Society and Mining: Reimagining Legitimacy in Times of Crisis—The Case of Panama

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Diagnose the institutional, political, and social factors that produced Panama’s 2023 mining legitimacy crisis;

- Interpret how diverse stakeholders perceive fairness, accountability, and institutional credibility;

- Identify governance mechanisms and minimum conditions that could rebuild trust across extractive development in polarized scenarios;

- Propose the Social Legitimacy for Mining (SLM) framework as a multi-actor, governance-oriented model for restoring trust in post-crisis contexts.

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

2.1. Rethinking Legitimacy in Mining

2.2. Governance, Good Governance, and Its Role in Legitimacy

2.3. Translating Good Governance into Mining Mechanisms

- The Social License to Operate (SLO) is an informal, dynamic form of community approval grounded in trust and engagement rather than legal compliance [34]. It has influenced ESG standards and corporate practice globally, but risks devolving into a narrow reputation management tool that overlooks structural power asymmetries and the role of state institutions [41,42].

- Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC), rooted in ILO Convention 169 and UNDRIP [43], codifies Indigenous peoples’ right to consent to projects affecting their territories. While fundamental to Indigenous rights, FPIC has limitations in pluralistic contexts where it risks becoming a procedural box-checking exercise, insufficient to address inequities or incorporate non-Indigenous stakeholders [20,44].

2.4. Beyond Procedural Frameworks

2.5. Advancing Social Legitimacy for Mining

Mapping SLM to Theories

- Pillar I—Credibility

- Procedural justice → Input/throughput legitimacy; Suchman’s pragmatic–moral–cognitive lenses [18].Focus: fair, transparent, reasons-giving procedures; predictable timelines; accessible remedy.Contribution: translates “fair process” into auditable practices (publication of technical reports, written reasons, grievance service levels).

- Institutional trust → Institutional theory: Meyer & Rowan (decoupling); DiMaggio & Powell (isomorphism) [54,55].Focus: alignment between formal rules and enforcement across electoral cycles.Contribution: explains why compliance without credibility fails; specifies continuity mechanisms (statutory oversight, budgeted mandates, independent review).

- Pillar II—Inclusion

- Epistemic legitimacy → Extension of cognitive legitimacy; epistemic justice/knowledge pluralism.Focus: recognition and co-production of scientific, Indigenous, and local knowledge in baselines, assessment, and monitoring.Contribution: makes “whose knowledge counts” measurable (co-produced baselines, joint monitoring, open data).

- Relational governance → Stakeholder & stakeholder-salience (power/legitimacy/urgency); polycentric governance; political ecology.Focus: how state, industry, Indigenous authorities, communities, NGOs, faith-based actors, and media co-produce acceptance across scales; how histories, material ecologies, and justice claims shape contestation.Contribution: embeds multi-actor oversight and participation ladders as durable interfaces; surfaces distributional/territorial justice dynamics (political ecology).

2.6. Research Gap and Justification

3. Methods

3.1. Research Design and Philosophical Orientation

3.2. Case Selection, Boundaries, and Units of Analysis

Units of Analysis

- Local communities—directly affected populations whose perspectives illuminate procedural justice and relational governance.

- Institutional actors—regulatory, judicial, and policy bodies central to institutional trust and credibility.

- National stakeholders—a diverse group including Indigenous leaders, business chambers, activists, academics, students, and legal/policy experts. These actors influence public discourse, generate competing knowledge claims, and shape epistemic legitimacy and broader societal acceptance.

3.3. Data Collection

3.4. Data Analysis

- Deductive coding used sensitizing concepts from the proposed SLM framework—procedural justice, institutional trust, epistemic legitimacy, relational governance—and institutional constructs (decoupling; coercive/mimetic/normative pressures).

- Inductive coding captured emergent themes, including social-movement dynamics, perceived corruption, misinformation, environmental concerns, and distributional fairness.

3.5. Reflexivity and Limitations

4. Results

4.1. Procedural Justice: Transparency, Accountability, and Institutional Weakness

4.2. Trust and Institutional Credibility

4.3. Epistemic Legitimacy: Divergent Knowledge Claims and Environmental Concerns

4.4. Relational Governance: Intermediaries, Inclusion, and Plural Voices

4.5. Cross-Cutting Insight

5. Discussion

5.1. Legitimacy Beyond Technical Compliance

5.2. Trust, Institutions, and the Reconstruction of Legitimacy

5.3. Plural Voices and Uneven Influence

5.4. Global Frameworks, Local Skepticism

5.5. Toward a Stakeholder-Informed Framework: Social Legitimacy for Mining (SLM)

- Frames legitimacy as ongoing and interactive, shaped through four dimensions: procedural justice, institutional trust, epistemic legitimacy, and relational governance.

- Emphasizes multi-scalar applicability, from local to national and global levels.

- Incorporates stakeholder salience to analyze how power, legitimacy, and urgency shift across crises [58].

- Provides practical diagnostic tools to identify legitimacy breakdowns and chart pathways for restoration.

5.6. Scope and Transferability

- Transferable elements of SLM include:

- Procedural practices (reasons-giving, open data, participatory decision making)

- Institutional designs (credible and election-resilient oversight mechanisms)

- Epistemic strategies (co-produced baselines and transparent monitoring)

- SLM applied to Panama—context-specific aspects include:

- The dynamics of five-year electoral cycles and policy discontinuity

- The strong role of faith-based organizations and Indigenous authorities as trust intermediaries

6. Policy and Practice Implications

- Institutionalize Binding Commitments: full implementation of Panama’s Escazú Agreement (The Escazú Agreement (2018) is a legally binding regional treaty for Latin America and the Caribbean that guarantees rights of access to environmental information, participation, and justice, and includes provisions to protect environmental defenders) obligations—ensuring timely information access, participatory decision-making, and effective grievance mechanisms—could address core transparency and accountability concerns identified by participants. {Procedural justice; Institutional trust—aligns with Section 4.1 and Section 4.2.}

