Human Anisakidosis with Intraoral Localization: A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

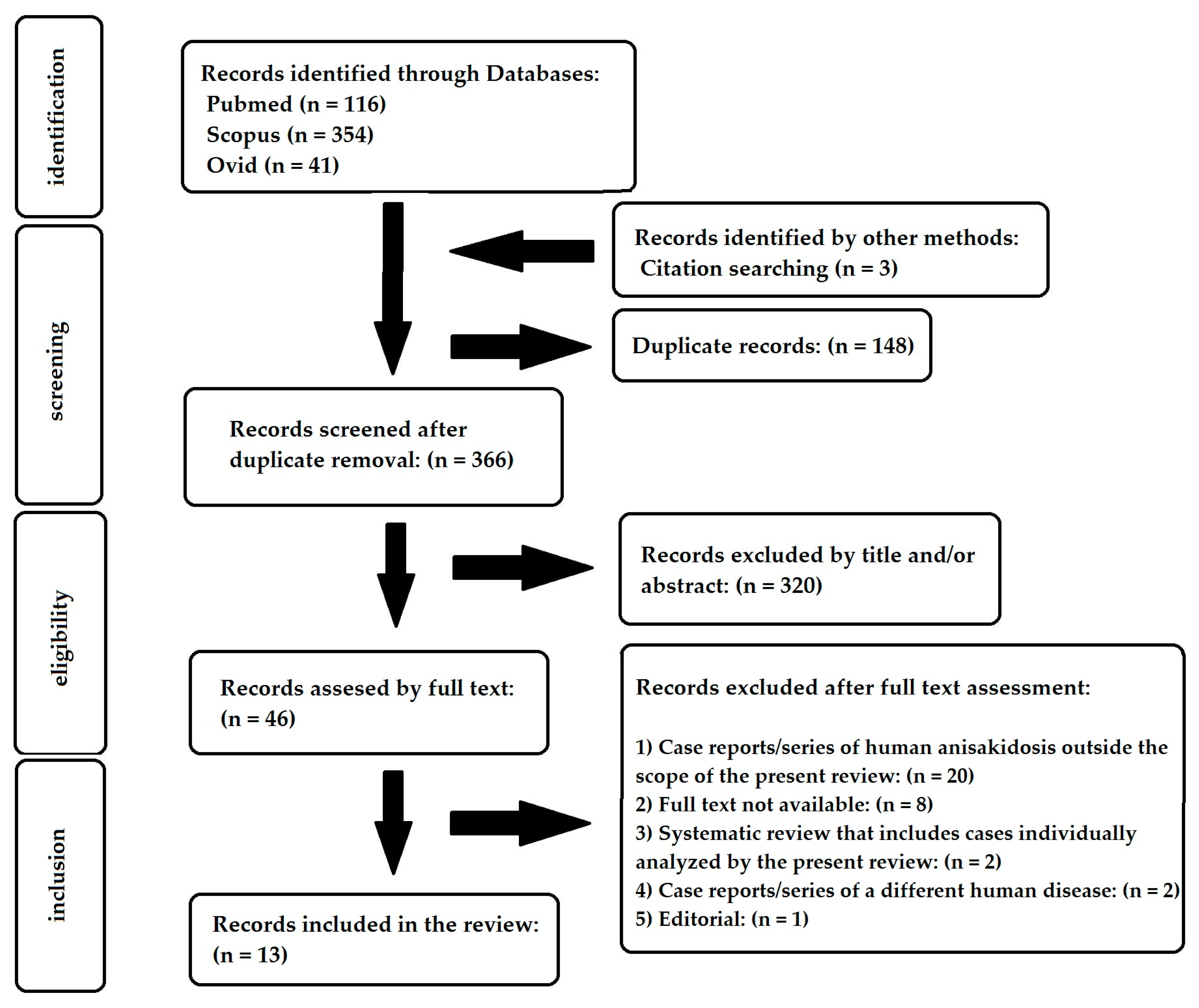

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Eligibility

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Data Extraction

3. Results

3.1. Included Studies and Epidemiological Data

3.2. Anatomical Localization and Clinical Presentation

3.3. Diagnosis

3.4. Parasitological Findings

3.5. Involvement of Other Organs

3.6. Treatment and Prognosis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adroher-Auroux, F.J.; Benítez-Rodríguez, R. Anisakiasis and Anisakis: An underdiagnosed emerging disease and its main etiological agents. Res. Vet. Sci. 2020, 132, 535–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsi, S.; Barton, D.P. A critical review of anisakidosis cases occurring globally. Parasitol. Res. 2023, 122, 1733–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadler, A.S.; Hudspeth, S.S.D. Ribosomal DNA and Phylogeny of the Ascaridoidea (Nemata: Secernentea): Implications for morphological Evolution and Classification. Mol. Phylogenetics Evol. 1998, 10, 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamsi, S. Recent advances in our knowledge of Australian anisakid nematodes. Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 2014, 3, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieuwenhuizen, N.E.; Lopata, A.L. Anisakis—A food-borne parasite that triggers allergic host defences. Int. J. Parasitol. 2013, 43, 1047–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.C. Order Rhabditida. In Nematode Parasites of Vertebrates: Their Development and Transmission, 2nd ed.; CABI Publishing: Wallingford, UK, 2000; pp. 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochberg, N.S.; Hamer, D.H. Anisakidosis: Perils of the deep. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2010, 51, 806–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anisakiasis; U.S Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/anisakiasis/index.html (accessed on 29 March 2025).

