The Role of Microglial Activation in the Pathogenesis of Drug-Resistant Epilepsy: A Systematic Review of Clinical Studies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Protocol

2.2. Sources of Data Collection and Search Strategy

2.3. Search Content

2.4. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.5. Population

2.6. Intervention/Exposure

2.7. Comparison

2.8. Outcome

2.9. Data Extraction

2.10. Level of Evidence

2.11. Quality Assessment

2.12. Risk of Bias Assessment

3. Results

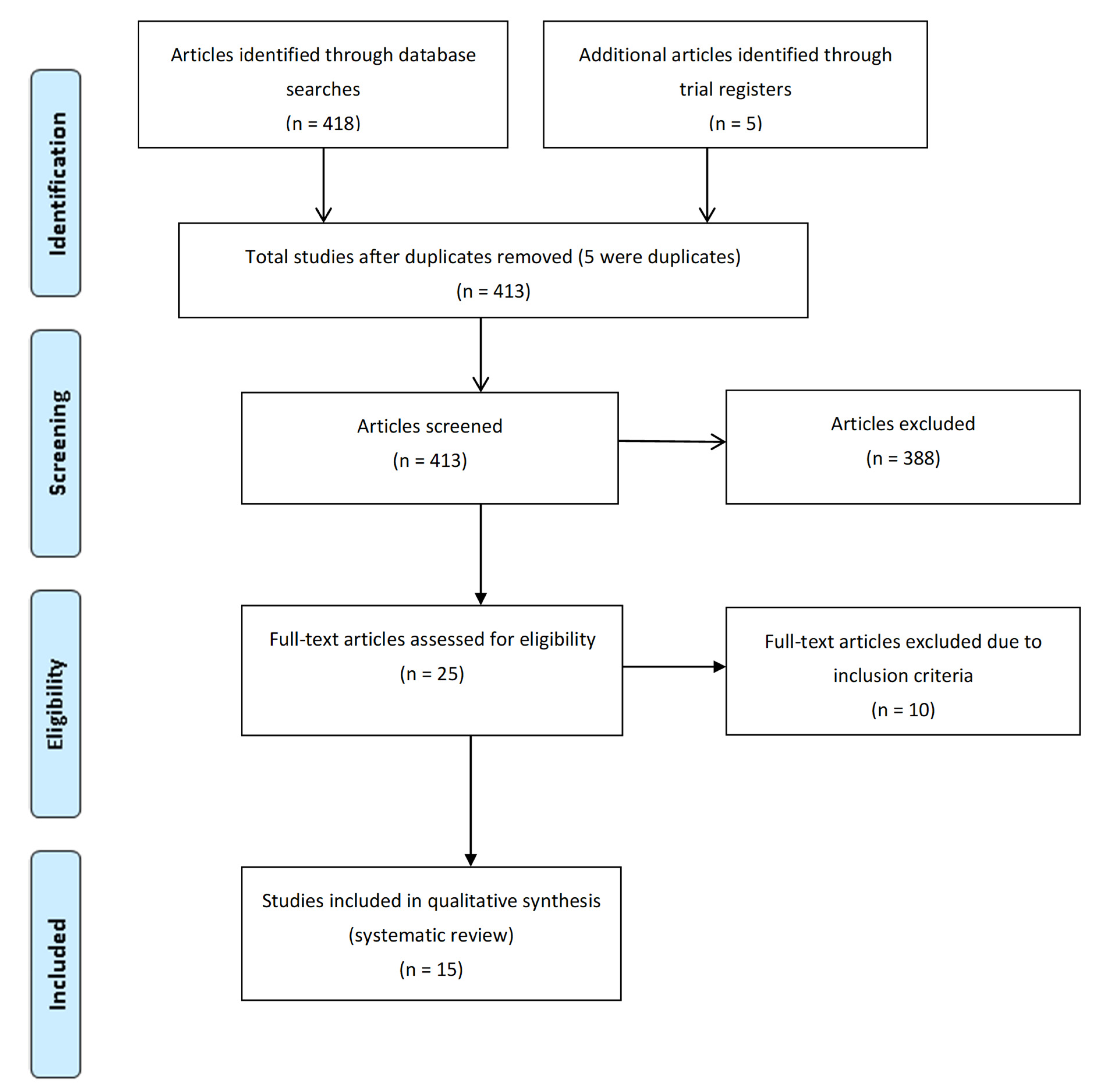

3.1. Literature Search

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Risk of Bias Assessment

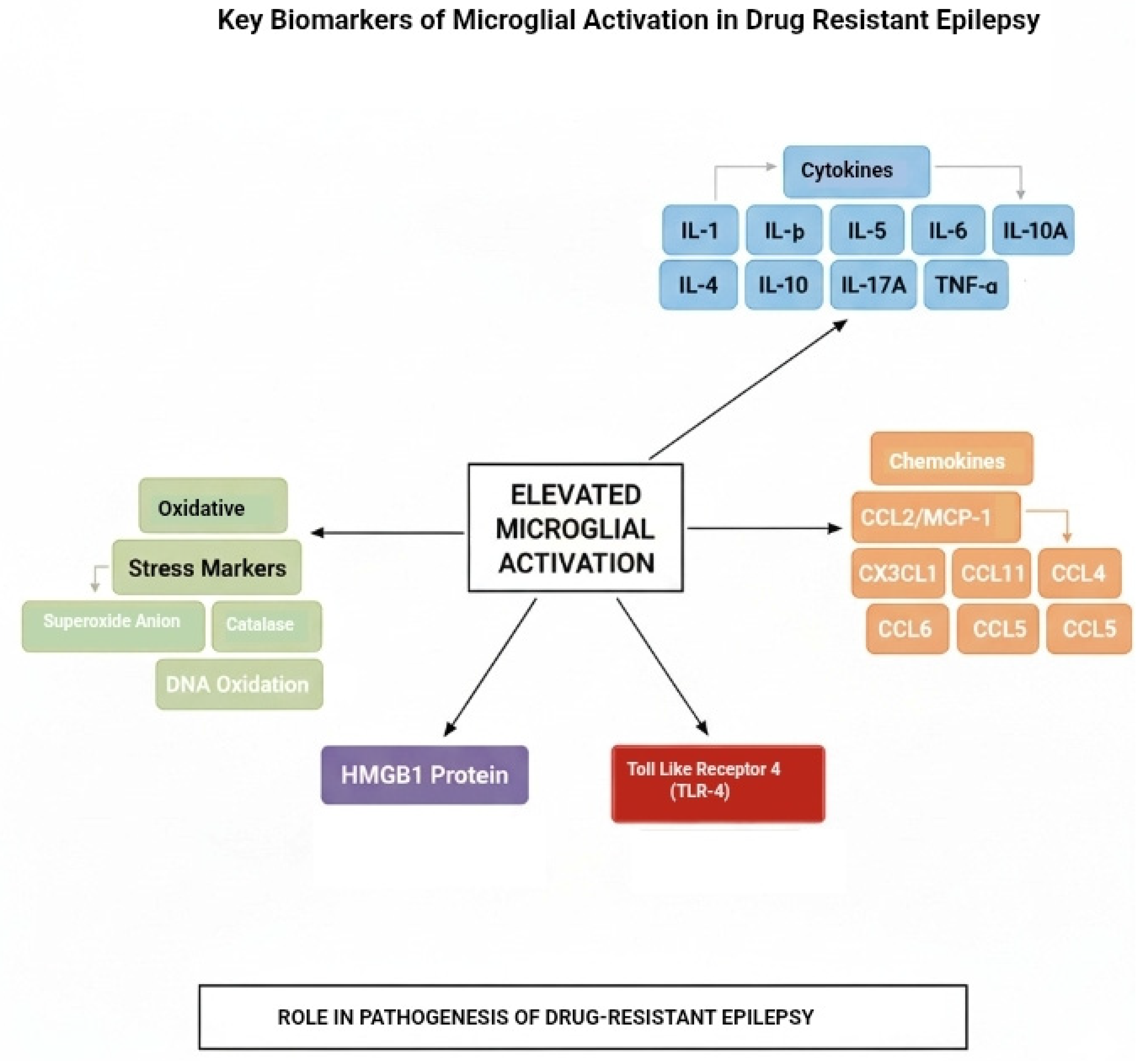

3.4. Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines

3.5. Chemokines

3.6. Oxidative Stress Markers

3.7. High Mobility Group Box 1 (HMGB1) Protein

3.8. Toll-Like Receptor 4 (TLR-4)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brodie, M.J.; Zuberi, S.M.; Scheffer, I.E.; Fisher, R.S. The 2017 ILAE classification of seizure types and the epilepsies: What do people with epilepsy and their caregivers need to know? Epileptic Disord. 2018, 20, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Sander, J.W. The global burden of epilepsy report: Implications for low- and middle-income countries. Epilepsy Behav. 2020, 105, 106949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwan, P.; Arzimanoglou, A.; Berg, A.T.; Brodie, M.J.; Allen Hauser, W.; Mathern, G.; Moshé, S.L.; Perucca, E.; Wiebe, S.; French, J. Definition of drug resistant epilepsy: Consensus proposal by the ad hoc Task Force of the ILAE Commission on Therapeutic Strategies. Epilepsia 2010, 51, 1069–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwan, P.; Brodie, M.J. Early Identification of Refractory Epilepsy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000, 342, 314–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-Bedolla, P.; Feria-Romero, I.; Orozco-Suárez, S. Factors not considered in the study of drug-resistant epilepsy: Drug-resistant epilepsy: Assessment of neuroinflammation. Epilepsia Open 2022, 7 (Suppl. 1), S68–S80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiragi, T.; Ikegaya, Y.; Koyama, R. Microglia after seizures and in epilepsy. Cells 2018, 7, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victor, T.R.; Tsirka, S.E. Microglial contributions to aberrant neurogenesis and pathophysiology of epilepsy. Neuroimmunol. Neuroinflamm. 2020, 7, 234–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devinsky, O.; Vezzani, A.; Najjar, S.; De Lanerolle, N.C.; Rogawski, M.A. Glia and epilepsy: Excitability and inflammation. Trends Neurosci. 2013, 36, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viviani, B.; Bartesaghi, S.; Gardoni, F.; Vezzani, A.; Behrens, M.M.; Bartfai, T.; Binaglia, M.; Corsini, E.; Di Luca, M.; Galli, C.L.; et al. Interleukin-1β enhances NMDA receptor-mediated intracellular calcium increase through activation of the Src family of kinases. J. Neurosci. 