Influence of Coronary Flow and Left Ventricular Outflow Tract Velocity on LDL Accumulation and Calcification in Aortic Valve Leaflets

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. CFD Methodology

2.1.1. Fluid Flow Solver

2.1.2. Structural Analysis Solver

2.1.3. Fluid–Structure Interaction

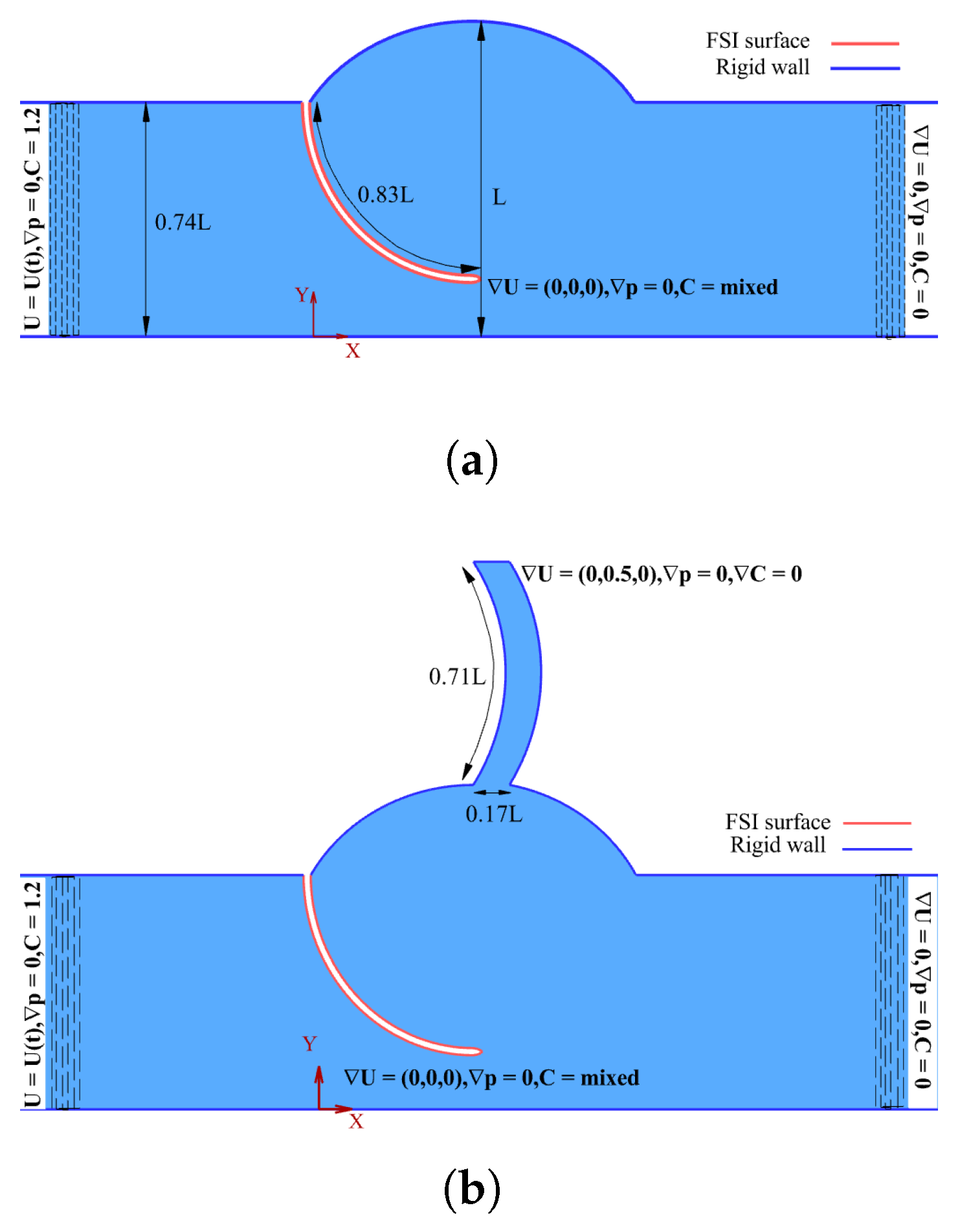

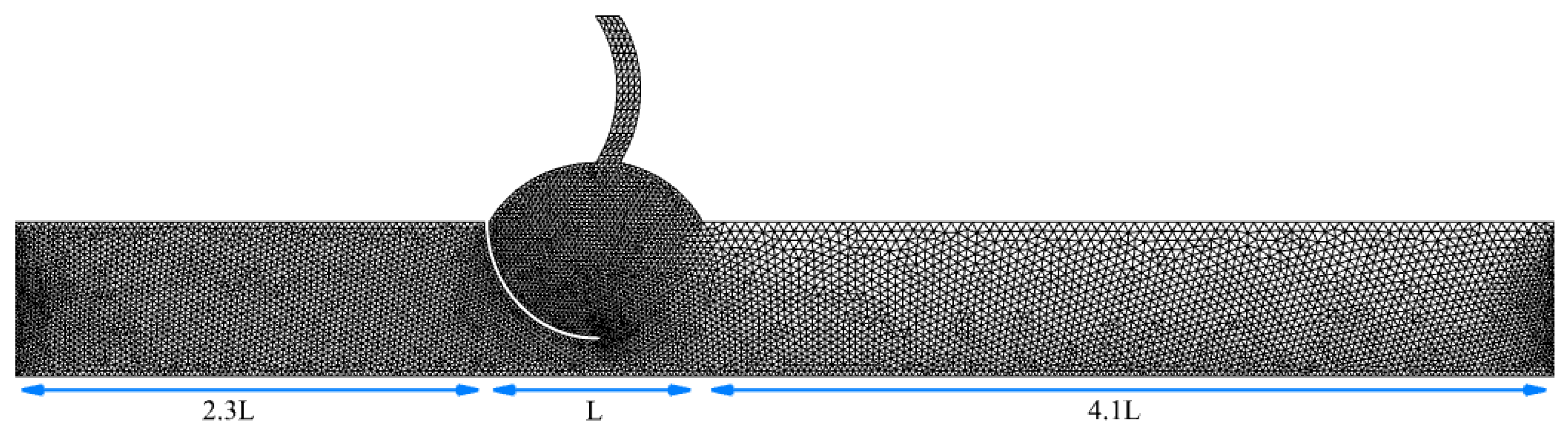

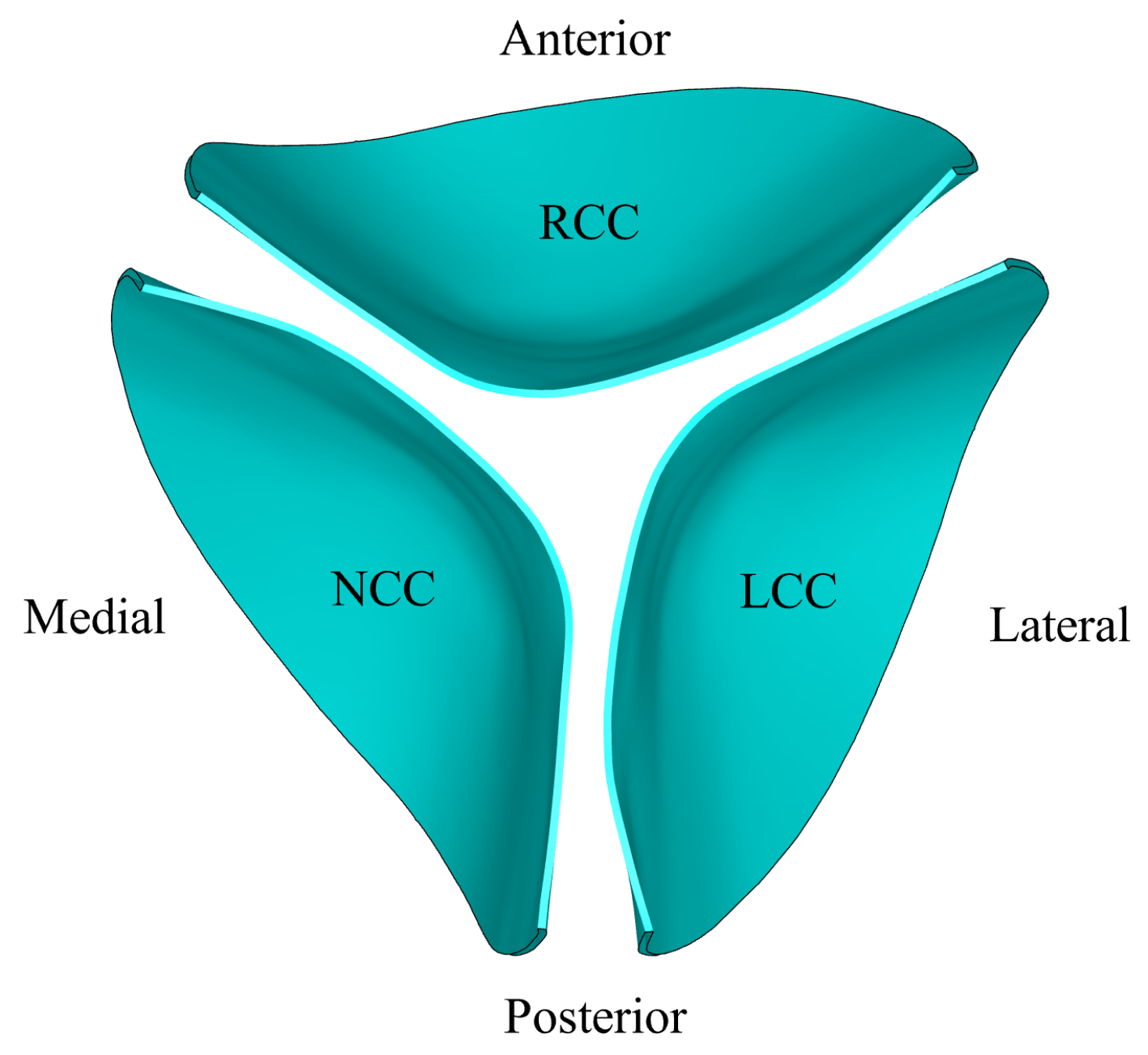

2.2. Geometry and Grid

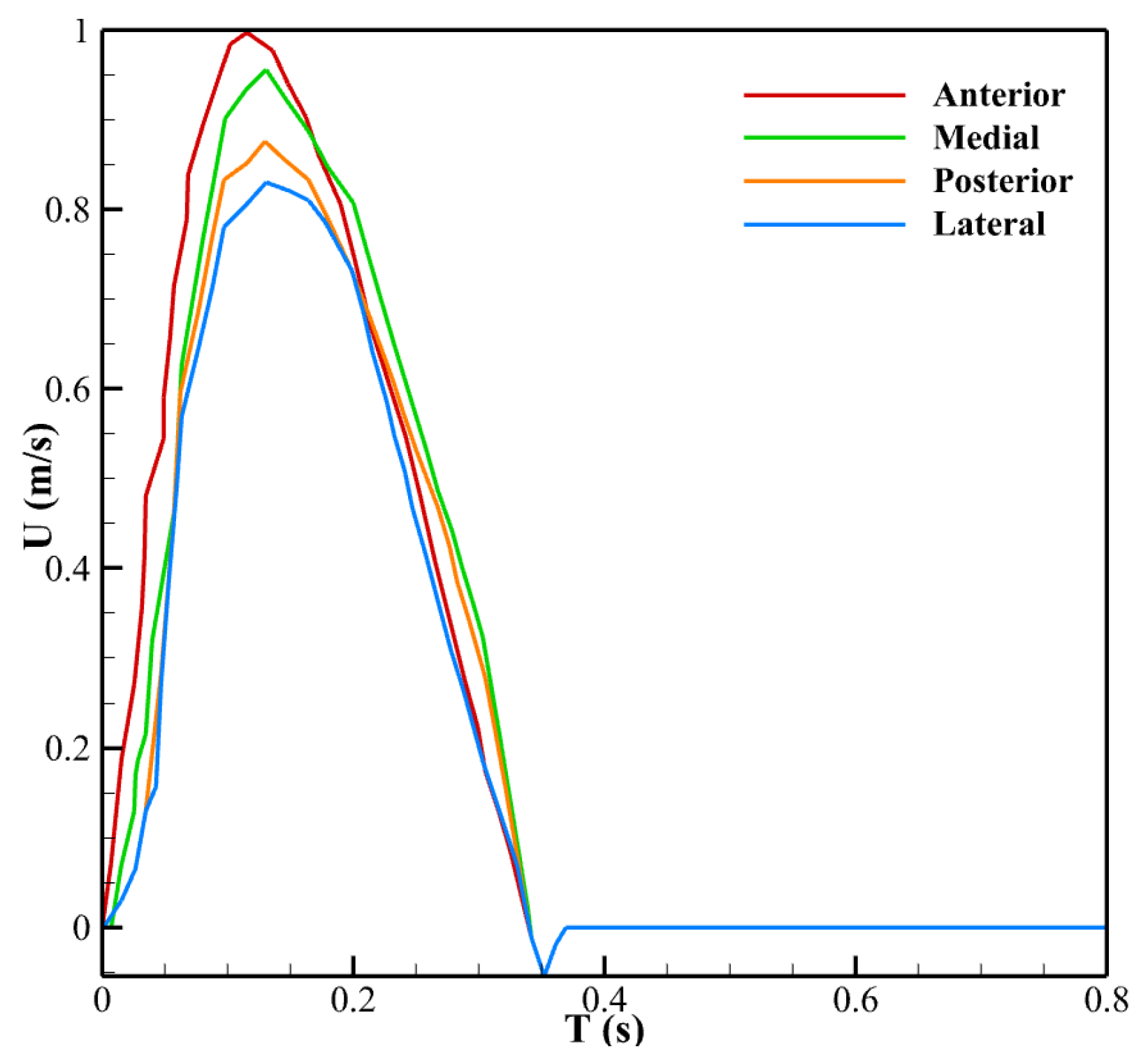

2.3. Boundary Conditions

3. Results

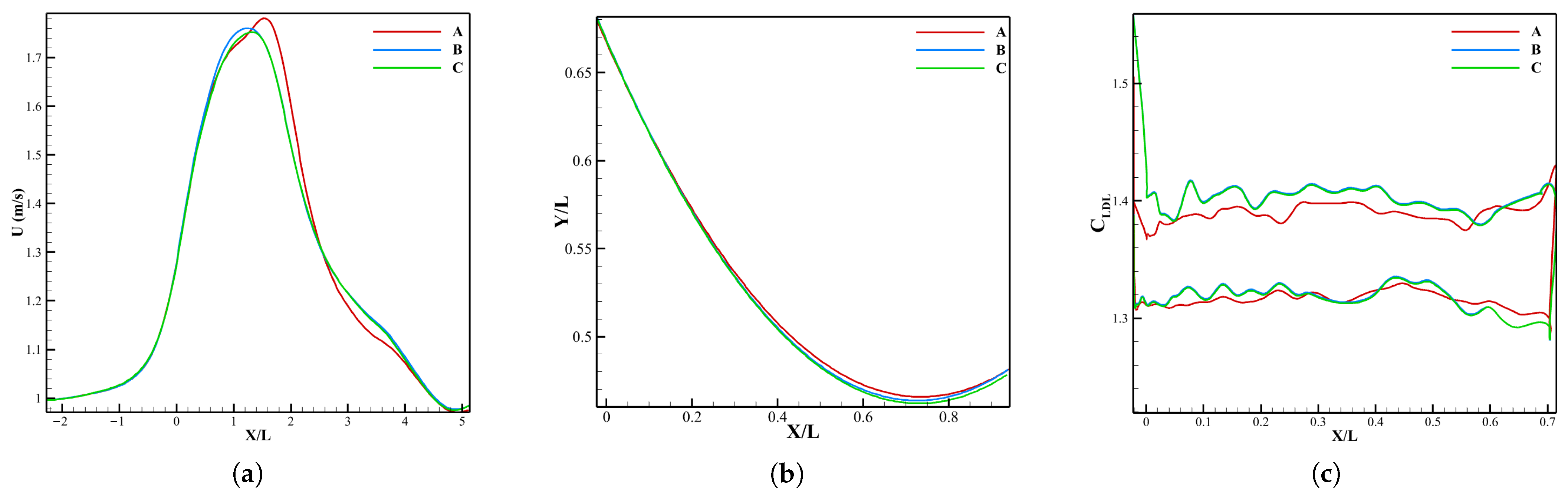

3.1. Verification

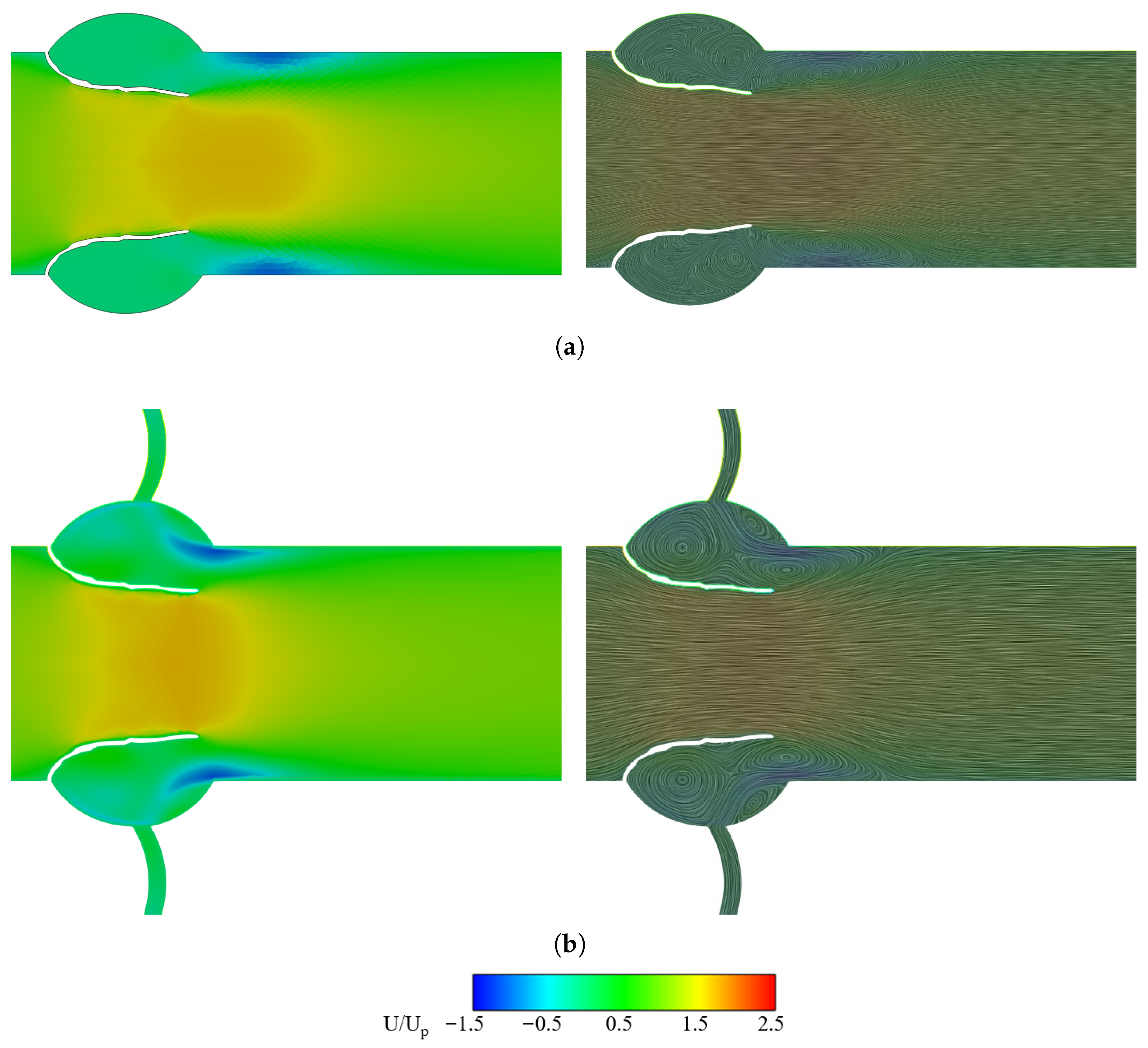

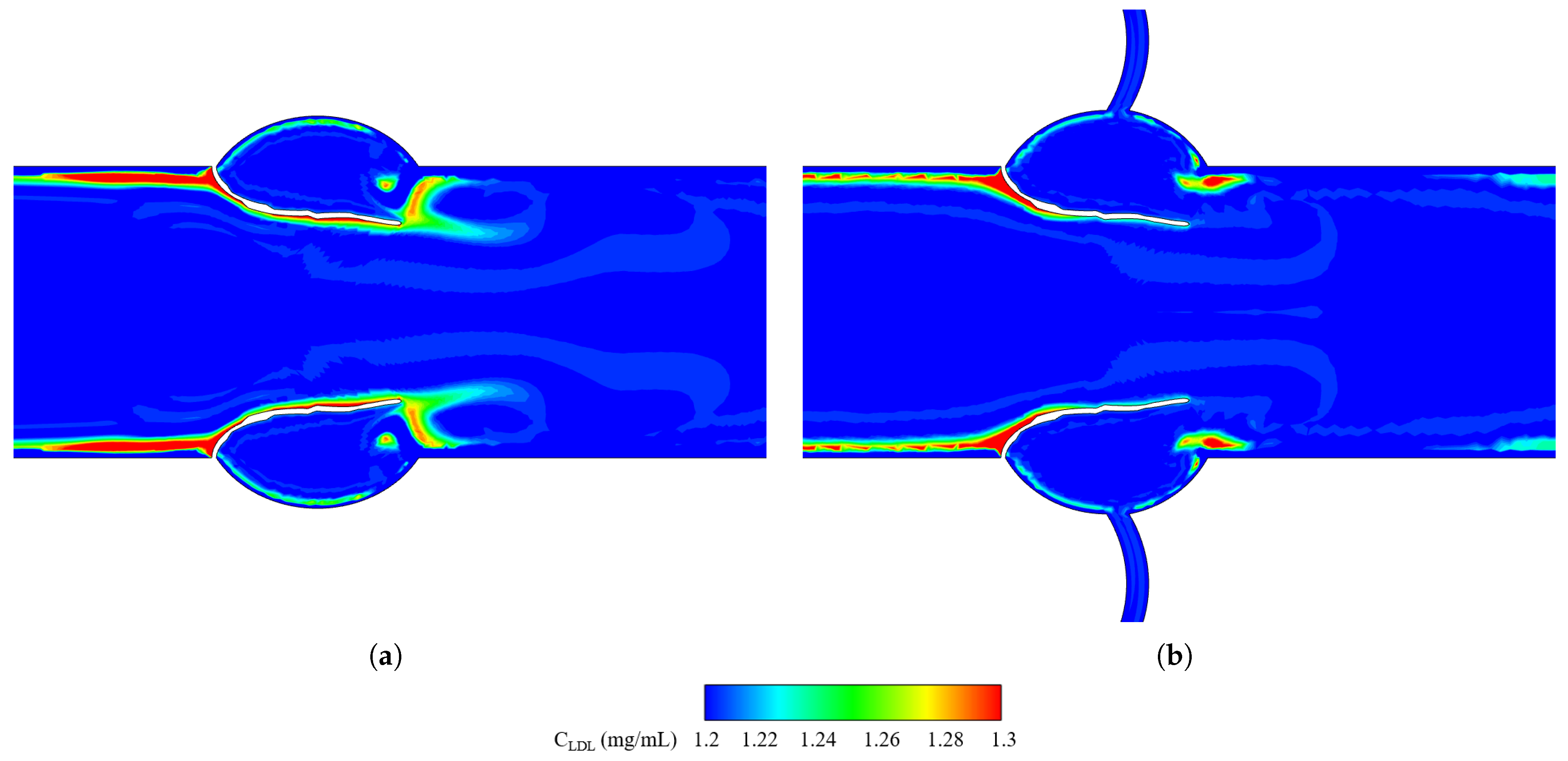

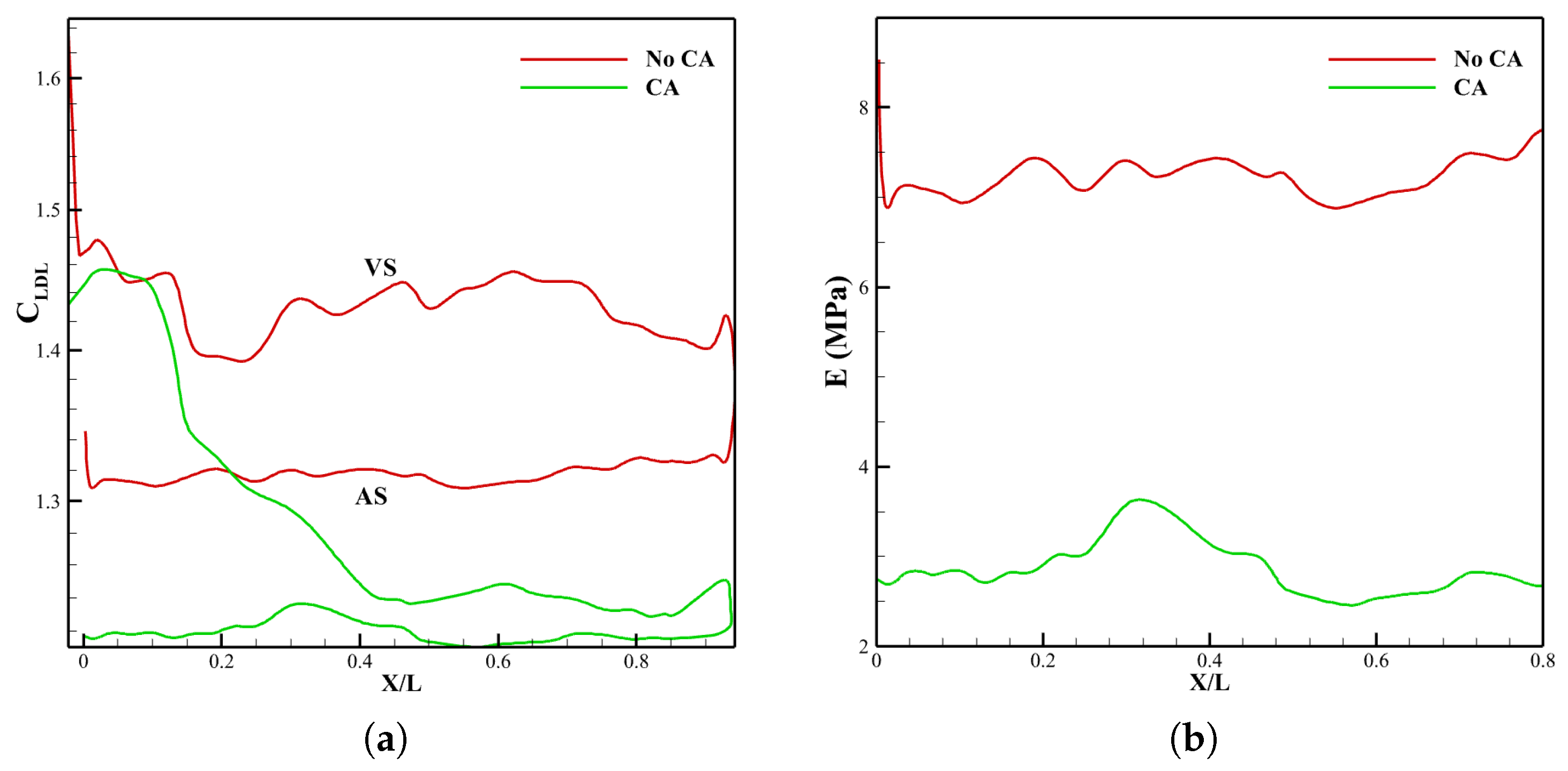

3.2. Effect of Coronary Artery on LDL Distribution of Aortic Valve Leaflets

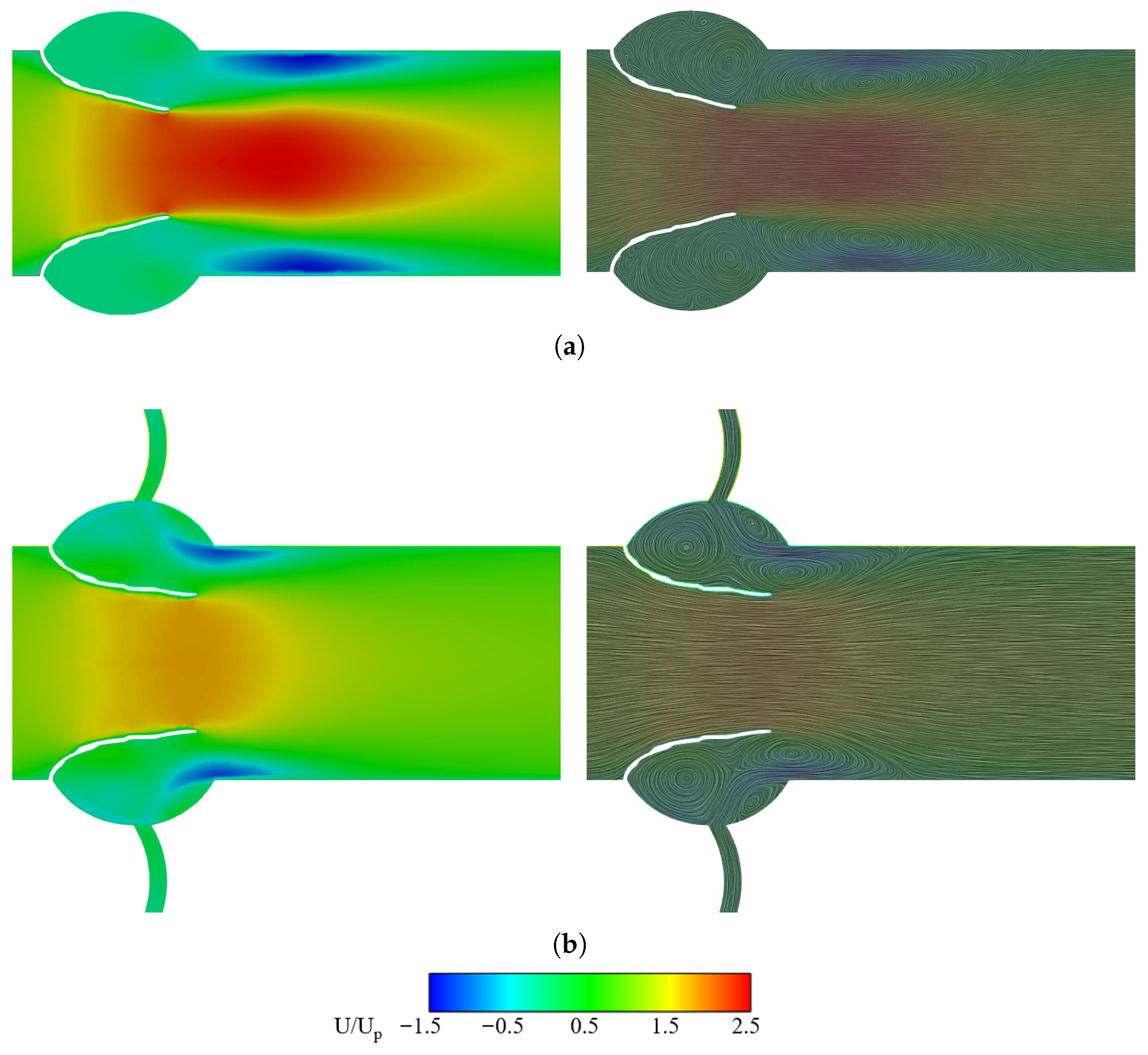

3.2.1. Velocity Field and LDL Distribution

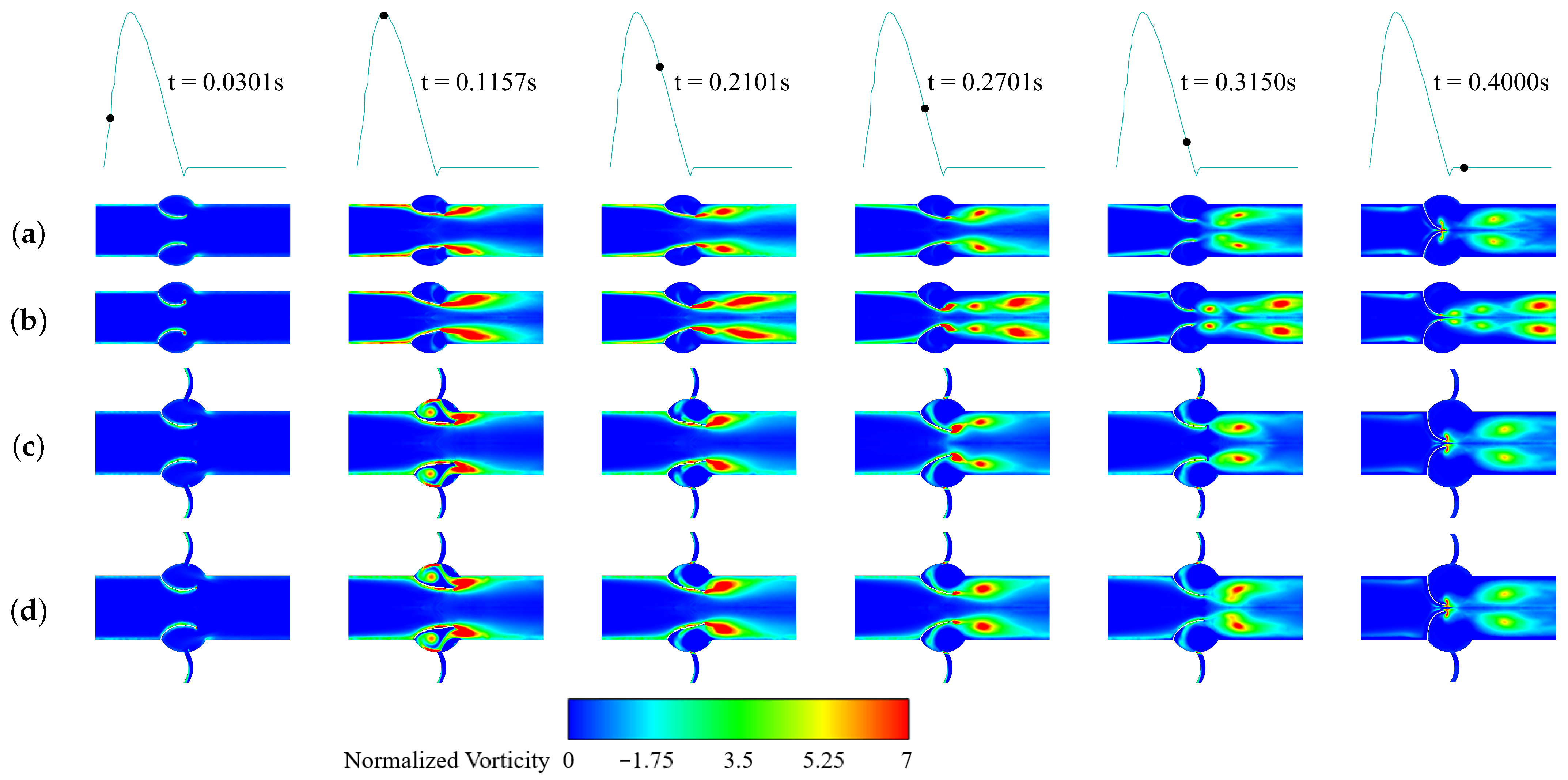

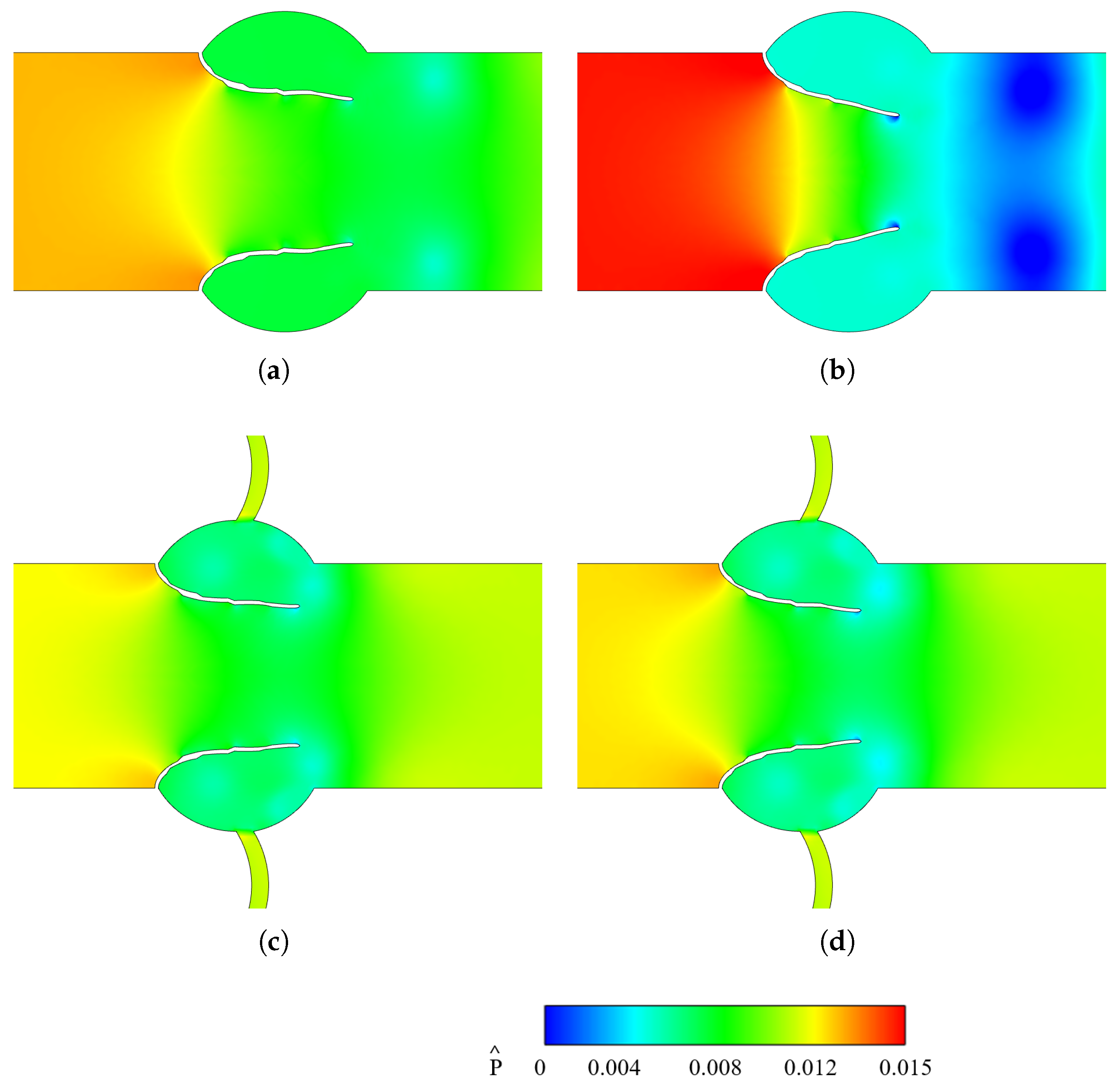

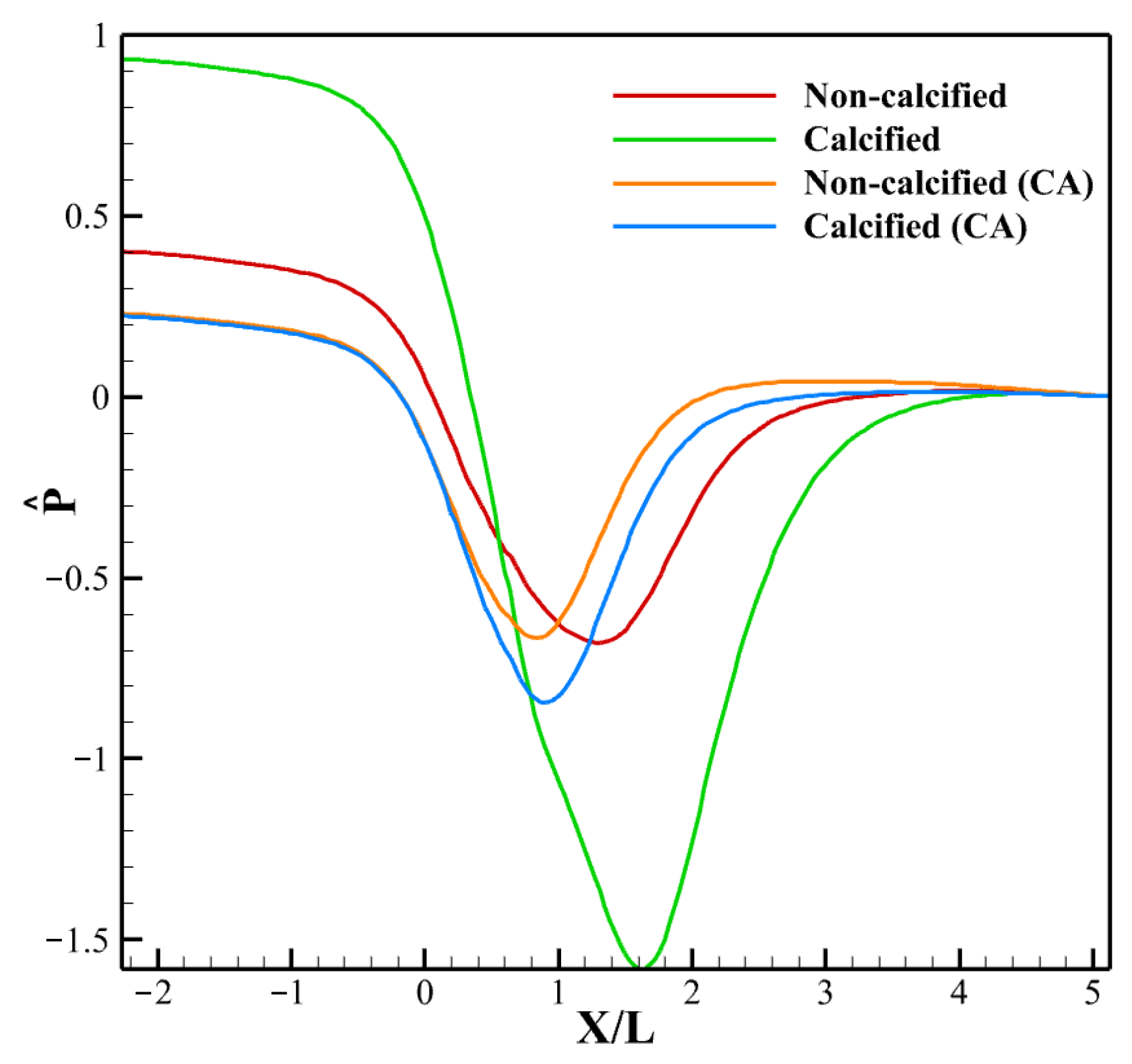

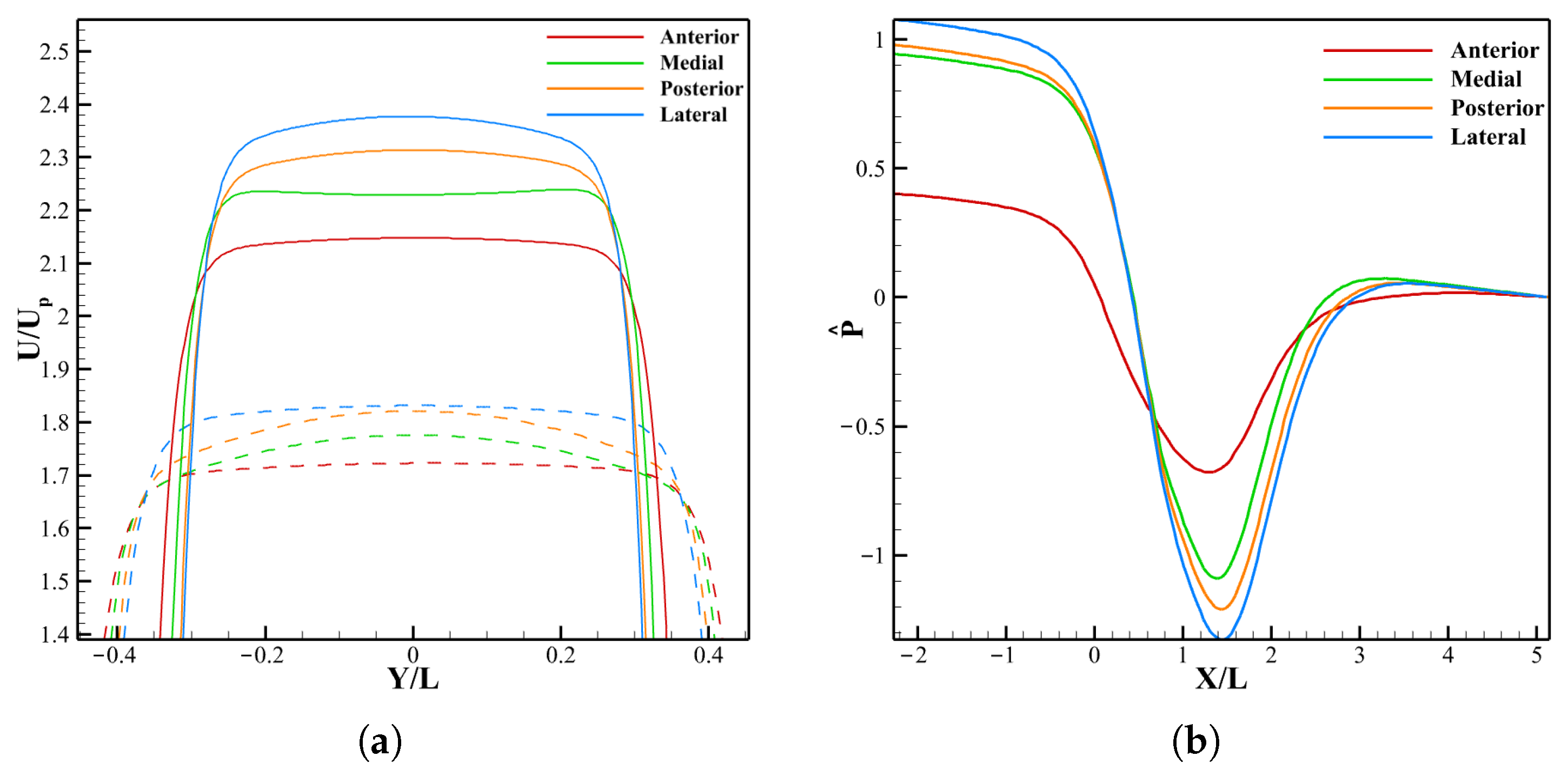

3.2.2. Vorticity and Pressure

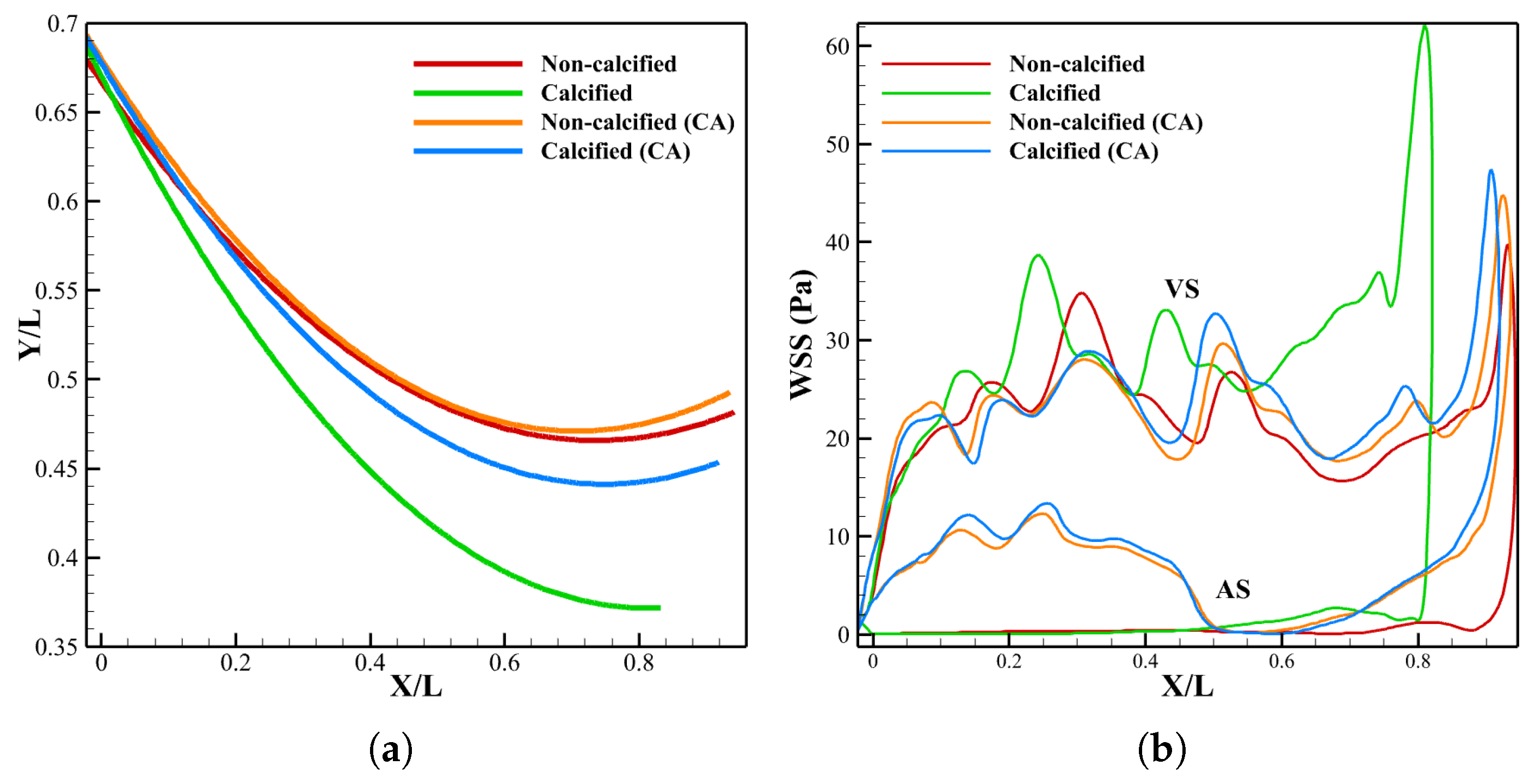

