1. Introduction

The ability to produce high power output is a critical performance characteristic central to success in most sporting events, especially in activities that rely on jumping, change of direction, acceleration, and sprinting performance [

1,

2]. However, athletes are often required to produce several repetitions at or near maximal effort with brief rest periods over extended periods during the course of a competition. Repeat power ability (RPA) is the ability to repetitively produce peak power (PP) or near peak power (PP) during a high-volume set or across several high-volume sets [

3], which differs from muscular endurance that involves a relatively low level of force or power sustained during high numbers of repetitions. With the recent recognition that RPA is a key determinant of athletic performance, interest in designing resistance training programs to target improvement in RPA has risen. Yet the optimal exercise prescription to improve RPA remains unclear and requires further investigation.

When the objective is to produce PP, the given load must be moved at maximum possible velocity. A currently accepted training principle for improved PP is the use of a low volume with relatively long rest periods to minimize fatigue and maintain PP within 5–10% during each repetition [

4]. Less is known about training RPA with resistance exercises. While fatigue must arguably occur in training for adaptations to occur, it is reasonable to suggest that extensive fatigue should be avoided when the goal is to repetitively produce power at or near maximum. A recent meta-analysis study by Hernandez-Belmonte et al. [

5] reported that training with velocity loss thresholds less than 25%, setting limitations on the degree of fatigue, is better for strength, sprint, and jump improvement compared to higher levels of fatigue.

Rest between sets is a factor that must be considered when training to improve RPA. Hester et al. [

6] found no change in mean power across five sets of 16 repetitions with two minutes of rest using 40% 1RM on the squat, while PP decreased 18–22% within each set. In a similar design, Smilios et al. [

7] found reduced mean power and PP at set three during four sets of 20 with two minutes of rest in recreationally trained males. The subjects were provided assistance to complete all repetitions when needed and the load was reduced 10% each set when all repetitions could not be completed in the previous set, limiting the ability to determine the effect of rest between sets. In addition, a comparison of different rest periods between sets for RPA during high-volume repetitions and sets has yet to be carried out.

The majority of studies analyzing RPA have been conducted on male subjects [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13], with limited studies on females [

14]. Several studies have compared fatigue between the sexes during lower-body resistance exercise with mixed findings. Mackey et al. [

15] compared the effect of a squat-fatigue protocol on the time-course of recovery during a knee extension exercise and found no difference between males and females. However, Clark et al. [

16] found greater fatigue in maximum force output in males and speculated that the result was due to the production of greater absolute force, which created greater blood flow and oxygen occlusion. In support of this study, a review by Amdi et al. [

17] found little difference in fatigability between males and females but noted that males who produce greater absolute forces may show more fatigue when free-weight exercises are completed with minimal rest periods. However, no differences in fatigue, assessed with peak force, were found between the sexes when relatively low-volume-resistance protocols were completed [

18]. Currently, a direct comparison of 1 min vs. 2 min rest during a high-volume resistance protocol for RPA between males and females within and across sets requires further investigation.

In addition, the effect of training parameters on power output within a session is not well understood, with only two studies [

12,

14] previously establishing PP during a set to determine the level of decline within and across sets. Further, the effect of different rest periods during a high-volume resistance exercise session on RPA remains unclear. Thus, the purpose of this study was to determine RPA within and across sets of squats with one- and two-minute rest periods in resistance-trained males and females. We hypothesized that power output would decrease earlier within and across sets during the one-minute rest period and that males would demonstrate greater fatigue.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Twenty-five resistance-trained males (n = 13) and females (n = 12) between the ages of 18 and 47 completed the study. Participant inclusion criteria were the following: (1) age between 18 and 50 years, (2) minimum of one year of resistance training using free weights, (3) currently not taking any ergogenic supplements, (4) able to perform resistance exercise and testing without any physical limitations, and (5) no caffeine or stimulant consumption on testing day. Mean training experience was 4.5 yrs that varied from a focus on muscular endurance, hypertrophy, and strength to Olympic lifting. While absolute strength was significantly greater in males (144.6 vs. 95.5 kg; p < 0.001), relative strength between males (1.67) and females (1.49) was not significantly different (p = 0.12). Criteria for exclusion included any previous lower-limb injury within the past 6 months or neuromuscular conditions that would have prevented maximum effort and successful execution during high-volume squats. Completion of the study was on a volunteer basis.