- Integrate Measurable Standards in Regulation: while interviewees expressed skepticism toward voluntary initiatives, frameworks such as Towards Sustainable Mining (TSM) (Towards Sustainable Mining (TSM) is a performance-based sustainability program created by the Mining Association of Canada in 2004 [87]; it requires participating companies to measure and publicly report on environmental and social performance across areas such as tailings management, community engagement, and biodiversity, with external verification to ensure transparency) formally endorsed by the Panamanian Chamber of Mines, CAMIPA, and ICMM Performance Expectations [88] provide reference points for responsible practice. Their integration into public regulation, alongside independent oversight, may enhance institutional credibility. {Institutional trust; Relational governance—Section 4.2 and Section 4.4.}

- Structure participation using IAP2-inspired gradations: to demonstrate progression from informing to collaboration and shared decisions, SLM incorporates participatory gradations inspired by the IAP2 Spectrum [48]. {Procedural justice; Relational governance; Epistemic legitimacy—Section 4.1, Section 4.3 and Section 4.4; Appendix G.}

- Build Capacity and Empower Stakeholders: long-term legitimacy is likely to require sustained investment in technical, legal, and monitoring skills for regulators, communities, Indigenous organizations, and civil society, to ensure meaningful participation and oversight. {Epistemic legitimacy; Relational governance—Section 4.3 and Section 4.4.}

- Foster Multi-Actor Oversight Structures: aligning with SLM’s emphasis on relational governance, multi-actor oversight entities can support joint monitoring, deliberation, and accountability, but should be shaped by ongoing stakeholder input to reflect diverse perspectives and needs. {Relational governance; Institutional trust—Section 4.2 and Section 4.4.}

- Create a Depoliticized Mining Authority: to address institutional fragility and restore credibility, stakeholders emphasized the need for an autonomous, professionalized body capable of regulating the mining sector at arm’s length from partisan politics. In collaboration with the previous government (2019—2024), the IDB proposed the establishment of such a depoliticized Mining Authority in Panama to ensure consistency, technical rigor, and accountability in governance. Anchoring this authority in law—with transparent appointment processes, independent funding mechanisms, and structured stakeholder representation—could mitigate risks of political capture, strengthen institutional trust, and provide a stable foundation for long-term sector governance [44]. {Institutional trust; Procedural justice—Section 4.2, Section 4.1.}

7. Conclusions

7.1. The Future of Mining and the Mining of the Future

7.2. Contribution and Way Forward

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CAMIPA | Cámara Minera de Panamá (Panamanian Chamber of Mining) |

| CoNEP | Consejo Nacional de la Empresa Privada (National Council of Private Enterprise, Panama) |

| ESG | Environmental, Social, and Governance |

| FPIC | Free, Prior and Informed Consent |

| GRI | Global Reporting Initiative |

| IAP2 | International Association for Public Participation |

| ICMM | International Council on Mining and Metals |

| IDB | Inter-American Development Bank |

| IFC | International Finance Corporation |

| IGF | Intergovernmental Forum on Mining, Minerals, Metals and Sustainable Development |

| ILO | International Labour Organization |

| IRMA | Initiative for Responsible Mining Assurance |

| MAC | Mining Association of Canada |

| MP3 | MPEG Audio Layer-3 (digital audio format) |

| NGO(s) | Non-Governmental Organization(s) |

| NVivo | Qualitative Data Analysis Software (QSR International) |

| Portable Document Format | |

| SDG(s) | Sustainable Development Goal(s) |

| SLO | Social License to Operate |

| SLM | Social Legitimacy for Mining |

| TSM | Towards Sustainable Mining |

| UNDP | United Nations Development Programme |

| UNDRIP | United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples |

| UNSDG(s) | United Nations Sustainable Development Goal(s) |

Appendix A. Cross-Case Comparative Matrix—Themes Summary

| Stakeholder Type | Reasons for Ban (2023) | Governance & Trust Issues | Conditions for Acceptance | Vision of Development |

| Government/Political | Public discontent with corruption, rushed contract approval, political exhaustion | Weak institutions, lack of long-term planning, corruption | Clear rules, transparency, stronger oversight, depoliticized mining authority | Mining as part of national plan if well-governed |

| Lawyers/Legal Experts | Legal uncertainty, poor communication, weak oversight, contract rushed | Improvisation, unstable regulations, lack of legal clarity | Robust legal framework, standardized contracts, stronger institutions, transparency | Mining compared to Panama Canal—potential pride if benefits are shared |

| Civil Society/Communities | Government mistrust, unfair distribution, corruption, environmental fears, social media activism | Distrust of government, misinformation, politicization, weak communication | Fair distribution, transparency, stronger institutions, engagement, safeguards | Mining accepted only if benefits are tangible and fair |

| Technical Experts | Public ignorance, misinformation, weak/obsolete laws, opportunism, short-term politics | Corruption, weak oversight, lack of continuity, outdated constitution | Mining ‘done right’, education, governance reforms, long-term planning | Cultural/educational reform needed; responsible mining possible with rehabilitation |

| Activists | Distrust of government, betrayal of sovereignty, inequality, ecological concerns | State lacks credibility, weak institutions, poor transparency | Practically impossible under current governance; hypothetical net-positive mining | Alternatives to mining: biodiversity, logistics, services; leave minerals underground |

Appendix B. Interview Guide

- Sample of Semi-Structured Interview Guide

- Can you describe your current role or experience as it relates to the mining sector in Panama?

- How have you or your organization been involved—directly or indirectly—with mining issues, decisions, or policies in the country?

- 3.

- What is your perspective on Panama’s 2023 national ban on metallic mining?

- 4.

- In your view, what were the main drivers or turning points that led to the prohibitions in place for mining? Are there specific events or concerns you consider decisive?

- 5.

- Do you believe this decision reflected a breakdown in public trust or legitimacy? Why or why not?

- 6.

- What does “legitimate” mining governance mean to you? Can you offer an example?

- 7.

- In your opinion, what makes a mining project responsible or acceptable?

- 8.

- Do you think trust in mining governance can be restored in Panama? If so, what would it take? How would you know if legitimacy had been restored?

- 9.

