeal and presence in accessible aquatic environments (such as streams and ponds) [55]. On the other hand, flies and mosquitoes (Diptera) have gained prominence in participatory surveillance projects, where volunteers can use apps to report breeding sites or adult specimens, contributing georeferenced data useful for epidemiological diagnostics and environmental management [76,96,97].

The orders Ephemeroptera, Trichoptera, and Plecoptera, although widely recognized as classic bioindicators of water quality [98,99], appeared with intermediate frequency in the studies analyzed. This moderate presence can be attributed to their high environmental sensitivity and widespread use in technical biomonitoring protocols [100,101]. However, identifying these groups at a more detailed taxonomic level requires specific skills, appropriate collection equipment, and access to taxonomic keys, which limits their adoption in projects with greater lay participation [102,103,104].

In contrast, orders such as Coleoptera, Hemiptera, Megaloptera, and other less frequent orders, such as Lepidoptera, Neuroptera, and Hymenoptera, appear with low representation in citizen science initiatives. This seems to be associated with the lower public visibility of these groups, the difficulty of observing them in the field (especially for larval stages or small specimens), and the absence of accessible illustrated guides that make their identification feasible for lay citizens [8,105,106,107]. In addition, these orders have a shorter tradition in participatory literature, in contrast to more visually recognizable or health-relevant groups [97].

The lack of intuitive visual guides exacerbates this situation. Although initiatives such as the Aquatic Insect Atlas, created by US universities and available at Macroinvertebrates.org, offer excellent educational resources, a wide disparity in global access to such tools still exists, directly impacting public engagement with less conspicuous orders [44,108]. However, emerging initiatives in Latin America, such as the Macrolatinos collaborative network, have sought to reduce these gaps by creating and disseminating support materials, adapted protocols, and field guides aimed at identifying aquatic macroinvertebrates in different countries in the region [109].

Overcoming these challenges requires multifaceted approaches. First, the adoption of hierarchical protocols, as proposed by Callisto et al. [110], which integrate identification by functional groups with subsequent taxonomic validation. Second, the development of culturally contextualized tools, exemplified by the success of illustrated guides featuring key regional species [111]. Third, the incorporation of accessible technologies, such as portable microscopy coupled with smartphones and taxonomic identification apps [112].

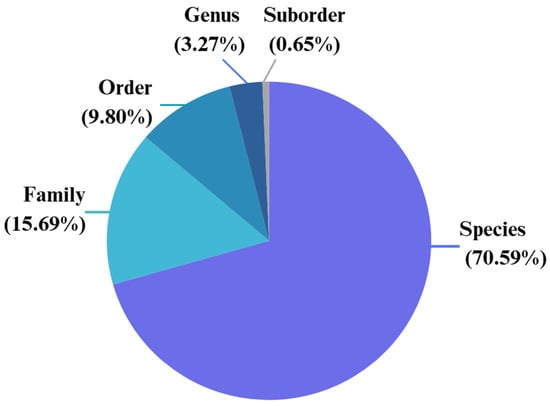

3.5. Taxonomic Levels Used in Research

The results show a marked predominance of studies using taxonomic levels of species (n = 108; 70.59%), followed by family (n = 24; 15.69%), order (n = 15; 9.80%), genus (n = 5; 3.27%), and suborder (n = 1; 0.65%) (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Taxonomic levels used in citizen science research as a tool in the biomonitoring of freshwater ecosystems using aquatic insects. Data from Scopus and Web of Science databases (2002—May 2025).

The predominance of species-level use in research indicates a trend toward greater taxonomic detail, supported by the direct involvement of specialists and the use of technologies such as iNaturalist, which integrates artificial intelligence and collaborative validation to achieve up to 98% taxonomic accuracy in observations recorded by citizens [113]. In addition, many initiatives incorporate DNA barcoding or metabarcoding, especially in groups with complex morphology or larvae, allowing identification down to the species level, even in fragmented samples or those that are difficult to differentiate visually [114]. These tools are particularly important in biodiversity-rich regions, such as the Neotropics, where taxonomic challenges are significant due to high biodiversity and a shortage of specialists [115]. However, studies warn that this acceptable resolution may reduce the role of citizen scientists, as it requires equipment, infrastructure, and technical training, restricting the applicability of participatory methodologies in regions with less technological or institutional support [114,116].

However, the predominance of species-level identification may also reflect a geographic bias associated with the maturity of scientific knowledge. Most of the studies analyzed were conducted in countries of the Global North, where biodiversity is comparatively lower and where scientific infrastructure, genetic databases, and identification guides are more consolidated, facilitating more refined taxonomic resolutions [73]. In contrast, in the Global South, particularly in tropical regions, high species richness and persistent knowledge gaps pose barriers to species-level identification [107]. Thus, in these contexts, broader taxonomic levels become not only viable but necessary to ensure the feasibility of participatory biomonitoring programs [8].

