Effects of Weight-Bearing-Induced Changes in Tibial Inclination Angle on Varus Thrust During Gait in Female Patients with Knee Osteoarthritis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

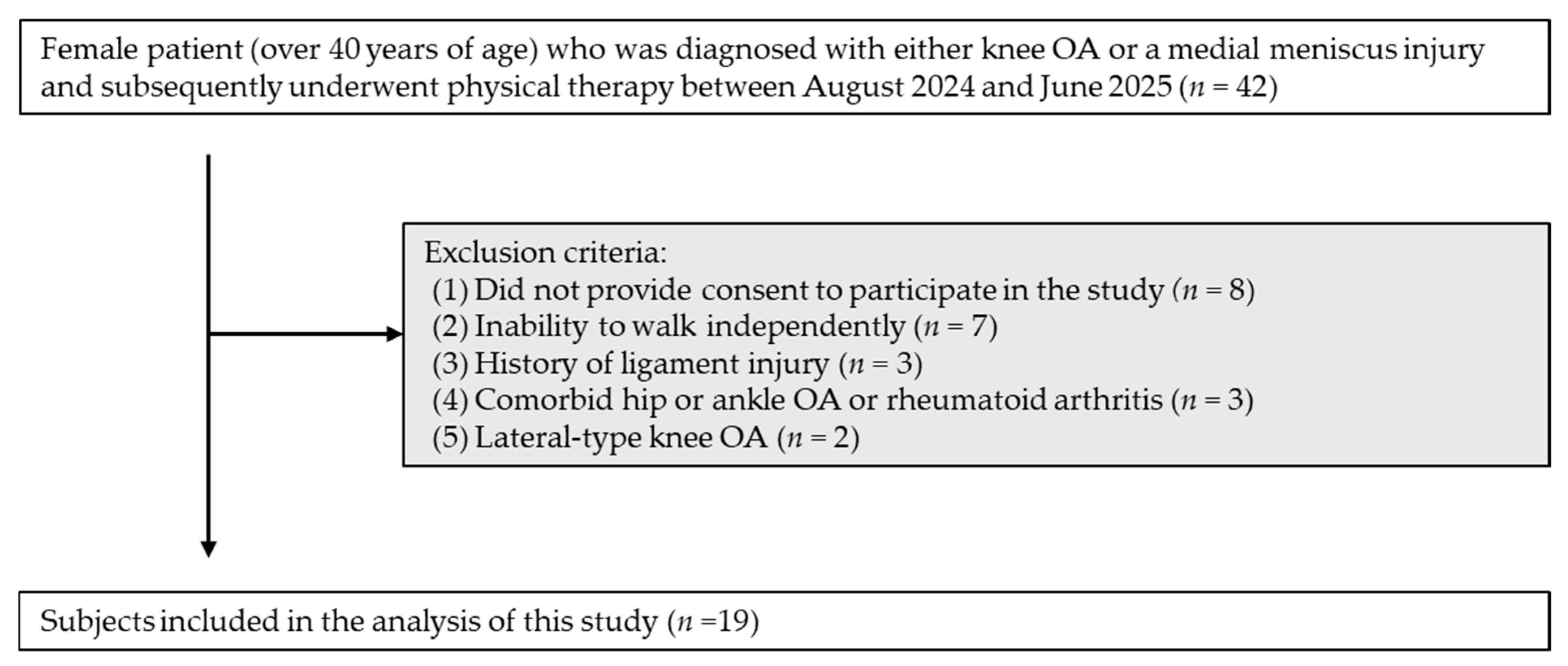

2.1. Participants

2.2. Tasks

2.3. Measurement Procedures

2.3.1. TA

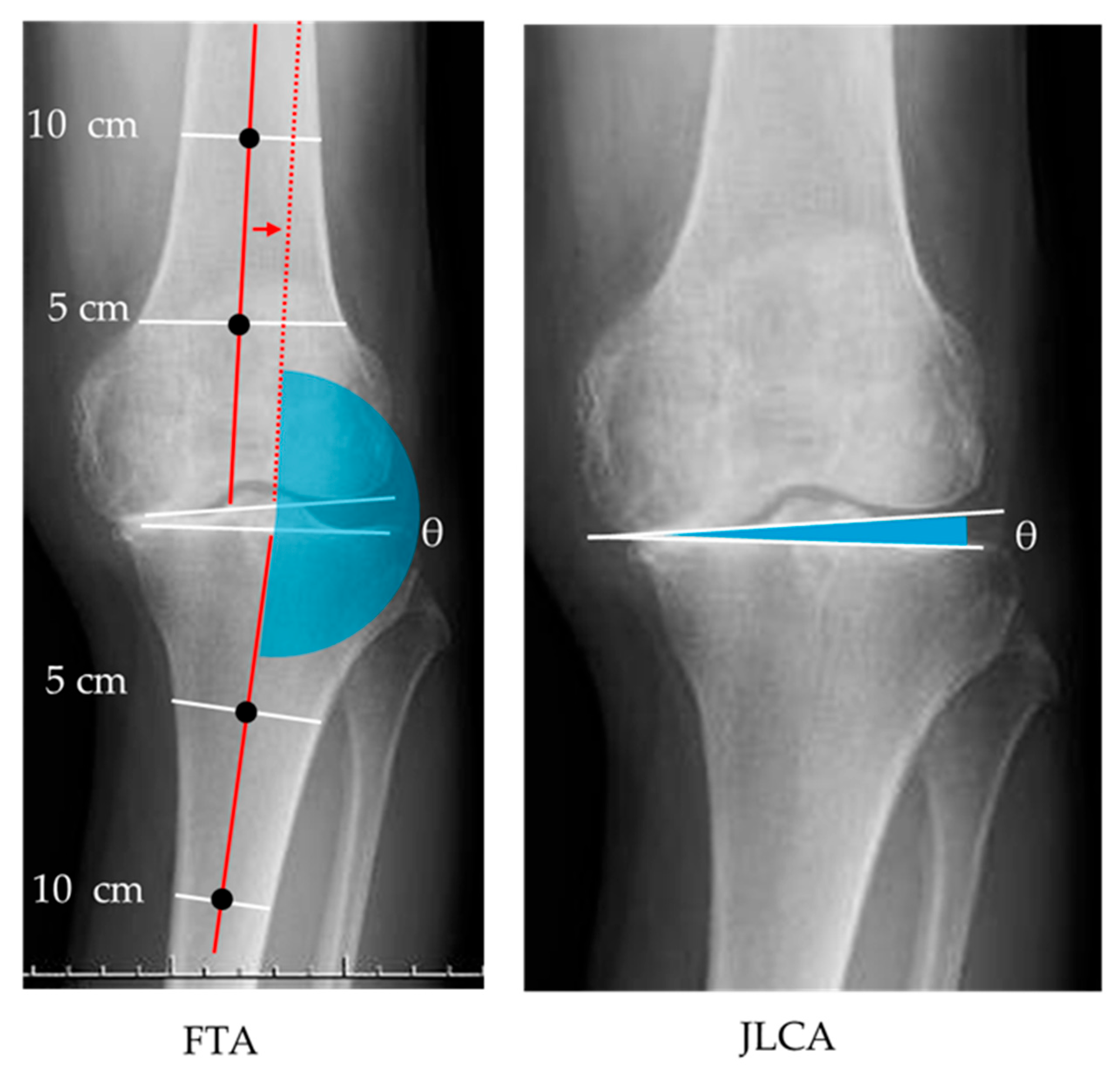