- What forms of engagement or consultation do you consider meaningful? What would make engagement feel genuine rather than tokenistic?

- 10.

- Which actors or groups should be involved in decisions about mining, and why?

- 11.

- How should Indigenous Peoples and local communities be included in mining decisions to ensure their perspectives are meaningfully considered?

- 12.

- Have you observed any power imbalances or conflicts between stakeholder groups? How do these affect trust and legitimacy?

- 13.

- Do you think gender or other aspects of identity affect whose voices are heard in mining governance?

- 14.

- Do you think current governance structures are capable of rebuilding trust and legitimacy? Why or why not?

- 15.

- If mining were to resume in Panama, what specific governance reforms or institutional changes would you consider essential for restoring trust and legitimacy?

- 16.

- What changes would you like to see in how government or companies engage with society?

- 17.

- What role do transparency and accountability play in regaining public trust?

- 18.

- Whose knowledge or perspectives do you think are most valued in mining decisions? Are there voices or knowledge systems that are often overlooked?

- 19.

- Do you think Panama needs a new way of thinking about how trust and legitimacy in mining are built and maintained? Why or why not?

- 20.

- Would you support an approach that brings in the voices of different sectors of society—not just communities near mining sites? What principles or values should guide such a framework?

- 21.

- Is there anything else you would like to add about mining, governance, or community engagement in Panama?

- 22.

- Are there any reports, individuals, or cases you recommend I review as part of this study?

- 23.

- Would you like to receive a summary of the study’s findings (See Appendix H: Plain-language Summary Example for Post-interview Feedback Process)? If so, what is your preferred method of contact (email, WhatsApp, etc.)?

Appendix C. Typology of Stakeholders and Purpose

| Category | Stakeholder Examples | Purpose |

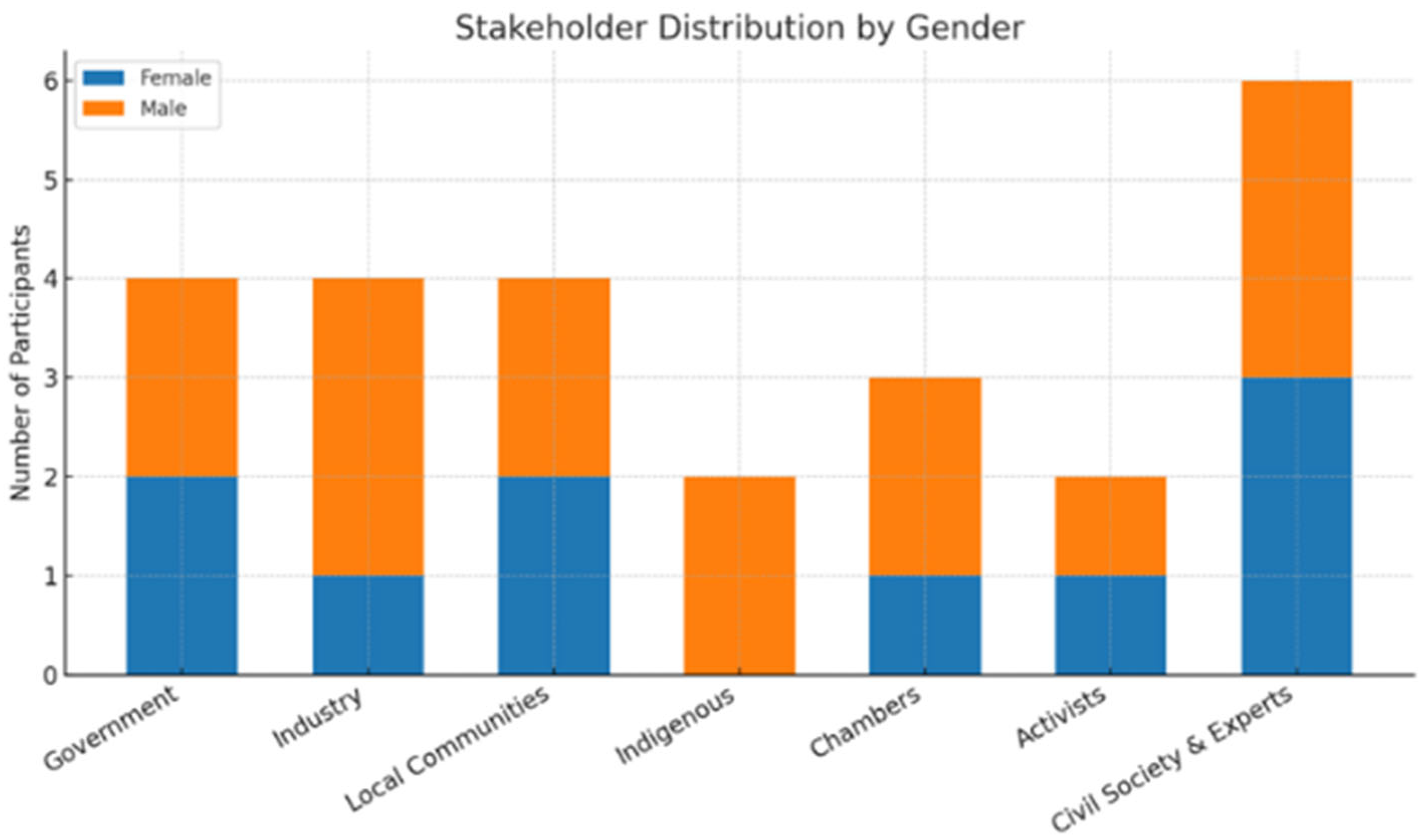

| Diversity of Perspectives | Gender, age, cultural background, socio-economic position. | Capture varied experiences that shape views on legitimacy and governance. Efforts to include underrepresented voices. |

| Local Communities | Residents, suppliers and leaders in mining areas. | Capture lived experiences, concerns, and expectations of benefits or safeguards. |

| Indigenous Groups | Authorities representing Indigenous territories. | Explore rights claims, worldviews, and experiences with extractive industries. |

| Civil Society/NGOs | Environmental groups, activists, faith-based groups, labor unions. | Reflect wider debates on environment, social justice, and democratic accountability. |

| Industry | Mining executives, business chambers, sector associations. | Understand corporate priorities, economic interests, and governance expectations. |

| Academics/Legal Experts | Lawyers, scholars, and policy specialists. | Provide analysis of legal frameworks, constitutional issues, and legitimacy debates. |

| Government Actors | Past and present representatives (mining authorities, regulatory officials, legislators) | Capture perspectives on policy design, enforcement capacity, and institutional trust. |

