1. Introduction

In the Anthropocene era, interactions between humans and wildlife are increasingly inevitable [

1] as a result of various factors, such as the transformation and fragmentation of natural habitats [

2], population growth and technological advancements [

3], climate change, the recovery and reintroduction of species [

4], and the increasing demand for nature tourism [

5]. As a result, the literature on human–wildlife conflict, interaction, and coexistence has expanded rapidly, reflecting the growing importance of understanding these dynamics in contemporary conservation efforts [

6].

This phenomenon has also been observed in the marine environment. Marine industrialization processes, which include maritime transport, seismic surveys, the installation of offshore wind farms, tourism, aquaculture, recreational fishing and other fishing activities, increase human activity at sea and thus also increase the number of interactions that occur with ocean fauna [

7,

8]. Studies that have investigated this topic have reported an increase in interactions between humans and various species of marine animals, such as pinnipeds [

9], cetaceans [

10], sharks [

11] and turtles [

12].

In recent years, interactions involving a small group of orcas (

Orcinus orca) have received considerable interest from the public. Orcas, commonly known as orcas or killer whales, is a cosmopolitan apex predator belonging to the family Delphinidae. As the largest oceanic dolphins, these marine mammals are distributed throughout all the world’s oceans [

13]. They display varied social behaviors, from breaches and spy-hops to playing with objects and engaging in socio-sexual displays. Their communication combines echolocation and pod-specific calls, with some shared repertoires that maintain cohesion and reduce inbreeding risk [

14].

The group of orcas involved in the interactions consists of fewer than 50 individuals, which exhibit distinct characteristics compared to other groups of killer whales in the Northeast Atlantic [

15]. This population is commonly located in the Strait of Gibraltar and the Gulf of Cádiz, although they move along the Atlantic coast of the Iberian Peninsula following the migrations of their main source of food, i.e., bluefin tuna [

16]. The study of molecular markers, ecological indicators, and photo-identification data indicates that these whales are a distinct group within the same species, separate from other populations in the Northeast Atlantic [

15].

Starting in 2020, some individuals of this group of Iberian killer whales began to approach boats while they were sailing and to ram them on the hull or at the helm [

17]. These events have taken place in the Strait of Gibraltar and, subsequently, along the Portuguese coast and in Galicia. These interactions have been repeated, and the number of encounters between killer whales and sailboats or small pleasure boats has come to exceed half a thousand. Some of these events have caused significant damage to such vessels, mainly due to breakage and disablement of the rudder; however, on a very small number of occasions, such incidents have caused these vessels to sink [

18].

This behavior is unprecedented among orcas, and the scientific community has not provided a definitive explanation of the factors that motivate these mammals to interact with boats. Three main hypotheses have been proposed in this context. On the one hand, the origin of this behavior may be related to cetaceans’ past traumatic experiences, such as being struck by a boat or seeing the hit against another animal [

19]. A second explanation posits that the boats could act as play stimuli that orcas use to develop the motor, cognitive and cooperative skills that they use in their hunting activities [

20]. A third hypothesis proposes that the emergence of this behavior among killer whales could be the result of a combination of various factors, such as the stress generated by increased maritime traffic in their habitat, the competition with the fisheries for tuna and the reduced availability of prey. Finally, the fact that orcas are animals that have the ability to learn and reproduce behaviors based on the experiences of others cannot be overlooked; thus, mutual influence and learning due to social interaction are relevant elements of orcas’ behavior that should also be taken into consideration in this context [

15].

Investigations of the factors that drive Iberian killer whales to interact with vessels reveal that this situation entails a potential danger for navigation in the Strait of Gibraltar and the Atlantic coast of the Iberian Peninsula, even though there is no record of humans being attacked by orcas in their natural habitat. This concern is further highlighted in Martel’s research, which includes surveys and interviews with sailors and other stakeholders that revealed sharp contrasts in perceptions and responses to the Iberian orca–vessel interactions [

21]. Sailors overwhelmingly framed the encounters as problematic, with 38% describing them as “attacks,” and most expressed negative emotions such as fear or anxiety. Safety was their dominant concern (87%), but many also worried about orca welfare (85%). Nearly all reported behavioral changes, including altered navigation routes, avoidance of affected waters, or the use of deterrents. By contrast, other stakeholders—such as researchers, fishers, whale-watch operators, and marina staff—more often characterized the issue as minor or “not a concern”. This divergence underscores that the phenomenon is not only ecological but also a social conflict, driven by mismatched risk perceptions, emotional responses, and differing priorities among user groups.

