Abstract

Background/Objectives: Jumping is a common movement pattern, often used in testing for both performance monitoring and decision-making in return to sport. Current methods of assessing movement coordination are time-, technology- and expertise-dependent. The use of force–time curves to analyse the execution of the movement would provide an accessible and detailed analysis of movement. Methods: Thirty endurance runners and triathletes (18–40 years) completed five maximal countermovement jumps (CMJs) and five maximal standing broad jumps (SBJs). Participants were grouped (HIGH, MOD and LOW) according to the magnitude of the time interval between peak hip and peak knee extension velocity. A separate grouping according to the magnitude of the time interval between peak knee and peak ankle extension velocity was created. A one-way Statistical non-Parametric Mapping ANOVA, with alpha set at 0.05 and iterations at 10,000, was used to compare vertical ground reaction force (CMJ and SBJ), horizontal ground reaction force (SBJ) and resultant ground reaction force (SBJ) between the three hip–knee groups and a separate analysis for the three knee–ankle groups. Results: Significant differences were observed between time interval groups in both hip–knee coordination and knee–ankle coordination for both jump types (p < 0.001) at several regions of the force–time curves. Conclusions: The results suggest there is potential for statistical parametric mapping analysis to detect differences in movement coordination patterns from force curves. Further research is needed to help explain the differences observed in the curves for the kinematic groupings, to explore different combinations of hip–knee and knee–ankle kinematic patterns and to associate curve characteristics with performance indicators.

Keywords:

biomechanics; jumping; coordination; proximodistal sequencing; force curves; SPM; joint velocity; runners 1. Introduction

Jumping is often used in testing batteries within sport and exercise settings for a variety of purposes such as performance monitoring, prehabilitation, rehabilitation, return-to-sport decisions [1,2] and as a means of monitoring fatigue and training readiness [3]. The high volume of published work focusing on jumping highlights its versatility as a neuromuscular performance testing modality. The increased availability of high-quality, portable force plates also suggests the use of jump force data in both sports and general settings is likely to increase [1,4].

Typical force plate use, to quantify human performance utilises, discrete outcome measures focusing on achieving bigger, higher and faster jumps. These discrete outcome measures include, but are not limited to, peak force, jump height (calculated), rate of force development, eccentric to concentric ratio and peak power [5,6,7,8,9]. These variables provide useful insight into specific aspects of jumping and can be easily interpreted by most practitioners. However, selecting single points or areas on the force curve overlooks the interdependency of data points and may neglect valuable information [10]. For example, peak force is a frequently isolated metric used to assess jump performance, yet several studies have indicated that while sufficient force is needed to accelerate the centre of mass (COM), very high peak force does not always predict high jump heights [6,11,12,13,14]. Without an understanding of how an individual executes the movement, practitioners run the risk of missing the technical underpinnings that may be limiting athlete performance and/or the effectiveness of programming or coaching interventions.

The triple-extension movement pattern characterised by proximodistal sequencing has been shown to contribute to jump height during maximal-effort countermovement jumps (CMJs) in both simulation and experimental settings [15,16]. Proximal to distal sequencing is evident in activities such as running, horizontal jumping, powerlifting and upper body movements like throwing [17,18,19,20,21,22]. All these movements, categorised as “power” movements, aim to produce both high force and high velocity during execution [19,20,23,24]. Utilising the higher force capacity of the bigger moments of inertia belonging to proximally located muscles allows development of large angular acceleration, which can then be propagated down the kinetic chain to smaller segments with smaller moments of inertia [25]. This proximodistal sequencing enables angular velocities of the distal joint to be greater than can be achieved with isolated muscle contractions while simultaneously maintaining or increasing the initial muscular force. The unique combination of very high velocity and high force from proximodistal sequencing explains why many power movements utilise this movement pattern [26,27]. Execution of these movements requires coordination of multiple joints which will impact the power applied to the ground or object and the discrete outcome measures extracted. Force–time curves encode the fluctuations in the acceleration of the centre of mass resulting from individual joint acceleration and inter-joint coordination. The fluctuations in force data will also be influenced by length of muscles, anthropometry, muscle isoforms, neurological activation and previous skill development [28,29].

Recent developments in statistical analysis approaches for extensive time-series data, such as statistical parametric mapping (SPM) have fostered opportunity to explore the use of force–time-series data in the assessment of movement patterns and coordination [10]. Statistical parametric mapping, adapted from brain neuroimaging for use in biomechanics, allows researchers to use standard statistical analysis methods to compare continuous data sets [30]. SPM has been proposed as a statistical method to identify strategy-based differences in jumping performance [31,32,33] and could delve into the differences in the shape of force–time curves observed during countermovement jumps [34,35,36,37]. Vertical ground reaction force from CMJs is the most commonly reported outcome for lower limb power movement [10]. However, most human movement and locomotion is multiplanar [38,39]. Given horizontal jumps such as standing broad jumps (SBJs) incorporate both horizontal and vertical force and power, and have strong correlations with running performance [40,41,42], it seems logical that horizontal jumps should also be analysed alongside vertical jumps when assessing power.

Analysis of lower limb power movements using triple extension has predominantly been through measurement of single variables or variables collected at a discrete point in time during jump performance. SPM permits an alternate approach that allows analysis of the quality of the movement and sequencing using a quantitative approach. The aim of this study was to determine if specific kinematic coordination variables resulted in identifiable differences in the jump force–time curves of runners.

2. Materials and Methods

A convenience sample of thirty participants (height 173.77 ± 8.33 cm, body mass 68.7 ± 12.3 kg, age 22.2 ± 4.3 yr, n = 16 female) were recruited for this study. Participants had no lower limb injuries within the previous six months and no illness in the two weeks prior to testing [43]. Subjects were asked to refrain from strenuous physical activity 12–24 h prior to testing [44]. The study was approved by the institutes’ Ethics Committee (HES00142) and followed ethical practices and guidelines from the Declaration of Helsinki, and participants provided their written informed consent prior to commencing the study.