- Shamsi, S. Parasite loss or parasite gain? Story of Contracaecum nematodes in antipodean waters. Parasite Epidemiol. Control 2019, 4, e00087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamsi, S.; Briand, J.M.; Justine, J. Occurrence of Anisakis (Nematoda: Anisakidae) larvae in unusual hosts in Southern hemisphere. Parasitol. Int. 2017, 66, 837–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsi, S.; Sheorey, H. Seafood-borne parasitic diseases in Australia: Are they rare or underdiagnosed? Intern. Med. J. 2018, 48, 591–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathison, B.A.; Pritt, B.S. Parasites of the Gastrointestinal Tract. In Encyclopedia of Infection and Immunity; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; Volume 3, pp. 136–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorenza, E.A.; Wendt, C.A.; Dobkowski, K.A.; King, T.L.; Pappaionou, M.; Rabinowitz, P.; Samhouri, J.F.; Wood, C.L. It’s a wormy world: Meta-analysis reveals several decades of change in the global abundance of the parasitic nematodes Anisakis spp. and Pseudoterranova spp. in marine fishes and invertebrates. Glob. Change Biol. 2020, 26, 2854–2866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Pei, X.; Li, Y.; Zhan, L.; Tang, Z.; Chen, W.; Song, X.; Yang, D. Epidemical study of third stage larvae of Anisakis spp. infections in marine fishes in China from 2016 to 2017. Food Control 2020, 107, 106769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eguia, A.; Aguirre, J.M.; Echevarria, M.A.; Martinez-Conde, R.; Pontón, J. Gingivostomatitis after eating fish parasitized by Anisakis simplex: A case report. Oral. Surg. Oral. Med. Oral. Pathol. Oral. Radiol. 2003, 96, 437–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daschner, A. Chapter 31—Risks and Possible Health Effects of Raw Fish Intake. In Fish and Fish Oil in Health and Disease Prevention; Raatz, K.S., Bibus, M.D., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016; pp. 341–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, J.G. The “New Disease” Status of Human Anisakiasis and North American Cases: A Review. J. Milk. Food Technol. 1975, 38, 769–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilauro, S.; Crum-Cianflone, N.F. Ileitis: When it is not Crohn’s disease. Curr. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2010, 12, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, P.; Jercic, M.I.; Weitz, J.C.; Dobrew, E.K.; Mercado, R.A. Human pseudoterranovosis, an emerging infection in Chile. J. Parasitol. 2007, 93, 440–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacomino, E.; Sinatti, G.; Pasqua, M.; Tucci, C.; Picchi, G.; Cipolloni, G.; Marco, G. Anisakis in oral cavity: A rare case of an emerging disease. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. Cases 2020, 6, 100136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardona, V.; Guilarte, M.; Labrador-Horrillo, M. Molecular diagnosis usefulness for idiopathic anaphylaxis. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2020, 20, 248–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawanishi, K.; Ikeda, Y.; Furotani, M.; Tsuboi, S.; Kanno, T.; Niwa, T.; Nagaoka, T.; Tabata, Y.; Kitano, M. Fifty—Illimeter abscess in the ileum caused by perforation from anisakiasis successfully treated with conservative therapy without drainage. Oxf. Med. Case Rep. 2021, 2021, omab033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujikawa, H.; Kuwai, T.; Yamaguchi, T.; Miura, R.; Sumida, Y.; Takasago, T.; Miyasako, Y.; Nishimura, T.; Iio, S.; Imagawa, H.; et al. Gastric and enteric anisakiasis successfully treated with Gastrografin therapy: A case report. World J. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2018, 10, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lymbery, A.J.; Walters, J.A. Helminth-Nematode: Anisakid Nematodes. In Encyclopedia of Food Safety; Motarjemi, Y., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014; pp. 78–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, A.C., Jr.; Lewis, M.D.; Hauser, M.L. Proper identification of anisakine worms. Am. J. Med. Technol. 1983, 49, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Park, J.Y.; Park, Y.J.; Ko, H.S.; Song, Y.J. Anisakiasis in oral cavity: A case report. Korean J. Otolaryngol.-Head. Neck Surgery. 2006, 49, 763–765. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, S.K.; Kim, C.K.; Kim, S.H.; Jo, D.I. Anisakiasis Involving the Oral Mucosa. Arch. Craniofacial Surg. 2017, 18, 261–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.H.; Chung, B.S.; Moon, Y.I.; Chun, S.H. A case report on human infection with Anisakis sp. in Korea. Kisaengchunghak Chapchi. 