2.3.2. Radiographic Images

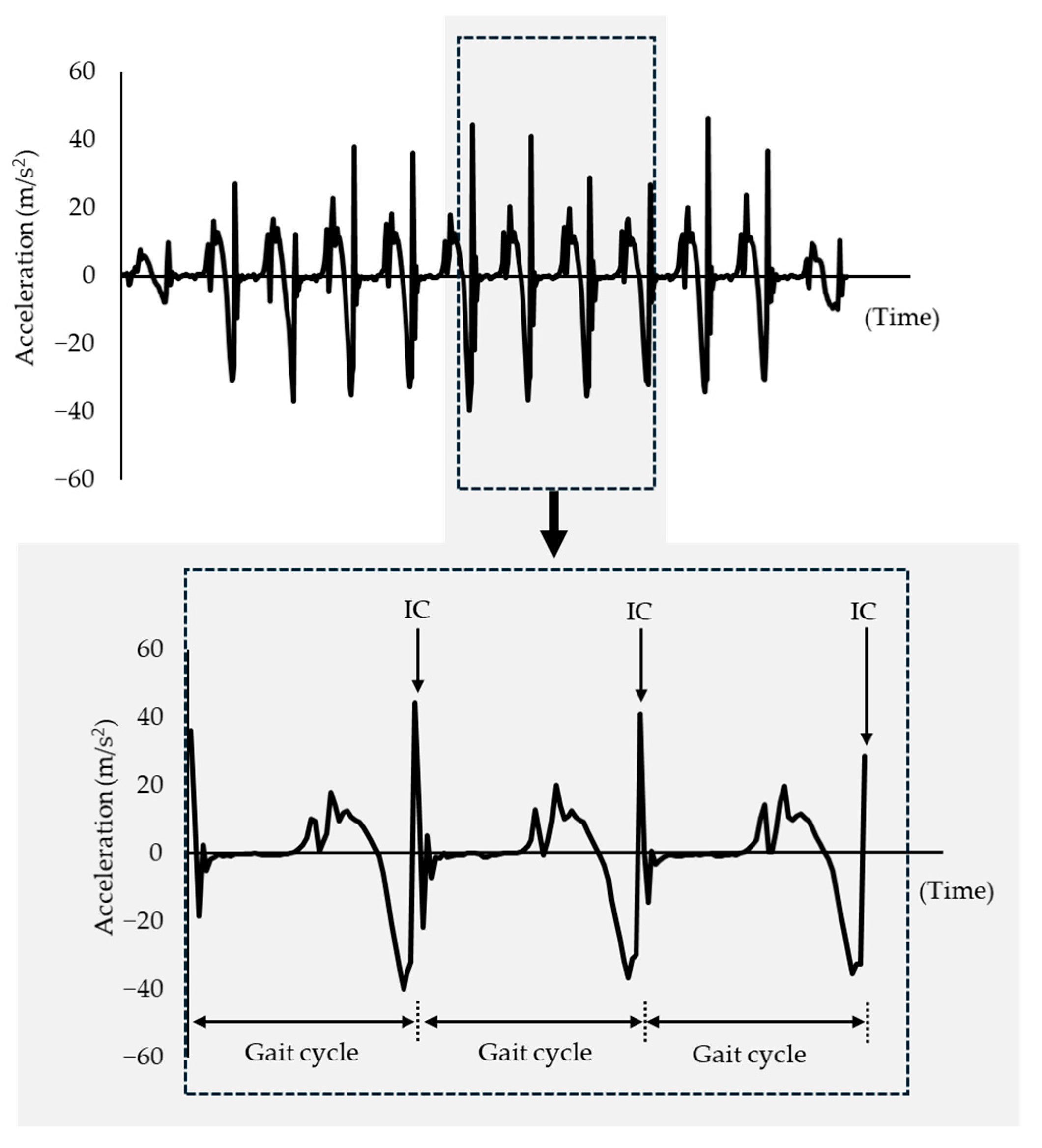

2.3.3. VT Measurement During Gait Using IMU Sensors

2.4. Data Analysis

