1. Introduction

The intensive development of Arctic hydrocarbon resources, particularly on the Yamal Peninsula and the adjacent shelf, is a strategic priority [

1,

2]. Constructing technological platforms in the cryolithozone represents one of the most complex engineering challenges, especially in northern regions where the base consists of permafrost rocks [

3,

4]. The stability of these rocks is threatened by global climate changes leading to permafrost degradation (a process involving rising rock temperatures, thawing, and an increase in the active layer depth), which consequently causes a loss of foundation bearing capacity [

5,

6]. Thus, the reliability and durability of infrastructure directly depend on the complex interaction between the structure and the rock mass, requiring deep deformation analysis and system stability assessment [

7,

8,

9].

Permafrost rocks constitute a complex multicomponent system whose mechanical properties differ fundamentally from thawed rocks [

10,

11]. Their behavior is determined by factors such as temperature, ice content, unfrozen water content, and mineral composition [

12]. Under long-term loading, they exhibit pronounced rheological properties [

13,

14,

15], necessitating specific design approaches [

16,

17,

18]. Saline frozen rocks present particular complexity; the presence of salts significantly alters the phase composition of water, reduces strength, and increases rock deformability at negative temperatures [

19,

20].

Accurate determination of thermal and physical properties is crucial for the long-term reliability of foundations in cold regions. It is established that porosity and saturation are dominant variables controlling heat transfer [

21], allowing for the effective quantification of frozen soil thermal conductivity based on basic physical properties [

22]. Furthermore, parameters such as volumetric ice content and temperature are critical for predicting mechanical interface behavior and frost jacking performance [

23]. These findings underscore the importance of correctly accounting for the physical state of the ground when selecting design parameters for permafrost foundations.

Although pile foundations are widely used in permafrost conditions, traditional installation approaches face several technological and operational limitations [

24,

25,

26]. First, current practices for installing pile foundations in frozen rocks with large inclusions involve high labor intensity and increased wear on drilling tools [

27]. The presence of boulders can halt the drilling process, increasing construction time and costs.

Second, drilling without continuous casing carries a high risk of water-saturated seasonal layer soil ingress into the pile body. This reduces bearing capacity [

28,

29], leads to uneven settlement, and increases deformation risks during operation [

30,

31,

32].

Third, most existing technologies for pile foundations in the cryolithozone do not account for the full life cycle of the structure and lack provisions for dismantling after the service life ends [

33]. Often, the cost of dismantling and disposal exceeds the initial installation costs. Furthermore, forceful extraction often breaks the piles, complicating site remediation. Such approaches fail to minimize environmental impact [

34] or ensure the economic efficiency required for sustainable Arctic development [

35].

To address these challenges, the present study proposes a solution derived from the practical experience of one of the authors gained during the installation of sheet piles using simultaneous casing drilling (Symmetrix type) in Yakutia. While the drilling operations were successfully executed, it was observed that the rigorous climatic conditions and prolonged periods of negative air temperatures severely restricted the time window available for internal pile concreting. Given that the casing installation technology itself precludes “wet” processes, a concept was developed to extend the construction season into the colder months by eliminating the concreting stage. To achieve this without compromising the structural performance, a novel “dome-plug” (PDP) element was introduced to maintain the pile’s bearing capacity [

36]. The detailed geomechanical justification of this technology is the subject of the present research.

2. Materials and Methods

The study investigates the bearing capacity and efficiency of a novel method for constructing pile foundations in permafrost conditions. The proposed method is based on an advanced drilling technology with simultaneous casing, the key element of which is the installation of a lockable dome-plug (PDP). This element effectively transforms the shell pile into a fully functional pile-column [

36].

Pile installation is performed using a method typically employed for steel casing pipes—drilling the borehole with simultaneous immersion of the casing. Originally introduced by Atlas Copco (Nacka, Sweden), this method has been adopted and technically modified by other international manufacturers (e.g., Robit OY, Lempäälä, Finland) [

37]. A distinctive feature of this technology is the capability to install casing pipes in soils and rocks of any drillability category—from soft-plastic to hard rocks, including thawed, water-saturated, and frozen grounds, as well as in bottom sediments of water bodies. Currently, drilling tools for this method are available for casing diameters ranging from 114 to 1500 mm.