1971, 9, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhargava, D.; Raman, R.; El Azzouni, M.Z.; Bhargava, K.; Bhusnurmath, B. Anisakiasis of the tonsils. J. Laryngol. Otol. 1996, 110, 387–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takano, K.; Okuni, T.; Murayama, K.; Himi, T. A Case Study of Anisakiasis in the Palatine Tonsils. Adv. Otorhinolaryngol. 2016, 77, 125–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukui, S.; Matsuo, T.; Mori, N. Palatine Tonsillar Infection by Pseudoterranovaazarasi. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2020, 103, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, E.J.; Kim, J.S.; Heo, S.J. Anisakiasis in Palatine Tonsil. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2022, 33, 692–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumagai, M. An unusual body in the soft palate. Nihon Univ. J. Med. 2006, 48, 79–81. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, J.H.; Kim, E.J.; Park, S.H.; Kim, S.W. A Case of Anisakiasis Invading the Oropharynx. Korean J. Otorhinolaryngol.-Head. Neck Surg. 2015, 58, 284–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumagai, K.; Hirose, Y.; Yoshida, S. Woman with Foreign Body on Her Tongue. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2018, 72, 121–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, S.; Bandoh, N.; Goto, T.; Uemura, A.; Sasaki, M.; Harabuchi, Y. Severe laryngeal edema caused by Pseudoterranova species: A case report. Medicine 2021, 100, 24456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassona, Y.; Scully, C.; Delgado-Azanero, W.; de Almeida, O.P. Oral helminthic infestations. J. Investig. Clin. Dent. 2015, 6, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baptista-Fernandes, T.; Rodrigues, M.; Castro, I.; Paixão, P.; Pinto-Marques, P.; Roque, L.; Belo, S.; Ferreira, P.M.; Mansinho, K.; Toscano, C. Human gastric hyperinfection by Anisakis simplex: A severe and unusual presentation and a brief review. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2017, 64, 38–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aibinu, I.E.; Smooker, P.M.; Lopata, A.L. Anisakis Nematodes in Fish and Shellfish—From infection to allergies. Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 2019, 9, 384–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moneo, I.; Carballeda-Sangiao, N.; González-Muñoz, M. New Perspectives on the Diagnosis of Allergy to Anisakis spp. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2017, 17, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzucco, W.; Raia, D.D.; Marotta, C.; Costa, A.; Ferrantelli, V.; Vitale, F.; Casuccio, A. Anisakis sensitization in different population groups and public health impact: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, 0203671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heffler, E.; Sberna, M.E.; Sichili, S.; Intravaia, R.; Nicolosi, G.; Porto, M.; Liuzzo, M.T.; Picardi, G.; Fichera, S.; Crimi, N. High prevalence of Anisakis simplex hypersensitivity and allergy in Sicily, Italy. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2016, 116, 146–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-López, J.; Gázquez, V.; Rubira, N.; Valdesoiro, L.; Guilarte, M.; Garcia-Moral, A.; Depreux, N.; Soto-Retes, L.; De Molina, M.; Luengo, O.; et al. Food allergy in Catalonia: Clinical manifestations and its association with airborne allergens. Allergol. Immunopathol. 2017, 45, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattiucci, S.; Fazii, P.; De Rosa, A.; Paoletti, M.; Megna, A.S.; Glielmo, A.; De Angelis, M.; Costa, A.; Meucci, C.; Calvaruso, V.; et al. Anisakiasis and gastroallergic reactions associated with Anisakis pegreffii infection, Italy. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2013, 19, 496–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigehira, Y.; Inomata, N.; Nakagawara, R.; Okawa, T.; Sawaki, H.; Nakamura, K.; Kobayashi, Y.; Shiomi, K.; Ikezawa, Z. A case of an allergic reaction due to Anisakis simplex after the ingestion of salted fish guts made of Sagittated calamari: Allergen analysis with recombinant and purified Anisakis simplex allergens. Arerugi 2010, 59, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Barbarroja-Escudero, J.; Rodriguez-Rodriguez, M.; Sanchez-Gonzalez, M.J.; Antolin-Amerigo, D.; Alvarez-Mon, M. Anisakis simplex: A new etiological agent of Kounis syndrome. Int. J. Cardiol. 2013, 167, 187–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Ref. | Publication Year | Sex | Age | Country | Anatomical Localization | Consumed Food |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [19] | 2007 | M | 40 | Chile | Oral cavity | Pomfret (raw, ceviche) |

