1. Introduction

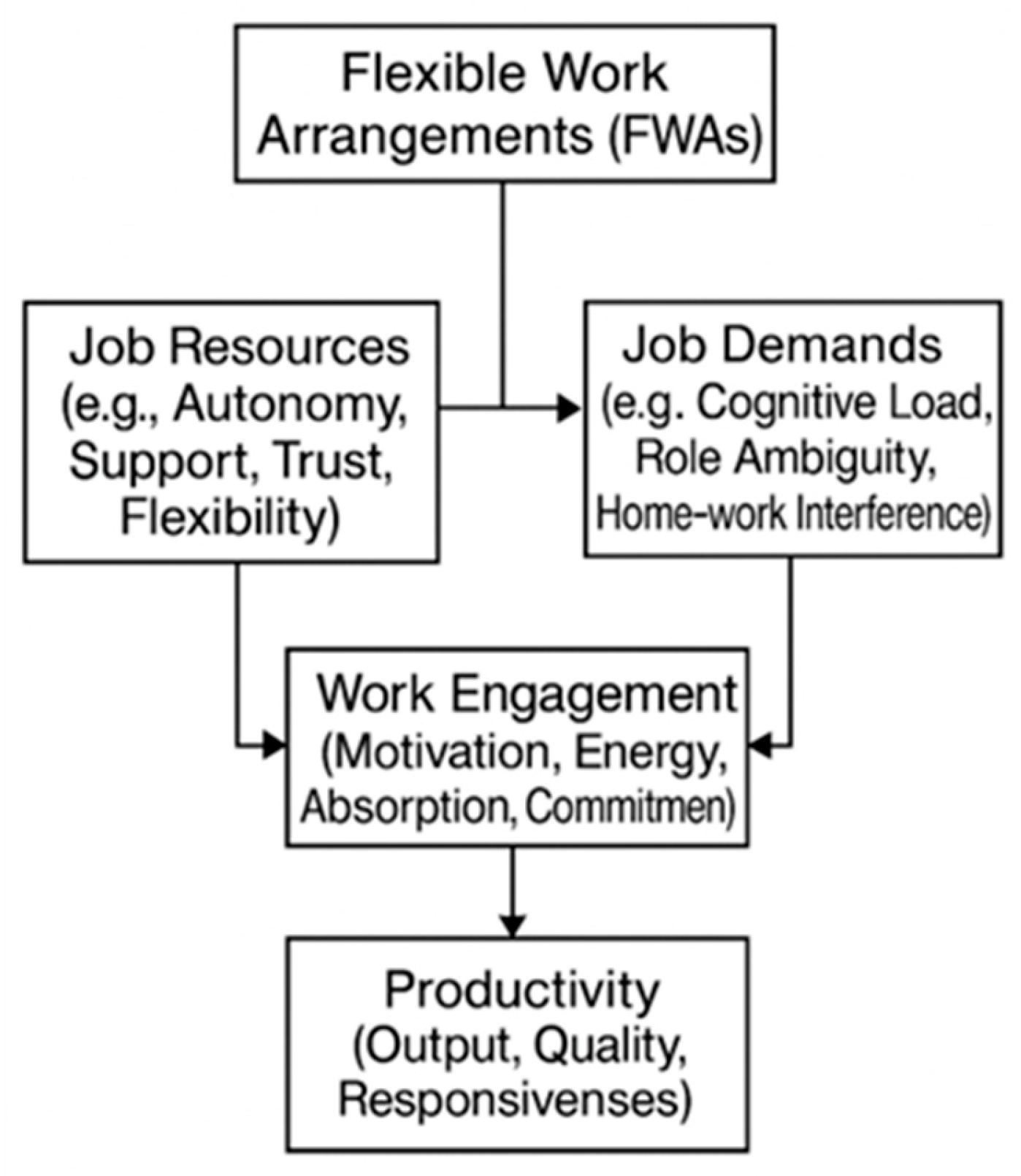

From an organisational standpoint, flexible work arrangements are increasingly significant for productivity and employee wellbeing. This study contributes by applying the Job Demands–Resources (JD-R) model to explore how employee experiences under FWAs translate into perceived productivity, highlighting both practical and theoretical implications.