In this context, it is important to highlight the fact that the news concerning environmental issues disseminated by media outlets has a significant influence on public’s opinion regarding such interactions between humans and wildlife [

22]. In this way, media coverage that emphasizes the anecdotal and particular aspects of these interactions can help spread a reductionist vision of the various relationships of mutual dependence among different species that coexist within an ecosystem [

23]; furthermore, this interpretation can influence environmental policies pertaining to the species involved [

24]. Similarly, the disproportionate informational attention that negative incidents involving wild animals receive (in comparison with encounters that do not lead to such consequences) can distort people’s perceptions of the real frequency of harmful interactions between humans and wildlife [

17]. In addition, when information regarding such conflicting interactions between humans and animals is deficient or incomplete, this situation can facilitate the spread of feelings of fear and misconceptions regarding the species involved in these interactions, thus helping fuel the conflict itself [

25]. However, the media can also help promote positive views of the relationship between humans and wildlife, particularly by highlighting the roles that such species play in the process of shaping people’s well-being on the basis of the services that they provide within the ecosystem and disclosing responsible coexistence practices [

26,

27].

Therefore, the task of analyzing the information that the media disseminates regarding the unusual behavior on the part of Iberian killer whales is relevant since it allows us to investigate the processes by which public opinion is formed. This aspect influences the management efforts made by administrations responsible for the conservation of this species, which is included in the Red List of Threatened Species of the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources and is classified as vulnerable in the Spanish Catalogue of Threatened Species (CEEA) [

28]. In accordance with this general purpose, the specific objective of this study is to analyze the information concerning interactions between Iberian killer whales and recreational vessels. This analysis will focus on news items available in the Spanish press and digital media from June 2022 to September 2024.

3. Results

The section on the results of this research is divided into three parts. First, an analysis of the level of agreement observed between the evaluators who analyzed the news items included in the sample is presented. Subsequently, the results of an analysis of the six variables included in this research are presented. Finally, a synthesis of the results obtained from an analysis of the news is provided.

3.1. Analysis of the Level of Agreement Between Human Coders

The analysis of the level of agreement between the two evaluators regarding the 26 categories associated with the 6 variables under study in this research, revealed Krippendorff alpha values that ranged from 0.850 to 0.990. These results indicate a high level of agreement between the two evaluators. The results of a concordance analysis are available in the

Supplementary Materials for this article (see

File S3).

3.2. Analysis of the Proportion of News by Category for Each Variable

3.2.1. Variable 1: Event Details

In the sample under analysis in this context, 89.7% of the articles (N = 96) offered information concerning at least one of the categories associated with this variable, which was related to the details of the encounters between orcas and vessels. In addition, among the entire set of articles, 25.2% (N = 27) addressed only one category, whereas 51.4% (N = 55) presented data concerning two or three categories. Finally, 13.1% (N = 14) provided information regarding four or more categories.

With respect to specific information concerning the characteristics of the events associated with Iberian killer whales, 70.1% of the news items (N = 75) mentioned the type of vessel involved. Such a mention could be included in a general way, such as by indicating whether these vessels were sailboats or pleasure boats or by specifying their length. In addition, 57.9% of the informative articles under investigation (N = 62) offered some geographical reference regarding the place or places at which the events occurred, 43% (N = 46) indicated the damage that the killer whales caused to the boats, and 32.7% (N = 35) offered an account of the events that occurred. Only 10.3% of the news (N = 11) offered data regarding the behavior of the killer whales involved in this context (for example, how they approached the boats or how different individuals acted) or a residual number of news reports concerning the speed of the boats.