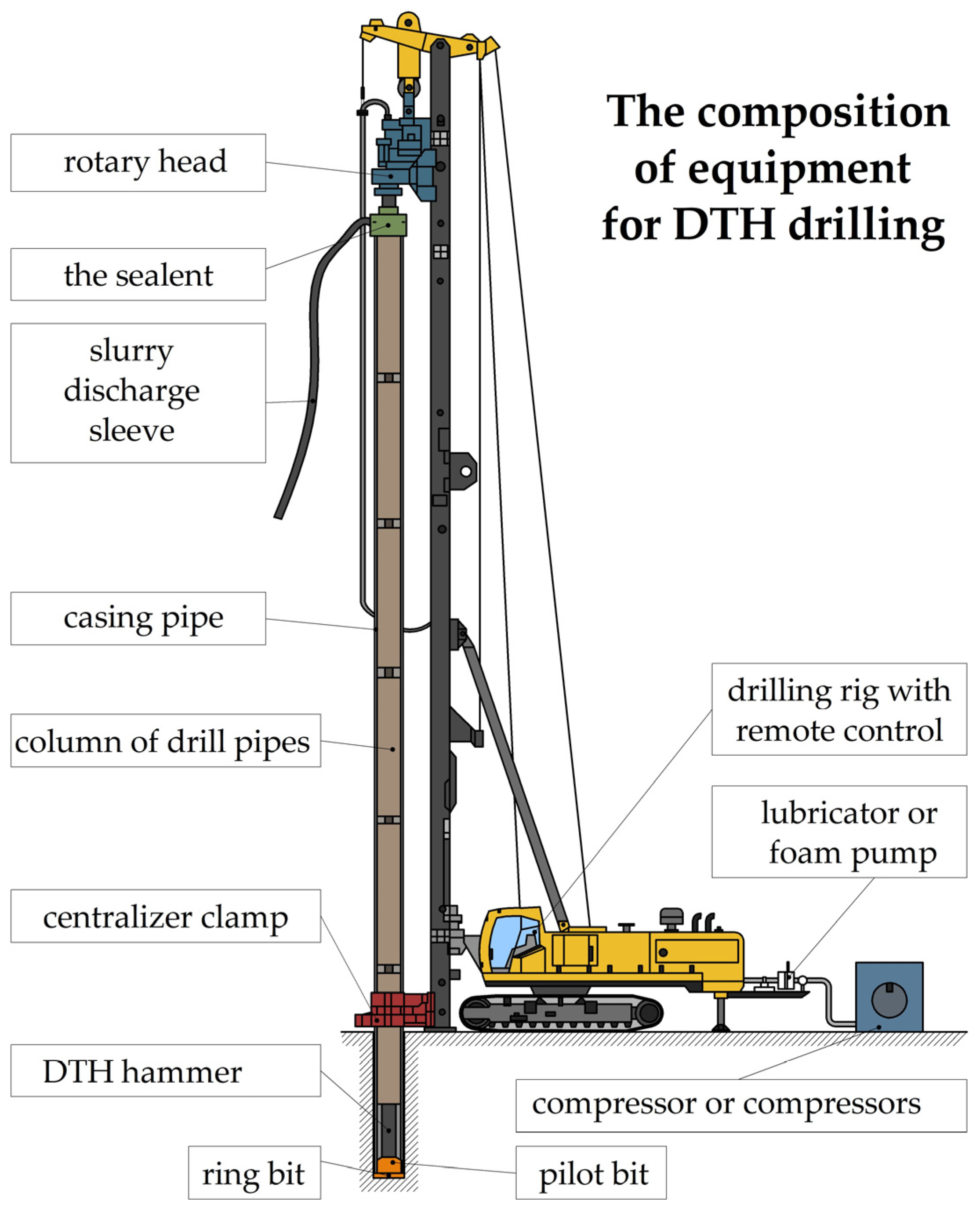

The workflow for this technology is shown in

Figure 1.

The casing installation proceeds in the following sequence:

At the first stage, the drill string, consisting of drill rods, a down-the-hole (DTH) hammer, and a pilot bit, is assembled and connected to the drilling rig rotator. The ring bit is joined to the casing pipe using a welded connection. With the rig mast in a horizontal position, the casing is pulled onto the drill string until the shoulders of the pilot bit abut against the internal diametric protrusion of the ring bit. The rig centralizer is then clamped to secure the casing and drilling tool assembly on the mast. Subsequently, the mast is raised to a vertical position and lowered until the drilling tool and casing contact the ground. The compressor is activated, supplying compressed air through the hose to the rotator swivel. Percussive-rotary drilling is then performed with simultaneous immersion of the casing pipe to the design depth. During this process, rotation from the rig drive is transmitted through the drill rods to the DTH hammer and the pilot bit secured within it. Due to the right-hand rotation of the drill string, the pilot bit, engaged in a bayonet connection with the ring bit, performs simultaneous drilling and reaming of the borehole, ensuring casing immersion under the impact impulses of the DTH hammer. The compressed air flow powers the DTH hammer, cleans the pilot bit, and transports cuttings to the surface through the gap between the drill rods and the inner surface of the casing. To ensure the discharge of the air-cuttings flow onto the ground, a discharge head with a hose is employed. Penetration through thawed soils and permafrost rocks is carried out under the protection of the casing pipe, preventing the collapse of the borehole walls. The minimal annular gap (5–10 mm) between the immersed casing and the borehole walls is filled during drilling with a portion of the drill cuttings and, potentially, water from overlying thawed soils. Furthermore, during the immersion of the casing pipes, vibration from the operation of the DTH hammer is transmitted to them, which contributes to the compaction of the slurry in the annular space of the future pile-column.

At the second stage of execution, after reaching the design depth of the casing immersion, the drill string is rotated one or two turns to the left; this disengages the bayonet connection between the pilot bit and the ring bit, and the drill string is retrieved from the borehole. The casing pipe, with the ring bit installed at its lower part, remains in the borehole at the design elevation.

At the third stage of the work, the internal cavity of the casing pipe may be filled with concrete mixture only in the bottom section for 1–2 m or for the full length, depending on the design solution.

To address the specific challenges of permafrost foundations, the standard technology described above was modified. Instead of filling the casing with concrete (a “wet” process), a specialized dome-plug is installed. To demonstrate the fundamental differences and advantages of the developed technology, a comparative analysis was performed (

Table 1) [

38,

39,

40].

