Aleppo Pixelated: An Urban Reading through Digitized Historical Maps and High-Resolution Orthomosaics Case Study of al-ʿAqaba and al-Jallūm Quarters

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. State-of-the-Art

3. Materials and Methods

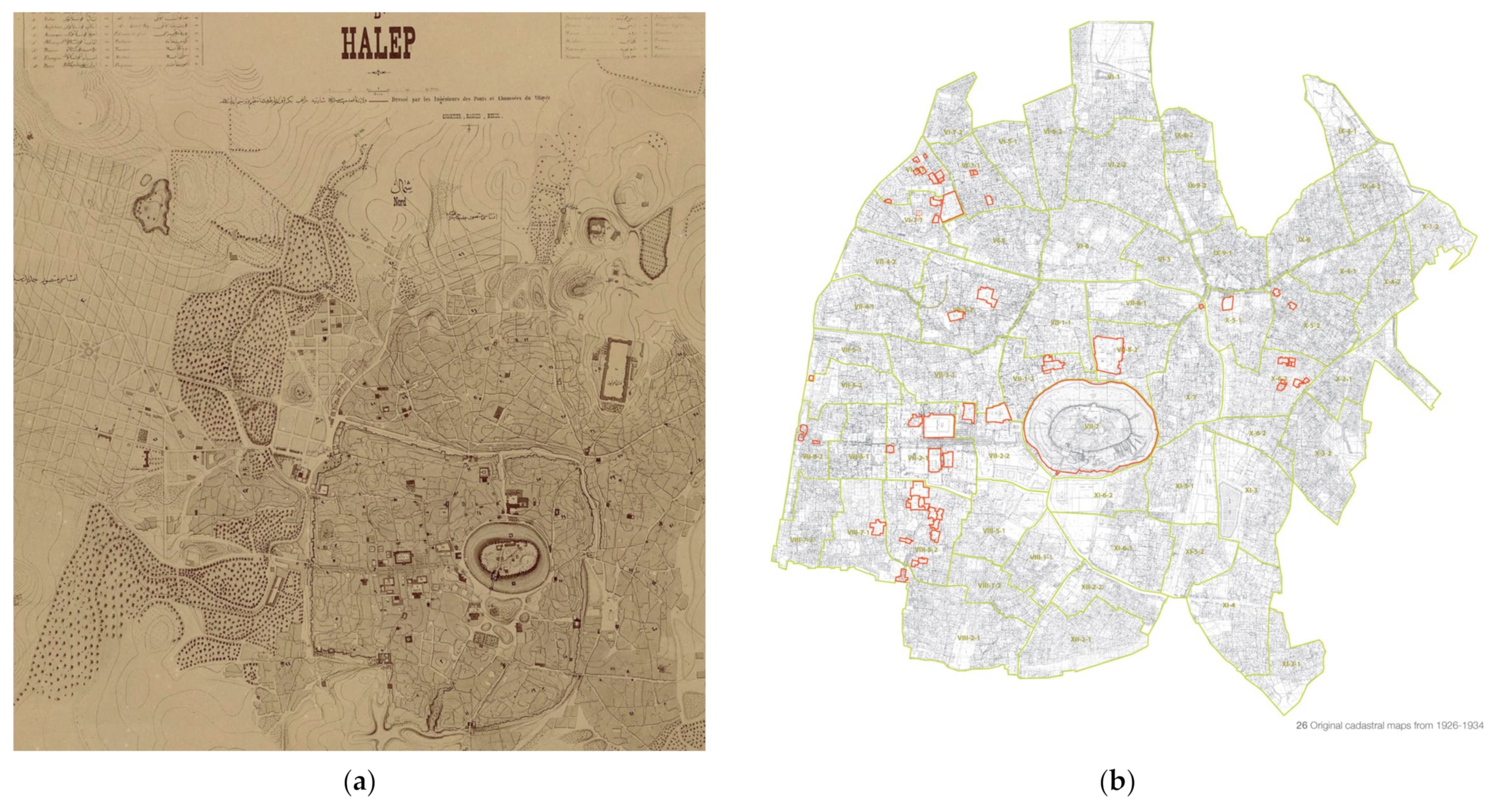

| Map Name | Date | Scale | Accuracy | Origin | Method of Acquisition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Ottoman map | 18th | 1:5000 | There is a noticeable deviation in the linearity of streets. | The Ottoman Road and Bridges Engineers | Possibly made through topographic surveys. |

| The French cadastral maps | 1930s | No available information. | A team headed by C. Duraffourd [21] | Topographic Surveys. | |