On the other hand, broader taxonomic levels such as family and order have been advocated as viable and informative alternatives for participatory biomonitoring programs [3]. For bioindicator groups like aquatic macroinvertebrates, identifications at these higher taxonomic levels may be sufficiently robust to detect ecological patterns and environmental degradation [117,118,119,120]. This approach has been adopted in initiatives such as the ICMBio Monitora Project, which employs higher taxonomic resolutions to maximize public participation and ensure data standardization without compromising diagnostic value [23]. Moreover, a scaled approach that combines species-level identification where feasible with broader classifications for taxonomically complex groups helps expand participation by reducing the need for specialized expertise, while maintaining analytical reliability [121,122].

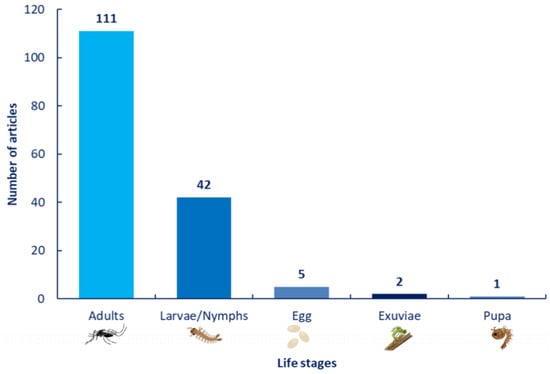

3.6. Most Researched Life Stages

The majority of the studies analyzed focused on organisms in the adult stage (n = 111; 69%), followed by the larval and nymphal stages (n = 42; 26.03%). In contrast, the egg (n = 5; 3.11%) and pupal stages (n = 1; 1.24%) were considerably less investigated. Exuviae (n = 2; 0.62%) do not represent a stage of the life cycle but were included as they are related to the type of material examined, in line with the objective of characterizing the biological focus of the studies (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Distribution of life stages and other categories used in studies on citizen science as a tool for freshwater ecosystem biomonitoring with aquatic insects. Some studies encompassed multiple life stages or developmental stages of the analyzed taxa—databases: Scopus and Web of Science (2002—May 2025).

The higher frequency of adult records in citizen science projects contrasts with the predominance of immature forms in conventional ecological studies. This pattern may stem from the greater ease of observation, visual identification, and aesthetic appeal of adults, particularly in groups such as Odonata [123]. Additionally, the use of digital platforms, which primarily rely on photographic records, favors the documentation of visible and charismatic organisms [124,125].

However, the limited inclusion of immature forms reveals a relevant methodological gap, since their presence could enrich projects with more sensitive indicators of environmental quality [34]. As discussed by Bried et al. [87], this global trend imposes at least three critical ecological limitations: (i) it reduces the capacity for early detection of impacts, as EPT larvae respond quickly to environmental changes [126]; (ii) it neglects effective bioindicators such as Chironomidae larvae, which display morphological deformities associated with metal pollution [127,128]; and (iii) it hinders the assessment of population parameters such as recruitment and reproductive success [129].

Although rarely explored in the studies analyzed, exuviae represent a promising methodological alternative, especially in citizen science initiatives. Because they do not involve the direct handling of living organisms, their collection is considered non-invasive and ethically favorable in conservation contexts [72]. Exuviae of orders such as Odonata and Chironomidae preserve diagnostic morphological traits that allow for reliable taxonomic identification [130,131]. In addition to reflecting the successful completion of the aquatic life cycle in the monitored environment, their use is also compatible with molecular approaches, such as DNA barcoding, which enables genetic analyses from non-destructive material [72,130]. Although technically more demanding, incorporating exuviae into participatory protocols may help overcome the methodological limitations of conventional photographic records, while also respecting the principles of minimal environmental impact.

3.7. Profile of Participants and Levels of Engagement

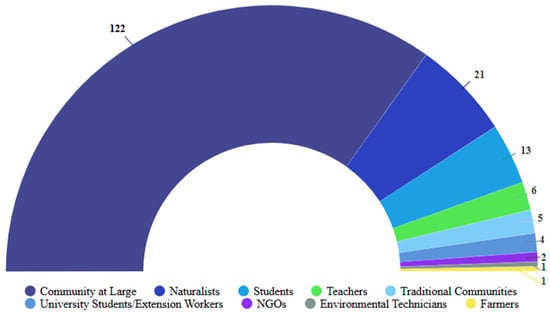

3.7.1. Profile of Participants

The analysis of the types of participants involved in citizen science projects revealed a strong predominance of the general community (n = 122; 70%), followed by naturalists (n = 21; 12%), students (n = 13; 7.01%), and teachers (n = 6; 3.43%). Traditional communities (n = 5; 2.86%), university students (n = 4; 2.29%), NGOs (n = 2; 1.14%), environmental technicians (n = 1; 0.7%), and farmers (n = 1; 0.57%) were the least represented (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Profile of participants involved in citizen science projects as a tool for freshwater ecosystem biomonitoring using aquatic insects. Several studies included more than one profile, using databases such as Scopus and Web of Science (2002—May 2025).

The study results reveal a striking scenario regarding the participants’ profiles. The general community constitutes the overwhelming majority of those involved, followed by naturalists and students. This pattern contrasts sharply with conventional biomonitoring models, in which specialized technicians have traditionally assumed the leading role [132].