2.2. Baseline Measurements

Participants reported to the Human Performance Laboratory on three separate visits. During session one, the participants completed an informed consent document as approved by the university’s Institutional Review Board for human participants. Age, height, and weight were recorded prior to a 10 min general and dynamic warm-up in preparation for the 1RM test on the barbell, back squat.

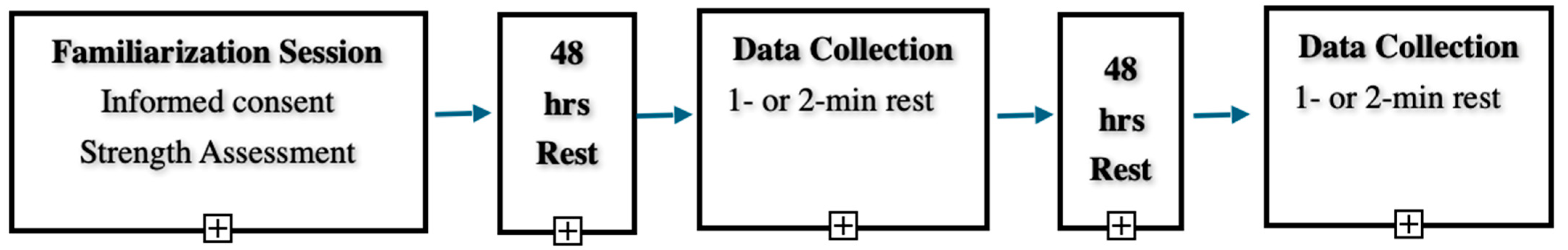

Figure 1 shows the research design.

2.3. RM Strength Testing

The warm-up sets consisted of 10 repetitions at approximately 50% of the subjects’ estimated 1RM load followed by two repetitions at approximately 70% and 80%, with a three-minute rest between sets. The 1RM attempts were performed following NSCA guidelines for maximum strength testing [

19]. Participants performed the 1RM test for the back squat on a Power Lift

® (Jefferson, IA, USA) multipurpose, adjustable half-rack system. The lift was performed with a 20 kg Olympic barbell. Each participant performed 5 air squats to determine the necessary parallel squat depth. An elastic band was positioned across the rack, designating the bar height associated with the parallel depth when in contact with the hamstrings [

6]. The participants were instructed to position the feet shoulder-width apart while maintaining an upright torso. Lastly, participants were instructed and monitored to ensure that the eccentric phase was completed at an approximate two-second rate to a parallel position followed by a concentric phase at maximum effort and velocity while maintaining flat feet [

10]. After determination of the 1RM, participants were then familiarized with the data collection squat protocol.

2.4. Data Collection Sessions

A minimum of 48 h of recovery was required prior to data collection sessions. The power measurements for the back-squat protocol were obtained using a Tendo Weightlifting Analyzer® (Tendo Power Analyzer V 314, Tendo Sports Machines; Trencin, Slovak Republic). Before data collection, participants completed a 5-min warm-up on a cycle and dynamic stretches followed by warm-up sets on the squat. The squat warm-up consisted of three sets of five repetitions, the 1st set at 30% 1RM and the 2nd and 3rd sets at 50% for three repetitions followed by five minutes of rest. Five sets were completed at an intensity of 45% 1RM. The set was terminated when power dropped below 80% of PP for two consecutive repetitions, incorrect form was unable to be completed, or volitional exhaustion occurred. The 20% loss in PP within the set was displayed by the measurement device and monitored in real time. Incorrect form was defined as the participant being unable to reach the proper depth for a parallel squat or excessive trunk flexion being determined. Lastly, the administrator gave verbal encouragement to perform the concentric phase with maximum velocity during the set. The protocol comprised one- and two-minute rests between sets completed in separate sessions in random order, with a minimum of 48 h of recovery.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Research has demonstrated high validity and test–retest reliability (intra-class correlation coefficient ranging from 0.85 to 0.98) using the instrumentation to assess power output during a full back-squat exercise, which was similar to the current data across the five sets (0.91–0.98) [

