Herbicides Constrain Hyphal Growth, Conidial Germination, and Morphological Transformation in a Dimorphic Fungal Pathogen

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

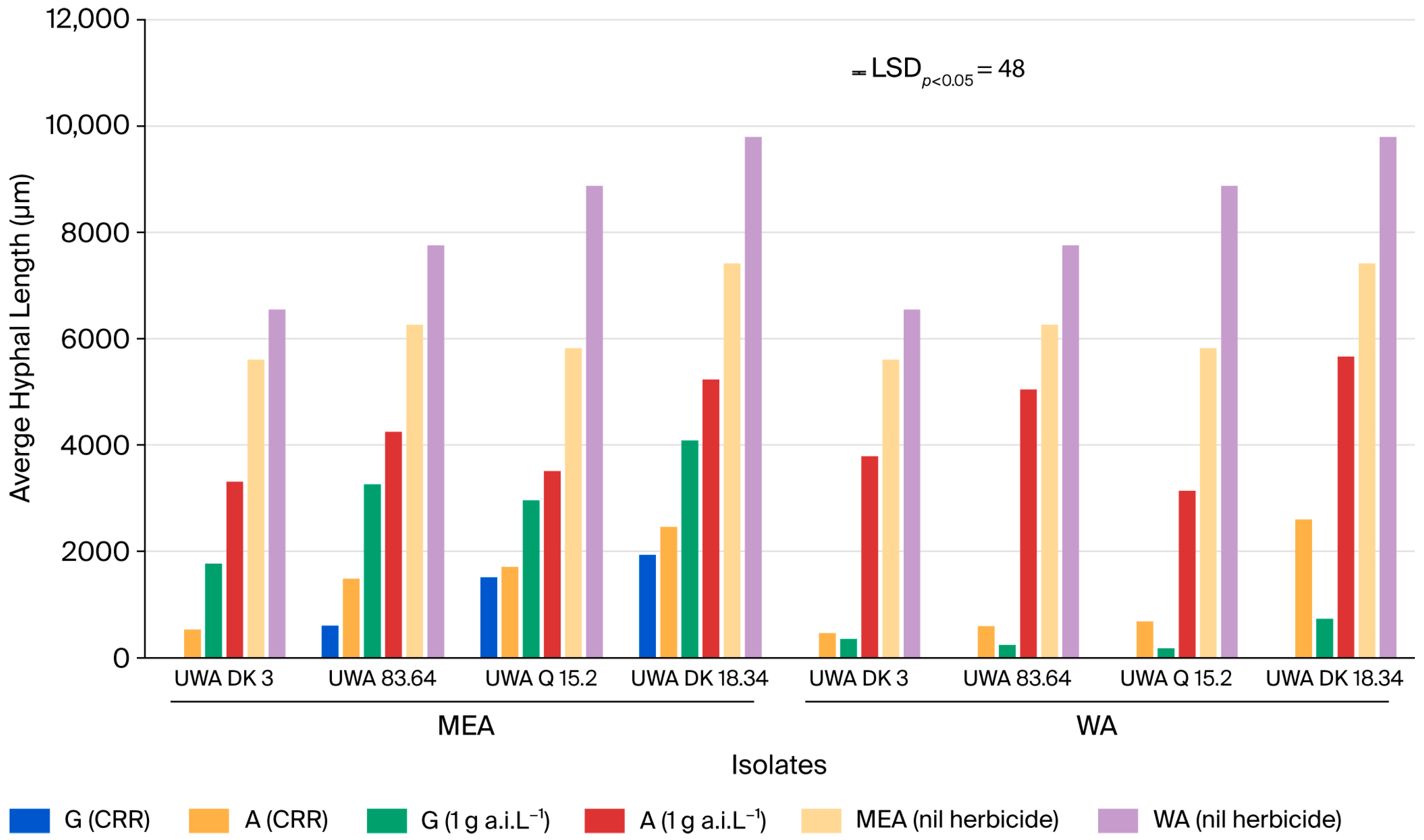

2.1. Hyphal Growth: Overall Significance of Treatments and Their Interactions

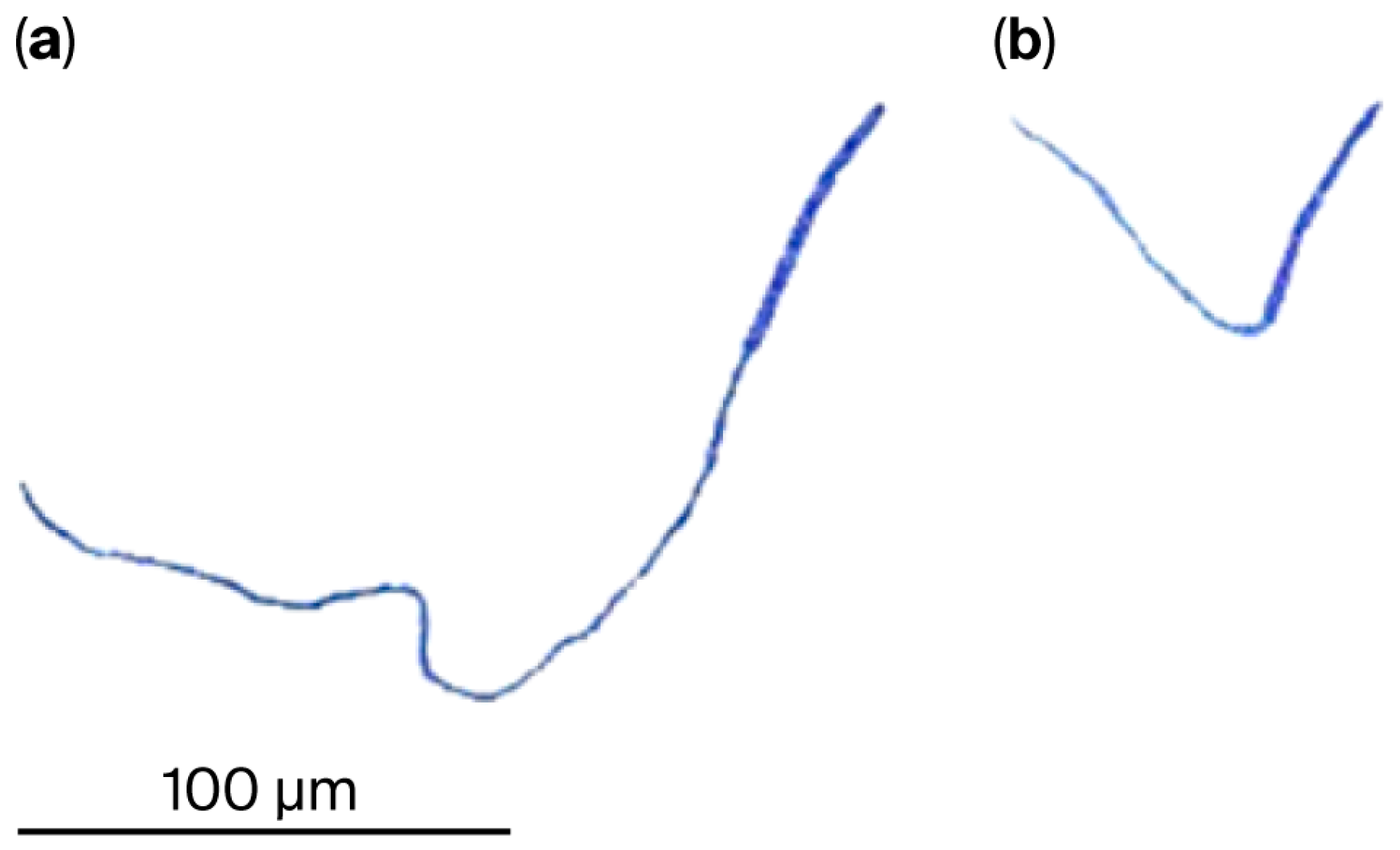

2.2. Conidial Germination: Overall Significance of Treatments and Their Interactions

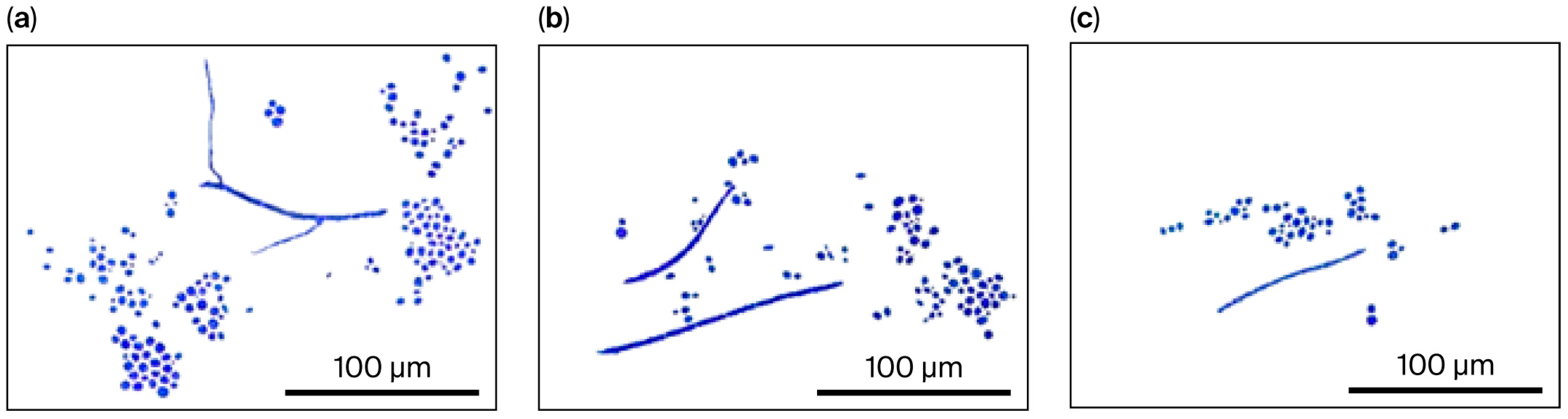

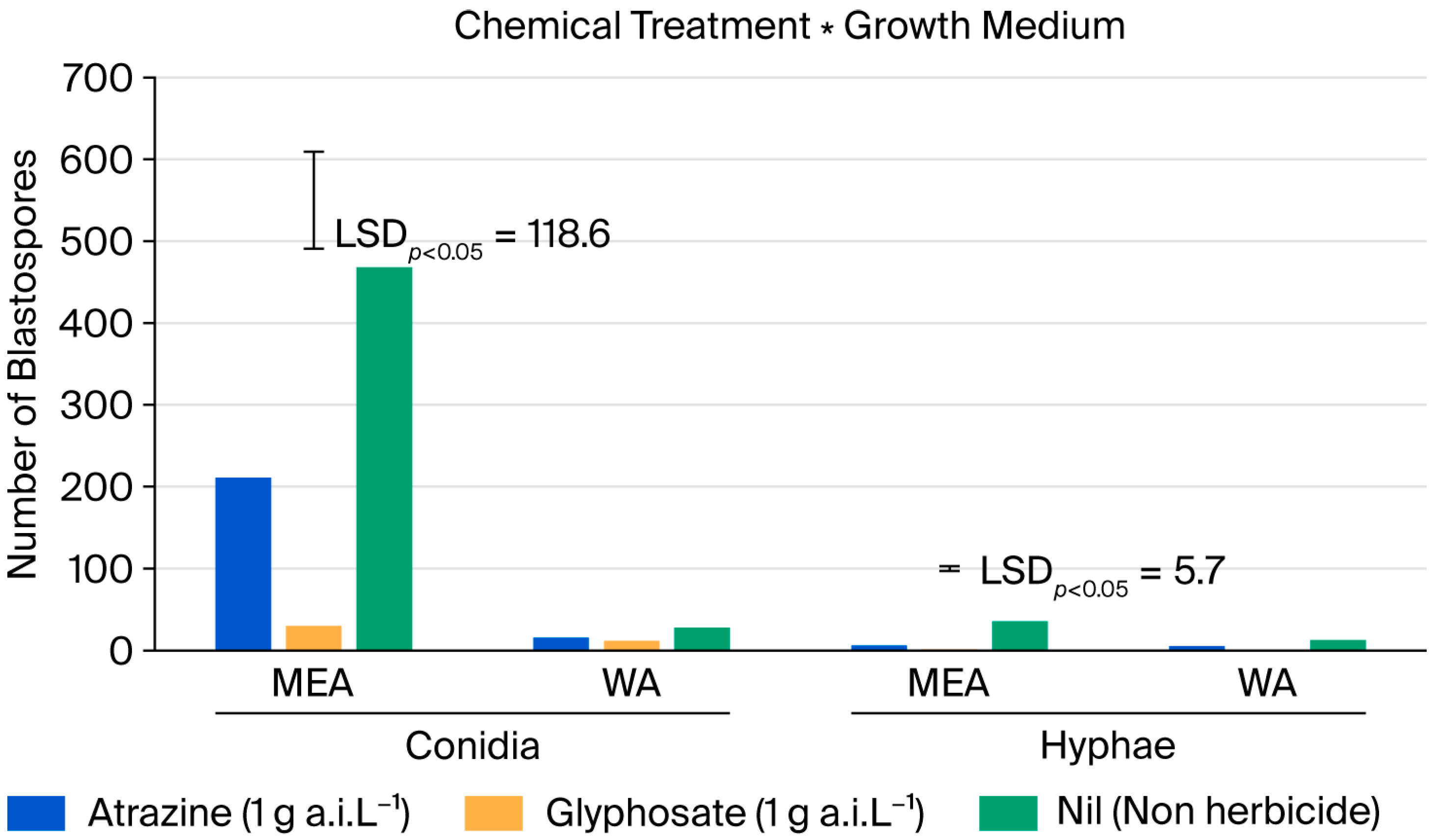

2.3. Morphological Transformation: Overall Significance of Treatments and Their Interactions

2.4. Effect of Applying Atrazine or Glyphosate on Hyphal Growth on Malt Extract Agar (MEA)