A particularly relevant aspect concerns the low representation of teachers and university students, which indicates a significant opportunity to integrate these projects into formal curricular activities. This gap contrasts with European experiences, such as the Schools United for Climate Action program and projects promoted by the European Citizen Science Association (ECSA), which have linked citizen science and school curricula, contributing both to the development of scientific competencies and to students’ environmental engagement [69,133]. Successful experiences in this regard have already been documented in environmental education initiatives and participatory geoscience projects in Europe [12]. Such practices demonstrate the educational potential of citizen science, which is often underutilized in the analyzed experiences.

The predominance of participants without specialized training underscores the critical need for three fundamental elements. First, the adoption of simplified protocols, such as those developed for the participatory monitoring of Odonata [53,87], enables data collection by non-experts. Second, the use of technological support tools, such as image recognition applications (e.g., iNaturalist), which reduce taxonomic barriers and assist in accurate organism identification [134]. Ultimately, the implementation of expert validation mechanisms remains crucial to ensure data quality [135].

When analyzing the participation of specific groups, the worrying underrepresentation of traditional communities and environmental technicians becomes evident. This scenario reflects deep structural challenges, ranging from cultural barriers to the marginalization of local knowledge in relation to technical-scientific knowledge [24]. Participatory initiatives still struggle to engage with Indigenous and riverside epistemologies, despite the recognized value of traditional ecological knowledge [15,23,136].

Although this study has a global scope, its findings and patterns gain particular relevance when applied to biodiversity-rich contexts. In these territories, the active participation of local communities can expand the spatial and temporal scale of monitoring. However, the chronic shortage of specialists imposes limits on remote data validation. In this context, co-created projects emerge as promising models, as they foster greater integration between scientific and local knowledge, with long-term positive impacts on environmental conservation [31,137,138]. The inclusion of traditional communities requires specific public policies that recognize their contributions to ecological knowledge and provide incentives for their continuous participation in scientific initiatives [16]. Such policies must also address logistical, technological, and linguistic challenges that often constrain the engagement of these groups in formalized citizen science projects [20].

3.7.2. Levels of Engagement in Citizen Science

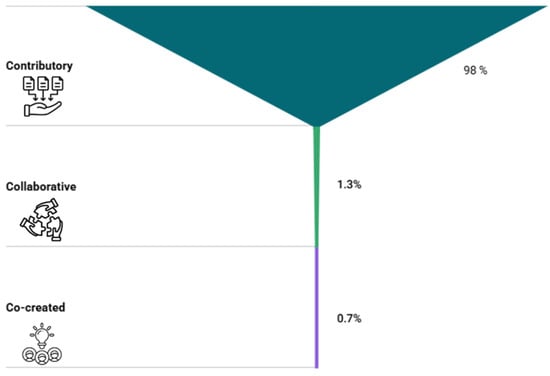

Participation in this type of initiative was, practically unanimously, at the contributory level, which predominates (n = 150; 98%), while collaborative (n = 2; 1.3%) and co-created levels (n = 1; 0.7%) remain incipient (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Distribution of levels of citizen participation (contributory, collaborative, co-created) in studies on citizen science using aquatic insects, with data from Scopus and Web of Science databases (2002—May 2025).

The results reflect a strong bias toward the contributory model in citizen science initiatives for freshwater ecosystem biomonitoring. This trend is consistent with previous studies documenting how, despite the global growth of citizen science, most projects continue to restrict public involvement to operational tasks such as data collection, without actively engaging citizens in research design, result interpretation, or environmental decision-making [45,132,139]. As noted by Tengö et al. [140], overcoming this scenario requires recognizing citizen science not merely as a tool for data gathering but as a meeting ground between distinct knowledge systems, where Indigenous and local knowledge is treated as legitimate and indispensable for socioecological management. Similarly, Serbe-Kamp et al. [141] emphasize that participatory projects only achieve an emancipatory character when they move toward collaborative and co-creative models, in which communities exercise decision-making power and governance over research processes.

A clear example of contributive projects is the Water Assessments by Volunteer Evaluators program in New York State, USA. Although the program enables volunteers to collect benthic macroinvertebrates, taxonomic identification and data analysis are centralized by a specialized technical team to ensure data quality [142]. While this approach is practical in expanding ecological observations [124,143], it tends to reproduce vertical relationships between scientists and the public, restricting the epistemic and transformative potential of citizen science [144]. Limited participation can undermine the social appropriation of the knowledge produced, weaken the link between science and territory, and even render local knowledge invisible and irrelevant to adaptive ecosystem management [145].

In contrast, collaborative and co-created models have demonstrated substantial benefits, as they strengthen mutual learning, increase the social legitimacy of results, and promote fairer and more sustainable forms of environmental governance [135,140]. In contexts of high sociocultural diversity, such as many tropical regions, these approaches enable the integration of Indigenous and community knowledge, enriching ecological understanding and fostering more environmentally contextualized decision-making [146].