From the perspective of the employee, FWAs are shown to influence job satisfaction, engagement, and mental wellbeing. Our research builds on this by empirically testing how specific positive and negative employee experiences interact with management strategies to shape productivity outcomes.

Research suggests FWAs have a positive correlation with employee engagement and employee productivity (

Bal & De Lange, 2015;

Hakanen et al., 2018). Additionally, FWAs have been identified as a means to assist in maintaining work–life balance, employee wellbeing and productivity. This suggests an opportunity to further explore FWAs on employee experiences, and the impact this has on employee productivity.

Employee productivity can be considered a significant priority for both organisations and employees (

Galanti et al., 2021). From an organisational perspective, FWAs implemented with effective management strategies are suggested to positively impact employee productivity. From an employee perspective, FWAs implemented with effective management strategies are suggested to improve employee experience, positively impact productivity, reduce job stress and promote desirable mental health.

JD-R model will serve as a theoretical framework used to guide this study. The JD-R model provides insight to better understand the relationship between employees and management, influenced by job demands and job resources (

Bakker & Demerouti, 2007).

The research question of this study is: What is the relationship between employee experiences (EEs) and perceived productivity (PP) and what effect do FWAs have on this relationship?

The key findings show that there was a statistically significant relationship between employees’ experience, expressed as opportunities, and perceived productivity, as well as between employees’ experience, expressed as challenges, and perceived productivity.

2. Literature Review

Alternative working arrangements have increased in number and variety and are becoming increasingly popular in research (

Boeri et al., 2020;

Burchardt & Maisch, 2019;

Hunter, 2019). These trends are being driven not only by technological advances, but also by cultural shifts as employees demand more flexibility. Alternative working arrangements, defined by both working conditions and employee relationships with their employer, are heterogeneous in nature and have seen many changes throughout history. An alternative work arrangement in the literature is defined as a “nontraditional job”-an alternative work arrangement could involve an employee hired by a temporary employment agency, an independent contractor working for various clients, an independent contractor for a single client, an employee working from home, or an employee with a flexible or irregular schedule. Part-time and full-time employment is also considered an alternative work arrangement, as this is an important job characteristic for an employee seeking flexibility in their employment.

Organisations have implemented flexible and alternative work arrangements as a means of enhancing employee engagement and productivity, as well as attracting and retaining talented employees (

Huws et al., 2017;

Spreitzer et al., 2017;

Masselot & Hayes, 2020). The implementation of flexibility within an organisation to enhance agility may pose considerable challenges for its employees. However, providing flexibility to meet the demands of employees can result in a more favourable experience for the employee (

Spreitzer et al., 2017).

Employee experience is a people-first management philosophy that defines what works in organisations, by investigating workplace factors that have the greatest impact on employees (

Plaskoff, 2017). It is a combination of an organisation’s cultural, physical, and technological environments that enables, empowers, and improves employees’ overall evaluation of their workplace’s positiveness (

Luthans & Youssef-Morgan, 2017). Employee experience encompasses everything that employees encounter, big or small, good or bad, during their time employed by their organisations, from the time they apply for a job to the time they wish to leave as an alumna (

Farndale & Kelliher, 2013;

Panneerselvam & Balaraman, 2022). Employee engagement is determined by positive employee experience, which is likely to create a ‘positivity spiral’ of culture, experience, and engagement in the long run (

Maylett & Wride, 2017). Organisations are increasingly investing in employee experience as in is recognised that employee experience and engagement are linked, but employee experience is the means to achieve the latter objective in a long-term way (

Panneerselvam & Balaraman, 2022). Measuring employee experience begins with a fundamental understanding of what employees expect and develops to identifying factors of support, empowerment, and enablement to be successful in jobs and roles. Organisations continue to look for insights into how their organisations can ensure competitiveness through optimal organisational management and improved employee experiences – of which employee engagement is seen as a key component (

Turner & Turner, 2020).

