Effect of Silicon Formulation on Protecting and Boosting Faba Bean Growth Under Herbicide Damage

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

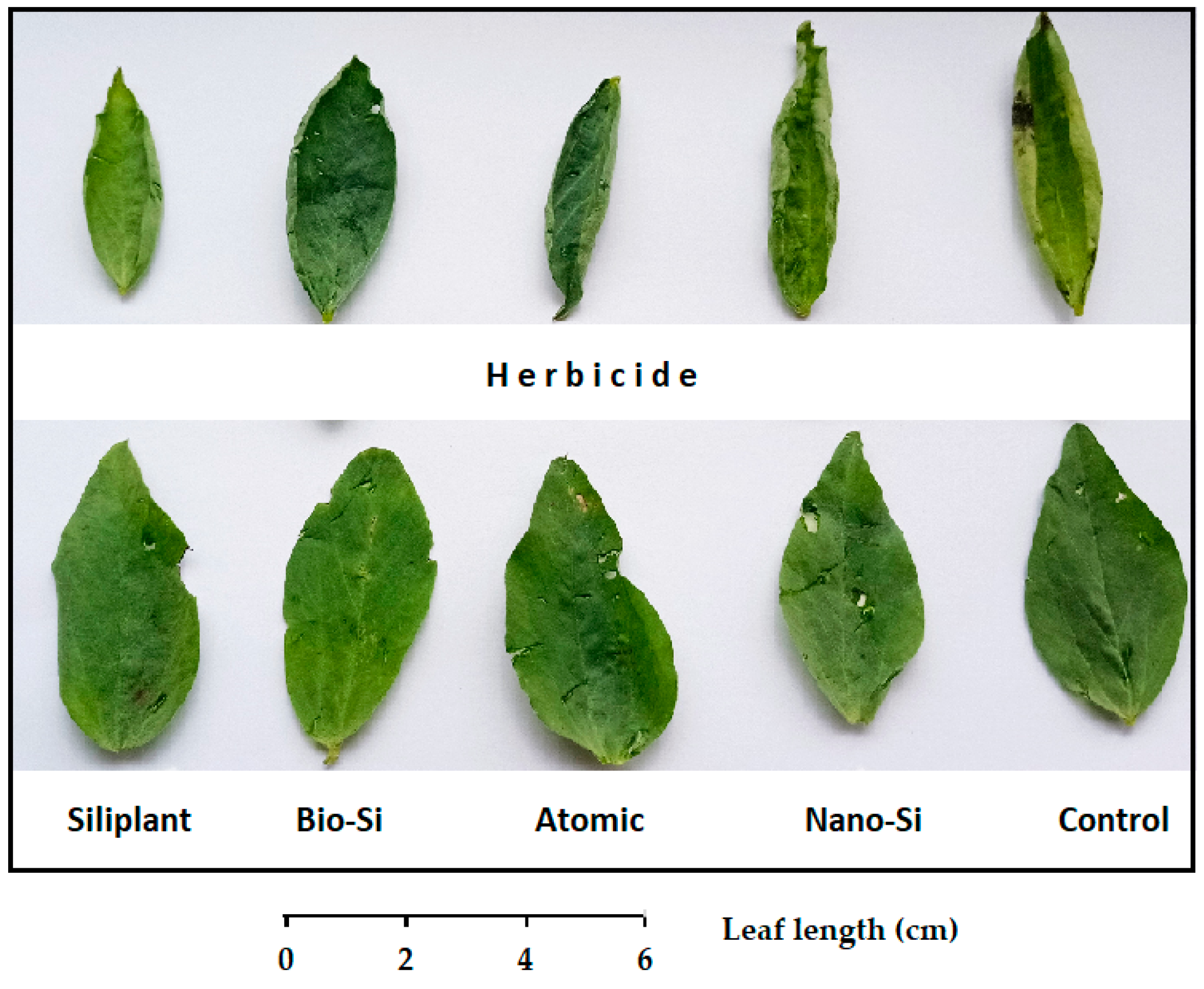

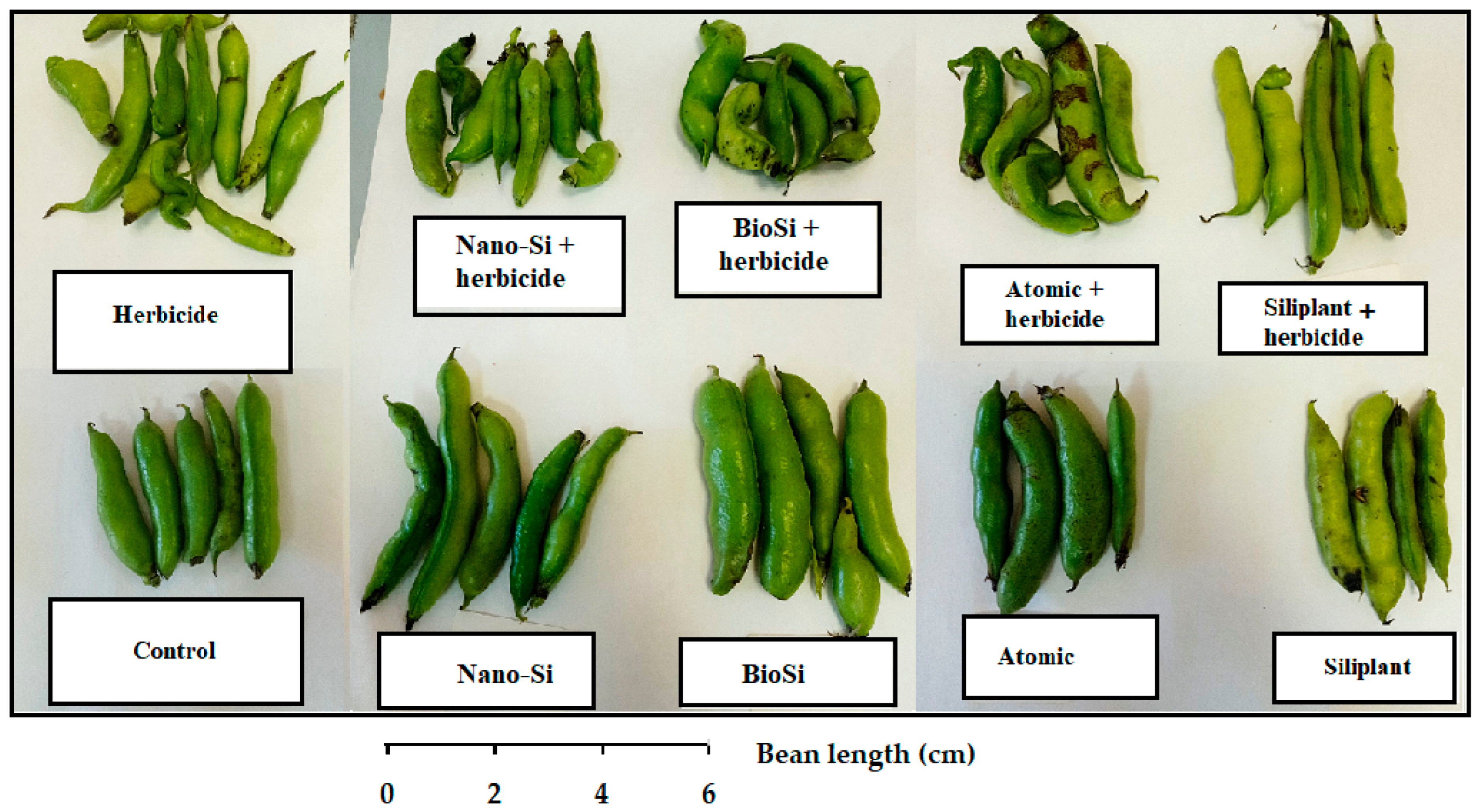

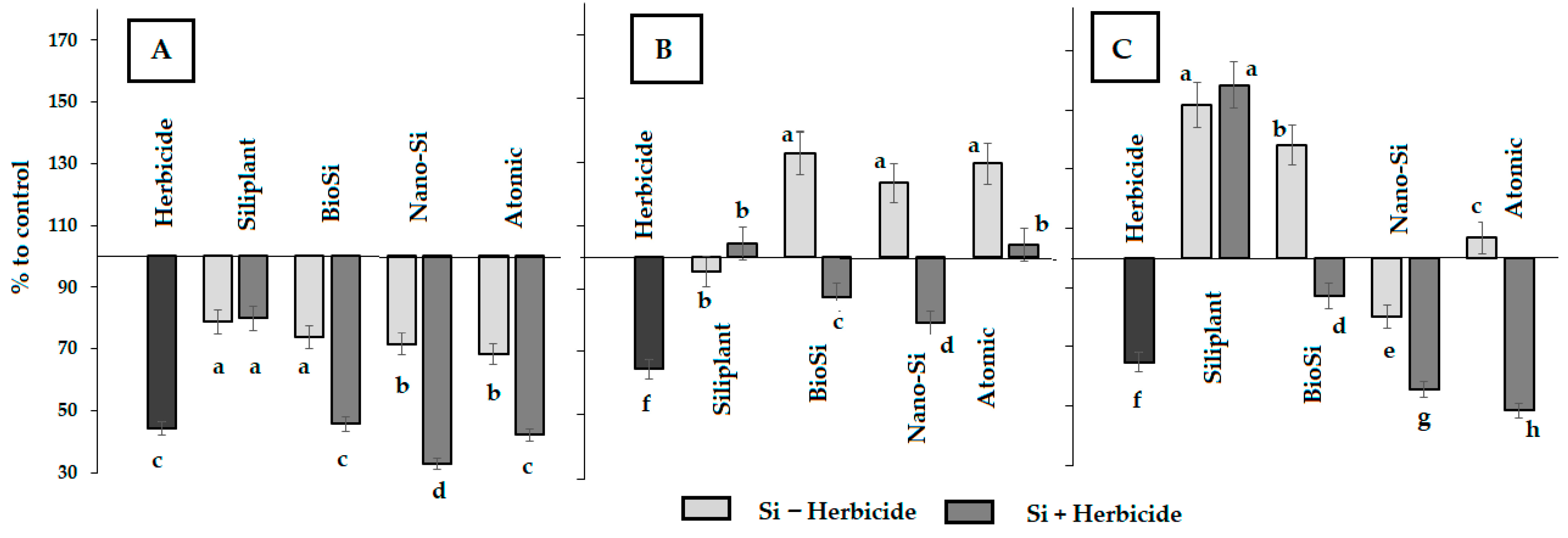

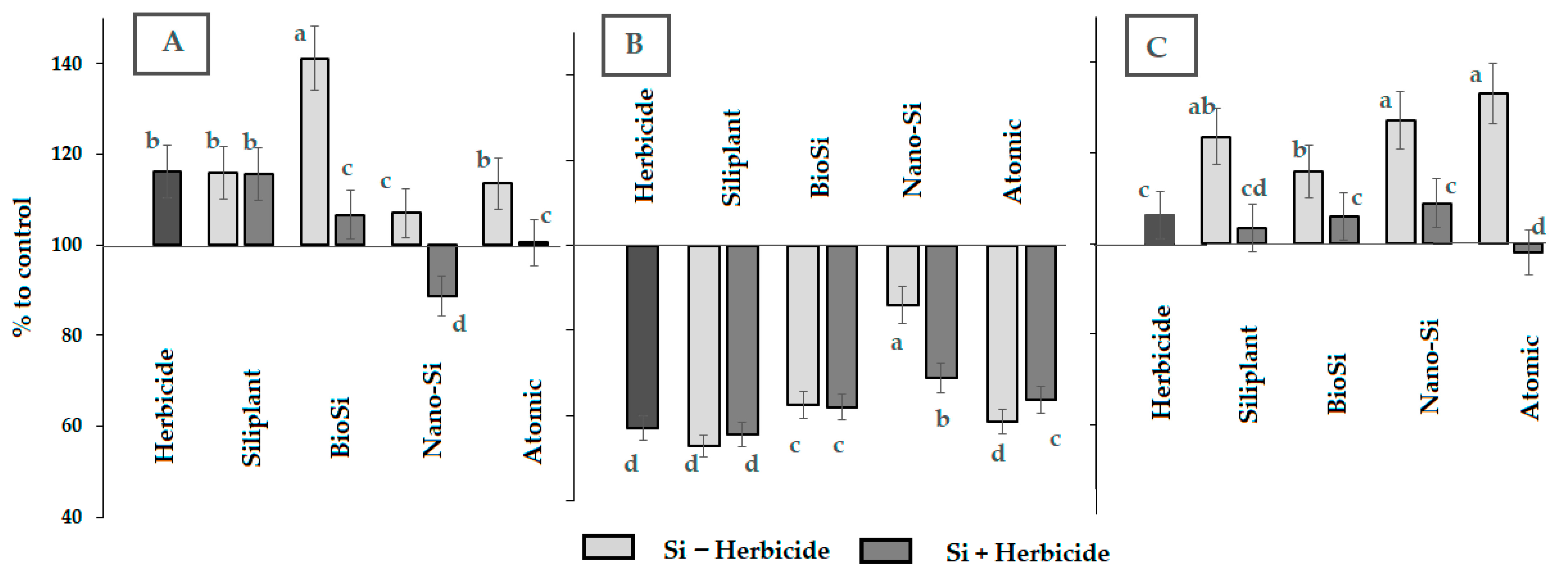

2.1. Plant Morphology

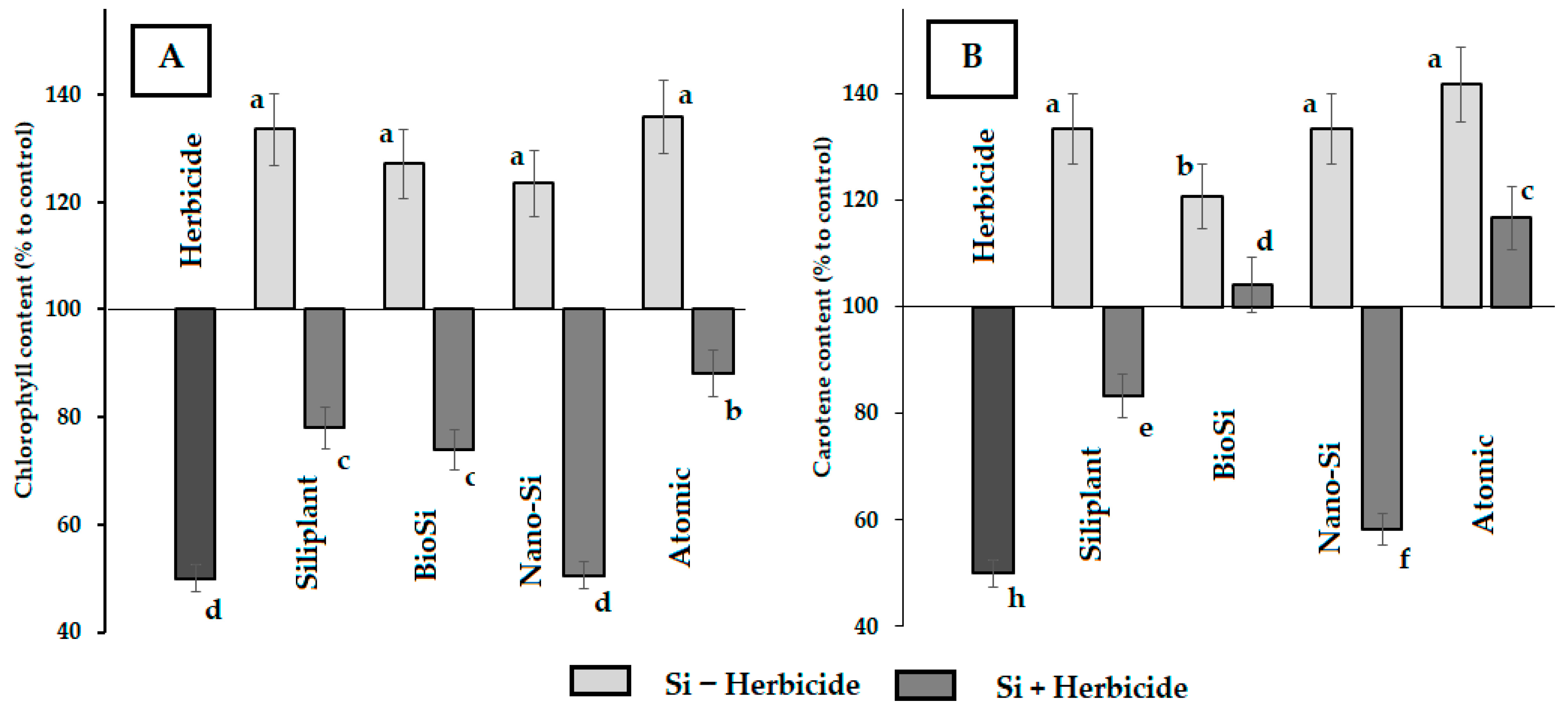

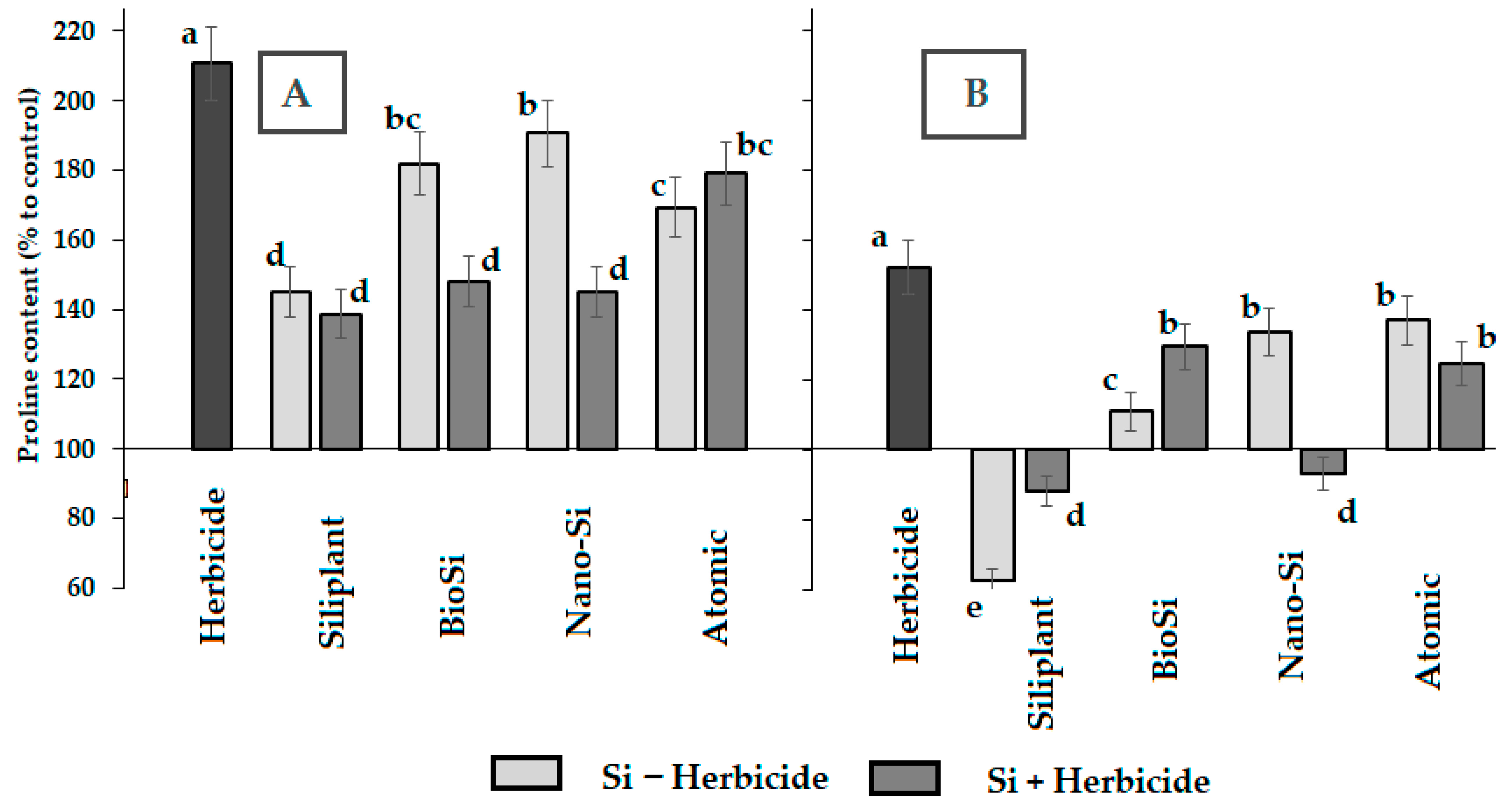

2.2. Photosynthetic Pigments and Antioxidant Status

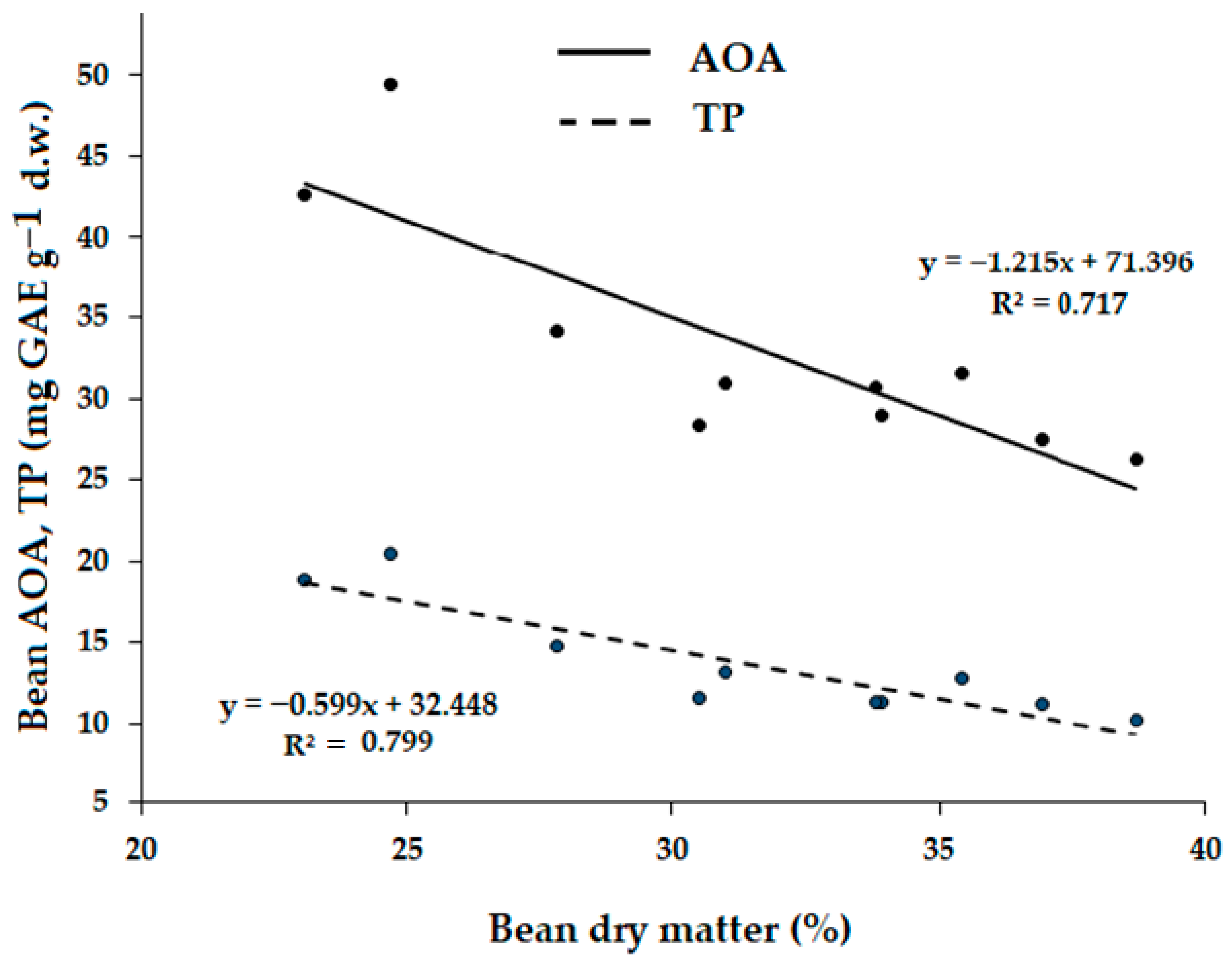

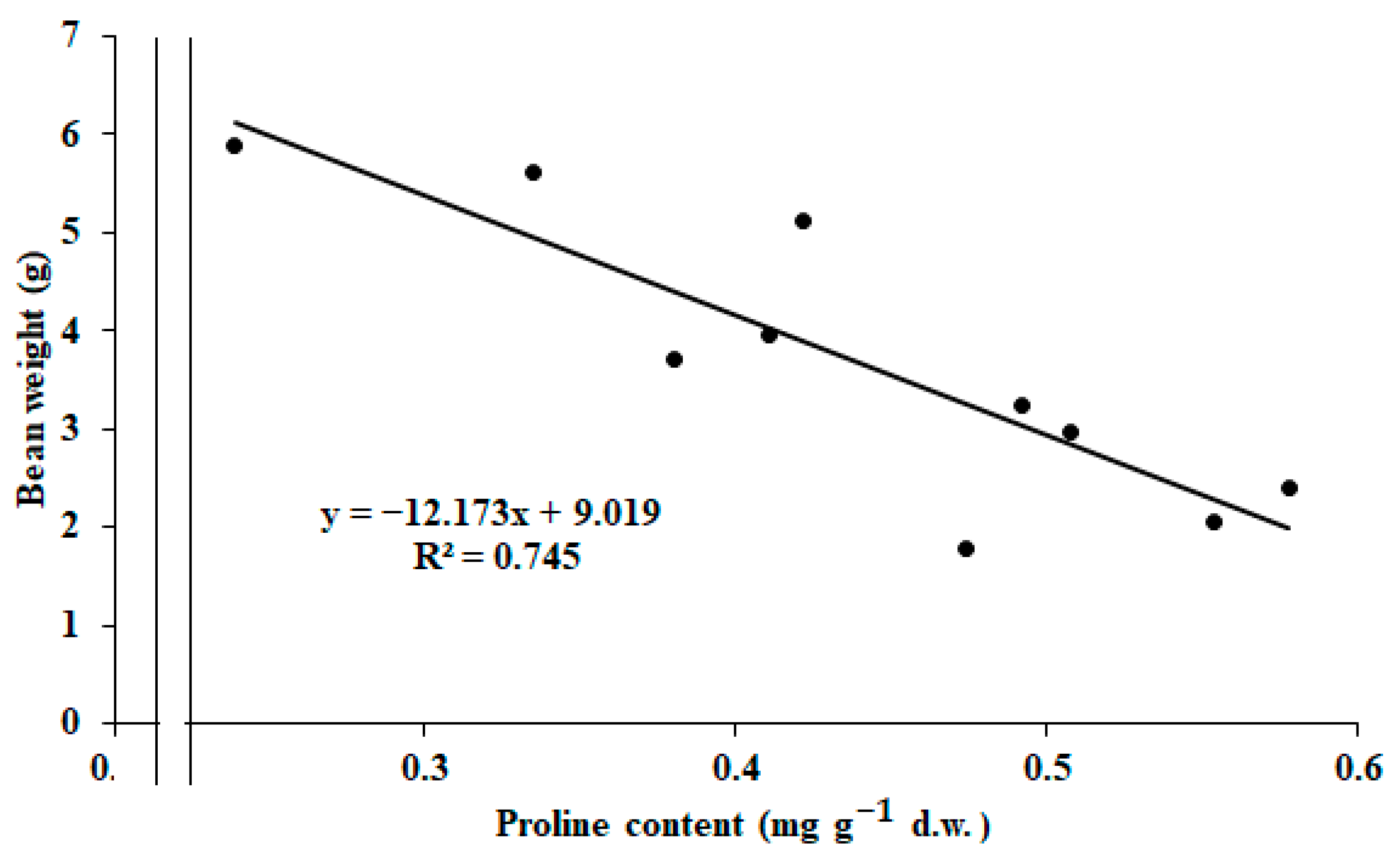

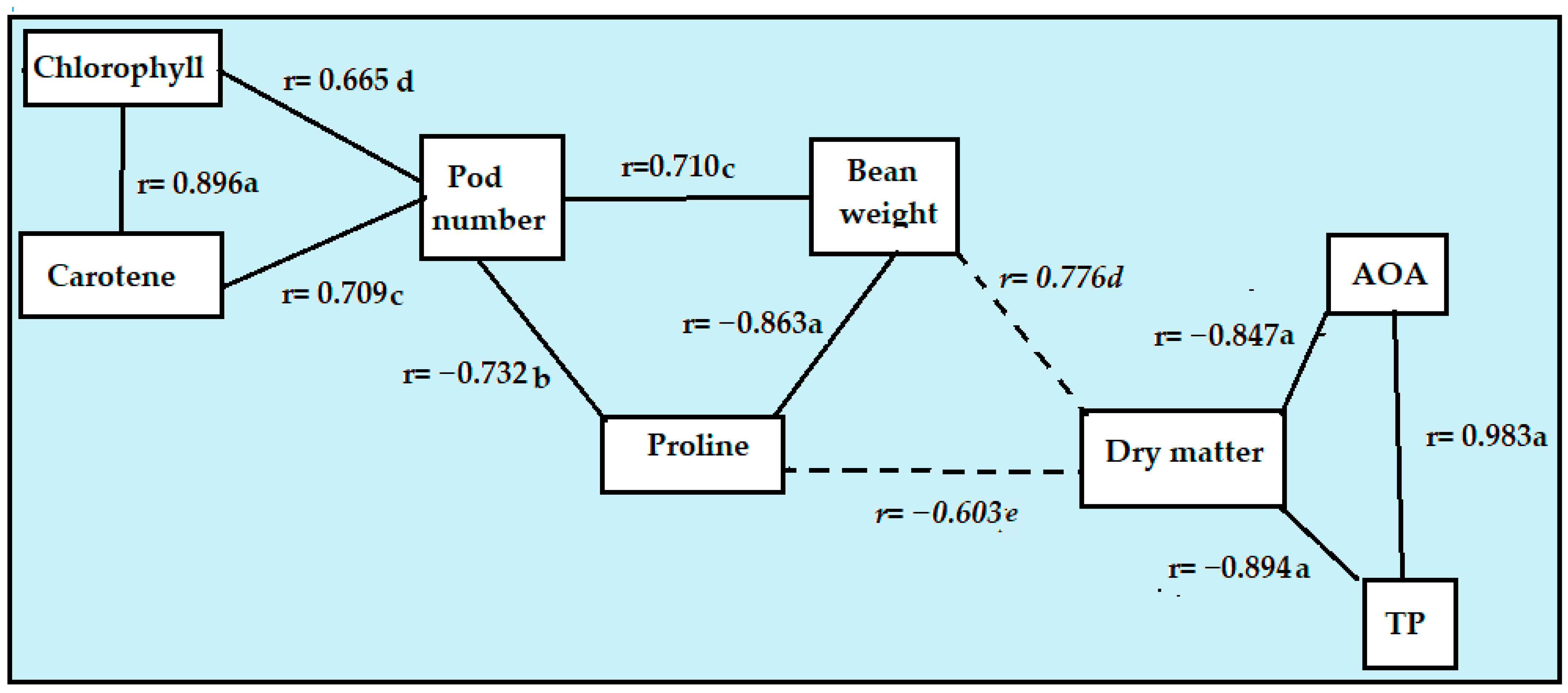

2.3. Correlations Between the Measured Parameters

3. Material and Methods

3.1. Growing Conditions and Experimental Protocol

3.2. Production of Colloidal Solution of Silicon Nanoparticles

3.3. Photosynthetic Pigments

3.4. Ascorbic Acid

3.5. Preparation of Ethanolic Extracts

3.6. Total Polyphenols (TP)

3.7. Antioxidant Activity (AOA)

3.8. Proline

3.9. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aldhahi, H.H.K.; Almtarfi, H.I.; Al-Sarraji, A.J. Evaluation of the effect of some herbicides on Vicia faba L. growth traits. J. Res. Ecol. 2018, 6, 1808–1813. [Google Scholar]

- El-Mergawi, R.; El-Dabaa, M.; Elkhawaga, F. Effect of splitting the sub-lethal dose of glyphosate on plant growth shikimate pathway-related metabolites and antioxidant status in faba beans. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 10792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burul, F.; Batic, K.; Lakic, J.; Milanovic, A. Herbicides effects on symbiotic nitrogen-fixing bacteria. J. Central Eur. Agric. 2022, 23, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, G.; Kohls, S.; Landesberg, E.; Souza, K.S.-O.; Yamda, T.; Römheld, V. Relevance of glyphosate transfer to non-target plants via the rhizosphere. J. Plant Dis. Prot. 2006, 20, 963–969. [Google Scholar]