However, the implementation of these deeper participatory models faces significant barriers. These include the lack of training in participatory methodologies within academic communities, the limited institutional recognition of the value of knowledge co-production, and the pressure for quantifiable and replicable results within short timeframes [147,148]. Moreover, power dynamics, rigid regulatory frameworks, and the neoliberal emphasis on the privatization and commercialization of knowledge often hinder the equitable inclusion of social actors in environmental monitoring processes [149].

The transition from contributory models to cocreated models in citizen science represents an important step forward for the consolidation of more horizontal and collaborative practices [30,32,45]. While contributory models tend to focus citizen participation on data collection, cocreated models involve participants in multiple stages of the scientific process, from the formulation of questions to the interpretation of results and decision-making [135,139]. This shift requires strategies that value the dialogue of knowledge and co-responsibility in knowledge production, such as the creation of continuous training spaces, the inclusion of community leaders in defining monitoring goals, and the use of participatory methodologies for analyzing and disseminating results [140,148]. These approaches favor not only the technical improvement of participants but also the strengthening of links between science and society, contributing to local empowerment and the sustainability of biomonitoring actions [135,140,145,146].

Given this scenario, it is necessary to promote policies and practices that acknowledge and value the diversity of ways of knowing and doing science. This includes the development of participatory facilitation capacities, the redesign of technological platforms that enable horizontal collaboration, and the establishment of ethical frameworks that guarantee the fair distribution of benefits, responsibilities, and recognition among all stakeholders [140,150]. Only in this way will it be possible to advance toward a truly transformative citizen science, capable of contributing both to scientific knowledge and to socio-environmental justice.

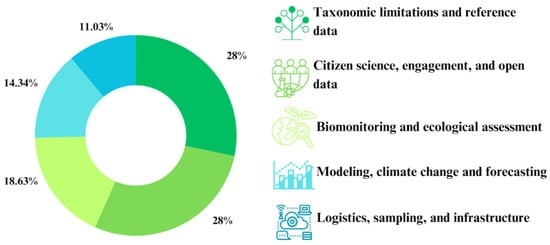

3.8. Practical and Methodological Challenges Described in the Studies

The analysis of the practical and methodological challenges described in the studies revealed a predominance of themes related to taxonomic limitations and reference data (n = 77; 28%) and citizen science, engagement, and open data (n = 77; 28%). These were followed by themes biomonitoring and ecological assessment (n = 49; 18.63%), to modeling, climate change, and forecasting (n = 39; 14.34%), and finally, logistics, sampling, and infrastructure (n = 30; 11.03%) (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Practical and methodological challenges described in studies on citizen science as a tool for freshwater ecosystem biomonitoring using aquatic insects. Several studies were included in more than one category—databases: Scopus and Web of Science (2002—May 2025).

The challenges identified in the literature reveal structural and methodological aspects that constrain the full potential of citizen science as a tool for biomonitoring with aquatic insects. The predominance of the categories “taxonomic limitations and reference data” and “modeling, climate change, and forecasting” reflects the centrality of persistent scientific and technical barriers, particularly in contexts of high biological diversity such as the tropics.

Taxonomic limitations are primarily related to the Linnean and Wallacean shortfalls, which hinder accurate identification of taxa in biodiversity-rich regions lacking specialists [65,115]. Furthermore, the scarcity of tropical genetic libraries and regional scientific collections limits the applicability of modern tools, such as DNA barcoding [73]. Studies show that citizen science platforms based on machine learning and collaborative data exhibit spatial biases, with reduced representativeness and accuracy in biodiversity-rich and undersampled regions—particularly in the tropics—due to the unequal concentration of records in temperate areas and developed economies [151,152,153].

In parallel, challenges linked to ecological modeling and climate change highlight the difficulty of integrating participatory data into more complex analyses, such as forecasting environmental impacts or evaluating future scenarios [154,155]. The spatial and temporal heterogeneity of citizen-collected data, the lack of environmental metadata, and the low interoperability with climate databases hinder the use of such data in robust predictive models [88,156,157]. This scenario reveals a gap between participatory data production and its strategic use in evidence-based environmental policymaking.

On a sociotechnical level, challenges categorized as “citizen science, engagement, and open data” point to issues related to project design. Community participation, although essential, remains limited mainly to the data collection stage, reinforcing a predominantly contributory model [30,132]. The scarce presence of collaborative or co-created models hinders the social appropriation of knowledge. It diminishes the transformative potential of citizen science as a tool for inclusion and epistemic justice [142]. In addition, the lack of accessible platforms, validated protocols, and systematic curation processes hampers the reuse and sharing of data [158,159,160].

Operational challenges, such as those categorized under “biomonitoring and ecological assessment” and “logistics, sampling, and infrastructure,” reveal recurring material and institutional constraints in initiatives conducted outside hegemonic centers of scientific production. Many projects lack standardized protocols adapted to the realities of lay participants, compromising both data comparability and their application in environmental diagnostics [161,162]. The predominance of visual records of adult organisms, for example, reflects the absence of training strategies that would allow the inclusion of larval stages—more sensitive to environmental changes but more difficult to identify [87,126].