3.2.2. Variable 2: Explanations of the Behavior of Killer Whales

A total of 43% of the news items under analysis (N = 46) mentioned at least one possible cause of the behavior of these Iberian killer whales. Among all the news items under investigation, 14% (N = 15) presented a single explanation, whereas 29% (N = 31) addressed two or more possible causes of the behavior of these cetaceans.

In relation to the explanations referenced in the articles under analysis in this context, the behavior of the killer whales could be related to the curiosity of these mammals or to some type of playful activity in which the youngest members of this species engaged. These points were mentioned in 32.7% of the articles (N = 35). Allusions to incidents, accidents or traumas that killer whales could have suffered in their past interactions with boats as a possible cause of the behavior of these cetaceans appeared in 23.4% of the news items (N = 25).

In addition, references to orcas’ learning ability, their communication skills or the social bonds they tend to establish within the group were made in 23.4% of the informative pieces (N = 25). Finally, two informative pieces referred to the pressure or stress generated by a combination of factors.

3.2.3. Variable 3: Preventative Actions

A total of 47.7% of the news items under analysis (N = 51) mentioned at least one solution to the problem caused by encounters between killer whales and boats. Among the total set of news items, 31.8% (N = 34) presented a single solution to the problem caused by the unusual behavior of the Iberian killer whales, whereas 15.9% (N = 17) mentioned two or more possible solutions.

In terms of the type of solution mentioned in the articles, 32.7% of the news items included in this research (N = 35) provided specific information regarding the behavior of people with responsibility for the boats that could help mitigate or prevent encounters with orcas. Strategies related to consideration of the area and the speed of navigation, the type of navigation (motorized or sailing), the most appropriate schedules for avoiding killer whales and the actions that should be taken in the event of a collision were highlighted.

A total of 14% of the news items (N = 15) referred to technical solutions that could be used either to change the behavior of the killer whales (for example, through sound devices or accessory elements located at the helm) or to monitor cetaceans and provide information to vessels regarding the location of these animals.

In addition, 8.4% of the news items (N = 9) referred to regulatory solutions, legal changes or the implementation of prohibitions related to navigation. A similar number of informative pieces (7.5%, N = 8) highlighted the need to perform scientific investigations that could facilitate the improvement of our current state of knowledge of the behavior of killer whales. Finally, 3 articles indicated solutions that were related to the economic field, specifically with regard to the contracting of insurance to cover the risks paced by the boats, and a single news item referred to improvements in the habitat of the killer whales that should be considered as a possible solution to these challenges.

3.2.4. Variable 4: Threats Towards the Iberian Killer Whale

A total of 23.4% of the news under analysis in this context (N = 25) referred to at least one threat to Iberian killer whales. In the news as a whole, 6.5% of the articles under examination (N = 7) mentioned a single threat, whereas 16.8% of these news items (N = 18) alluded to 2 or more threats faced by orcas in the text.

Regarding the types of threats to orcas that were mentioned in the articles, 18.7% of the news items (N = 20) addressed problems related to alterations of the habitats of these mammals, including by highlighting factors such as pollution and the accumulation of waste, marine overexploitation or the effects of climate change. In addition, the maritime traffic in the routes frequented by these killer whales, the resulting collisions with boats or the noise pollution generated by naval activity were mentioned by similar numbers of news items (16.8%, N = 18). Finally, other types of additions, such as attacks on killer whales, including by shooting, or the low reproduction rate observed in this species, were mentioned by fewer articles (11.2%, N = 12).

3.2.5. Variable 5: Legal Status of the Iberian Killer Whale

A total of 26.2% of the news items under analysis in this context (N = 28) included information regarding at least one of the categories that pertained to the protection status of Iberian killer whales. Among the total news items, 16.8% (N = 18) covered a single category, whereas 9.3% presented two or more references (N = 10).

Regarding the type of information provided in this context, 19.6% of the articles (N = 21) included general references to the status of the killer whale as a threatened, vulnerable or endangered species, albeit without identifying specific regulations or agreements. In addition, 12.1% of the news items (N = 13) mentioned some of the norms or regulations that protect this species, such as the Conservation Plan of the Orcas of the Strait and Gulf of Cádiz, which was established in the Orden APM/427/2017 [

28]. Finally, seven articles indicated that Iberian killer whales are included in the Red List of Threatened Species of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, although no news items referred to international conventions.

