Abstract

While loneliness is a known correlate of social withdrawal, the underlying mechanisms, particularly within college student populations, remain inadequately understood. This study addresses this gap by investigating the mediating role of internet addiction and the moderating role of sex in the relationship between loneliness and social withdrawal. A cross-sectional survey was conducted with 1978 Chinese college students. Analyses were performed using SEM (AMOS) and the PROCESS for SPSS to test a moderated mediation model. Results confirmed a significant positive association between loneliness and social withdrawal. Internet addiction was found to significantly mediate this relationship, explaining 50.7% of the total effect. Moreover, sex moderated the indirect pathway, suggesting that the strength of the mediating effect varied by sex. These findings provide empirical support for the Evolutionary Theory of Loneliness by elucidating the psychological processes linking loneliness to social withdrawal within a collectivist cultural context. The study also offers practical implications for developing targeted mental health interventions to reduce social withdrawal and promote social participation among college students.

1. Introduction

Loneliness is a subjective, negative emotional state arising from perceived dissatisfaction with the quantity or quality of one’s social relationships, and it does not necessarily correspond to the objective number of relationships or their measured quality [1,2]. It has emerged as a global public health concern and is particularly salient among college students, who typically straddle late adolescence (~16–18) and emerging adulthood (~18–25)—a stage marked by identity exploration, peer-network reorganization, and increasing autonomy that can heighten vulnerability to loneliness [3,4,5,6]. Recent epidemiological indicators underscore this burden: in a U.S. national survey, 65% of students reported feeling “very lonely” in the past 12 months [7]; in the U.K., nearly one-quarter of university students reported feeling lonely “always” or “most of the time” [8]; and, in Asia, a large-scale national online survey found that 10.2% of the population reported loneliness [9].

Contemporary reviews suggest that loneliness is consequential in adolescent and emerging adulthood, with consistent links to poorer mental health and functioning, underscoring its significance for students navigating new academic and social environments [10,11]. Loneliness reflects the perception of deficient social relationships, while social withdrawal means the behavior of isolating oneself from a peer group [12]. Some scholars suggest that an indirect pathway leading to adolescent loneliness is social withdrawal in childhood [13]. Rubin et al. [12] (2009) emphasizes that peer relationships during childhood are critical for emotional and social development. Children who exhibit high levels of social withdrawal during this formative period may have limited opportunities for peer interaction, placing them at increased risk for internalizing problems such as loneliness [13].

It has also been proposed that feelings of loneliness might exacerbate social withdrawal in youth [10], suggesting that loneliness might not only result from extreme avoidance of social relationships but could also activate early withdrawal behaviors after the initial perception of social disconnection [14]. According to Cacioppo’s Evolutionary Theory of Loneliness (ETL), compared with non-lonely individuals, lonely individuals perceive the social world as more threatening, imagine more negative social interactions, and remember more negative social information [15]. Experimental research by Arpin and Mohr [16] further supports this view, showing that lonely individuals evaluate social interactions more negatively and exhibit diminished responsiveness to others. ETL further posits that such negative social expectations generated by lonely individuals often influence how those around them behave, confirming the lonely individuals’ anticipated expectations and thus initiating a self-fulfiling prophecy [17]. Lonely individuals actively maintain distance from potential social partners, believing that the social distance is caused by others rather than themselves [18].

Regardless of causal direction, loneliness and social withdrawal are closely associated, yet the mechanisms underlying this link—particularly mediating and moderating processes—remain insufficiently understood, and evidence in college samples is limited. Because college students occupy the developmental window spanning late adolescence to emerging adulthood, this study examines the relations among loneliness, internet addiction, and social withdrawal during a stage when adolescent vulnerabilities remain active as adult roles crystallize, and tests whether sex moderates the association between loneliness and social withdrawal. By doing so, the study aims to identify developmentally informed, technology-aware intervention points to mitigate the impact of loneliness in the digital era.

1.1. The Mediating Role of Internet Addiction

Internet addiction has emerged as a contemporary psychological and behavioral challenge, with college students identified as a particularly high-risk group [19]. It is commonly defined as excessive and problematic Internet use that is characterized by concerns, impulses, or uncontrolled behaviors [20]. Individuals with internet addiction often exhibit weaker interpersonal skills and heightened sensitivity to real-life frustration, both of which contribute to a tendency toward social withdrawal [21]. Previous studies have consistently found a positive association between internet addiction and social withdrawal [22].

Moreover, internet addiction is frequently linked to heightened feelings of loneliness [23]. Empirical research has shown that loneliness is a significant positive predictor of internet addiction, indicating that individuals who feel lonely are more likely to engage in problematic online behaviors [24,25,26]. According to Compensatory Internet Use Theory (CIUT), compulsive internet use may serve to compensate for unmet psychological needs or to regulate negative affect and external stressors [27]. Lonely individuals may turn to the internet as a temporary emotional relief mechanism [28]. While such online engagement may initially offer short-term comfort, it tends to reinforce the behavior, leading to overuse and further deterioration of real-world social functioning [29]. Rather than alleviating loneliness, excessive internet use may deepen the disconnect from meaningful interpersonal relationships in the offline world, thereby intensifying emotional alienation [30]. Guided byETL, CIUT and this body of evidence, we propose the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 1.

Loneliness will be positively related to social withdrawal.

Hypothesis 2.

Loneliness will be positively related to internet addiction.

Hypothesis 3.

Internet addiction will be positively related to social withdrawal.

Hypothesis 4.

The relation between loneliness and social withdrawal will be mediated by internet addiction.