Finally, logistical barriers such as travel costs, limited access to remote areas, and resource scarcity hinder the geographical and temporal expansion of projects, generating sampling biases that compromise the ecological robustness of analyses [163,164]. These limitations are even more pronounced in countries of the Global South, where the absence of consistent public policies and reliance on temporary grants or international cooperation render participatory projects vulnerable to discontinuity [73,165]. Moreover, researchers face disproportionate obstacles in accessing competitive funding, publishing in high-impact journals, or participating in international research networks, mainly due to the hegemony of Northern institutions in setting scientific agendas and academic recognition criteria [166]. Thus, what manifests as a lack of infrastructure or logistical difficulties in the field is, in fact, a consequence of an unequal power structure that shapes the possibilities for full participation by researchers.

4. Conclusions

This study revealed that citizen science has become established as a relevant and expanding tool for freshwater ecosystem biomonitoring, particularly using aquatic insects, in countries of the Global North. Through a comprehensive bibliometric analysis, we have evidenced a growing field, albeit one marked by epistemological, geographical, and methodological asymmetries. The concentration of initiatives in countries with consolidated scientific infrastructure, combined with the underrepresentation of biodiversity-rich tropical regions, points to an imbalance in the production and application of environmental knowledge, with direct implications for epistemic justice and conservation effectiveness.

The data indicate that projects are still structured mainly under contributory models, with little incorporation of collaborative or co-created approaches, thereby limiting participant empowerment and the transformative potential of citizen science. At the same time, persistent technical challenges—such as taxonomic shortfalls, gaps in tropical genetic databases, and barriers to the use of data in ecological modelling—limit the full integration of the generated information into robust environmental assessments.

The predominance of adults over those in immature stages, the focus on only a few taxonomic orders, and the limited use of accessible identification tools reflect a methodological gap that undermines both the ecological sensitivity of the data and the inclusion of diverse audiences. To overcome these limitations, it is urgent to strengthen multiscalar strategies that combine: (i) protocols adapted to different participant profiles, (ii) open and culturally contextualized technologies, (iii) distributed scientific validation networks, and (iv) public policies that ensure funding and institutional continuity. Platforms such as iNaturalist, Macrolatinos, and Macroinvertebrados.org exemplify multiscalar approaches by enabling citizen observations to be validated by experts, providing accessible tools for diverse users, and fostering continuous engagement across scales and communities.

More than a tool for data collection, citizen science should be conceived as a dynamic arena for collaborative knowledge creation, in which local knowledge, community experiences, and scientific expertise interact on equitable grounds. Consolidating this paradigm requires the ethical, technological, and political redesign of participatory biomonitoring programs to ensure the active inclusion of local communities, especially in territories of high biological and sociocultural diversity. By integrating open science, citizen engagement, and environmental conservation, citizen science has the potential not only to produce data but also to reshape how freshwater ecosystems are understood, valued, and protected in the twenty-first century.

5. Limitations and Future Perspectives

Although this study adopted a robust bibliometric approach, based on widely recognized databases (Scopus and Web of Science) and replicable methodologies, it is essential to acknowledge some limitations inherent to this type of analysis. The decision to restrict the search to peer-reviewed articles may have excluded relevant contributions published in book chapters, conference proceedings, or technical reports from local initiatives, particularly in regions of the Global South. In addition, despite the use of careful filters and manual review, relevant studies may have been omitted due to terminological variations or indexing errors.

Despite these limitations, the study provides a comprehensive overview of the trends, gaps, and challenges associated with the use of citizen science in biomonitoring with aquatic insects. The data systematized here can help guide future investigations and strategic interventions, with an emphasis on the geographical expansion of initiatives, the strengthening of local capacities, and the enhancement of participant engagement levels.

In terms of future perspectives, there is an urgent need to geographically expand studies to biodiversity-rich and underrepresented regions such as Latin America, Asia, and Africa. Despite their ecological and sociocultural importance, these areas remain on the margins of dominant scientific production, which limits the effectiveness of global conservation strategies and undermines equity in access to scientific information. At the same time, it is essential to broaden the taxonomic and biological scope of studies by including neglected aquatic insect orders and less-addressed life stages such as larvae and pupae, which have high bioindicator value. Overcoming this gap requires the development of illustrated regional guides, accessible methodological protocols, training workshops for citizen scientists, and culturally contextualized digital tools that enable the effective inclusion of citizens in collection and identification processes. Successful initiatives such as Macroinvertebrates.org and Macrolatinos demonstrate how open-access illustrated guides and collaborative digital platforms can strengthen local identification capacities and promote broader citizen participation in freshwater biomonitoring.

Another strategic aspect concerns the strengthening of collaborative and co-created approaches, moving beyond the predominantly contributory model identified in this study. Projects designed in a participatory manner, with the active involvement of local communities in all stages—from methodological design to data analysis and application—are essential for promoting epistemic justice, social appropriation of knowledge, and concrete impacts on territories. In this context, it is also relevant to invest in the integration of emerging technologies such as genetic barcoding, environmental DNA, predictive modeling, and portable sensors. These tools can enhance the diagnostic capacity of citizen science projects, provided they are accompanied by technical training strategies and institutional strengthening adapted to the realities of limited infrastructure.