Appendix D. List of Additional Notable Quotes from Interviewees in No Specific Order

| Quotes |

| “The government simply does not have the capacity or credibility to monitor a project of this size. People assumed corruption, and trust collapsed.” |

| “When no clear data is available, people imagine the worst. Fear spreads faster than facts.” |

| “Mining could transform Panama’s economy if managed transparently. It brings revenues and jobs that no other sector can match.” |

| “The country cannot depend only on the Canal. Mining offers a chance to diversify and fund social programs.” |

| “With so much rain, tailings are simply too risky here. The climate itself makes mining unviable here.” |

| “Even if mining could help the economy, no one trusts the institutions to manage it fairly.” |

| “Without transparency, no reform will matter. People must see the numbers and the monitoring in real time.” |

| “Unless rules outlast the five-year political cycle, nothing will change. Stability is part of legitimacy.” |

| “There are examples of responsible mining in Latin America. Panama could learn from them instead of banning the sector outright.” |

| “Without trusted information, people imagine the worst. If local governments were stronger, communities educated, and companies truly part of the community, mining could be seen differently.” |

| “If the community sees transparency, stronger institutions, and real benefits, mining could be accepted—but not under the old model of secrecy and corruption.” |

| “Communities paid the price in health and environment but saw no benefits—mining will only be accepted if people are included and truly see the results.” |

| “People saw wealth leaving the mine but not reaching their communities—if mining returns, it must bring real benefits and be managed with honesty.” |

| “Mining needs independent oversight and credible institutions to be seen as legitimate. Trust must be rebuilt step by step—and young voices must be part of shaping that change.” |

| “People rejected mining not just for the contract, but because they don’t trust the government. Transparency is the key.” |

| “Without legal certainty and strong institutions, mining in Panama will always face rejection—contracts must be clear, transparent, and genuinely beneficial to the people.” |

| “For mining to be accepted, people must identify with it as they do with the Canal. That sense of ownership, supported by education and trust-building, could take a generation to achieve.” |

| “The contract fell because of distrust. Mining can only return if oversight improves and citizens see tangible benefits.” |

| “Mining can regain acceptance if we improve communication, ensure transparency, and demonstrate clear benefits for society.” |

| “Just as the Canal gave Panamanians a sense of ownership, mining too must be seen as ours. But legitimacy will take a generation to be regained, it needs to be shaped by today values of equality, minority rights, and environmental protection.” |

| “If you can see the scar of Donoso from space on Google Maps, of course people are afraid—but with more education and transparency, in 5 or 10 years I believe mining could be accepted again.” |

| “The problem is not mining itself but doing it the wrong way—with weak laws, poor oversight, and without educating the population.” |

| “Is it really worth sacrificing our ecosystems and the future of our children just to send copper abroad, while the people see no real benefit?” |

| “Even if mining could help the economy, no one trusts the institutions to manage it fairly.” |

| “Mining is a necessity in today’s world, but in Panama it should only proceed if the operations minimize negative impacts and protect biodiversity.” |

| “We cannot let short-term economic pressure undo the protection of our environment and our communities.” |

Appendix E. Codebook Sample

| Parent | Node | Description | SearchQuery |

| SLM Conditions | Procedural legitimacy | Perceptions of fairness, due process, and procedural justice in decisions about mining. | “procedural justice” OR fairness OR “due process” OR legitimacy OR legitimate |

| SLM Conditions | Institutional trust (distrust) | Trust in state institutions and oversight; mentions of distrust, mistrust, corruption, opacity. | distrust OR mistrust OR “lack of trust” OR corruption OR opacity OR “institutional trust” |

| SLM Conditions | Transparency & communication | Calls for open information, credible spokespeople, and ongoing communication about impacts and benefits. | transparency OR transparent OR communicat * OR communication OR disclosure OR “open data” |

| SLM Conditions | Participation & inclusion | Beyond consultation; inclusion of communities, youth, and Indigenous groups in decision-making. | participation OR inclusive OR inclusion OR consult * OR “co-decision” OR “co-governance” OR empower * |

| SLM Conditions | Capacity building | Education, technical training, and institutional strengthening to enable equitable engagement. | “capacity building” OR training OR education OR literacy OR upskilling OR “technical capacity” |

| SLM Conditions | Benefit distribution | Equitable and visible sharing of royalties and benefits at national and local levels. | benefit * OR royalty OR royalties OR “benefit sharing” OR distribution OR equitable OR fairness |

| SLM Conditions | Long-term strategy (vs short-termism) | Critiques of 5-year cycles; calls for long-term planning, stability, and policy continuity. | “long-term” OR long term OR strategy OR strategic OR continuity OR “short-term” OR short term OR volatility |

| SLM Conditions | Digital misinformation | Role of social media, fake news, and disinformation ecosystems in shaping perceptions. | “social media” OR misinformation OR disinformation OR “fake news” OR networks OR platforms |

| SLM Conditions | Environmental stewardship | Environmental risks, safeguards, monitoring, rehabilitation, and biodiversity concerns. | Environment * OR pollution OR contamination OR biodiversity OR safeguard * OR rehabilitation * OR mitigation |

| SLM Conditions | Ownership & identification | Sense of national or local ownership (e.g., Canal analogy), pride, belonging, and identification. | ownership OR “sense of ownership” OR belonging OR pride OR identity OR identification OR “Canal” |

| Contextual Dynamics | Divergent development visions | Pro-reform, pragmatic, and post-extractivist/alternative development perspectives. | Vision * OR model * OR extractivism * OR post-extractive * OR alternative development OR diversify * |

| Contextual Dynamics | National vs. local legitimacy | Tensions between national narratives/benefits and local fears/impacts. | national OR local OR community OR territory OR territorial OR municipality OR district |

| Governance Tools | Independent authority & oversight | Proposals for a depoliticized mining authority; credible oversight and enforcement. | authority OR regulator OR oversight OR enforcement OR independent OR autonomous |

| Governance Tools | FPIC & Indigenous rights | Free, Prior and Informed Consent; Indigenous participation, safeguards, and rights. | FPIC OR “free prior” OR indigenous OR comarcas OR rights OR consent |

| The asterisk (*) functions as a wildcard, capturing all word variants sharing the same root (e.g., communicat* = communicate, communication, communicating). | |||

