Presentation and Initial Validation of a New Observational Situation and Coding System for Assessing Triadic Family Interactions with Adolescents

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Characteristics

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Family Conflict and Alliance Assessment Scales—With Adolescents (FCAAS)

2.3.2. Relationship Assessment Scale

2.3.3. Coparenting Inventory for Parents and Adolescents

2.3.4. Typicality Questionnaire

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Correlations

3.2. Inter-Rater Reliability

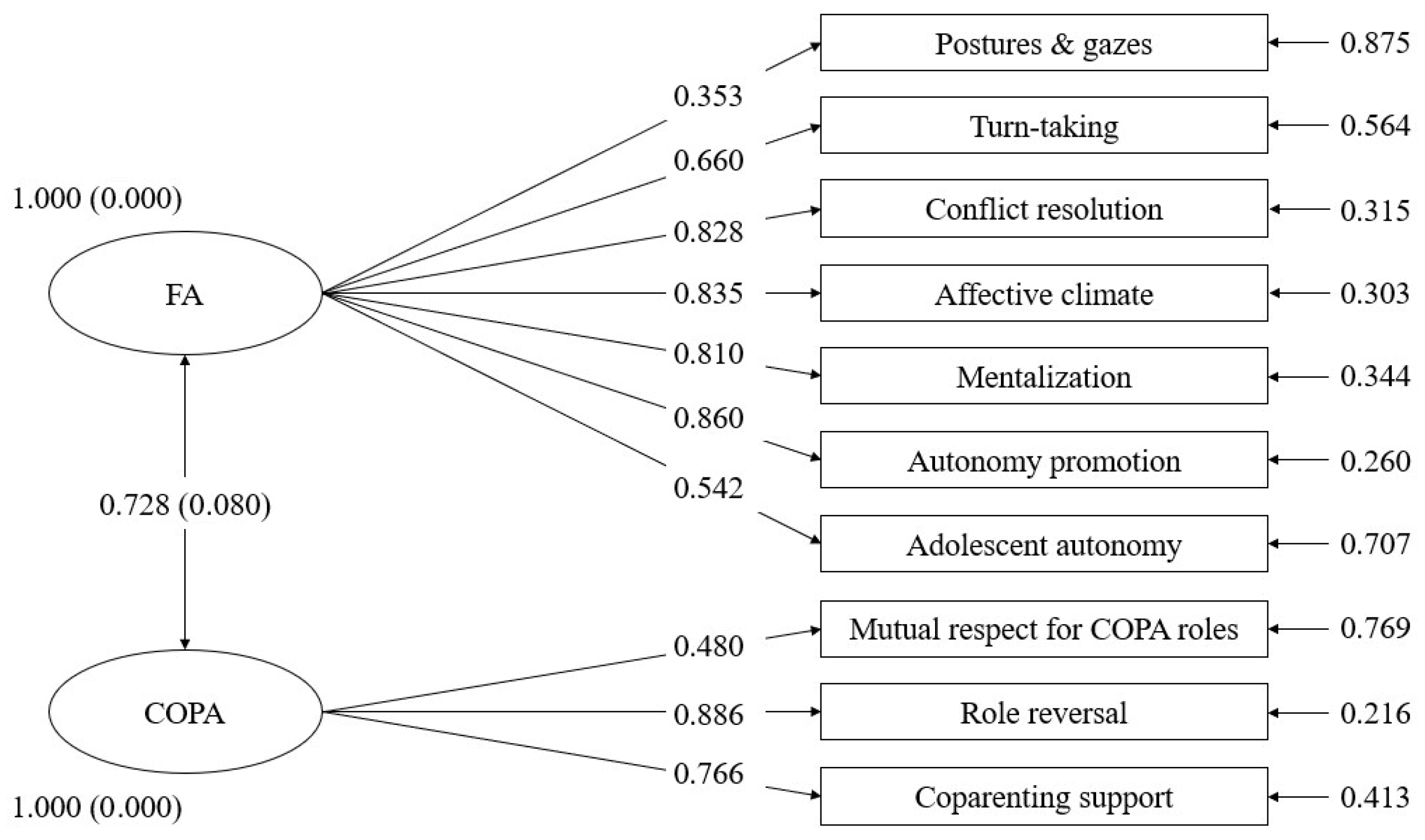

3.3. Factor Structure Validity

3.4. Control Variables

3.5. Criterion Validity: Links Marital Satisfaction

3.6. Construct Validity: Links Coparenting Perceived by the Parents

3.7. Ecological Validity

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CER-VD | Commission cantonale d’éthique du canton de Vaud [Cantonal Commission on Ethics in Human Research of the State of Vaud] |