The appreciation of traditional ecological knowledge also emerges as a crucial dimension for advancing citizen science. In Indigenous, riverside, Afro-descendant, and other local communities, cultural and historical ties to aquatic ecosystems provide a rich foundation for more rooted and effective monitoring and conservation strategies. Recognizing these epistemologies, which remain marginalized in formal scientific systems, is a decisive step toward building more sensitive, just, and place-based public policies. Furthermore, consolidating institutional frameworks and public policies that financially support citizen science is indispensable for its stability and expansion. This includes promoting participatory research through national and international funding calls, integrating citizen science into school and university curricula, creating incentives for local institutions, and granting official recognition of data generated by community projects in decision-making processes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.R., J.M.B.O.-J., M.A.G.-M., E.C.d.S. and F.A.O.; methodology, W.R., J.M.B.O.-J., M.A.G.-M., E.C.d.S. and F.A.O.; software, W.R. and F.A.O.; validation, J.M.B.O.-J. and E.C.d.S.; formal analysis, W.R., J.M.B.O.-J., M.A.G.-M. and E.C.d.S.; investigation, W.R., M.A.G.-M., F.A.O. and E.C.d.S.; data curation, W.R. and J.M.B.O.-J.; writing—original draft preparation, W.R. and J.M.B.O.-J.; writing—review and editing, W.R., J.M.B.O.-J., M.A.G.-M., E.C.d.S., K.D.-S., L.J., J.F.M.J. and H.L.N.L.; visualization, J.M.B.O.-J., M.A.G.-M., E.C.d.S., K.D.-S., L.J., J.F.M.J. and H.L.N.L.; supervision, J.M.B.O.-J.; project administration, J.M.B.O.-J. and W.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets were obtained from the Web of Science and Scopus databases, and are accessible under licensing agreements. Processed data and analysis outputs are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

W.R. is grateful to the Pós Graduação em Sociedade, Ambiente e Qualidade de Vida (PPGSAQ/UFOPA) for its academic and logistical support. J.M.B.O.-J. acknowledges the financial support from Edital No. 003/2025—PPGSAQ/UFOPA/Programa de Incentivo à Pesquisa—PIP. W.R., M.A.G.-M., F.A.O. and H.L.N.L. are grateful to the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES)—Funding Code 001 for the doctoral scholarship. E.C.d.S. is thankful to the Programa de Pós Graduação em Ecologia (PPGECO/UFPA), the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES)—Funding Code 001, and the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) for the doctoral scholarship. M.A.G.-M., F.A.O., H.L.N.L. and J.M.B.O.-J. are grateful to the Programa de Pós Graduação em Sociedade, Natureza e Desenvolvimento (PPGSND/UFOPA). L.J., K.D.-S., J.M.B.O.-J. and J.F.M.J. are grateful to CNPq for the productivity grants (processes 304710/2019-9, 311550/2023-1, 307808/2022-0 and 307906/2025-6, respectively). M.A.G.-M acknowledges the University of Algarve for making her academic mobility possible through the co-funding of the Erasmus+ Programme of the European Union, under the KA171 UALG ALLIANCES 2022–2025 initiative (2022-1-PT01-KA171-HED-000076571), coordinated by this institution. We extend our gratitude to the entire team of the Laboratório de Estudos de Impacto Ambiental (LEIA/UFOPA), who, in some way, supported this research. We also appreciate the support of the projects INCT Sínteses da Biodiversidade Amazônica (CNPq/MCTIC/INCT-2022 58/2022, process 406767/2022-0) and the Programa de Pesquisa em Biodiversidade da Amazônia Oriental-PPBIO AmOr (CNPq/MCTI/FNDCT No. 07/2023, process 441257/2023-2). We thank the Centro Avançado de Pesquisa-Ação da Conservação e Recuperação Ecossistêmica da Amazônia-CAPACREAM (Process. 444350/2024–1) for the support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Pulido-Chadid, K.; Virtanen, E.; Geldmann, J. How Effective Are Protected Areas for Reducing Threats to Biodiversity? A Systematic Review Protocol. Environ. Evid. 2023, 12, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayer, C.A.; Fernando, E.; Jimenez, R.R.; Macfarlane, N.B.W.; Rapacciuolo, G.; Böhm, M.; Brooks, T.M.; Contreras-MacBeath, T.; Cox, N.A.; Harrison, I.; et al. One-Quarter of Freshwater Fauna Threatened with Extinction. Nature 2025, 638, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, E.C.; De Azevedo, K.D.F.S.; De Carvalho, F.G.; Juen, L.; Da Rocha, T.S.; Oliveira-Junior, J.M.B. Impacts of Oil Palm Monocultures on Freshwater Ecosystems in the Amazon: A Case Study of Dragonflies and Damselflies (Insecta: Odonata). Aquat. Sci. 2025, 87, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo-Santos, V.M.; Frederico, R.G.; Fagundes, C.K.; Pompeu, P.S.; Pelicice, F.M.; Padial, A.A.; Nogueira, M.G.; Fearnside, P.M.; Lima, L.B.; Daga, V.S.; et al. Protected Areas: A Focus on Brazilian Freshwater Biodiversity. Divers. Distrib. 2019, 25, 442–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottoni, F.P.; Ândrade, M.; Henschel, E.; Azevedo-Santos, V.M.; Pavanelli, C.S.; Albert, J.S. Editorial: Freshwater Biodiversity Crisis: Multidisciplinary Approaches as Tools for Conservation Volume II. Front. Environ. Sci. 2025, 13, 1613883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization The United Nations World Water Development Report 2024: Water for Prosperity and Peace; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2024; ISBN 978-92-1-358911-3.