- Kanissery, R.; Gairhe, B.; Kadyampakeni, D.; Batuman, O.; Alferez, F. Glyphosate: Its Environmental Persistence and Impact on Crop Health and Nutrition. Plants 2019, 8, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, J.P.A.R.; Teixeira, M.M.; Coury, J.R.; Ferreira, L.R. Evaluation of strategies to reduce pesticide spray drift. Planta Daninha 2003, 21, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simón, L.A.Y.; Viciedo, D.O.; Carbonari, C.A.; Duke, S.O.; de Carvalho, L.B. Silicon Treatment on Sorghum Plants Prior to Glyphosate Spraying: Effects on Growth, Nutrition, and Metabolism. Agriengineering 2024, 6, 3538–3552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bott, S.; Tesfamariam, T.; Candan, H.; Cakmak, I.; Römheld, V.; Neumann, G. Glyphosate induced impairment of plant growth and micronutrient status in glyphosate-resistant soybean (Glycine max L.). Plant Soil 2008, 312, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, L.A.C.; Carvalho, F.P.; Franca, A.C.; Francino, D.M.T.; Pinto, N.A.V.D.; Freitas, A.F. Leaf morphoanatomy and biochemical variation on coffee cultivars under drift simulation of glyphosate. Planta Daninha 2018, 36, e018143560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, T.C.G.T.; Bacha, A.L.; Camargo, B.M.; Carvalho, L.B. Influence of phosphorus fertilization on the response of pinus genotypes to glyphosate sub doses. New For. 2022, 53, 143–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, R.T.; Albrecht, A.J.P.; Albrecht, L.P.; Lorenzety, J.B.; Danilussi, M.T.Y.; Silva, R.M.; Silva, A.F.M.; Barroso, A.A.M. Soybean injury caused by the application of sub doses of 2,4-D or dicamba, in simulated drift. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part B 2023, 58, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zampiroli, R.; Cunha, J.; Alvarenga, C.B. Simulated drift of dicamba and glyphosate on coffee crop. Plants 2023, 12, 3525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, N.R.; Chaudhary, J.R.; Tripathi, A.; Joshi, N.; Padhan, B.; Yadav, S.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, R. Breeding for herbicide tolerance in crops: A review. Res. J. Biotech. 2020, 15, 154–162. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, S.; Shi, J.; Li, X.; Yang, M.; Li, C.; Zhang, D.; Yang, S.; Mei, C.; Luo, Z.; Zhang, L.; et al. Development and Breeding of Herbicide-Resistant Sorghum for Effective Cereal—Legume Intercropping. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, 2503083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abou-Khater, L.; Maalouf, F.; Jighly, A.; Alsamman, A.M.; Rubiales, D.; Rispail, N.; Hu, J.; Ma, Y.; Balech, R.; Hamwieh, A.; et al. Genomic regions associated with herbicide tolerance in a worldwide faba bean (Vicia faba L.) collection. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, M.; Zelaya, I.A. Herbicide-resistant crop and weed resistance to herbicides. Pest Manag. Sci. 2005, 61, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jan, S.; Singh, R.; Bhardwaj, R.; Ahmad, P.; Kapoor, D. Plant growth regulators: A sustainable approach to combat pesticide toxicity. 3 Biotech. 