Pore Ice Content and Unfrozen Water Content Coexistence in Partially Frozen Soils: A State-of-the-Art Review of Mechanisms, Measurement Technology and Modeling Methods

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Thermodynamics and Micro-Scale Pore Ice–Water Dynamics

- (i)

- Stage I (0 to –5 °C): Ice nucleates in large pores and there is rapid UWC drop.

- (ii)

- Stage II (–5 to –15 °C): Ice fills medium/small pores and solute concentration rises.

- (iii)

- Stage III (<–15 °C): UWC stabilizes as thin adsorbed films.

2.1. Premelting Theory and Disjoining Pressure

- (i)

- Curvature-induced premelting: Supercooled liquid water remains in micropores due to capillary effects and surface tension, analogous to cryogenic suction in unsaturated soils.

- (ii)

- Interfacial premelting: Thin water films form at ice–soil interfaces, driven by reductions in interfacial energy and thermal gradients, where the film on the colder side of the soil is thinner than that on the warmer side [31].

- (i)

- Adsorption layer, dominated by van der Waals and electrostatic forces.

- (ii)

- Diffuse layer, controlled primarily by electrostatic repulsion.

- (i)

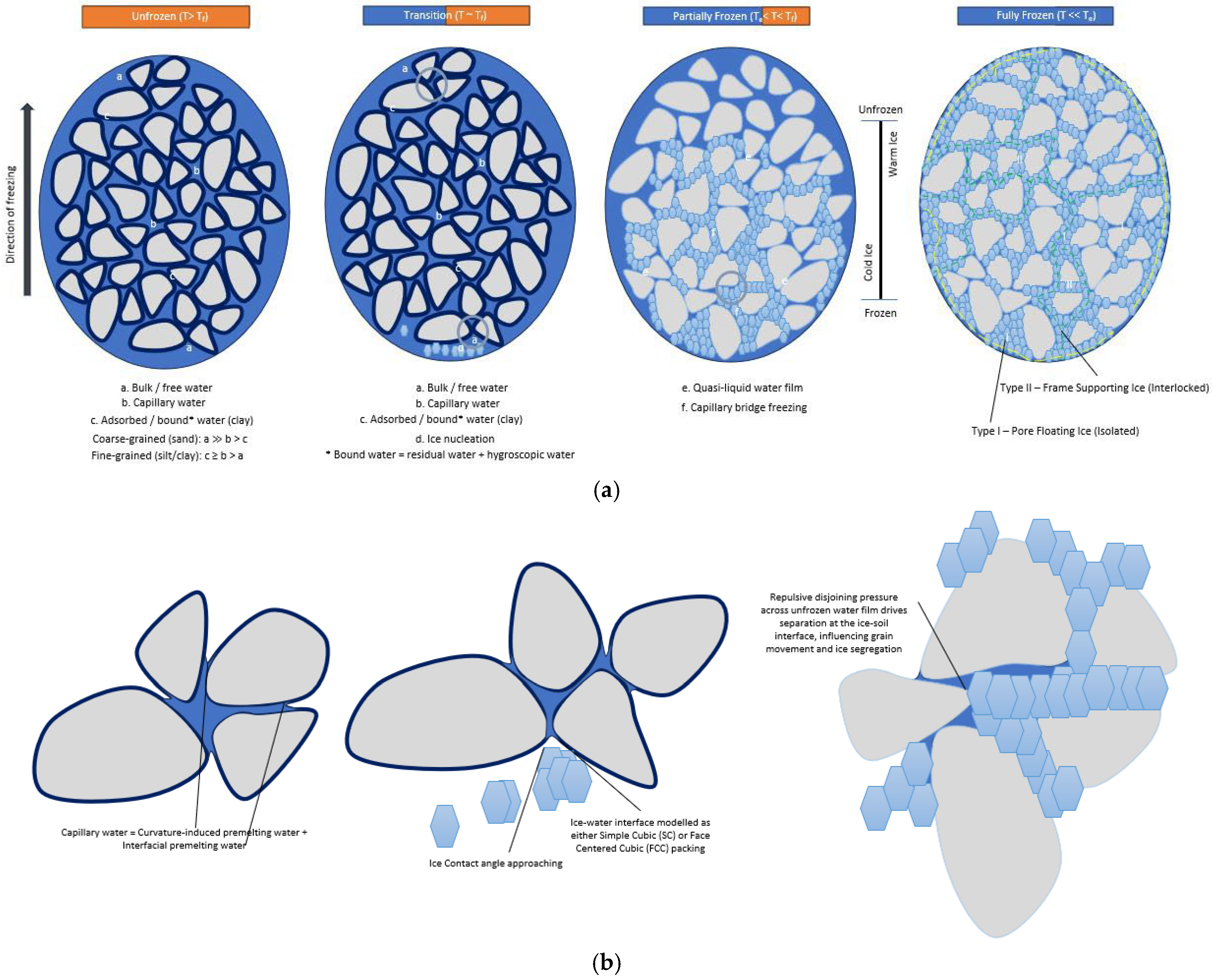

- unfrozen (T > Tf) —bulk/free water coexists with capillary and adsorbed/bound films, and no ice has yet formed;

- (ii)

- transition (T ~ Tf) —capillary and adsorbed water persist while heterogeneous ice nucleation initiates in the largest pores at around freezing temperature, Tf;

- (iii)

- partially frozen (Te < T < Tf) —quasi-liquid water films remain and capillary bridges progressively freeze as temperature drops from start Tf to the end Te of the freezing range [29];

- (iv)

- fully frozen (T << Te)—two ice configurations emerge: Type I (pore-floating, isolated) and Type II (interlocked, frame-supporting) at the end of freezing Te, consistent with micro-CT observations of isolated vs. load-bearing ice networks in frozen granular materials [38].

- (i)

- decomposition of capillary water into curvature-induced components and interfacial premelting water films;

- (ii)

- advance of ice-water interfaces constrained by soil particles and approaching contact angle equilibration;

- (iii)

- repulsive disjoining pressure across quasi-liquid films that influences ice–soil segregation and interface dynamics. The ice-water interface is modeled using simple-cubic) or face-centered cubic packings to illustrate pore-scale geometry in the partially frozen stage.

2.2. Soil Freezing Characteristic Curve

- (i)

- Stage I—metastable nucleation and bulk/free water plateau (Tsc < T< Tf*)—A short metastable interval may occur between the supercooled state and the onset of pore ice nucleation. Latent heat release raises the temperature toward Tf* and produces a brief plateau in UWC, pronounced in coarse-grained soils, negligible in fine-grained soils.