2.5. Effect of Application of Atrazine or Glyphosate on Hyphal Growth on Water Agar (WA)

2.6. Effect of Application of Atrazine and Glyphosate on Conidial Germination on Malt Extract Agar (MEA) and Water Agar (WA)

2.7. Effect of Application of Atrazine and Glyphosate on Morphological Transformation of Multi-Celled Hyphae or Conidia to Blastospores on Malt Extract Agar (MEA) and Water Agar (WA)

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Neopseudocercosporella capsellae Isolates

4.2. Herbicides and Their Application

4.3. Treatments

4.4. Experimental Conditions

4.5. Neopseudocercosporella capsellae Mycelial Production

4.6. Neopseudocercosporella capsellae Conidial Production

4.7. Microscopic Determination of Hyphal Growth

4.8. Microscopic Determination of Conidial Germination

4.9. Microscopic Determination of Morphological Transformation from Multi-Celled Hyphae or Conidia into Numerous Single-Celled Blastospores

4.10. Experimental Design and Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MEA | Malt Extract Agar |

| WA | Water Agar |

| MEB | Malt Extract Broth |

| CRR | Commercial Recommended Concentration/Rate |

| RR | Roundup Ready® |

| TT | Triazine-Tolerant |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| EPSPS | 5-Enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase |

References

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Statistics on the Production of Principal Agricultural Commodities Including Cereal and Broadacre Crops, Horticulture and Livestock, 2021–2022 Financial Year. Agricultural Commodities, Australia. 2023. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/industry/agriculture/agricultural-commodities-australia/latest-release (accessed on 17 January 2024).

- Siddiqua, K.A.; Wilson, S.P.; Alquezar, R. Importance of the study of atrazine toxicity to amphibians in the Australian environment. Australas. J. Ecotoxicol. 2010, 16, 103–118. Available online: https://leusch.info/ecotox/aje/archives/vol16p103.pdf (accessed on 29 January 2024).