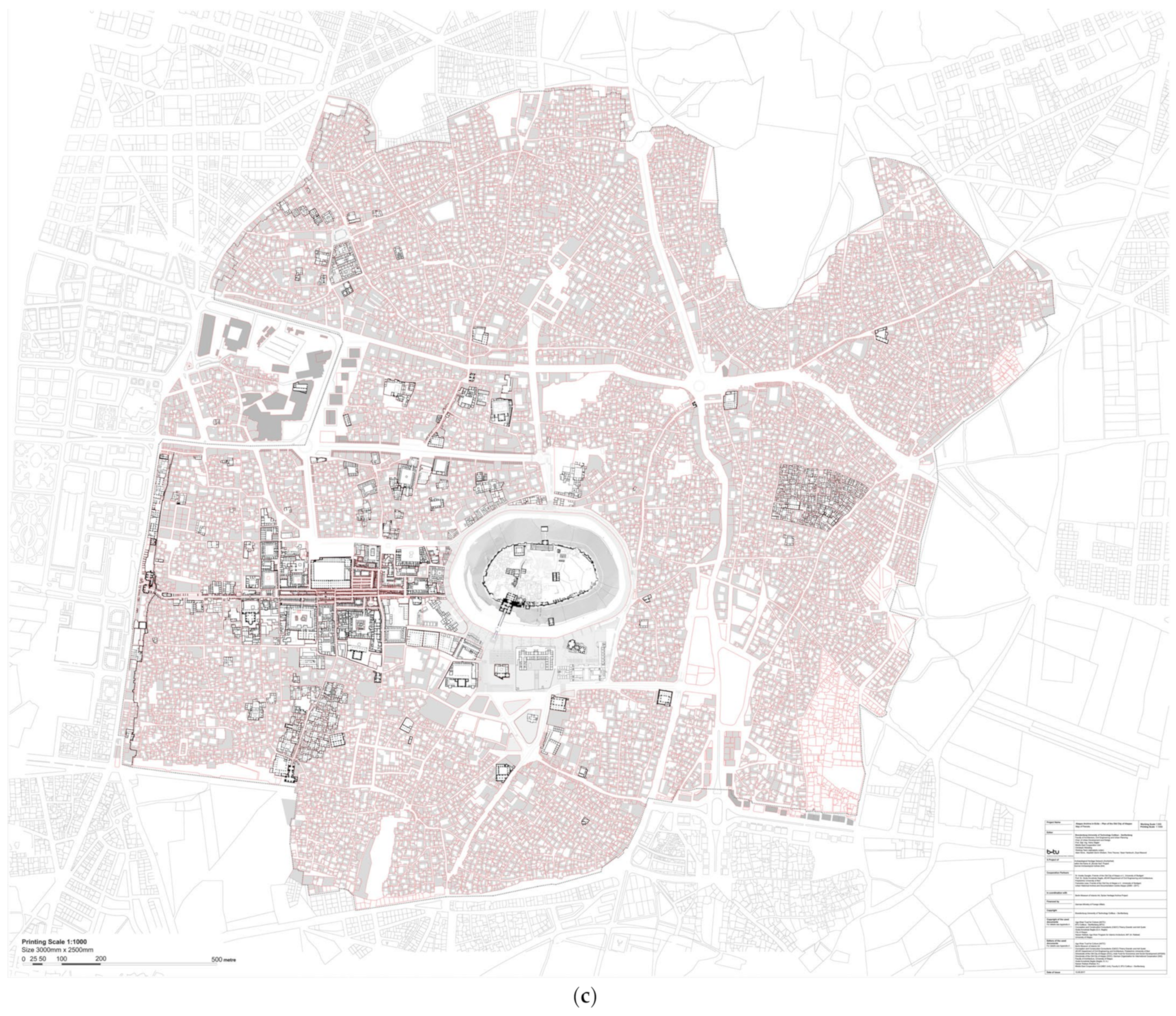

| Aleppo Archive in Exile—Plan of the Old City of Aleppo | 2017 | 1:1000 | No available information. | The Brandenburg University of Technology (BTU) [28] | Combination of the following survey maps of Aleppo: 1-Aleppo Cadastral Plan. In Syrian Heritage Archive Project. Adapted from DOC, GIZ (eds.) (1997–1998) Digitized Cadastral Plan of Aleppo based on French Cadastral Plans of Old Aleppo (1926–1930). 2-Directorate of the Old City of Aleppo (ed.) Aleppo Cadastral Plan with Courtyard. Urban Historical Archive and Documentation Center for Aleppo. |

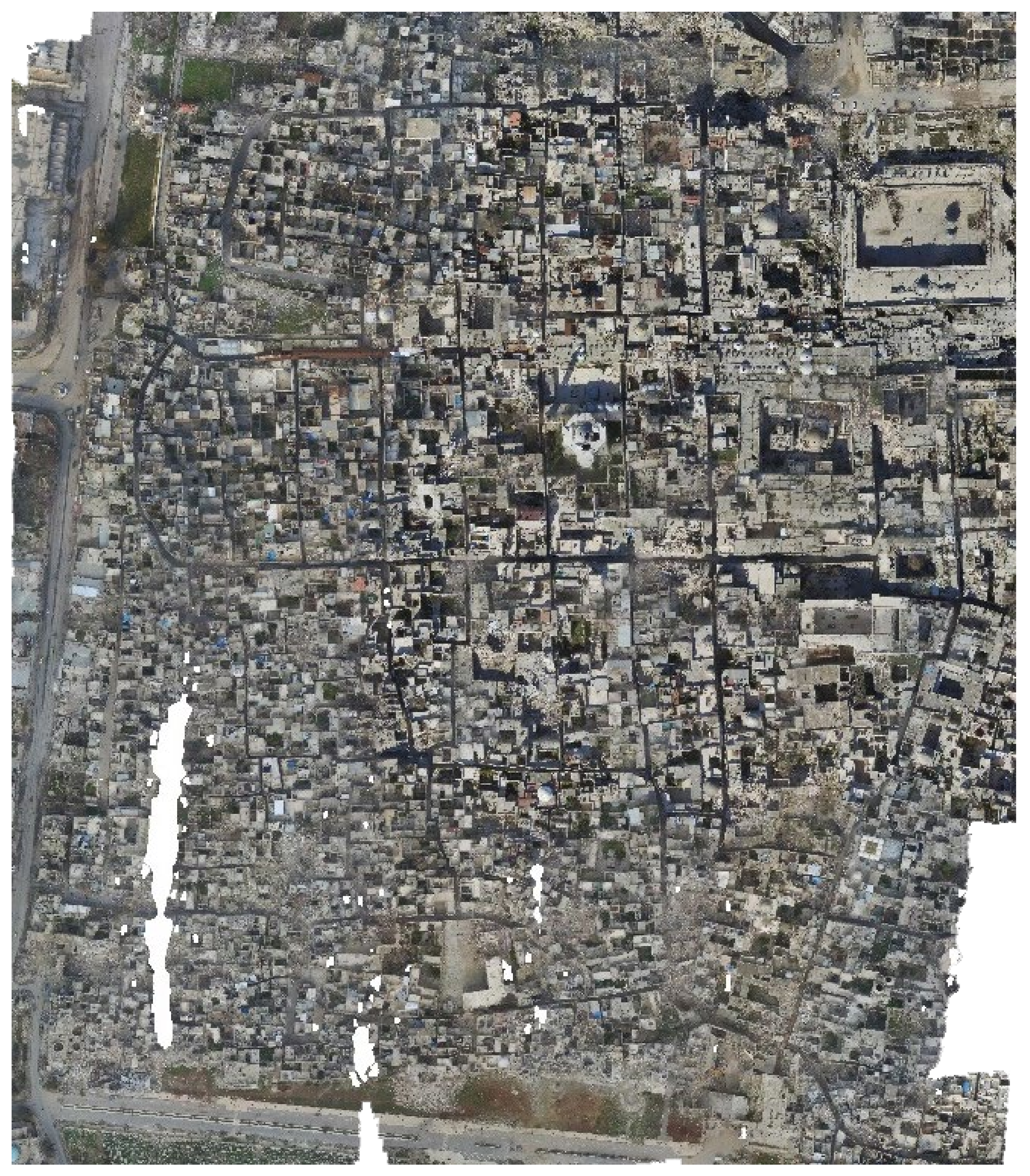

| Digital Orthomosaics | 2018 | 1:1 | 1:1 ± 20 cm | The Author | Laser scanning and Aerial Photogrammetry |