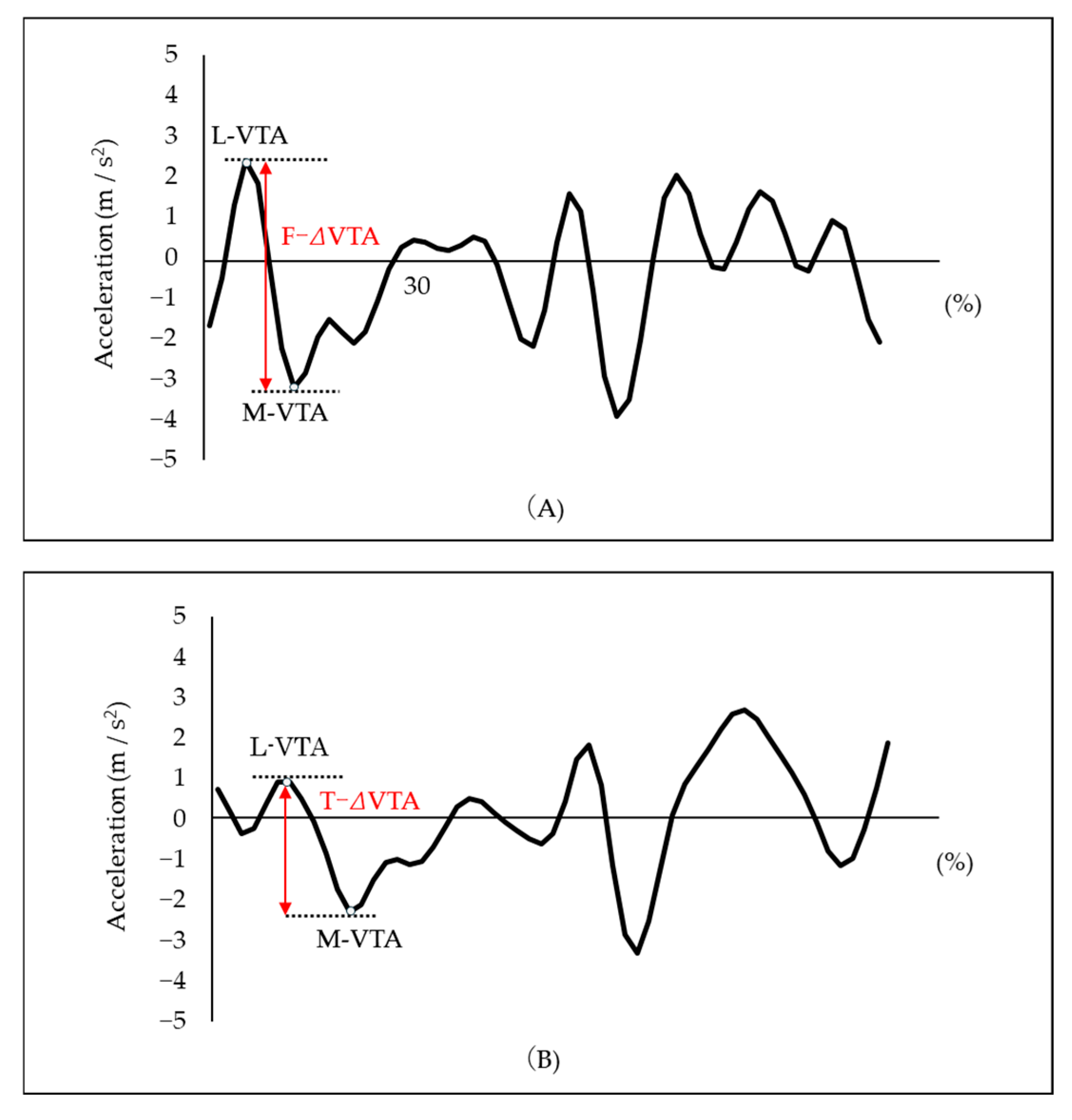

VTA of the Thigh and Tibia

2.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. TA, Radiographic Parameters, and VTA During Gait

