Comparison of Marker-Based and Markerless Motion Capture Systems for Measuring Throwing Kinematics

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Experimental Setup and Procedure

2.3. Motion Capture

2.3.1. Marker-Based System

2.3.2. Markerless System

2.4. Data Processing and Motion Capture Comparison

2.5. Statistical Analysis

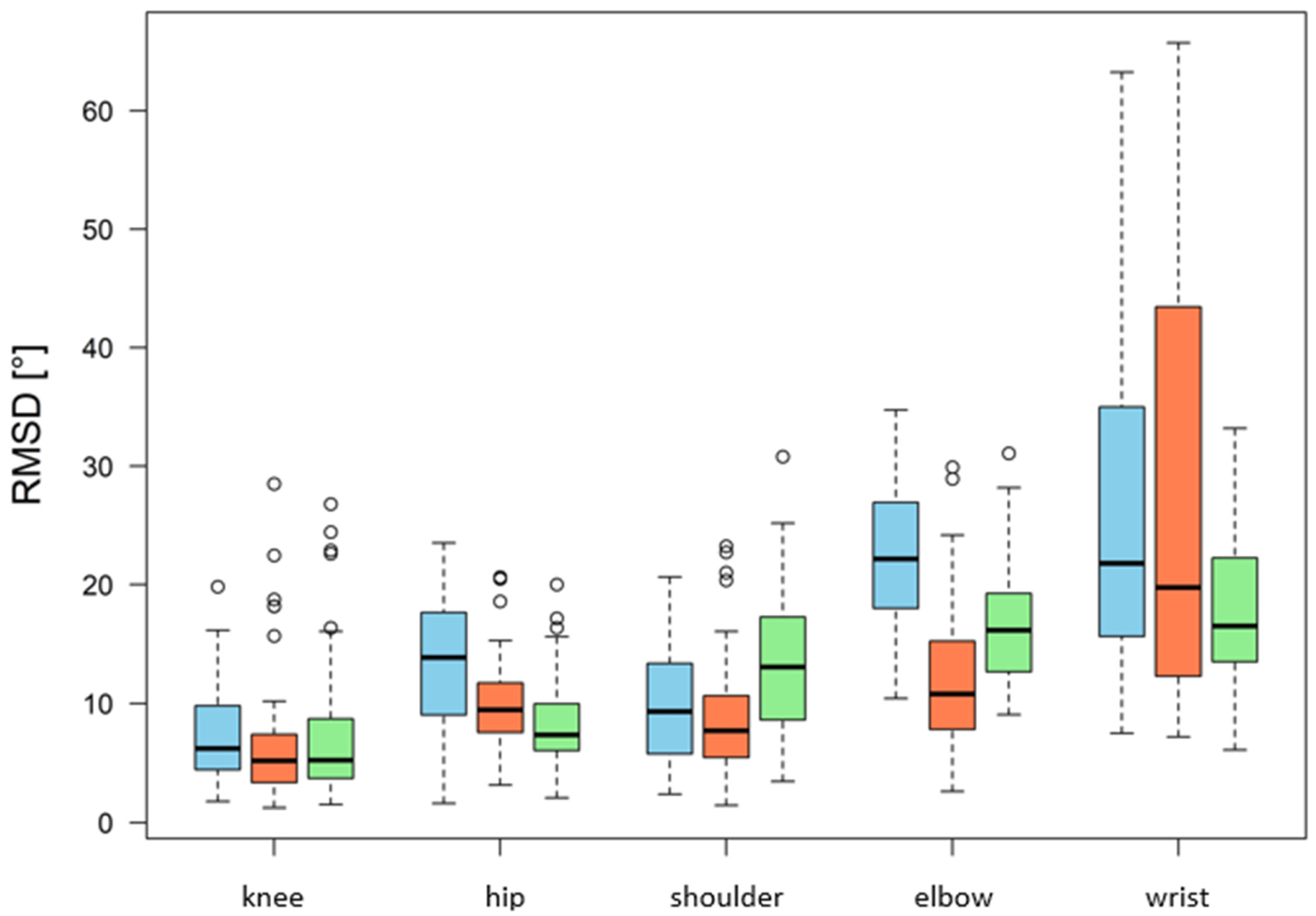

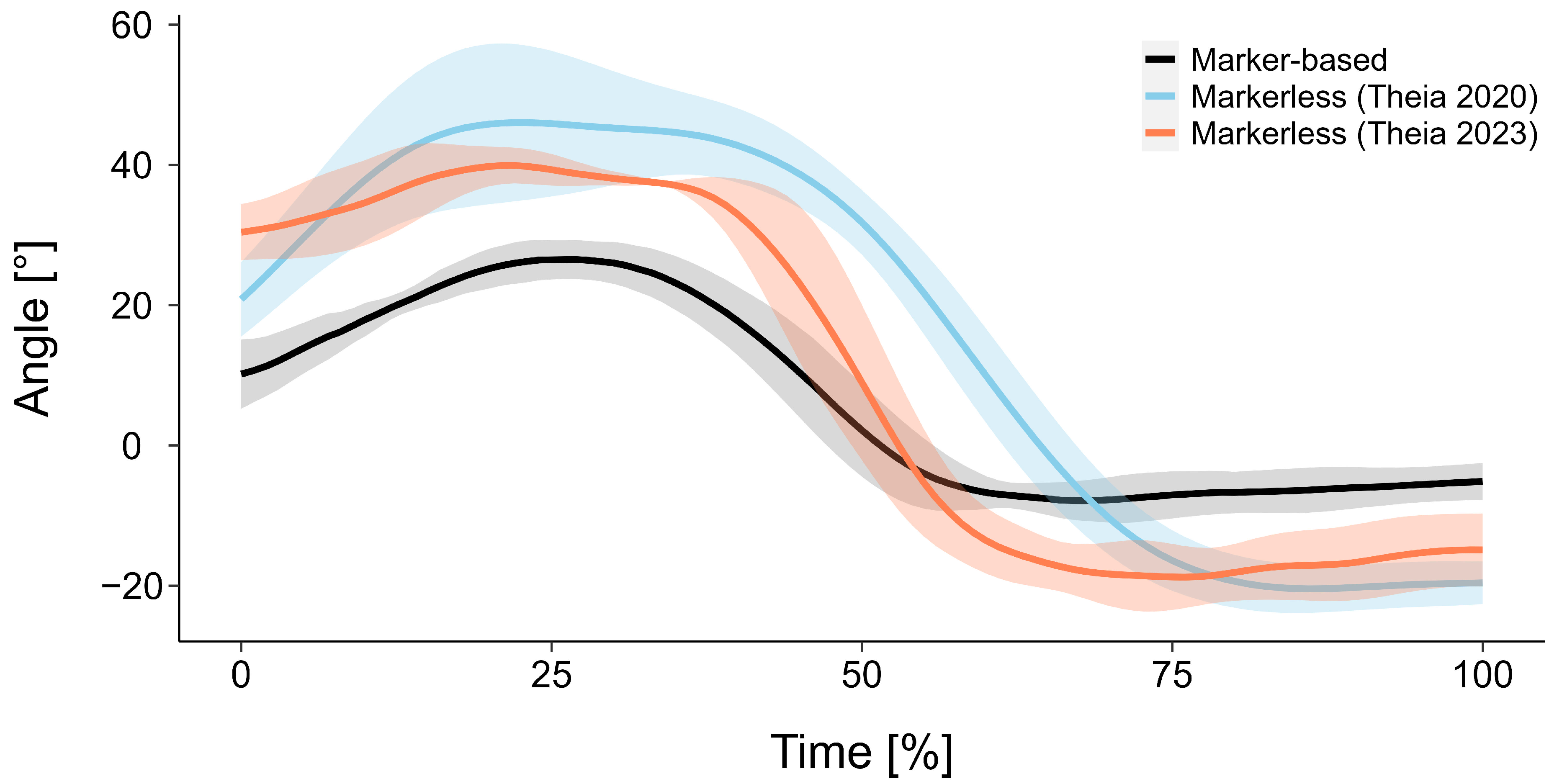

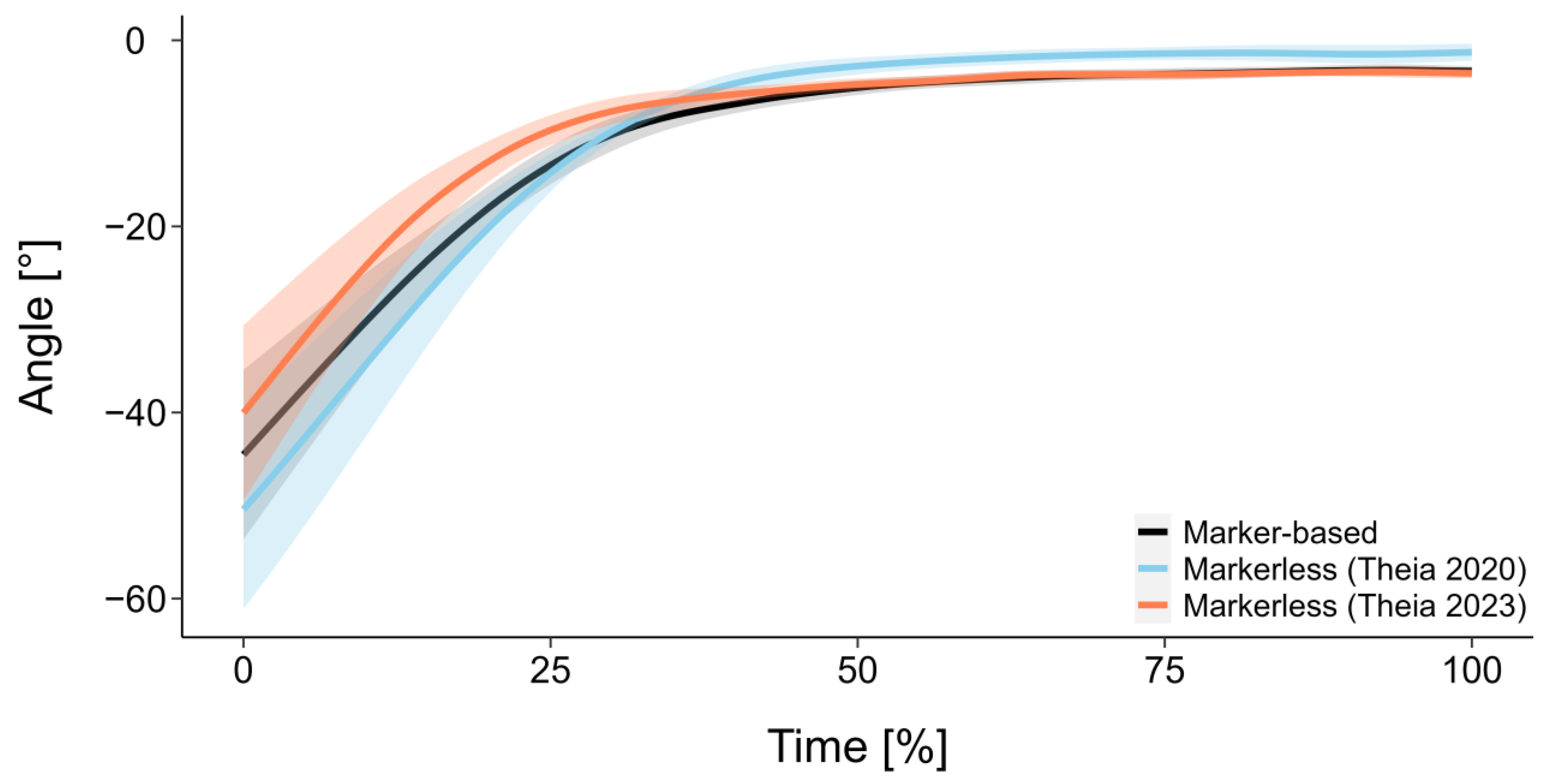

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Meng, Y.; Bíró, I.; Sárosi, J. Markerless measurement techniques for motion analysis in sports science. Analecta Tech. Szeged. 2023, 17, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoma, M.; Llurda-Almuzara, L.; Herrington, L.; Jones, R. Reliability and validity of lower extremity and trunk kinematics measured with markerless motion capture during sports-related and functional tasks: A systematic review. J. Sports Sci. 2025, 43, 1703–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, K.; de Paula Oliveira, T.; Newell, J. Comparison of markerless and marker-based motion capture systems using 95% functional limits of agreement in a linear mixed-effects modelling framework. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 22880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitano-Lago, C.; Willoughby, D.; Kiefer, A.W. A SWOT Analysis of Portable and Low-Cost Markerless Motion Capture Systems to Assess Lower-Limb Musculoskeletal Kinematics in Sport. Front. Sports Act. Living 2022, 3, 809898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guseinov, D.I. Comparative Analysis of Biomechanical Variables in Marker-based and Markerless Motion Capture Systems. Doklady BGUIR 2023, 21, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, V. Accuracy and Precision in Marker-Based Motion Capture. Ph.D. Thesis, Baylor University, Waco, TX, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Burger, B.; Toiviainen, P. MoCap Toolbox—A Matlab Toolbox for Computational Analysis of Movement Data; Logos Verlag Berlin: Stockholm, Sweden, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Nakano, N.; Sakura, T.; Ueda, K.; Omura, L.; Kimura, A.; Iino, Y.; Fukashiro, S.; Yoshioka, S. Evaluation of 3D Markerless Motion Capture Accuracy Using