Appendix F. Illustration of SLM Implementation

Appendix G. Adaptation of the IAP2 Spectrum to SLM (Illustrative)

| IAP2 Level | Community Promise | SLM Engagement Goal | Example Practices (Panama) | Verification & Evidence | Responsible Actor(s) | Indicator (Example) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inform | We will keep you informed. | Establish a transparency baseline (necessary but insufficient). | Open-data portal for contracts, EIAs, monitoring; Escazú-consistent publication; site visits. | Third-party audit of portal completeness; document timeliness check. | Regulator; Info authority | % of required docs public; median days to publish |

| Consult | We will listen and acknowledge your concerns and provide feedback on how public input influenced the decision. | Obtain input and show visible feedback loops. | Public hearings; written response-to-comments; multilingual summaries. | File review of decision memos; sample of comment-response logs. | Regulator; proponent | % decisions with reasons; response-time SLA met (%) |

| Involve | We will work with you to ensure that your concerns and aspirations are reflected in the alternatives developed. | Strengthen epistemic legitimacy via co-produced knowledge. | Community/Indigenous technical workshops; participatory mapping; co-produced baselines. | Methods audit; attendance/participation diversity index. | Regulator; communities; Indigenous orgs | % baseline variables co-produced; participation diversity score |

| Collaborate | We will partner with you in each aspect of the decision, including the development of alternatives. | Advance relational governance via joint ownership of strategies and monitoring. | Joint advisory boards; tripartite commissions; participatory monitoring aligned to TSM. | QA/QC of monitoring data; chain-of-custody checks; meeting minutes. | Multi-actor oversight body | % joint stations operational; data QA pass rate |

| Empower † | We will look to you for advice and innovation and incorporate your advice into the decisions as much as possible. | Where legally feasible, institutionalize shared authority in defined domains. | Co-approval in high-risk areas; formal Indigenous roles in territorial governance; community-led monitoring with official standing. | Legal review of mandate; budget execution audit; compliance tracking. | Legislature; regulator; Indigenous bodies | Legal mandate enacted (Y/N); budget execution ≥ X% |

Appendix H. Plain-Language Summary Example for Post-Interview Feedback Process

- Society and Mining: Reimagining Legitimacy in Times of Crisis—The Case of Panama

- Acknowledgment & Purpose

- Summary

- Key Findings from 25 Interviews

- Transparency and trust are central:96% linked the mining crisis to weak institutions, opaque decisions, and a lack of reliable information. People felt left in the dark, fueling rumors and mistrust.

- Deep institutional distrust:Doubts on the state’s ability to manage mining responsibly were constantly raised. Even supporters acknowledged past broken promises and weak oversight.

- Mixed views on mining:

- ○

- 72% saw possible opportunities (jobs, socio-economic development).

- ○

- 80% recognized possible risks, especially environmental.

- Alternative voices matter:

- ○

- 56% cited media and the Catholic Church as more credible than the government.

- ○

- 72% stressed the need to meaningfully include plural voices and knowledge systems.

- Global tools are insufficient:While frameworks such as the Social License to Operate (SLO) (The Social License to Operate (SLO) is the informal, ongoing acceptance of a project by affected communities and stakeholders.) or Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) (Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) is the right of Indigenous peoples to approve or reject projects affecting their lands based on adequate information) were considered useful, stakeholders consider them limited in addressing Panama’s systemic, national-level crisis.

- Recommendations from Stakeholders

- 1.

- Guarantee transparency & accountabilityImplement the Escazú Agreement (The Escazú Agreement is a 2018 regional treaty in Latin America and the Caribbean guaranteeing access to information, public participation, and justice in environmental matters) fully (open contracts, data, revenues).

- 2.

- Adopt binding, measurable standardsMove beyond voluntary promises; integrate tools like Towards Sustainable Mining (TSM)—already endorsed by CAMIPA (Camara Minera de Panama)—into law with independent oversight.

- 3.

- Strengthen public participationFollow International Association for Public Participation (IAP2) (The International Association for Public Participation (IAP2) is a professional body that developed the widely used Public Participation Spectrum to guide stakeholder engagement.) model: information → consultation → collaboration → shared decision-making.

- 4.

- Build institutional & community capacityTrain regulators, Indigenous groups, and civil society to monitor mining effectively.

- 5.

- Create multi-actor oversightJoint bodies of government, industry, and civil society to track performance.

- 6.

- Depoliticize mining governanceEstablish an autonomous, professional mining authority—similar in governance independence to the Panama Canal Authority—to enhance oversight and continuity.