| [26] | 2006 | M | 31 | Korea | Oral mucosa (buccal mucosa and tongue) | Squid (raw) |

| [27] | 2017 | M | 39 | Korea | Oral mucosa (buccal and labial mucosa) | Cuttlefish (raw) |

| [20] | 2019 | F | 59 | Italy | Oral mucosa (buccal mucosa) | Fish (raw) |

| [28] | 1971 | F | 27 | Korea | Palatine tonsil | Squid (raw) |

| [29] | 1996 | F | 6 | Oman | Palatine tonsil | Mackerel, sardines, prawns (likely improperly cooked) |

| [30] | 2016 | M | 68 | Japan | Palatine tonsil | Tuna (raw, sashimi) |

| [31] | 2020 | F | 25 | Japan | Palatine tonsil | (raw, sashimi) |

| [32] | 2022 | F | 54 | Korea | Palatine tonsil | Fish (raw) |

| [33] | 2006 | M | 35 | Japan | Soft Palate | Squid |

| [34] | 2015 | F | 46 | Korea | Soft Palate | Halibut, tuna (raw, sashimi) |

| [35] | 2018 | F | 38 | Japan | Tongue | Squid (raw, sushi) |

| [36] | 2021 | F | 69 | Japan | Tongue | Jacopever (raw, sashimi) |

| Ref. | Time from Food Consumption to Symptom Onset | Time from Symptom Onset to Consultation | Patient’s Main Complaint | Clinical/Endoscopic Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [19] | - | - | Foreign body sensation between the teeth | - |

| [26] | Immediately | - | Oral pain | Moving whitish worms measuring 1 × 10 cm penetrating the oral mucosa. |

| [27] | 30 min | 1 day | Oral and sub-sternal pain | Erythematous and edematous lesions. In the center of each lesion, a white worm was observed penetrating the oral mucosa. |

| [20] | Immediately | 2 months | Neck rash, right cheek pain | An erythematous and edematous lesion in the oral mucosa, under which a nodule with a smooth surface and of fibrous texture was palpated. |

| [28] | - | - | Foreign body sensation and swallowing difficulty | Enlargement of both palatine tonsils. A white worm found in the left tonsillar crypt. |

| [29] | - | - | Symptoms suggestive of chronic recurrent tonsillitis and adenoiditis | - |

| [30] | Immediately | 3 days | Throat pain | Right submandibular edematous swelling. Intraorally, a mucosal swelling involving the right tonsil and the soft palate, with a white worm observed over the tonsil. |

| [31] | Immediately | 5 days | Throat pain and irritation | A moving black worm in the left tonsil. |

| [32] | Immediately | 10 days | Throat pain and irritation, foreign body sensation | A moving white worm, which was seen penetrating the mucosa of the right tonsillar crypt. |

| [33] | Immediately | 2 h | Throat pain | - |

| [34] | 30 min | - | Pain around the uvula | A moving brown worm measuring 3 × 0.5 cm, which was seen penetrating the mucosa of the left pharyngopalatine arch. |

| [35] | Immediately | 10 h | Sticking sensation, observation of a foreign body on the tongue | A white worm, surrounded by an area of erythema and swelling, on the left half of the dorsum of the tongue. |

