A Behavioral Theory of Market Retrenchment: Role of Changes in Market Shares and Market Attractiveness

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theory and Hypotheses

2.1. The Behavioral Theory of the Firm

2.2. Market Attractiveness as a Cognitive Frame: An Attention-Based View

2.3. Research Context: The Japanese Life Insurance Industry

2.4. Market Attractiveness and Market Retrenchment

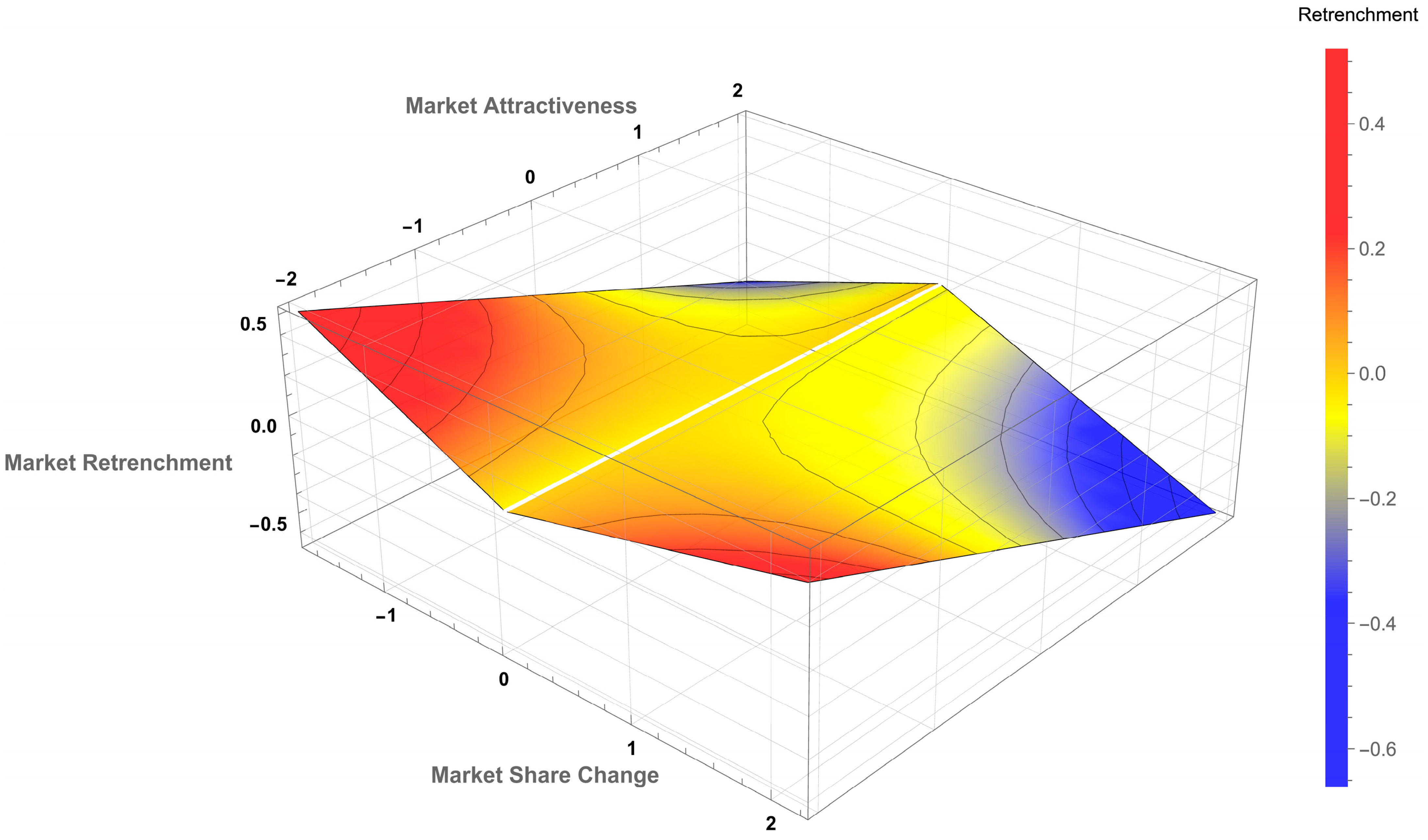

2.5. Market Share Changes in Markets with Average Attractiveness

2.6. Market Share Changes in Markets with High and Low Attractiveness

3. Methods

3.1. Data and Sample

3.2. Variables

3.3. Model

4. Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions and Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ESG | Environmental, Social, and Governance |