2003, 23, 8692–8700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vezzani, A.; Friedman, A. Brain inflammation as a biomarker in epilepsy. Biomark. Med. 2011, 5, 607–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiffert, E.; Dreier, J.P.; Ivens, S.; Bechmann, I.; Tomkins, O.; Heinemann, U.; Friedman, A. Lasting blood-brain barrier disruption induces epileptic focus in the rat somatosensory cortex. J. Neurosci. 2004, 24, 7829–7836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vezzani, A.; Aronica, E.; Mazarati, A.; Pittman, Q.J. Epilepsy and brain inflammation. Exp. Neurol. 2013, 244, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchi, N.; Granata, T.; Ghosh, C.; Janigro, D. Blood-brain barrier dysfunction and epilepsy: Pathophysiologic role and therapeutic approaches. Epilepsia 2012, 53, 1877–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Löscher, W.; Potschka, H. Drug resistance in brain diseases and the role of drug efflux transporters. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2005, 6, 591–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchi, N.; Granata, T.; Freri, E.; Ciusani, E.; Ragona, F.; Puvenna, V.; Teng, Q.; Alexopolous, A.; Janigro, D. Efficacy of anti-inflammatory therapy in a model of acute seizures and in a population of pediatric drug resistant epileptics. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e18200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prisma 2009 Checklist. Available online: www.prisma-statement.org (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Vega-García, A.; Orozco-Suárez, S.; Villa, A.; Rocha, L.; Feria-Romero, I.; Alonso Vanegas, M.A.; Guevara-Guzmán, R. Cortical expression of IL1- β, Bcl-2, Caspase-3 and 9, SEMA-3a, NT-3 and P-glycoprotein as biological markers of intrinsic severity in drug-resistant temporal lobe epilepsy. Brain Res. 2021, 1758, 147303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorigados Pedre, L.; Morales Chacón, L.M.; Pavón Fuentes, N.; Robinson Agramonte, M.L.A.; Serrano Sánchez, T.; Cruz-Xenes, R.M.; Díaz Hung, M.L.; Estupiñán Díaz, B.; Báez Martín, M.M.; Orozco-Suárez, S. Follow-Up of Peripheral IL-1 β and IL-6 and Relation with Apoptotic Death in Drug-Resistant Temporal Lobe Epilepsy Patients Submitted to Surgery. Behav. Sci. 2018, 8, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saengow, V.E.; Chiangjong, W.; Khongkhatithum, C.; Changtong, C.; Chokchaichamnankit, D.; Weeraphan, C.; Kaewboonruang, P.; Thampratankul, L.; Manuyakorn, W.; Hongeng, S.; et al. Proteomic analysis reveals plasma haptoglobin, interferon-γ, and interleukin-1β as potential biomarkers of pediatric refractory epilepsy. Brain Dev. 2021, 43, 431–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litovchenko, A.V.; Zabrodskaya, Y.M.; Sitovskaya, D.A.; Khuzhakhmetova, L.K.; Nezdorovina, V.G.; Bazhanova, E.D. Markers of Neuroinflammation and Apoptosis in the Temporal Lobe of Patients with Drug Resistant Epilepsy. J. Evol. Biochem. Physiol. 