Work factors can have a considerable impact on employees’ overall health and wellbeing, which in turn impacts on job performance and other organisational outcomes (

Bakker et al., 2007;

Van den Broeck et al., 2013).

de Leede and Heuver (

2016) noted employees’ remote work productivity can also be influenced by leadership and organisational support. While job demands (for example, workload, time constraints, and emotional interactions) are not necessarily negative, they require employees’ efforts, and continued exposure to job demands depletes employees’ energy reserves and can evolve into job stressors (

Bakker et al., 2007;

Demerouti et al., 2001;

Schaufeli & Bakker, 2004) Resources like peer support, leadership, resilience, and social support can help employees cope with the negative effects and meet the demands of their jobs. Resources are a concept that includes situational aspects of the workplace and individual traits that facilitate the achievement of work objectives, lower the demands of the job and the costs associated with them, and have a direct impact on both individual and organisational wellbeing measures (

Bakker et al., 2007;

Brauchli et al., 2015;

Demerouti et al., 2001).

The JD-R model offers a lens to understand the relationship between managers and employees, influenced by the job demands and job resources of an organisation. The JD-R model has also been used to predict a variety of employee work-related attitudes, including work engagement, work enjoyment (

Bakker et al., 2010), job satisfaction (

Martinussen et al., 2007), and acceptance of organisational change (

Hetty van Emmerik et al., 2009). The model also has the ability to predict employee behaviour and significant organisational outcomes, such as job performance, presenteeism (

Demerouti et al., 2009), absenteeism (

Schaufeli et al., 2009), productivity, organisational commitment, employee turnover, and turnover intentions (

Bakker et al., 2003;

Van den Broeck et al., 2013).

Job demands are those aspects of a job that necessitate a significant amount of physical or mental effort and are hence associated with physiological and/or psychological expenses (e.g., high work pressure, an unpleasant physical environment, and emotionally challenging customer engagement) (

Demerouti et al., 2001). Job resources are physical, social, and organisational job characteristics that help employees achieve their goals, reduce job demands and their associated costs, or promote personal growth and development. Job resources include a variety of factors (such as management support, supervisor feedback, skill development, and autonomy) that motivate employees and mitigate the effects of increased job demands (

Demerouti et al., 2001).

Crawford et al. (

2010) enlarge this definition through the differentiation between hindering and challenging job demands. Challenging job demands may promote employee’s personal growth and future gains and tend to be perceived as opportunities to learn, whereas hindering job demands may thwart employee’s personal growth and tend to be perceived as constraints or barriers (

Crawford et al., 2010).

Figure 1 presents the adapted JD-R framework guiding this study, illustrating the hypothesised relationships between flexible work arrangements, job resources, job demands, work engagement, and productivity.

Flexible working arrangements enable employees to work at different times and different locations while performing the same activities and having the same responsibilities and requirements. Despite the remote nature of work, it remains important for managers to develop the skills necessary to effectively supervise, maintain communication with, and optimise the performance of their team (

Lautsch et al., 2009). The challenge in managing employees working flexibly lies in the reduced possibilities of monitoring employee behaviour (

Allen et al., 2015;

Bloom et al., 2015). Because flexible working is mostly implemented in an existing setting, with existing operations, procedures, activities and policies, in general, similar controls will be present in flexible working and non-flexible working situations. The essence of flexible working arrangements is that they provide flexibility to the employees without impacting the organisation as a whole (

Groen et al., 2018;

Green et al., 2020). As a result, when managers allow employees to work flexibly, they can often use the existing controls and apply these controls differently to employees that work flexibly and those employees who do not, by placing different levels of emphasis on them.

Lautsch et al. (

2009) found that around 25 percent of managers with experience in supervising employees working flexibly reported that they use written performance standards and performance feedback differently from those for non-flexible working employees. Accordingly,

Richardson and McKenna (

2014) found that employees working flexibly feel more pressure to meet performance objectives than those who do not work flexibly.