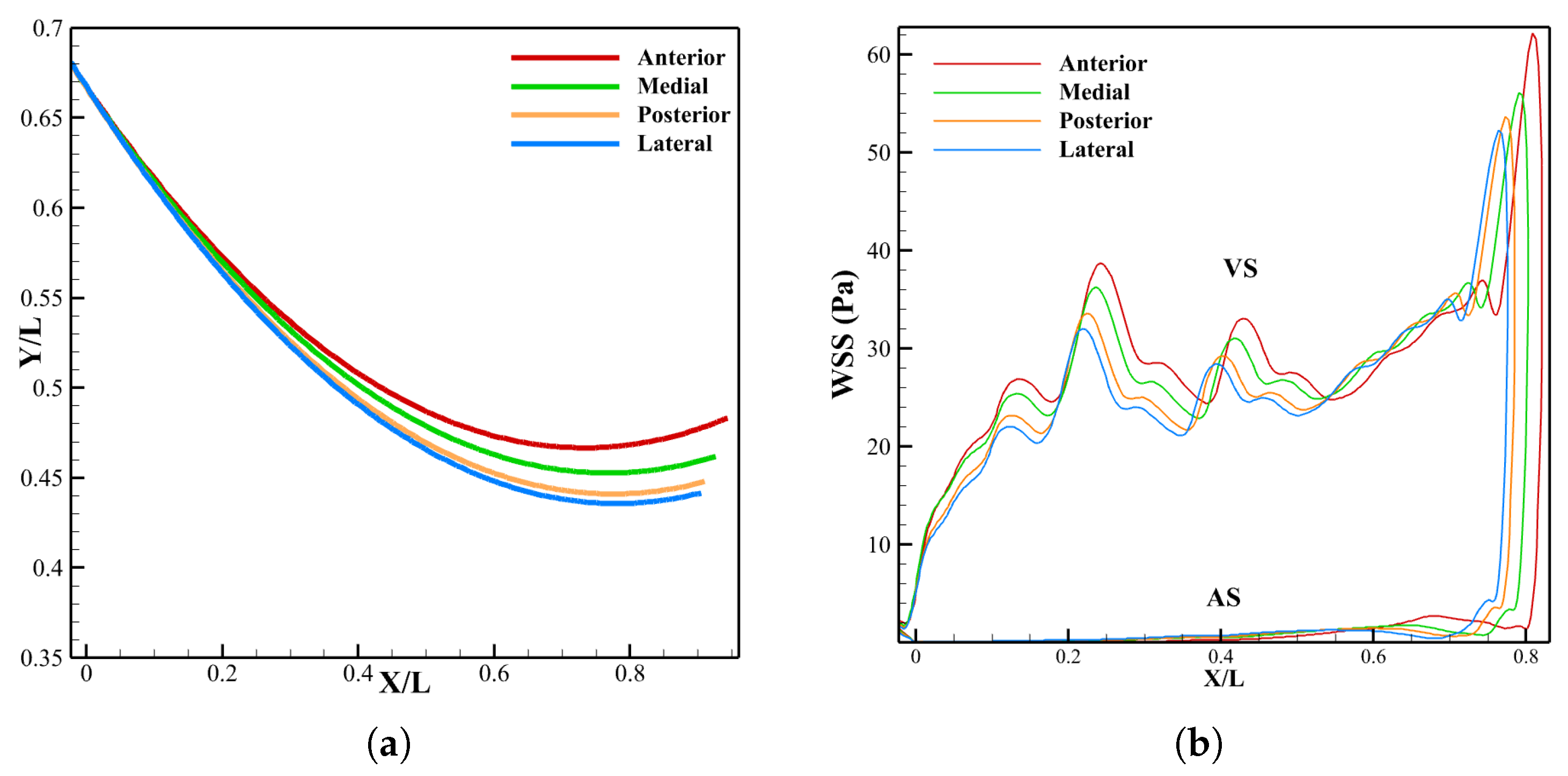

3.2.3. Leaflet Profile and WSS

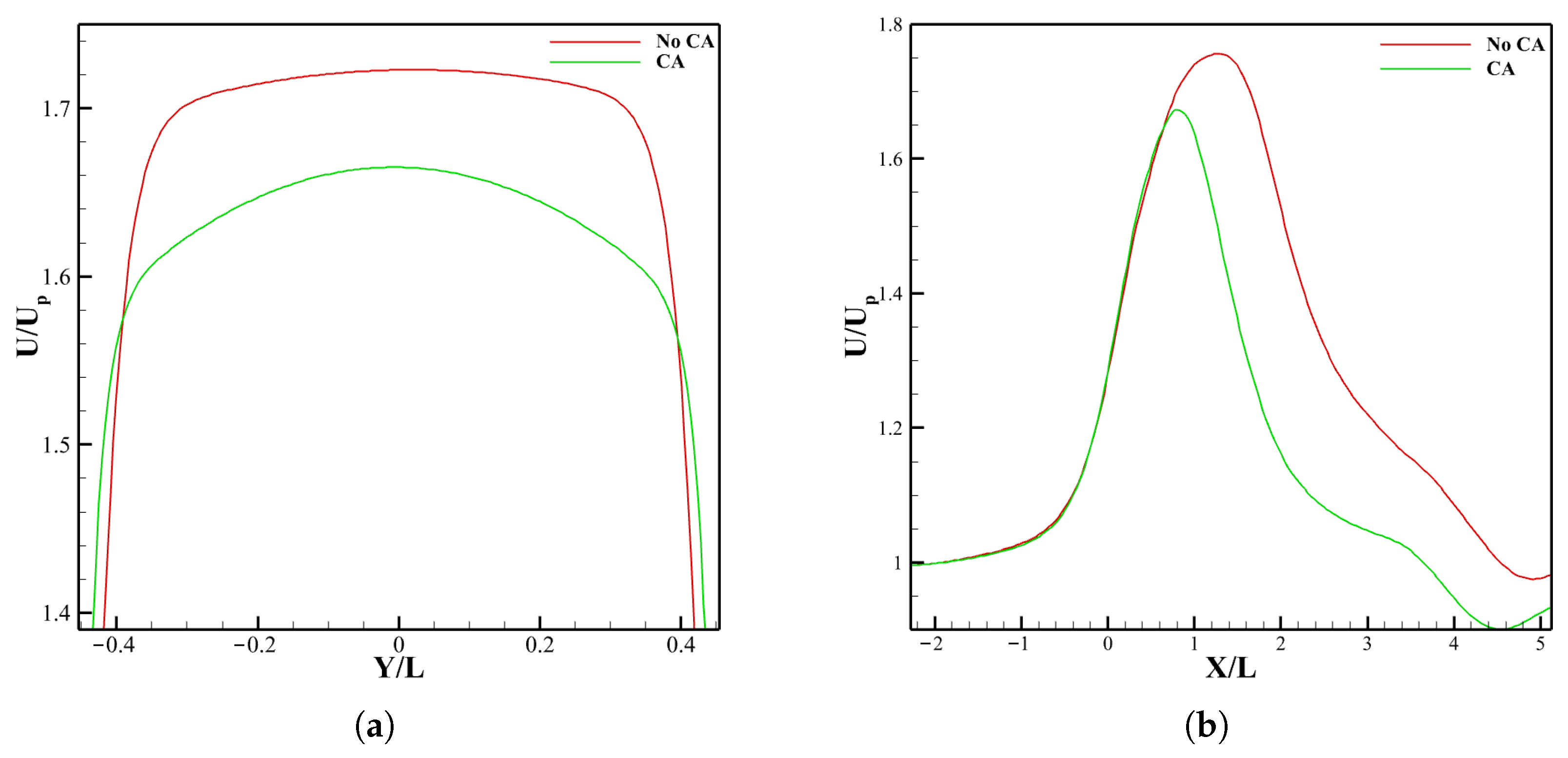

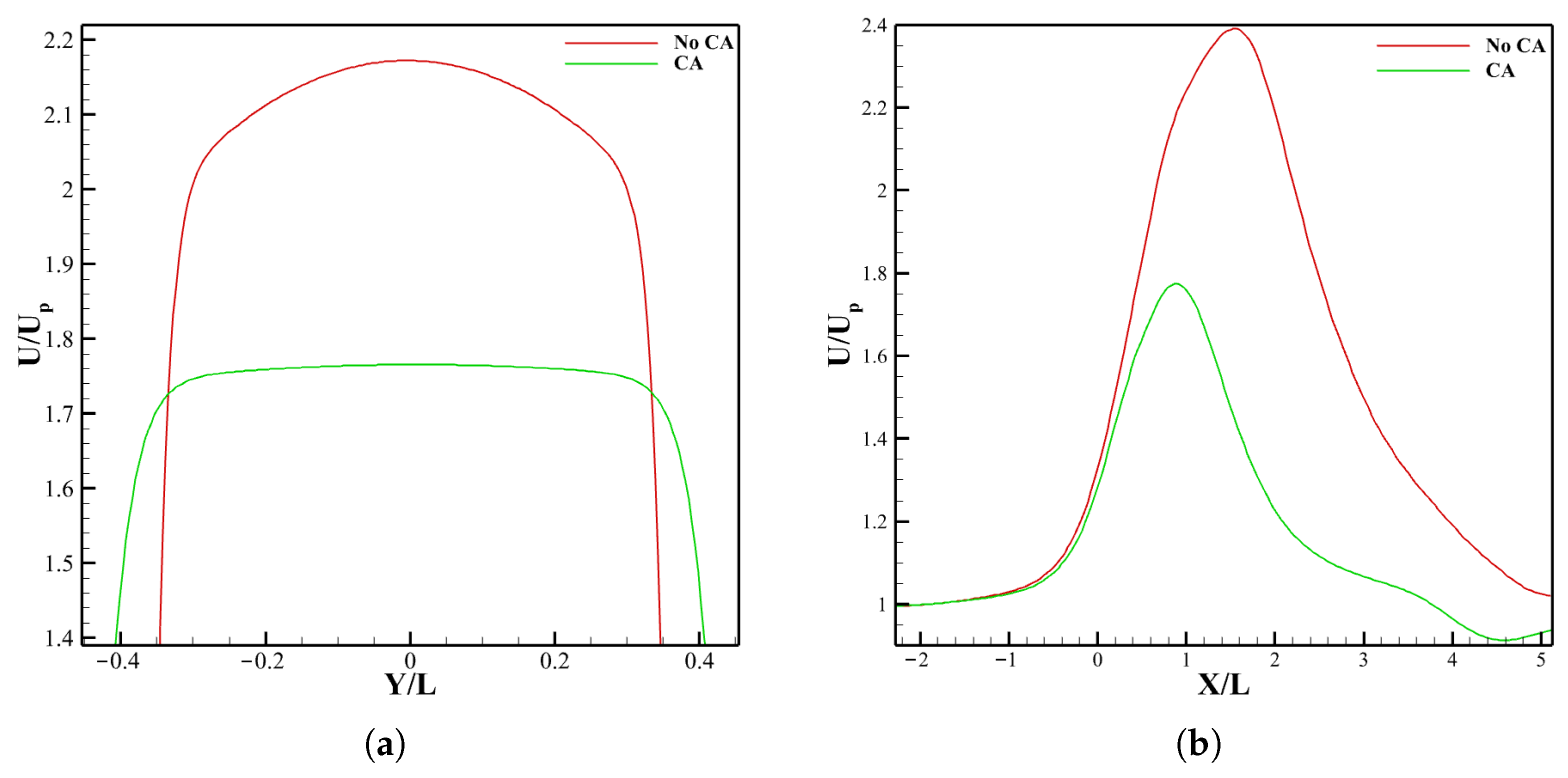

3.3. Effect of LVOT Velocity Variation on LDL Distribution

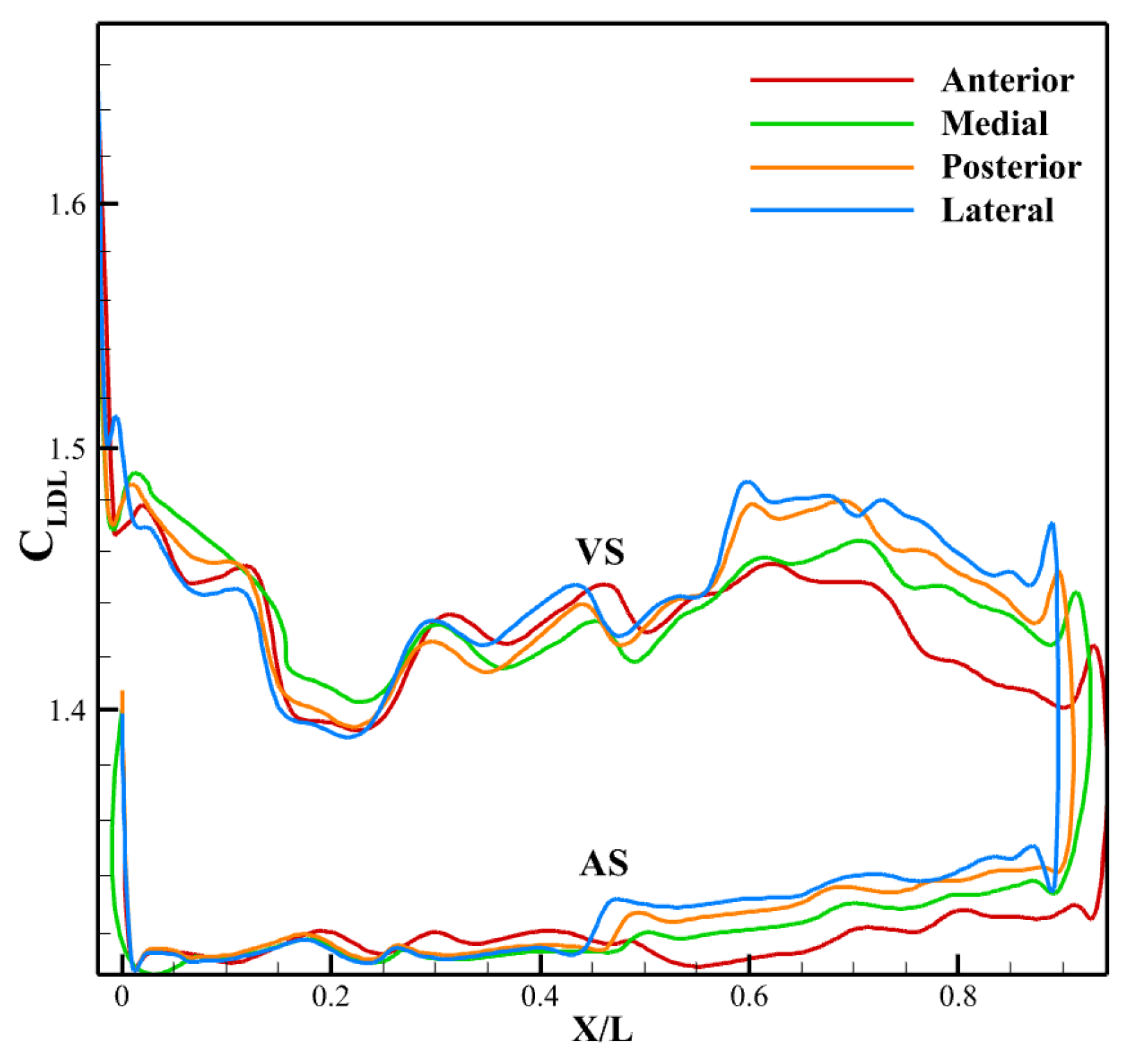

3.3.1. LDL Distribution, Velocity and Pressure

3.3.2. Leaflet Profile and WSS

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CAVD | Calcific aortic valve disease |

| LCC | Left coronary cusp |

| RCC | Right coronary cusp |

| NCC | Non-coronary cusp |

| LVOT | Left ventricular outflow tract |

| LDL | Low-density lipoprotein |

| CA | Coronary artery |

References

- Hsieh, G.; Berman, A.N.; Biery, D.W.; Rizk, T.; Blankstein, R. The Current Landscape of Lipoprotein(a) in Calcific Aortic Valvular Disease. Curr. Opin. Cardiol. 2021, 36, 542–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, W.; Wang, Z.; Sun, C.; Zhang, D.M. Pathogenesis and Molecular Immune Mechanism of Calcified Aortic Valve Disease. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 765419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, S.S.; Aday, A.W.; Almarzooq, Z.I.; Anderson, C.A.; Arora, P.; Avery, C.L.; Baker-Smith, C.M.; Gibbs, B.B.; Beaton, A.Z.; Boehme, A.K.; et al. 2024 Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics: A Report of US and Global Data from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2024, 149, E347–E913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, L.; Hao, Y.; Ma, P.; Zhu, G.; Luo, X.; Gao, H. Fluid-structure interaction simulation of calcified aortic valve stenosis. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2022, 19, 13172–13192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, Y. 2D Fluid-Structure Model of Aortic Valve Using a Derived Muscular Model Equation. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Bio Signals, Images, and Instrumentation (ICBSII), Chennai, India, 16–17 March 2023; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amindari, A.; Saltik, L.; Kirkkopru, K.; Yacoub, M.; Yalcin, H.C. Assessment of calcified aortic valve leaflet deformations and blood flow dynamics using fluid-structure interaction modeling. Inform. Med. Unlocked 2017, 9, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, M.; Divo, E.; Adamczyk, W.P. Fluid–Structure Interaction methods for the progressive anatomical and artificial aortic valve stenosis. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2022, 227, 107410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivi, A.R.; Sedaghatizadeh, N.; Cazzolato, B.S.; Zander, A.C.; Nelson, A.J.; Roberts-Thomson, R.; Yoganathan, A.; Arjomandi, M. Hemodynamics of a stenosed aortic valve: Effects of the geometry of the sinuses and the positions of the coronary ostia. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2020, 188, 106015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivi, A.R.; Sedaghatizadeh, N.; Cazzolato, B.S.; Zander, A.C.; Roberts-Thomson, R.; Nelson, A.J.; Arjomandi, M. Fluid structure interaction modelling of aortic valve stenosis: Effects of valve calcification on coronary artery flow and aortic root hemodynamics. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2020, 196, 105647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oks, D.; Samaniego, C.; Houzeaux, G.; Butakoff, C.; Vázquez, M. Fluid–structure