2021, 57, 1040–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabrodskaya, Y.; Paramonova, N.; Litovchenko, A.; Bazhanova, E.; Gerasimov, A.; Sitovskaya, D.; Nezdorovina, V.; Kravtsova, S.; Malyshev, S.; Skiteva, E.; et al. Neuroinflammatory Dysfunction of the Blood–Brain Barrier and Basement Membrane Dysplasia Play a Role in the Development of Drug-Resistant Epilepsy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamanaka, G.; Takamatsu, T.; Morichi, S.; Yamazaki, T.; Mizoguchi, I.; Ohno, K.; Watanabe, Y.; Ishida, Y.; Oana, S.; Suzuki, S.; et al. Interleukin-1 β in peripheral monocytes is associated with seizure frequency in pediatric drug-resistant epilepsy. J. Neuroimmunol. 2021, 352, 577475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panina, Y.S.; Timechko, E.E.; Usoltseva, A.A.; Yakovleva, K.D.; Kantimirova, E.A.; Dmitrenko, D.V. Biomarkers of Drug Resistance in Temporal Lobe Epilepsy in Adults. Metabolites 2023, 13, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Česká, K.; Papež, J.; Ošlejšková, H.; Slabý, O.; Radová, L.; Loja, T.; Libá, Z.; Svěráková, A.; Brázdil, M.; Aulická, Š. CCL2/MCP-1, interleukin-8, and fractalkine/CXC3CL1: Potential biomarkers of epileptogenesis and pharmacoresistance in childhood epilepsy. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 2023, 46, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gakharia, T.; Bakhtadze, S.; Lim, M.; Khachapuridze, N.; Kapanadze, N. Alterations of Plasma Pro-Inflammatory Cytokine Levels in Children with Refractory Epilepsies. Children 2022, 9, 1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rumià, J.; Marmol, F.; Sanchez, J.; Giménez-Crouseilles, J.; Carreño, M.; Bargalló, N.; Boget, T.; Pintor, L.; Setoain, X.; Donaire, A.; et al. Oxidative stress markers in the neocortex of drug-resistant epilepsy patients submitted to epilepsy surgery. Epilepsy Res. 2013, 107, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorigados Pedre, L.; Gallardo, J.M.; Morales Chacón, L.M.; Vega García, A.; Flores-Mendoza, M.; Neri-Gómez, T.; Estupiñán Díaz, B.; Cruz-Xenes, R.M.; Pavón Fuentes, N.; Orozco-Suárez, S. Oxidative Stress in Patients with Drug Resistant Partial Complex Seizure. Behav. Sci. 2018, 8, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Z.; Tang, J.; Peng, S.; Cai, X.; Rong, X.; Yang, L. Serum concentration of high-mobility group box 1, Toll-like receptor 4 as biomarker in epileptic patients. Epilepsy Res. 2023, 192, 107138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, M.; Song, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, J.; Fang, P. Circulating high mobility group box-1 and toll-like receptor 4 expressions increase the risk and severity of epilepsy. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2019, 52, e7374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledo, A.; Orozco-Suárez, S.; Rosetti, M.; Maldonado, L.; Bautista, S.I.; Flores, X.; Arellano, A.; Moreno, S.; Alonso, M.; Martínez-Juárez, I.E.; et al. Temporal lobe epilepsy: Evaluation of central and systemic immune-inflammatory features associated with drug resistance. Seizure 2021, 91, 447–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, B.; Chaves, J.; Carvalho, C.; Rangel, R.; Santos, A.; Bettencourt, A.; Lopes, J.; Ramalheira, J.; Silva, B.M.; da Silva, A.M.; et al. Brain expression of inflammatory mediators in Mesial Temporal Lobe Epilepsy patients. J. Neuroimmunol. 2017, 313, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, K.I.; Elisevich, K.V. Brain region and epilepsy-associated differences in inflammatory mediator levels in medically refractory mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. J. Neuroinflamm. 2016, 13, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pernhorst, K.; Herms, S.; Hoffmann, P.; Cichon, S.; Schulz, H.; Sander, T.; Schoch, S.; Becker, A.J.; Grote, A. TLR4, ATF-3 and IL8 inflammation mediator expression correlates with seizure frequency in human epileptic brain tissue. Seizure Eur. J. Epilepsy 2013, 22, 675–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonmez, F.M.; Serin, H.M.; Alver, A.; Aliyazicioglu, R.; Cansu, A.; Can, G.; Zaman, D. Blood levels of cytokines in children with idiopathic partial and generalized epilepsy. Seizure Eur. J. Epilepsy 2013, 22, 517–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rijkers, K.; Majoie, H.J.; Hoogland, G.; Kenis, G.; De Baets, M.; Vles, J.S. The role of interleukin-1 in seizures and epilepsy: A critical review. Exp. Neurol. 2009, 216, 258–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazhanova, E.D.; Kozlov, A.A.; Litovchenko, A.V. Mechanisms of Drug Resistance in the Pathogenesis of Epilepsy: Role of Neuroinflammation. A Literature Review. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Arisi, G.M.; Mims, K.; Hollingsworth, G.; O’Neil, K.; Shapiro, L.A. Neuroinflammatory mechanisms of post- traumatic epilepsy. J. Neuroinflammation 2020, 17, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Leung, W.L.; Zamani, A.; O’Brien, T.J.; Casillas Espinosa, P.M.; Semple, B.D. Neuroinflammation in Post-Traumatic Epilepsy: Pathophysiology and Tractable Therapeutic Targets. Brain Sci. 2019, 9, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tishler, D.M.; Weinberg, K.I.; Hinton, D.R.; Barbaro, N.; Annett, G.M.; Raffel, C. MDRl Gene Expression in Brain of Patients with Medically Intractable Epilepsy. Epilepsia 1995, 36, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vliet EAVan Aronica, E.; Gorter, J.A. Blood–brain barrier dysfunction, seizures and epilepsy. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2015, 38, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerri, C.; Genovesi, S.; Allegra, M.; Pistillo, F.; Püntener, U.; Guglielmotti, A.; Perry, V.H.; Bozzi, Y.; Caleo, M. The Chemokine CCL2 Mediates the Seizure-enhancing Effects of Systemic Inflammation. J. Neurosci. 2016, 36, 3777–3788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, S.-I.; Kim, J.-E.; Ryu, H.J.; Seo, C.H.; Lee, B.C.; Choi, I.-G.; Kim, D.-S.; Kang, T.-C. The roles of fractalkine/CX3CR1 system in neuronal death following pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus. J. Neuroimmunol. 2011, 234, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zeng, K.; Han, Y.; Wang, L.; Chen, D.; Xi, Z.; Wang, H.; Wang, X.; Chen, G.-J. Altered Expression of CX3CL1 in Patients with Epilepsy and in a Rat Model. Am. J. Pathol. 2012, 180, 1950–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hung, Y.W.; Lai, M.T.; Tseng, Y.J.; Chou, C.C.; Lin, Y.Y. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 affects migration of hippocampal neural progenitors following status epilepticus in rats. J. Neuroinflamm. 2013, 10, 777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardenas-Rodriguez, N.; Huerta-Gertrudis, B.; Rivera-Espinosa, L.; Montesinos-Correa, H.; Bandala, C.; Carmona-Aparicio, L.; Coballase-Urrutia, E. Role of Oxidative Stress in Refractory Epilepsy: Evidence in Patients and Experimental Models. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 1455–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, M.; Li, Q.Y. Age Dependence of Seizure-Induced Oxidative Stress. Neuroscience 2003, 118, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.; Patel, M. Seizure-induced changes in mitochondrial redox status. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2006, 40, 316–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, R.M. Investigation of oxidative stress involvement in hippocampus in epilepsy model induced by pilocarpine. Neurosci. Lett. 2009, 462, 225–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldbaum, S.; Patel, M. Mitochondrial Oxidative Stress in Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 2010, 88, 23–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, M.; Li, Q.Y.; Chang, L.Y.; Crapo, J.; Liang, L.P. Activation of NADPH oxidase and extracellular superoxide production in seizure-induced hippocampal damage. J. Neurochem. 2005, 92, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumià, J.; Marmol, F.; Sanchez, J.; Carreño, M.; Bargalló, N.; Boget, T.; Pintor, L.; Setoain, X.; Bailles, E.; Donaire, A.; et al. Eicosanoid levels in the neocortex of drug-resistant epileptic patients submitted to epilepsy surgery. Epilepsy Res. 2012, 99, 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazarati, A.; Maroso, M.; Iori, V.; Vezzani, A.; Carli, M. High-mobility group box-1 impairs memory in mice through both toll-like receptor 4 and Receptor for Advanced Glycation End Products. Exp. Neurol. 