Flexible working arrangements allow employees to work when they are most productive, and it can be useful for avoiding coworker distractions, especially in open plan offices (

Kim & De Dear, 2013;

Tavares, 2017). Employees can take a break from their offices and focus on organising an individualised approach to their work–life balance, which can encourage a healthier lifestyle, which benefits both physical and mental health. Previous research has also shown that flexible working arrangements can improve employee wellbeing by giving employees more flexibility, increasing employee productivity, and allowing employees to better balance their home and work lives (

Mann & Holdsworth, 2003;

Bilotta et al., 2021). While there are advantages to flexible working arrangements, there are also significant disadvantages. For others, blurred work–life boundaries make it difficult to psychologically separate from work, increasing stress and worry (

Evanoff et al., 2020;

Majumdar et al., 2020;

Mann & Holdsworth, 2003;

Tavares, 2017). Balancing work schedules around other family members is a typical area of concern in work–life boundaries, where for some parents, work time becomes ‘porous’ since they may need to take care of domestic tasks and run errands in between work meetings (

Messenger et al., 2017).

The challenge for organisations lies in developing strategies to effectively manage employees working from home and for both employees and organisations to reap the potential benefits while also ensuring employee wellbeing is protected and productivity is maintained.

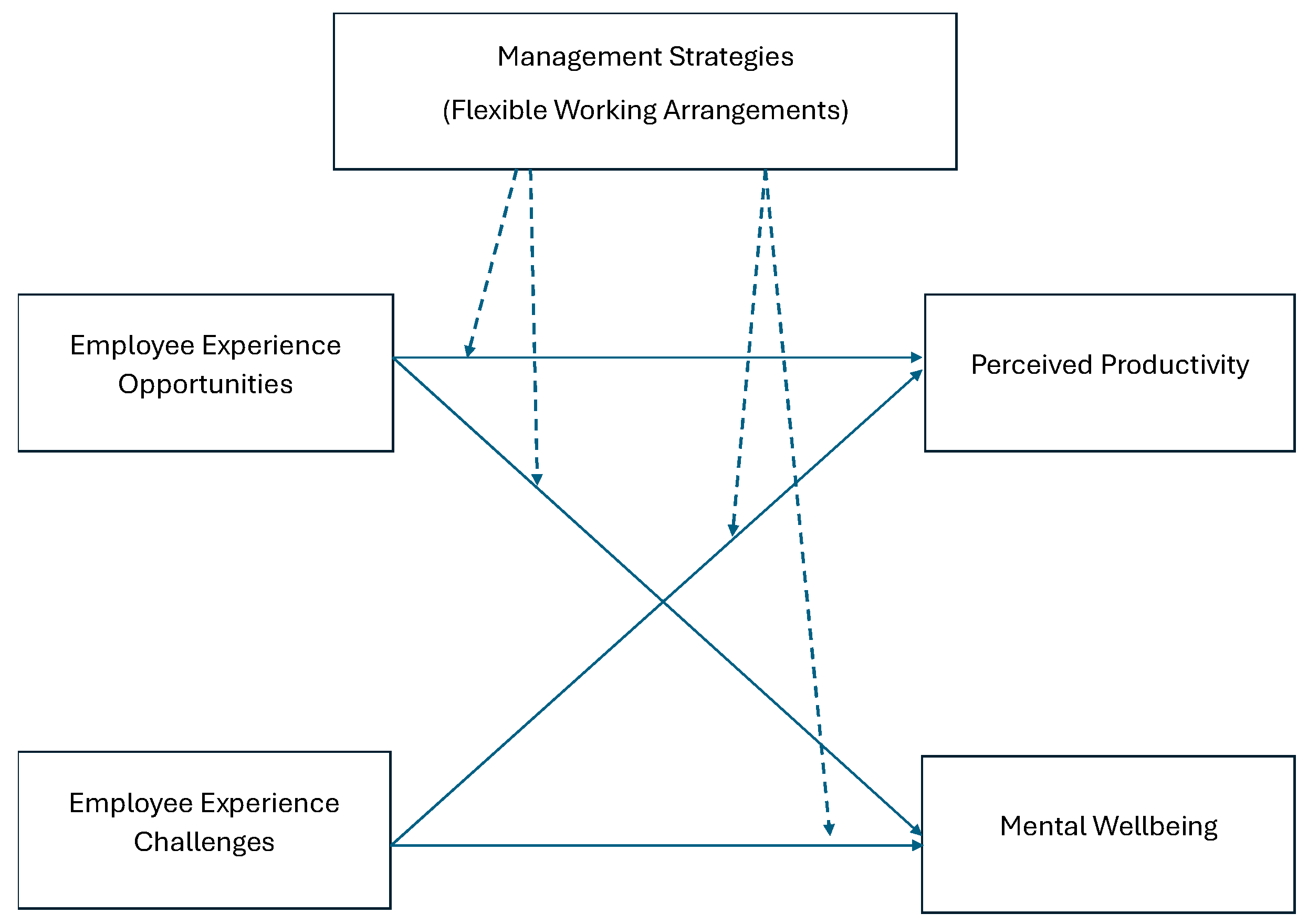

The following hypotheses guide the empirical analysis:

Hypothesis 1: EEOPP (Employee Experience–Opportunities) positively impacts PP.

Hypothesis 2: EECHALL (Employee Experience–Challenges) negatively impacts PP.

Hypothesis 3: MS (Management Strategies) strengthens the positive effect of EEOPP on PP.

Hypothesis 4: MS mitigates the negative effect of EECHALL on PP.

3. Research Design

3.1. Sample and Procedure

This method introduces certain limitations, including potential sampling bias, homogeneity among participants, and reduced generalisability due to the lack of industry-level stratification. These limitations should be considered when interpreting the findings.

Full ethics was granted for the study. Data were collected via snowball sampling, using social media and researcher connections over a six-week period. The survey platform used was Qualtrics, which is anonymous and confidential. Respondents are voluntary and the system ensures that each respondent can only complete the survey once. This method yielded a sample of 222 respondents. Demographics were obtained from the respondents, and qualifying questions were used to ensure that respondents were representative of the intended study population. The target participants for this study were individuals in New Zealand, specifically employees who prior to the COVID-19 pandemic had a traditional working arrangement (i.e., worked in an office, fully based at the organisation location, with set working hours), and while the questionnaire was in field, had the ability to work flexibly (i.e., located remotely and/or with flexible hours). Before the questionnaire was published, the questionnaire was piloted.

3.2. Measures

The survey tool comprised 16 demographic questions and 22 enquiring questions. Questions 1 to 16 sought respondent permission to undertake the survey, filtered out ineligible respondents as defined above and collected relevant demographic variables. Questions 17 to 19 enquired of respondents’ word demand and work autonomy practices on 5-point Likert scales from significantly increased to significantly decreased. A sample item is “How has your work demand changed since being able to work flexibly?” Questions 20 to 26 were measured on 5-point Likert scales from strongly disagree to strongly agree, asked about implementation of flexible working arrangements in the respondents’ organisation. A sample item is “My organisation has focused on alternative flexible work arrangements and emerging support technologies”. Questions 27 to 38 asked about how levels of productivity, collaboration, and communication had changed since the ability to work flexibly and were measured on 5-point Likert scales from much worse to much better. As sample item is “My task management and delivery performance”.

The perceived productivity construct is similar to the construct tested and used by researchers

Tanpipat et al. (

2021)-the questions were adapted to the current research study objective and the language altered to ensure the questions were suited for the target population (i.e., New Zealand). In

Tanpipat et al. (

2021), reliability and validity were confirmed. To ensure retention of the existing reliability and validity of the current study, scales were used in their entirety, with an exception to one construct, as modified items in multi-item scales reduces reliability and validity tested by the original researchers (

Tanpipat et al., 2021). Reliability tests were further taken to confirm the measures in this sample and the reliability coefficients for all the research constructs were above 0.75.

3.3. Analysis

In this analysis, we seek to test whether job resources map to predictors like perceived trust, flexibility, or support (shown in

Figure 2). Job demands may operationalize as distractions or blurred boundaries in remote work. SPSS (28.0 version) was used for analysing the survey data. 222 responses were received across a four-week period 46 surveys were significantly incomplete; these surveys were removed from the data and therefore only 176 responses were included in the analysis. The data analysis for this study consisted of a correlational and moderated regression research design (

Table 1) for the variables analysed. Following this, the moderated multiple regression strategy was conducted (

Stone-Romero & Anderson, 1994;

Zedeck, 1971).