OpenPose With Multiple Video Cameras. Front. Sports Act. Living 2020, 2, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespeau, S.; da Silva, E.S.; Ravel, A.; Rossi, J.; Morin, J.B. Concurrent assessment of sprint running lower-limb and trunk kinematics using marker-based and markerless motion capture. J. Sports Sci. 2025; 1–14, Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, J.; Gattringer, H.; Mueller, A. Optimal Camera Placement for Maximized Motion Capture Volume and Marker Visibility; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, U.; Lee, S.; Kim, S.-A.; Lee, J.-D.; Lee, S. Validity and reliability of the single camera marker less motion capture system using RGB-D sensor to measure shoulder range-of-motion: A protocol for systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine 2023, 102, e33893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wade, L.; Needham, L.; McGuigan, P.; Bilzon, J. Applications and limitations of current markerless motion capture methods for clinical gait biomechanics. PeerJ 2022, 10, e12995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tien, R.; Tekriwal, A.; Calame, D.; Platt, J.; Baker, S.; Seeberger, L.; Kern, D.; Person, A.; Ojemann, S.; Thompson, J.; et al. Deep learning based markerless motion tracking as a clinical tool for movement disorders: Utility, feasibility and early experience. Front. Signal Process. 2022, 2, 884384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanko, R.M.; Laende, E.K.; Davis, E.M.; Selbie, W.S.; Deluzio, K.J. Concurrent assessment of gait kinematics using marker-based and markerless motion capture. J. Biomech. 2021, 127, 110665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Miyakoshi, M.; Iversen, J.R. Approaches for Hybrid Coregistration of Marker-Based and Markerless Coordinates Describing Complex Body/Object Interactions. Sensors 2023, 23, 6542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanko, R.M.; Laende, E.K.; Strutzenberger, G.; Brown, M.; Selbie, W.S.; DePaul, V.; Scott, S.H.; Deluzio, K.J. Assessment of spatiotemporal gait parameters using a deep learning algorithm-based markerless motion capture system. J. Biomech. 