20]. In this study, the Chronbach Alpha test–retest reliability for each set was high in most cases. For the 1-min recovery time, the reliability coefficients for Set 1 (0.98), Set 2 (0.97), Set 3 (0.98), Set 4 (0.94), Set 5 (0.94), Set 6 (0.93), and Set 7 (0.91) were very high. The reliability coefficient for Set 8 was only 0.81, which is usually considered adequate. For the 2-min recovery time, the reliability coefficients for Set 1 (0.96), Set 2 (0.98), Set 3 (0.96), Set 4 (0.93), Set 5 (0.91), Set 6 (0.91), and Set 7 (0.90) were also very high; however, the reliability coefficient for Set 8 was only 0.76, which is less than adequate for data analysis.

Bartlett’s test was used to determine whether the basic assumption of equal variances was satisfied for conducting the ANOVA. For both the 1-min recovery time, c2(4) = 1.17, p = 0.88), and the 2-min recovery time, c2(4) = 1.06, p = 0.90), no significant differences in variance were observed among the sets,

To test for the basic assumption of normality for each set, the Shapiro–Wilk test was conducted for each set across both recovery times. For the 1-min recovery time, Set 1 (p = 0.50), Set 2 (p = 0.08), Set 3 (p = 0.27), Set 4 (p = 0.18), Set 5 (p = 0.08), and Set 8 (p = 0.12) were not significantly different from normal; however, Set 6 (p = 0.02) and Set 7 (p = 0.03) did not meet the assumption of normality. Similarly, for the 2-min recovery time, Set 1 (p = 0.06), Set 2 (p = 0.06), Set 3 (p = 0.10), Set 4 (p = 0.09), Set 5 (p = 0.20), and Set 8 (p = 0.19) were not significantly different from normal. However, Set 6 (p = 0.01) and Set 7 (p = 0.04) again did not meet the assumption of normality. Failure to meet the assumption of normality precludes the use of any ANOVA.

For full disclosure, each subject completed eight sets during each exercise test. However, following the tests for reliability and the basic assumption of normality, Sets 6–8 were excluded from the analyses. The distribution of PP values for Sets 6 and 7 were significantly different from normal for both recovery times, in violation of one of the basic assumptions of ANOVA. Set 8 lacked sufficient reliability for the 2-min recovery time and had barely adequate reliability for the 1-min recovery time. Also, including Set 8 in the analysis would be rather meaningless without the two preceding sets (Sets 6 and 7). Consequently, all subsequent analyses were conducted with the inclusion of only Sets 1 through 5.

A three-way ANOVA with repeated measures was used to determine differences in mean power across the two recovery times (a within-subjects factor), the five sets within each recovery time (a within-subjects factor), and sex (a between-subjects factor). Interactions among these three variables were also tested. Greenhouse–Geisser epsilon was used to adjust probability values for any variation in sphericity for power scores across sets. Partial η

2 was used to determine the effect size for each statistical test, based on the recommendation of Bakeman [

21] for repeated-measures ANOVA. Partial η

2 values lower than 0.05 represent small effects, values between 0.06 and 0.13 represent moderate effects, and values of 0.14 or greater represent large effects. According to Bakeman [

21], the size of the statistical effect is a good indication of the mean differences between the groups or trials being compared. Paired t-tests were used as post hoc comparisons across sets and repetitions, with an overall alpha level set at

p < 0.05. Bonferroni correction was applied for up to four planned comparisons for the PP within each set. The first comparison was between the repetition at 10% reduction from PP and the following repetition in order to keep the number of comparisons and the adjusted alpha level at a practical number. Three more comparisons were made to determine the significance of within-set fatigue if needed. The adjusted alpha level for these tests was 0.05/4 = 0.0125.