3.1. Digital Workflow and Methodology

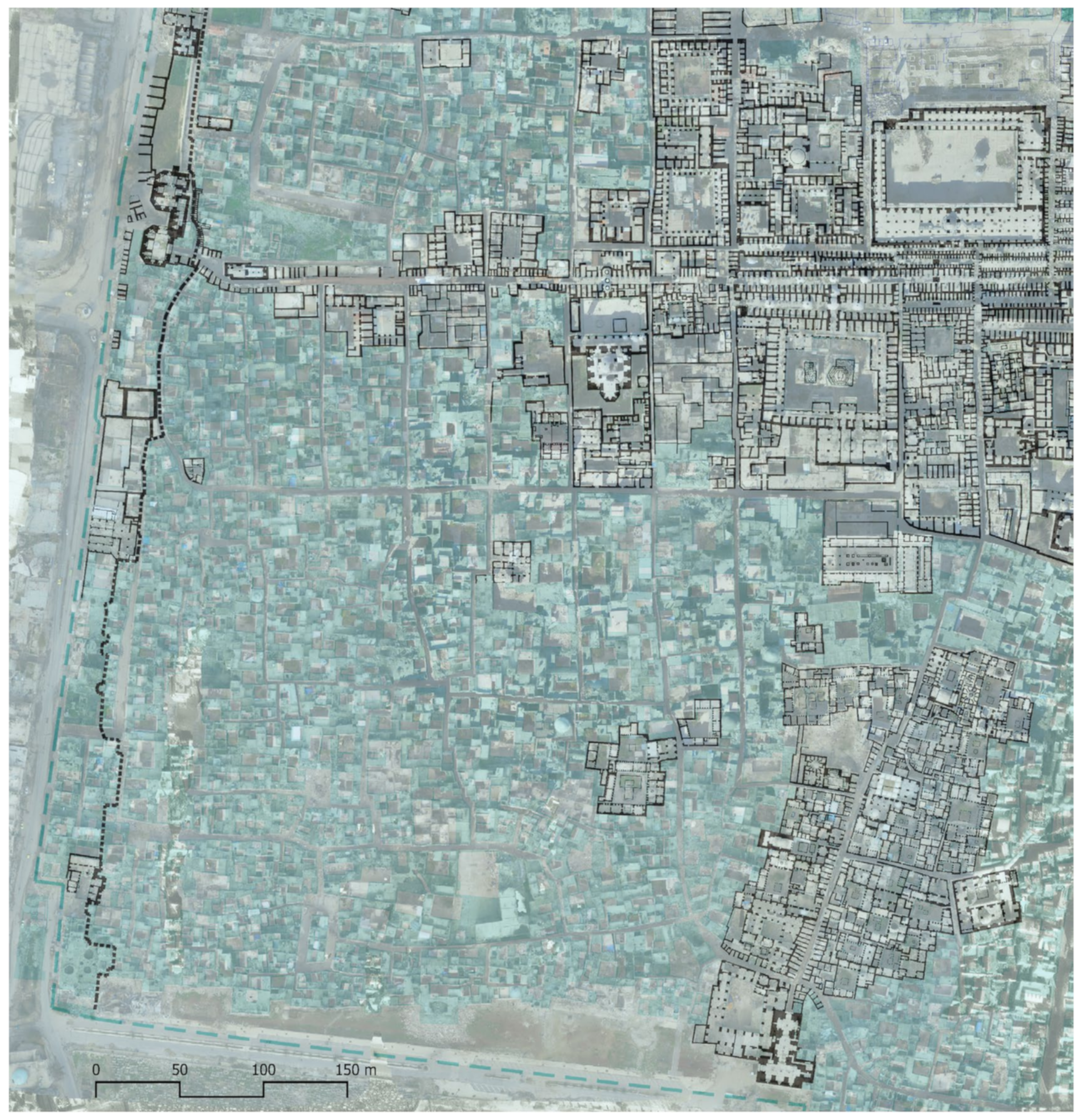

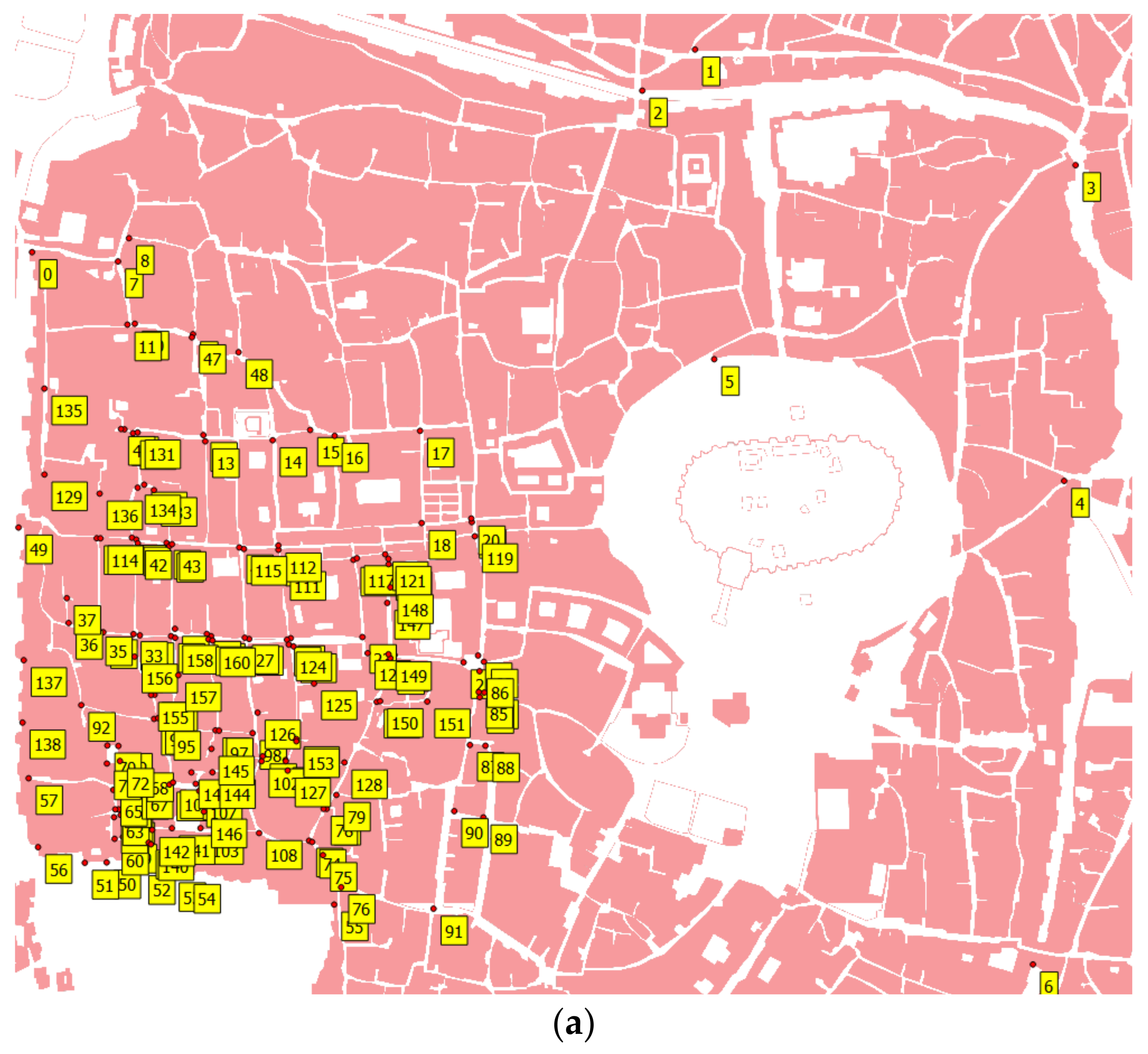

3.2. Hybrid Point Cloud Acquisition and Processing

3.3. Aligning, Geo-Referencing and Superimposing Datasets

4. Results

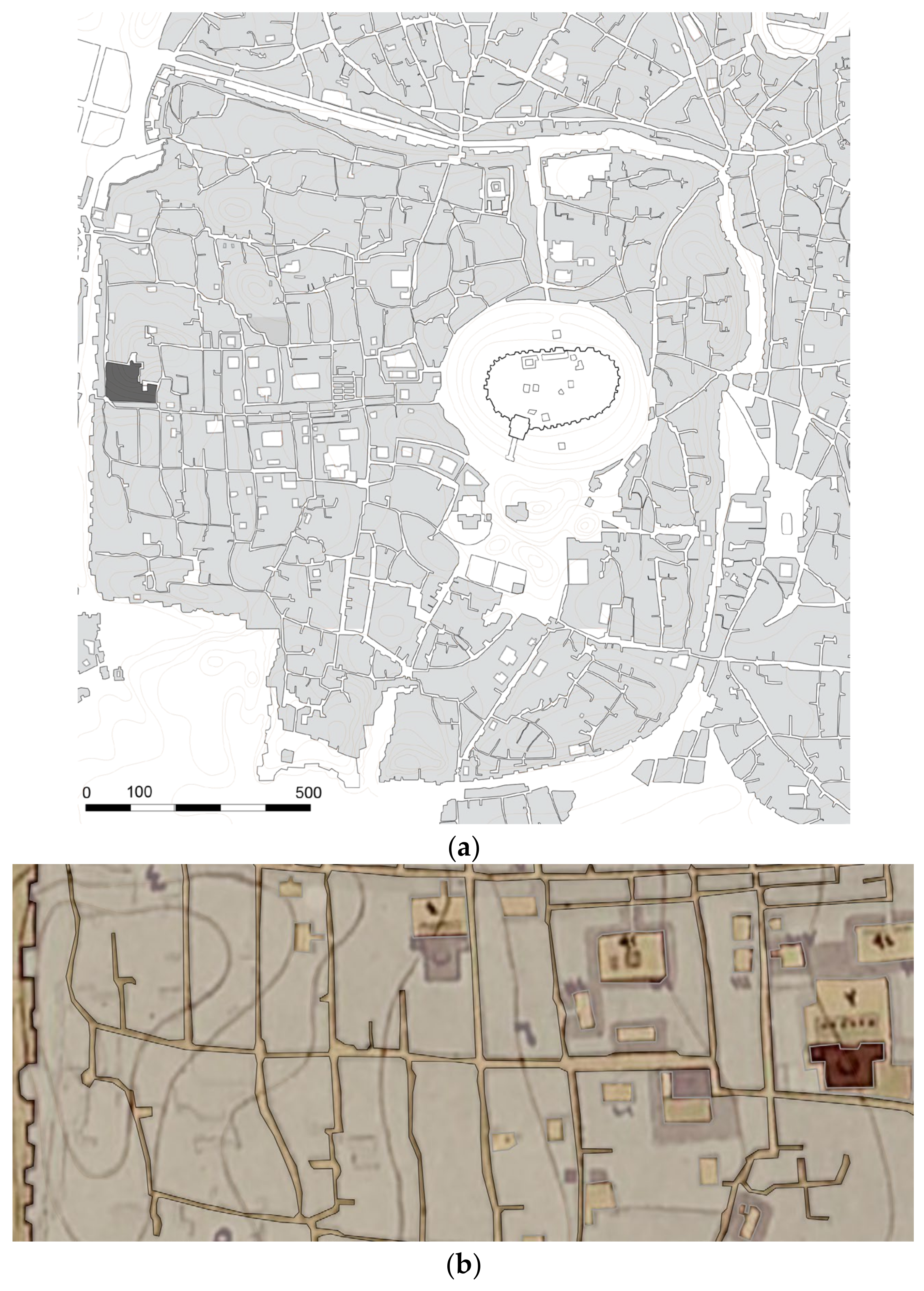

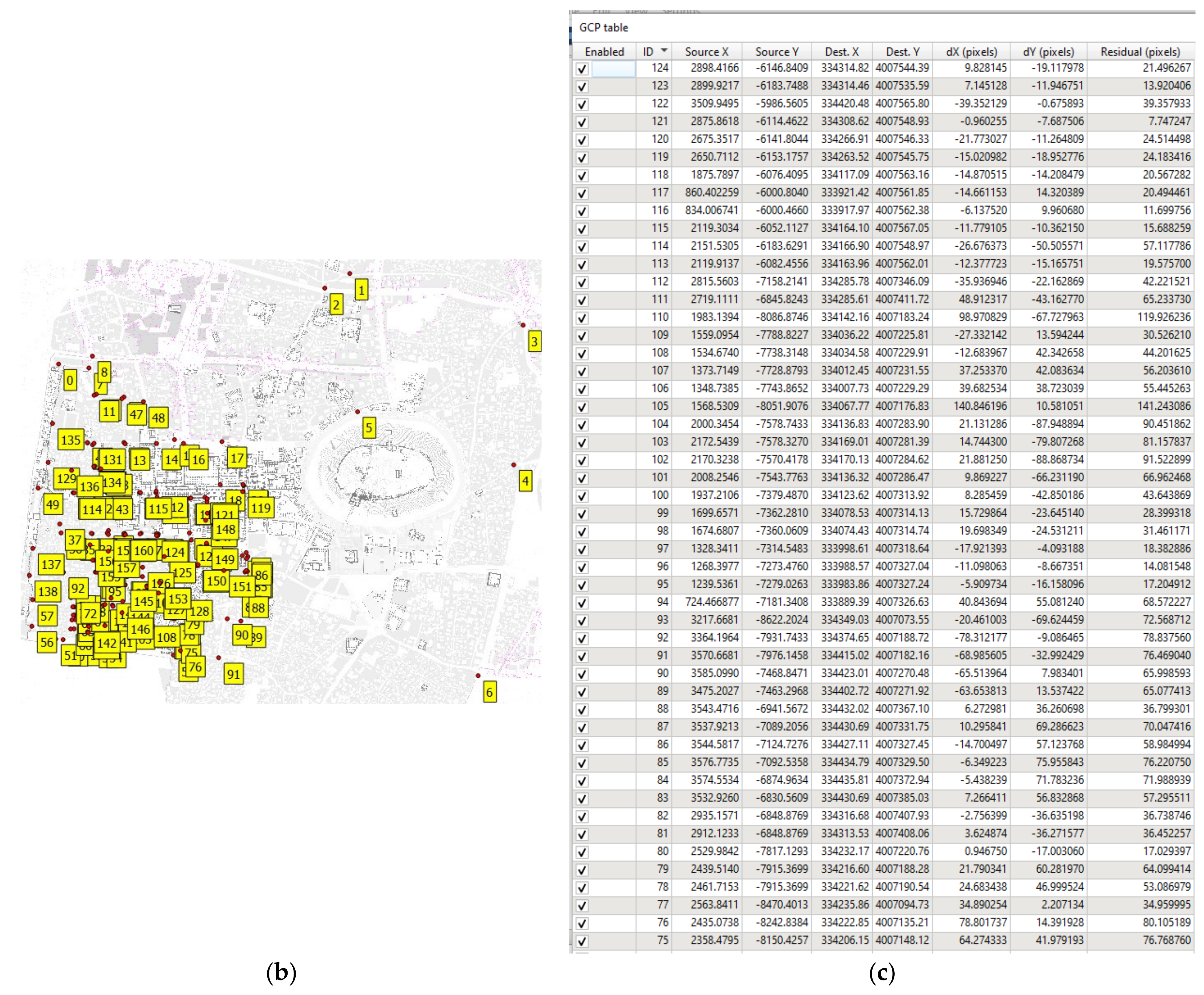

- The addition of cul-de-sac streets or new streets: The layout of the cul-de-sac streets is mostly preserved, particularly those located behind the city walls. However, there are two notable differences when comparing the modern map to the historical one. Firstly, the street directly behind the walls of the city (Figure 7, number 1) was a cul-de-sac that was extended until Bāb Antakiya. The perpendicular street (Figure 7, number 4) was also extended to meet the street parallel to the wall (Figure 7, number 1). Other cul-de-sac streets that were extended are visible in Figure 7, number 3, 28. However, street number 28 can either be a cul-de-sac that was converted to a street, or this representation could mean that the existing covered section of the street named “Ṣibāṭ Sūdān” was extending further.

- New streets also emerged further separating the fabric (Figure 7, number 5, 6). Street 2 which is the wide street leading towards the higher elevation of al-ʿAqaba (Figure 7, number 2) is not visible in the Ottoman map. However, it seems unlikely that it did not exist due to the different elevations around its sides and the fact that it borders an open space number (20). At al-Shūʽaybiyya Mosque (Figure 6b, number 4), two streets diverge from each other (Figure 7, below area 20), which is only represented in the modern map.

- The new streets and the extended cul-de-sac streets resulted in separating several insulae, especially the section of Tallet al-ʿAqaba behind the wall. It was separated into six distinct blocks that also accommodated high-rise buildings despite its initial advantageous elevation. Another division of blocks is visible around streets numbers 8, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 16,18, and 22. While added cul-de-sac streets can be observed in Figure 7, numbers 7, 9, 17, 21, 23, 24, 25, 26, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, and 34. Street number 27 represents a unique example of a street that does not correspond to a modern street. It is possible that it is another surveying error, and this street was the one directly behind the western walls of the city.