- (ii)

- Stage II—freezing of capillary water and increase in cryosuction (Tf* < T < Te)—With continued cooling below Tf*, capillary water freezes progressively across the pore size distribution. UWC decreases sharply while suction increases (cryosuction increases from a decrease in liquid pressure relative to ice pressure). Compared with coarse-grained soils (short range), Stage II in fine-grained soils spans a wider temperature interval and extends to a lower Te.

- (iii)

- Stage III—freezing of adsorbed/bound (T~Te)—Near the end of freezing, Te, the remaining adsorbed/bound water for fine-grained soil solidifies with little release of any additional latent heat effect. UWC asymptotically approaches the residual value of unfrozen water content, (θresidual). Beyond the end of freezing (T < Te), further cooling can occur without any phase change.

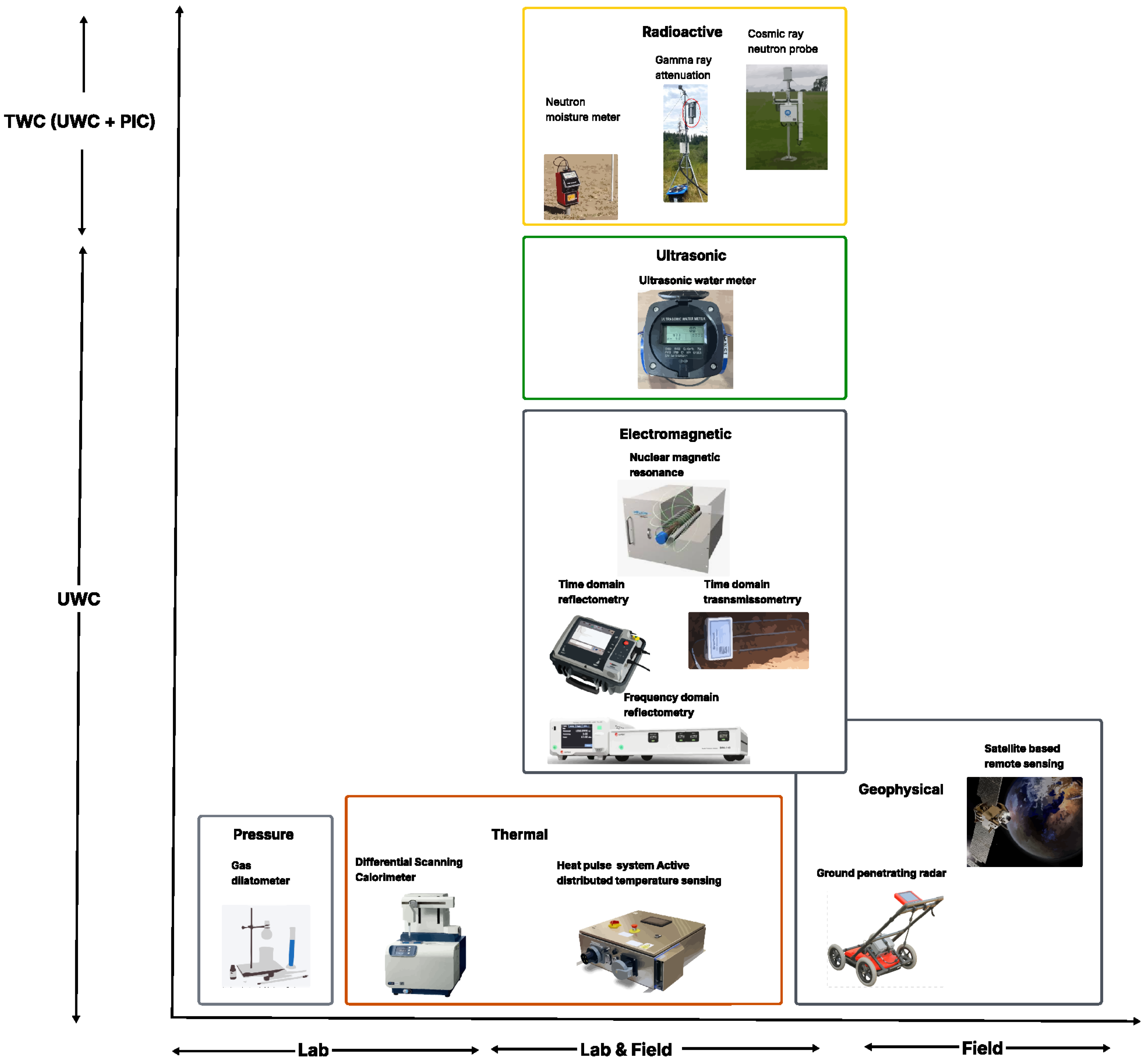

3. Measurement Techniques for UWC

3.1. Laboratory Techniques

3.1.1. Gravimetric Methods

3.1.2. Dilatometry (Volumetric and Pressure)

3.1.3. Differential Scanning Calorimetry

3.1.4. Laboratory Heat Pulse

3.1.5. Bench-Top Nuclear Magnetic Resonance

3.2. Lab and Field Techniques

3.2.1. Dielectric (Capacitance)

3.2.2. Time Domain Reflectometry and Transmissometry

3.2.3. Heat Pulse Probes

3.2.4. Neutron Moisture Meter

3.2.5. Gamma Ray Attenuation

3.2.6. Ultrasonic Sensors

3.3. Field Techniques

3.3.1. Cosmic Ray Neutron Probe

3.3.2. Borehole NMR

3.3.3. Ground Penetrating Radar

3.3.4. Remote Sensing

3.4. Integrated Multiscale Approach

| Method | Principle | Attributes | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gravimetric (Oven-drying) | Weighing soil before and after drying to compute total water; freeze/thaw separation can isolate unfrozen water. | Simple and accurate but destructive and not suitable for in situ use. | ASTM D2216; [40]; |

| Dilatometry (Volumetric) | Measuring pressure change in sealed saturated samples due to 9% volume expansion upon freezing of water to ice. | Not widely commercialized; requires paste-like preparation and complex lab-based setup. | [3,45,46] |

| Dielectric (Capacitance) | Measuring bulk permittivity via capacitance sensors; water has high dielectric contrasts with ice/soil. | Rapid, non-destructive, but needs calibration; affected by salinity, density, etc. | [59,60] |

| Time Domain Reflectometry (TDR) | Sending EM pulses along probes and measuring travel time (related to permittivity and thus water content). | Real-time monitoring in both lab and field and requires calibration; otherwise, it may overestimate UWC if some ice is interpreted as liquid without proper models. Response time ~ 0.5 min. | [54,61] |

| Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) | Based on relaxation times (e.g., T2) for hydrogen protons. Detecting hydrogen protons; different relaxation times for liquid water vs. ice-bound water. | Effective for distinguishing UWC vs. PIC; sensitive to temperature; highly accurate but expensive and often lab-based (sensitive to temperature control). | [23,62,63] |

| Neutron Scattering (NMM/CRNP) | Fast neutrons slowed by hydrogen in water; counting slowed neutrons to infer the moisture content. | Effective for field profiling applications at 10–70 cm depth and large-scale monitoring (cosmic-ray probes cover ~300 m radius); cannot directly distinguish ice vs. liquid and involves radioactive sources. | [57,64] |

| Calorimetry (DSC) | Measuring heat flow during controlled freezing/thawing (latent heat) to back-calculate phase change fractions. | Precise but slow determination of freezing/melting behavior in a lab with a response time ~ 35 min; requires known heat capacities, not an in-situ method. | [47,65] |

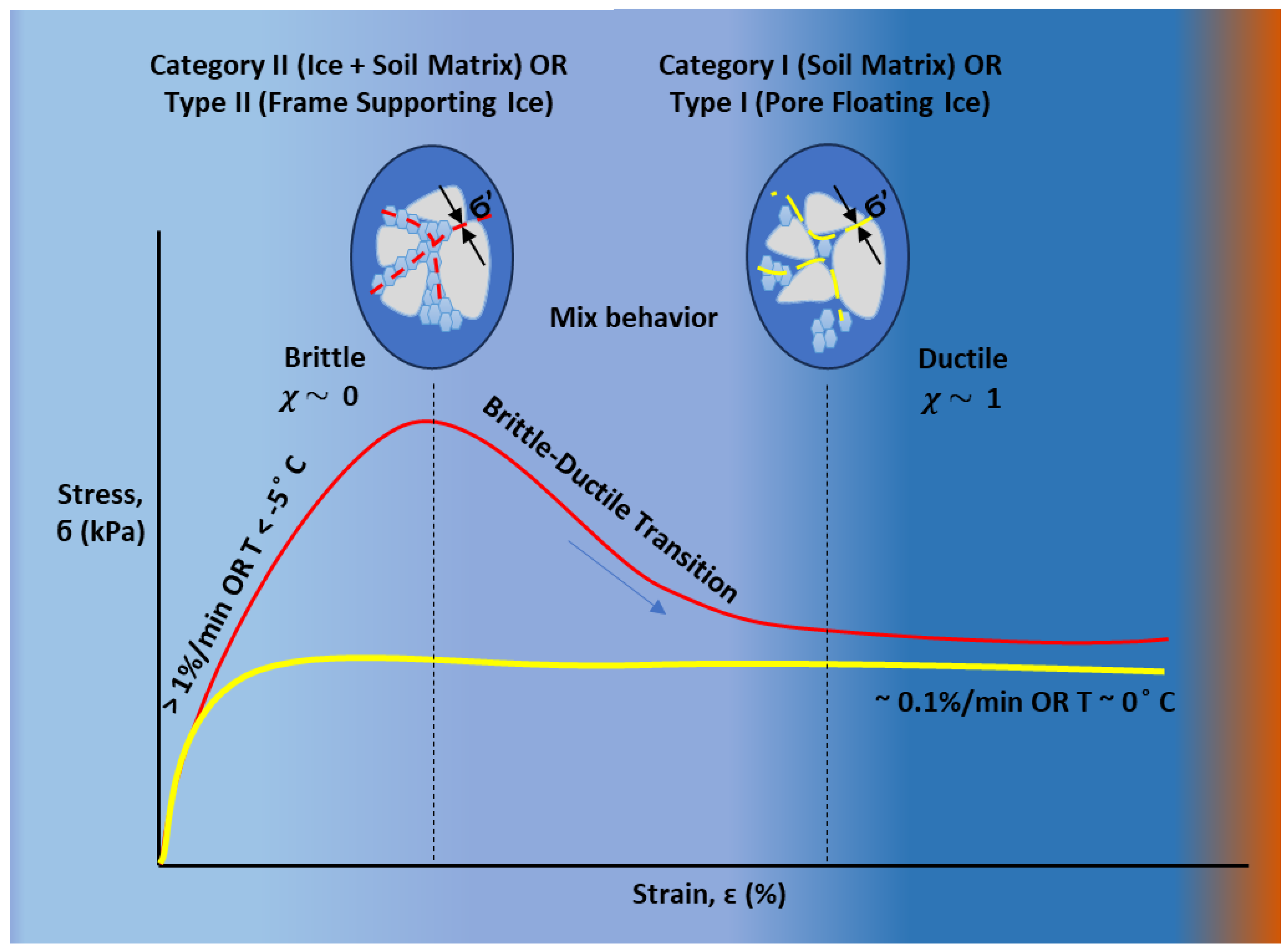

4. Mechanical Behavior and Effective Stress in PFS

4.1. Revised Effective Stress for PFS

- (i)

- Category I: only the soil skeleton bears effective stress, with water and ice both acting as pore fluids.

- (ii)

- Category II: both the soil skeleton and ice matrix are co-load-bearing, incorporating cryogenic suction and interparticle bonding

4.2. Ice Morphology and Load Transfer Mechanisms

- (i)

- Type I (pore floating ice) refers to isolated or disconnected ice that occupies pore spaces without forming a load-bearing structure, suitable for Category I formulations.

- (ii)

- Type II (frame supporting ice) develops as a connected network or ice lens that actively carries load and reinforces the soil, as modeled in Category II.