2020, 10, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Choudhary, A.; Kaur, H.; Singh, K.; Guha, S.; Choudhary, D.R.; Sonkar, A.; Mehta, S.; Husen, A. Exploring the role of silicon in enhancing sustainable plant growth, defense system, environmental stress mitigation and management. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2025, 7, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostofa, M.G.; Rahman, M.M.; Ansary, M.M.U.; Keya, S.S.; Abdelrahman, M.; Miah, M.G.; Phan Tran, L.S. Silicon in mitigation of abiotic stress-induced oxidative damage in plants. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2021, 41, 918–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golubkina, N.; Zayachkovsky, V.; Sheshnitsan, S.; Skrypnik, L.; Antoshkina, M.; Smirnova, A.; Fedotov, M.; Caruso, G. Prospects of the Application of Garlic Extracts and Selenium and Silicon Compounds for Plant Protection against Herbivorous Pests: A Review. Agriculture 2022, 12, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laane, H.M. The Effects of Foliar Sprays with Different Silicon compounds. Plants 2018, 7, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.G.; de Amorim Cordeiro, R.; das Mercês, J.K.R. Silicon can attenuate glyphosate-induced stress in young Handroanthus albus by improving photosynthetic efficiency and decreasing cellular electrolyte leakage. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 23077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaili, S.; Tavallali, V.; Amiri, B.; Bazrafshan, F.; Sharafzadeh, S. Foliar application of nano-silicon complexes on growth, oxidative damage and bioactive compounds of feverfew under drought stress. Silicon 2022, 14, 10245–10256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zargar, S.M.; Mahajan, R.; Bhat, J.A.; Nazir, M.; Deshmukh, R. Role of silicon in plant stress tolerance: Opportunities to achieve a sustainable cropping system. 