interaction analysis of eccentricity and leaflet rigidity on thrombosis biomarkers in bioprosthetic aortic valve replacements. Int. J. Numer. Methods Biomed. Eng. 2022, 38, e3649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza-Taimuri, M.; Chen, I.Y.; Sadat, H. Hemodynamic Analysis of Non-Uniformly Calcified Aortic Valve Using a Partitioned Fluid-Structure Interaction Framework. Cardiovasc. Eng. Technol. 2025; accepted. [Google Scholar]

- Amindari, A.; Kirkkopru, K.; Saltik, L.; Sunbuloglu, E. Effect of non-linear leaflet material properties on aortic valve dynamics—A coupled fluid-structure approach. Eng. Solid Mech. 2021, 9, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, R.; Han, X.; Xiong, T.; Chen, M.; Williams, J.; Lin, P. Numerical investigation of calcification effects on aortic valve motions and ambient flow characteristics. J. Fluids Struct. 2024, 124, 104014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, I.Y.; Vedula, V.; Malik, S.B.; Liang, T.; Chang, A.Y.; Chung, K.S.; Sayed, N.; Tsao, P.S.; Giacomini, J.C.; Marsden, A.L.; et al. Preoperative Computed Tomography Angiography Reveals Leaflet-Specific Calcification and Excursion Patterns in Aortic Stenosis. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2021, 14, 1122–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kupari, M.; Hekali, P.; Poutanen, V.P. Cross sectional profiles of systolic flow velocities in left ventricular outflow tract of normal subjects. Heart 1995, 74, 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gollmann-Tepeköylü, C.; Nägele, F.; Engler, C.; Stoessel, L.; Zellmer, B.; Graber, M.; Hirsch, J.; Pölzl, L.; Ruttmann, E.; Tancevski, I.; et al. Different calcification patterns of tricuspid and bicuspid aortic valves and their clinical impact. Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2022, 35, ivac274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanchaitanawong, W.; Kanjanavanit, R.; Srisuwan, T.; Chootipongchaivat, S.; Laksanabunsong, P. Diagnostic role of aortic valve calcium scoring in various etiologies of aortic stenosis. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 8019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Salaun, E.; Côté, N.; Wu, Y.; Mahjoub, H.; Mathieu, P.; Dahou, A.; Zenses, A.S.; Clisson, M.; Pibarot, P.; et al. Association of Bioprosthetic Aortic Valve Leaflet Calcification on Hemodynamic and Clinical Outcomes. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 76, 1737–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demer, L.L.; Tintut, Y. Vascular calcification: Pathobiology of a multifaceted disease. Circulation 2008, 117, 2938–2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsimikas, S.; Karwatowska-Prokopczuk, E.; Gouni-Berthold, I.; Tardif, J.C.; Baum, S.J.; Steinhagen-Thiessen, E.; Shapiro, M.D.; Stroes, E.S.; Moriarty, P.M.; Nordestgaard, B.G.; et al. Lipoprotein(a) Reduction in Persons with Cardiovascular Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lerman, D.A.; Prasad, S.; Alotti, N. Calcific Aortic Valve Disease: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Approaches. Eur. Cardiol. Rev. 2015, 10, 108–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The OpenFOAM Foundation. OpenFOAM: The Open Source CFD Toolbox, Version 11; The OpenFOAM Foundation: London, UK, 2024.