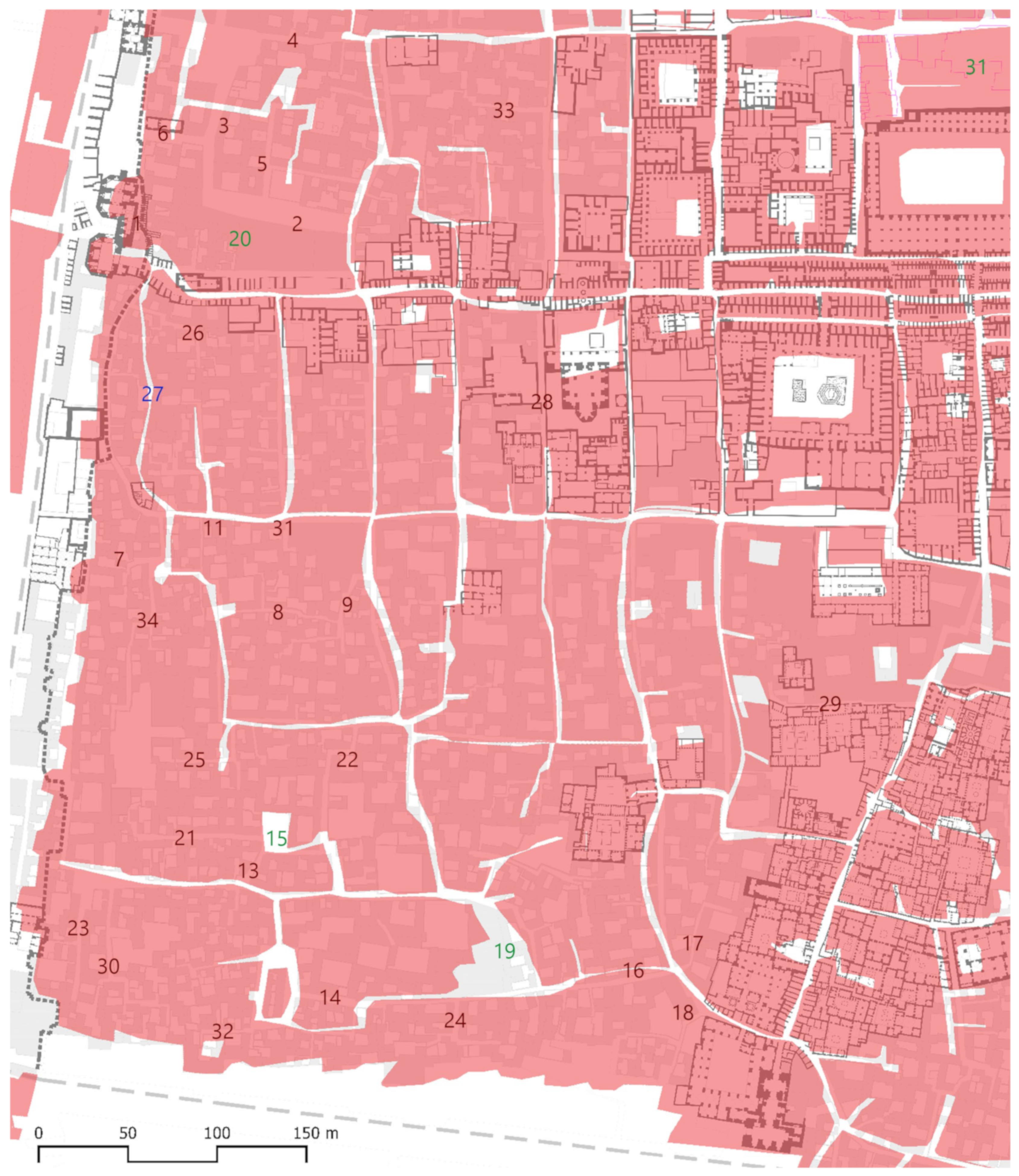

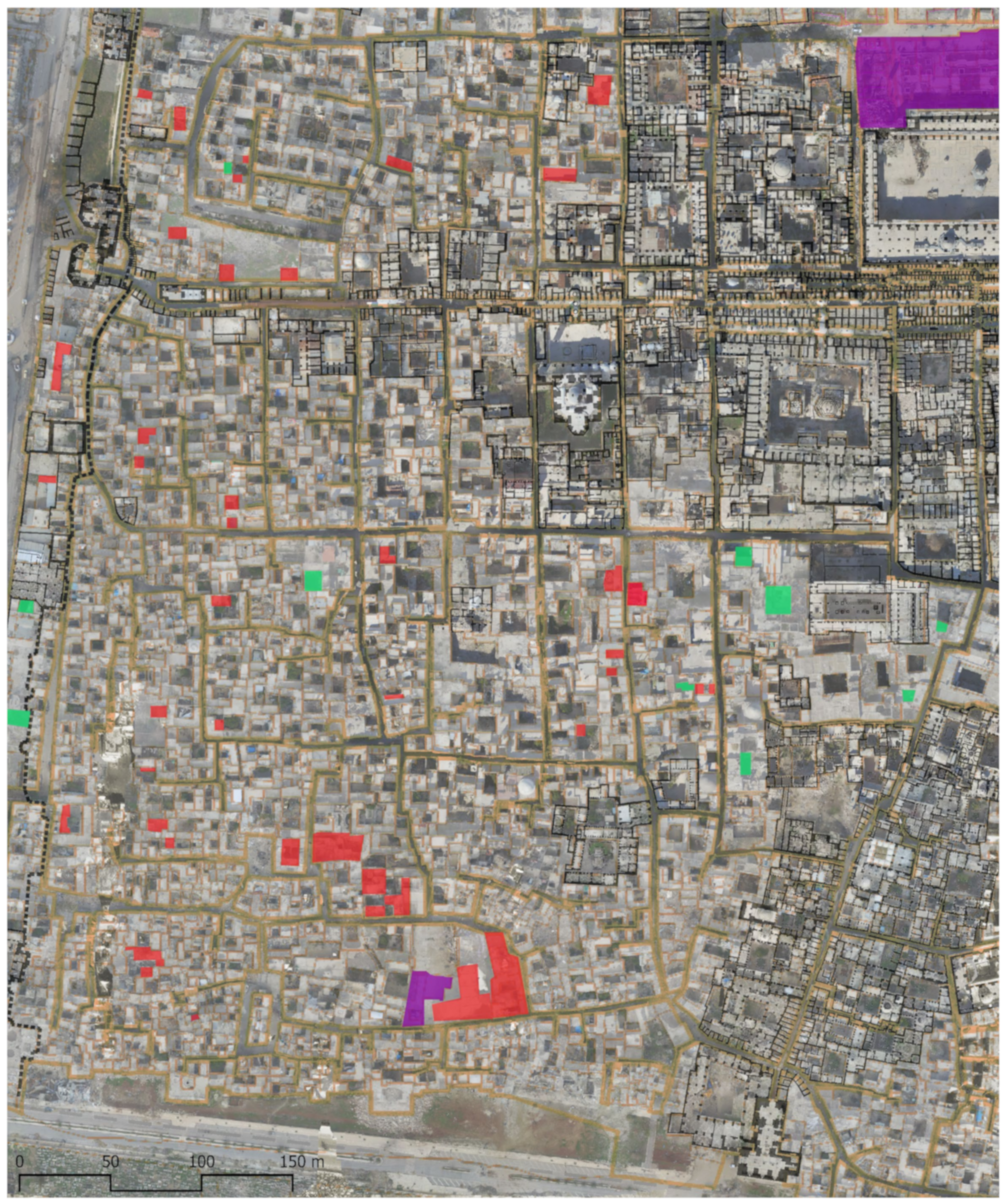

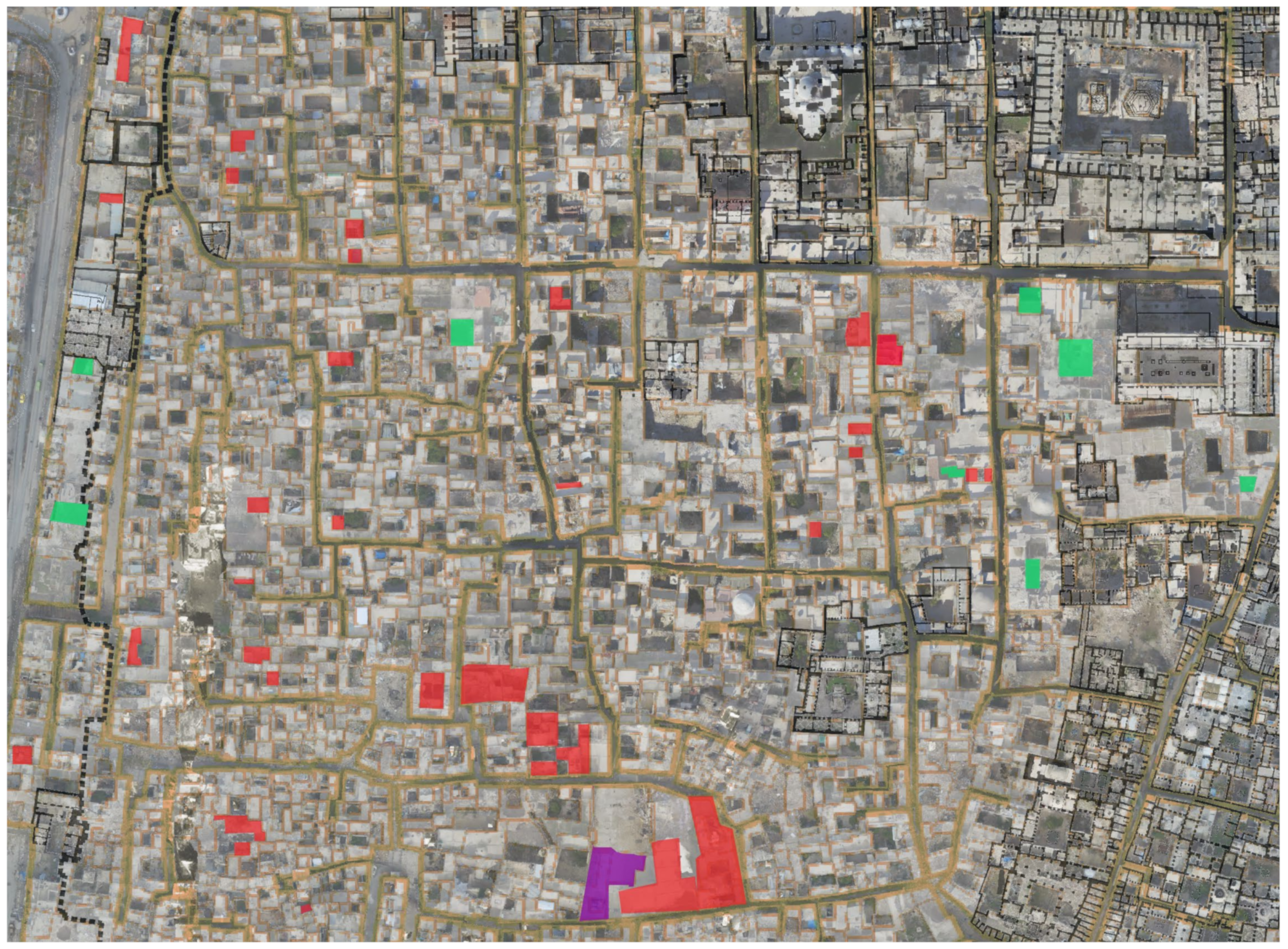

- The division or the removal of courtyards: In Figure 7, there are some noticeable differences regarding the size, and number of courtyards. Specifically, the number and size of courtyards have decreased possibly due to division of the family house into smaller units to accommodate the families of the children or the change of the residential function. Adding another layer from the cadaster map of the 1930s (Figure 8) reveals additional information compared to the survey results regarding the changes in the size and distribution of open spaces and courtyards. In Figure 8 and Figure 9, courtyards marked with red have been subject to alteration, division, and or covering. On the other hand, courtyards that were not observed in the BTU map and the French cadaster are marked in light green.

- The addition of buildings within a previously open space: Two open spaces were built partially, space number 20 and space 19, where a public school and some residential parcels were added (Figure 7 and Figure 8). Space number 15 remained the same. Unfortunately, the Ottoman map does not contain additional information about the courtyards, which hinders a complete analysis of the changes in the open spaces.

- The removal of buildings to create an open space: This change is only observed in two locations. The first one is the square in front of the Umayyad Mosque and the other is the removal of a small section of residential buildings to accommodate the yard of the public school (Figure 7, space 19). Both changes are marked in purple in (Figure 8 and Figure 9).

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions and Outlook

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Burns, R. Cities of The Ancient World—Aleppo: A History; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Nigro, L. Yamkhad/Aleppo: Investigating the Second Millennium B.C. Capital of Northern Syria Through Islamic, Byzantine and Classical Towns. Environ. Des. J. Islam. Environ. Des. Res. Cent. 1999, 2, 46–55. [Google Scholar]

- Petrie, G. Airborne Photogrammetric Mapping. In The Routledge Handbook of Geospatial Technologies and Society; Routledge: London, UK, 2023; pp. 202–225. [Google Scholar]