3. Results

The descriptive characteristics of the sample are reported in

Table 1 and

Table 2. These values include means, standard deviations, standard errors, and 95% confidence intervals for each mean.

Table 2 reports these same descriptive statistics with the sample divided between males and females. The descriptive statistics for power outputs during each recovery time and set are reported in

Table 3 and

Table 4.

Table 5 shows the number of repetitions completed in each set.

Table 6 reveals within-set results. A significant loss in PP within sets occurred between repetitions 9 and 11 during the one-minute recovery compared to 11–14 during the two-minute recovery.

Table S1 (Supplementary Table) provides power outputs across all repetitions during sets 1-5 for the one- and two-minute rest periods.

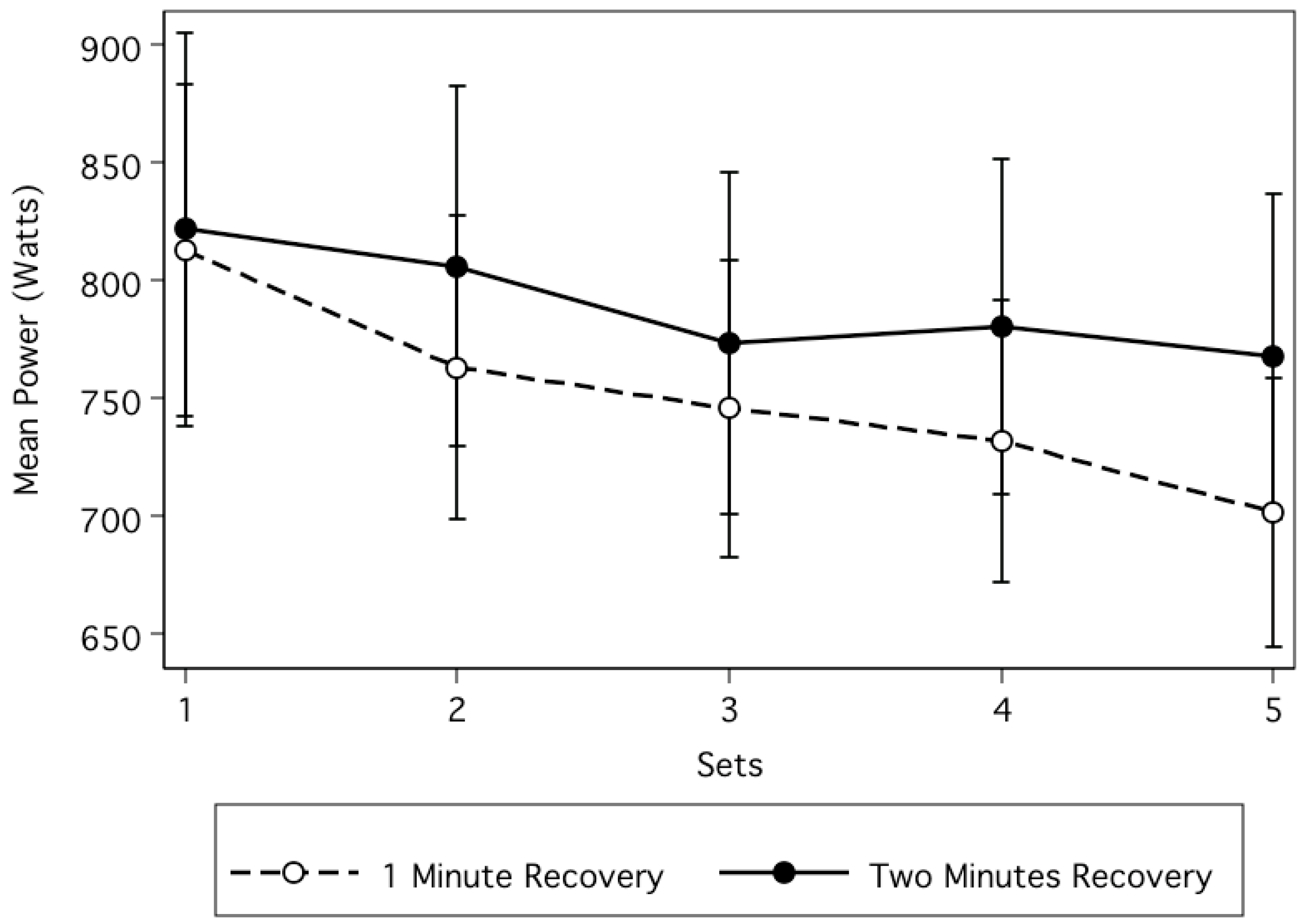

Repeated-measures ANOVA indicated a significant recovery time-by-set interaction—F(4, 92) = 4.1, Greenhouse–Geisser epsilon = 0.62, p = 0.015, partial η2 = 0.15—a large effect. Further, the analysis indicated a significant sex-by-set interaction—F(4, 92) = 8.7, Greenhouse–Geisser epsilon = 0.37, p = 0.002, partial η2= 0.27—a large effect. Also, a significant effect for sex was observed—F(1, 23) = 6.7, p = 0.017, partial η2 = 0.23—a large effect, with males recording greater mean power across both recovery times and sets. Lastly, there was no significant three-way interaction between recovery time, sets, and sex—F(4, 92) = 2.9, Greenhouse–Geisser epsilon = 0.62, p = 0.053, partial η2 = 0.11—a moderate effect.

The significant interaction between recovery time and sets indicates that the difference in PP among the sets is not the same for the one-minute and two-minute recovery times (

Figure 2). From the means reported in

Table 3, for the one-minute recovery time, it appears that fatigue caused a significant difference from a high of 812.8 watts in Set 1 to a low of 701.5 watts in Set 5, a difference of 111.3 watts, t(24) = 3.99,

p = 0.001. For the two-minute recovery time, there was a much smaller, and non-significant difference from a high of 821.8 watts in Set 1 to a low of 767.8 watts in Set 5, a difference of only 54.0 watts, t(24) = 2.21,

p = 0.019 (greater than the adjusted alpha of 0.0125).