| CFA | Confirmatory factor analysis |

| CFI | Comparative fit index |

| CIPA | Coparenting inventory for parents and adolescents |

| FA | Family alliance |

| FAAS | Family alliance assessment scales |

| FCAAS | Family conflict and alliance assessment scales |

| HRO | Human research ordinance |

| ICC | Intraclass correlation coefficient |

| LTP | Lausanne trilogue play |

| LTP-CDT | Lausanne trilogue play—conflict discussion task |

| RAS | Relationship assessment scale |

| RMSEA | Root mean square error of approximation |

| SEM | Structural equation modeling |

| SRMR | Standardized root mean square residual |

| TLI | Tucker–Lewis Index |

References

- Van Egeren, L.A.; Hawkins, D.P. Coming to terms with coparenting: Implications of definition and measurement. J. Adult Dev. 2004, 11, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paley, B.; Hajal, N.J. Conceptualizing emotion regulation and coregulation as family-level phenomena. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2022, 25, 19–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tissot, H.; Lapalus, N.; Frascarolo, F.; Despland, J.-N.; Favez, N. Family alliance in infancy and toddlerhood predicts social cognition in adolescence. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2022, 31, 1338–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teubert, D.; Pinquart, M. The association between coparenting and child adjustment: A meta-analysis. Parenting 2010, 10, 286–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Wu, H.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Hou, J. The association between coparenting behavior and internalizing/externalizing problems of children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronaghan, D.; Gaulke, T.; Theule, J. The association between marital satisfaction and coparenting quality: A meta-analysis. J. Fam. Psychol. 2024, 38, 236–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerig, P.K.; Lindahl, K.M. Family Observational Coding Systems: Resources for Systemic Research; Psychology Press: Hove, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Grotevant, H.D.; Carlson, C.I. Family interaction coding systems: A descriptive review. Fam. Process 1987, 26, 49–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampson, R.B.; Beavers, W.R.; Hulgus, Y.F. Insiders’ and outsiders’ views of family: The assessment of family competence and style. J. Fam. Psychol. 1989, 3, 118–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollà Cusí, L.; Günther-Bel, C.; Vilaregut Puigdesens, A.; Campreciós Orriols, M.; Matalí Costa, J.L. Instruments for the assessment of coparenting: A systematic review. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2020, 29, 2487–2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baril, M.E.; Crouter, A.C.; McHale, S.M. Processes linking adolescent well-being, marital love, and coparenting. J. Fam. Psychol. 2007, 21, 645–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fivaz-Depeursinge, E.; Corboz-Warnery, A. The Primary Triangle: A Developmental Systems View of Mothers, Fathers, and Infants; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Tissot, H.; Favez, N. The Lausanne Trilogue Play: Bringing together developmental and systemic perspectives in clinical settings. Aust. N. Z. J. Fam. Ther. 2023, 44, 511–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favez, N.; Lavanchy Scaiola, C.; Tissot, H.; Darwiche, J.; Frascarolo, F. The family alliance assessment scales: Steps toward validity and reliability of an observational assessment tool for early family interactions. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2011, 20, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favez, N.; Lopes, F.; Bernard, M.; Frascarolo, F.; Lavanchy Scaiola, C.; Corboz-Warnery, A.; Fivaz-Depeursinge, E. The development of family alliance from pregnancy to toddlerhood and child outcomes at 5 years. Fam. Process 2012, 51, 542–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favez, N.; Frascarolo, F.; Carneiro, C.; Montfort, V.; Corboz-Warnery, A.; Fivaz-Depeursinge, E. The development of the family alliance from pregnancy to toddlerhood and children outcomes at 18 months. Infant Child Dev. 2006, 15, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensi, M.M.; Orlandi, M.; Rogantini, C.; Provenzi, L.; Chiappedi, M.; Criscuolo, M.; Castiglioni, M.C.; Zanna, V.; Borgatti, R. Assessing family functioning before and after an integrated multidisciplinary family treatment for adolescents with restrictive eating disorders. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gottman, J.M.; Notarius, C.I. Decade review: Observing marital interaction. J. Marriage Fam. 2000, 62, 927–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persram, R.J.; Scirocco, A.; Della Porta, S.; Howe, N. Moving beyond the dyad: Broadening our understanding of family conflict. Hum. Dev. 2019, 63, 38–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branje, S. Development of parent–adolescent relationships: Conflict interactions as a mechanism of change. Child Dev. Perspect. 2018, 12, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warmuth, K.A.; Cummings, E.M.; Davies, P.T. Constructive and destructive interparental conflict, problematic parenting practices, and children’s symptoms of psychopathology. J. Fam. Psychol. 