1.2. The Moderating Role of Sex

Sex is defined as male or female based on genetics, anatomy, and physiology, whereas gender is a social construct referring to socially constructed roles, identities, and behaviors [31]. Given growing evidence for the existence of nonbinary gender identities and intersex populations [32], and to avoid ambiguity, the questionnaire item in this study was labeled: “Please select your biological sex.” Prior research has identified notable sex differences in both loneliness and internet use among college students. For instance, a comprehensive survey of first- and second-year Chinese college students indicated significantly lower loneliness scores among male students than female students [33]. This pattern is not unique to China, as an international study also recognizes female sex as a risk factor for elevated loneliness among students [34]. However, it is essential to note that literature on sex differences in loneliness presents mixed results [35,36,37]. While some studies report no significant sex disparities [38], others suggest that males experience greater loneliness [39].

In the context of internet addiction, findings are similarly inconsistent. A 2024 study of Chinese college students reported that female students scored higher on measures of internet addiction compared to males [40]. In contrast, a meta-analysis revealed the opposite trend, suggesting that males were more susceptible to internet addiction in the Chinese context [41]. Despite these discrepancies in prevalence, there is consensus on the sexed patterns of online activity. Male students are more likely to engage in activities such as gaming or information browsing, while female students tend to use the internet for social networking, messaging, and online shopping [19,42,43].

Taken together, these findings suggest that sex plays a non-negligible role in both loneliness and internet addiction. While previous studies have explored sex differences at the level of individual variables, there is a lack of research examining how sex might moderate the relationship between these variables and, by extension, influence social withdrawal. Based on this gap, the present study proposes:

Hypothesis 5.

Sex will moderate the indirect effect of internet addiction in the relationship between loneliness and social withdrawal.

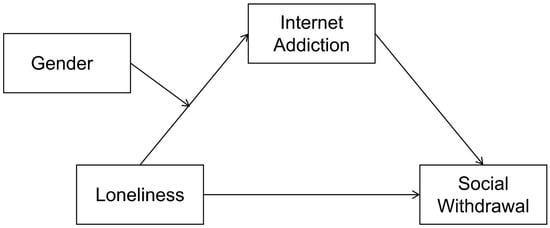

Figure 1 displays the study’s hypothesized model.

Figure 1.

Hypothesized moderated mediation model.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

This study used a cross-sectional survey of undergraduate students enrolled at four colleges in Guangdong Province, China. In the first stage, four colleges were selected from a provincial list using simple random sampling. The participating colleges varied in size and disciplinary profiles and were in both urban and non-urban settings. In the second stage, convenience sampling was employed within each college, with the number of participants proportionally reflecting each college’s enrollment size.

The Mental Health Education course teacher agreed to assist with recruitment and distributed the anonymous online survey link through departmental communication channels (e.g., WeChat groups and learning platforms). Because Mental Health Education is a general-education course required for students across majors in Chinese colleges, this approach enabled the sample to include participants from multiple disciplines. The invitation described the study’s aims, procedures, and confidentiality. Students provided informed consent electronically before accessing the questionnaire, which was completed online and anonymously. No course credit or monetary incentives were offered.

A total of 2116 college students completed the questionnaire. Following a priori quality checks, we removed cases exhibiting identical response patterns across all substantive items (i.e., straight lining with zero within-person variance across multi-item scales), which are widely interpreted as indicators of careless/inattentive responding that can inflate reliability and bias covariance estimates [44]. This yielded 1978 valid questionnaires (93.48% of submissions). Participants (aged 17–26) included 625 males (31.6%) and 1353 females (68.4%). In terms of grade level, 1353 (68.4%) were first-year students, 493 (24.9%) were second-year students, and 132 (6.7%) were third-year students. Additionally, 217 (11%) were only children, while 1761 (89%) were not. Finally, 1419 (71.7%) were from rural areas, and 559 (28.3%) were from urban areas.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Loneliness

This study selected the Chinese 6-item short version of the University of California, Los Angeles Loneliness Scale (ULS-6) [45]. The questions were: (1) Do you often feel that you lack a partner? (2) Do you often feel that no one can be trusted? (3) Do you often feel left out? (4) Do you often feel distant from others? (5) Do you often feel unhappy because of loneliness? and (6) Do you often feel that no one cares about you even though you are surrounded by people? This six-item scale uses a four-point Likert rating (1 = never, 4 = always), with total scores (6–24) reflecting loneliness severity. A higher score indicates higher levels of loneliness. In this study, it exhibited high reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.942).

2.2.2. Internet Addiction

The Chinese Internet Addiction Scale-Revised (CIAS-R) was developed by Shuhui et al. at National Taiwan University, based on the diagnostic criteria of various addictions in the DSM-IV and clinical case observations [46]. In this study, the revised version of the CIAS-R, adapted by mainland scholars Yu Bai and Fumin Fan (2005) [47] for use with mainland Chinese university students, is employed. This version is categorized into two subscales with four dimensions: the “Core Symptoms of Internet Addiction” subscale [48], which includes the factors “Compulsive Internet Use and Withdrawal Symptoms” and “Tolerance of Internet Addiction,” and the “Related Problems of Internet Addiction “ subscale, which includes the factors “Interpersonal and Health Problems” and “Time Management Problems.” In this study, the Cronbach’s α coefficient of the scale was 0.957.