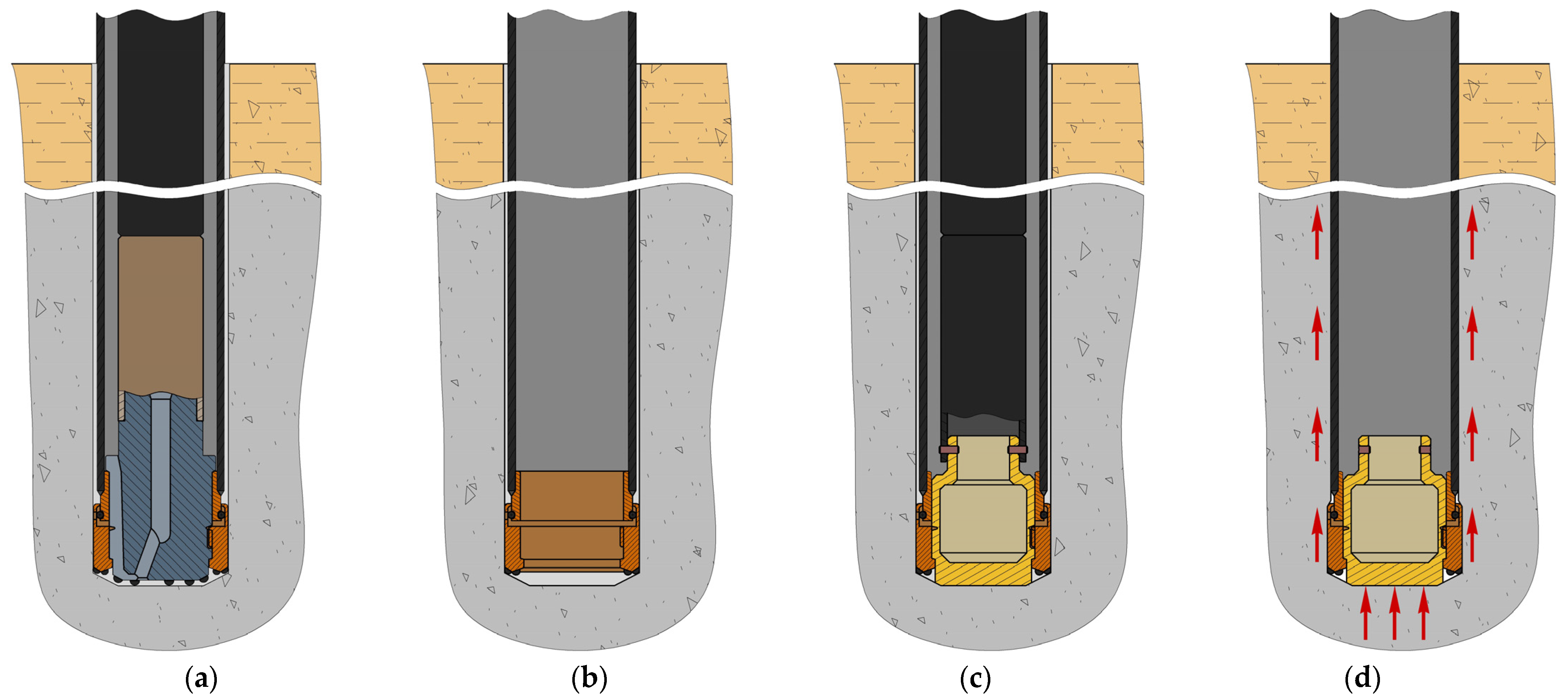

The comparison confirms that the proposed pile with a dome-plug eliminates the main drawbacks of traditional technologies while combining their advantages. The key stages of the proposed technology, distinguishing it from the standard approach, are illustrated in

Figure 2.

The proposed method [

36] prevents the ingress of water-saturated and thawed soils into the pile cavity. After the drilling tool is removed, the dome-plug is lowered and fixed via a bayonet connection at the bottom of the casing. The structure is then left to freeze with the surrounding rock mass, forming a unified bearing system.

One of the potential applications of the proposed shell pile technology is to serve as a bearing element for flexible and cost-effective modular technological platforms. The concept of such platforms [

44] involves constructing facilities from standardized modules (e.g., 6 × 6 m or 9 × 9 m), which are sequentially connected into a single large-area structure using quick-release hinged connections.

A critical feature of the design is its reversibility. If dismantling is required, a heating element is lowered into the hollow pile shaft. Heat transfer through the steel casing thaws the surrounding rock interface. Once thawed, the entire pile, including the dome-plug, can be extracted with standard lifting equipment, ensuring minimal environmental impact and allowing for reusability.

To evaluate the bearing capacity and analyze the stress–strain state (SSS) of the “pile-soil” system, numerical modeling was performed using the Finite Element Method (FEM) [

45,

46,

47]. This method allows for the consideration of complex geometry, nonlinear material behavior, and contact interaction at the “pile-soil” interface.