2020, 34, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weymouth, B.B.; Buehler, C.; Zhou, N.; Henson, R.A. A meta-analysis of parent–adolescent conflict: Disagreement, hostility, and youth maladjustment. J. Fam. Theory Rev. 2016, 8, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romet, M.; Favez, N.; Tissot, H. Family Conflict and Alliance Assessment Scales—With Adolescents (FCAAS); FCAAS: Foxborough, MA, USA; Lausanne, Switzerland, 2023; unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Thielke, R.; Payne, J.; Gonzalez, N.; Conde, J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inform. 2009, 42, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrick, S.S. A generic measure of relationship satisfaction. J. Marriage Fam. 1988, 50, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saramago, M.; Lemétayer, F.; Gana, K. Adaptation et validation de la version française de l’échelle d’évaluation de la relation. Psychol. Française 2021, 66, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teubert, D.; Pinquart, M. The Coparenting Inventory for Parents and Adolescents (CI-PA): Reliability and validity. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2011, 27, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, G.; Antonietti, J.-P.; Sznitman, G.A.; Petegem, S.V.; Darwiche, J. The French version of the coparenting inventory for parents and adolescents (CI-PA): Psychometric properties and a cluster analytic approach. J. Fam. Stud. 2020, 28, 652–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favez, N.; Tissot, H.; Frascarolo, F. Is it typical? The ecological validity of the observation of mother-father-infant interactions in the Lausanne Trilogue Play. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 2019, 16, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ten Hove, D.; Jorgensen, T.D.; van der Ark, L.A. Updated guidelines on selecting an intraclass correlation coefficient for interrater reliability, with applications to incomplete observational designs. Psychol. Methods 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B.O. Mplus User’s Guide, 8th ed.; Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1998–2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.-t.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittaker, T.A. Using the modification index and standardized expected parameter change for model modification. J. Exp. Educ. 2012, 80, 26–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.F. Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 2007, 14, 464–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, G.W.; Rensvold, R.B. Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 2002, 9, 233–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minuchin, S. Families & Family Therapy; Harvard University Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Ece, C.; Gürmen, M.S.; Acar, İ.H.; Buyukcan-Tetik, A. Examining the dyadic association between marital satisfaction and coparenting of parents with young children. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 43, 1473–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beam, C.R.; Marcus, K.; Turkheimer, E.; Emery, R.E. Gender differences in the structure of marital quality. Behav. Genet. 2018, 48, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetherington, E.M. Family functioning and the adjustment of adolescent siblings in diverse types of families. Monogr. Soc. Res. Child Dev. 1999, 64, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McHale, J.; Tissot, H.; Mazzoni, S.; Hedenbro, M.; Salman-Engin, S.; Philipp, D.A.; Darwiche, J.; Keren, M.; Collins, R.; Coates, E.; et al. Framing the work: A coparenting model for guiding infant mental health engagement with families. Infant Ment. Health J. 2023, 44, 638–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodwin, C. Restarts, pauses, and the achievement of a state of mutual gaze at turn-beginning. Sociol. Inq. 1980, 50, 272–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, C. Conversational Organization: Interaction Between Speakers and Hearers; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, J.D. Getting down to business: Talk, gaze, and body orientation during openings of doctor-patient consultations. Hum. Commun. Res. 1998, 25, 97–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beveridge, R.M.; Berg, C.A. Parent–adolescent collaboration: An interpersonal model for understanding optimal interactions. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2007, 10, 25–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favez, N.; Frascarolo, F.; Tissot, H. The family alliance model: A way to study and characterize early family interactions. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coan, J.A.; Gottman, J.M. The specific affect coding system (SPAFF). In Handbook of Emotion Elicitation and Assessment; Coan, J.A., Allen, J.J.B., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2007; pp. 267–285. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, D.C.; Bell, L.G. Micro and macro measurement of family systems concepts. J. Fam. Psychol. 1989, 3, 137–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K. Why Do We Overlap Each Other?: Collaborative Overlapping Talk in English as a Lingua Franca (ELF) Communication. Korean J. Engl. Lang. Linguist. 2020, 20, 613–641. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://enfance-et-partage.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/guide-parentalite-version-def.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Forbes, C.; Vuchinich, S.; Kneedler, B. Assessing families with the family problem solving code. In Family Observational Coding Systems: Resources for Systemic Research; Kerig, P., Lindahl, K., Eds.; Psychology Press: Hove, UK, 2000; pp. 59–75. [Google Scholar]