4.3. Cryogenic Suction and Pore Pressure Evolution

4.4. Rate- and Temperature-Dependent Mechanical Behavior

4.5. Strength Behavior During Freezing and Thawing

4.6. Constitutive Modeling Approach

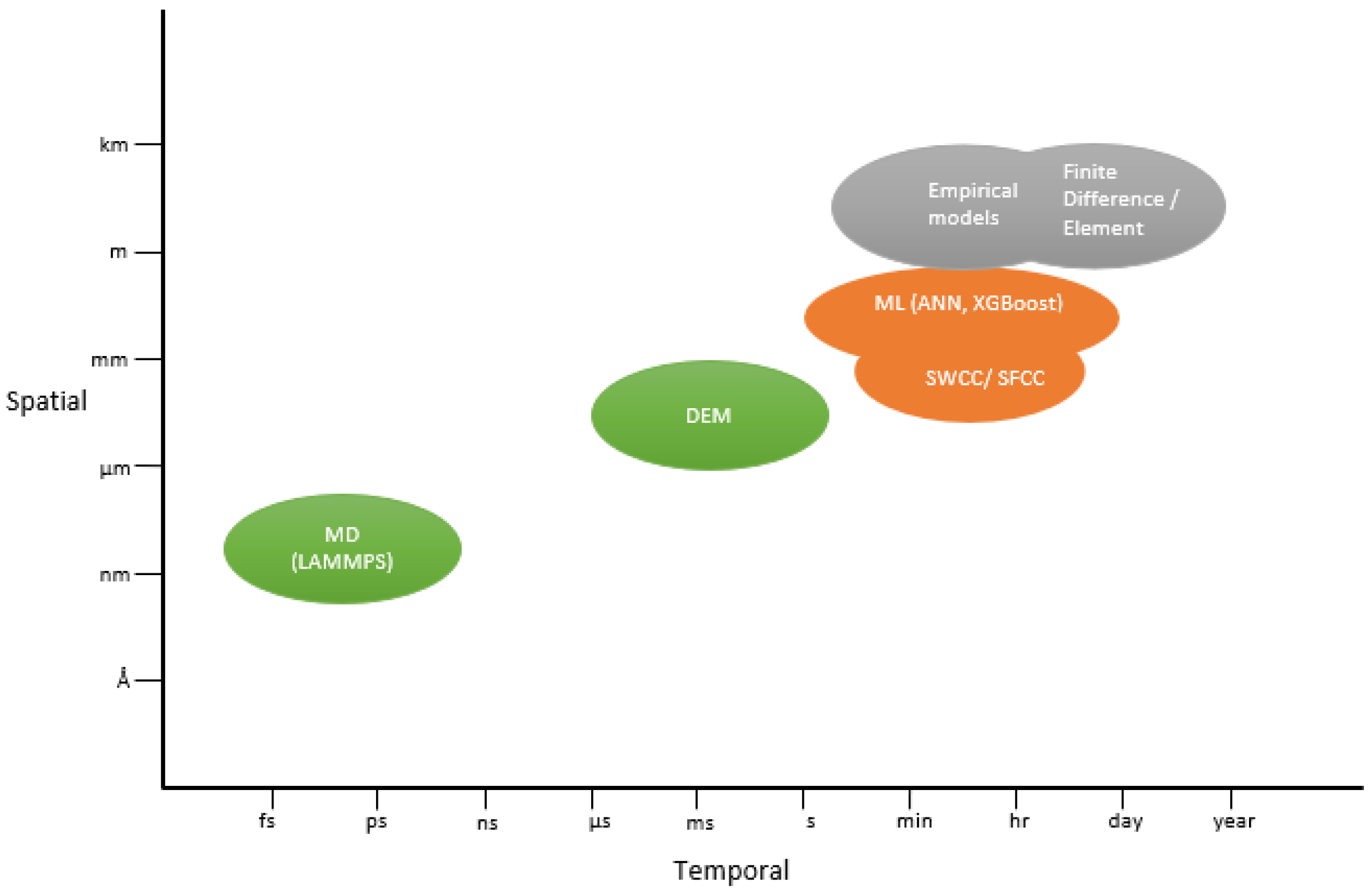

5. Modelling Approaches for UWC and PFS Behavior

5.1. Thermodynamic and Pore-Scale Theoretical Models

5.2. Empirical and Semi-Empirical SFCC/SWCC Formulations

5.3. Data-Driven and Machine Learning Methods

5.4. Molecular Dynamics Simulations

- (i)

- The mineral-dominated zone, where water molecules are tightly bound to mineral surfaces due to strong adsorption forces;

- (ii)

- The transition zone, where water molecules exhibit intermediate properties between tightly bound and freely mobile states;

- (iii)

- The ice-dominated zone, where water molecules form a quasi-liquid layer at the ice interface.

- (i)

- Quick freezing, where water in large pores solidifies rapidly, causing a sharp decline in UWC;

- (ii)

- The transitional stage, where capillary water gradually freezes, resulting in a slower decline in UWC;

- (iii)

- The stability stage, where there are minimal changes in UWC, with only bound water persisting at ultra-low temperatures.

5.5. Integrated Multiscale and Hybrid Modeling Framework

| Model Category | Approach (Phase–Temperature Relationship) | Limitation | Example Works (Reference Models) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Theoretical (physics-based) | Thermodynamic and interfacial energy formulations based on Gibbs–Thomson effect, pore size, and disjoining pressure. | Offer fundamental insight but involve simplifications | Premelting theory [30]; Disjoining pressure [120]; Cryogenic suction segregation [70] |

| Empirical/ Semi-empirical | Curve fitting experimental data with convenient equations, often using soil index properties to adjust curves. | Easy to apply, however, not universally transferable | Power-law SFCC [40]; SSA/clay-based UWC [95,96,97] |

| SWCC/ SFCC-based | Adapt unsaturated soil models (SWCC) to freezing conditions; use soil retention curve concepts with CCE to relate suction–temperature. | Require soil-specific calibration and may not capture hysteresis or ice morphology effects | Van Genuchten/SFCC [45,106]; Electrostatic effects [45,93,94,104] |

| Machine Learning (ML) | Train statistical or ML models on datasets of soil freezing behavior to predict UWC without explicit physical equations. | Can be meaningless with non-physical outputs | Neural network [109]; Gradient Boost [44]; Monotonic NN [110,111] |

| Molecular Dynamics and Simulation | Simulate behavior at the pore or atomic scale level for phase changes and interfacial water properties. | Highly detailed, however, computationally demanding | MD with LAMMPS [114,115,116,121]; GAN-based 3D soil structure [118,122] |