- Lemmens, M. Airborne and Ground-based Laser Scanning. In The Routledge Handbook of Geospatial Technologies and Society; Routledge: London, UK, 2023; pp. 171–187. [Google Scholar]

- Balsa-Barreiro, J.; Fritsch, D. Generation of visually aesthetic and detailed 3D models of historical cities by using laser scanning and digital photogrammetry. Digit. Appl. Archaeol. Cult. Herit. 2018, 8, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwardhi, D.; Trisyanti, S.W.; Virtriana, R.; Syamsu, A.A.; Jannati, S.; Halim, R.S. Heritage Smart City Mapping, Planning and Land Administration (Hestya). ISPRS Int. J. Geo Inf. 2022, 11, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maragkogiannis, K.; Kolokotsa, D.; Konstantaras, A. Combining terrestrial laser scanning and computational fluid dynamics for the study of the urban thermal environment. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2014, 13, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, A.V.; Laefer, D.F.; Smolic, A.; Zolanvari, S.I. Per-point processing for detailed urban solar estimation with aerial laser scanning and distributed computing. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2019, 155, 119–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serna, A.; Marcotegui, B. Urban accessibility diagnosis from mobile laser scanning data. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2013, 84, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepe, M.; Costantino, D.; Alfio, V.S.; Angelini, M.G.; Garofalo, A.R. CityGML Multiscale Approach for the Conservation and Management of Cultural Heritage: The Case Study of the Old Town of Taranto (Italy). Int. J. Geo Inf. 2020, 9, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipriani, L.; Bertacchi, S.; Bertacchi, G. An optimised workflow for the interactive experience with cultural heritage through reality-based 3D models: Cases study in archaeological and urban complexes. In Proceedings of the GEORES 2019—2nd International Conference of Geomatics and Restoration, Milan, Italy, 8–10 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Wen, C.; Dai, Y.; Yu, S.; Liu, M. Urban 3D modeling using mobile laser scanning: A review. Virtual Real. Intell. Hardw. 2020, 2, 175–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papa, L.M. Considerations about Old Maps in the Digital Era. Disegno 2019, 5, 91–102. [Google Scholar]