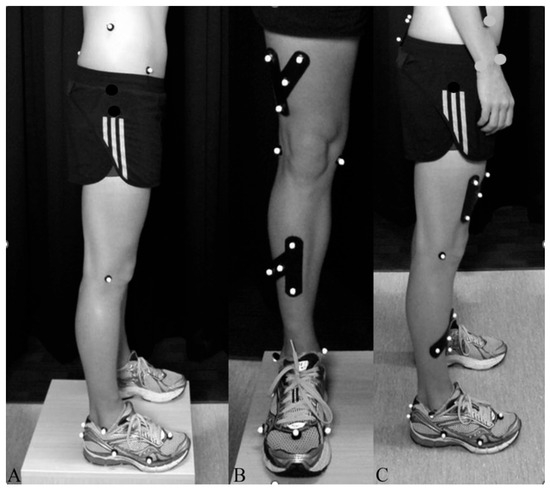

Upon arrival, retroreflective markers were attached to the lower body and pelvis using International Society of Kinanthropometry methods for landmark location [45], shown in Figure 1 [46]. Force data from dual in-ground AMTI force plates (AMTI HPS-SC, Advanced Mechanical Technology Inc., Watertown, MA, USA) measuring at 1000 Hz and movement data from six Bonita and six Vero cameras (100 Hz) were captured synchronously using VICON Nexus software (V2.15, Vicon Motion Systems Ltd., Oxford, UK), and gaps were filled. Lower body joints were modelled using Visual 3D (v4.91.0 C-motion, Kingston, ON, Canada) prior to calculation of joint angular velocities. Marker trajectories were filtered using a bidirectional Butterworth filter with a cut-off frequency of 10 Hz [47]. Trials with insufficient markers for modelling throughout the whole trial were disregarded, resulting in one jumper being excluded (n = 29).

Figure 1.

Lower body marker locations without and with tracking clusters, modified with permission. Photo credit: Prof. Patria Hume. From Lorimer et al., 2018 [46]. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.5845/fig-2. Reproduced under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Licence (CC BY 4.0).

A ten-minute warm up consisting of five minutes of jogging at a self-selected pace, lunges and leg swings was followed by equipment and subject static calibration. Athletes were then instructed to complete three practice CMJs and SBJs to allow for familiarisation with the jumps prior to data collection. Athletes were instructed to jump as high as possible for the countermovement jumps, contacting the force plate for both take-off and landing [48]. For the standing broad jumps, athletes were instructed to jump as far as possible, with starting positions adjusted to ensure both take-off and landing were captured by the two force plates. Hands were kept on the waist throughout all jumps to eliminate the effect of an arm swing. Athletes completed five CMJs interspersed with 30 s of passive rest. Two minutes of rest was given before performing five SBJs with 30 s of rest between recorded jumps [12,31]. Jump height was calculated as the difference in displacement from standing to the highest point reached by the COM, and jump distance was extracted from the difference in displacement of the left posterior iliac spine marker from starting position to finish.

Hip, knee and ankle extension velocity were plotted over time [49,50], and the absolute time of peak hip, knee and ankle angular velocity with reference to take-off were extracted [51]. The time interval between peak hip extension velocity and peak knee extension velocity was calculated, as was the time interval between peak knee extension velocity and peak ankle extension velocity. The reliability of the time intervals from trial one to trial five was good for the knee–ankle interval (ICC 0.67–0.83) and poor for the hip–knee interval (ICC 0.34–0.69). The average time interval under both conditions was calculated across all five jump trials. Participants were ranked from greatest time interval to smallest time interval for peak hip–knee extension velocity (H-K) for the left side and then the right side, before being divided into three groups: high (HIGH), moderate (MOD) and low (LOW). Individuals were removed if both the left and right joint time intervals did not fall into the same group. The process was repeated for the knee–ankle peak extension time interval (K-A). As a result, participants were not necessarily in the same group for H-K and K-A time intervals. The final group numbers and group characteristics are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of groups when grouped according to the average interval (±SD) for time delay between peak angular extension velocity in neighbouring joints for countermovement and standing broad jumps, with mean differences and effect sizes between the HIGH and MOD groups and the MOD and LOW groups.

All force data was processed via a custom python script in Spyder (v5.5.1, The Scientific Python Development Environment). Participants’ vGRF was normalised to body weight (BW), and times coinciding with the lowest point of the countermovement and the start of flight time, when force first drops below 20 N, were extracted. The initiation of flight time was selected when force dropped below 20 N due to the reported reliability of this absolute value as a vertical force threshold [52]. All force curves, vertical and horizontal, were cut between these two distinct time points, ensuring all of the concentric phase was captured [48]. The cut force was then interpolated to 101 points with no additional filtering to avoid smoothing of acceleration variations related to the pattern of movement and allow easier comparison between individuals’ force curves. Linear interpolation was used; however, caution should be exercised when interpreting results as distortion of features can occur with this process [31]. Upon confirmation of jump consistency, force curves were averaged for each participant’s five CMJ vGRF values and five SBJ vGRF (Fz), hGRF (Fy) and GRF (FR) values. Two participants had only four jumps included, and one participant had three jumps included for kinematic grouping and further kinetic analysis due to incomplete data.

Areas of statistical difference between the force curves of the three groups were investigated using the spm1d open-source software package v0.4.18 (http://www.spm1d.org, accessed 10 October 2023) [53]. A non-parametric one-way ANOVA, to account for differences in group numbers, was conducted, comparing force curves for the three H-K groups and then for the three K-A groups. For all non-parametric tests, alpha (α) was set to 0.05 and iterations were set to 10,000 [54,55]. When the critical threshold was exceeded, the null hypothesis was rejected, resulting in statistical significance and supraclusters. Further non-parametric post hoc tests (SnPM{t}) were conducted for all jumps and groups when significance was reached and supraclusters were identified. The Bonferroni correction was removed to increase sensitivity and likelihood of discovering true effects within groups, based on the methods of Papi and co-workers [54], current limitations of ANOVA post hoc analysis within SPM software v0.4.18 and the exploratory nature of the study. However, the risk of false positives is increased with removal of the Bonferroni correction, and results should be interpreted with caution.

3. Results

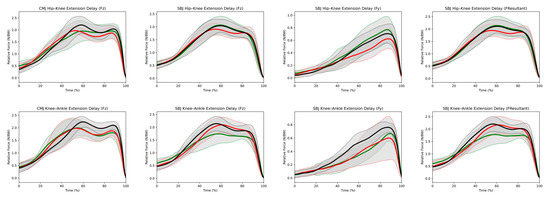

The force–time curves grouped according to the magnitude of the time interval between peak hip and peak knee extension velocity or peak knee and peak ankle extension velocity showed areas of statistical significance for both vertical and horizontal jumps. Multiple supraclusters were present for each of the countermovement jumps and standing broad jumps, and both joint coordination pairs (H-K and K-A) reached significance during the concentric phase of take-off when analysing the force–time curves. It is apparent that, regardless of whether the movement patterns are grouped according to the hip–knee coordination timing or the knee–ankle coordination timing, inter-group differences in force–time curves are present (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Mean force curves and standard deviation clouds for all jump types (CMJ and SBJ) in all directions of force (Fz, Fy, FR). The top row represents Hip—Knee delay and the bottom row is Knee—Ankle delay. The HIGH group is green, LOW group is black and MOD group is red. The grey outlines represent the standard deviation cloud for each group. Force is normalised to body weight (BW) for any vertical force (Fz), horizontal force (Fy) is normalised to body weight (BW) and resultant force uses normalised values of both (Fz) and (Fy).