- Next Steps & Invitation for Feedback

References

- Bäckstrand, K. Multi-stakeholder partnerships for sustainable development: Rethinking legitimacy, accountability and effectiveness. Eur. Environ. 2006, 16, 290–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, T.R. Why People Obey the Law, 2nd ed.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bebbington, A.; Fash, B.; Rogan, J. Socio-environmental Conflict, Political Settlements, and Mining Governance: A Cross-Border Comparison, El Salvador and Honduras. Lat. Am. Perspect. 2018, 46, 84–106, (Original work published 2019). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saenz, C. Building legitimacy and trust between a mining company and a community to earn social license to operate: A Peruvian case study. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 453–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spalding, R.J. Breaking Ground: From Extraction Booms to Mining Bans in Latin America; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Arsel, M.; Hogenboom, B.; Pellegrini, L. The extractive imperative and the boom in environmental conflicts at the end of the progressive cycle in Latin America. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2016, 3, 877–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consorcio Gobernanza Minera Panamá, John, T. Boyd Company, & International Trade Advisory Services. Reforma Institucional y Estratégica de la Gobernanza del Sector Minero de Panamá: Socialización de Avances y Resultados del Proyecto (Anexo 5 Fase 3), RG-T3553 Technical Proposal; Inter-American Development Bank (BID): Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- International Monetary Fund (IMF). Panama: Impacto Económico de la Minería. 2024. Available online: https://www.imf.org/es/News/Articles/2024/03/03/cs030324-panama-staff-concluding-statement-of-the-2024-article-iv-mission (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Supreme Court of Panama. Judgment on the Constitutional Challenge to Law 406/2023; Corte Suprema de Justicia de Panamá: Panama City, Panama, 2023. Available online: https://www.gacetaoficial.gob.pa/pdfTemp/29969_A/102832.pdf (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- República de Panamá. Ley 407 de 3 de Noviembre de 2023: Que Prohíbe la Minería Metálica en la República de Panamá. Gaceta Oficial No. 29,904. 2023. Available online: https://www.gacetaoficial.gob.pa/pdfTemp/29904/GacetaNo_29904_20231103.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Bloomberg. Panama’s debt downgraded by S&P to lowest investment grade. Bloomberg, 26 November 2024. Available online: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-11-26/panama-s-debt-downgraded-by-s-p-to-lowest-investment-grade (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Kemp, D.; Owen, J.R. Grievance handling at a foreign-owned mine in Southeast Asia. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2017, 4, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luning, S. Underground: The anthropology of resource extraction. In The Anthropology of Resource Extraction; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2022; pp. 185–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beetham, D. Towards a social-scientific concept of legitimacy. In The Legitimation of Power; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 1991; pp. 3–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaasa, A.; Andriani, L. Determinants of institutional trust: The role of cultural context. Health Econ. Policy Law 2021, 16, 86–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levi, M.; Sacks, A.; Tyler, T. Conceptualizing legitimacy, measuring legitimating beliefs. Am. Behav. Sci. 2009, 53, 354–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CoNEP. Repercusiones Socioeconómicas del Cierre de Operaciones de Cobre Panamá; Consejo Nacional de la Empresa Privada: Panama City, Panama, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Suchman, M.C. Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 571–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, A. Territories of Difference: Place, Movements, Life, Redes; Duke University Press: Durham, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kung, A.; Holcombe, S.; Hamago, J.; Kemp, D. Indigenous co-ownership of mining projects: A preliminary framework for the critical examination of equity participation. J. Energy Nat. Resour. Law 2022, 40, 413–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffat, K.; Zhang, A. The paths to social licence to operate: An integrative model explaining community acceptance of mining. Resour. Policy 2014, 39, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, D.; Owen, J.R. Community relations and mining: Core to business but not “core business”. Resour. Policy 2013, 38, 523–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poelzer, G.; Yu, S. All trust is local: Sustainable development, trust in government and legitimacy in northern mining projects. Resour. Policy 2021, 70, 101888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierre, J.; Peters, B.G. Governance, Politics and the State; Red Globe Press: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, T.G. Governance, good governance and global governance: Conceptual and actual challenges. Third World Q. 2012, 33, 797–814. [Google Scholar]

- Bebbington, A.; Abdulai, A.-G.; Bebbington, D.H.; Hinfelaar, M.; Sanborn, C.A. Governing Extractive Industries: Politics, Histories, Ideas; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franks, D.M.; Davis, R.; Bebbington, A.J.; Ali, S.H.; Kemp, D.; Scurrah, M. Conflict translates environmental and social risk into business costs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 7576–7581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otoo, S.; Agapitova, N.; Behrens, J. The Capacity Development Results Framework; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín, A.; Cunial, S. Mining legitimacy: Governing the politics of resource-based green industrial policy. Inst. Dev. Stud. 2025, 2025, 623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights: Implementing the United Nations “Protect, Respect and Remedy” Framework (HR/PUB/11/04); United Nations: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- International Finance Corporation (IFC). Performance Standards on Environmental and Social Sustainability; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; Available online: https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/topics_ext_content/ifc_external_corporate_site/sustainability-at-ifc/policies-standards/performance-standards (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- Global Reporting Initiative (GRI). GRI 14: Mining Sector Standard; Global Reporting Initiative: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; Available online: https://www.globalreporting.org/standards/standards-development/sector-standard-for-mining/ (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Dashwood, H.S. The Rise of Global Corporate Social Responsibility: Mining and the Spread of Global Norms; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, J.R.; Kemp, D. Social licence and mining: A critical perspective. Resour. Policy 2013, 38, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Council on Mining and Metals (ICMM). Achieving No Net Loss or Net Gain of Biodiversity: Good Practice Guide. 2025. Available online: https://www.icmm.com/achieving-nnl-or-ng-biodiversity (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Bull, J.W.; Suttle, K.B.; Gordon, A.; Singh, N.J.; Milner-Gulland, E.J. Biodiversity offsets in theory and practice. Oryx 2013, 47, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilson, G. Corporate social responsibility in the extractive industries: Experiences from developing countries. Resources Policy 2012, 37, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). What Are the Sustainable Development Goals? United Nations: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2018; Available online: https://www.undp.org/sustainable-development-goals (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Boiral, O.; Heras-Saizarbitoria, I.; Brotherton, M.C. Sustainability management and social license to operate in the extractive industry: The cross-cultural gap with Indigenous communities. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 31, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, K. Indigenous rights and extractive resource projects: Negotiations over the policy and implementation of FPIC. Int. J. Hum. Rights 2017, 23, 880–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brueckner, M.; Eabrasu, M. Pinning down the social license to operate (SLO): The problem of normative complexity. Resour. Policy 2018, 59, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, N.L.; Lacey, J.; Carr-Cornish, S.; Dowd, A.-M. Social licence to operate: Understanding how a concept has been translated into practice in energy industries. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 86, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. UN General Assembly, A/RES/61/295. 2007. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/declaration-on-the-rights-of-indigenous-peoples.html (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Thorpe, M.A. Controversies of Consent: The Contradictory Uses of Indigenous Free, Prior, and Informed Consultation and Consent in Panama. Ph.D. Thesis, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutilier, R. Frequently asked questions about the social licence to operate. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2014, 32, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helwege, A. Challenges with resolving mining conflicts in Latin America. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2015, 2, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai, S.; Mehranvar, L.; Sander, J. Breaching Indigenous law: Canadian mining in Guatemala. Indig. Law J. 2007, 6, 31–66. Available online: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1267902 (accessed on 22 February 2025).