3.2. Association Between the Standing TA and Radiographic Parameters

3.3. Effect of the ΔTA on the F-ΔVTA and the T-ΔVTA

4. Discussion

4.1. Association Between the Standing TA and Radiographic Images

4.2. Influence of the ΔTA on the ΔVTA

4.3. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chang, A.; Hayes, K.; Dunlop, D.; Hurwitz, D.; Song, J.; Cahue, S.; Genge, R.; Sharma, L. Thrust during Ambulation and the Progression of Knee Osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2004, 50, 3897–3903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, A.H.; Chmiel, J.S.; Moisio, K.C.; Almagor, O.; Zhang, Y.; Cahue, S.; Sharma, L. Varus Thrust and Knee Frontal Plane Dynamic Motion in Persons with Knee Osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2013, 21, 1668–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishii, Y.; Ishikawa, M.; Kurumadani, H.; Hayashi, S.; Nakamae, A.; Nakasa, T.; Sumida, Y.; Tsuyuguchi, Y.; Kanemitsu, M.; Deie, M.; et al. Increase in Medial Meniscal Extrusion in the Weight-Bearing Position Observed on Ultrasonography Correlates with Lateral Thrust in Early-Stage Knee Osteoarthritis. J. Orthop. Sci. 2020, 25, 640–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukamoto, H.; Saito, K.; Matsunaga, T.; Iwami, T.; Saito, H.; Kijima, H.; Akagawa, M.; Komatsu, A.; Miyakoshi, N.; Shimada, Y. Diagnostic Accuracy of the Mobile Assessment of Varus Thrust Using Nine-Axis Inertial Measurement Units. Prog. Rehabil. Med. 2021, 6, 20210009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsurumiya, K.; Hayasaka, W.; Komatsu, A.; Tsukamoto, H.; Suda, T.; Iwami, T.; Shimada, Y. Quantitative Evaluation Related to Disease Progression in Knee Osteoarthritis Patients During Gait. Adv. Biomed. Eng. 2021, 10, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misu, S.; Tanaka, S.; Ishihara, K.; Asai, T.; Nishigami, T. Applied Assessment Method for Varus Thrust during Walking in Patients with Knee Osteoarthritis Using Acceleration Data Measured by an Inertial Measurement Unit. Sensors 2022, 22, 6460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foroughi, N.; Smith, R.M.; Lange, A.K.; Baker, M.K.; Singh, M.A.F.; Vanwanseele, B. Dynamic Alignment and Its Association with Knee Adduction Moment in Medial Knee Osteoarthritis. Knee 2010, 17, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, K.E.; Eigenbrot, S.; Geronimo, A.; Guermazi, A.; Felson, D.T.; Richards, J.; Kumar, D. Quantifying Varus Thrust in Knee Osteoarthritis Using Wearable Inertial Sensors: A Proof of Concept. Clin. Biomech. 2020, 80, 105232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyazaki, T.; Wada, M.; Kawahara, H.; Sato, M.; Baba, H.; Shimada, S. Dynamic Load at Baseline Can Predict Radiographic Disease Progression in Medial Compartment Knee Osteoarthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2002, 61, 617–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennell, K.L.; Bowles, K.-A.; Wang, Y.; Cicuttini, F.; Davies-Tuck, M.; Hinman, R.S. Higher Dynamic Medial Knee Load Predicts Greater Cartilage Loss over 12 Months in Medial Knee Osteoarthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2011, 70, 1770–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, G.H.; Harvey, W.F.; McAlindon, T.E. Associations of Varus Thrust and Alignment with Pain in Knee Osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2012, 64, 2252–2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iijima, H.; Fukutani, N.; Aoyama, T.; Fukumoto, T.; Uritani, D.; Kaneda, E.; Ota, K.; Kuroki, H.; Matsuda, S. Clinical Phenotype Classifications Based on Static Varus Alignment and Varus Thrust in Japanese Patients with Medial Knee Osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015, 67, 2354–2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukutani, N.; Iijima, H.; Fukumoto, T.; Uritani, D.; Kaneda, E.; Ota, K.; Aoyama, T.; Tsuboyama, T.; Matsuda, S. Association of Varus Thrust With Pain and Stiffness and Activities of Daily Living in Patients With Medial Knee Osteoarthritis. Phys. Ther. 2016, 96, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wink, A.E.; Gross, K.D.; Brown, C.A.; Guermazi, A.; Roemer, F.; Niu, J.; Torner, J.; Lewis, C.E.; Nevitt, M.C.; Tolstykh, I.; et al. Varus Thrust during Walking and the Risk of Incident and Worsening Medial Tibiofemoral MRI Lesions: The Multicenter Osteoarthritis Study. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2017, 25, 839–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, R.E.; Andersen, M.S.; Harlaar, J.; Van Den Noort, J.C. Relationship between Knee Joint Contact Forces and External Knee Joint Moments in Patients with Medial Knee Osteoarthritis: Effects of Gait Modifications. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2018, 26, 1203–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wink, A.E.; Gross, K.D.; Brown, C.A.; Lewis, C.E.; Torner, J.; Nevitt, M.C.; Tolstykh, I.; Sharma, L.; Felson, D.T. Association of Varus Knee Thrust During Walking With Worsening Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index Knee Pain: A Prospective Cohort Study. Arthritis Care Res. 2019, 71, 1353–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchison, L.; Grayson, J.; Hiller, C.; D’Souza, N.; Kobayashi, S.; Simic, M. Relationship Between Knee Biomechanics and Pain in People With Knee Osteoarthritis: A Systematic Review and meta-analysis. Arthritis Care Res. 2023, 75, 1351–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misu, S.; Tanaka, S.; Miura, J.; Ishihara, K.; Asai, T.; Nishigami, T. Association of the Degree of Varus Thrust during Gait Assessed by an Inertial Measurement Unit with Patient-Reported Outcome Measures in Knee Osteoarthritis. Sensors 2023, 23, 4578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuroyanagi, Y.; Nagura, T.; Kiriyama, Y.; Matsumoto, H.; Otani, T.; Toyama, Y.; Suda, Y. A Quantitative Assessment of Varus Thrust in Patients with Medial Knee Osteoarthritis. Knee 2012, 19, 130–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wada, M.; Miyazaki, T.; Yamamoto, Y.; Sakamoto, T.; Adachi, T. Correlation of Knee Instability with Alignment and Repetitive Physical Activity in Patients with Knee Osteoarthritis: A Cross-Sectional Study. Preprint 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschmann, A.; Buck, F.M.; Fucentese, S.F.; Pfirrmann, C.W.A. Upright CT of the Knee: The Effect of Weight-Bearing on Joint Alignment. Eur. Radiol. 2015, 25, 3398–3404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanwanseele, B.; Parker, D.; Coolican, M. Frontal Knee Alignment: Three-Dimensional Marker Positions and Clinical Assessment. Clin. Orthop. 2009, 467, 504–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, M.A.; Bennell, K.L. Predicting Dynamic Knee Joint Load with Clinical Measures in People with Medial Knee Osteoarthritis. Knee 2011, 18, 231–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zampogna, B.; Vasta, S.; Amendola, A. Assessing Lower Limb Alignment: Comparsion of Standard Knee Xray vs Long Leg View. Iowa Orthop. J. 2015, 35, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Niswander, W.; Wang, W.; Kontson, K. Optimization of IMU Sensor Placement for the Measurement of Lower Limb Joint Kinematics. Sensors 2020, 20, 5993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niswander, W.; Kontson, K. Evaluating the Impact of IMU Sensor Location and Walking