- Talich, M. Digitization of Old Maps and Possible On-line Tools for Their Use. In Digital Cultural Heritage; Kremers, H., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 331–341. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, S.; Shen, D. A Study of Historical Urban Landscape Layering in Luoyang. Land 2023, 12, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cybulski, P.; Wielebskil, Ł.; Medyńska-Gulij, B.; Lorek, D.; Horbiński, T. Spatial visualization of quantitative landscape changes in an industrial region between 1827 and 1883. Case study Katowice, southern Poland. J. Maps 2020, 16, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Aga Khan Trust for Culture. Old City of Aleppo: Building Information and Preliminary Damage Assessment; The Aga Khan Trust for Culture: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- The Aga Khan Trust for Culture. Plan of Reconstruction and Recovery of the Ancient City of Aleppo: Strategy and Proposed Restoration Projects; The Aga Khan Trust for Culture: Salamiyah, Syria, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Raymond, A. Aux origines du plan d’Alep par Rousseau: Le plan de Vincent Germain de 1811. In The Ottoman Empire and Its Heritage, Politics, Society and Economy, Syria and Bilad Al-Sham under Ottoman Rule; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2010; Volume 43, pp. 499–512. [Google Scholar]

- Stürzbecher, K.; Windelberg, J.; Abdul Aziz Hallaj, O. (Eds.) Rehabilitation of the Old City of Aleppo, Development Plan for the Old City of Aleppo; GTZ: Aleppo, Syria, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Gaube, H.; Wirth, E. Aleppo: Historische und Geographische Beiträge zur Baulichen Gestaltung, zur Sozialen Organisation und zur Wirtschaftlichen Dynamik Einer Vorderasiatischen Fernhandelsmetropole—Karten; Dr. Ludwig Reichert: Wiesbaden, Germany, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- David, J.-C.; Boissière, T. (Eds.) Alep et Ses Territoires, Fabrique et Politique D’une Ville (1868–2011); Presses de l’Ifpo, Institut Français du Proche-Orient: Beyrouth, Lebanon, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sauvaget, J. Alep Essai Sur le Développement d’une Grande Ville Syrienne, des Origines au Milieu du XIX Siècle; Librairie Orientaliste Paul Geuthner: Paris, France, 1941. [Google Scholar]

- Neglia, G.A. Aleppo: Processes of Formation of the Medieval Islamic City; Poliba Press: Bari, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Neglia, G.A. Persistences and Changes in The Urban Fabric of The Old City of Aleppo. Environ. Des. J. Islam. Environ. Des. Cent. 2001, 1–2, 32–41. [Google Scholar]

- Raghid, B. Plan Général de la Ville d’Halep Dressé par les Ingénieurs des Ponts et Chaussées du Vilayet Chartier. National Library of France. Available online: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b52507324h/f3.item.zoom (accessed on 26 August 2023).

- The Aleppo Archive. A Place for the Memory of Urban History; The Aleppo Archive: Aleppo, Syria, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zarrin Ghalam, S.; Wessling, C. Making the Past Visible for the Future: Map of the Old City of Aleppo. In The UNESCO Memory of the World Programme; Edmondson, R., Jordan, L., Prodan, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Orabi, R. Challenges of Applying Reality Capturing Methods in a Post-Conflict Urban Context: The Digital Survey in the Old City of Aleppo. In Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on Cultural Heritage and New Technologies, Vienna, Austria, 2–4 November 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Archnet. Écochard: Aleppo Album. Available online: https://www.archnet.org/collections/151?media_content_id=91326. (accessed on 16 January 2019).

- USGS Earth Resources Observation and Science (EROS) Center. USGS EROS Archive—Declassified Data—Declassified Satellite Imagery—1. 13 July 2018. Available online: https://www.usgs.gov/centers/eros/science/usgs-eros-archive-declassified-data-declassified-satellite-imagery-1?qt-science_center_objects=0#qt-science_center_objects (accessed on 13 January 2024).

- Ibn, K.; Al-Ghazzī, H.; Shaath, S.; Fakhuri, M. Nahr Al-Dzahab fī Tarīkh Ḥalab; Maronite Printing House: Aleppo, Syria, 1991; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Ibn, K. Al-‘Ajamī, Kunūz Al-Dzahab fī Tarīkh Ḥalab; Bakkūr, S.S.F., Ed.; Dar Al-Qalam al-‘Arabī: Aleppo, Syria, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- David, J.-C. Valorisation du patrimoine mondial alépin, Valeur d’usage et référence identitaire, attraction touristique, vitrine du nouveau centre. In Alep et Ses Territoires: Fabrique et Politique D’une Ville (1868–2011); Presses de l’Ifpo: Beyrouth, Lebanon, 2014; pp. 393–417. [Google Scholar]

- De la Croix, H. Military Architecture and the Radial City Plan in Sixteenth Century Italy. Art Bull. 1960, 42, 263–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Orabi, R. Aleppo Pixelated: An Urban Reading through Digitized Historical Maps and High-Resolution Orthomosaics Case Study of al-ʿAqaba and al-Jallūm Quarters. Digital 2024, 4, 152-168. https://doi.org/10.3390/digital4010007

Orabi R. Aleppo Pixelated: An Urban Reading through Digitized Historical Maps and High-Resolution Orthomosaics Case Study of al-ʿAqaba and al-Jallūm Quarters. Digital. 2024; 4(1):152-168. https://doi.org/10.3390/digital4010007

Chicago/Turabian StyleOrabi, Rahaf. 2024. "Aleppo Pixelated: An Urban Reading through Digitized Historical Maps and High-Resolution Orthomosaics Case Study of al-ʿAqaba and al-Jallūm Quarters" Digital 4, no. 1: 152-168. https://doi.org/10.3390/digital4010007

APA StyleOrabi, R. (2024). Aleppo Pixelated: An Urban Reading through Digitized Historical Maps and High-Resolution Orthomosaics Case Study of al-ʿAqaba and al-Jallūm Quarters. Digital, 4(1), 152-168. https://doi.org/10.3390/digital4010007