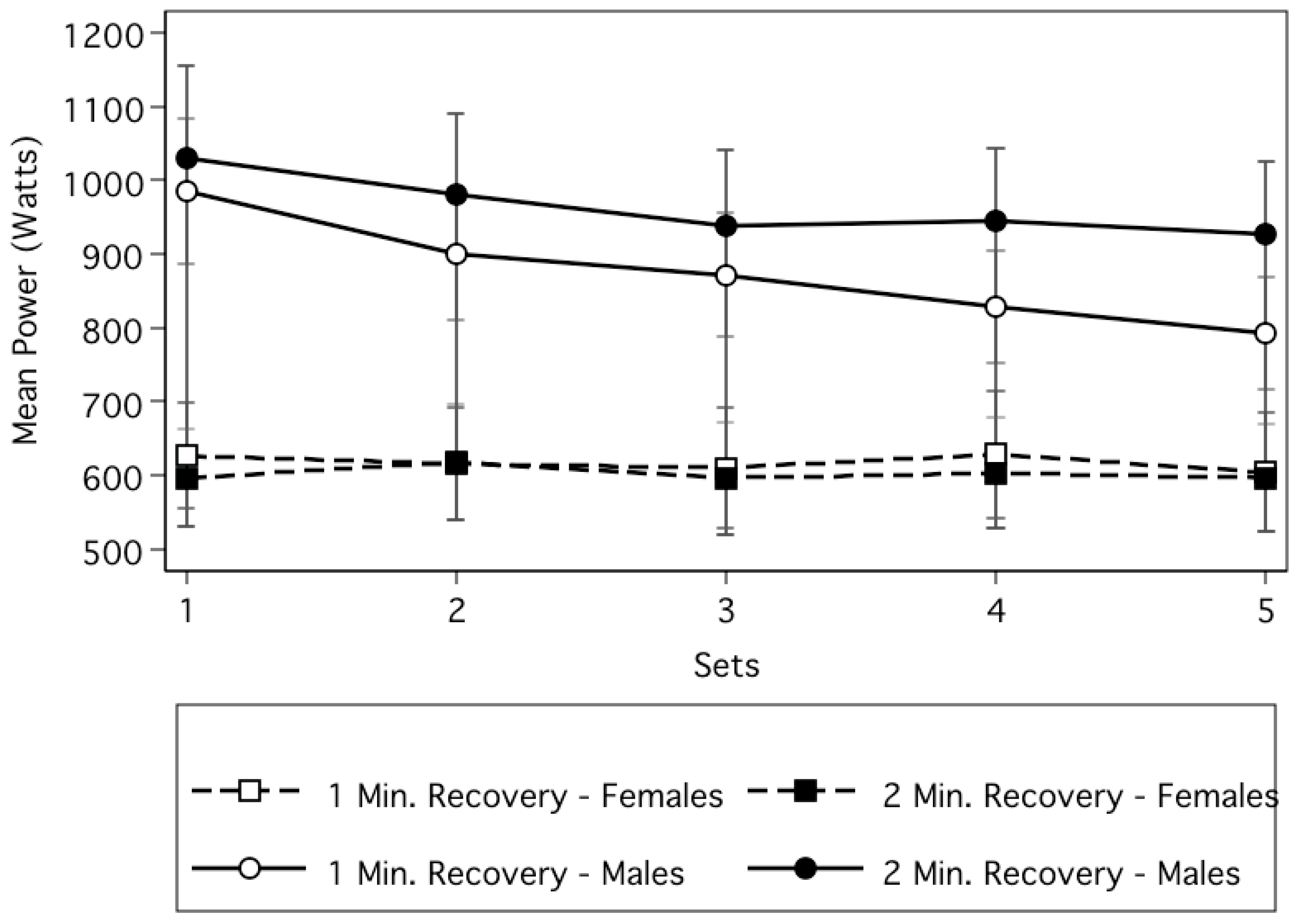

The significant interaction between sex and sets indicates that the difference in mean power among the sets is not the same for males and females (

Figure 3). From the means reported in

Table 4 for the female subjects, it appears that there were only small differences in mean power among the sets. For the one-minute recovery time, power only differed from a high of 628.2 watts to a low of 603.5 watts, and for the two-minute recovery time, power only differed from a high of 617.1 watts to a low of 596.0 watts. Neither the one-minute (

p = 0.44) nor the two-minute (

p = 0.52) recovery times resulted in a significant difference across sets for the female participants.

For the male participants, there were more substantial differences in mean power among the sets than that observed for females. For the one-minute recovery time, power differed from a high of 985.1 watts to a low of 791.9 watts, and for the two-minute recovery time, mean power differed from a high of 1029.9 watts to a low of 926.5 watts. Both the one-minute (p = 0.001) and the two-minute (p = 0.002) recovery times resulted in a significant difference across sets for the male subjects. Consequently, the female subjects generated mean power equally across all five sets, while the males generated significantly different mean power across the sets.

4. Discussion

A primary finding of this study revealed an interaction between rest periods and sets. Mean power decreased significantly across the five sets during the one-minute rest period compared to no change for the two-minute rest. The study also showed that males produced significantly more power than the females. Furthermore, an interaction occurred between sex and sets. Mean power significantly decreased across sets in the male participants, while no change occurred for the females. Lastly, within-set fatigue occurred approximately during repetitions 11–14 for the two-minute rest period and repetitions 9–11 during the one-minute rest between sets.