| [36] | 4 days | 8 h | Throat blockage feeling and irritation | Edema of the left arytenoid and the epiglottis. A moving white-yellowish worm observed on the base of the tongue. |

| Ref. | CBC with Leucocyte Differentiation | Inflammatory Markers | Antibody Serology |

|---|---|---|---|

| [27] | Normal | Normal CRP | - |

| [30] | Eosinophilia with normal leucocyte count | Minor CRP elevation | Elevated Total Serum IgE, Anisakis-specific IgE highly positive, Anisakis-specific IgG positive, Anisakis-specific IgA positive |

| [32] | - | - | Normal Total Serum IgE, Anisakis-specific IgE negative |

| [34] | Normal | Normal ESR | - |

| [36] | Normal | Minor CRP elevation | Elevated Total Serum IgE, Anisakis-specific IgE highly positive, IgE specific for fish and squid negative |

| Ref. | Number of Larvae | Larvae Species | Larvae State of Preservation | Method of Parasite Identification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [19] | 1 | Pseudoterranova sp. | - | Microscopic |

| [26] | 20 | Anisakis simplex | Alive | - |

| [27] | 8 | Anisakis simplex | Alive | - |

| [20] | 1 | Anisakis sp. | - | Microscopic |

| [28] | 1 | Anisakis sp. | Alive | Microscopic |

| [29] | 1 | Anisakis sp. | Dead (degenerating) | Microscopic |

| [30] | 1 | Anisakis sp. | Alive | Microscopic |

| [31] | 1 | Pseudoterranova azarasi | Alive | Molecular (PCR) |

| [32] | 1 | Anisakis sp. | Alive | Microscopic |

| [33] | - | Anisakis sp. | - | - |

| [34] | 1 | Anisakis sp. | Alive | Microscopic |

| [35] | 1 | Anisakis sp. | - | - |

| [36] | 1 | Pseudoterranova sp. | Alive | Microscopic |

| Ref. | Treatment | Recovery and Follow-Up |

|---|---|---|

| [19] | Larvae removal | - |

| [26] | Surgery (mucosal resection) | Patient discharged free of symptoms 1 day after larvae removal, free of disease (1 month follow-up) |

| [27] | Larvae removal | Patient discharged free of symptoms 1 day after larvae removal |

| [20] | Surgery (nodule excision) | Patient discharged free of symptoms post-operation |

| [28] | Larvae removal | Immediate symptom improvement after larvae removal |

| [29] | Surgery (tonsillectomy) | Free of disease (2-month follow-up) |

| [30] | Larvae removal | Immediate symptom improvement after larvae removal, patient discharged free of symptoms 10 days afterwards |

| [31] | Larvae removal | Immediate symptom improvement after larvae removal |

| [32] | Larvae removal | Immediate symptom improvement after larvae removal, free of disease (12-month follow-up) |

| [33] | Larvae removal | Immediate symptom improvement after larvae removal |

| [34] | Larvae removal | Immediate symptom improvement after larvae removal, free of disease (1-month follow-up) |

| [35] | Larvae removal | - |

| [36] | Larvae removal, intravenous antibiotics, and corticosteroids | Symptom improvement 1 day after larvae removal, patient discharged free of symptoms 3 days afterwards |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Papadopoulos, S.; Zisis, V.; Poulopoulos, K.; Charisi, C.; Poulopoulos, A. Human Anisakidosis with Intraoral Localization: A Narrative Review. Parasitologia 2025, 5, 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/parasitologia5030041

Papadopoulos S, Zisis V, Poulopoulos K, Charisi C, Poulopoulos A. Human Anisakidosis with Intraoral Localization: A Narrative Review. Parasitologia. 2025; 5(3):41. https://doi.org/10.3390/parasitologia5030041

Chicago/Turabian StylePapadopoulos, Stylianos, Vasileios Zisis, Konstantinos Poulopoulos, Christina Charisi, and Athanasios Poulopoulos. 2025. "Human Anisakidosis with Intraoral Localization: A Narrative Review" Parasitologia 5, no. 3: 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/parasitologia5030041

APA StylePapadopoulos, S., Zisis, V., Poulopoulos, K., Charisi, C., & Poulopoulos, A. (2025). Human Anisakidosis with Intraoral Localization: A Narrative Review. Parasitologia, 5(3), 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/parasitologia5030041