- Momblanch, A.; Kelkar, N.; Braulik, G.; Krishnaswamy, J.; Holman, I.P. Exploring Trade-Offs between SDGs for Indus River Dolphin Conservation and Human Water Security in the Regulated Beas River, India. Sustain. Sci. 2022, 17, 1619–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Moreno, M.A.; da Silva, E.C.; Oliveira, F.A.; Nascimento, A.C.L.; Michelan, T.S.; Dias-Silva, K.; Teodósio, M.A.; Moura, J.F., Jr.; Oliveira-Junior, J.M.B.; Juen, L. Use of Aquatic Organisms as Flagship Species in Selecting Priority Areas for Conservation. Water Biol. Secur. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabout, J.C.; Machado, K.B.; David, A.C.M.; Mendonça, L.B.G.; Silva, S.P.D.; Carvalho, P. Scientific Literature on Freshwater Ecosystem Services: Trends, Biases, and Future Directions. Hydrobiologia 2023, 850, 2485–2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClenachan, L.; Rick, T.; Thurstan, R.; Trant, A.; Alagona, P.; Alleway, H.; Armstrong, C.; Bliege Bird, R.; Rubio-Cisneros, N.; Clavero, M.; et al. Global Research Priorities for Historical Ecology to Inform Conservation. Endang. Species Res. 2024, 54, 285–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tickner, D.; Opperman, J.J.; Abell, R.; Acreman, M.; Arthington, A.H.; Bunn, S.E.; Cooke, S.J.; Dalton, J.; Darwall, W.; Edwards, G.; et al. Bending the Curve of Global Freshwater Biodiversity Loss: An Emergency Recovery Plan. BioScience 2020, 70, 330–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, S.; See, L.; Carlson, T.; Haklay, M.; Oliver, J.L.; Fraisl, D.; Mondardini, R.; Brocklehurst, M.; Shanley, L.A.; Schade, S.; et al. Citizen Science and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 922–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strayer, D.L.; Dudgeon, D. Freshwater Biodiversity Conservation: Recent Progress and Future Challenges. J. N. Am. Benthol. Soc. 2010, 29, 344–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishtiaque, A.; Masrur, A.; Rabby, Y.W.; Jerin, T.; Dewan, A. Remote Sensing-Based Research for Monitoring Progress towards SDG 15 in Bangladesh: A Review. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levis, C.; Rezende, J.S.; Barreto, J.P.L.; Barreto, S.S.; Baniwa, F.; Sateré-Mawé, C.; Zuker, F.; Alencar, A.; Mugge, M.; Simon De Moraes, R.; et al. Indigenizing Conservation Science for a Sustainable Amazon. Science 2024, 386, 1229–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cancio, A.K.C.; Guerrero-Moreno, M.A.; Da Silva, E.C.; Oliveira, F.A.; Dias-Silva, K.; Moura, J.F., Jr.; Vieira, T.A.; Calvão, L.B.; Juen, L.; Oliveira-Junior, J.M.B. The Impacts of Fire Use in the Brazilian Amazon: A Bibliometric Analysis. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2025, 34, WF24182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lameira, H.L.N.; Guerrero-Moreno, M.A.; Da Silva, E.C.; Oliveira, F.A.; Teodósio, M.A.; Dias-Silva, K.; Moura, J.F.; Juen, L.; Oliveira-Junior, J.M.B. Citizen Science as a Monitoring Tool in Aquatic Ecology: Trends, Gaps, and Future Perspectives. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trummer, J.; Wilkes-Allemann, J. The Potential of Participatory Citizen Science for Assessing Ecosystem Services in Support of Multi-Level Decision-Making—Insights from Switzerland. For. Policy Econ. 2025, 176, 103510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, Y.; Miyata, A.; Ikeuchi, U.; Nakahara, S.; Nakashima, K.; Ōnishi, H.; Osawa, T.; Ota, K.; Sato, K.; Ushijima, K.; et al. Interlinking Open Science and Community-Based Participatory Research for Socio-Environmental Issues. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2019, 39, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lameira, H.L.N.; Guerrero-Moreno, M.A.; Silva, E.C.; Santos, P.R.B.; Teodósio, M.A.; Oliveira-Junior, J.M.B. Citizen Science from the Perspective of Higher Education Professors. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Gönner, J.; Masson, T.; Köhler, S.; Fritsche, I.; Bonn, A. Citizen Science Promotes Knowledge, Skills and Collective Action to Monitor and Protect Freshwater Streams. People Nat. 2024, 6, 2357–2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gisondi, S.; Lenzi, A.; Bardiani, M.; Blandino, C.; Hardersen, S.; Maurizi, E.; Mosconi, F.; Nardi, G.; Roversi, P.F.; Campanaro, A. The Longer, the Better? Assessing the Results of an Eight-Year Citizen Science Initiative Targeting Protected Insect Species. Front. Environ. Sci. 2025, 13, 1566160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Moreno, M.A.; Juen, L.; Puig-Cabrera, M.; Teodósio, M.A.; Oliveira-Junior, J.M.B. Neotropical Dragonflies (Insecta: Odonata) as Key Organisms for Promoting Community-Based Ecotourism in a Brazilian Amazon Conservation Area. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2024, 55, e03230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, E.C.; Guerrero-Moreno, M.A.; Oliveira, F.A.; Juen, L.; De Carvalho, F.G.; Barbosa Oliveira-Junior, J.M. The Importance of Traditional Communities in Biodiversity Conservation. Biodivers. Conserv. 2025, 34, 685–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Moreno, M.A.; Oliveira-Junior, J.M.B. Approaches, Trends, and Gaps in Community-Based Ecotourism Research: A Bibliometric Analysis of Publications between 2002 and 2022. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, O.J.; Francisco Da Silva, F.; Juliani, F.; César Ferreira Motta Barbosa, L.; Vieira Nunhes, T. Bibliometric Method for Mapping the State-of-the-Art and Identifying Research Gaps and Trends in Literature: An Essential Instrument to Support the Development of Scientific Projects. In Scientometrics Recent Advances; Kunosic, S., Zerem, E., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019; ISBN 978-1-78984-712-3. [Google Scholar]