2.2.3. Social Withdrawal

The social withdrawal scale for college students (SWSCS), is an instrument developed by Chinese scholar Tian Yuan through a rigorous process specifically created to measure social withdrawal in college students [49]. The scale includes three constructs: avoidance of unfamiliar environments, being outliers, and avoidance of public speaking. The 16-item scale uses a 5-point Likert rating, ranging from “1” (“completely inconsistent”) to “5” (“completely consistent”). A higher score indicates greater social withdrawal severity. The items on the SWSCS are grouped into three constructs as follows: avoidance of unfamiliar environments, outliers, and avoidance of public speaking. In this study, the Cronbach’s α coefficient of the scale was 0.963.

2.3. Main Statistical Analyses

We assessed potential common-method bias (CMB) using (a) an unrotated Harman’s single-factor test and (b) a single-factor Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) in which all items loaded on one latent factor, and whose fit was compared to the theoretical multi-factor measurement model. A substantially poorer fit of the single-factor model indicated that a single common factor was unlikely to account for the observed covariation. Additionally, the reliability and validity of all variables were examined. Descriptive statistics and Pearson correlation analyses were conducted using SPSS 29.0 to examine the relationships among loneliness, internet addiction, and social withdrawal.

Primary hypothesis tests were conducted in Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) (AMOS 26.0). The measurement model was estimated first, followed by the structural model, testing the indirect effect of loneliness on social withdrawal through internet addiction. To test sex-conditioned indirect effects, we first conducted a multi-group SEM by sex. A critical prerequisite, measurement invariance across sex groups, was rigorously assessed using a stepwise procedure. We sequentially constrained models for configural, metric, and scalar invariance, deeming invariance supported if the change in CFI did not exceed 0.010 and the change in RMSEA did not exceed 0.015. Upon establishing sufficient invariance, we proceeded to test for significant differences in the structural path estimates between the male and female models. To complement this analysis and provide a direct test of the moderated mediation hypothesis, we subsequently utilized the PROCESS macro (Model 7) in SPSS 29.0 with observed composite scores. This procedure yielded an index of moderated mediation, which formally quantifies the difference in the indirect effect by sex. For all inferential tests of indirect effects, we generated 95% percentile bootstrap confidence intervals from 5000 resamples, with significance inferred by confidence intervals that did not straddle zero.

3. Results

3.1. Reliability, Validity, and Common Method Variance Analysis

According to the data results in the measures part, the Cronbach’s α coefficient of the three variable scales is all greater than 0.90. Therefore, the scales used in this study have high reliability, and the measurement data are reliable.

As shown in Table 1, the CFA models for the three scales—loneliness, internet addiction, and social withdrawal—demonstrated an acceptable to good fit. We applied conventional decision rules—RMSEA < 0.08, RMR < 0.08, incremental fit indices ≥ 0.90, and CMIN/DF (χ2/df) < 3.0 for good fit and < 5.0 for acceptable fit [50,51]. Across the three models, χ2/df ranged from 4.19 to 4.95, RMSEA from 0.040 to 0.045, and absolute/incremental indices were high (GFI = 0.970–0.997; NFI = 0.978–0.998), meeting the ≥ 0.90 threshold. Notably, the RMSEA values also satisfy the more conservative ≤ 0.06 guideline often cited for good fit. Taken together, these statistics support an adequate-to-good representation of the data for each construct.

Table 1.

Measurement Model Evaluation by CFA.

In addition, the average variance extracted (AVE), and composite reliability (CR) of loneliness, internet addiction, and social withdrawal scales are all greater than 0.50 and 0.90, indicating that the scale has ideal convergence validity. At the same time, the correlation coefficient of loneliness, internet addiction, and social withdrawal are less than the square root of AVE corresponding to each variable, which indicates that the scales of each variable have ideal discriminant validity [52]. Collectively, these results confirm satisfactory measurement quality for the latent constructs.

Before hypothesis testing, we conducted CFA in AMOS 26.0 to evaluate the fit of the measurement model to the observed data. As shown in Table 2, the three-factor model demonstrated superior fit relative to all two-factor and single-factor alternatives (χ2/df = 4.858, RMSEA = 0.044, CFI = 0.960, TLI = 0.954, IFI = 0.960, NFI = 0.950), indicating a more adequate representation of the data and satisfactory discriminant validity among the three constructs.

Table 2.

Discriminant Validity and Common Method Bias Tested via CFA.

As some measurement items in the questionnaire used in this study have similar contexts, and the questionnaire data were collected in the same period of time, which were affected by the subjective factors of the subjects, the data may have common methodological biases. To assess CMB, we first applied Harman’s single-factor test. An unrotated exploratory factor analysis extracted 11 factors, with the first factor accounting for 26.359% of the variance—well below the 50% benchmark—suggesting that a single factor does not dominate the covariance among measures. We then fit a single-factor CFA in AMOS by loading all items onto one latent factor; its fit indices were the worst among all competing models, further arguing against substantial CMB. Finally, we compared the baseline three-factor model with a common-method factor model (i.e., adding an orthogonal method factor loading on all indicators). Model fit showed no meaningful improvement, indicating that any method variance is minimal. Results of these latter two steps are summarized in Table 2.

3.2. Preliminary Analyses

Table 3 presents descriptive statistics and correlations, showing loneliness was positively correlated with both internet addiction (r = 0.466, p < 0.001) and social withdrawal (r = 0.468, p < 0.001). Internet addiction was positively correlated with social withdrawal (r = 0.576, p < 0.001). Thus, Hypothesis 1, 2 and 3 were supported.

Table 3.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis Results for Each Variable.

