Understanding Gameplay Acceleration Ability, Using Static Start Assessments: Have We Got It Right?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Approach to the Problem

2.2. Subjects

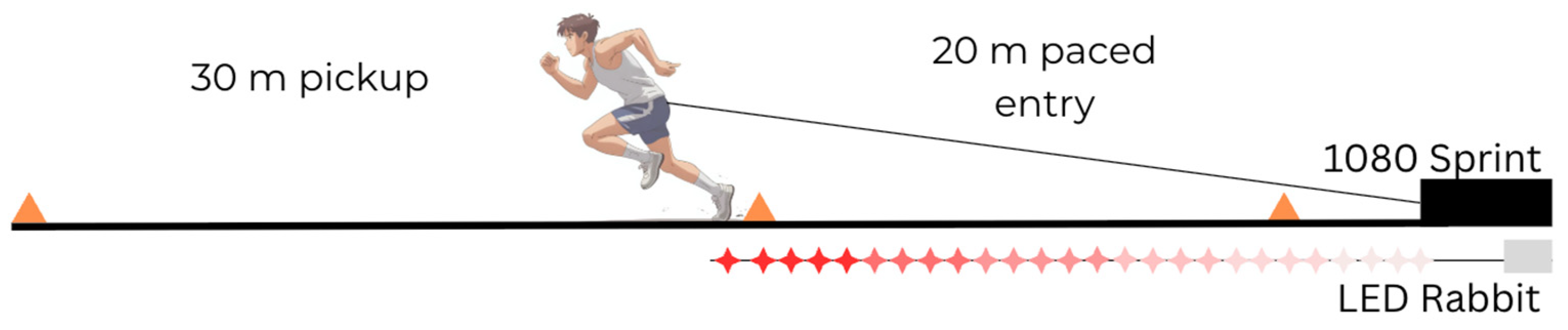

2.3. Procedures

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Practical Applications and Future Research

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| amax | Maximal acceleration |