- Oliver, D.P.; Kookana, R.S.; Miller, R.B.; Correll, R.L. Comparative environmental impact assessment of herbicides used on genetically modified and non-genetically modified herbicide-tolerant canola crops using two risk indicators. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 557, 754–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gianessi, L.P. Economic and herbicide use impacts of glyphosate-resistant crops. Pest Manag. Sci. Former. Pestic. Sci. 2005, 61, 241–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, A.; Kingwell, R. Economic implications of the loss of glyphosate and paraquat on Australian mixed enterprise farms. Agric. Systems. 2021, 193, 103207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Wouw, A.; Idnurm, A.; Davidson, J.; Sprague, S.; Khangura, R.; Ware, A.; Lindbeck, K.D.; Marcroft, S.J. Fungal diseases of canola in Australia: Identification of trends, threats and potential therapies. Australas. Plant Pathol. 2016, 45, 415–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtza, T.; You, M.P.; Barbetti, M.J. Geographic location and year determine virulence, and year determines genetic change, in populations of Neopseudocercosporella capsellae. Plant Pathol. 2019, 68, 1706–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.E.; You, M.P.; Banga, S.S.; Barbetti, M.J. Resistances to downy mildew (Hyaloperonospora brassicae) in diverse Brassicaceae offer new disease management opportunities for oilseed and vegetable crucifer industries. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2019, 153, 915–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-lami, H.F.D.; You, M.P.; Barbetti, M.J. Role of foliage component and host age on severity of Alternaria leaf spot (caused by Alternaria japonica and A. brassicae) in canola (Brassica napus) and mustard (B. juncea) and yield loss in canola. Crop Past. Sci. 2019, 70, 969–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-lami, H.F.; You, M.P.; Mohammed, A.E.; Barbetti, M.J. Virulence variability across the Alternaria spp. population determines incidence and severity of Alternaria leaf spot on rapeseed. Plant Pathol. 2020, 69, 506–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtza, T.; You, M.P.; Barbetti, M.J. Temperature and relative humidity shape white leaf spot (Neopseudocercosporella capsellae) epidemic development in rapeseed (Brassica napus). Plant Pathol. 2021, 70, 1936–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtza, T.; You, M.P.; Barbetti, M.J. Canola growth stage at time of infection determines magnitude of white leaf spot (Neopseudocercosporella capsellae) impact. Plant Dis. 2021, 105, 1515–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakdaman Sardrood, B.; Mohammadi Goltapeh, E. Weeds, herbicides and plant disease management. In Sustainable Agriculture Reviews; Lichtfouse, E., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 31, pp. 41–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtza, T.; You, M.P.; Barbetti, M.J. Application timing of herbicides, glyphosate and atrazine, sway respective epidemics of foliar pathogens in herbicide--tolerant rapeseed. Plant Pathol. 2022, 71, 507–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, Y.; You, M.P.; Yan, G.; Barbetti, M.J. Atrazine application shapes white leaf spot (Neopseudocercosporella capsellae) development on triazine-resistant canola. Plant Health Prog. 2024, 26, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, Y.; You, M.P.; Yan, G.; Barbetti, M.J. Glyphosate application affects white leaf spot (Neopseudocercosporella capsellae) development on glyphosate-tolerant canola. Plant Pathol. 2024, 74, 786–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunasinghe, N.; Barbetti, M.J.; You, M.P.; Dehigaspitiya, P.; Neate, S. Dimorphism in Neopseudocercosporella capsellae, an emerging pathogen causing white leaf spot disease of Brassicas. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 678231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cupul, W.C.; Abarca, G.H.; Vázquez, R.R.; Salmones, D.; Hernández, R.G.; Gutiérrez, E.A. Response of ligninolytic macrofungi to the herbicide atrazine: Dose-response bioassays. Rev. Argent. Microbiol. 2014, 46, 348–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isakeit, T.; Lockwood, J.L. Lethal effect of triazine and other triazine herbicides on ungerminated conidia of Cochliobolus sativus in soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1989, 21, 809–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, J.; Campbell, C.L. Effect of herbicides on plant diseases. Ann. Rev. Phytopathol. 1977, 15, 361–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanyal, D.; Shrestha, A. Direct effect of herbicides on plant pathogens and disease development in various cropping systems. Weed Sci. 2008, 56, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, V.; Noonikara-Poyil, A.; Joshi, S.D.; Patil, S.A.; Patil, S.A.; Lewis, A.M.; Bugarin, A. Synthesis, molecular docking studies, and in vitro evaluation of 1, 3, 5-triazine derivatives as promising antimicrobial agents. J. Mol. Struct. 