3 Biotech. 2019, 9, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, A.L. Silicon: A valuable soil element for improving plant growth and CO2 sequestration. J. Adv. Res. 2025, 71, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Artyszak, A. Effect of Silicon Fertilization on Crop Yield Quantity and Quality—A Literature Review in Europe. Plants 2018, 7, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Luo, S.; Dawuda, M.M.; Gao, X.; Wang, S.; Xie, J.; Tang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Wu, Y.; Jin, L.; et al. Exogenous silicon enhances the systemic defense of cucumber leaves and roots against CA-induced autotoxicity stress by regulating the ascorbate-glutathione cycle and photosystem II. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 227, 112879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, L.M.; Soliman, M.I.; Abd El-Aziz, M.H.; Abdel-Aziz, H.M. Impact of silica ions and nano silica on growth and productivity of pea plants under salinity stress. Plants 2022, 11, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golubkina, N.; Moldovan, A.; Fedotov, M.; Kekina, H.; Kharchenko, V.; Folmanis, G.; Alpatov, A.; Caruso, G. Iodine and Selenium Biofortification of Chervil Plants Treated with Silicon Nanoparticles. Plants 2021, 10, 2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrylov, A. Application of a wetting agent ‘Atomic’ in the protection of pear plantation. Sci. Herit. J. 2021, 68, 9–12. [Google Scholar]