- Dhondt, G. CalculiX: A Free Software Three-Dimensional Structural Finite Element Program, Version 2.21; MTU Aero Engines: Munich, Germany, 2024.

- Bungartz, H.J.; Lindner, F.; Gatzhammer, B.; Mehl, M.; Scheufele, K.; Shukaev, A.; Uekermann, B. preCICE—A Fully Parallel Library for Multi-Physics Surface Coupling. Comput. Fluids 2016, 141, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Merkle, C.; Abdallah, S.; Tarbell, J. Numerical simulation of unsteady laminar flow through a tilting disk heart valve: Prediction of vortex shedding. J. Biomech. 1994, 27, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arminio, M.; Carbonaro, D.; Morbiducci, U.; Gallo, D.; Chiastra, C. Fluid-structure interaction simulation of mechanical aortic valves: A narrative review exploring its role in total product life cycle. Front. Med. Technol. 2024, 6, 1399729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos, F.; Matijašević, D.; Terze, Z.; Oudheusden, B.; Bijl, H. OpenFOAM mesh motion using Radial Basis Function interpolation. In Proceedings of the 5th European Congress on Computational Methods in Applied Sciences and Engineering (ECCOMAS 2008), Venice, Italy, 30 June–5 July 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, W.; Martin, C.; Pham, T. Computational modeling of cardiac valve function and intervention. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2014, 16, 53–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cataloglu, A.; Gould, P.; Clark, R. Validation of a simplified mathematical model for the stress analysis of human aortic heart valves. J. Biomech. 1975, 8, 347–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, T. Fluid-Structure Interactions: Models, Analysis and Finite Elements; Lecture Notes in Computational Science and Engineering; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; Volume 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badia, S.; Quaini, A.; Quarteroni, A. Splitting Methods Based on Algebraic Factorization for Fluid-Structure Interaction. SIAM J. Sci. Comput. 2008, 30, 1778–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazilevs, Y.; Calo, V.M.; Hughes, T.J.; Zhang, Y. Isogeometric Fluid-Structure Interaction: Theory, Algorithms, and Computations. Comput. Mech. 2008, 43, 3–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geuzaine, C.; Remacle, J.F. Gmsh: A 3-D finite element mesh generator with built-in pre- and post-processing facilities. Int. J. Numer. Methods Eng. 2009, 79, 1309–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halevi, R.; Hamdan, A.; Marom, G.; Mega, M.; Raanani, E.; Haj-Ali, R. Progressive aortic valve calcification: Three-dimensional visualization and biomechanical analysis. J. Biomech. 2015, 48, 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, F.B.; Dai, H.; Luo, H.; Doyle, F.J.; Rousseau, B. Fluid-structure interaction involving large deformations: 3D simulations and applications to biological systems. J. Comput. Phys. 2014, 258, 451–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jughiman, M.K.; Al-Omair, M.A. Modelling coronary flow after the Norwood operation: Influence of a suggested novel technique for coronary transfer. Glob. Cardiol. Sci. Pract. 2018, 2018, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Suárez, A.; Pérez, J.J.; O’Brien, B.; Elahi, A. In Silico Modelling to Assess the Electrical and Thermal Disturbance Provoked by a Metal Intracoronary Stent during Epicardial Pulsed Electric Field Ablation. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2022, 9, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flemister, D.C.; Hatoum, H.; Guhan, V.; Zebhi, B.; Lincoln, J.; Crestanello, J.; Dasi, L.P. Effect of Left and Right Coronary Flow Waveforms on Aortic Sinus Hemodynamics and Leaflet Shear Stress: Correlation with Calcification Locations. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2020, 48, 2796–2808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kolandavel, M.K.; Fruend, E.T.; Ringgaard, S.; Walker, P.G. The effects of time varying curvature on species transport in coronary arteries. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2006, 34, 1820–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obaid, D.; Molina, J.; Ademiloye, A. A New Open-source Solver for Early Detection of Atherosclerosis Based On Hemodynamics and LDL Transport Simulation. Eng. Rep. 2024, 6, e12955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadrabadi, M.S.; Hedayat, M.; Borazjani, I.; Arzani, A. Fluid-structure coupled biotransport processes in aortic valve disease. J. Biomech. 2021, 117, 110239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butcher, J.T.; Nerem, R.M. Valvular endothelial cells and the mechanoregulation of valvular pathology. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2007, 362, 1445–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.; Vafai, K. Modeling of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) transport in the artery—Effects of hypertension. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2006, 49, 850–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soulis, J.V.; Giannoglou, G.D.; Dimitrakopoulou, M.; Papaioannou, V.; Logothetides, S.; Mikhailidis, D.P. Low-density lipoprotein concentration in the normal left coronary artery tree. Clin. Hemorheol. Microcirc. 2008, 39, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdani, S.K.; Ku, D.N. Oscillating LDL accumulation in normal human aortic arch. Biorheology 2010, 47, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nematollahi, A.; Shirani, E.; Mirzaee, I.; Sadeghi, M. Numerical simulation of LDL particles mass transport in human carotid artery under steady state conditions. Sci. Iran. 2012, 19, 519–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pletcher, M.J.; Bibbins-Domingo, K.; Liu, K.; Sidney, S.; Lin, F.; Vittinghoff, E.; Hulley, S.B. Nonoptimal lipids commonly present in young adults and coronary calcium later in life: The CARDIA (Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults) study. Ann. Intern. Med. 2010, 153, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, E.J.; Mack, P.J.; Schoen, F.J.; García-Cardeña, G.; Mofrad, M.R.K. Hemodynamic Environments from Opposing Sides of Human Aortic Valve Leaflets Evoke Distinct Endothelial Phenotypes In Vitro. Cardiovasc. Eng. 2010, 10, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yip, C.Y.Y.; Simmons, C.A. The aortic valve microenvironment and its role in calcific aortic valve disease. Cardiovasc. Pathol. 2011, 20, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, P.E.; Weinberg, P.D. Flow-dependent concentration polarization and the endothelial glycocalyx layer: Multi-scale aspects of arterial mass transport and their implications for atherosclerosis. Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol. 2014, 13, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soulis, J.; Giannoglou, G.; Dimitrakopoulou, M.; Papaioannou, V.; Logothetides, S.; Mikhailidis, D. Influence of oscillating flow on LDL transport and wall shear stress in the normal aortic arch. Open Cardiovasc. Med. J. 2009, 3, 128–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, H.; Kim, G.B.; Kweon, J.; Lee, S.J.; Kim, Y.; Kim, N.; Yang, D.H. The influence of the aortic valve angle on the hemodynamic features of the thoracic aorta. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 32316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, K.; Sucosky, P. Aortic valve leaflet wall shear stress characterization revisited: Impact of coronary flow. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Eng. 2016, 20, 468–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, H.; Akiyama, K.; Itatani, K.; DeRoo, S.; Sanchez, J.; Ferrari, G.; Colombo, P.C.; Takeda, K.; Wu, I.Y.; Kainuma, A.; et al. A novel in vivo assessment of fluid dynamics on aortic valve leaflet and its relationship with leaflet thickening. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 12345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, C.H.; Saikrishnan, N.; Tamilselvan, G.; Ajit, P. Experimental measurement of dynamic fluid shear stress on the aortic surface of the aortic valve leaflet. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2011, 39, 799–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosakis, G.; Gharib, M. The Influence of Valve Leaflet Stiffness Variability on Aortic Wall Shear Stress and LDL Deposition. J. Biomech. 2022, 120, 110357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veulemans, V.; Piayda, K.; Maier, O.; Bosbach, G.; Polzin, A.; Hellhammer, K.; Afzal, S.; Klein, K.; Dannenberg, L.; Zako, S.; et al. Aortic valve calcification is subject to aortic stenosis severity and the underlying flow pattern. Heart Vessel. 2021, 36, 242–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.L.; Chang, H.H.; Huang, P.J.; Wang, W.C.; Lin, S.Y. Different Calcification Stage in Each Cusp of a Calcified Tricuspid Aortic Valve. Circ. J. 2017, 81, 1953–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Raza-Taimuri, M.; Chen, I.Y.; Sadat, H. Influence of Coronary Flow and Left Ventricular Outflow Tract Velocity on LDL Accumulation and Calcification in Aortic Valve Leaflets. Biomechanics 2025, 5, 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomechanics5040099

Raza-Taimuri M, Chen IY, Sadat H. Influence of Coronary Flow and Left Ventricular Outflow Tract Velocity on LDL Accumulation and Calcification in Aortic Valve Leaflets. Biomechanics. 2025; 5(4):99. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomechanics5040099

Chicago/Turabian StyleRaza-Taimuri, Mishal, Ian Y. Chen, and Hamid Sadat. 2025. "Influence of Coronary Flow and Left Ventricular Outflow Tract Velocity on LDL Accumulation and Calcification in Aortic Valve Leaflets" Biomechanics 5, no. 4: 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomechanics5040099

APA StyleRaza-Taimuri, M., Chen, I. Y., & Sadat, H. (2025). Influence of Coronary Flow and Left Ventricular Outflow Tract Velocity on LDL Accumulation and Calcification in Aortic Valve Leaflets. Biomechanics, 5(4), 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomechanics5040099