2021, 122, 110414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, K.; Hullfish, T.J.; Silva, R.S.; Silbernagel, K.G.; Baxter, J.R. Markerless motion capture estimates of lower extremity kinematics and kinetics are comparable to marker-based across 8 movements. bioRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbarshahi, M.; Schache, A.; Fernandez, J.; Baker, R.; Banks, S.; Pandy, M. Non-invasive assessment of soft-tissue artifact and its effect on knee joint kinematics during functional activity. J. Biomech. 2010, 43, 1292–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Pan, J.; Munkasy, B.; Duffy, K.; Li, L. Comparison of Lower Extremity Joint Moment and Power Estimated by Markerless and Marker-Based Systems during Treadmill Running. Bioengineering 2022, 9, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moro, M.; Marchesi, G.; Hesse, F.; Odone, F.; Casadio, M. Markerless vs. Marker-Based Gait Analysis: A Proof of Concept Study. Sensors 2022, 22, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibler, W.; Sciascia, A.; Grantham, W. The shoulder joint complex in the throwing motion. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2023, 33, 443–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okazaki, V.H.A.; Rodacki, A.L.F. Basketball jump shot performed by adults and children. Hum. Mov. 2018, 2018, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okubo, H.; Hubbard, M. Kinematics of Arm Joint Motions in Basketball Shooting. Procedia Eng. 2015, 112, 443–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahkar, B.K.; Muller, A.; Dumas, R.; Reveret, L.; Robert, T. Accuracy of a markerless motion capture system in estimating upper extremity kinematics during boxing. Front. Sports Act. Living 2022, 4, 939980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camargo, J.; Ramanathan, A.; Csomay-Shanklin, N.; Young, A. Automated gap-filling for marker-based biomechanical motion capture data. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Eng. 2020, 23, 1180–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathis, A.; Schneider, S.; Lauer, J.; Mathis, M.W. A Primer on Motion Capture with Deep Learning: Principles, Pitfalls, and Perspectives. Neuron 2020, 108, 44–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.A.; Kiefer, A.W.; Bullock, G.S.; Kucera, K.L.; Cameron, K.L.; Boling, M.C.; Marshall, S.W.; Padua, D.A. Reliability and predictive validity of trunk and lower extremity kinematics during a jump-landing task using OpenCap markerless motion capture system. J. Biomech. 