3.3. Analysis of the Effect of Mediation

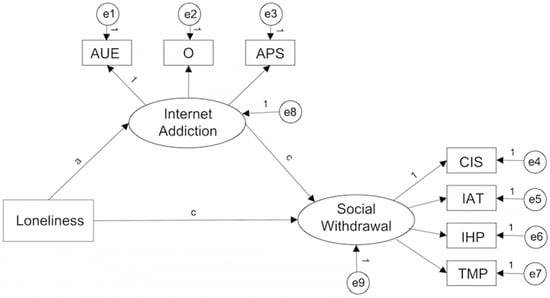

To investigate the mediating effect of internet addiction on the relationship between loneliness and social withdrawal, we conducted a structural equation modeling (SEM) analysis (see Figure 2). The results revealed a mixed model fit; while incremental fit indices were acceptable (GFI = 0.968, CFI = 0.980, TLI = 0.969), absolute fit indices suggested a need for model improvement (χ2/df = 15.159; RMSEA = 0.085, 90% CI [0.076, 0.094]). Despite the modest overall fit, the path analysis confirmed a significant total effect of loneliness on social withdrawal (Estimate = 0.353, p < 0.001). Crucially, the indirect effect of loneliness on social withdrawal via internet addiction was also significant (Estimate = 0.179, p < 0.001), representing 50.7% of the total effect. This indicates that internet addiction serves as a significant partial mediator in the pathway from loneliness to social withdrawal, lending support to Hypothesis 4.

Figure 2.

Path Road for mediation model. Abbreviations: AUE = Avoidance of Unfamiliar Environments, O = Outliers, APS = Avoidance of Public Speaking, CIS = Compulsive Internet surfing and Internet addiction withdrawal response, IAT = Internet addiction tolerance, IHP = Interpersonal and Health Problems, TMP = Time Management Problems, e1–e9 = error terms for the observed variables and latent constructs.

3.4. Analysis of the Effect of Moderated Mediation

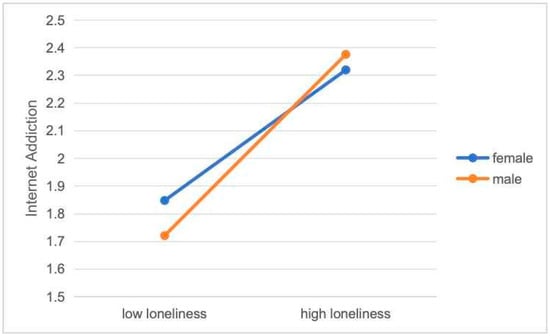

To examine the moderating role of sex, we first conducted a multi-group SEM analysis to test for overall model invariance across sexes. A significant chi-square difference test (Δχ2 (3) = 22.654, p < 0.001) provided initial evidence that the structural pathways were not equivalent across groups. To pinpoint the specific moderated pathway, we subsequently employed Hayes’s PROCESS macro (Model 7) for a moderated mediation analysis. The index of moderated mediation was −0.088, with 95% CI (−0.142, −0.035), indicating a statistically significant moderating effect. As illustrated in Figure 2, with increasing levels of loneliness, male students exhibited a significantly greater increase in internet addiction compared to female students. Therefore, Hypothesis 5 was supported, providing empirical evidence for the moderated mediation model (see Table 4 and Table 5 and Figure 3).

Table 4.

The moderation effect of Sex.

Table 5.

The conditional indirect effects.

Figure 3.

Sex’s moderation in loneliness and internet addiction.

4. Discussion

Previous studies have consistently demonstrated a strong association between loneliness and social withdrawal [53,54]. Some researchers have shown that loneliness may lead to increased social withdrawal [16,55]. However, the underlying mechanisms, particularly the mediating and moderating processes involved in the relationship between loneliness and social withdrawal, remain underexplored, especially within the context of college students. To address this gap, the present study, within a correlational framework, estimated a moderated-mediation model to examine how loneliness, internet addiction, and social withdrawal correlate and whether these links differ by sex.

4.1. Relationship Between Loneliness and Social Withdrawal

Results revealed a significant positive association between loneliness and social withdrawal, indicating that higher levels of loneliness are associated with greater social withdrawal. This finding is consistent with ETL and previous studies [10,16,55] and extends their conclusions to the college student population. Loneliness arises when individuals perceive a gap between their desired social connections and their actual relational experiences [56]. When a student perceives that their real-life relationships fail to meet their need for intimacy and belonging, a profound sense of loneliness and dissatisfaction emerges. This sense of loneliness increases both physiological and psychological sensitivity to perceived social threats [57]. Research has shown that perceiving oneself as socially isolated can increase vigilance for potential threats and feelings of insecurity, and one often chooses to withdraw from social situations as a form of self-protection [58]. Such interpretive biases coincide with avoidance tendencies and are found alongside higher withdrawal.

In more collectivist contexts such as China, relational obligations, group belonging, and “face” (mianzi) carry substantial value and structure everyday interaction norms. Foundational work characterizes Chinese collectivism as emphasizing interdependence and ingroup harmony, with self-regulation tuned to relational consequences and reputation management [59]. Within this cultural script, concerns about losing face and reluctance to burden others can align closely with avoidance-oriented tendencies in social situations, helping to explain why loneliness and withdrawal may covary in college settings. Qualitative and mixed-methods work with Chinese college students similarly documents how face concerns, stigma, and anticipated social costs shape help-seeking and interpersonal engagement on campus, often discouraging direct disclosure or public support-seeking [60,61].

Importantly, our sample spans ages 17–26, covering late adolescence and emerging adulthood. These developmental periods involve intensive academic/career exploration, role transitions, and reorganizing peer networks while socio-emotional regulation systems continue to mature. Under these conditions, increased sensitivity to exclusion cues and reliance on avoidance strategies may be especially likely to co-occur with withdrawal during these stages.