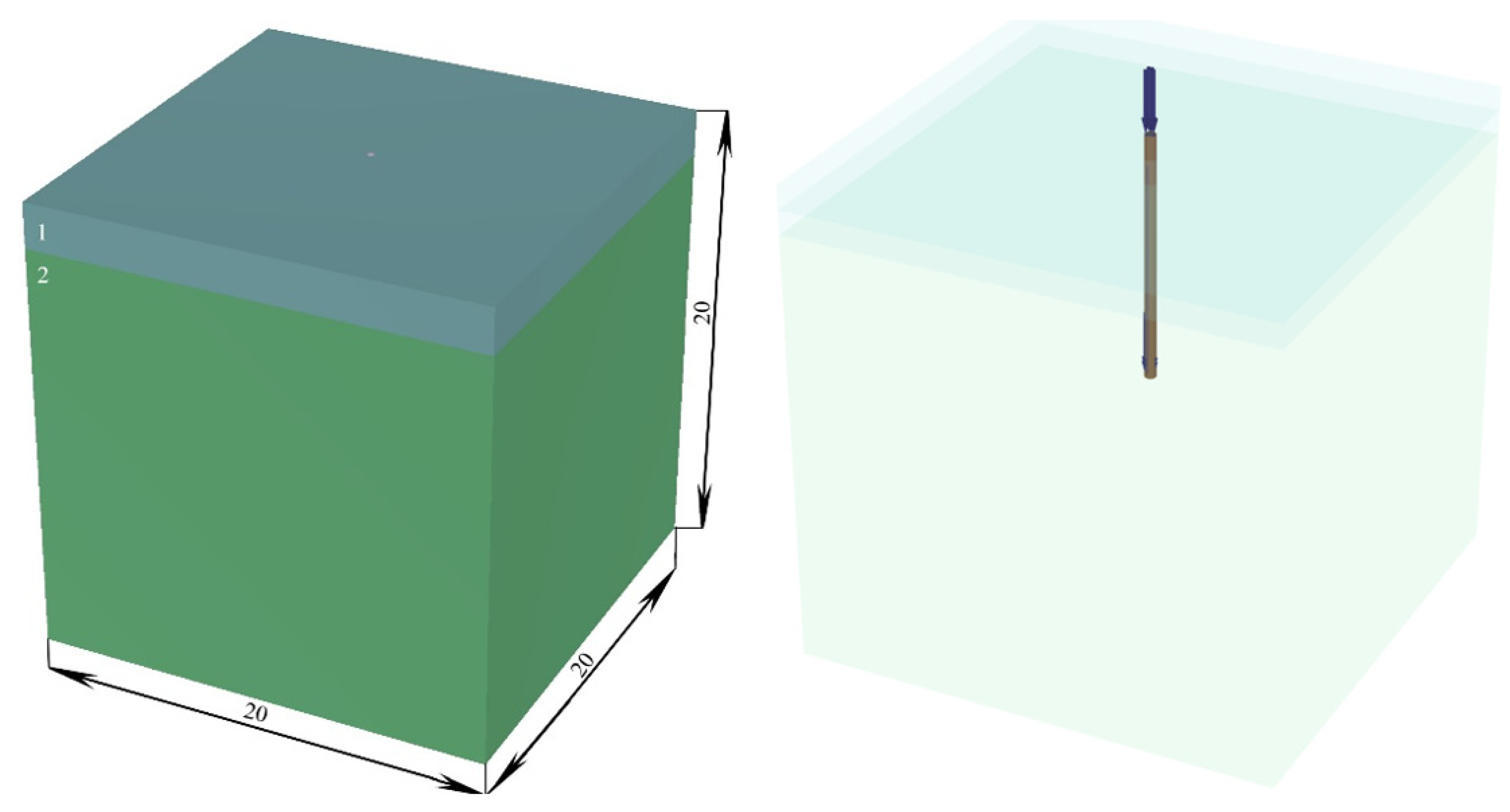

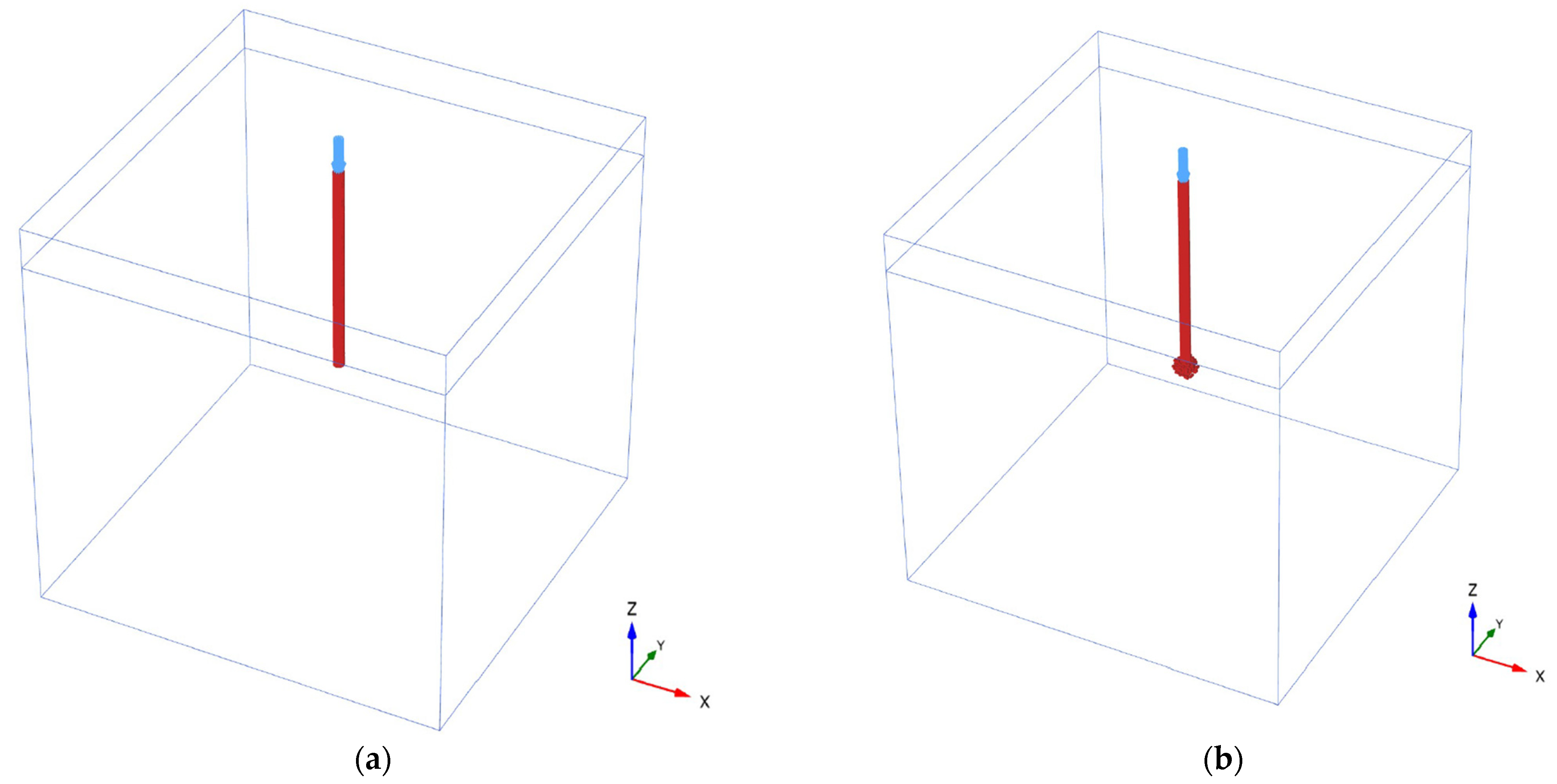

The simulation was conducted using the Plaxis 3D 2021 geotechnical software suite. A three-dimensional spatial model with dimensions of 20 × 20 × 20 m was created, representing a representative volume of the rock mass with a single pile located in its center (

Figure 3).

The model geometry includes a pile with a diameter of 325 mm and a length of 10 m. This diameter was selected to correspond to standard casing sizes compatible with Symmetrix-type drilling systems. The pile is installed in a two-layer base consisting of a seasonally thawing active layer (2 m thick) and an underlying permafrost layer.

For model discretization, a finite element mesh consisting of 10-node tetrahedral elements was used. To improve result accuracy, the mesh was significantly refined in the zone adjacent to the pile, where the highest stress and strain gradients are expected, with a gradual coarsening of elements towards the model boundaries.

Interaction at the “pile-soil” interface was modeled using special 16-node interface elements. The strength properties of the interface (cohesion and friction) were defined based on the rock properties using a standard reduction factor for permafrost,

Rinter = 0.75 [

48]. This coefficient reflects the reduced freezing strength compared to the monolithic rocks.

Numerical convergence at each loading step was controlled by a standard criterion based on the normalized unbalanced force. In this context, the calculation was considered converged when this norm fell below 0.01, ensuring high accuracy and reliability of the obtained results.

The problem involved analyzing the SSS of a frozen rock mass under static vertical loading. Thermal processes were accounted for implicitly through the physical-mechanical properties of the frozen and thawed soils. To ensure a high degree of reliability, input parameters were based on the authors’ own experimental studies conducted on frozen rock samples from the Yamal Peninsula. The methodology for determining long-term strength and deformation characteristics, along with full results, has been published previously [

49]. The design temperature of the permafrost was set to −3 °C.

The constitutive models and input parameters used for the seasonally thawing layer, the permafrost layer, and the pile material are detailed in