Task on Accuracy of Gait Event Detection Algorithms. Sensors 2021, 21, 3989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwama, Y.; Harato, K.; Kobayashi, S.; Niki, Y.; Ogihara, N.; Matsumoto, M.; Nakamura, M.; Nagura, T. Estimation of the External Knee Adduction Moment during Gait Using an Inertial Measurement Unit in Patients with Knee Osteoarthritis. Sensors 2021, 21, 1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menz, H.B.; Lord, S.R. Acceleration Patterns of the Head and Pelvis When Walking Are Associated with Risk of Falling in Community-Dwelling Older People. J. Gerontol. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2003, 58, M446–M452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asuero, A.G.; Sayago, A.; González, A.G. The Correlation Coefficient: An Overview. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2006, 36, 41–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, S.; Li, M.; Jia, Y.; Gao, W.; Xu, J.; Zhang, B.; Guo, H.; Feng, A.; Sun, R. How Do the Morphological Abnormalities of Femoral Head and Neck, Femoral Shaft and Femoral Condyle Affect the Occurrence and Development of Medial Knee Osteoarthritis. Orthop. Surg. 2023, 15, 3174–3181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.C.; Gielis, W.P.; Van Egmond, N.; Weinans, H.; Slump, C.H.; Sakkers, R.J.B.; Custers, R.J.H. The Need for a Standardized Whole Leg Radiograph Guideline: The Effects of Knee Flexion, Leg Rotation, and X-Ray Beam Height. J. Cartil. Jt. Preserv. 2021, 1, 100022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, A.A.; Meehan, J.P.; Moroski, N.M.; Anderson, M.J.; Lamba, R.; Parise, C. Do Small Changes in Rotation Affect Measurements of Lower Extremity Limb Alignment? J. Orthop. Surg. 2017, 12, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micicoi, G.; Khakha, R.; Kley, K.; Wilson, A.; Cerciello, S.; Ollivier, M. Managing Intra-articular Deformity in High Tibial Osteotomy: A Narrative Review. J. Exp. Orthop. 2020, 7, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishii, Y.; Noguchi, H.; Matsuda, Y.; Kiga, H.; Takeda, M.; Toyabe, S. Preoperative Laxity in Osteoarthritis Patients Undergoing Total Knee Arthroplasty. Int. Orthop. 2009, 33, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozaki, T.; Fukui, D.; Yamamoto, E.; Nishiyama, D.; Yamanaka, M.; Murata, A.; Yamada, H. Medial Meniscus Extrusion and Varus Tilt of Joint Line Convergence Angle Increase Stress in the Medial Compartment of the Knee Joint in the Knee Extension Position-finite Element Analysis. J. Exp. Orthop. 2022, 9, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moyer, R.F.; Birmingham, T.B.; Chesworth, B.M.; Kean, C.O.; Giffin, J.R. Alignment, Body Mass and Their Interaction on Dynamic Knee Joint Load in Patients with Knee Osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2010, 18, 888–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mochizuki, T.; Koga, Y.; Tanifuji, O.; Sato, T.; Watanabe, S.; Koga, H.; Kobayashi, K.; Omori, G.; Endo, N. Effect on Inclined Medial Proximal Tibial Articulation for Varus Alignment in Advanced Knee Osteoarthritis. J. Exp. Orthop. 2019, 6, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, M.A.; Birmingham, T.B.; Bryant, D.; Jones, I.; Giffin, J.R.; Jenkyn, T.R.; Vandervoort, A.A. Lateral Trunk Lean Explains Variation in Dynamic Knee Joint Load in Patients with Medial Compartment Knee Osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2008, 16, 591–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, L. The Role of Proprioceptive Deficits, Ligamentous Laxity, and Malalignment in Development and Progression of Knee Osteoarthritis. J. Rheumatol. Suppl. 2004, 70, 87–92. [Google Scholar]

