Tuning of Thermally Activated Delayed Fluorescence Properties in the N,N-Diphenylaminophenyl–Phenylene–Quinoxaline D–π–A System

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. General Information

2.2. Photophysical Measurements

2.3. Synthesis

- 4’-Bromo-2′,5′-dimethyl-N,N-diphenyl-[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-amine (5-Me)

- N,N-Diphenyl-4′-(4,4,5,5-tetramethyl-1,3,2-dioxaborolan-2-yl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-amine (6-H)

- 2′,5′-Dimethyl-N,N-diphenyl-4′-(4,4,5,5-tetramethyl-1,3,2-dioxaborolan-2-yl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-amine (6-Me)

- 4′-(6,7-Difluoro-3-(trifluoromethyl)quinoxalin-2-yl)-N,N-diphenyl-[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-amine (1-H)

- 4′-(6,7-Difluoro-3-(trifluoromethyl)quinoxalin-2-yl)-2′,5′-Dimethyl-N,N-diphenyl-[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-amine (1-Me)

3. Results and Discussion

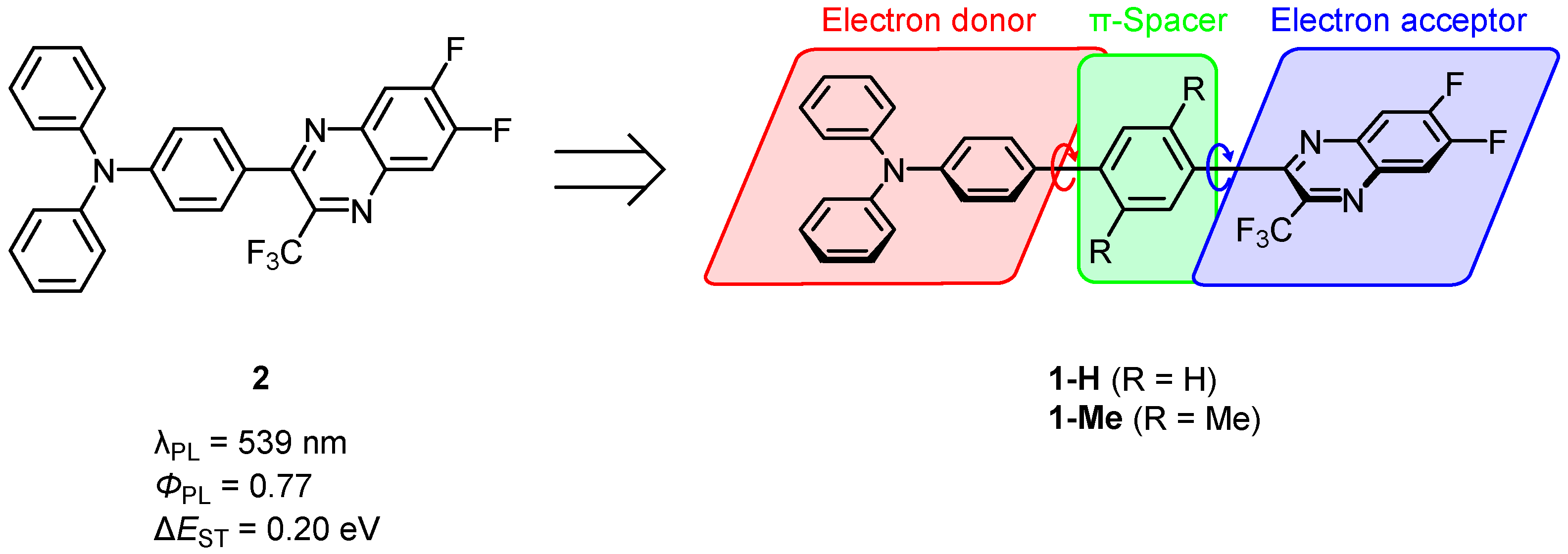

3.1. Synthesis of 1-H and 1-Me

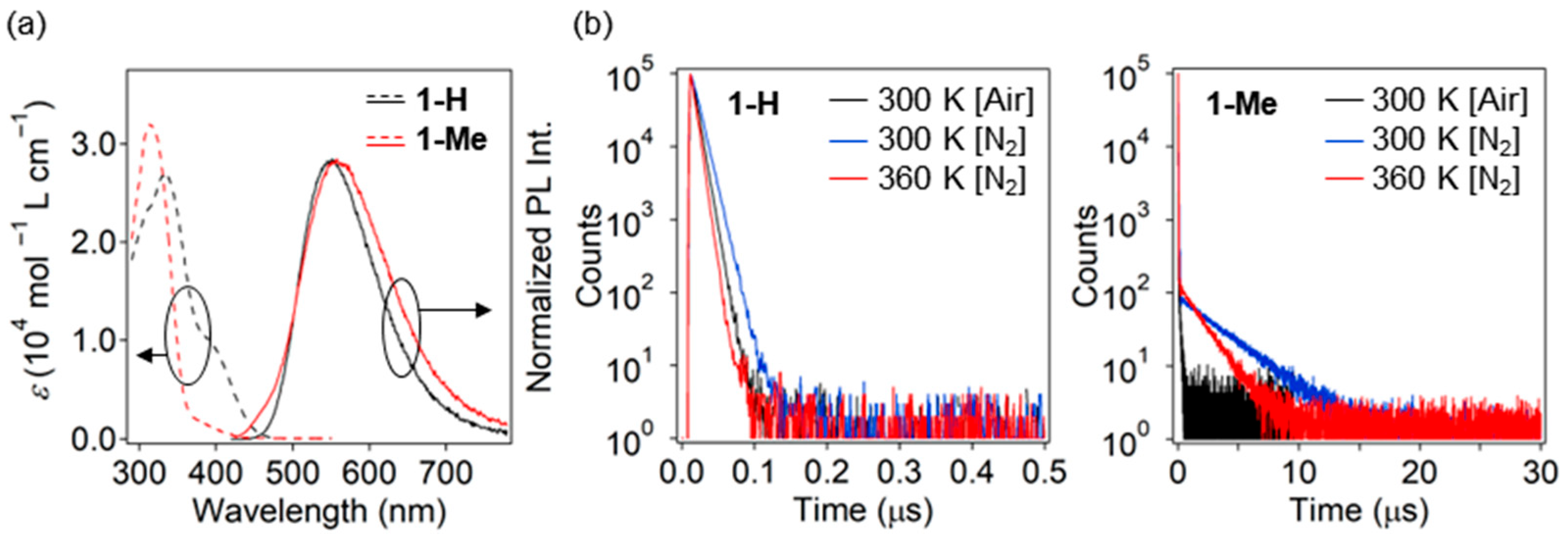

3.2. Photophysical Properties in Toluene

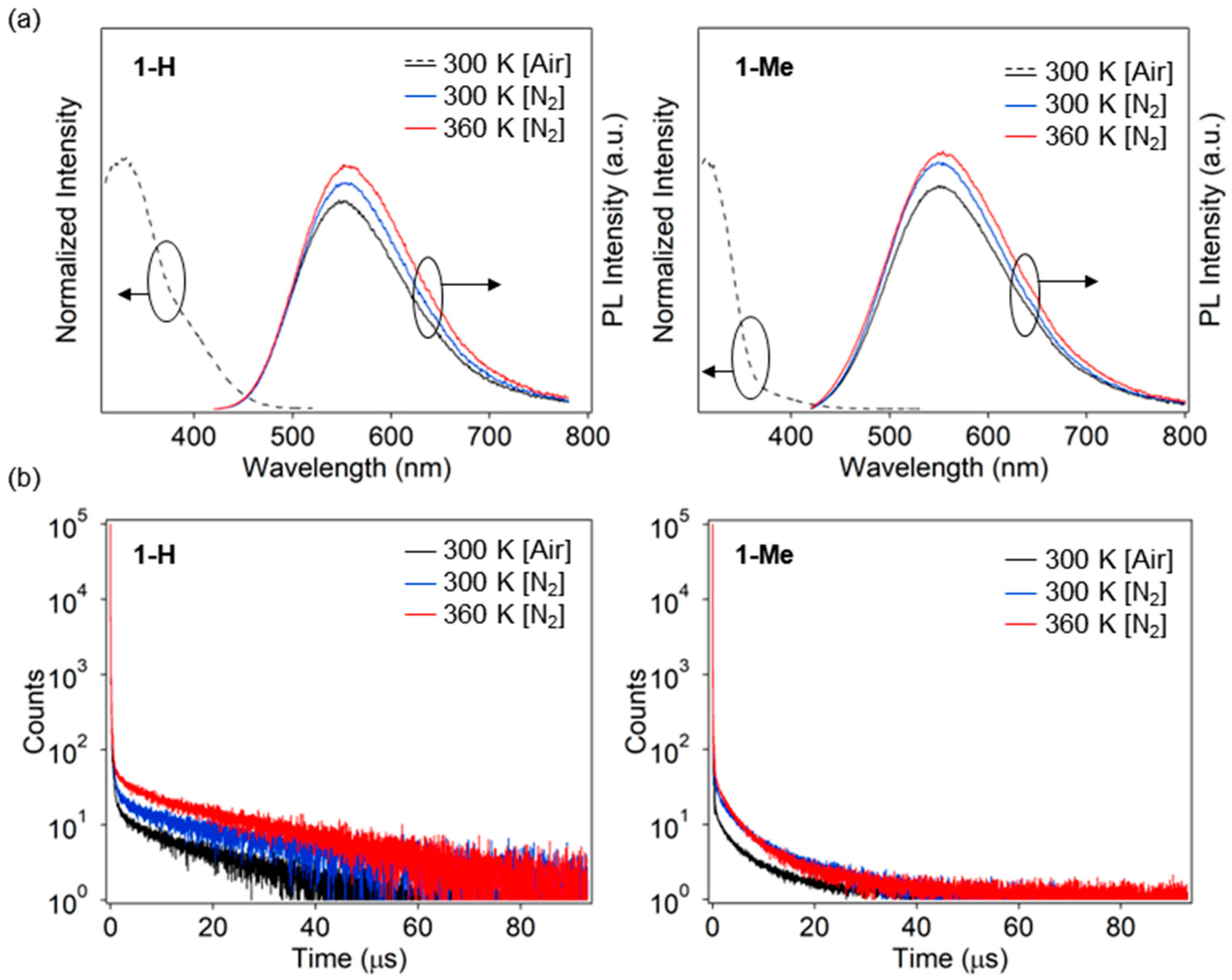

3.3. Photophysical Properties in PMMA Film

3.4. Estimation of ΔEST

3.5. Photophysical Parameters

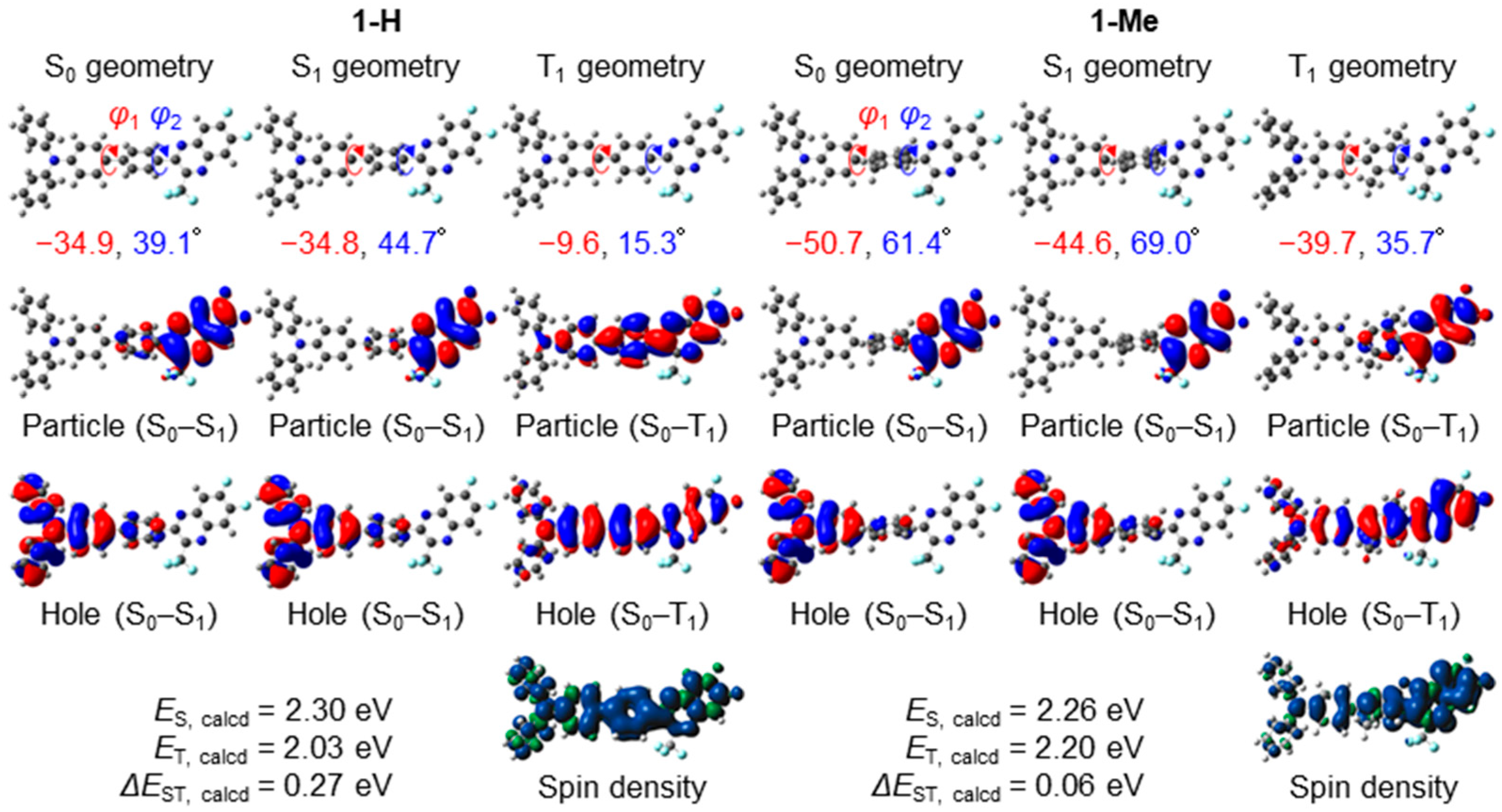

3.6. Theoretical Calculations

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tang, C.W.; VanSlyke, S.A. Organic electroluminescent diodes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1987, 51, 913–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.W.; VanSlyke, S.A.; Chen, C.H. Electroluminescence of doped organic thin films. J. Appl. Phys. 1989, 65, 3610–3616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, S.A.; Wallraff, G.M.; Chen, J.P.; Zhang, W.; Bozano, L.D.; Carter, K.R.; Salem, J.R.; Villa, R.; Scott, J.C. Stable and Efficient Fluorescent Red and Green Dyes for External and Internal Conversion of Blue OLED Emission. Chem. Mater. 