Table 2,

Table 3 and

Table 4. Average values characteristic of saline and non-saline rocks (clays, loams, and sandy loams) were selected for modeling from the range of experimentally obtained data (

Table 2,

Table 3 and

Table 4).

Although the Mohr–Coulomb model does not explicitly describe creep processes characteristic of frozen rocks [

51,

52,

53], this effect is accounted for implicitly. The approach involves replacing complex time-dependent thermo-viscoplastic analysis with a quasi-static calculation using long-term strength and deformation characteristics. These parameters correspond to the stabilized stage of rock deformation, which is a standard practice for assessing long-term stability. The input parameters used are based on a series of long-term laboratory tests on Yamal samples [

49]. This method provides a conservative estimate of bearing capacity (i.e., the minimum value at the end of the service life), fully meeting safety design objectives.

The calculation was performed sequentially in several stages: generation of the initial stress state in the rock mass, creation of the borehole with casing installation, installation of the dome-plug (activation of the plug volume), application of step-wise increasing vertical load to the pile head.

The loading procedure was designed to construct the full “load-settlement” curve and determine the ultimate bearing capacity. Initially, a load corresponding to a stress of 1 MPa was applied to simulate initial operating conditions and stabilize the numerical solution. Subsequently, a progressively increasing load was applied. In the solver settings, a target stress value exceeding 100 MPa was specified. This value was set solely to guarantee that the numerical model reaches a state of mathematical failure and does not represent an actual physical load applied to the structure. The actual ultimate bearing capacity of the pile was defined as the maximum load reached at the last calculation step before the loss of numerical convergence.

3. Results

Numerical modeling was conducted to systematically analyze and compare the bearing capacity of the proposed Pile with Dome-Plug (PDP) and the prototype Pile Without Dome-Plug (PWDP) under various engineering-geological conditions characteristic of the Yamal Peninsula.