3.2.6. Variable 6: Information Sources

A total of 81.3% of the news items included in the sample (N = 87) referred to at least one source of information in the text. A total of 55.1% of the total number of these news items (N = 59) had a single reference, whereas 26.2% (N = 28) presented two or more references.

Regarding the sources of information cited in the articles, 62.6% (N = 67) included references to authorities, who were either professionals linked to universities or experts from organizations that were dedicated to the tasks of researching and conserving marine biodiversity, such as the Coordinator for the Study of Marine Mammals (CEMMA) or the Society for the Study and Conservation of Marine Fauna (AMBAR). In addition, 29% of the news items (N = 31) mentioned some institution or public body, such as the Ministry of Transport, the Ministry for the Ecological Transition and the Demographic Challenge, the Maritime Rescue Coordination Centre or the General Directorate of Merchant Marine, in the text. This final category also includes references to international organizations that focus on the conservation and study of marine habitats, such as the International Whaling Commission or the Whale and Dolphin Conservation. The testimonies of fishermen as well as crew members of sailboats or pleasure boats were included in 12.1% of the news items (N = 13), whereas 6.5% of these articles referred to private companies (N = 7).

3.3. Summary of Results

A summary of the most significant trends identified in the analysis of the articles included in the sample is provided below.

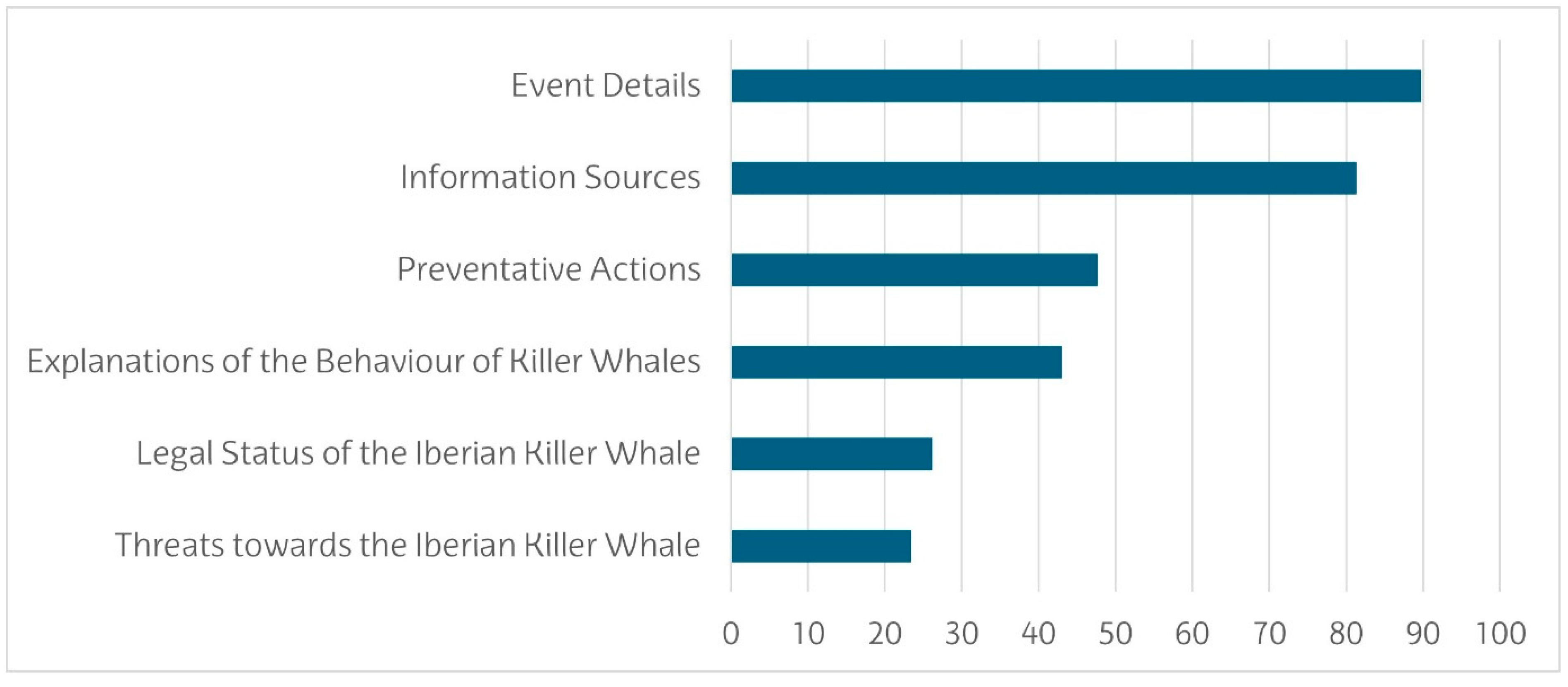

Figure 1 summarizes the frequencies of news items that included at least one reference to some of the categories associated with each variable.

First, the information regarding the details of the incidents caused by Iberian killer whales was presented in 9 out of ten news items, thus accounting for most of the sample. The articles usually addressed several relevant aspects of these events; thus, 70% of the articles mentioned more than one of the six informative categories associated with this variable. In this context, the type of vessel involved, the geographical location of the event, and the damage caused by the attack were notable.

Second, a high proportion of the news items included in this research also included references to specialized sources. In 8 out of 10 cases, the texts in question cited members of research groups, academics or professionals who had experience in the field of marine biology; alternatively, they referred to public institutions and state bodies. The testimonies of people who were involved in these incidents involving killer whales were less common.