The novel approach of this study was the comparison of rest periods during a high-volume squat protocol for RPA. In a previous study using a low-volume protocol consisting of six sets of six repetitions at 60% 1RM after one, two, and three minutes of rest, Martorelli et al. [

22] found no change in power output between rest periods. Previous studies using higher volumes analyzed RPA with only two minutes of rest [

6,

7,

13,

23]. In agreement with the current study, Hester et al. [

6] found no change in mean power across 5 sets of 16 repetitions at 40% 1RM with two minutes of rest in recreationally resistance-trained participants. Similar results were found by Hatfield et al. [

23] using four sets of 12 with 30% 1RM during countermovement jumps. In contrast, Smilios et al. [

7] found a significant decrease in mean power during the squats in Sets 3 (~6%) and 6 (~11%) during four sets of 20 at 50% 1RM with two minutes of rest in participants with resistance training experience. The participants were unable to complete all repetitions without assistance. This modest difference observed in relative load and number of repetitions along with the similar two-minute rest period in comparing the study by Hester et al. [

6] with the current study appears to be a threshold that reduces mean power across sets in subjects with an intermediate level of resistance training. During the one-minute rest period in the current study, mean power significantly and consistently decreased by ~6–14% in Sets 2–5. No other similarly designed study using a one-minute rest period was found for comparison. Yet the level of fatigue found in this study has been shown to be effective in improving sprint and jump performance in comparison to higher levels of fatigue (≥25%) in resistance-trained males [

5].

To the current investigators’ knowledge, the investigation of sex differences in RPA within and across sets during a high-volume squat protocol is also novel. The analysis revealed that mean power significantly decreased across sets in the male participants, while no change occurred for the females. The loss of mean power primarily occurred due to the one-minute rest period. With reduced rest time between sets and likely a longer set duration compared to a low-volume set, a high demand was likely placed on the participants’ anaerobic capacity. The current data also revealed that the males lifted greater absolute loads (1RM males = 144.6 kg vs. females = 95.5 kg) and produced significantly greater mean power across sets. Thus, the greater loss in power in the males may be explained by more stress placed on the anaerobic system due to the greater absolute load and volume load produced. In support of the current findings, greater fatigue during sustained isometric contraction of the vastus medialis [

24] and lumbar muscles [

16] was found in males compared to females. A speculative mechanism is that the greater loads lifted by the males may have increased blood flow occlusion and hypoxia due to higher contraction force causing increased peripheral fatigue [

16]. A higher number of type 1 fibers in females have also been postulated [

24]. While not statistically different, the males’ greater relative strength and power output may have had a meaningful effect on fatigue. Differences in training experience favoring anaerobic capacity in the females due to training experience may also, in part, explain differences in fatigue between males and females. In addition, sex differences in pacing, neuromuscular fatigue [

25], and perception of load during fatiguing conditions may have influenced RPA. These speculations were not measured in this study and thus require further investigation.

Understanding fatigue within sets is also important when designing training programs to improve RPA. An acceptable principle in training to improve PP is to stop the set of continuous reps when a significant decrease in power output occurs. Research has revealed that a significant decrease in power occurs approximately at repetitions 5–6 using relatively heavy loads (75–80% 1RM) during the squat and power clean [

26,

27]. In addition, an accepted training principle to improve PP is to train at loads that produce PP, which has been shown to occur at ~50% 1RM during the squat [

28,

29]. Using these loads with higher-volume sets to maximize RPA is less understood. Training with squats at lighter loads [

9] and higher repetitions (10–20) with ≤20% velocity loss thresholds [

30,

31,

32] has been shown to effectively increase countermovement jump, sprint performance, and RPA. Thus, the current study included a relative load of 45% 1RM and stopped the sets when ≥ 20% loss in PP occurred for two consecutive repetitions. During the two-minute rest protocol, power output significantly decreased between repetitions 11 and 14, with a loss of PP between 13 and 17% across the five sets. During the one-minute rest period, the participants’ PP significantly decreased by 11–13% between repetitions 9 and 11. Thus, RPA was achieved to a greater extent during the 2-min recovery time with a higher volume and quality of repetitions within each set. In comparison to the current study, Hester et al. [