2026, 194, 113026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokkink, L.B.; Prinsen, C.A.; Bouter, L.M.; Vet, H.C.; Terwee, C.B. The COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments (COSMIN) and how to select an outcome measurement instrument. Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 2016, 20, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, C.; Nolte, K.; Schmidt, M.; Jaitner, T. Lower Baskets and Smaller Balls Influence Mini-Basketball Players’ Throwing Motions. Biomechanics 2023, 3, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antognini, C.; Ortigas-Vásquez, A.; Knowlton, C.; Utz, M.; Sauer, A.; Wimmer, M.A. Comparison of markerless and marker-based motion analysis accounting for differences in local reference frame orientation. J. Biomech. 2025, 185, 112683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, M.; Alt, T.; Nolte, K.; Jaitner, T. Comment on “Hurdle Clearance Detection and Spatiotemporal Analysis in 400 Meters Hurdles Races Using Shoe-Mounted Magnetic and Inertial Sensor”. Sensors 2020, 20, 2995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, M.; Rheinländer, C.; Nolte, K.; Wille, S.; Wehn, N.; Jaitner, T. IMU- based Determination of Stance Duration During Sprinting. Procedia Eng. 2016, 147, 747–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helwig, J.; Vanrenterghem, J.; Anedda, B.; Koska, D.; Hipper, M.; Denis, Y.; Braun, L.; Segers, V.; Gollhofer, A.; Willwacher, S. Comparison of lower body joint kinematics during change of direction tasks estimated using a markerless and a markerbased method. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 34119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanko, R.; Outerleys, J.; Laende, E.; Selbie, W.; Deluzio, K. Comparison of concurrent and asynchronous running kinematics and kinetics from marker-based motion capture and markerless motion capture under two clothing conditions. J. Appl. Biomech. 2024, 40, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Joint | Comparison 1 | Comparison 2 | Comparison 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knee | 5 | 5 | 6 |