- Carneiro, J.M.T.; Oliveira, L.A.; Rossete, A.L.R.M.; Abreu, J.C.H.; Bendassolli, J.A. Accumulation and translocation of silicon in rice and bean plants using the 30SI stable isotope. Plant Nutr. 2010, 33, 1374–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.F.; Yamaji, N. Silicon uptake and accumulation in higher plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2006, 11, 392–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaasawi, I.S.; Khaliq, A.; Lahmod, N.R.; Matloob, A. Weed management in broad bean (Vicia faba L.) through allelopathic Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench residues and reduced rate of a pre-plant herbicide. Allelopathy J. 2013, 32, 203–212. [Google Scholar]

- Kardoni, F.; Mosavi, S.J.S.; Parande, S.; Torbaghan, M.E. Effect of salinity stress and silicon application on yield and component yield of faba bean (Vicia faba). Int. J. Agric. Crop Sci. 2013, 6, 814–818. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, M.A.; Wani, A.H.; Mir, S.H.; Rehman, I.U.; Tahir, I.; Ahmad, P.; Rashid, I. Elucidating the role of silicon in drought stress tolerance in plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 165, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, P.; Kumar, V.; Sharma, A. Interaction of silicon with cell wall components in plants: A review. J. Appl. Nat. Sci. 2023, 15, 480–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shumary, A.M.J. The role of foliar zinc application on growth and yield of faba bean varieties. Int. J. Agricult. Stat. Sci. 2020, 16, 1157–1161. Available online: https://connectjournals.com/03899.2020.16.1157 (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Al-Yasari, M.N.H.; Al-Mosawi, A.N.A.; Al-Karhi, M.A.J. Response of three faba bean cultivars to boron. Biochem. Cell. Arch. 2022, 22, 3899–3904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hujayri, J.K.O. Effectiveness of iron and manganese foliar treatments in enhancing growth and yield traits in broad bean plants (Vicia faba L.). Int. J. Plant Pathol. Microbiol. 2025, 5, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Yu, M.; Du, H.; Hu, C.; Wu, S.; Tan, Q.; Hu, X.; Shabala, S.; Sun, X. Effects of molybdenum supply on microbial diversity and mineral nutrient availability in the rhizosphere soil of broad bean (Vicia faba L.). Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2023, 205, 108203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellal, F.A.; Abdelhamid, M.T.; Abo-Basha, D.M.; Zewainy, R.M. Alleviation Of The Adverse Effects Of Soil Salinity Stress By Foliar Application Of Silicon On Faba bean (Vica faba L.). J. Appl. Sci. Res. 2012, 8, 4428–4433. [Google Scholar]