4.2. Mediating Role of Internet Addiction

Consistent with Hypothesis 4, the results revealed that internet addiction partially mediated the relationship between loneliness and social withdrawal in college students. The findings align with the CIUT, which proposes that individuals turn to online activities to regulate negative affect or compensate for unmet needs—processes especially relevant when offline participation feels risky or unrewarding. Corroborating prior work, lonelier individuals tend to report poorer self-regulation and greater reliance on avoidant coping, including heavy internet use [28,62,63,64]. Features of digital contexts—controllable self-presentation and reduced exposure to face-threatening cues—can render online interaction a functional substitute for in-person contact [31,65], which is salient for students concerned with “face” in collectivist settings. Converging evidence further indicates that elevated internet addiction co-occurs with erosion of offline engagement and impairments in social functioning [30,66,67,68]. Taken together, our data extend CIUT to a late-adolescent and emerging-adult college cohort by showing that the loneliness and social withdrawal link travels, in part, through a technology-related behavioral pathway.

4.3. Moderating Role of Sex

The moderated-mediation analyses further suggest that sex conditions the strength of the path between loneliness and internet addiction: the association is positive for both males and females, but stronger among males. In other words, lonely male students appear especially prone to excessive internet use, which then contributes to withdrawal from offline social life, whereas lonely female students show a weaker tendency to develop addictive internet behaviors. This pattern aligns with meta-analytic findings that the loneliness and internet addiction relationship is weaker in females, implying a more pronounced effect in males [67]. Similarly, other studies have found male students to be at higher risk of problematic internet use, especially in forms like online gaming, whereas females are more prone to compulsive social networking [19,42,43].

These sex differences may reflect divergent psychological mechanisms and motivational drives behind internet use. Males and females tend to utilize the internet to fulfil different psychological needs: females are more likely to use digital platforms to maintain social connections, while males often use them for recreation, achievement, or escape [67,69]. As a result, a lonely female student might turn to social media or online communication to alleviate loneliness. While such usage may become problematic, it still offers a degree of social interaction. Over time, this avoidant, technology-based coping can spiral into addiction, especially if males are less inclined to seek emotional support through interpersonal means. Under lonely states, reduced interpersonal help-seeking among males may coincide with immersive online engagement, which in turn is found alongside reduced offline participation. Although prior research indicates that behavioral subtypes of internet use (e.g., online gaming vs. social networking) differ in prevalence and correlational profiles by sex, our operationalization treated internet-use behavior under internet addiction as a single construct. This approach may obscure behavior-specific pathways linking loneliness to reduced offline participation and may partly account for the observed sex-conditioned effects.

4.4. Practical Contributions

Late adolescence and emerging adulthood constitute a formative period for students’ social and psychological maturation, during which the need for interpersonal connection is pronounced and social-skill development receives heightened attention. However, social withdrawal during this stage may coincide with weaker growth in social skills and with poorer mental-health indicators [70]. Therefore, timely and appropriate adjustments and interventions are necessary to mitigate these risks.

Educational institutions play a critical role in promoting students’ mental health and social well-being. In our data, loneliness is positively associated with social withdrawal. Within this correlational frame, programs that identify students reporting higher loneliness and offer peer-based, connection-oriented activities may help create conditions that are associated with lower loneliness and withdrawal indicators. Research indicates that interventions focusing on enhancing social interactions are effective in mitigating loneliness among students [71]. Peer support groups and structured, skills-focused activities (e.g., communication practice, project-based clubs) provide low-barrier opportunities for in-person engagement and can be implemented without singling out distress. In collectivist contexts where face concerns may elevate help-seeking thresholds, opt-in formats can normalize participation.

This study highlights that internet addiction plays a mediating role in the relationship between loneliness and social withdrawal. Thus, students can adopt alternative, more adaptive coping mechanisms instead of relying on internet addiction to deal with loneliness, thereby potentially reducing social withdrawal tendencies. From a family perspective, parental awareness and involvement are crucial in identifying and addressing problematic internet use. Studies have shown that family-based interventions can effectively reduce internet addiction behavior [72]. Educational workshops aimed at parents can equip them with the tools to recognize signs of internet addiction and implement supportive measures. Encouraging open communication within families about online activities can also foster a supportive environment that may reduce the adverse effects of loneliness and social withdrawal.

Sex is also an important factor to consider. For male students, who appear more vulnerable to using the internet as an unhealthy coping mechanism, programs might focus on developing alternative strategies for dealing with loneliness. For example, encouraging help-seeking, fostering offline group activities, and teaching emotion-regulation skills that reduce the urge to self-isolate online [41].

4.5. Limitations and Future Directions

This study advances understanding of the associations among loneliness, internet addiction, and social withdrawal in late adolescence and emerging adulthood, but several limitations qualify interpretation and generalizability.

The sample was recruited from four colleges (public and private) located in Guangdong, which may restrict external validity. Given China’s size and regional diversity, future research should, where feasible, adopt probability-based sampling and consider post-stratification/weighting to improve population coverage. The sample was also skewed toward females (68.4%) and first-year students (68.4%), reflecting, in part, the sex composition of some Chinese colleges and the greater availability of first-year cohorts; such disproportions may shape observed associations. Subsequent studies should set balanced recruitment targets and use multi-group/stratified analyses to assess heterogeneity and reduce composition bias.