- Marceau, K.; Zahn-Waxler, C.; Shirtcliff, E.A.; Schreiber, J.E.; Hastings, P.; Klimes-Dougan, B. Adolescents’, mothers’, and fathers’ gendered coping strategies during conflict: Youth and parent influences on conflict resolution and psychopathology. Dev. Psychopathol. 2015, 27, 1025–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.A. Negative effects of destructive criticism: Impact on conflict, self-efficacy, and task performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 1988, 73, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonagy, P.; Steele, M.; Steele, H.; Moran, G.S.; Higgitt, A.C. The capacity for understanding mental states: The reflective self in parent and child and its significance for security of attachment. Infant Ment. Health J. 1991, 12, 201–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanwoerden, S. The Development and Validation of an Observational Coding System for Real-Time Parent-Adolescent Mentalizing. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Houston, Houston, TX, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ballespí, S.; Vives, J.; Debbané, M.; Sharp, C.; Barrantes-Vidal, N. Beyond diagnosis: Mentalization and mental health from a transdiagnostic point of view in adolescents from non-clinical population. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 270, 755–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuchinich, S.; Vuchinich, R.; Wood, B. The Interparental Relationship and Family Problem Solving with Preadolescent Males. Child Dev. 1993, 64, 1389–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doane, J.A. Family Interaction and Communication Deviance in Disturbed and Normal Families: A Review of Research. Fam. Process. 1978, 17, 357–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brotherton, W.D. The Assessment of Parental Triangulation of Children; The Florida State University: Tallahassee, FL, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Kerr, M.E.; Bowen, M. Family Evaluation; WW Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Minuchin, S.; Baker, L.; Rosman, B.L.; Liebman, R.; Milman, L.; Todd, T.C. A conceptual model of psychosomatic illness in children: Family organization and family therapy. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1975, 32, 1031–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.P.; Hauser, S.T.; Bell, K.L.; O’Connor, T.G. Longitudinal assessment of autonomy and relatedness in adolescent-family interactions as predictors of adolescent ego development and self-esteem. Child Dev. 1994, 65, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, J.P.; Hauser, S.T. Autonomy and relatedness in adolescent-family interactions as predictors of young adults’ states of mind regarding attachment. Dev. Psychopathol. 1996, 8, 793–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengtson, P.L.; Grotevant, H.D. The individuality and connectedness Q-sort: A measure for assessing individuality and con-nectedness in dyadic relationships. Pers. Relatsh. 1999, 6, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaplin, T.M.; Sinha, R.; Simmons, J.A.; Healy, S.M.; Mayes, L.C.; Hommer, R.E.; Crowley, M.J. Parent–adolescent conflict interactions and adolescent alcohol use. Addict. Behav. 2012, 37, 605–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maharaj, S.; Rodin, G.; Connolly, J.; Olmsted, M.; Daneman, D. Eating problems and the observed quality of mother–daughter interactions among girls with type 1 diabetes. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2001, 69, 950–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravindran, N.; Hu, Y.; McElwain, N.L.; Telzer, E.H. Dynamics of mother–adolescent and father–adolescent autonomy and control during a conflict discussion task. J. Fam. Psychol. 2020, 34, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Petegem, S.; Baudat, S.; Zimmermann, G. Interdit d’interdire? Vers une meilleure compréhension de l’autonomie et des règles au sein des relations parents-adolescents. Can. Psychol. 2019, 60, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Rating Scales | Brief Description of Appropriate Criteria |