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bi, J.; Wang, G.; Wu, Z.; Wen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, G.; Sun, T. Investigation on Unfrozen Water Content Models of Freezing Soils. Front. Earth Sci. 2023, 10, 1039330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuvilin, E.M.; Bukhanov, B.A.; Mukhametdinova, A.Z.; Grechishcheva, E.S.; Sokolova, N.S.; Alekseev, A.G.; Istomin, V.A. Freezing Point and Unfrozen Water Contents of Permafrost Soils: Estimation by the Water Potential Method. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2022, 196, 103488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouyoucos, G.J. Measurement of the Inactive or Unfree Moisture in the Soil by Means of the Dilatometer Method. J. Agric. Res. 1917, 8, 195–217. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, P.J. Unfrozen Water Content of Frozen Soils and Soil Moisture Suction. Géotechnique 1964, 14, 231–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyalov, S.S. Methods of Determining Creep, Long-Term Strength and Compressibility Characteristics of Frozen Soils. Nrc Div Bldg Res Tech Transl/Can/. 1969. Available online: https://nrc-publications.canada.ca/eng/view/object/?id=14d51ca2-bade-40d0-a9e9-0bb7de42437b (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Ishizaki, T.; Maruyama, M.; Furukawa, Y.; Dash, J.G. Premelting of Ice in Porous Silica Glass. J. Cryst. Growth 1996, 163, 455–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D.M.; Tice, A.R. Low-Temperature Phases of Interfacial Water in Clay-Water Systems. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1971, 35, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsytovich, N.A. The Mechanics of Frozen Ground; Scripta Book Company: Frankfurt, Germany, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M.W.; Tice, A.R. Measurement of the Unfrozen Water Content of Soils: Comparison of NMR and TDR Methods; US Army Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory: Hanover, NH, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, S.; Chen, J.; Jones, S.B.; Flerchinger, G.; Dyck, M.; Filipovic, V.; Hu, Y.; Si, B.; Lv, J.; Wu, Q.; et al. Miscellaneous Methods for Determination of Unfrozen Water Content in Frozen Soils. J. Hydrol. 2024, 631, 130802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Zhang, H.; Lv, J.; Dyck, M.; Wu, Q.; He, H. A Scientometric Review of Research Status on Unfrozen Soil Water. Water 2021, 13, 708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.-Q.; Yin, Z.-Y.; Qi, J.-L.; Liu, Y. State-of-the-Art Constitutive Modelling of Frozen Soils. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2024, 31, 3801–3842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.-Q.; Yin, Z.-Y.; Yang, Z.-H.; Liu, Y. State of the Art of Mechanical Behaviors of Frozen Soils through Experimental Investigation. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2025, 236, 104497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.D. Frost Heaving in Non-Colloidal Soils. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Permafrost, Edmonton, AB, Canada, 10–13 July 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Black, P.B. Applications of the Clapeyron Equation to Water and Ice in Porous Media; US Army Corps of Engineers, Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory: Hanover, NH, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Henry, K.S. A Review of the Thermodynamics of Frost Heave; US Army Corps of Engineers: Hanover, NH, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Arenson, L.U.; Springman, S.M. Triaxial Constant Stress and Constant Strain Rate Tests on Ice-Rich Permafrost Samples. Can. Geotech. J. 2005, 42, 412–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, K.S.; Zhu, M.; Michalowski, R.L. Evaluation of Three Frost Heave Models. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on the Bearing Capacity of Roads, Railways and Airfields (BCRA’05), Trondheim, Norway, 25–27 June 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hoekstra, P. Moisture Movement in Soils under Temperature Gradients with the Cold-side Temperature below Freezing. Water Resour. Res. 1966, 2, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamberlain, E.; Groves, C.; Perham, R. The Mechanical Behaviour of Frozen Earth Materials under High Pressure Triaxial Test Conditions. Géotechnique 1972, 22, 469–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, J.G.; Rempel, A.W.; Wettlaufer, J.S. The Physics of Premelted Ice and Its Geophysical Consequences. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2006, 78, 695–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Dou, Z. Quantification and Division of Unfrozen Water Content during the Freezing Process and the Influence of Soil Properties by Low-Field Nuclear Magnetic Resonance. J. Hydrol. 2021, 602, 126719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Wei, C.; Lai, Y.; Chen, P. Quantification of Water Content during Freeze–Thaw Cycles: A Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Based Method. Vadose Zone J. 2018, 17, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, X.; Yang, Z. (Joey) Pore Water Freezing Characteristic in Saline Soils Based on Pore Size Distribution. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2020, 173, 103030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, E.; Wan, X.; Qu, M.; Zheng, L.; Zhong, C.; Gong, F.; Liu, L. Estimating Unfrozen Water Content in Frozen Soils Based on Soil Particle Distribution. J. Cold Reg. Eng. 2020, 34, 04020002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Xu, Y.; Lv, Y.; Nie, L.; Kong, F.; Yang, S.; Wang, H.; Li, T. Characterization of Unfrozen Water in Highly Organic Turfy Soil during Freeze–Thaw by Nuclear Magnetic Resonance. Eng. Geol. 2023, 312, 106937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, G.; Thornton, C.; Adams, M.J. A Theoretical Study of the Liquid Bridge Forces between Two Rigid Spherical Bodies. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1993, 161, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, X.; Zhu, J.; Pei, W.; Zhou, F.; Lu, J.; Yan, Z.; Wa, D. A Theoretical Model on Unfrozen Water Content in Soils and Verification. J. Hydrol. 2023, 622, 129675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, X.; Pei, W.; Lu, J.; Zhang, X.; Yan, Z.; Pirhadi, N. Prediction of the Unfrozen Water Content in Soils Based on Premelting Theory. J. Hydrol. 2022, 608, 127505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wettlaufer, J.S.; Worster, M.G. Premelting Dynamics. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 2006, 38, 427–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Niu, F.; Zheng, H.; Akagawa, S.; Lin, Z.; Luo, J. Experimental Measurement and Numerical Simulation of Frost Heave in Saturated Coarse-Grained Soil. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2017, 137, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Zhou, G.; Zhou, Y.; Vandeginste, V. Frost Heave in Freezing Soils: A Quasi-Static Model for Ice Lens Growth. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2019, 158, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilpin, R.R. A Model of the “Liquid-like” Layer between Ice and a Substrate with Applications to Wire Regelation and Particle Migration. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1979, 68, 235–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furukawa, Y.; Ishikawa, I. Direct Evidence for Melting Transition at Interface between Ice Crystal and Glass Substrate. J. Cryst. Growth 1993, 128, 1137–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Liu, X.; Chen, H.; Wang, X.; Guo, L.; Wang, X. Solid–Liquid Interface Disjoining Pressure of Frozen Clay and Its Effect on Water Transport. J. Cryst. Growth 2023, 614, 127218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Style, R.W.; Peppin, S.S.L.; Cocks, A.C.F.; Wettlaufer, J.S. Ice-Lens Formation and Geometrical Supercooling in Soils and Other Colloidal Materials. Phys. Rev. E 2011, 84, 041402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revil, A.; Leroy, P.; Titov, K. Characterization of Transport Properties of Argillaceous Sediments: Application to the Callovo-Oxfordian Argillite. J. Geophys. Res. 2005, 110, 2004JB003442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priest, J.A.; Rees, E.V.L.; Clayton, C.R.I. Influence of Gas Hydrate Morphology on the Seismic Velocities of Sands. J. Geophys. Res. 2009, 114, 2009JB006284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersland, O.B.; Ladanyi, B. Frozen Ground Engineering; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, D.M.; Tice, A.R. Predicting Unfrozen Water Contents in Frozen Soils from Surface Area Measurements. Highw. Res. Rec. 1972, 393, 12–18. [Google Scholar]