6] found a slightly greater power loss of 18–22% within Sets 1 through 5 of 16 repetitions at 40% 1RM with two minutes of rest during the squats in recreational trained subjects. The greater within-set fatigue in comparison to the current study was likely due to the lighter load completed to 16 repetitions by all participants. In the current study, the subjects were allowed to stop the set from volitional exhaustion; therefore, repetition data were not analyzed when more than half of the participants were unable to complete the repetitions. As a result, in the later sets, more repetitions were able to be analyzed for the two-minute rest (12–13 reps) compared to the one-minute rest (10–11 reps). The participants completing the higher number of repetitions likely had a higher anaerobic capacity, which may also explain, in part, why fatigue plateaued in some sets and within the set following repetitions when a significant decline occurred. In agreement with this, previous research has shown that fatigue plateaued during later repetitions (16–19) after a significant decrease was found during repetitions 9–12 compared to repetitions 1–5 during countermovement jumps using 30% 1RM squats in well-trained male field hockey players [

33].

Research has demonstrated that load can significantly affect the number of repetitions completed before fatigue occurs [

11]. In a study of male soldiers using individualized optimum loads based on PP with a 15% loss threshold or to failure during half squats, the subjects completed 11, 7, and 4 repetitions at the optimum load, 15% below the optimum load, and 15% above the optimum load, respectively. Further, in a study by Smilios et al. [

7] using a 5% greater relative load compared to the current study, subjects were unable to complete four sets of 20 with two minutes of rest during the squats without assistance, while also decreasing the resistance 10% in later sets. Thus, the data from the current and previous studies indicate that 10–15 repetitions would be a threshold of repetitions expected to be completed in subjects with a moderate level of resistance training using high volumes when the intention is to produce PP or near PP every repetition using relatively light loads and one to two minutes of rest between sets. However, it is important to consider when prescribing exercise for RPA that rest intervals of two minutes will likely produce greater RPA and allow more repetitions to be completed across sets.

It is important to note some limitations of the current investigation. This study included a small sample size for comparison of sex differences. The application of the data is limited to the training status of the participants who had moderate resistance training experience and should not be generalized to other populations such as elite athletes. Results may vary by requiring subjects to complete a set number of repetitions to be included in the data analysis. In the current study, sets were stopped when 20% loss in PP occurred or from volitional fatigue. It is difficult to determine the psychological influence of having an option to stop the set due to volitional fatigue on the number of repetitions capable of being completed and the amount of effort produced on each repetition. While encouragement was provided to produce maximum effort, controlling effort was not entirely possible. Physiological measures of anaerobic capacity (i.e., blood lactate) and EMG were not measured to determine mechanisms for the sex differences observed. Lastly, the velocity of the eccentric phase was not controlled, which may have varied between subjects and could have influenced concentric power. However, the pace of the eccentric phase was visually monitored, and feedback was provided to maintain consistency for all repetitions.

5. Conclusions

The data in this study indicate that the two-minute rest is better for maintaining power output across and within sets (allowing two to three more repetitions before fatigue) in comparison to one-minute rest. Sex is an important factor to consider when designing high-volume resistance training sessions, with males producing greater mean power but also experiencing greater fatigue across sets. Further, given similar relative load and rest between sets, an 11–17% loss in power within sets can be expected in participants with an intermediate level of resistance training experience. Thus, those lifting higher absolute loads and with less training experience may need to train with a minimum of two minutes of rest between sets to achieve sufficient volume for potential improvement of RPA.

RPA can be determined by the number of repetitions completed within the set at or near the set’s PP and by the ability to repeat this performance across sets. The data in this study indicate that RPA is a complex interplay of power output, volume, load, and recovery between sets. With higher power output and loads and less time to recover, fewer repetitions within and across sets are likely at or near an individual’s PP. A needs analysis of the sport and athlete is recommended to determine the optimum training protocol intended to improve the aspects of RPA.