The total responses received were 222; 46 (21%) of those responses were significantly incomplete with the final sample size coming to 176, for a total response completion rate of 79%. There were fewer male respondents (30%) than female respondents (70%). In terms of age group, the largest group of respondents were between the age of 26 and 40 years old (49%), with the second highest age group being 41–55 years old (36%). Majority of the respondents worked in the Finance and Insurance industry (48%), and 86% of respondents resided in the Auckland region. The population reported on in the study is representative of this sample.

In terms of respondents working flexibly in their organisation, 82% of respondents advised they had a formal flexible working arrangement in their organisation, 14% of respondents did not and 2% of respondents did not know/it was unknown to them whether their organisation had a formal FWA in place. The location where respondents mostly work was split fairly evenly between mostly working from their organisation’s office, 51%, and mostly working away from their organisation’s office, 49%.

4. Findings

4.1. Data Analysis and Results

Statistical significance (

p-value) for the study was defined as 0.05 (5%). For the test to be highly significant we use a

p-value of 0.01 (1%.) The

p-value for the test will need to be less than 0.05 to be significant at the 5% level. In interpreting participant responses, each impact was evaluated as an ordinal variable (

Table 2).

4.2. Work Demand

Respondents were asked two questions under the WD construct; for both questions, respondents were asked to think about their WD and work autonomy and how this has changed with a FWA versus when they had a traditional working arrangement in place.

64% of respondents advised their WD has remained the same, whereas 21% advised their WD has moderately increased and 10% advised their WD has significantly increased.

41% of respondents advised their work autonomy has remained the same, whereas 38% advised their work is moderately more autonomous and 19% advised their work is significantly more autonomous.

4.3. Employee Experiences and Perceived Productivity

EEOPP has a positive moderate correlation with PP (r = 0.610), results of regression indicated both variables explained 37% of the variance (R2 = 0.372). An analysis of variance showed a strong statistically significant relationship (F = 100.54, p ≤ 0.001). Std. Coefficients Beta (0.610) indicated a strong positive relationship.

EECHALL has a positive moderate correlation with PP (r = 0.515), results of regression indicated both variables explained 26% of the variance (R2 = 0.265). An analysis of variance showed a statistically significant relationship (F = 61.399, p ≤ 0.001). Std. Coefficients Beta (−0.525) indicated a strong negative relationship.

4.4. Employee Experiences and Management Strategy

EEOPP has a weak positive degree of correlation with MS (r = 0.015), results of regression indicated both variables explained 0% of the variance (R2 = 0.000), showing there is a very weak relationship between both variables. An analysis of variance showed a statistically insignificant relationship (F = 0.036, p = 0.850). Std. Coefficients Beta (−0.015) indicated a weak negative relationship.

EECHALL has a weak positive degree of correlation with MS (r = 0.040), results of regression indicated both variables explained 0% of the variance (R2 = 0.002), showing there is a very weak relationship between both variables. An analysis of variance showed a statistically insignificant relationship (F = 0.275, p = 0.601). Std. Coefficients Beta (−0.040) indicated a weak negative relationship.

The independent variables (EEOPP and MS) have a positive moderate degree of correlation with the dependent variable (PP) (r = 0.645), results of regression indicated all variables explained 41% of the variance (R

2 = 0.416). An analysis of variance showed a statistically significant relationship (F = 60.28,

p ≤ 0.001). There is a strong relationship between EEOPP and MS, and the relationship between EEOPP and PP is significant (

Table 3 and

Table 4).

MS, as the moderator, has a p-value of <0.001; since the p-value is lower than 0.05, we can consider that the moderator variable has an effect on the relationship between the independent variable, EEOPP, and the dependent variable, PP.

The independent variables (EECHALL and MS) have a positive moderate degree of correlation with the dependent variable (PP) (r = 0.546), results of regression indicated all variables explained 29% of the variance (R

2 = 0.299). An analysis of variance showed a statistically significant relationship (F = 35.95,

p ≤ 0.001). There is a strong relationship between EECHALL and MS, and the relationship between EECHALL and PP is significant (

Table 5 and

Table 6).

MS, as the moderator, has a

p-value of 0.005, since the

p-value is lower than 0.05, we can consider that the moderator variable has an effect on the relationship between the independent variable, EECHALL and the dependent variable, PP, see

Table 3.