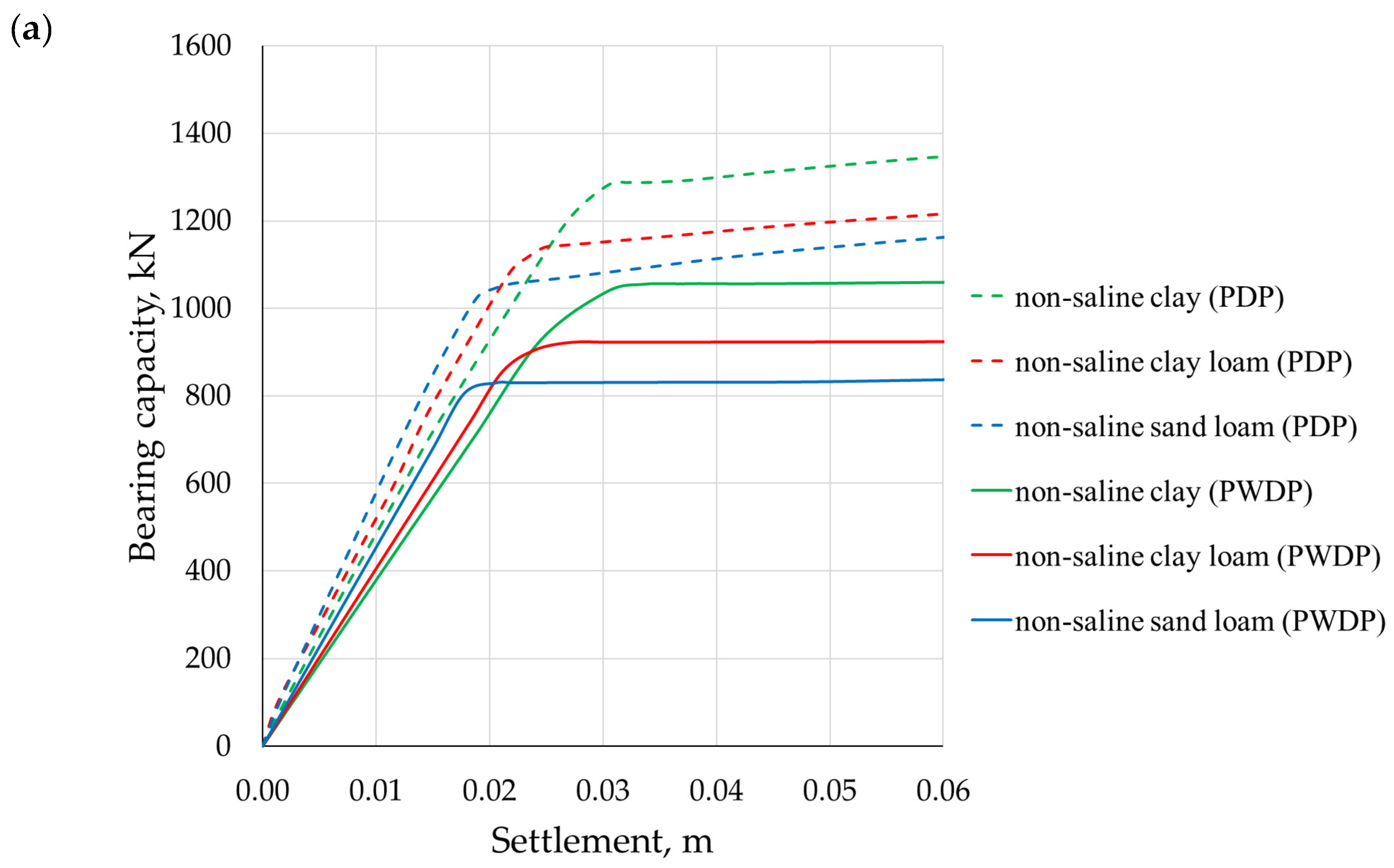

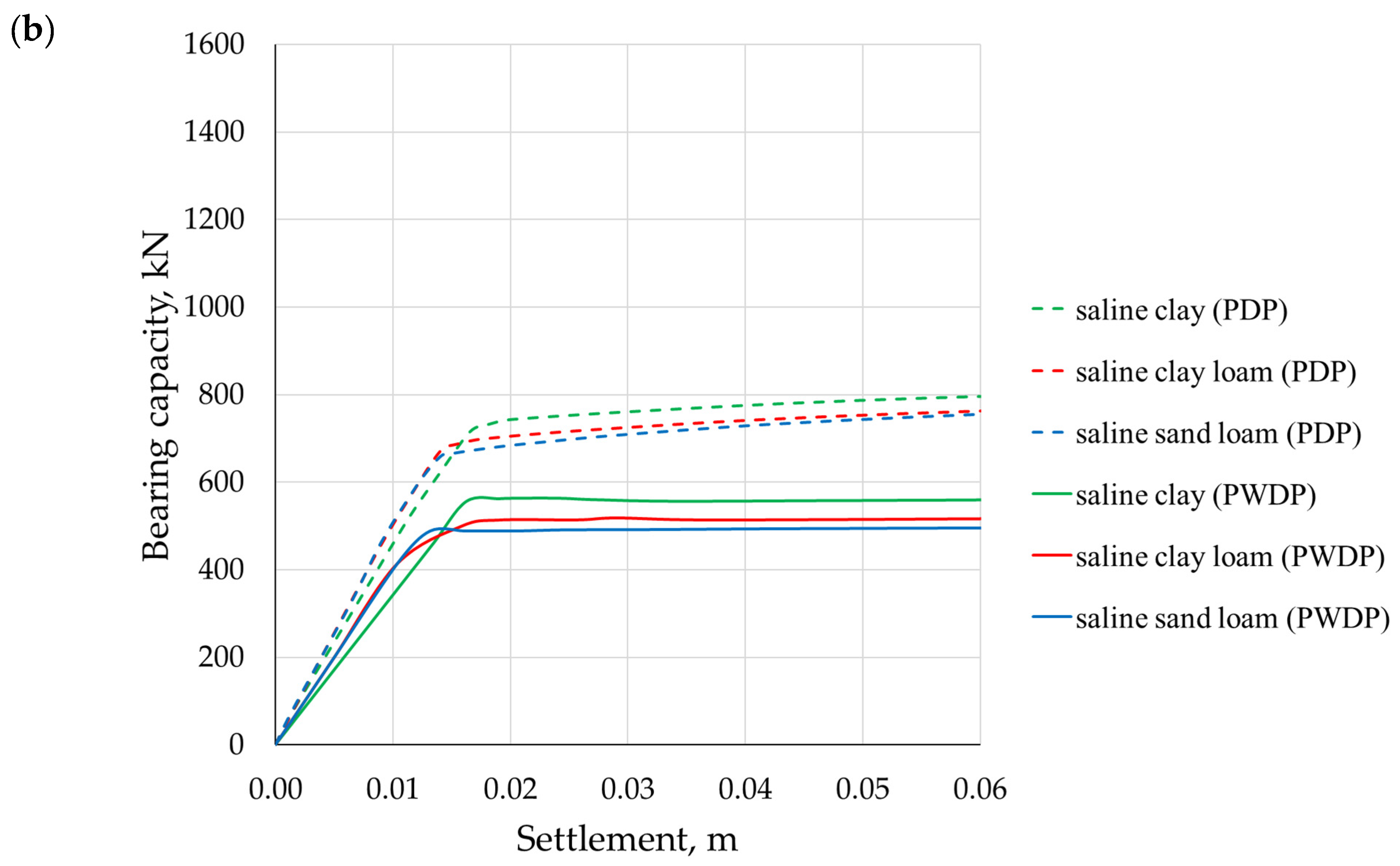

The primary results of the modeling are the “load-settlement” curves presented in

Figure 4. All obtained curves exhibit a pronounced elastoplastic character, transitioning to a state of plastic flow upon reaching the ultimate load.

Analyzing the shape of the obtained curves, it is necessary to explicitly explain the observed hardening phase for the PDP (

Figure 4). This effect reflects the structural response of the “pile-rock” system. It can be described as a sequential mobilization of resistance mechanisms. At the initial stages of loading, the shear strength (adfreezing bond) along the lateral surface of the pile is primarily mobilized. With further settlement, the dome-plug gradually engages, activating the bearing capacity of the rocks beneath the pile toe. As a result, this staged engagement of different resistance components manifests on the integral graph as a phase of gradual load increase.

The analysis of these relationships leads to the following key observations:

To provide a precise quantitative evaluation of the proposed solution’s efficiency, the ultimate bearing capacities determined from the graphs are summarized in

Table 5.

The results reveal distinct patterns in how rock properties influence the bearing capacity for both pile types. In all considered cases, a consistent reduction in capacity is observed in the lithological sequence: Clay → Loam → Sandy Loam. Furthermore, the installation of the dome-plug provides a universal increase in bearing capacity across all soil types, ranging from 35.2% to 63.3%.

To evaluate the relative impact of geological factors, a quantitative sensitivity analysis was performed based on the data in

Table 5. The analysis indicates that salinity is the dominant factor governing pile performance. Transitioning from non-saline to saline conditions results in a sharp reduction in bearing capacity: approximately 41% for clays (from 1420 to 830 kN) and 36% for sandy loams. In contrast, the lithological type has a moderate impact; for piles with a dome-plug in non-saline conditions, changing the soil matrix from clay to sandy loam results in only a 12% decrease (from 1420 to 1250 kN).