| LED | Light emitting diode |

| LPE | Linear position encoder |

References

- Faude, O.; Koch, T.; Meyer, T. Straight sprinting is the most frequent action in goal situations in professional football. J. Sports Sci. 2012, 30, 625–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breddy, S. The Effect of Starting Velocity on Maximal Acceleration Capacity in Elite Level Youth Football Players. Master’s Thesis, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Haugen, T.; Tonnessen, E.; Hisdal, J.; Seiler, S. The role and development of sprinting speed in soccer. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2014, 9, 432–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacome, M.; Piscione, J.; Hager, J.P.; Bourdin, M. A new approach to quantifying physical demand in rugby union. J. Sports Sci. 2014, 32, 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pryer, M.; Cronin, J.; Korfist, C.; Uthoff, A. Kinetics and kinematics of pickup acceleration. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2025, 20, 2796–2804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duthie, G.M.; Pyne, D.B.; Marsh, D.J.; Hooper, S.L. Sprint patterns in rugby union players during competition. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2006, 20, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varley, M. Acceleration and Fatigue in Soccer. Ph.D. Thesis, Institute of Sport, Exercise and Active Living (ISEAL), Victoria University, Melbourne, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gabbett, T.J. Sprinting patterns of National Rugby League competition. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2012, 26, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, M.R.; Brughelli, M.; Brown, S.R.; Samozino, P.; Gill, N.D.; Cronin, J.B.; Morin, J.B. Mechanical properties of sprinting in elite rugby union and rugby league. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2015, 10, 695–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahti, J.; Jimenez-Reyes, P.; Cross, M.R.; Samozino, P.; Chassaing, P.; Simond-Cote, B.; Ahtiainen, J.; Morin, J.B. Individual Sprint Force-Velocity Profile Adaptations to In-Season Assisted and Resisted Velocity-Based Training in Professional Rugby. Sports 2020, 8, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin, J.B.; Samozino, P.; Murata, M.; Cross, M.R.; Nagahara, R. A simple method for computing sprint acceleration kinetics from running velocity data: Replication study with improved design. J. Biomech. 2019, 94, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakeman, B.; Clothier, P.J.; Gupta, A. Transition from upright to greater forward lean posture predicts faster acceleration during the run-to-sprint transition. Gait Post. 2023, 105, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonderegger, K.; Tschopp, M.; Taube, W. The challenge of evaluating the intensity of short actions in soccer: A new methodological approach using percentage acceleration. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0166534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, W.B.; Duthie, G.M.; James, L.P.; Talpey, S.W.; Benton, D.T.; Kilfoyle, A. Gradual vs. maximal acceleration: Their influence on the prescription of maximal speed sprinting in team sport athletes. Sports 2018, 6, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segers, V.; Aerts, P.; Lenoir, M.; De Clercq, D. Spatiotemporal characteristics of the walk-to-run and run-to-walk transition when gradually changing speed. Gait Post. 2006, 24, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segers, V.; Caekenberghe, I.V.; De Clercq, D.; Aerts, P. Kinematics and dynamics of burst transitions. J. Mot. Behav. 2014, 46, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segers, V.; De Smet, K.; Caekenberghe, I.V.; Aerts, P.; De Clercq, D. Biomechanics of spontaneous overground walk-to-run transition. J. Exp. Biol. 2013, 216, 3047–3054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segers, V.; Lenoir, M.; Aerts, P.; De Clercq, D. Kinematics of the transition between walking and running when gradually changing speed. Gait Post. 2007, 26, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, R.A. Comparison of Static and Dynamic Strength Increases. Res. Q. Am. Assoc. Health Phys. Educ. Recreat. 2013, 33, 329–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, B.D.; Roantree, M.T.; McCarren, A.L.; Kelly, D.T.; O’Connor, P.L.; Hughes, S.M.; Daly, P.G.; Moyna, N.M. Physiological Profile and Activity Pattern of Minor Gaelic Football Players. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2017, 31, 1811–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeting, A.J.; Cormack, S.J.; Morgan, S.; Aughey, R.J. When Is a Sprint a Sprint? A Review of the Analysis of Team-Sport Athlete Activity Profile. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feser, E.; Lindley, K.; Clark, K.P.; Bezodis, N.; Korfist, C.; Cronin, J. Comparison of two measurement devices for obtaining horizontal force-velocity profile variables during sprint running. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2022, 17, 1455–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugen, T.; Seiler, S.; Sandbakk, O.; Tonnessen, E. The Training and Development of Elite Sprint Performance: An Integration of Scientific and Best Practice Literature. Sports Med. Open 2019, 5, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pryer, M.; Cronin, J.; Neville, J.; Uthoff, A. Effect of entry velocity on pickup acceleration performance. Int. J. Strength Cond. 2025, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, D. The Basic Practice of Statistics, 9th ed.; W. H. Freeman and Company: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Mangine, G.T.; McNabb, J.A.; Feito, Y.; Van Dusseldorp, T.A.; Hester, G.M. Increased Resisted Sprinting Load Decreases Bilateral Asymmetry in Sprinting Kinetics Among Rugby Players. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2021, 35, 3076–3083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Static Start amax | 1.5 m/s−1 amax | 3.0 m/s−1 amax | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Static start amax | 0.63 (p < 0.001) | 0.34 (p = 0.06) | |

| 1.5 m/s−1 amax | 0.63 (p < 0.001) | 0.41 (p = 0.02) | |

| 3.0 m/s−1 amax | 0.34 (p = 0.06) | 0.41 (p = 0.02) |

| Static Start Entry | 1.5 m/s−1 Entry | 3.0 m/s−1 Entry | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Entry Velocity (m/s) | - | 1.62 ± 0.10 | 3.20 ± 0.18 |