2003, 15, 2305–2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheats, J.R.; Antoniadis, H.; Hueschen, M.; Leonard, W.; Miller, J.; Moon, R.; Roitman, D.; Stocking, A. Organic Electroluminescent Devices. Science 1996, 273, 884–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farinola, G.M.; Ragni, R. Electroluminescent materials for white organic light emitting diodes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 3467–3482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hung, L.S.; Chen, C.H. Recent progress of molecular organic electroluminescent materials and devices. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2002, 39, 143–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitschke, U.; Bäuerle, P. The electroluminescence of organic materials. J. Mater. Chem. 2000, 10, 1471–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Ho, C.-L.; Wang, L.; Wong, W.-Y. Single-Molecular White-Light Emitters and Their Potential WOLED Applications. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 1903269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.-T.; Yen, C.-K.; Yang, W.-P.; Chen, H.-H.; Liao, C.-H.; Tsai, C.-H.; Chen, C.H. Efficient Green Coumarin Dopants for Organic Light-Emitting Devices. Org. Lett. 2004, 6, 1241–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, K.R.J.; Lin, J.T.; Velusamy, M.; Tao, Y.-T.; Chuen, C.-H. Color Tuning in Benzo[1,2,5]thiadiazole-Based Small Molecules by Amino Conjugation/Deconjugation: Bright Red-Light-Emitting Diodes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2004, 14, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chepelianskii, A.; Gao, F.; Greenham, N.C. Control of exciton spin statistics through spin polarization in organic optoelectronic devices. Nat. Commun. 2012, 3, 1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uoyama, H.; Goushi, K.; Shizu, K.; Nomura, H.; Adachi, C. Highly efficient organic light-emitting diodes from delayed fluorescence. Nature 2012, 492, 234–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaji, H.; Suzuki, H.; Fukushima, T.; Shizu, K.; Suzuki, K.; Kubo, S.; Komino, T.; Oiwa, H.; Suzuki, F.; Wakamiya, A.; et al. Purely organic electroluminescent material realizing 100% conversion from electricity to light. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatakeyama, T.; Shiren, K.; Nakajima, K.; Nomura, S.; Nakatsuka, S.; Kinoshita, K.; Ni, J.; Ono, Y.; Ikuta, T. Ultrapure Blue Thermally Activated Delayed Fluorescence Molecules: Efficient HOMO–LUMO Separation by the Multiple Resonance Effect. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 2777–2781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarma, M.; Wong, K.-T. Exciplex: An Intermolecular Charge-Transfer Approach for TADF. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 19279–19304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Wang, H.; Xie, Z.; Shen, M.; Huang, R.; Miao, Y.; Liu, G.; Yu, T.; Huang, W. NIR TADF emitters and OLEDs: Challenges, progress, and perspectives. Chem. Sci. 2022, 13, 8906–8923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, T.; Jiang, W.; Duan, L. Recent progress in solution processable TADF materials for organic light-emitting diodes. J. Mater. Chem. C 2018, 6, 5577–5596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, H.; Shizu, K.; Miyazaki, H.; Adachi, C. Efficient green thermally activated delayed fluorescence (TADF) from a phenoxazine-triphenyltriazine (PXZ-TRZ) derivative. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 11392–11394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stachelek, P.; Ward, J.S.; dos Santos, P.L.; Danos, A.; Colella, M.; Haase, N.; Raynes, S.J.; Batsanov, A.S.; Bryce, M.R.; Monkman, A.P. Molecular Design Strategies for Color Tuning of Blue TADF Emitters. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 27125–27133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zassowski, P.; Ledwon, P.; Kurowska, A.; Herman, A.P.; Lapkowski, M.; Cherpak, V.; Hotra, Z.; Turyk, P.; Ivaniuk, K.; Stakhira, P.; et al. 1,3,5-Triazine and carbazole derivatives for OLED applications. Dyes Pigm. 2018, 149, 804–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, C. Third-generation organic electroluminescence materials. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2014, 53, 060101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakanotani, H.; Tsuchiya, Y.; Adachi, C. Thermally-activated Delayed Fluorescence for Light-emitting Devices. Chem. Lett. 2021, 50, 938–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Zhang, Z.; Liy, Y.; Deng, Z.; Luo, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Tang, B.Z. Delayed Fluorescence Materials: Mechanism, Design, and Bioapplication. J. Phys. Chem. C 2024, 128, 15763–15777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Zheng, L.; Yuan, J.; An, Z.; Chen, R.; Tao, Y.; Li, H.; Xie, X.; Huang, W. Understanding the Control of Singlet-Triplet Splitting for Organic Exciton Manipulating: A Combined Theoretical and Experimental Approach. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 10923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, H.; Shizu, K.; Nakanotani, H.; Adachi, C. Dual Intramolecular Charge-Transfer Fluorescence Derived from a Phenothiazine-Triphenyltriazine Derivative. J. Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118, 15985–15994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Huang, R.; Batsanov, A.S.; Pander, P.; Hsu, Y.-T.; Chi, Z.; Dias, F.B.; Bryce, M.R. Intramolecular Charge Transfer Controls Switching Between Room Temperature Phosphorescence and Thermally Activated Delayed Fluorescence. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 16407–16411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Issac, J.; Ravi, S.; Karthikeyan, S.; Periyasami, G.; Moon, D.; Anthony, S.P.; Madhu, V. Substituent Controlled Tunable Fluorescence from Green to Red and pH Stimuli-Induced Reversible Fluorescence Switching in Triphenylamine–Quinoxaline Derivatives. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2024, 13, e202400282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosokai, T.; Matsuzaki, H.; Nakanotani, H.; Tokumaru, K.; Tsutsui, T.; Furube, A.; Nasu, K.; Nomura, H.; Yahiro, M.; Adachi, C. Evidence and mechanism of efficient thermally activated delayed fluorescence promoted by delocalized excited states. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1603282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pershin, A.; Hall, D.; Lemaur, V.; Sancho-Garcia, J.-C.; Muccioli, L.; Zysman-Colman, E.; Beljonne, D.; Olivier, Y. Highly emissive excitons with reduced exchange energy in thermally activated delayed fluorescent molecules. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaoka, M.; Ueda, K.; Chihara, H.; Suzuki, N.; Kodama, S.; Maeda, T.; Yagi, S. Photo- and Electroluminescence of N,N-Diphenylaminophenyl–Quinoxaline Donor–Acceptor-Type Dyes: Electronic Impacts of Electron-Withdrawing Ability of the Acceptor Unit. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2025, 14, e00364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.-J.; Ahn, M.; Shim, J.H.; Wee, K.-R. Terphenyl backbone-based donor–π–acceptor dyads: Geometric isomer effects on intramolecular charge transfer. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2020, 22, 3370–3378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keruckiene, R.; Vaitusionak, A.A.; Hulnik, M.I.; Berezianko, I.A.; Gudeika, D.; Macionis, S.; Mahmoudi, M.; Volyniuk, D.; Valverde, D.; Olivier, Y.; et al. Is a small singlet–triplet energy gap a guarantee of TADF performance in MR-TADF compounds? Impact of the triplet manifold energy splitting. J. Mater. Chem. C 2024, 12, 3450–3464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méhes, G.; Nomura, H.; Zhang, Q.; Nakagawa, T.; Adachi, C. Enhanced Electroluminescence Efficiency in a Spiro-Acridine Derivative through Thermally Activated Delayed Fluorescence. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 11311–11315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Kuwabara, H.; Potscavage, W.J., Jr.; Huang, S.; Hatae, Y.; Shibata, T.; Adachi, C. Anthraquinone-Based Intramolecular Charge-Transfer Compounds: Computational Molecular Design, Thermally Activated Delayed Fluorescence, and Highly Efficient Red Electroluminescence. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 18070–18081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.-L.; Huang, M.-J.; Lin, C.-C.; Huang, P.-Y.; Chou, T.-Y.; Chen-Cheng, R.-W.; Lin, H.-W.; Liu, R.-S.; Cheng, C.-H. Diboron compound-based organic light-emitting diodes with high efficiency and reduced efficiency roll-off. Nat. Photonics 2018, 12, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goushi, K.; Yoshida, K.; Sato, K.; Adachi, C. Organic light-emitting diodes employing efficient reverse intersystem crossing for triplet-to-singlet state conversion. Nat. Photonics 2012, 6, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.A.; Nakatsuji, H.; et al. Gaussian 09, Revision A.01; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, T.; Chen, F. Multiwfn: A Multifunctional Wavefunction Analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 2012, 33, 580–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T. A comprehensive electron wavefunction analysis toolbox for chemists, Multiwfn. J. Chem. Phys. 2024, 161, 082503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, B.; Liu, M.; Li, Y.; Pan, Y.; Yang, B. Effect of cyano substitution in TADF molecules on luminescence properties: A theoretical study. Chem. Phys. 2023, 575, 112080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, S.; Wang, S.; Xu, X.; Yang, Y.; Lv, J.; Ding, J.; Wang, L.; Jing, X.; Wang, F. Bipolar Poly(arylene phosphine oxide) Hosts with Widely Tunable Triplet Energy Levels for High-Efficiency Blue, Green, and Red Thermally Activated Delayed Fluorescence Polymer Light-Emitting Diodes. Macromolecules 2019, 52, 3394–3403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Compd. | λabs (nm) [εabs (mol−1 L cm−1)] | λPL (nm) | ΦPL [Air/N2] | CIE 2 (x, y) | τ1 (ns) [A1 (%)]/τ2 (μs) [A2 (%)] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 300 K, Air | 300 K, N2 | 360 K, N2 | |||||