Crucially, while salinity significantly degrades the absolute bearing capacity, the proposed technology demonstrates its highest relative efficiency precisely in these adverse conditions. The maximum relative improvement (+48.2% to +63.3%) is observed in the weakest saline rocks. This confirms that the dome-plug effectively compensates for the loss of shear strength along the pile shaft, making it a particularly valuable solution for complex geocryological conditions where traditional friction piles lose nearly half of their capacity.

To quantitatively confirm the transformation of the pile’s working mechanism, an analysis of load distribution at the ultimate limit state was performed. By integrating shear stresses along the pile shaft and normal stresses across the pile toe, their respective contributions to the total bearing capacity were determined (

Table 6).

Data analysis shows that the plug-heel perceives and transfers 41.3% to 45.4% of the total applied load to the base. The load distribution mechanism demonstrates high stability across different soil types, indicating the reliability of the proposed design in various geocryological conditions.

To visually confirm the quantitative data from

Table 5 and illustrate the fundamental differences in the pile working mechanisms,

Figure 5 shows the distribution of plastic flow points in the rock mass at the moment of ultimate loading.

In the PWDP model (

Figure 5a), plastic points in the area of the lower toe are practically absent. This implies that the permafrost rocks beneath the pile remain in the elastic stage and do not carry significant load; failure occurs due to the exhaustion of bearing capacity along the lateral surface. Conversely, in the PDP model (

Figure 5b), the formation of a clearly defined zone of plastic flow (a “plastic bulb”) is observed directly beneath the heel. This confirms the transfer of a significant portion of the load through the plug to the base. Thus, the visual analysis corroborates the quantitative data and substantiates the conclusion that the shell pile is transformed into a combined pile-column.