- MacFarlane, L.A.; Yang, H.; Collins, J.E.; Guermazi, A.; Jones, M.H.; Teeple, E.; Xu, L.; Losina, E.; Katz, J.N. Associations among Meniscal Damage, Meniscal Symptoms and Knee Pain Severity. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2017, 25, 850–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Age (years) | 63.5 | ± | 8.6 |

| Height (cm) | 154.8 | ± | 6.0 |

| Weight (kg) | 58.5 | ± | 9.7 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.3 | ± | 3.7 |

| Measured limb (right/left) | 7 | / | 12 |

| Kellgren–Lawrence grade (1/2/3/4) right knee | 0/1/4/2 | ||

| Kellgren–Lawrence grade (1/2/3/4) left knee | 2/5/4/1 | ||

| Measures | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Standing TA (°) | 7.9 | ± | 2.7 |

| Supine TA (°) | 6.1 | ± | 1.5 |

| ΔTA (°) | 1.8 | ± | 1.6 |

| FTA (°) | 179.6 | ± | 4.1 |

| JLCA (°) | 3.1 | ± | 3.0 |

| F-ΔVTA (m/s2) | 6.0 | ± | 3.2 |

| T-ΔVTA (m/s2) | 5.2 | ± | 4.1 |

| FTA | JLCA | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ρ | 95% CI for ρ | p-Value | ρ | 95% CI for ρ | p-Value | |

| Standing TA | 0.47 | 0.07, 0.76 | 0.04 | 0.80 | 0.29, 0.92 | <0.01 |

| Dependent Variables | Independent Variables | Unstandardized Coefficient | 95% CI for Β | Standardized Coefficient | 95% CI for β | p-Value | RMSE | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Β | (Lower Limit, Upper Limit) | β | (Lower Limit, Upper Limit) | |||||

| F-ΔVTA (m/s2) | ||||||||

| Intercept | 3.49 | 1.72, 5.26 | 0.87, 2.72 | |||||

| ΔTA (°) | 1.37 | 0.65, 2.10 | 0.70 | 0.33, 1.07 | <0.01 * | 2.28 | 0.48 | |

| T-ΔVTA (m/s2) | ||||||||

| Intercept | 2.09 | −0.26, 4.43 | −0.10, 1.76 | |||||

| ΔTA (°) | 1.68 | 0.72, 2.64 | 0.67 | 0.29, 1.05 | <0.01 * | 3.02 | 0.46 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Karashima, R.; Kishimoto, S.; Ibara, T.; Hada, K.; Motoyama, T.; Kawashima, M.; Murofushi, Y.; Katoh, H. Effects of Weight-Bearing-Induced Changes in Tibial Inclination Angle on Varus Thrust During Gait in Female Patients with Knee Osteoarthritis. Biomechanics 2025, 5, 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomechanics5040098

Karashima R, Kishimoto S, Ibara T, Hada K, Motoyama T, Kawashima M, Murofushi Y, Katoh H. Effects of Weight-Bearing-Induced Changes in Tibial Inclination Angle on Varus Thrust During Gait in Female Patients with Knee Osteoarthritis. Biomechanics. 2025; 5(4):98. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomechanics5040098

Chicago/Turabian StyleKarashima, Ryosuke, Shintaro Kishimoto, Takuya Ibara, Kiyotaka Hada, Tatsuo Motoyama, Masayuki Kawashima, Yusuke Murofushi, and Hiroshi Katoh. 2025. "Effects of Weight-Bearing-Induced Changes in Tibial Inclination Angle on Varus Thrust During Gait in Female Patients with Knee Osteoarthritis" Biomechanics 5, no. 4: 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomechanics5040098

APA StyleKarashima, R., Kishimoto, S., Ibara, T., Hada, K., Motoyama, T., Kawashima, M., Murofushi, Y., & Katoh, H. (2025). Effects of Weight-Bearing-Induced Changes in Tibial Inclination Angle on Varus Thrust During Gait in Female Patients with Knee Osteoarthritis. Biomechanics, 5(4), 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomechanics5040098