| 1-H | 334 [26,900], 400 [9000] 1 | 552 | 0.24/0.55 | (0.41, 0.54) | 7.5 [100]/- | 10 [100]/- | 6.1 [100]/- |

| 1-Me | 313 [32,0], 386 [1500] 1 | 558 | 0.06/0.21 | (0.42, 0.50) | 8.0 [96.7]/0.15 [3.3] | 24 [88.7]/3.7 [11.3] | 17 [87.5]/1.9 [12.5] |

| Compd. | Condition | λEX (nm) | λPL (nm) | ΦPL | CIE 3 (x, y) | τ1 (ns) [A1 (%)] | τ2 (ns) [A2 (%)] | τ3 (μs) [A3 (%)] | τ4 (μs) [A4 (%)] | τp (ns) 4 [Ap%] 5 | τd (μs) 6 [Ad%] 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-H | 300 K, Air | 326, 403 1 | 547 | 0.38 | (0.39, 0.50) | 16 [79.5] | 180 [8.0] | 2.0 [1.0] | 21 [11.5] | - | - |

| 300 K, N2 | - | 555 | 0.55 | - | 16 [68.3] | 200 [7.7] | 2.3 [2.2] | 32 [21.9] | 35 [76.0] | 29 [24.0] | |

| 360 K, N2 | - | 551 | 0.61 2 | - | 13 [53.9] | 150 [8.0] | 2.2 [3.1] | 29 [34.9] | 26 [61.9] | 27 [38.1] | |

| 1-Me | 300 K, Air | 313, 394 1 | 550 | 0.23 | (0.38, 0.49) | 3.0 [69.7] | 60 [13.9] | 1.8 [5.0] | 10 [11.4] | - | - |

| 300 K, N2 | - | 554 | 0.46 | - | 3.0 [51.0] | 70 [19.0] | 3.4 [12.7] | 17 [17.3] | 21 [70.0] | 11 [30.0] | |

| 360 K, N2 | - | 554 | 0.49 2 | - | 2.0 [41.3] | 60 [19.8] | 3.1 [21.7] | 16 [17.2] | 21 [61.1] | 8.8 [38.9] |

| Compd. | λflu, onset (nm) | λphos, onset (nm) | ES (eV) 1 | ET (eV) 2 | ΔEST (eV) 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-H | 444 | 486 | 2.79 | 2.55 | 0.24 |

| 1-Me | 463 | 475 | 2.68 | 2.61 | 0.07 |

| Compd. | Φp | Φd | kp (107 s−1) | kd (104 s−1) | ΦIC | ΦISC | kIC (106 s−1) | kISC (106 s−1) | kRISC (104 s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-H | 0.42 | 0.13 | 1.2 | 1.9 | 0.34 | 0.24 | 9.8 | 6.9 | 1.0 |

| 1-Me | 0.32 | 0.14 | 1.5 | 4.2 | 0.38 | 0.30 | 18 | 14 | 1.9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nagaoka, M.; Chihara, H.; Kodama, S.; Maeda, T.; Kato, S.-i.; Yagi, S. Tuning of Thermally Activated Delayed Fluorescence Properties in the N,N-Diphenylaminophenyl–Phenylene–Quinoxaline D–π–A System. Compounds 2025, 5, 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/compounds5040059

Nagaoka M, Chihara H, Kodama S, Maeda T, Kato S-i, Yagi S. Tuning of Thermally Activated Delayed Fluorescence Properties in the N,N-Diphenylaminophenyl–Phenylene–Quinoxaline D–π–A System. Compounds. 2025; 5(4):59. https://doi.org/10.3390/compounds5040059

Chicago/Turabian StyleNagaoka, Masaki, Hiroaki Chihara, Shintaro Kodama, Takeshi Maeda, Shin-ichiro Kato, and Shigeyuki Yagi. 2025. "Tuning of Thermally Activated Delayed Fluorescence Properties in the N,N-Diphenylaminophenyl–Phenylene–Quinoxaline D–π–A System" Compounds 5, no. 4: 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/compounds5040059

APA StyleNagaoka, M., Chihara, H., Kodama, S., Maeda, T., Kato, S.-i., & Yagi, S. (2025). Tuning of Thermally Activated Delayed Fluorescence Properties in the N,N-Diphenylaminophenyl–Phenylene–Quinoxaline D–π–A System. Compounds, 5(4), 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/compounds5040059