- Montoya, A. Post-extractive juridification: Undoing the legal foundations of mining in El Salvador. Geoforum 2023, 138, 103667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis. Laudato Si’: On Care for Our Common Home; Vatican Press: Vatican City, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Orientaciones Pastorales. Orientaciones Pastorales sobre los Impactos de la Minería en América Latina y el Caribe. 2025. Available online: https://www.vaticannews.va/es/iglesia/news/2025-07/orientaciones-pastorales-sobre-los-impactos-de-la-mineria.html (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- CooperAccion. El proyecto El Algarrobo y Tambogrande. 2024. Available online: https://cooperaccion.org.pe/opinion/el-proyecto-el-algarrobo-y-tambogrande/ (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Tico Times. Costa Rican seeks to re-legalize open-pit mining. The Tico Times, 28 November 2024. Available online: https://ticotimes.net/2024/11/28/costa-rican-seeks-to-re-legalize-open-pit-mining (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- The Guardian. El Salvador Overturns Metals Mining Ban, Defying Environmental Groups. The Guardian, 23 December 2024. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2024/dec/23/el-salvador-overturns-metals-mining-ban (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Meyer, J.W.; Rowan, B. Institutionalized organizations: Formal structure as myth and ceremony. Am. J. Sociol. 1977, 83, 340–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, T.; Preston, L.E. The stakeholder theory of the corporation: Concepts, evidence, and implications. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 65–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, B.; Kestler, A.; Anand, S. Building local legitimacy into corporate social responsibility: Gold mining firms in developing nations. J. World Bus. 2010, 45, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.K.; Agle, B.R.; Wood, D.J. Toward a theory of stakeholder identification and salience: Defining the principle of who and what really counts. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1997, 22, 853–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.K.; Lee, J.H.; Agle, B.R. Stakeholder prioritization work: The role of stakeholder salience in stakeholder research. In Stakeholder Management; Ricart, J.E., Ed.; Emerald Publishing: Leeds, UK, 2017; pp. 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridge, G. Contested terrain: Mining and the environment. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2004, 29, 205–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breakey, H.; Wood, G.; Sampford, C. Understanding and defining the social license to operate: Social acceptance, local values, overall moral legitimacy, and ‘moral authority’. Resour. Policy 2025, 102, 105488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemi, L.; Soares de Oliveira, R. Supporting Good Governance of Extractive Industries in Politically Hostile Settings: Rethinking Approaches and Strategies (Discussion Paper); Columbia Center on Sustainable Investment: New York, NY, USA, 2022; Available online: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/sustainable_investment/4 (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Szablowski, D. Struggles over extractive governance: Power, discourse, violence, and legality. Earth Syst. Gov. 2019, 1, 100011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods, 6th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez, S.A.; Barney, J.B.; Wuebker, R.J. Realism in the study of entrepreneurship. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2014, 39, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagg, S. Realism against legitimacy: For a radical, action-oriented political realism. Soc. Theory Pract. 2022, 48, 29–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, A.; Holzinger, I. Seeing through smoke and mirrors: A critical analysis of marketing CSR. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1915–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Ambiente de Panamá (MiAmbiente). Panamá se Consolida Como País Carbono Negativo; Ministerio de Ambiente de Panamá. 2025. Available online: https://dcc.miambiente.gob.pa/noticia-de-prueba2/ (accessed on 3 January 2025).

- Britannica. Panama: History, map, flag, capital, population, & facts. In Encyclopaedia Britannica; Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.: Chicago, IL, USA, 2025; Available online: https://www.britannica.com/place/Panama (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Intergovernmental Forum on Mining, Minerals, Metals and Sustainable Development (IGF). Mining Policy Framework Assessment: Panama (Assessment Report); International Institute for Sustainable Development: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2020; Available online: https://www.iisd.org/system/files/2021-02/panama-mining-policy-framework-assessment-en.pdf (accessed on 17 January 2025).

- Gómez, J. The mining moratorium in Panama: Economic impacts and social unrest. Lat. Am. Policy J. 2023, 12, 24–31. [Google Scholar]