3.1. CMJ

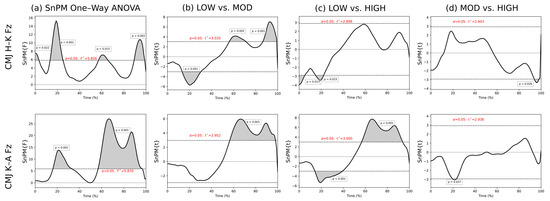

The one-way ANOVA SnPM analysis of the CMJs established four supraclusters of statistical significance across the early (0–4%, p = 0.022; 13–25% p = 0.001), mid (57–66% p = 0.015) and late (89–99% p = 0.002) phases of the force–time curves when grouped according to the hip–knee peak extension velocity time interval, and two supraclusters in the early (16–33%, p < 0.001) and mid–late (57–97%, p < 0.001) regions when the knee–ankle time interval was used (Figure 3a). Post hoc analysis of the hip–knee grouping indicated that the MOD time interval group had a greater force magnitude early in the force–time curve (14–30%, p < 0.001) compared to the LOW group (Figure 3b). However, across the mid (56–71%, p = 0.002) and late (87–99%, p < 0.001) regions of the force curve, the force magnitude was higher in the LOW time interval group (Figure 3b,c). When grouped by the time interval of peak knee–ankle extension velocity there was significantly higher force early in the concentric phase for the HIGH group compared to the LOW time interval group (14–40%, p < 0.001; Figure 3c). The force was significantly higher in the LOW group throughout the mid-to-late phase of the movement prior to take-off compared to both the MOD and HIGH time interval groups (57–98%, p < 0.001; 57–94%, p < 0.001; Figure 3b,c).

Figure 3.

SnPM one-way ANOVA results (a) and post hoc tests (b–d) for CMJ H-K (top row) and CMJ K-A (bottom row). Supraclusters (grey) and critical threshold (dashed lines) are shown. Column (b) is interaction between LOW and MOD, column (c) is interaction between LOW and HIGH and column (d) is interaction between MOD and HIGH. F* = critical threshold for ANOVA; t* = critical threshold for post-hoc t-test.

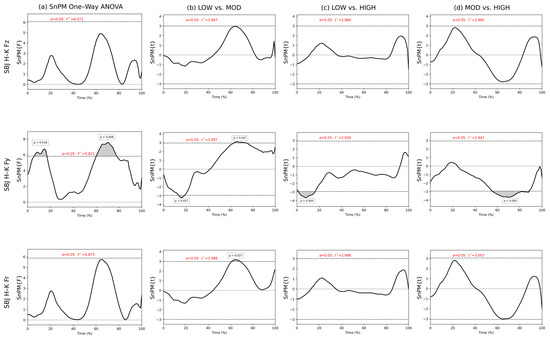

3.2. SBJ H-K

When the force curves were grouped according to the hip–knee peak extension velocity time intervals for the SBJs, no supraclusters were evident in the vertical force or resultant force. In contrast, the analysis of horizontal force reveals differences early and mid-to-late in the time interval of 6–17% (p = 0.018) and 60–78% (p = 0.006) force (Figure 4a). Post hoc testing showed a region in the mid phase of the force curves in the Fy curve where the MOD time interval group had significantly lower force than the LOW time interval group (63–74%, p = 0.012; Figure 4b). The HIGH time interval group produced significantly higher horizontal force than the MOD group in the mid-to-late region of the movement (55–88%, p = 0.002; Figure 4d).

Figure 4.

SnPM one-way ANOVA results (a) and post hoc tests (b–d) for SBJ H-K Fz (top row), Fy (middle row) and FR (bottom row). Supraclusters (grey) and critical threshold (dashed lines) are shown. Column (b) is interaction between LOW and MOD, column (c) is interaction between LOW and HIGH and column (d) is interaction between MOD and HIGH. F* = critical threshold for ANOVA; t* = critical threshold for post-hoc t-test.

3.3. SBJ K-A

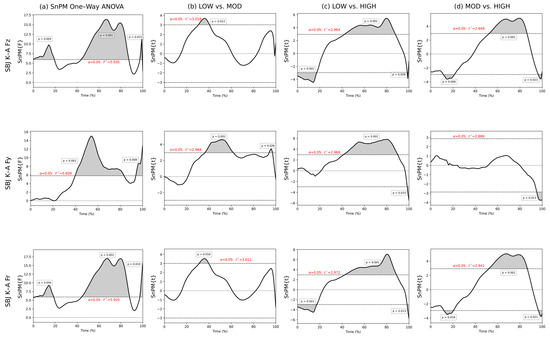

When the SBJ force–time curves were compared according to knee–ankle peak extension velocity time interval, three supraclusters were present in the Fz across the early (0–19% p = 0.004), mid (44–87% p < 0.001) and final (97–100% p = 0.015) portions of the movement, and two supraclusters were present within the Fy during mid-to-late movement (40–83% p < 0.001; 94–100% p = 0.008; Figure 5a). Post hoc analysis showed significantly greater vertical force for the LOW time interval group compared to the MOD (31–40%, p = 0.012) and HIGH (43–88%, p < 0.001) groups, while the MOD time interval group had significantly greater vertical force than the HIGH group later on the curve (53–86%, p < 0.001; Figure 5b–d).

Figure 5.

SnPM one-way ANOVA results (a) and post hoc tests (b–d) for SBJ K-A Fz (top row), Fy (middle row) and FR (bottom row). Supraclusters (grey) and critical threshold (dashed lines) are shown. Column (b) shows interaction between LOW and MOD, column (c) shows interaction between LOW and HIGH and column (d) shows interaction between MOD and HIGH. F* = critical threshold for ANOVA; t* = critical threshold for post-hoc t-test.