Our directional specification (Loneliness → internet addiction → Social withdrawal) was theory-guided, drawing on Cacioppo’s ETL and CIUT. Yet the cross-sectional design limits inference to covariation, not causation, and cannot rule out bidirectional processes. To formally test directionality and mediation, we recommend adopting experimental designs to first test the association between loneliness and social withdrawal, and then the causal nature of the mediating role of internet addiction. Participants should first be randomly assigned to social inclusion or exclusion conditions, with proximal social-withdrawal outcomes assessed via choice of solitary versus group tasks or latency to opt into interaction. Subsequently, a 2 × 2 experimental design should be employed, crossing social inclusion vs. exclusion with internet-addiction status (addicted vs. non-addicted), to assess whether the impact of loneliness on social withdrawal varies as a function of addiction status.

5. Conclusions

This study reveals that internet addiction mediates the link between loneliness and social withdrawal in Chinese college students, emphasizing its role in shaping social behaviors. Educational authorities should integrate loneliness and internet addiction into the mental health screening system for college students and develop targeted intervention plans to promote students’ social engagement and psychological well-being.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.Z. and M.S.A.; methodology, X.Z., M.S.A. and S.S.; software, X.Z. and H.Y.; validation, H.Y.; investigation, X.Z.; data curation, S.S. and H.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, X.Z. and M.S.A.; writing—review and editing, X.Z., S.S. and M.S.A.; supervision, M.S.A. and S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Review Board of the Educational Planning and Research Division, Ministry of Education Malaysia (protocol code: KPM.600-3/2/3-eras (17140) and date of approval: 12 August 2023.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to sincerely express their gratitude to the editors, anonymous reviewers, and study participants for their valuable feedback, suggestions, and contributions. Any remaining errors are solely the authors’ responsibility.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ETL | Evolutionary Theory of Loneliness |

| CIUT | Compensatory Internet Use Theory |

| CMB | Common Method Bias |

| CFA | Confirmatory Factor Analysis |

| SEM | Structural Equation Modeling |

| AVE | Average Variance Extracted |

| CR | Composite Reliability |

References

- Fan, Z.; Shi, X.; Yang, S.; Sun, Y.; Chen, R. Reliability and Validity Evaluation of the Stigma of Loneliness Scale in Chinese College Students. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trucharte, A.; Calderón, L.; Cerezo, E.; Contreras, A.; Peinado, V.; Valiente, C. Three-Item Loneliness Scale: Psychometric Properties and Normative Data of the Spanish Version. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 7466–7474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yung, S.T.; Chen, Y.; Zawadzki, M.J. Loneliness and Psychological Distress in Everyday Life among Latinx College Students. J. Am. Coll. Health 2023, 71, 1407–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gritsenko, V.; Skugarevsky, O.; Konstantinov, V.; Khamenka, N.; Marinova, T.; Reznik, A.; Isralowitz, R. COVID 19 Fear, Stress, Anxiety, and Substance Use Among Russian and Belarusian University Students. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2021, 19, 2362–2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonnie, R.J.; Backes, E.P. (Eds.) The Promise of Adolescence; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; ISBN 978-0-309-49008-5. [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer, S.M.; Azzopardi, P.S.; Wickremarathne, D.; Patton, G.C. The Age of Adolescence. Lancet Child. Adolesc. Health 2018, 2, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American College Health Association. National College Health Assessment II: Reference Group Executive Summary Spring 2019; American College Health Association: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Groarke, J.M.; Berry, E.; Graham-Wisener, L.; McKenna-Plumley, P.E.; McGlinchey, E.; Armour, C.; Murakami, M. Loneliness in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic: Cross-sectional results from the COVID-19 Psychological Wellbeing Study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0239698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesen, H.; Konno, Y.; Tateishi, S.; Hino, A.; Tsuji, M.; Ogami, A.; Nagata, M.; Muramatsu, K.; Yoshimura, R.; Fujino, Y. Association Between Loneliness and Sleep-Related Problems Among Japanese Workers During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 828650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muris, P.; Ollendick, T.H. Contemporary Hermits: A Developmental Psychopathology Account of Extreme Social Withdrawal (Hikikomori) in Young People. Clin. Child. Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2023, 26, 459–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirwan, E.M.; Burns, A.; O’Súilleabháin, P.S.; Summerville, S.; McGeehan, M.; McMahon, J.; Gowda, A.; Creaven, A.-M. Loneliness in Emerging Adulthood: A Scoping Review. Adolesc. Res. Rev. 2025, 10, 47–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, K.H.; Coplan, R.J.; Bowker, J.C. Social Withdrawal in Childhood. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2009, 60, 141–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, K.H.; Chronis-Tuscano, A. Perspectives on Social Withdrawal in Childhood: Past, Present, and Prospects. Child. Dev. Perspect. 2021, 15, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, A.F.W.; Chou, T.L.; Catmur, C.; Lau, J.Y.F. Loneliness and Social Disconnectedness in Pathological Social Withdrawal. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2020, 163, 110092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkley, L.C.; Thisted, R.A.; Cacioppo, J.T. Loneliness Predicts Reduced Physical Activity: Cross-Sectional & Longitudinal Analyses. Health Psychol. 2009, 28, 354–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arpin, S.N.; Mohr, C.D. Transient Loneliness and the Perceived Provision and Receipt of Capitalization Support Within Event-Disclosure Interactions. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2019, 45, 240–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacioppo, J.T.; Cacioppo, S.; Boomsma, D.I. Evolutionary Mechanisms for Loneliness. Cogn. Emot. 2014, 28, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newall, N.E.; Chipperfield, J.G.; Clifton, R.A.; Perry, R.P.; Swift, A.U.; Ruthig, J.C. Causal Beliefs, Social Participation, and Loneliness among Older Adults: A Longitudinal Study. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2009, 26, 273–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Fernández, M.; Borda-Mas, M.; Mora-Merchán, J. Problematic Internet Use by University Students and Associated Predictive Factors: A Systematic Review. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2023, 139, 107532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavez-Yacolca, D.R.; Castro-Champión, R.B.; Cisneros-Gonzales, N.M.; Cunza-Aranzábal, D.F.; Morales-García, M.; Abanto-Ramírez, C.D. Relationship between Academic Procrastination and Internet Addiction in Peruvian University Students: The Mediating Role of Academic Self-Efficacy. Front. Psychol. 2025, 15, 1454234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Ye, Y.; Li, C. Link between Internet Addiction and Depression and Roles of Social Withdrawal and School Belonging. Child. Fam. Soc. Work. 2024, 29, 920–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, N.; Zhang, X. Bullying Victimization and Quality of Life among Chinese Adolescents: An Integrative Analysis of Internet Addiction and Social Withdrawal. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Wu, P.; Luo, Y.; He, X.; Fu, L.; Liu, H.; Lin, F.; Xu, Q.; Wu, X. Internet Addiction, Loneliness, and Academic Burnout among Chinese College Students: A Mediation Model. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1176596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rennoch, G.; Schlomann, A.; Zank, S. The Relationship Between Internet Use for Social Purposes, Loneliness, and Depressive Symptoms Among the Oldest Old. Res. Aging 2023, 45, 630–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Z.; Kou, Y. Effects of Loneliness on Short Video Addiction among College Students: The Chain Mediating Role of Social Support and Physical Activity. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1484117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Li, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, T.; Luo, J. The Role of Loneliness and Learning Burnout in the Regulation of Physical Exercise on Internet Addiction in Chinese College Students. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kardefelt-Winther, D. A Conceptual and Methodological Critique of Internet Addiction Research: Towards a Model of Compensatory Internet Use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 31, 351–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H. Psychological Issues and Problematic Use of Smartphone: ADHD’s Moderating Role in the Associations among Loneliness, Need for Social Assurance, Need for Immediate Connection, and Problematic Use of Smartphone. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 80, 390–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meynadier, J.; Malouff, J.M.; Schutte, N.S.; Loi, N.M.; Griffiths, M.D. Relationships Between Social Media Addiction, Social Media Use Metacognitions, Depression, Anxiety, Fear of Missing Out, Loneliness, and Mindfulness. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2025, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Feng, R.; Zhang, J. The Relationship between Loneliness and Problematic Social Media Usage in Chinese University Students: A Longitudinal Study. BMC Psychol. 2024, 12, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenaza-Urquijo, E.M.; Boyle, R.; Casaletto, K.; Anstey, K.J.; Vila-Castelar, C.; Colverson, A.; Palpatzis, E.; Eissman, J.M.; Kheng Siang Ng, T.; Raghavan, S.; et al. Sex and Gender Differences in Cognitive Resilience to Aging and Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2024, 20, 5695–5719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speechley, M.; Stuart, J.; Modecki, K.L. Diverse Gender Identity Development: A Qualitative Synthesis and Development of a New Contemporary Framework. Sex Roles 2024, 90, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Ke, S.; Lian, R.; Li, D. The Association between Interpersonal Competence and Meaning in Life: Roles of Loneliness and Grade. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2020, 36, 576–583. [Google Scholar]