- Roggenbuck, F.C.; Pener, D. Mode of action of organosilicone adjuvants. Acta Hortic. 2000, 527, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazaralian, S.; Majd, A.; Irian, S.; Najafi, F.; Ghahremaninejad, F.; Landberg, T.; Greger, M. Comparison of silicon nanoparticles and silicate treatments in fenugreek. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 115, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, P.; Mathur, J.; Srivastava, N. Silica nanoparticles as novel sustainable approach for plant growth and crop protection. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desoky, E.-S.M.; Mansour, E.; El-Sobky, E.-S.E.A.; Abdul-Hamid, M.I.; Taha, T.F.; Elakkad, H.A.; Arnaout, S.M.A.I.; Eid, R.S.M.; El-Tarabily, K.A.; Yasin, M.A.T. Physio-Biochemical and Agronomic Responses of Faba Beans to Exogenously Applied Nano-Silicon Under Drought Stress Conditions. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 637783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, S.; Mumtaz, M.; Manzoor, S.; Shuxian, L.; Ahmed, I.; Skalicky, M.; Brestic, M.; Rastogi, A.; Ilhassan, Z.; Shafiq, I.; et al. Foliar application of silicon improves growth of soybean by enhancing carbon metabolism under shading conditions. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 159, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gad, N.; Elrahman, E.A.A.; Fekry Ali, M.E.; Abou-Shlell, M.K.; Teiba, I.I.; Almutairi, M.H.; Youse, A.F. Role and importance of cobalt in faba bean through rationalization of its nitrogen fertilization. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullin, C.A.; Fine, J.D.; Reynolds, R.D.; Frazier, M.T. Toxicological Risks of Agrochemical Spray Adjuvants: Organosilicone Surfactants May Not Be Safe. Front. Public Health 2016, 4, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arteaga, S.; Yabor, L.; Díez, M.J.; Prohens, J.; Boscaiu, M.; Vicente, O. The Use of Proline in Screening for Tolerance to Drought and Salinity in Common Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) Genotypes. Agronomy 2020, 10, 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yan, X.; Li, X.; Chen, T.U. Environmental Residues of Organosiloxane-Based Adjuvants and Its Environmental Risks for Use as Agrochemical Adjuvants. Sci. Agric. Sin. 2024, 57, 142–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Xiang, Y.; Wu, L.; Fu, S.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Y. Degradation kinetics and ecological effects of organosilicon spray adjuvants in water, maize, and wheat. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2025, 147, 108032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouraoui, M.; Abbes, Z.; L’taief, B.; Alshaharni, M.O.; Abdi, N.; Hachana, A.; Sifi, B. Exploring the biochemical dynamics in faba bean (Vicia faba L. minor) in response to Orobanche foetida Poir. parasitism under inoculation with different rhizobia strains. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0304673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limón-Pacheco, J.; Gonsebatt, M.E. The role of antioxidants and antioxidant-related enzymes in protective responses to environmentally induced oxidative stress. Mutat. Res. Genet. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen. 2009, 674, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meena, M.; Divyanshu, K.; Kumar, S.; Swapnil, P.; Zehra, A.; Shukla, V.; Yadav, M.; Upadhyay, R.S. Regulation of L-proline biosynthesis, signal transduction, transport, accumulation and its vital role in plants during variable environmental conditions. Heliyon 2019, 5, e02952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ould Said, C.; Boulahia, K.; Eid, M.A.M.; Rady, M.M.; Djebbar, R.; Abrous-Belbachir, O. Exogenously Used Proline Offers Potent Antioxidative and Osmoprotective Strategies to Re-balance Growth and Physio-biochemical Attributes in Herbicide-Stressed Trigonella foenum-graecum. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2021, 21, 3254–3268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, S.; Rani, S.; Shafi, S.; Zaffar, A.; Riyaz, I.; Wani, M.A.; Zargar, S.M.; Prasad, P.V.V.; Sofi, P.A. Pod physical traits significantly implicate shattering response of pods in beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). Biol. Plant. 2024, 68, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apolinar, A.B.; González-de la Vara, L.E.; Ramírez-Pimentel, J.G.; Aguirre-Mancilla, C.L.; Iturriaga, G.; Covarrubias-Prieto, J.; Raya-Pérez, J.C. Silicon induces changes in the antioxidant system of millet cultivated in drought and salinity. Chil. J. Agric. Res. 2021, 81, 655–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenthaler, H.K. Chlorophylls and carotenoids: Pigments of photosynthetic bio-membranes. Methods Enzymol. 1987, 148, 350–382. [Google Scholar]

- Association Official Analytical Chemists. The Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International; 22 ‘Vitamin C’; AOAC: Rockville, MD, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Golubkina, N.A.; Kekina, H.G.; Molchanova, A.V.; Antoshkina, M.S.; Nadezhkin, S.M.; Soldatenko, A.V. Antioxidants of Plants and Methods of Their Determination; Infra-M: Moscow, Russia, 2020; pp. 145–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ábrahám, E.; Hourton-Cabassa, C.; Erdei, L.; Szabados, L. Methods for determination of proline in plants. In Plant Stress Tolerance. Methods in Molecular Biology (Methods and Protocols); Sunkar, R., Ed.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2010; Volume 639, Chapter 20; pp. 317–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment | Pod Length (mm) | Seed Number per Pod | Pod Weight (g) | Seed Weight (g) | Pod Width (mm) | Pod/Seed Weight Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 69.0 ± 6.1 b | 4.75 ± 0.45 a | 5.53 ± 0.52 b | 3.70 ± 0.36 b | 16.8 ± 1.3 bc | 1.49 ± 1.20 b |

| herbicide | 61.3 ± 6.0 b | 2.10 ± 0.20 c | 3.56 ± 0.33 d | 2.40 ± 0.22 cd | 16.6 ± 1.3 c | 1.49 ± 1.20 b |

| Siliplant | 85.8 ± 8.0 a | 3.75 ± 0.34 b | 5.27 ± 0.50 b | 5.62 ± 0.56 a | 15.0 ± 1.2 c | 1.00 ± 0.10 c |

| Siliplant + H | 100.2 ± 10.0 a | 3.80 ± 0.36 b | 5.76 ± 0.54 b | 5.88 ± 0.56 a | 15.6 ± 1.2 c | 0.98 ± 0.09 c |

| BioSi | 93.8 ± 9.0 a | 3.50 ± 0.32 b | 7.34 ± 0.73 a | 5.11 ± 0.50 a | 23.5 ± 2.0 a | 1.43 ± 0.12 b |

| BioSi + H | 82.5 ± 8.0 a | 2.17 ± 0.20 c | 4.83 ± 0.44 bc | 3.23 ± 0.32 c | 19.6 ± 1.8 b | 1.49 ± 0.12 b |

| Nano-Si | 89.6 ± 8.2 a | 3.40 ± 0.31 b | 6.82 ± 0.55 a | 2.97 ± 0.27 c | 18.4 ± 1.7 b | 2.30 ± 0.20 a |

| Nano-Si + H | 69.3 ± 6.3 b | 2.56 ± 0.22 d | 4.37 ± 0.41 c | 2.06 ± 0.20 de | 17.0 ± 1.6 bc | 2.12 ± 0.20 a |

| Atomic | 88.0 ± 8.2 a | 3.25 ± 0.30 b | 7.17 ± 0.70 a | 3.95 ± 0.37 b | 18.5 ± 1.7 b | 1.45 ± 0.12 b |

| Atomic + H | 83.2 ± 8.0 a | 2.00 ± 0.20 c | 5.74 ± 0.55 b | 1.80 ± 0.17 e | 18.6 ± 2.7 b | 1.89 ± 0.17 a |

| Treatment | Chl a | Chl b | Total Chl | Carotene | Chl a/ Chl b | Chl/ Carotene | Ascorbic Acid |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 1.35 ± 0.10 b | 0.83 ± 0.08 a | 2.18 ± 0.20 b | 0.24 ± 0.02 cd | 1.63 | 9.08 | 125.4 ± 10.7 a |

| herbicide | 0.60 ± 0.06 d | 0.45 ± 0.04 c | 1.05 ± 0.10 e | 0.12 ± 0.01 e | 1.33 | 8.75 | 92.1 ± 8.9 b |

| Siliplant | 1.83 ± 0.14 a | 1.08 ± 0.10 a | 2.91 ± 0.24 a | 0.32 ± 0.03 a | 1.69 | 9.09 | 130.0 ± 10.5 a |

| Siliplant + H | 1.03± 0.10 c | 0.67 ± 0.06 b | 1.70 ± 0.14 cd | 0.20 ± 0.02 d | 1.54 | 8.50 | 102.0 ± 9.4 b |

| BioSi | 1.72 ± 0.14 a | 1.05 ± 0.10 a | 2.77 ± 0.23 a | 0.29 ± 0.03 ab | 1.64 | 7.08 | 107.8 ± 9.8 ab |

| BioSi + H | 0.96 ± 0.09 c | 0.65 ± 0.06 b | 1.61 ± 0.14 d | 0.25 ± 0.02 bc | 1.48 | 5.55 | 95.3 ± 9.0 b |

| Nano-Si | 1.69 ± 0.13 a | 1.00 ± 0.09 a | 2.69 ± 0.23 a | 0.32 ± 0.03 a | 1.69 | 8.41 | 128.5 ± 10.5 a |

| Nano-Si + H | 0.61 ± 0.06 d | 0.49 ± 0.04 c | 1.10 ± 0.10 e | 0.14 ± 0.01 e | 1.23 | 7.82 | 105.7 ± 9.7 b |