A third notable trend in this context pertains to the fact that three out of four articles in the sample did not offer any information regarding threats to the survival of the Iberian killer whale population. A significant minority of these sources provided information regarding conservation regulations and legal protection that affect orca populations, such as international conventions or the legal frameworks operative in Spain, Morocco or Portugal, as well as references to the vulnerability of this species (such as references to its inclusion in the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species or allusions to its status as a protected species). In contexts in which these news items did include information in this regard, the majority referred to general comments concerning the risks faced by this species.

Fourth, it is important to note that information related to the explanations that the scientific community provides regarding the causes of orcas’ interactions with vessels was not predominant in the set of news items under investigation in this context. In fact, only 2 out of 5 news stories addressed this topic, and among the articles that did so, a third referred only to a single explanation.

Finally, the fact that the number of news items that addressed any of the solutions or procedures proposed in this context regarding the situation resulting from the behavior of Iberian killer whales did not include half the sample must be taken into account. In addition, two-thirds of the news reports that presented this information focused on a single type of solution. The most frequently mentioned solutions were, first, individual actions that should be considered to prevent orca encounters or mitigate their consequences and, second, the use of technological devices in this context. News items that highlighted the need to promote scientific research into the behavior of these cetaceans were in the minority, whereas references to solutions that pertained to the improvement of the habitat of orcas were exceptional.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

The killer whale (

Orcinus orca) is an oceanic predator that occupies the upper levels of the food web and plays a fundamental role in regulating the populations of its prey. In this way, it indirectly influences the structure of the food web as well as the dynamics and biodiversity of the marine ecosystem, thus helping maintain the health of the ocean [

20].

Since May 2020, a population of killer whales that habitually inhabit the Strait of Gibraltar and the Atlantic waters of the Iberian Peninsula have begun to interact with pleasure boats in unusual ways; furthermore, this behavior represents a significant challenge to maritime safety [

15]. This population, which is known as the Iberian orca, has been declared a critically endangered species and included in the Red List of Threatened Species of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature [

40]; furthermore, a plan for the conservation of this species has been approved by the government of Spain [

28].

The objective of this study is to analyze the ways in which media outlets have covered this behavior on the part of Iberian killer whales precisely because the information that these outlets disseminate contributes to the emergence of a state of opinion that ultimately influences management policies of conflicts generated by fauna in their habitat [

25].