| Athlete | Rank (amax; m/s−2) | Rank (amax; m/s−2) | Rank (amax; m/s−2) |

| B05 | 1 (6.05) | 1 (3.93) | 6 (2.58) |

| B02 | 2 (5.66) | 13 (3.24) | 4 (2.66) |

| B43 | 3 (5.28) | 10 (1.93) | 30 (1.93) |

| B14 | 4 (5.19) | 16 (3.18) | 18 (2.33) |

| B07 | 5 (5.10) | 19 (3.14) | 7 (2.52) |

| B11 | 6 (5.05) | 14 (3.23) | 12 (2.44) |

| B46 | 7 (5.04) | 2 (3.67) | 1 (2.82) |

| B16 | 8 (4.99) | 26 (2.24) | 21 (2.24) |

| B08 | 9 (4.89) | 4 (3.51) | 9 (2.51) |

| B03 | 10 (4.77) | 6 (3.44) | 5 (2.64) |

| B13 | 11 (4.76) | 5 (3.49) | 17 (2.35) |

| B10 | 12 (4.69) | 12 (3.26) | 10 (2.50) |

| B18 | 13 (4.53) | 24 (3.09) | 28 (2.09) |

| B17 | 14 (4.50) | 3 (3.63) | 24 (2.19) |

| B19 | 15 (4.47) | 7 (3.40) | 31 (1.92) |

| B42 | 16 (4.35) | 22 (3.11) | 3 (2.76) |

| B01 | 17 (4.34) | 9 (3.34) | 2 (2.80) |

| B34 | 18 (4.339) | 11 (3.28) | 13 (2.44) |

| B59 | 19 (4.32) | 17 (3.16) | 23 (2.21) |

| B12 | 20 (4.29) | 15 (3.22) | 14 (2.41) |

| B15 | 21 (4.25) | 8 (3.36) | 19 (2.32) |

| B36 | 22 (4.21) | 18 (3.142) | 11(2.46) |

| B39 | 23 (4.15) | 21(3.13) | 16 (2.36) |

| B40 | 24 (4.03) | 28 (3.00) | 20 (2.24) |

| B44 | 25 (4.02) | 20 (3.139) | 8 (2.52) |

| B37 | 26 (3.95) | 25 (3.04) | 26 (2.12) |

| B45 | 27 (3.93) | 30 (2.75) | 27 (2.11) |

| B60 | 28 (3.92) | 27 (3.01) | 22 (2.21) |

| B38 | 29 (3.91) | 31 (2.46) | 25 (2.15) |

| B57 | 30 (3.69) | 23 (2.40) | 15 (2.40) |

| B58 | 31 (3.52) | 29 (2.06) | 19 (2.06) |

| Mean amax (m/s−2) | 4.52 ± 0.58 | 3.21 ± 0.28 | 2.36 ± 0.24 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pryer, M.E.; Cronin, J.; Neville, J.; Mascioli, N.; Slocum, C.; Barger, S.; Uthoff, A. Understanding Gameplay Acceleration Ability, Using Static Start Assessments: Have We Got It Right? Biomechanics 2026, 6, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomechanics6010004

Pryer ME, Cronin J, Neville J, Mascioli N, Slocum C, Barger S, Uthoff A. Understanding Gameplay Acceleration Ability, Using Static Start Assessments: Have We Got It Right? Biomechanics. 2026; 6(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomechanics6010004

Chicago/Turabian StylePryer, Mark E., John Cronin, Jonathon Neville, Nick Mascioli, Chris Slocum, Sean Barger, and Aaron Uthoff. 2026. "Understanding Gameplay Acceleration Ability, Using Static Start Assessments: Have We Got It Right?" Biomechanics 6, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomechanics6010004

APA StylePryer, M. E., Cronin, J., Neville, J., Mascioli, N., Slocum, C., Barger, S., & Uthoff, A. (2026). Understanding Gameplay Acceleration Ability, Using Static Start Assessments: Have We Got It Right? Biomechanics, 6(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomechanics6010004