|---|---|

| Postures & gazes | At the non-verbal level, participants signal their availability to interact, and everyone is involved in the interaction |

| Turn-taking | At the verbal level, everyone is engaged, talk time is balanced and there are few interruptions or monologues |

| Mutual respect for coparenting roles | Both parents are compliant with the LTP-CDT instructions regarding the various interactive roles (third-party or active) |

| Conflict resolution | Thanks to cooperation in the family, a negotiation process allows for the problem to be solved through dialogue and co-construction of a viable solution |

| Affective climate | The emotional climate is positive and warm, while affects are authentic; family members seem to enjoy each other’s presence |

| Mentalization | Family members pay attention to their own and others’ mental states; there is a climate of validation and empathy |

| Role reversal | The adolescent is not involved in the parental subsystem |

| Coparenting support | Parents agree about education or at least they coordinate and support each other |

| Autonomy promotion | Parents show respect for the adolescent’s individuality, and help them identify and express their needs and preferences; limit management is clear and flexible |

| Adolescent autonomy | The adolescent demonstrates autonomy, independence, and self-approval |

| FCAAS Scales | ICC | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | SE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Postures & Gazes | 0.64 | 0.33 | 0.90 | 0.13 |

| Turn-taking | 0.83 | 0.68 | 0.92 | 0.05 |

| Mutual respect for coparenting roles | 0.82 | 0.66 | 0.97 | 0.08 |

| Conflict resolution | 0.90 | 0.81 | 0.96 | 0.03 |

| Affective climate | 0.86 | 0.75 | 0.94 | 0.05 |

| Mentalization | 0.88 | 0.78 | 0.95 | 0.04 |

| Role reversal | 0.90 | 0.82 | 0.96 | 0.03 |

| Coparenting support | 0.85 | 0.73 | 0.94 | 0.05 |

| Autonomy promotion | 0.86 | 0.73 | 0.94 | 0.05 |

| Adolescent autonomy | 0.81 | 0.64 | 0.92 | 0.06 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Romet, M.; Favez, N.; Foletta, A.; Burnier, A.; Mrozek, A.; Schumacher, M.; Tissot, H. Presentation and Initial Validation of a New Observational Situation and Coding System for Assessing Triadic Family Interactions with Adolescents. Adolescents 2025, 5, 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents5040052

Romet M, Favez N, Foletta A, Burnier A, Mrozek A, Schumacher M, Tissot H. Presentation and Initial Validation of a New Observational Situation and Coding System for Assessing Triadic Family Interactions with Adolescents. Adolescents. 2025; 5(4):52. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents5040052

Chicago/Turabian StyleRomet, Michaël, Nicolas Favez, Amalia Foletta, Annie Burnier, Aleksandra Mrozek, Marie Schumacher, and Hervé Tissot. 2025. "Presentation and Initial Validation of a New Observational Situation and Coding System for Assessing Triadic Family Interactions with Adolescents" Adolescents 5, no. 4: 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents5040052

APA StyleRomet, M., Favez, N., Foletta, A., Burnier, A., Mrozek, A., Schumacher, M., & Tissot, H. (2025). Presentation and Initial Validation of a New Observational Situation and Coding System for Assessing Triadic Family Interactions with Adolescents. Adolescents, 5(4), 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents5040052