- Engel, S.R.; Voshell, J.R. Volunteer Biological Monitoring: Can It Accurately Assess the Ecological Condition of Streams? Am. Entomol. 2002, 48, 164–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walpole, S.C. Including Papers in Languages Other than English in Systematic Reviews: Important, Feasible, yet Often Omitted. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2019, 111, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aria, M.; Cuccurullo, C. Bibliometrix: An R-Tool for Comprehensive Science Mapping Analysis. J. Informetr. 2017, 11, 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonney, R.; Cooper, C.B.; Dickinson, J.; Kelling, S.; Phillips, T.; Rosenberg, K.V.; Shirk, J. Citizen Science: A Developing Tool for Expanding Science Knowledge and Scientific Literacy. BioScience 2009, 59, 977–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haklay, M. Citizen Science and Volunteered Geographic Information: Overview and Typology of Participation. In Crowdsourcing Geographic Knowledge; Sui, D., Elwood, S., Goodchild, M., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 105–122. ISBN 978-94-007-4586-5. [Google Scholar]

- Shirk, J.L.; Ballard, H.L.; Wilderman, C.C.; Phillips, T.; Wiggins, A.; Jordan, R.; McCallie, E.; Minarchek, M.; Lewenstein, B.V.; Krasny, M.E.; et al. Public Participation in Scientific Research: A Framework for Deliberate Design. Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17, art29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, D.M.; Resh, V.H. (Eds.) Freshwater Biomonitoring and Benthic Macroinvertebrates; Chapman & Hall: New York, NY, USA, 1993; ISBN 978-0-412-02251-7. [Google Scholar]

- Buss, D.F.; Carlisle, D.M.; Chon, T.-S.; Culp, J.; Harding, J.S.; Keizer-Vlek, H.E.; Robinson, W.A.; Strachan, S.; Thirion, C.; Hughes, R.M. Stream Biomonitoring Using Macroinvertebrates around the Globe: A Comparison of Large-Scale Programs. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2015, 187, 4132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerrero-Moreno, M.A.; Oliveira-Junior, J.M.B. A Global Bibliometric Analysis of the Scientific Literature on Entomotourism: Exploring Trends, Patterns and Research Gaps. Biodivers. Conserv. 2024, 33, 3929–3959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrad, C.C.; Hilchey, K.G. A Review of Citizen Science and Community-Based Environmental Monitoring: Issues and Opportunities. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2011, 176, 273–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, A.; Lynn, S.; Lintott, C. An Introduction to the Zooniverse. HCOMP 2013, 1, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesaglio, T.; Callaghan, C.T. An Overview of the History, Current Contributions and Future Outlook of iNaturalist in Australia. Wildl. Res. 2021, 48, 289–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynn, S.J.; Kaplan, N.; Newman, S.; Scarpino, R.; Newman, G. Designing a Platform for Ethical Citizen Science: A Case Study of CitSci.Org. Citiz. Sci. Theory Pract. 2019, 4, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raddick, M.J.; Prather, E.E.; Wallace, C.S. Galaxy Zoo: Science Content Knowledge of Citizen Scientists. Public Underst. Sci. 2019, 28, 636–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]