4.5. Summary of Hypotheses H1 and H2: EE and Productivity

The hypotheses to predict the relationship between the variables of employee experiences and employee perceived productivity were both confirmed:

H1. EEOPP positively impacts PP.

H2. EECHALL negatively impacts PP.

Specifically, the independent variables, EEOPP and EECHALL, have a statistically significant relationship with the dependent variable, PP. The results indicate EEOPP has a strong positive relationship with PP, whereas EECHALL has a strong negative relationship with PP.

The results indicate employee experiences, expressed as opportunities, positively impact employee perceived productivity. This suggests that when employees have opportunities in an organisation, their perceived productivity is positively impacted. This relationship provides support for the JD-R model in relation to resources provided to employees. Those employees experiencing opportunities in an organisation, which may be due to resources provided by an organisation, has a positive impact on their perceived productivity.

Conversely, H2 suggests employee experiences, expressed as challenges, negatively impact employee perceived productivity. This suggests that when employees have challenges in an organisation, their perceived productivity is negatively impacted. This relationship provides support for the JD-R model in relation to job demands experienced by employees. Those employees experiencing challenges in an organisation, which may be due to job demands, has a negative impact on their perceived productivity.

The JD-R model emphasises the importance of organisational resources in ensuring employees feel supported and feel positive about their work (

Bakker & Demerouti, 2017). Positive experiences lead to positive work outcomes, and employee interests contribute to productivity (

Schaufeli & Bakker, 2004). When employees have adequate resources, they perceive the organisation’s interest in their work, resulting in a positive perception of their work and perceived productivity. However, when employees are not feeling supported, they may withdraw from their roles, especially when facing high job demands (

Demerouti et al., 2001). Without adequate resources, employees’ perceived productivity may be negatively impacted, as seen in H2, where negative experiences in the organisation, expressed as challenges, have a strong negative relationship with their perceived productivity.

Using the JD-R model as a theoretical framework to consider the findings, the confirmed hypotheses H1 and H2 support existing literature that employee experiences impact employee perceived productivity. Employee experience places employees at the centre of the organisation to examine factors of work and management practices that will enable employees to be successful or those that limit their ability to deliver on their responsibilities (

Luthans & Youssef-Morgan, 2017). Job resources can be motivational in themselves by supporting growth and learning or can be indirectly motivating by assisting employees in the achievement of work objectives, even during challenging times (

Demerouti & Bakker, 2011). Therefore, the hypothesised relationships and findings for H1 and H2 are supported by existing literature, specifically JD-R model.

4.6. Employee Experiences and Perceived Productivity, Moderated by Management Strategies

The relationships predicted between the independent variables, EEOPP and EECHALL, and the dependent variable, PP, were both confirmed to be statistically significant. The results indicated a strong positive relationship between EEOPP and PP (H1) and a strong negative relationship between EECHALL and PP (H2). With these relationships confirmed, the study further analysed the relationships with the intervention of a moderator variable, MS, and how the moderator variable might impact the relationships.

The hypotheses to predict the relationships between the variables of employee experiences and employee perceived productivity, moderated by MS, were both confirmed:

H3. MS has a more positive impact on the relationship between EEOPP and PP.

H4. MS has a less negative impact on the relationship between EECHALL and PP.

With the moderator variable, MS, the results show EEOPP has a stronger positive relationship with PP (H3), indicating the moderator variable significantly impacts the relationship between the independent and dependent variables. Similarly, with the moderator variable, MS, the results show that EECHALL has a less negative relationship with PP (H4).

The results indicate employee experiences, expressed as opportunities, have a stronger positive impact on employee perceived productivity when organisations make use of management strategies. This suggests that when employees have opportunities in an organisation, their perceived productivity is significantly impacted in a positive manner when organisations utilise FWAs as a management strategy. Conversely, H4 suggests employee experiences, expressed as challenges, have a less negative impact on employee perceived productivity when organisations make use of management strategies. This suggests that when employees have challenges in an organisation, their perceived productivity has a significantly less negative impact when organisations utilise FWAs as a management strategy.

5. Discussion and Implications

The JD-R model suggests that resources provided by an organisation are critical to employee support and productivity. Our findings extend this framework by showing that management strategies further moderate these effects, aligning with and building upon recent work (e.g.,

Bakker & Demerouti, 2017;

Bilotta et al., 2021).