- Leich, M.; Guse, J.; Bergelt, C. Loneliness and Mental Burden among German Medical Students during the Fading COVID-19 Pandemic: A Mixed-Methods Approach. Front. Psychol. 2025, 16, 1526960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen-Mansfield, J.; Hazan, H.; Lerman, Y.; Shalom, V. Correlates and Predictors of Loneliness in Older-Adults: A Review of Quantitative Results Informed by Qualitative Insights. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2016, 28, 557–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beutel, M.E.; Klein, E.M.; Brähler, E.; Reiner, I.; Jünger, C.; Michal, M.; Wiltink, J.; Wild, P.S.; Münzel, T.; Lackner, K.J.; et al. Loneliness in the General Population: Prevalence, Determinants and Relations to Mental Health. BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasgaard, M.; Friis, K.; Shevlin, M. “Where Are All the Lonely People?” A Population-Based Study of High-Risk Groups across the Life Span. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2016, 51, 1373–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltzer, K.; Pengpid, S. Loneliness Correlates and Associations with Health Variables in the General Population in Indonesia. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2019, 13, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto, M.; Victor, C.; Hammond, C.; Eccles, A.; Richins, M.T.; Qualter, P. Loneliness around the World: Age, Gender, and Cultural Differences in Loneliness. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2021, 169, 110066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.; Wang, T.; Sun, Y.; Zhai, F. The Influence of Physical Activity on Internet Addiction among Chinese College Students: The Mediating Role of Self-Esteem and the Moderating Role of Gender. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, X.; Ou, Y.; Ding, Y.; Yan, H.; Chen, J.; Zhao, J.; Guo, W. Associations Between Internet Addiction and Gender, Anxiety, Coping Styles and Acceptance in University Freshmen in South China. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 558080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varchetta, M.; Tagliaferri, G.; Mari, E.; Quaglieri, A.; Cricenti, C.; Giannini, A.M.; Martí-Vilar, M. Exploring Gender Differences in Internet Addiction and Psychological Factors: A Study in a Spanish Sample. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-Y.; Chou, W.-H. Smartphone Addiction, Gender and Interpersonal Attachment: A Cross-Sectional Analytical Survey in Taiwan. Digit. Health 2023, 9, 20552076231177134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, P.G. Methods for the Detection of Carelessly Invalid Responses in Survey Data. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2016, 66, 4–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, R.; Du, J. Reliability and Validity of the 6-Item UCLA Loneliness Scale (ULS-6) for Application in Adults. J. South. Med. Univ. 2023, 43, 900–905. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Weng, L.; Su, Y.; Wu, H.; Yang, P. A Study on the Development and Psychometric Properties of the Chinese Internet Addiction Scale. Chin. J. Psychol. 2003, 5, 279–294. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Y.; Fan, F.M. A Study on the Internet Dependence of College Students: The Revising and Applying of a Measurement. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2005, 4, 99–104. [Google Scholar]