| GEE | Generalized estimating equation |

| HHI | Herfindahl–Hirschman Index |

| OLS | Ordinary least squares |

| ROA | Return on assets |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| SWOT | Strength, weakness, opportunity, threat |

| VIF | Variance inflation factor |

References

- Arrfelt, M., Wiseman, R. M., & Hult, G. T. M. (2013). Looking backward instead of forward: Aspiration-driven influences on the efficiency of the capital allocation process. Academy of Management Journal, 56(4), 1081–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audia, P. G., & Brion, S. (2007). Reluctant to change: Self-enhancing responses to diverging performance measures. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 102(2), 255–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audia, P. G., & Greve, H. R. (2021). Organizational learning from performance feedback: A behavioral perspective on multiple goals: A multiple goals perspective. Elements in Organization Theory. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballinger, G. A. (2004). Using generalized estimating equations for longitudinal data analysis. Organizational Research Methods, 7(2), 127–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto, I. (2012). A behavioral theory of market expansion based on the opportunity prospects rule. Organization Science, 23(4), 1008–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, J. A. C., Rowley, T. J., Shipilov, A. V., & Chuang, Y.-T. (2005). Dancing with strangers: Aspiration performance and the search for underwriting syndicate partners. Administrative Science Quarterly, 50(4), 536–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettis, R. A., & Mahajan, V. (1985). Risk return performance of diversified firms. Management Science, 31(7), 785–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, A. C., & Miller, D. L. (2015). A practitioner’s guide to cluster-robust inference. Journal of Human Resources, 50(2), 317–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, A. C., & Trivedi, P. K. (2013). Regression analysis of count data. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.-R. (2008). Determinants of firms’ backward- and forward-looking R&D search behavior. Organization Science, 19(4), 609–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyert, R. M., & March, J. G. (1963). A behavioral theory of the firm. Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Dowell, G., & Killaly, B. (2009). Effect of resource variation and firm experience on market entry decisions: Evidence from U.S. telecommunication firms’ international expansion decisions. Organization Science, 20(1), 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggers, J., & Suh, J.-H. (2019). Experience and behavior: How negative feedback in new versus experienced domains affects firm action and subsequent performance. Academy of Management Journal, 62(2), 309–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greve, H. R. (1998). Performance, aspirations, and risky organizational change. Administrative Science Quarterly, 43(1), 58–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greve, H. R. (2003a). A behavioral theory of R&D expenditures and innovations: Evidence from shipbuilding. Academy of Management Journal, 46(6), 685–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greve, H. R. (2003b). Organizational learning from performance feedback: A behavioral perspective on innovation and change. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Greve, H. R. (2008). A behavioral theory of firm growth: Sequential attention to size and performance goals. Academy of Management Journal, 51(3), 476–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S. (2023). The effect of performance feedback on strategic alliance formation and R&D intensity. European Management Journal, 41(5), 709–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardin, J. W., & Hilbe, J. M. (2002). Generalized estimating equations. Chapman and Hall/CRC. [Google Scholar]