- Azmatch, T.F.; Sego, D.C.; Arenson, L.U.; Biggar, K.W. Using Soil Freezing Characteristic Curve to Estimate the Hydraulic Conductivity Function of Partially Frozen Soils. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2012, 83–84, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Cheng, H.; Chen, H.; Guo, L.; Fang, Y.; Wang, X. Theoretical Study on Freezing Separation Pressure of Clay Particles with Surface Charge Action. Crystals 2022, 12, 1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, M.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, H.; Mu, Y.; Sun, G.; Yin, Z. A Method for Calculating Unfrozen Water Content of Silty Clay with Consideration of Freezing Point. Appl. Clay Sci. 2018, 161, 474–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nartowska, E.; Sihag, P. Exploring Machine Learning Models to Predict the Unfrozen Water Content in Copper-Contaminated Clays. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2024, 227, 104296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaans, E.J.A.; Baker, J.M. The Soil Freezing Characteristic: Its Measurement and Similarity to the Soil Moisture Characteristic. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1996, 60, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pusch, R. Unfrozen Water as a Function of Clay Microstructure. Eng. Geol. 1979, 13, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horiguchi, K. Determination of Unfrozen Water Content by DSC. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Ground Freezing, Sapporo, Japan, 5–7 August 1985; pp. 33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.; Han, C.; Yu, X. (Bill) A Non-Destructive Method to Measure the Thermal Properties of Frozen Soils during Phase Transition. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2015, 7, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Dyck, M.F.; Horton, R.; Ren, T.; Bristow, K.L.; Lv, J.; Si, B. Development and Application of the Heat Pulse Method for Soil Physical Measurements. Rev. Geophys. 2018, 56, 567–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrov, O.V.; Furó, I. NMR Cryoporometry: Principles, Applications and Potential. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 2009, 54, 97–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Dyck, M. Application of Multiphase Dielectric Mixing Models for Understanding the Effective Dielectric Permittivity of Frozen Soils. Vadose Zone J. 2013, 12, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittelli, M.; Flury, M.; Roth, K. Use of Dielectric Spectroscopy to Estimate Ice Content in Frozen Porous Media. Water Resour. Res. 2004, 40, 2003WR002343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.J.; Young, G.D. A Cost Effective Soil Moisture Instrument Based on Time-Domain Transmission Measurement. In Proceedings of the International Symposium and Workshop on Time Domain Reflectometry for Innovative Geotechnical Applications, Evanston, IL, USA, 5–7 September 2001; pp. 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Blonquist, J.M., Jr.; Jones, S.B.; Robinson, D.A. A Time Domain Transmission Sensor with TDR Performance Characteristics. J. Hydrol. 2005, 314, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Dyck, M.; Wang, J.; Lv, J. Evaluation of TDR for Quantifying Heat-Pulse-Method-Induced Ice Melting in Frozen Soils. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2015, 79, 1275–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Aogu, K.; Li, M.; Xu, J.; Sheng, W.; Jones, S.B.; González-Teruel, J.D.; Robinson, D.A.; Horton, R.; Bristow, K.; et al. A Review of Time Domain Reflectometry (TDR) Applications in Porous Media. In Advances in Agronomy; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; Volume 168, pp. 83–155. ISBN 978-0-12-824589-7. [Google Scholar]

- Zreda, M.; Shuttleworth, W.J.; Zeng, X.; Zweck, C.; Desilets, D.; Franz, T.; Rosolem, R. COSMOS: The Cosmic-Ray Soil Moisture Observing System. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2012, 16, 4079–4099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowlandson, T.L.; Berg, A.A.; Roy, A.; Kim, E.; Pardo Lara, R.; Powers, J.; Lewis, K.; Houser, P.; McDonald, K.; Toose, P.; et al. Capturing Agricultural Soil Freeze/Thaw State through Remote Sensing and Ground Observations: A Soil Freeze/Thaw Validation Campaign. Remote Sens. Environ. 2018, 211, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topp, G.C.; Davis, J.L.; Annan, A.P. Electromagnetic Determination of Soil Water Content: Measurements in Coaxial Transmission Lines. Water Resour. Res. 1980, 16, 574–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, B.H.; Singh, D.N. Moisture Content Determination by TDR and Capacitance Techniques: A Comparative Study. Int. J. Earth Sci. Eng 2011, 4, 132–137. [Google Scholar]