- Dou, S.; Xu, D.; Zhu, Y.; Keenan, R. Critical mineral sustainable supply: Challenges and governance. Futures 2023, 146, 103101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 5th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Guest, G.; Namey, E.; Chen, M. A simple method to assess and report thematic saturation in qualitative research. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0232076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, R. Now I see it, now I don’t: Researcher’s position and reflexivity in qualitative research. Qual. Res. 2015, 15, 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Faircheallaigh, C.; Corbett, T. Indigenous participation in environmental management of mining projects: The role of negotiated agreements. Environ. Politics 2006, 14, 629–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CAMIPA. Factsheet: Mining in Panama; Cámara Minera de Panamá: Panama City, Panama, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Redwood, S. The mineral deposits of Panama: Arc metallogenesis on the trailing edge of the Caribbean Large Igneous Province. Boletín De La Soc. Geológica Mex. 2020, 72, A130220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, W.R. A theoretical framework for the investigation of the determinants of corporate environmental policy. Interdiscip. Environ. Rev. 2008, 10, 110–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, M. La Iglesia se Suma a Las Manifestaciones Contra la Explotación Minera en Panamá. Vida Nueva Digital, 21 October 2023. Available online: https://www.vidanuevadigital.com/2023/10/21/la-iglesia-se-suma-a-las-manifestaciones-contra-la-explotacion-minera-en-panama/ (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Rendon, J. Catholic Groups Call on Panama to Reverse Plan to Expand Mining. National Catholic Reporter, 16 February 2024. Available online: https://www.ncronline.org/earthbeat/justice/catholic-groups-call-panama-reverse-plan-expand-mining (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Bryant, P. Mining & Faith: Unexpected Partnerships for Prosperity. Clareo, 18 February 2015. Available online: https://clareo.com/mining-faith-unexpected-partnerships-for-prosperity/ (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- David, H.Y. La Pastoral Minera: Una respuesta de la Iglesia a los desafíos de la minería. In Conference on Formalization; Universidad Nacional de Piura: Piura, Peru, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Whiteman, G.; Mamen, K. Examining justice and conflict between mining companies and Indigenous peoples: Cerro Colorado and the Ngabe-Buglé in Panama. J. Bus. Manag. 2002, 8, 293–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prno, J.; Slocombe, D.S. A systems-based conceptual framework for assessing the determinants of a social license to operate in the mining industry. Environ. Manag. 2013, 51, 899–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Initiative for Responsible Mining Assurance (IRMA). IRMA Standard for Responsible Mining (Version 1.0). Section 2.2: Free, Prior and Informed Consent. 2018. Available online: https://responsiblemining.net/irma-standard (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Mining Association of Canada (MAC). Towards Sustainable Mining (TSM) Program. 2021. Available online: https://mining.ca/towards-sustainable-mining/ (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- International Council on Mining and Metals (ICMM). Performance Expectations. 2018. Available online: https://www.icmm.com/en-gb/our-principles/mining-principles/mining-principles (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Canario Guzmán, J.A.; Orlich, J.; Mendizábal-Cabrera, R.; Ying, A.; Vergès, C.; Espinoza, E.; Soriano, M.; Cárcamo, E.; Mendoza Marrero, E.R.; Sepúlveda, R.; et al. Strengthening research ethics governance and regulatory oversight in Central America and the Dominican Republic in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative study. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2022, 20, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dimension | SLO | FPIC | SLM (Proposed) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Objective | Community acceptance (voluntary) | Protection of Indigenous rights (legally mandated) | Broad-based, institutional and societal legitimacy |

| Primary Stakeholders | Local communities | Indigenous communities | All affected & influential actors, including state, civil society, industry |

| Legal/Normative Basis | Informal norm | International legal standard | Proposed governance framework grounded in legitimacy and multi-scalar inclusion |

| Target Scale | Project | Project & territorial | Institutional, regional, national levels |

| Engagement Mechanisms | Dialogue, benefit-sharing | Prior, informed consent | Continuous co-constructive governance and trust building |

| Temporal Focus | Reactive | Pre-approval consent | Forward-looking and adaptive |

| Inclusivity/Pluralism | Limited to local groups | Focuses on Indigenous rights holders | Multiple worldviews, institutions, and national publics |

| Procedural Mechanisms | Community agreements, monitoring | Consent procedures, standalone legal steps | Legitimacy thresholds, scenario planning, audits, cross-sector co-governance |

| Crisis Resilience | Firm-centric, lacks legal grounding, localized | Procedural insufficient in systemic crises | Co-produced, transparent, inclusive, justice-based decision-making |

| Institutional Trust Focus | Assumes stable institutions | Assumes legal enforcement | Centers credibility, accountability and systemic reform |

| Stakeholder Salience | Rarely explicit | Rarely explicit | Central: analyzes actor power, legitimacy, urgency |

| Category | Dimension | Focus | Illustrative Lines of Inquiry |

|---|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Anchors | Legitimacy Theory | Input/output/throughput legitimacy, institutional credibility | How do perceptions of fairness, process, and outcome shape legitimacy? What institutional conditions enable credible governance after crisis events? |

| Stakeholder Theory | Power asymmetries, plural expectations, inclusion | Which actors influence legitimacy beyond local communities? How do power imbalances affect governance co-production? | |

| Stakeholder Salience Theory | Power, legitimacy, urgency | How does stakeholder salience shift before and after crises? Which actors gain or lose influence in shaping outcomes? | |

| Political Ecology | Power relations, historical legacies, environmental justice | How do colonial histories or structural inequalities shape legitimacy challenges? What role do environmental justice narratives play? | |

| SLM Analytical Dimensions | Procedural Justice | Fairness, transparency, participation in decision-making | How inclusive and respectful are governance processes? Do stakeholders perceive having a meaningful voice? |

| Institutional Trust | Confidence in state/corporate actors’ integrity and competence | What factors shape the rebuilding of trust after a crisis? How do historical grievances impact current trust-building? | |

| Epistemic Legitimacy | Recognition and validation of diverse knowledge systems | Whose knowledge (Indigenous, scientific, local) is valued as authoritative? How are power relations embedded in these validations? | |

| Relational Governance | Ongoing trust-building, adaptive stakeholder networks | How do interactive engagements transform stakeholder relationships? What enables adaptive and dialogic governance? | |

| Contextual Lenses | Multi-scalarity | Local, national, and global legitimacy | How do local grievances escalate to broader legitimacy crises? What mechanisms can bridge scale disconnects in governance? |

| Temporality | Historical context, forward-looking adaptation | How do past governance failures shape present legitimacy dynamics? How can governance anticipate future legitimacy challenges? |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Eddine, C. Society and Mining: Reimagining Legitimacy in Times of Crisis—The Case of Panama. Mining 2025, 5, 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/mining5040072

Eddine C. Society and Mining: Reimagining Legitimacy in Times of Crisis—The Case of Panama. Mining. 2025; 5(4):72. https://doi.org/10.3390/mining5040072

Chicago/Turabian StyleEddine, Chafika. 2025. "Society and Mining: Reimagining Legitimacy in Times of Crisis—The Case of Panama" Mining 5, no. 4: 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/mining5040072

APA StyleEddine, C. (2025). Society and Mining: Reimagining Legitimacy in Times of Crisis—The Case of Panama. Mining, 5(4), 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/mining5040072