| Atomic | 1.87 ± 0.15 a | 1.09 ± 0.10 a | 2.96 ± 0.26 a | 0.34 ± 0.03 a | 1.72 | 8.70 | 110.7 ± 10.0 ab |

| Atomic + H | 1.05 ± 0.09 c | 0.87 ± 0.08 a | 1.92 ± 0.16 bc | 0.28 ± 0.03 ab | 1.72 | 8.46 | 106.7 ± 9.9 b |

| Treatment | Dry Matter | AOA | TP | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leaves | Seeds | Pod Valves | Leaves | Seeds | Pod Valves | Leaves | Seeds | Pod Valves | |

| Control | 20.0 ± 2.0 a | 24.7 ± 2.1 c | 16.0 ± 1.3 a | 81.5 ± 8.0 b | 49.5 ± 4.7 a | 88.6 ± 8.2 a | 26.6 ± 2.4 bc | 20.4 ± 1.9 a | 28.6 ± 2.7 a |

| herbicide | 17.9 ± 1.5 a | 30.5 ± 2.9 b | 17.0 ± 1.5 a | 94.7 ± 9.2 b | 28.3 ± 2.6 bc | 94.2 ± 9.1 a | 28.4 ± 2.6 ab | 11.6 ± 1.1 c | 30.6 ± 2.7 a |

| Siliplant | 21.8 ± 2.0 a | 38.7 ± 3.5 a | 17.9 ± 1.5 a | 94.5 ± 9.1 b | 26.2 ± 2.4 c | 109.5 ± 10.0 a | 23.1 ± 2.0 c | 10.2 ± 1.0 c | 29.3 ± 2.7 a |

| Siliplant + herbicide | 17.8 ± 1.5 a | 36.9 ± 3.3 a | 17.2 ± 1.4 a | 94.2 ± 9.1 b | 27.5 ± 2.5 c | 91.6 ± 9.0 ab | 27.9 ± 2.5 ab | 11.2 ± 1.0 c | 26.7 ± 2.5 ab |

| BioSi | 20.3 ± 1.9 a | 31.0 ± 2.9 b | 16.6 ± 1.4 a | 115.0 ± 10.0 a | 30.9 ± 2.9 b | 102.6 ± 10.0 a | 33.0 ± 3.1 a | 13.1 ± 1.1 b | 28.8 ± 2.7 ab |

| BioSi + herbicide | 19.8 ± 1.7 a | 33.8 ± 3.0 ab | 17.1 ± 1.4 a | 86.9 ± 8.4 b | 30.7 ± 2.9 b | 93.8 ± 9.1 a | 25.5 ± 2.4 bc | 11.3 ± 1.0 c | 30.2 ± 2.8 a |

| Nano-Si | 21.0 ± 2.0 a | 23.1 ± 2.0 c | 14.6 ± 1.2 b | 87.2 ± 8.5 b | 42.6 ± 4.0 a | 112.6 ± 10.0 a | 28.5 ± 2.6 a | 18.8 ± 1.6 a | 26.9 ± 2.5 ab |

| Nano-Si + herbicide | 18.0 ± 1.5 a | 27.8 ± 2.5 cb | 17.1 ± 1.4 a | 72.3 ± 7.0 c | 34.1 ± 3.1 b | 96.5 ± 9.2 a | 23.7 ± 2.1 b | 14.7 ± 1.2 b | 27.5 ±2.5 ab |

| Atomic | 21.1 ± 2.0 a | 33.9 ± 3.1 ab | 15.8 ± 1.3 b | 92.6 ± 9.0 b | 31.6 ± 3.0 bc | 118.0 ± 10.1 a | 25.0 ± 2.2 b | 11.3 ± 1.0 bc | 33.7 ± 3.1 a |

| Atomic + herbicide | 18.5 ± 1.5 a | 35.4 ± 3.2 a | 16.4 ± 1.4 ab | 81.5 ± 7.8 bc | 29.0 ± 2.5 bc | 79.1 ± 7.5 b | 22.8 ± 2.0 b | 12.8 ± 1.2 b | 24.4 ± 2.2 b |

| Treatment | Pod Valves | Seeds | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Herbicide | Control | Herbicide | |

| Control | 0.30 ± 0.03 d | 0.63 ± 0.06 a | 0.38 ± 0.03 c | 0.58 ± 0.05 a |

| Siliplant | 0.44 ± 0.04 c | 0.41 ± 0.04 c | 0.24 ± 0.02 d | 0.34 ± 0.03 c |

| BioSi | 0.55 ± 0.05 b | 0.44 ± 0.04 c | 0.42 ± 0.04 b | 0.49 ± 0.04 ab |

| Nano-Si | 0.57 ± 0.05 ab | 0.44 ± 0.04 c | 0. 51 ± 0.05 a | 0.55 ± 0.05 ab |

| Atomic | 0.51 ± 0.05 b | 0.54 ± 0.05 b | 0.41 ± 0.04 bc | 0.47 ± 0.04 b |

| Preparation | Chemical Composition | Dose | Producer |

|---|---|---|---|

| Siliplant | Active Si ≥ 7%, potassium 1%; chelate forms of Fe—300; Mg—100; Cu—70; Zn—80; Mn—150; Mo—60; Co—15; B—90 (mg L−1) | 3 mL L−1 | NEST M (Moscow, Russia) |

| BioSi | Water emulsion of triterpenic acids (100 g L−1); Siberian fir extract; choline stabilized ortho-silicic acid | 1 mL 5 L−1 (0.02 L Ha−1) | Agroimpex (St.Petersburg, Russia) |

| Nano-Si | Nanoparticles of 72 nm size | 10 mg L−1 | Baikov Institute of Metallurgy and Metal Science (Moscow, Russia) |

| Atomic | Syloxan polyalkylenoxide modified by polyether | 4 mL L−1 | Aqualar Corporation (Riga, Latvia) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ushakova, O.; Golubkina, N.; Ushakov, V.; Fedotov, M.; Alpatov, A.; Kravchenko, D.; Datsyuk, K.; Antoshkina, M.; Sindireva, A.; Murariu, O.C.; et al. Effect of Silicon Formulation on Protecting and Boosting Faba Bean Growth Under Herbicide Damage. Stresses 2025, 5, 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/stresses5040068

Ushakova O, Golubkina N, Ushakov V, Fedotov M, Alpatov A, Kravchenko D, Datsyuk K, Antoshkina M, Sindireva A, Murariu OC, et al. Effect of Silicon Formulation on Protecting and Boosting Faba Bean Growth Under Herbicide Damage. Stresses. 2025; 5(4):68. https://doi.org/10.3390/stresses5040068

Chicago/Turabian StyleUshakova, Olga, Nadezhda Golubkina, Vladimir Ushakov, Mikhail Fedotov, Andrey Alpatov, Dmitry Kravchenko, Ksenia Datsyuk, Marina Antoshkina, Anna Sindireva, Otilia Cristina Murariu, and et al. 2025. "Effect of Silicon Formulation on Protecting and Boosting Faba Bean Growth Under Herbicide Damage" Stresses 5, no. 4: 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/stresses5040068

APA StyleUshakova, O., Golubkina, N., Ushakov, V., Fedotov, M., Alpatov, A., Kravchenko, D., Datsyuk, K., Antoshkina, M., Sindireva, A., Murariu, O. C., & Caruso, G. (2025). Effect of Silicon Formulation on Protecting and Boosting Faba Bean Growth Under Herbicide Damage. Stresses, 5(4), 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/stresses5040068