- Giese, K.; Tiemann, R. Determination of the Complex Permittivity from Thin-Sample Time Domain Reflectometry Improved Analysis of the Step Response Waveform. Adv. Mol. Relax. Process. 1975, 7, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coates, G.R.; Xiao, L.; Prammer, M.G. NMR Logging: Principles and Applications; Halliburton Energy Services: Houston, TX, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kruse, A.M.; Darrow, M.M.; Akagawa, S. Improvements in Measuring Unfrozen Water in Frozen Soils Using the Pulsed Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Method. J. Cold Reg. Eng. 2018, 32, 04017016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franz, T.E.; Zreda, M.; Ferre, T.P.A.; Rosolem, R.; Zweck, C.; Stillman, S.; Zeng, X.; Shuttleworth, W.J. Measurement Depth of the Cosmic Ray Soil Moisture Probe Affected by Hydrogen from Various Sources. Water Resour. Res. 2012, 48, 2012WR011871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mironov, V.L.; Karavayskiy, A.Y.; Lukin, Y.I.; Pogoreltsev, E.I. Joint Studies of Water Phase Transitions in Na-Bentonite Clay by Calorimetric and Dielectric Methods. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2018, 153, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Chen, F.; Su, B.; Cheng, G. Theoretical Frame of the Saturated Freezing Soil. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2002, 35, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Cui, W.; Wang, D. Applicability of the Principle of Effective Stress in Cold Regions Geotechnical Engineering. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2024, 219, 104129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, H.R.; Cleall, P.; Li, Y.-C.; Harris, C.; Kern-Luetschg, M. Modelling of Cryogenic Processes in Permafrost and Seasonally Frozen Soils. Géotechnique 2009, 59, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Chen, F.; Xu, B.; Swoboda, G. Theoretical Modeling Framework for an Unsaturated Freezing Soil. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2008, 54, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, K.; Miller, R.D. Exploration of a Rigid Ice Model of Frost Heave. Water Resour. Res. 1985, 21, 281–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nixon, J.F. (Derick) Discrete Ice Lens Theory for Frost Heave in Soils. Can. Geotech. J. 1991, 28, 843–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackay, J.R. The Origin of Hummocks, Western Arctic Coast, Canada. Can. J. Earth Sci. 1980, 17, 996–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konrad, J.-M.; Morgenstern, N.R. A Mechanistic Theory of Ice Lens Formation in Fine-Grained Soils. Can. Geotech. J. 1980, 17, 473–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, T. Lateral Deformation of Freezing Clay under Triaxial Stress Condition Using Laser-Measuring Device. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2002, 35, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenson, L.U.; Johansen, M.M.; Springman, S.M. Effects of Volumetric Ice Content and Strain Rate on Shear Strength under Triaxial Conditions for Frozen Soil Samples. Permafr. Periglac. 2004, 15, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Wang, Y.; Yin, Z.; Zhang, H. Effect of Temperature and Strain Rate on Mechanical Characteristics and Constitutive Model of Frozen Helin Loess. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2017, 136, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, Y.; Springman, S.M. Axial Compression Stress Path Tests on Artificial Frozen Soil Samples in a Triaxial Device at Temperatures Just below 0 °C. Can. Geotech. J. 2014, 51, 1178–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Jiang, H.; Wang, E.; Liu, X.; Du, S. Variation and Prediction of Unfrozen Water Content in Different Soils at Extremely Low Temperature Conditions. J. Hydrol. 2023, 624, 129900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Beier, N.A.; Sego, D.C. Strength of Partially Frozen Sand under Triaxial Compression. Can. Geotech. J. 2023, 60, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goughnour, R.R.; Andersland, O.B. Mechanical Properties of a Sand-Ice System. J. Soil Mech. Found. Div. 1968, 94, 923–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting, J.M.; Torrence Martin, R.; Ladd, C.C. Mechanisms of Strength for Frozen Sand. J. Geotech. Eng. 1983, 109, 1286–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, L.; Matsushima, J. Rock-Physics Modeling of Ultrasonic P- and S-Wave Attenuation in Partially Frozen Brine and Unconsolidated Sand Systems and Comparison with Laboratory Measurements. Geophysics 2019, 84, MR153–MR171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Wang, S.; Yu, F. A Review on Creep of Frozen Soils. In Constitutive Modeling of Geomaterials; Yang, Q., Zhang, J.-M., Zheng, H., Yao, Y., Eds.; Springer Series in Geomechanics and Geoengineering; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 129–133. ISBN 978-3-642-32813-8. [Google Scholar]

- Shibata, T. Time-Dependence and Volumetric Change Characteristic of Frozen Sand under Triaxial Stress Condition. In Proceedings of the 4th International Symposium on Ground Freezing, Sapporo, Japan, 5–7 August 1985; Volume 1, pp. 173–179. [Google Scholar]

- Li, N.; Chen, B.; Chen, F.; Xu, X. The Coupled Heat-Moisture-Mechanic Model of the Frozen Soil. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2000, 31, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladanyi, B.; Morel, J.-F. Effect of Internal Confinement on Compression Strength of Frozen Sand. Can. Geotech. J. 1990, 27, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konrad, J.; Duquennoi, C. A Model for Water Transport and Ice Lensing in Freezing Soils. Water Resour. Res. 1993, 29, 3109–3124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; Zhu, C. THM Model of Saturated Partially Frozen Soils: From Pore-Scale Ice Morphology to Macroscopic Behaviors. In Proceedings of the Geo-Congress 2024, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 25–28 February 2024; American Society of Civil Engineers: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2024; pp. 769–779. [Google Scholar]