- Harrigan, K. R. (1980). Strategy formulation in declining industries. Academy of Management Review, 5(4), 599–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilbe, J. M. (2011). Negative binomial regression. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard, A. E., Ahern, J., Fleischer, N. L., Laan, M. V. D., Lippman, S. A., Jewell, N., Bruckner, T., & Satariano, W. A. (2010). To GEE or not to GEE: Comparing population average and mixed models for estimating the associations between neighborhood risk factors and health. Epidemiology, 21(4), 467–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, P. J. (1967). The behavior of maximum likelihood estimates under nonstandard conditions. In J. Neyman, & L. LeCam (Eds.), Proceedings of the fifth berkeley symposium on mathematical statistics and probability (pp. 221–233). University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Iyer, D. N., & Miller, K. D. (2008). Performance feedback, slack, and the timing of acquisitions. Academy of Management Journal, 51(4), 808–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaccard, J., & Turrisi, R. (2003). Interaction effects in multiple regression. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, A. H., & Audia, P. G. (2012). Self-enhancement and learning from performance feedback. Academy of Management Review, 37(2), 211–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, J., & Gaba, V. (2015). The fog of feedback: Ambiguity and firm responses to multiple aspiration levels. Strategic Management Journal, 36(13), 1960–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, J., Laureiro-Martinez, D., Nigam, A., Ocasio, W., & Rerup, C. (2024). Research frontiers on the attention-based view of the firm. Strategic Organization, 22(1), 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S. (2008). Framing contests: Strategy making under uncertainty. Organization Science, 19(5), 729–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, P. (2008). A guide to econometrics. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.-Y., Finkelstein, S., & Haleblian, J. (2015). All aspirations are not created equal: The differential effects of historical and social aspirations on acquisition behavior. Academy of Management Journal, 58(5), 1361–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-Y., & Miner, A. S. (2007). Vicarious learning from the failures and near-failures of others: Evidence from the U.S. commercial banking industry. Academy of Management Journal, 50(3), 687–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- König, A., Graf-Vlachy, L., & Schöberl, M. (2021). Opportunity/Threat perception and inertia in response to discontinuous change: Replicating and extending gilbert (2005). Journal of Management, 47(3), 771–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, K. Y., & Zeger, S. L. (1986). Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear-models. Biometrika, 73(1), 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, L. C., & Cormier, D. R. (2001). Spline regression models (Vol. 137). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Menon, T., & Pfeffer, J. (2003). Valuing internal vs. external knowledge: Explaining the preference for outsiders. Management Science, 49(4), 497–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocasio, W. (1997). Towards an attention-based view of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 18(S1), 187–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickton, D. W., & Wright, S. (1998). What’s swot in strategic analysis? Strategic Change, 7(2), 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M. E. (1980). Competitive strategy: Techniques for analyzing industries and competition. Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rhee, M., & Haunschild, P. R. (2006). The liability of good reputation: A study of product recalls in the U.S. automobile industry. Organization Science, 17(1), 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seow, R. Y. C. (2025). The dynamics of performance feedback and ESG disclosure: A behavioral theory of the firm perspective. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 32(2), 2598–2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, K. (2007). Prospect theory, behavioral theory, and the threat-rigidity thesis: Combinative effects on organizational decisions to divest formerly acquired units. Academy of Management Journal, 50(6), 1495–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinkle, G. A. (2011). Organizational aspirations, reference points, and goals. Journal of Management, 38(1), 415–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staw, B. M. (1976). Knee-deep in the big muddy: A study of escalating commitment to a chosen course of action. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 16(1), 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staw, B. M. (1981). The escalation of commitment to a course of action. Academy of Management Review, 6(4), 577–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thywissen, C. (2015). Divestiture decisions: Conceptualization through a strategic decision-making lens. Management Review Quarterly, 65(2), 69–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, E., & Mitchell, W. (2015). Adding by subtracting: The relationship between performance feedback and resource reconfiguration through divestitures. Organization Science, 26(4), 1101–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuori, T. O., & Huy, Q. N. (2016). Distributed attention and shared emotions in the innovation process: How nokia lost the smartphone battle. Administrative Science Quarterly, 61(1), 9–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weihrich, H. (1982). The TOWS matrix—A tool for situational analysis. Long Range Planning, 15(2), 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, H. (1980). A heteroskedasticity-consistent covariance matrix estimator and a direct test for heteroskedasticity. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society, 48, 817–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wooldridge, J. M. (2010). Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M., Shui, X., Smart, P., Wang, X., & Chen, J. (2023). Environmental performance feedback and timing of reshoring: Perspectives from the behavioural theory of the firm. British Journal of Management, 34(3), 1238–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Loss in Market Share | Gain in Market Share | |

|---|---|---|

| High Market Attractiveness | Decreases (H4) | Decreases (H5) |

| Average Market Attractiveness | No change (H2) | Decreases (H3) |

| Low Market Attractiveness | Increases (H4) | Increases (H5) |

| Variable | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Market retrenchment | 0.763 | 2.065 | ||||||||||||

| 2. Market attractiveness | 5.242 | 1.227 | 0.083 | |||||||||||

| 3. Market share loss | −0.366 | 0.649 | −0.073 | 0.026 | ||||||||||

| 4. Market share gain | 0.253 | 0.958 | −0.028 | 0.083 | 0.149 | |||||||||

| 5. Market households a | 0.008 | 1.004 | 0.412 | 0.399 | 0.029 | 0.002 | ||||||||

| 6. Market competition density a | −0.490 | 0.628 | −0.219 | −0.770 | −0.024 | −0.046 | −0.727 | |||||||

| 7. Own local density | 19.11 | 23.045 | 0.617 | 0.334 | −0.157 | 0.070 | 0.722 | −0.564 | ||||||