In terms of horizontal (Fy) and resultant force (FR), the largest supraclusters occurred through the middle of the concentric phase (40–83% p < 0.001; 44–88% p < 0.001). This was due to the significantly greater force produced by the LOW time interval group compared to both the MOD (Fy 36–62%, p = 0.001; FR 31–40%, p = 0.016) and HIGH (Fy 42–90%, p < 0.001) (FR 43–88%, p < 0.001) time interval groups (Figure 5b,c).

4. Discussion

The results of the present study support the hypothesis that differences in the absolute time delay for proximodistal joint coordination produce statistical differences in the force–time curves of horizontal and vertical jumps. The results provide initial evidence for the potential of continuous data statistical analysis methods in identification of differences in multi-segment coordination of complex movements using force curves. The main findings of this study were (1) the LOW knee–ankle time interval group had points of significantly higher force across the mid-to-late region of the force–time curve than the HIGH and MOD groups; (2) the HIGH and LOW hip–knee time interval groups had comparable force–time curves, which were greater than the MOD group and suggest that differing jump strategies may be capable of generating similar force–time curves. Further research is required to understand the exact mechanisms behind the observed differences in the force curves and links between differences in the force curves and jump performance. The following explanations for the observed differences are speculative, based on previous research into jumping mechanics.

It is apparent from the mean force curves that when grouped according to the duration of the time interval between hip–knee and knee–ankle peak joint extension velocity, there were observable differences in the shape of the force–time curves (Figure 2). Moreover, one-way SnPM ANOVA identified areas of significant differences when comparing high-, moderate- and low-time-interval groups for CMJs in the vertical force–time curve and both the vertical and horizontal force–time curves for the SBJs (Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5). Accordingly, fluctuations in the force–time curve and changes in the magnitude and/or timing of peaks may be related to alterations in kinematic coordination of the joints, with resultant effects on the motion of the centre of mass.

Generating sufficient force to accelerate the centre of mass off the ground is vital for jump performance [14]. Discrete metrics, such as peak force, have been purported to provide limited ability to predict jump performance when analysed in isolation [56]. From a purely theoretical perspective, the ability to produce high force over a prolonged period when jumping increases the impulse and the change in the momentum of the centre of mass, leading to a greater take-off velocity. Likewise, producing high force over a short duration results in greater neuromuscular power and energy transfer to the centre of mass. Therefore, the area under the force–time curve as well as the timing of peak force relative to take-off may be important for producing the greatest flight, whether that flight is for vertical (CMJ) or a combination of vertical and horizontal (SBJ) displacement.

There was a notably lower force early in the movement in the low-time-interval knee–ankle group, followed by a later peak with a significantly greater magnitude (p < 0.001, 57–97%) than moderate- and high-time-interval groups during CMJs. A similar trend was apparent in the vertical force for the SBJs (p < 0.001, 44–87%). The similarity in vertical force between different jump modes may reflect the requirement of high vertical force to maximise flight time in both jumps. However, the requirement for horizontal motion in the SBJ likely alters the timing of the hip, knee and ankle movement, resulting in a moderate knee–ankle time interval, producing comparable vertical forces to the low group. Nonetheless, from a purely force-based perspective, the significant supraclusters observed in the latter half of the jump for Fz in both the CMJ and SBJ knee–ankle groupings generally indicate a greater force production when the joint-coupling time interval is low. A higher relative force immediately prior to take-off may produce greater take-off velocity, reflecting a greater continuous upwards acceleration of the centre of mass. There are several mechanisms that could explain the variations in force–time data and movement outcomes in the present study.

Studies have shown that the shorter the delay in transition between the eccentric and concentric phases of a movement, the greater the contribution of the stretch–shortening cycle to the performance outcome [57,58,59]. The ability to maximise the contribution of stored elastic energy is often defined as the reactive strength index (RSI), where a high RSI represents the ability to smoothly transition from eccentric to concentric contraction with a minimal delay or amortisation phase [60]. A brief amortisation phase attenuates the loss of energy for elastic recoil through stress relaxation [61]. The capacity to maximise stored elastic energy contribution in plantar flexors at the ankle may explain the higher vertical force magnitude observed with low compared with moderate or high time intervals at the knee–ankle joints. More rapid acceleration at the knee–ankle could conceivably result in shorter transition time between eccentric and concentric contraction of the plantar flexors, allowing greater elastic energy contributions at the ankle. Improvement in jump performance due to contributions from stretch–shortening cycle actions is well established through previous studies comparing CMJ and squat jumps, where the extended pause at the bottom of the squat movement when performing the squat jump reduces the jump height [7,26].

Work by de Graaf and co-workers [62] has shown that greater ankle power production is generated during a CMJ compared to an extended-knee/straight-leg jump that predominantly isolates the muscle group contribution to the jump to the Triceps Surae. While some of the difference in ankle power between CMJ and straight-leg jumps can be attributed to the aforementioned stretch–shortening cycle, the transfer of torque and momentum from the hip and knee during a CMJ means the power produced at the ankle exceeds the capacity of the Triceps Surae muscle group alone [25]. Indeed, simulation studies indicate that force transfers via biarticular muscles down the kinetic chain, together with contraction of monoarticular muscles in each limb segment, generate additive forces to the movement [25,63]. While some of the muscular force is lost within the kinetic chain, the outcome is a large torque production acting at the ankle and at a higher velocity than can be achieved by the active contractile apparatus of the muscles.

The anatomical properties of the gastrocnemius and soleus, together with the Achilles tendon, work favourably with a shorter delay between the extension of the knee and plantar flexion of the ankle [63]. This interaction is prominent in the model proposed by van Ingen Schenau [64] which depicts the gastrocnemius acting like a rigid wire and the vastii group as a spring. When the knee extends, the ankle is rapidly forced into plantarflexion, shortly thereafter converting any stored elastic energy from the countermovement to mechanical energy. Bobbert [63] also described the role of the Triceps Surae in jumping as requiring a compliant tendon for the ankle to achieve rapid, high angular velocities. This mechanism is often described as a whip-like action, in part because of the structure of long, compliant tendons that is also seen in proximodistal sequencing of the upper limb [17,20]. The high velocity achieved from the whip-like action through the limb segments and the high torque generated in the final 10% of the movement result in high power production immediately before the centre of mass leaves the ground when jumping. As noted by Dowling and Vamos [14], while high force is necessary, it is only when high force is combined with high velocity that maximal power is produced and peak jump performance is obtained.