- Amini, D.; Maghoul, P.; Holländer, H.; Bilodeau, J.-P. A Critical State-Based Thermo-Elasto-Viscoplastic Constitutive Model for Thermal Creep Deformation of Frozen Soils. Acta Geotech. 2024, 19, 2955–2973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopmans, R.W.R.; Miller, R.D. Soil Freezing and Soil Water Characteristic Curves. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1966, 30, 680–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, K.; Mizoguchi, M. Amount of Unfrozen Water in Frozen Porous Media Saturated with Solution. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2002, 34, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rempel, A.W.; Wettlaufer, J.S.; Worster, M.G. Premelting Dynamics in a Continuum Model of Frost Heave. J. Fluid Mech. 2004, 498, 227–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Yang, W.; Gao, X.; Zhao, J.; Li, Z.; Jiang, J. Modeling the Unfrozen Water Content of Frozen Soil Based on the Absorption Effects of Clay Surfaces. Water Resour. Res. 2020, 56, e2020WR027482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Brouchkov, A.V.; Hu, J. Numerical Study of Pore Water Pressure in Frozen Soils during Moisture Migration. Water 2024, 16, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlowski, T. A Semi-Empirical Model for Phase Composition of Water in Clay–Water Systems. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2007, 49, 226–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Yu, X. Predicting the Phase Composition Curve in Frozen Soils Using Index Properties: A Physico-Empirical Approach. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2014, 108, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Wang, Y.; Sun, W.; Qi, J. Influence of Plasticity on Unfrozen Water Content of Frozen Soils as Determined by Nuclear Magnetic Resonance. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2020, 172, 102993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tice, A.R.; Oliphant, J.L.; Nakano, Y.; Jenkins, T.F. Relationship between the Ice and Unfrozen Water Phases in Frozen Soil as Determined by Pulsed Nuclear Magnetic Resonance and Physical Desorption Data. 1982. Available online: https://usace.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p266001coll1/id/7139 (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Mitchell, J.; Webber, J.; Strange, J. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Cryoporometry. Phys. Rep. 2008, 461, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, X.; Tan, D.; Lai, Y.; Li, S.; Lu, J.; Yan, Z. Experimental Study on Pore Water Phase Transition in Saline Soils. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2022, 203, 103661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, S.; Gens, A.; Olivella, S.; Jardine, R.J. THM-Coupled Finite Element Analysis of Frozen Soil: Formulation and Application. Géotechnique 2009, 59, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Michalowski, R.L. Thermal-Hydro-Mechanical Analysis of Frost Heave and Thaw Settlement. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2015, 141, 04015027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredlund, D.G.; Xing, A. Equations for the Soil-Water Characteristic Curve. Can. Geotech. J. 1994, 31, 521–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhou, J.; Shi, X.; Zhou, G. Practical Models Describing Hysteresis Behavior of Unfrozen Water in Frozen Soil Based on Similarity Analysis. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2019, 157, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheshukov, A.Y.; Nieber, J.L. One-dimensional Freezing of Nonheaving Unsaturated Soils: Model Formulation and Similarity Solution. Water Resour. Res. 2011, 47, 2011WR010512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Vanapalli, S.K.; Han, Z. Soil Freezing Process and Different Expressions for the Soil-Freezing Characteristic Curve. Sci. Cold Arid. Reg. 2017, 9, 221–228. [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, K.; Muto, Y.; Mizoguchi, M. Water and Solute Distributions near an Ice Lens in a Glass-Powder Medium Saturated with Sodium Chloride Solution under Unidirectional Freezing. Cryst. Growth Des. 2001, 1, 207–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, J.; Zhong, Y.; Zhang, S.; Sheng, D. A Mathematic Model for the Soil Freezing Characteristic Curve: The Roles of Adsorption and Capillarity. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2021, 181, 103178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Luo, Q.; Liu, J.; Wang, T.; Wang, L. Modeling of Frozen Soil-Structure Interface Shear Behavior by Supervised Deep Learning. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2022, 200, 103589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ren, J.; Fan, X.; Zhou, P.; Pu, Y.; Zhang, F. Estimation of Unfrozen Water Content in Frozen Soils Based on Data Interpolation and Constrained Monotonic Neural Network. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2024, 218, 104094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhou, P.; Pu, Y.; Ren, J.; Zhang, F.; Wang, C. Comparative Analysis of Machine Learning Techniques for Accurate Prediction of Unfrozen Water Content in Frozen Soils. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2024, 227, 104304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cygan, R.T.; Liang, J.-J.; Kalinichev, A.G. Molecular Models of Hydroxide, Oxyhydroxide, and Clay Phases and the Development of a General Force Field. J. Phys. Chem. B 2004, 108, 1255–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abascal, J.L.F.; Vega, C. A General Purpose Model for the Condensed Phases of Water: TIP4P/2005. J. Chem. Phys. 2005, 123, 234505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Pei, H. Determining the Bound Water Content of Montmorillonite from Molecular Simulations. Eng. Geol. 2021, 294, 106353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, P.; Zheng, Y.-Y.; Zaoui, A.; Ma, W.; Ren, Z. Ice-Unfrozen Water on Montmorillonite Surface: A Molecular Dynamics Study. Geomech. Energy Environ. 2024, 39, 100569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Hu, L. Molecular Insights into the Freezing Process of Water on the Basal Surface of Muscovite Mica. Appl. Clay Sci. 2024, 256, 107431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickory, R.W.; Eastwood, J.W. Computer Simulation Using Particles; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Argilaga, A.; Zhao, C.; Li, H.; Lei, L. Synthesising Microstructures of a Partially Frozen Salty Sand Using Voxel-Based 3D Generative Adversarial Networks. Comput. Geotech. 2024, 170, 106247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.-Q. Investigation of Soil-Soil and Soil-FRP Interfacial Mechanical Behavior Using Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Ph.D. Thesis, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Rempel, A.W. Microscopic and Environmental Controls on the Spacing and Thickness of Segregated Ice Lenses. Quat. Res. 2011, 75, 316–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Li, B.; Liu, J.; Wei, P.; Yao, Z. Characterization and Quantitative Analysis of Unfrozen Water at Ultra-Low Temperatures: Insights from NMR and MD Study. J. Hydrol. 2025, 647, 132354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahin, G.; Desrues, J.; Pont, S.D.; Combe, G.; Argilaga, A. A Study of the Influence of REV Variability in Double-scale FEM ×DEM Analysis. Int. J. Numer. Methods Eng. 2016, 107, 882–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, M.A. Mechanical Properties of Simulated Deep Permafrost. J. Eng. Ind. 1975, 97, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannell, G.H.; Gardner, W.H. Freezing-Point Depressions in Stabilized Soil Aggregates, Synthetic Soil, and Quartz Sand. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1959, 23, 418–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, J.G.; Fu, H.; Wettlaufer, J.S. The Premelting of Ice and Its Environmental Consequences. Rep. Prog. Phys. 1995, 58, 115–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen-Goos, H.; Wettlaufer, J.S. Theory of Ice Premelting in Porous Media. Phys. Rev. E 2010, 81, 031604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilpin, R.R. A Model for the Prediction of Ice Lensing and Frost Heave in Soils. Water Resour. Res. 1980, 16, 918–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stähli, M.; Stadler, D. Measurement of Water and Solute Dynamics in Freezing Soil Columns with Time Domain Reflectometry. J. Hydrol. 1997, 195, 352–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Wang, K.; Jin, L.; Yang, G.; Jia, H.; Taoum, A. A Resistivity Model for Testing Unfrozen Water Content of Frozen Soil. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2018, 153, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Waseem, M.O.; Sego, D.; Deng, L.; Beier, N. Pore Ice Content and Unfrozen Water Content Coexistence in Partially Frozen Soils: A State-of-the-Art Review of Mechanisms, Measurement Technology and Modeling Methods. Geotechnics 2025, 5, 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/geotechnics5040080

Waseem MO, Sego D, Deng L, Beier N. Pore Ice Content and Unfrozen Water Content Coexistence in Partially Frozen Soils: A State-of-the-Art Review of Mechanisms, Measurement Technology and Modeling Methods. Geotechnics. 2025; 5(4):80. https://doi.org/10.3390/geotechnics5040080

Chicago/Turabian StyleWaseem, Mohammad Ossama, Dave Sego, Lijun Deng, and Nicholas Beier. 2025. "Pore Ice Content and Unfrozen Water Content Coexistence in Partially Frozen Soils: A State-of-the-Art Review of Mechanisms, Measurement Technology and Modeling Methods" Geotechnics 5, no. 4: 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/geotechnics5040080

APA StyleWaseem, M. O., Sego, D., Deng, L., & Beier, N. (2025). Pore Ice Content and Unfrozen Water Content Coexistence in Partially Frozen Soils: A State-of-the-Art Review of Mechanisms, Measurement Technology and Modeling Methods. Geotechnics, 5(4), 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/geotechnics5040080