This is particularly relevant when employees are experiencing high job demands. Job demands of an organisation can cause employees to jeopardise their mental wellbeing, which can negatively impact their work life balance. The JD-R model has a health-protecting factor known as job resources that can reduce the negative health effects of job demands. Job resources play a motivational role, stimulate work engagement and foster positive organisational outcomes. When employees are supported with organisational resources, the negative impacts of job demands can be reduced, which will have a positive impact on employee mental wellbeing.

The JD-R model supports existing literature that employee experiences impact perceived productivity and mental wellbeing. The results for H1 and H2 confirm the literature, indicating a strong positive relationship between EEOPP and PP (H1) and a strong negative relationship between EECHALL and PP (H2).

The research findings support existing literature, that if organisations cannot provide sufficient resources to support employees, especially during challenging times, organisations could consider using FWAs as a management strategy to help moderate the relationship between employee experiences and perceived productivity, and employee experiences and mental wellbeing.

JD-R model provided a lens for a deeper understanding of the research question. The JD-R model, driven by job demands and resources of the organisation, provides insight to better understand the relationship between employees and management. Both frameworks demonstrate the ongoing interaction between organisations and their employees and are particularly useful in providing guidance to organisations by drawing on decades of research to identify effective strategies for the organisation.

The findings of this study provide clear answers to the impact of FWAs, as a management strategy, moderating the relationship between employee experiences and perceived productivity and mental wellbeing. If organisations look at utilising FWAs, they can influence the impact of employee experiences on employee perceived productivity and mental wellbeing.

6. Conclusions

This research investigates the relationship between flexible working arrangements (FWAs), employee experiences (EE), and perceived productivity (PP) within New Zealand workplaces, drawing on the Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model. Through a survey of 176 employees, the study examines how FWAs influence autonomy, work demands, and perceived productivity. The findings (see

Table 7) indicate that employee experiences framed as opportunities (EEOPP) are positively associated with productivity, while those framed as challenges (EECHALL) show a negative correlation. Furthermore, management strategies (MS) were found to play a significant moderating role, enhancing the positive effects of EEOPP and mitigating the negative impact of EECHALL on productivity.

These findings reinforce and extend the JD-R framework by demonstrating that FWAs can serve as strategic resources when implemented thoughtfully. Rather than being viewed simply as accommodations, FWAs should be recognised as tools that managers can use to proactively shape employee experiences and drive performance. Managers can leverage FWAs strategically by fostering autonomy, providing clarity around expectations, ensuring consistent communication, and offering targeted support for remote or hybrid workers. For instance, establishing regular check-ins, supporting flexible scheduling within performance boundaries, and ensuring access to appropriate technology can significantly enhance employee wellbeing and output.

At the policy level, organisations must move beyond ad hoc approaches to flexible work and invest in formalised support structures. This includes developing clear FWA policies that define eligibility, expectations, and support mechanisms. Organisations should institutionalise training programmes for managers to lead hybrid teams effectively, ensure ergonomic and digital support for remote workers, and build a culture of trust and accountability. National policy frameworks could further support this by offering guidance on remote work standards, incentivising inclusive FWA policies, and ensuring legal protections around flexibility, equity, and worker wellbeing.

This study is subject to several limitations. First, it relies on self-reported data, which may be influenced by response bias or social desirability effects. Future studies could benefit from incorporating multi-source data—such as supervisor assessments, performance metrics, or observational data—to validate and triangulate findings. Second, the cross-sectional design limits the ability to draw causal inferences or assess how FWAs influence employee outcomes over time. Longitudinal research is needed to explore the long-term effects of FWAs on productivity, engagement, and wellbeing, particularly in evolving hybrid work contexts.

Finally, this study was conducted within a New Zealand context, and cultural or institutional factors may shape the generalisability of the findings. Comparative research across different countries or regions could offer valuable insights into how cultural values, employment legislation, and managerial norms interact with flexible work practices. Future studies should examine how FWAs function in diverse organisational and cultural settings, enabling a more global understanding of their efficacy and challenges.