| 8. Prefecture size | 0.008 | 0.011 | 0.069 | −0.001 | 0.003 | −0.019 | 0.115 | −0.017 | 0.134 | |||||

| 9. Return on assets | 0.003 | 0.008 | 0.017 | 0.115 | 0.042 | 0.038 | 0.002 | −0.068 | 0.100 | 0.001 | ||||

| 10. Firm slack | −0.053 | 0.128 | 0.084 | 0.029 | −0.135 | 0.098 | 0.012 | −0.021 | 0.176 | 0.005 | −0.018 | |||

| 11. Firm size b | 14.02 | 0.979 | 0.153 | 0.261 | −0.280 | 0.189 | −0.006 | −0.148 | 0.412 | 0.001 | 0.228 | 0.464 | ||

| 12. Geographic diversification | 0.957 | 0.023 | 0.011 | 0.016 | −0.063 | −0.005 | −0.116 | 0.021 | 0.086 | 0.003 | 0.023 | −0.132 | 0.124 | |

| 13. Industry clock | 4.823 | 3.444 | −0.109 | 0.443 | 0.165 | 0.056 | −0.034 | −0.285 | −0.019 | −0.001 | 0.133 | −0.089 | 0.099 | −0.030 |

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Market households | 0.074 (0.069) | 0.097 (0.060) | 0.071 (0.066) | 0.094 (0.058) | 0.090 (0.055) |

| Market competition density | −0.060 (0.065) | 0.087 (0.070) | −0.054 (0.064) | 0.093 (0.074) | 0.120 (0.077) |

| Own local density | 0.026 ** (0.002) | 0.026 ** (0.002) | 0.027 ** (0.002) | 0.027 ** (0.002) | 0.027 ** (0.002) |

| Prefecture size | 7.409 ** (1.950) | 7.310 ** (1.945) | 7.100 ** (1.962) | 7.001 ** (1.955) | 6.917 ** (1.952) |

| Return on assets | −9.688 † (5.829) | −9.788 † (5.862) | −10.258 † (5.708) | −10.337 † (5.742) | −10.484 † (5.769) |

| Firm slack | −0.326 (0.950) | −0.283 (0.940) | −0.314 (0.973) | −0.271 (0.929) | −0.276 (0.932) |

| Firm size | 0.134 (0.157) | 0.116 (0.155) | 0.167 (0.155) | 0.148 (0.154) | 0.140 (0.152) |

| Geographic diversification | −3.235 * (1.499) | −3.122 * (1.483) | −3.376 * (1.475) | −3.264 * (1.462) | −3.360 * (1.445) |

| Industry clock | −0.073 * (0.033) | −0.078 * (0.033) | −0.071 * (0.034) | −0.075 * (0.033) | −0.076 * (0.033) |

| Market attractiveness | 0.124 * (0.054) | 0.123 * (0.056) | 0.216 ** (0.069) | ||

| Market share loss | 0.064 (0.045) | 0.059 (0.045) | −0.038 (0.066) | ||

| Market share gain | −0.204 ** (0.056) | −0.202 ** (0.057) | −0.073 (0.050) | ||

| Market share loss × Market attractiveness | 0.135 ** (0.044) | ||||

| Market share gain × Market attractiveness | −0.115 ** (0.029) | ||||

| Wald chi-squared | 3337.23 | 3687.22 | 5318.94 | 5987.89 | 92,977.05 |

| df (for Wald chi-squared) | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 14 |

| p-value | p < 0.01 | p < 0.01 | p < 0.01 | p < 0.01 | p < 0.01 |

| Number of observations | 4223 | 4223 | 4223 | 4223 | 4223 |

| Number of groups | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sasaki, H. A Behavioral Theory of Market Retrenchment: Role of Changes in Market Shares and Market Attractiveness. Businesses 2025, 5, 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/businesses5030040

Sasaki H. A Behavioral Theory of Market Retrenchment: Role of Changes in Market Shares and Market Attractiveness. Businesses. 2025; 5(3):40. https://doi.org/10.3390/businesses5030040

Chicago/Turabian StyleSasaki, Hiroyuki. 2025. "A Behavioral Theory of Market Retrenchment: Role of Changes in Market Shares and Market Attractiveness" Businesses 5, no. 3: 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/businesses5030040

APA StyleSasaki, H. (2025). A Behavioral Theory of Market Retrenchment: Role of Changes in Market Shares and Market Attractiveness. Businesses, 5(3), 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/businesses5030040