2020, 1220, 128687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, S.; Kumar, A.; Achary, V.M.M.; Ganesan, P.; Rathi, N.; Singh, A.; Sahu, K.P.; Lal, S.K.; Das, T.K.; Reddy, M.K. Antifungal activity of glyphosate against fungal blast disease on glyphosate-tolerant OsmEPSPS transgenic rice. Plant Sci. 2021, 311, 111009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larson, R.L.; Hill, A.L.; Fenwick, A.; Kniss, A.R.; Hanson, L.E.; Miller, S.D. Influence of glyphosate on Rhizoctonia and Fusarium root rot in sugar beet. Pest Manag. Sci. Former. Pestic. Sci. 2006, 62, 1182–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyss, G.S.; Müller-Schärer, H. Effects of selected herbicides on the germination and infection process of Puccinia lagenophorae, a biocontrol pathogen of Senecio vulgaris. Biol. Control. 2001, 20, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, P.C.C.; Baley, G.J.; Clinton, W.P.; Bunkers, G.J.; Alibhai, M.F.; Paulitz, T.C.; Kidwell, K.K. Glyphosate inhibits rust diseases in glyphosate-resistant wheat and soybean. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 17290–17295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richards, T.A.; Dacks, J.B.; Campbell, S.A.; Blanchard, J.L.; Foster, P.G.; McLeod, R.; Roberts, C.W. Evolutionary origins of the eukaryotic shikimate pathway: Gene fusions, horizontal gene transfer, and endosymbiotic replacements. Eukaryot. Cell 2006, 5, 1517–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Light, S.H.; Krishna, S.N.; Minasov, G.; Anderson, W.F. An unusual cation-binding site and distinct domain–domain interactions distinguish class II enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthases. Biochemistry 2016, 55, 1239–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardle, D.A.; Parkinson, D. Influence of the herbicide glyphosate on soil microbial community structure. Plant Soil. 1990, 122, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkinson, D.S.; Powlson, D.S. The effects of biocidal treatments on metabolism in soil—V: A method for measuring soil biomass. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1976, 8, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zobiole, L.H.S.; Kremer, R.J.; Oliveira, R.S., Jr.; Constantin, J. Glyphosate affects micro-organisms in rhizospheres of glyphosate-resistant soybeans. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2011, 110, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, P.C.; Chiu, T.; Sammons, R.D. Glyphosate efficacy is contributed by its tissue concentration and sensitivity in velvetleaf (Abutilon theophrasti). Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2003, 77, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremer, R.; Means, N.; Kim, S. Glyphosate affects soybean root exudation and rhizosphere micro-organisms. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2005, 85, 1165–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromilow, R.H.; Chamberlain, K.; Tench, A.J.; Williams, R.H. Phloem translocation of strong acids—Glyphosate, substituted phosphonic and sulfonic acids—In Ricinus communis L. Pestic. Sci. 1993, 37, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, M.P.; Smedbol, E.; Chalifour, A.; Hénault-Ethier, L.; Labrecque, M.; Lepage, L.; Juneau, P. Alteration of plant physiology by glyphosate and its by-product aminomethylphosphonic acid: An overview. J. Exp. Bot. 2014, 65, 4691–4703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunasinghe, N.; You, M.P.; Clode, P.L.; Barbetti, M.J. Mechanisms of resistance in Brassica carinata, B. napus and B. juncea to Pseudocercosporella capsellae. Plant Pathol. 2016, 65, 888–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, S.O.; Sepúlveda, L.A.; Xu, H.; Golding, I. Measuring mRNA copy number in individual Escherichia coli cells using single-molecule fluorescent in situ hybridization. Nat. Protoc. 2013, 8, 1100–1113, Correction in Nat. Protoc. 2015, 10, 1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ai, Y.; You, M.P.; Yan, G.; Barbetti, M.J. Herbicides Constrain Hyphal Growth, Conidial Germination, and Morphological Transformation in a Dimorphic Fungal Pathogen. Stresses 2025, 5, 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/stresses5040067

Ai Y, You MP, Yan G, Barbetti MJ. Herbicides Constrain Hyphal Growth, Conidial Germination, and Morphological Transformation in a Dimorphic Fungal Pathogen. Stresses. 2025; 5(4):67. https://doi.org/10.3390/stresses5040067

Chicago/Turabian StyleAi, Yan, Ming Pei You, Guijun Yan, and Martin J. Barbetti. 2025. "Herbicides Constrain Hyphal Growth, Conidial Germination, and Morphological Transformation in a Dimorphic Fungal Pathogen" Stresses 5, no. 4: 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/stresses5040067

APA StyleAi, Y., You, M. P., Yan, G., & Barbetti, M. J. (2025). Herbicides Constrain Hyphal Growth, Conidial Germination, and Morphological Transformation in a Dimorphic Fungal Pathogen. Stresses, 5(4), 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/stresses5040067