4. Discussion

The modeling results demonstrate the high efficiency of the proposed pile as a primary load-bearing element for modular technological platforms. The high bearing capacity allows for the optimization of the pile grid under standard modules (6 × 6 m or 9 × 9 m), ensuring reliable support for drilling and auxiliary equipment loads.

The application of the Dome-Plug, installed at the bottom of the casing, ensures load redistribution and active engagement of the Pile Base in resisting vertical loads. This is a key distinction from traditional bored and driven cast-in situ piles [

54,

55], where shaft adfreezing plays the dominant role.

Analysis of force distribution showed that the Pile Base actively engages the underlying permafrost, taking up to 45.4% of the total load. This effect is particularly critical in weak, saline rocks, where the relative increase in bearing capacity reaches its maximum, compensating for reduced shear resistance along the lateral surface. The efficiency is further enhanced by the simultaneous casing drilling method, which guarantees superior contact between the pile and undisturbed frozen rocks. This allows for the full realization of adfreezing strength at the “pile-soil” interface, a critical parameter for all pile types in the cryolithozone [

29,

56].

Technologically, the method offers a distinct advantage for Arctic conditions by relying on the assembly of prefabricated steel elements. This eliminates temperature-sensitive “wet” concrete works, making the technology highly adaptable to the harsh Arctic climate.

A comparison of results across six different permafrost types confirms a direct correlation between bearing capacity and the strength/deformability of the rocks. Special note should be made of the temperature influence, which was kept constant at −3 °C in the model. It can be predicted that at lower temperatures, bearing capacity will increase, while at temperatures near 0 °C, it will significantly decrease [

57,

58]. This underscores the importance of precise thermal regime consideration during design.

Regarding the long-term behavior of the foundation, it is important to note the specific approach taken to model creep effects. While the Mohr–Coulomb model does not explicitly simulate time-dependent viscoplastic flow, this study adopted a quasi-static approach by utilizing long-term strength parameters derived from laboratory creep tests. These parameters correspond to the stabilized state of the rock mass, effectively representing the lower bound of bearing capacity at the end of the structure’s service life. Thus, the model provides a conservative estimate suitable for safety assessments, implicitly accounting for the reduction in strength due to rheological processes.

A key advantage of the proposed design, meeting modern requirements for the full life cycle of facilities, is its fundamental capability for complete and environmentally safe dismantling. Unlike monolithic reinforced concrete piles, extraction of which requires immense force and often leads to breakage, the proposed technology utilizes a hollow shell structure.

The dismantling process involves lowering a heating element (e.g., a heating cable or heat carrier system) inside the pile. Heat transfer through the steel wall to the “pile-soil” interface causes local thawing of a thin permafrost layer along the pile contour, effectively destroying adfreezing forces.

To validate the feasibility of complete extraction, a pull-out force analysis was performed. The calculation assumed that the permafrost along the entire pile length is artificially thawed, with properties corresponding to the seasonally thawing layer (

Table 2). Calculating the pull-out resistance (equal to skin friction in the thawed state) using standard soil mechanics methods showed that the maximum required force is approximately 490–520 kN. This force is significantly lower than the pile’s bearing capacity in the frozen state (800–1420 kN) and falls well within the technical capabilities of standard crane equipment.

The mechanics of this dismantling process can be further understood in the context of recent thermo-mechanical models [

23], which demonstrate that the pile–soil interface exhibits strain-softening behavior heavily dependent on temperature and normal stress. While frost jacking forces rely on the high shear strength of the frozen interface at negative temperatures, the proposed dismantling technology exploits the inverse of this relationship. By artificially raising the interface temperature above 0 °C, the adfreeze bond is destroyed, and the shear strength drops to the residual friction of thawed soil. Furthermore, the dome-plug geometry fundamentally alters the pile-soil interaction compared to conventional piles described in such models [

23]. By engaging the compressive strength of the frozen soil at the pile toe (providing ~45% of total resistance), the system reduces reliance on the shaft interface, thereby mitigating the risks associated with interface creep and degradation of adfreezing bonds over time.

This approach is far more eco-friendly than cutting off pile heads and leaving concrete or steel bodies in the permafrost. It confirms the high potential of the technology for creating fully dismantling foundations, minimizing impact on the fragile Arctic ecosystem.

The achieved high bearing capacity makes these piles optimal for modular platforms [

59]. The possibility of year-round installation and complete dismantling offers an economically and ecologically effective alternative to constructing artificial islands [

60].

Furthermore, the hollow construction opens perspectives for creating thermo-active foundations capable of artificially maintaining the frozen state of the base [

61,

62]. According to experimental data [

60], placing a coolant (e.g., solid carbon dioxide) inside such hollow piles allows for the formation of an ice cylinder with a radius of up to 2 m around each pile within 5–10 days. This enables the creation of a continuous reinforced ice-soil base capable of withstanding significant lateral ice loads on the shallow shelf. Thus, the solution addresses the lack of sand quarries, eliminates risks associated with seasonal flooding, and can reduce costs by up to 5 times [

60], while also complementing thermal stabilization technologies.

While this study provides a solid geomechanical justification, it has limitations that define future research directions: detailed analysis of frost heave forces requires separate thermo-mechanical modeling; to predict deformations over time, more complex viscoplastic models [

63,

64] should be employed; detailed structural design of the Dome-Plug and in-depth stress analysis of the steel components are separate tasks for future engineering studies; the obtained numerical results require validation through laboratory and field tests.

Despite these limitations, this research provides a reliable theoretical basis proving the high potential of the proposed technology.