Finally, a smooth transfer of angular momentum down the kinetic chain will facilitate a steadily increasing application of force into the ground, culminating in a single peak force before a rapid drop in force as the centre of mass is launched into the air. Such force–time curves have been described as unimodal and reported to be the most effective for jump performance [34,65]. Bimodal force–time curves have been reported, where two peaks separated by a short decrease in force occur, and the resultant highest peak force can be observed in either the first or the second peak. In the present study, the averaged CMJ force curves for all groups generally show bimodal force–time curves, although the high-hip–knee-time-interval group had a smoother curve with broader fluctuations rather than notable peaks and valleys. Normalisation of time as a percentage when visualising the curves, where 100% is the take-off of the jump, may alter the shape of the curve to a small degree [30,31]. Regardless, the valley between peaks in a bimodal force curve indicates a deceleration of the centre of mass despite continuing to move upwards in the concentric phase. In a movement that requires maximal force and velocity for optimal performance, deceleration not only reduces the velocity of the movement but also decreases the magnitude of the peak force that can be produced. It is plausible that a pause in the transfer of force down the kinetic chain is responsible for the deceleration noted in bimodal curves; however, more work is required to corroborate this theory. Identifying where the disruption in the transfer of force occurs in the kinetic chain would provide the foundation to develop interventions that improve the coordination of the jump movement.

There are several possible mechanisms that might explain the high-hip–knee-time-interval group achieving a force throughout the late jump movement phase which was comparable to the low-time-interval-group in the CMJs (Fz) and SBJs across the Fz, Fy and FR directions of force. Increased countermovement depth and range of motion will determine the lower limb muscles’ capacity to generate force, as dictated by the length–tension curve [58,66,67]. The effect of countermovement depth is supported by the previous studies [15,68]), which have shown that increasing the active range throughout which a muscle can contract benefits jumping performance because the muscle’s ability to actively produce force is extended. Moreover, there is a short latent period for muscle excitation and actin–myosin cross-bridge cycling to generate muscle contraction, so a longer duration of movement is useful to redress the delay and augment force output. Accordingly, a greater time interval between peak hip and peak knee extension velocity in the high-time-interval-group of the present study could facilitate latent period redress and promote active state concentric propulsion, where torque originates predominantly from the gluteus maximus, providing an alternate mechanism to achieve similar performance outcomes as the low-time-interval group. In contrast, the low-hip–knee-time-interval group may have attained its performance outcome through rapid knee extension driven by the vastii muscle group to shorten the time interval required to reach peak velocity. In turn, the knee may have then reached a critical extension angle shortly after hip extension, which triggers take-off and allows more effective utilisation of Achilles-stored elastic energy in a movement pattern where torque is predominantly produced from quadricep muscle contractions [15]. The rapid acceleration may have led to greater force observed on the force–time curve. Alternately, the low-time-interval group may simply have better muscular power to quickly produce force through hip extension. This ability could be attributed to both modifiable and non-modifiable factors, such as training history or muscle fibre type.

Maximising the active state for muscular contraction is beneficial for monoarticular muscles like the gluteus maximus, which plays a role in instigating the transfer of energy and generation of force to be transferred distally by biarticular muscles, including the hamstring group, rectus femoris and gastrocnemius [69]. The property of biarticular muscles crossing two joints enables the muscle to act pseudo-isometrically; i.e., movement at one joint related to muscle shortening occurs simultaneously with muscle lengthening at a second joint. As such, when the gluteus maximus contracts in the propulsive phase of jumping it can contribute to mechanical work of distal joints via transfer of the muscular force produced along the biarticular conduits [15,27]. Monoarticular muscles at each subsequent joint can add additional force, resulting in very high force at the terminal joint. Therefore, greater monoarticular muscle activation in the early stages of the jump could also be promoting the higher magnitudes of force observed within the supraclusters in the high-time-interval groups.

Whilst CMJs and SBJs share similarities in terms of the joint sequencing in movement execution, an interesting point to note in the present study was the moderate-knee–ankle-time-interval group producing similar force curves to that of the low knee–ankle group in SBJ vertical and resultant force. The alternate outcomes at the knee–ankle for SBJs versus CMJs could potentially be due to the initial hip, knee and ankle positioning in preparation for the propulsive phase and a greater total angular displacement at the ankle due to a more forward positioning of the centre of mass and greater flexion, particularly at the ankle. Moreover, the force generated may be similar regardless of whether there are low or moderate knee–ankle peak extension velocity time intervals, but a high time interval produces a distinct vertical force–time curve in SBJs [23,70,71]. Importantly, there was greater variability in the horizontal compared to vertical jump execution, which indicates that a specificity of movement pattern should be considered when selecting training modalities for either horizontal or vertical movements, as well as a need for a deeper understanding of the interaction of both directions of force output on desired performance. The purpose of the research was to determine whether differences in the coordination of the joints when performing a complex multi-segment movement resulted in measurable differences in the force–time curve. Further research is needed to identify which combination of hip to knee and knee to ankle coordination is optimal for maximal jump height or jump distance, whether this can be consistently linked to differences in the force curves and the mechanisms behind these differences.

4.1. Limitations

Due to the inherent variability of human subjects and the exploratory nature of this study, there were several limitations that should be acknowledged when interpreting the results. Firstly, the current sample size and subsequent group numbers may have limited the interpretation of the results. While the initial number of participants included for data analysis was n = 29, inconsistencies between left and right joint extension velocities and the short time intervals used for grouping participants resulted in group numbers being uneven. Equally, the sample was, by design, relatively homogenous, within this study of the range of jumping ability that focused specifically on runners. Therefore, the ability to generalise findings across the general and athlete populations is impacted. Another limitation of the results is the separation of hip, knee and ankle extension to two joint couples. Jump performance is dependent on the unified coordination of all three joints, and in future studies, all three joints and how they interact could be considered; however, much larger sample sizes would be required to capture all possible combinations sufficiently.

The calculation of the hip–knee and knee–ankle delays as absolute metrics may have been a limitation that overlooked individual variability in grouping. An alternate method that could account for variability in jump duration, femur and shank length, subsequent available angular displacement, and the relative timing of peak hip, knee and ankle extension velocity could be calculated in reference to movement duration. Other methods of quantifying coordination such as timing of initiation of joint movement or timing of peak torque may also provide different groupings and insight into the mechanics of jumping. Finally, all the current explanations proposed are theoretically based, and electromyography (EMG) would be needed to provide physiological data to support any of the proposed contributions of various muscle groups to jump performance.