- King, B.S.; Beehr, T.A. Working with the Stress of Errors: Error Management Strategies as Coping. Int. J. Stress. Manag. 2017, 24, 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Chen, X.; Liu, L.; Sun, C. The Relationship between Social Withdrawal and Problematic Social Media Use in Chinese College Students: A Chain Mediation of Alexithymia and Negative Body Image. BMC Psychol. 2024, 12, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif-Nia, H.; Froelicher, E.S.; Shafighi, A.H.; Osborne, J.W.; Fatehi, R.; Nowrozi, P.; Mohammadi, B. The Persian Version of the Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire among Iranian Post-Surgery Patients: A Translation and Psychometrics. BMC Psychol. 2024, 12, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hair, J.F.; Lds Gabriel, M.; da Silva, D.; Braga Junior, S. Development and Validation of Attitudes Measurement Scales: Fundamental and Practical Aspects. RAUSP Manag. J. 2019, 54, 490–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonaka, S.; Kubo, H.; Takeda, T.; Sakai, M. Functioning, Disability, and Health of Individuals with Hikikomori (Prolonged Social Withdrawal) and Their Families: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Case-Control Studies. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2025, 71, 622–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verhagen, M.; Derks, M.; Roelofs, K.; Maciejewski, D. Behavioral Inhibition, Negative Parenting, and Social Withdrawal: Longitudinal Associations with Loneliness during Early, Middle, and Late Adolescence. Child. Dev. 2023, 94, 512–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.H.; Luchetti, M.; Sesker, A.; Aschwanden, D.; Sutin, A.; Terracciano, A. Self- and Informant-Reported Loneliness and Cognitive Function: Evidence From Three HCAP Studies. Innov. Aging 2021, 5, 1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aditya, B.; Neena, K. Theoretical Approach to Loneliness: A Cognitive Perspective. Eur. Acad. Res. 2023, 10, 4090–4094. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, W. A Review of the Effects and Interventions of Loneliness. Adv. Psychol. 2019, 9, 585–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floyd, K.; Woo, N.; Custer, B.; Dinsmore, D.; Duncan, K.; Maré, J. Examining the Social Signaling and Person Perception Functions of Loneliness. OBM Neurobiol. 2022, 6, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, K. Beliefs in Chinese Culture; University of Hong Kong: Hong Kong, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, W.; Hall, B.J. Help-Seeking Preferences among Chinese College Students Exposed to a Natural Disaster: A Person-Centered Approach. Eur. J. Psychotraumatology 2020, 11, 1761621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, X.; Wong, J.P.-H.; Huang, S.; Fu, Y.; Gong, X.; Zhang, L.; Hilario, C.; Fung, K.P.-L.; Yu, M.; Poon, M.K.-L.; et al. Chinese University Students’ Perspectives on Help-Seeking and Mental Health Counseling. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H. Longitudinal Associations Among Psychological Issues and Problematic Use of Smartphones. J. Media Psychol. 2019, 31, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.F.; Gao, F.Q.; Geng, J.Y.; Wang, Y.M.; Han, L. Social Avoidance and Distress and Mobile Phone Addiction: A Multiple Mediating Model. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2018, 26, 494–497. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Che, W.B.; Li, B. A Research on College Students’ Coping Styles of Psychological Stress. Psychol. Sci. 2005, 28, 36–41. [Google Scholar]

- Li, R.; Fu, W.; Liang, Y.; Huang, S.; Xu, M.; Tu, R. Exploring the Relationship between Resilience and Internet Addiction in Chinese College Students: The Mediating Roles of Life Satisfaction and Loneliness. Acta Psychol. 2024, 248, 104405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tateno, M.; Teo, A.R.; Ukai, W.; Kanazawa, J.; Katsuki, R.; Kubo, H.; Kato, T.A. Internet Addiction, Smartphone Addiction, and Hikikomori Trait in Japanese Young Adult: Social Isolation and Social Network. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zeng, Y. Relationship between Loneliness and Internet Addiction: A Meta-Analysis. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Fan, D.; Shao, Y. Social Withdrawal (Hikikomori) Conditions in China: A Cross-Sectional Online Survey. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 826945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinaldi, M.R.; Aini, L.N.; Kurniawan, A.P. Gender Differences in Online Behavior: Exploring the Moderating Effect on Loneliness and Cyberslacking among University Students. Psympathic J. Ilm. Psikol. 2024, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerbara, L.; Ciancimino, G.; Corsetti, G.; Tintori, A. Self-Isolation of Adolescents after COVID-19 Pandemic between Social Withdrawal and Hikikomori Risk in Italy. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eccles, A.M.; Qualter, P. Review: Alleviating Loneliness in Young People—A Meta-analysis of Interventions. Child. Adolesc. Ment. Health 2021, 26, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, X. Internet Addiction among College Students in China and Its Underlying Causes. Sci. Insights Educ. Front. 2023, 16, 2457–2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).