The results of this study indicate that the details of the incidents caused by killer whales, such as the types of vessels involved, the locations at which the events occurred, the damage caused and the number of incidents, constitute the majority of the information reported in the news under examination in this research. However, information regarding the vulnerability of this species and the threats faced by these cetaceans lies very far from the informative objective of most of the articles under analysis. In addition, preventative actions that could address the challenges emerging from the behavior of Iberian killer whales usually focus on the guidelines that the people with responsibility for the boats must follow to prevent encounters with these cetaceans. However, mentions of more global actions, such as studies of the behavior of cetaceans or strategies aimed at modifying habitat-related variables that could influence the unusual behavior of orcas, are relegated to a minority of the informational pieces analyzed in this context.

These observations indicate that the information concerning the sample analyzed in this research was rooted in a mostly episodic approach that focused on particular situations, specific incidents or personal aspects of the problems at hand [

22]. Thus, a significant proportion of the news under study in this context focused on narrating the events and specific circumstances associated with the behavior of the cetaceans. These news items have thus failed to offer elements that can help the reader contextualize the behavior of the population of Iberian killer whales within a broader framework, thereby addressing the possible causes of such behavior and its relationships with other factors that transcend an isolated event.

These trends are in line with the results of previous research on this topic, which has indicated a low frequency of news reports concerning the inclusion of marine species on the IUCN Red List or their consideration of vulnerable species; in addition, news items have tended to omit the context of problems in the marine environment, instead by focusing on conjunctural aspects [

41]. In fact, the episodic approach to information tends to be predominant in the media pertaining to a wide variety of topics [

42] as well as in the context of media coverage of human-human interactions involving wildlife [

22].

Importantly, episodic approaches to wildlife information can elicit emotional reactions that negatively affect readers’ attitudes towards wildlife [

42]. In addition, these approaches tend to promote an individualistic vision of the solutions that are necessary to manage animals in their habitats instead of focusing on more global solutions that address social and institutional aspects of this situation [

43].

Another relevant observation revealed by the results of this study pertains to the fact that few articles have identified more than one possible explanation that of the behavior of orcas that has been proposed by the scientific community (for a review of these explanations, see the works of López and Methion [

20] and Esteban and co-authors [

15]). This fact makes it difficult to communicate the uncertainty that characterizes the study of the behavior of these cetaceans adequately. However, importantly, information pertaining to scientific knowledge cannot be limited to the dissemination of new discoveries but must also include references to the methods that have been used to generate those discoveries, including their limitations and uncertainties [

44]. In this way, the omission of communication regarding uncertainty, either by minimizing the unknown or by underestimating the preliminary nature of knowledge in this context, can give rise to perceptions of inconsistency, inaccuracy or a lack of transparency about the information at hand [

45].

Finally, references to specialized sources of marine biodiversity or allusions to institutions that are responsible for managing navigation or the marine environment account for a high proportion of the informative pieces included in the sample investigated in this research. The inclusion of external sources in the text of such news items with the goal of validating relevant aspects of scientific knowledge is in line with the guidelines established in the list of good practices in the context of scientific journalism [

46].

The results presented in this context should be considered considering the limitations of this study. First, it is necessary to note that this study draws exclusively on Spanish-language media and therefore reflects a Spain-centered perspective on Iberian orca–boat encounters. Including Portuguese and Moroccan outlets would help build a more complete picture of regional media responses to Iberian killer-whale behavior. Additionally, future studies should monitor whether interactions between orcas from other Northeast Atlantic subpopulations and recreational boats begin to occur; if so, analyzing media from those countries would allow comparison of framing and public reactions to orca–boat interactions across the wider region.

A second limitation is that this study examines the sample of news items as a whole. Future researchers should consider analyzing such news items by categories as well as grouping them according to the medium in which they were published, their length or the date of their publication. This approach could help identify trends in the information concerning interactions with wildlife that are not revealed by the present study.

Finally, the fact that the subject of the news under analysis in this context, which focused on various incidents associated with Iberian killer whales, is a phenomenon that remains in development must be taken into account. Therefore, it is necessary to conduct additional research to explore how the possible evolution of the behavior of killer whales is reflected in such written information. In addition, it is essential to consider the explanations of this behavior that have been provided by the scientific community as well as the vulnerable state of this species and the conservation measures that have been proposed in this context.