It is acknowledged that the hip to knee time interval showed greater variability within each participant compared to the knee to ankle time interval, potentially resulting in a wider standard deviation for the force curves for both the CMJ H-K and the SBJ H-K analysis. As with traditional ANOVA statistics, a larger standard deviation reduces the chance of statistical significance being reached. Further differences in the force curve may be apparent in more homogeneous groups. The higher variability in the hip to knee time interval compared to the knee to ankle time interval may further reflect the capacity to modify the coordination strategy to achieve a similar outcome as an individual fatigues.

4.2. Future Applications and Use

There is scope for further research and application in a sporting performance context based on the findings of this study. Increased force production over the entirety of a jump can benefit jump performance [72]. By fostering a deeper understanding of how movement pattern execution enhances force production, it allows for a more tailored approach to training muscles and coordination. Equally, this study highlights that various movement strategies can achieve similar force outcomes and the importance of understanding the mechanisms that led to the final product. Particularly in clinical settings or fatigue and readiness monitoring, muscular deficits or changes in movement strategy may be masked when only observing discrete metrics [31]. Improved understanding of how the shape of the curve can highlight changes in the holistic movement pattern may provide more nuanced assessment of athletes and consequently more targeted training approaches [31,73]. Overall, SPM has demonstrated a strong ability to evaluate and differentiate between different performances across continuous data sets, like jumping. The opportunity for progression within the research exists to continue refining how groups and populations are compared.

5. Conclusions

Execution of a jump requires the complex coordination of physiological, structural and neurological components to achieve take-off from the ground. Principles of self-organisation suggest there are likely multiple techniques that produce high or long jump performance in humans. Due to the necessity of high forces and the time-course of force application that results in movement of the COM, a comprehensive understanding of fluctuations and differing shapes in the force–time curve may provide more refined analysis of movement and an enhanced understanding of how to improve performance. The present study highlights that various movement strategies can achieve similar force outcomes when jumping, and it is important to understand the mechanisms that led to the final performance. Overall, group differences were detected on force–time curves when categorised by a pre-defined kinematic grouping variable for CMJs and SBJs. Both a high and low time interval delay between hip and knee peak extension velocity produced greater magnitudes in the concentric phase of the vertical force–time curve, whereas a low time delay between knee and ankle peak extension velocity consistently produced significantly different force curves compared to the high and moderate groups for each jump type. These outcomes support the use of SPM and SnPM as viable tools to dissect movement strategies in different jump types within a population to better understand the association between kinetics and kinematics in movement.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.S. and A.L.; methodology, H.S., V.C. and A.L.; software, H.S. and A.L.; validation, H.S. and A.L.; formal analysis, H.S. and A.L.; investigation, H.S. and A.L.; resources, H.S. and A.L.; data curation, H.S. and A.L.; writing—original draft preparation, H.S.; writing—review and editing, H.S., V.C. and A.L.; visualisation, H.S., V.C. and A.L.; supervision, V.C. and A.L.; project administration, H.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Bond University (HES00142 approved 3 August 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data can be made available upon request to the authors.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this study, the author(s) used Microsoft 365 Copilot for the purposes of code construction within Python. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 1D | One-dimensional |

| 2D | Two-dimensional |

| 3D | Three-dimensional |

| COM | Centre of mass |

| BM | Body mass |

| CMJ | Countermovement jump |

| EMG | Electromyography |

| FR | Resultant force |

| Fy | Horizontal force (anterior–posterior) |

| Fz | Vertical force |

| HIGH | Largest time interval between joint extension velocities |

| H-K | Time interval between peak hip extension velocity and peak knee extension velocity |

| K-A | Time interval between peak knee extension velocity and peak ankle extension velocity |