| Hip | 3 | 2 | 4 |

| Shoulder | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| Elbow | 8 | 4 | 10 |

| Wrist | 3 | 5 | 2 |

| Joint | Comparison 1 | Comparison 2 | Comparison 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knee | 0.914 | 0.920 | 0.925 |

| Hip | 0.514 | 0.845 | 0.654 |

| Shoulder | 0.693 | 0.714 | 0.888 |

| Elbow | 0.593 | 0.802 | 0.932 |

| Wrist | 0.033 | −0.001 | 0.273 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Thomas, C.; Nolte, K.; Schmidt, M.; Jaitner, T. Comparison of Marker-Based and Markerless Motion Capture Systems for Measuring Throwing Kinematics. Biomechanics 2025, 5, 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomechanics5040100

Thomas C, Nolte K, Schmidt M, Jaitner T. Comparison of Marker-Based and Markerless Motion Capture Systems for Measuring Throwing Kinematics. Biomechanics. 2025; 5(4):100. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomechanics5040100

Chicago/Turabian StyleThomas, Carina, Kevin Nolte, Marcus Schmidt, and Thomas Jaitner. 2025. "Comparison of Marker-Based and Markerless Motion Capture Systems for Measuring Throwing Kinematics" Biomechanics 5, no. 4: 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomechanics5040100

APA StyleThomas, C., Nolte, K., Schmidt, M., & Jaitner, T. (2025). Comparison of Marker-Based and Markerless Motion Capture Systems for Measuring Throwing Kinematics. Biomechanics, 5(4), 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomechanics5040100