| LOW | Smallest time interval between joint extension velocities |

| MOD | Intermediate time interval between joint extension velocities |

| RFD | Rate of force development |

| RFT | Random field theory |

| RSIMod | Modified reactive strength index |

| SBJ | Standing broad jump |

| SJ | Squat jump |

| SPM | Statistical parametric mapping |

| SnPM | Statistical non-parametric mapping |

| vGRF | Vertical ground reaction force |

References

- Mylonas, V.; Chalitsios, C.; Nikodelis, T. Validation of a Portable Wireless Force Platform System To Measure Ground Reaction Forces During Various Tasks. Int. J. Sports Phys. Ther. 2023, 18, 1283–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufano, J.J.; Malecek, J.; Steffl, M.; Stastny, P.; Hojka, V.; Vetrovsky, T. Field-Based and Lab-Based Assisted Jumping: Unveiling the Testing and Training Implications. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claudino, J.G.; Cronin, J.; Mezêncio, B.; McMaster, D.T.; McGuigan, M.; Tricoli, V.; Amadio, A.C.; Serrão, J.C. The Countermovement Jump to Monitor Neuromuscular Status: A Meta-Analysis. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2017, 20, 397–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles-Palazón, F.J.; Comfort, P.; Ripley, N.J.; Herrington, L.; Bramah, C.; McMahon, J.J. Force Plate Methodologies Applied to Injury Profiling and Rehabilitation in Sport: A Scoping Review Protocol. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0292487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harry, J.; Krzyszkowski, J.; Chowning, L.; Kipp, K. Phase-Specific Force and Time Predictors of Standing Long Jump Distance. J. Appl. Biomech. 2021, 37, 400–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirby, T.J.; McBride, J.M.; Haines, T.L.; Dayne, A.M. Relative Net Vertical Impulse Determines Jumping Performance. J. Appl. Biomech. 2011, 27, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozinc, Ž.; Žitnik, J.; Smajla, D.; Šarabon, N. The Difference between Squat Jump and Countermovement Jump in 770 Male and Female Participants from Different Sports. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2022, 22, 985–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBride, J.M.; Kirby, T.J.; Haines, T.L.; Skinner, J.W.; Delalija, A. Relationship Between Impulse, Peak Force and Jump Squat Performance with Variation in Loading and Squat Depth. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2011, 25, S77–S78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinchi, K.; Yamashita, D.; Yamagishi, T.; Aoki, K.; Miyamoto, N. Relationship between Jump Height and Lower Limb Joint Kinetics and Kinematics during Countermovement Jump in Elite Male Athletes. Sports Biomech. 2024, 23, 3454–3465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pataky, T.C. Generalized N-Dimensional Biomechanical Field Analysis Using Statistical Parametric Mapping. J. Biomech. 2010, 43, 1976–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gheller, R.G.; Dal Pupo, J.; Ache-Dias, J.; Detanico, D.; Padulo, J.; dos Santos, S.G. Effect of Different Knee Starting Angles on Intersegmental Coordination and Performance in Vertical Jumps. Hum. Mov. Sci. 2015, 42, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBride, J.M.; Kirby, T.J.; Haines, T.L.; Skinner, J. Relationship Between Relative Net Vertical Impulse and Jump Height in Jump Squats Performed to Various Squat Depths and With Various Loads. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2010, 5, 484–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Castilla, A.; Rojas, F.J.; Gómez-Martínez, F.; García-Ramos, A. Vertical Jump Performance Is Affected by the Velocity and Depth of the Countermovement. Sports Biomech. 2021, 20, 1015–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dowling, J.J.; Vamos, L. Identification of Kinetic and Temporal Factors Related to Vertical Jump Performance. J. Appl. Biomech. 1993, 9, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobbert, M.F.; van Soest, A.J. Why Do People Jump the Way They Do? Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 2001, 29, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bobbert, M.F.; van Ingen Schenau, G.J. Coordination in Vertical Jumping. J. Biomech. 1988, 21, 249–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atwater, A.E. Biomechanics of Overarm Throwing Movements and of Throwing Injuries. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 1979, 7, 43–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cushion, E.J.; Warmenhoven, J.; North, J.S.; Cleather, D.J. Principal Component Analysis Reveals the Proximal to Distal Pattern in Vertical Jumping Is Governed by Two Functional Degrees of Freedom. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2019, 7, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirashima, M.; Yamane, K.; Nakamura, Y.; Ohtsuki, T. Kinetic Chain of Overarm Throwing in Terms of Joint Rotations Revealed by Induced Acceleration Analysis. J. Biomech. 2008, 41, 2874–2883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, C.A. Sequential Motions of Body Segments in Striking and Throwing Skills: Descriptions and Explanations. J. Biomech. 1993, 26 (Suppl. S1), 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, C.A. A Segment Interaction Analysis of Proximal-to-Distal Sequential Segment Motion Patterns. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1991, 23, 130–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, I.; Lee, H.-D. Joint Coordination and Muscle-Tendon Interaction Differ Depending on The Level of Jumping Performance. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2023, 22, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukashiro, S.; Besier, T.F.; Barrett, R.; Cochrane, J.; Nagano, A.; Lloyd, D.G. Direction Control in Standing Horizontal and Vertical Jumps. Int. J. Sport Health Sci. 2005, 3, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schache, A.G.; Blanch, P.D.; Dorn, T.W.; Brown, N.A.T.; Rosemond, D.; Pandy, M.G. Effect of Running Speed on Lower Limb Joint Kinetics. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2011, 43, 1260–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Soest, A.J.; Schwab, A.L.; Bobbert, M.F.; van Ingen Schenau, G.J. The Influence of the Biarticularity of the Gastrocnemius Muscle on Vertical-Jumping Achievement. J. Biomech. 1993, 26, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, R.; Bobbert, M.F.; van Ingen Schenau, G.J. Mechanical Output from Individual Muscles during Explosive Leg Extensions: The Role of Biarticular Muscles. J. Biomech. 1996, 29, 513–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prilutsky, B.I.; Zatsiorsky, V.M. Tendon Action of Two-Joint Muscles: Transfer of Mechanical Energy between Joints during Jumping, Landing, and Running. J. Biomech. 1994, 27, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cushion, E.J.; North, J.S.; Cleather, D.J. Differences in Motor Control Strategies of Jumping Tasks, as Revealed by Group and Individual Analysis. J. Mot. Behav. 2022, 54, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, S.K.; Angadi, S.S.; Bhargava, A.; Harper, J.; Hirschberg, A.L.; Levine, B.D.; Moreau, K.L.; Nokoff, N.J.; Stachenfeld, N.S.; Bermon, S. The Biological Basis of Sex Differences in Athletic Performance: Consensus Statement for the American College of Sports Medicine. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2023, 55, 2328–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honert, E.C.; Pataky, T.C. Timing of Gait Events Affects Whole Trajectory Analyses: A Statistical Parametric Mapping Sensitivity Analysis of Lower Limb Biomechanics. J. Biomech. 2021, 119, 110329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, S.; Warmenhoven, J.; Haff, G.G.; Chapman, D.W.; Nimphius, S. Countermovement Jump and Squat Jump Force-Time Curve Analysis in Control and Fatigue Conditions. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2022, 36, 2752–2761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, L.P.; Connick, M.; Haff, G.G.; Kelly, V.G.; Beckman, E.M. The Countermovement Jump Mechanics of Mixed Martial Arts Competitors. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2020, 34, 982–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warmenhoven, J.; Harrison, A.; Robinson, M.A.; Vanrenterghem, J.; Bargary, N.; Smith, R.; Cobley, S.; Draper, C.; Donnelly, C.; Pataky, T. A Force Profile Analysis Comparison between Functional Data Analysis, Statistical Parametric Mapping and Statistical Non-Parametric Mapping in on-Water Single Sculling. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2018, 21, 1100–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guess, T.M.; Gray, A.D.; Willis, B.W.; Guess, M.M.; Sherman, S.L.; Chapman, D.W.; Mann, J.B. Force-Time Waveform Shape Reveals Countermovement Jump Strategies of Collegiate Athletes. Sports 2020, 8, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, R.A.; Drake, D. Is a Bimodal Force-Time Curve Related to Countermovement Jump Performance? Sports 2018, 6, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozinc, Ž. Is the Shape of the Force-Time Curve Related to Performance in Countermovement Jump? A Review. Crit. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2022, 50, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lake, J.P.; McMahon, J.J. Within-Subject Consistency of Unimodal and Bimodal Force Application during the Countermovement Jump. Sports 2018, 6, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eng, J.J.; Winter, D.A. Kinetic Analysis of the Lower Limbs during Walking: What Information Can Be Gained from a Three-Dimensional Model? J. Biomech. 1995, 28, 753–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClay, I.; Manal, K. Three-Dimensional Kinetic Analysis of Running: Significance of Secondary Planes of Motion. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1999, 31, 1629–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietze-Hermosa, M.; Montalvo, S.; Gonzalez, M.; Rodriguez, S.; Cubillos, N.; Dorgo, S. Association and Predictive Ability of Jump Performance with Sprint Profile of Collegiate Track and Field Athletes. Sports Biomech. 2021, 23, 2137–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hudgins, B.; Scharfenberg, J.; Triplett, N.T.; McBride, J.M. Relationship Between Jumping Ability and Running Performance in Events of Varying Distance. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2013, 27, 563–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junge, N.; Jørgensen, T.B.; Nybo, L. Performance Implications of Force-Vector-Specific Resistance and Plyometric Training: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2023, 53, 2447–2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayne, H.; Cockcroft, J.; Robyn, A.; Louw, Q. Objective Classification of Countermovement Jump Force-Time Curve Modality: Within Athlete-Consistency and Associations with Jump Performance. Sports Biomech. 2021, 23, 2053–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcbride, J.M.; Snyder, J.G. Mechanical Efficiency and Force-Time Curve Variation during Repetitive Jumping in Trained and Untrained Jumpers. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2012, 112, 3469–3477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, A.; Marfell-Jones, M.; Olds, T.; Ridder, H. International Standards for Anthropometric Assessment, 3rd ed.; International Society for the Advancement of Kinanthropometry: Lower Hutt, New Zealand, 2011; ISBN 978-0-620-36207-8. [Google Scholar]

- Lorimer, A.V.; Keogh, J.W.L.; Hume, P.A. Using Stiffness to Assess Injury Risk: Comparison of Methods for Quantifying Stiffness and Their Reliability in Triathletes. PeerJ 2018, 6, e5845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erer, K.S. Adaptive Usage of the Butterworth Digital Filter. J. Biomech. 2007, 40, 2934–2943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzyszkowski, J.; Chowning, L.D.; Harry, J.R. Phase-Specific Verbal Cue Effects on Countermovement Jump Performance. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2022, 36, 3352–3358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavda, S.; Bromley, T.; Jarvis, P.; Williams, S.; Bishop, C.; Turner, A.; Lake, J.; Mundy, P. Force-Time Characteristics of the Countermovement Jump: Analyzing the Curve in Excel. Strength Cond. J. 2018, 40, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrigan, J.J.; Stone, J.D.; Galster, S.M.; Hagen, J.A. Analyzing Force-Time Curves: Comparison of Commercially Available Automated Software and Custom MATLAB Analyses. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2022, 36, 2387–2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, L.; Bryanton, M.; Moolyk, A. Proximal-to-Distal Sequencing in Vertical Jumping With and Without Arm Swing. J. Strength Cond. Res. Natl. Strength Cond. Assoc. 2014, 28, 1195–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SMITH, J.C.; LAMONT, H.S.; BAREFOOT, M. Comparison of Different Take-off Thresholds When Assessing Vertical Jump Performance. Int. J. Exerc. Sci. 2024, 17, 660–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pataky, T.C. Rft1d: Smooth One-Dimensional Random Field Upcrossing Probabilities in Python. J. Stat. Softw. 2016, 71, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papi, E.; Bull, A.M.J.; McGregor, A.H. Alteration of Movement Patterns in Low Back Pain Assessed by Statistical Parametric Mapping. J. Biomech. 2020, 100, 109597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pataky, T.C.; Vanrenterghem, J.; Robinson, M.A. Zero- vs. One-Dimensional, Parametric vs. Non-Parametric, and Confidence Interval vs. Hypothesis Testing Procedures in One-Dimensional Biomechanical Trajectory Analysis. J. Biomech. 2015, 48, 1277–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnston, L.A.; Butler, R.J.; Sparling, T.L.; Queen, R.M. A Single Set of Biomechanical Variables Cannot Predict Jump Performance Across Various Jumping Tasks. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2015, 29, 396–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, F.C.; Pandy, M.G. Storage and Utilization of Elastic Strain Energy during Jumping. J. Biomech. 1993, 26, 1413–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobbert, M.F.; Gerritsen, K.G.; Litjens, M.C.; Van Soest, A.J. Why Is Countermovement Jump Height Greater than Squat Jump Height? Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1996, 28, 1402–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hooren, B.; Zolotarjova, J. The Difference Between Countermovement and Squat Jump Performances: A Review of Underlying Mechanisms With Practical Applications. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2017, 31, 2011–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, L.; Harry, J.; Mercer, J. Relationships Between Countermovement Jump Ground Reaction Forces and Jump Height, Reactive Strength Index, and Jump Time. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2018, 32, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, T.J. Contribution of Elastic Tissues to the Mechanics and Energetics of Muscle Function during Movement. J. Exp. Biol. 2016, 219, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Graaf, J.B.; Bobbert, M.F.; Tetteroo, W.E.; van Ingen Schenau, G.J. Mechanical Output about the Ankle in Countermovement Jumps and Jumps with Extended Knee. Hum. Mov. Sci. 1987, 6, 333–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bobbert, M.F.; Huijing, P.A.; van Ingen Schenau, G.J. A Model of the Human Triceps Surae Muscle-Tendon Complex Applied to Jumping. J. Biomech. 1986, 19, 887–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ingen Schenau, G.J. From Rotation to Translation: Constraints on Multi-Joint Movements and the Unique Action of Bi-Articular Muscles. Hum. Mov. Sci. 1989, 8, 301–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.-T.; Song, C.-Y.; Chen, Z.-R.; Wang, I.-L.; Gu, C.-Y.; Wang, L.-I. Differences Between Bimodal and Unimodal Force-Time Curves During Countermovement Jump. Int. J. Sports Med. 2019, 40, 663–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bobbert, M.F.; Casius, L.J.R. Is the Effect of a Countermovement on Jump Height Due to Active State Development? Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2005, 37, 440–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domire, Z.J.; Challis, J.H. The Influence of Squat Depth on Maximal Vertical Jump Performance. J. Sports Sci. 2007, 25, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobbert, M.F.; Casius, L.J.R.; Sijpkens, I.W.T.; Jaspers, R.T. Humans Adjust Control to Initial Squat Depth in Vertical Squat Jumping. J. Appl. Physiol. 2008, 105, 1428–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBride, J.M. Muscle Actuators, Not Springs, Drive Maximal Effort Human Locomotor Performance. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2021, 20, 766–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagano, A.; Komura, T.; Fukashiro, S. Optimal Coordination of Maximal-Effort Horizontal and Vertical Jump Motions—A Computer Simulation Study. Biomed. Eng. OnLine 2007, 6, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakai, M.; Linthorne, N.P. Optimum Take-off Angle in the Standing Long Jump. Hum. Mov. Sci. 2005, 24, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cormie, P.; McBride, J.M.; McCaulley, G.O. Power-Time, Force-Time, and Velocity-Time Curve Analysis of the Countermovement Jump: Impact of Training. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2009, 23, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nüesch, C.; Roos, E.; Egloff, C.; Pagenstert, G.; Mündermann, A. The Effect of Different Running Shoes on Treadmill Running Mechanics and Muscle Activity Assessed Using Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM). Gait Posture 2019, 69, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).