2011, 232, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Y.; Lei, Z.; Zhang, H.; Xu, Z.; Cui, Q.; Xu, Z.C. Toll-like receptor 4 is associated with seizures following ischemia with hyperglycemia. Brain Res. 2014, 1590, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, S.; Drislane, F.W. Treatment of Refractory and Super-refractory Status Epilepticus. Neurotherapeutics 2018, 15, 697–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barker-Haliski, M.L.; Löscher, W.; White, H.S.; Galanopoulou, A.S. Neuroinflammation in epileptogenesis: Insights and translational perspectives from new models of epilepsy. Epilepsia 2017, 58 (Suppl. 3), 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balosso, S.; Liu, J.; Bianchi, M.E.; Vezzani, A. Disulfide-Containing High Mobility Group Box-1 Promotes N-Methyl-d-Aspartate Receptor Function and Excitotoxicity by Activating Toll-Like Receptor 4-Dependent Signaling in Hippocampal Neurons. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2014, 21, 1726–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroso, M.; Balosso, S.; Ravizza, T.; Liu, J.; Aronica, E.; Iyer, A.M.; Rossetti, C.; Molteni, M.; Casalgrandi, M.; Manfredi, A.A.; et al. Toll-like receptor 4 and high-mobility group box-1 are involved in ictogenesis and can be targeted to reduce seizures. Nat. Med. 2010, 16, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiavegato, A.; Zurolo, E.; Losi, G.; Aronica, E.; Carmignoto, G. The inflammatory molecules IL-1β and HMGB1 can rapidly enhance focal seizure generation in a brain slice model of temporal lobe epilepsy. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Liu, K.; Wake, H.; Teshigawara, K.; Yoshino, T.; Takahashi, H.; Mori, S.; Nishibori, M. Therapeutic effects of anti- HMGB1 monoclonal antibody on pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus in mice. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, G.; Gao, Q.; Zhai, F.; Chen, Y.; Li, T. Upregulation of HMGB1, toll-like receptor and RAGE in human Rasmussen’s encephalitis. Epilepsy Res. 2016, 123, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Li, J.; Shang, Y.; Zhao, L.; Wang, M.; Shi, J.; Li, S. HMGB1-TLR4 Axis Plays a Regulatory Role in the Pathogenesis of Mesial Temporal Lobe Epilepsy in Immature Rat Model and Children via the p38MAPK Signaling Pathway. Neurochem. Res. 2017, 42, 1179–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, H.S.; Koh, S.H. Neuroinflammation in neurodegenerative disorders: The roles of microglia and astrocytes. Transl. Neurodegener. 2020, 9, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ginhoux, F.; Greter, M.; Leboeuf, M.; Nandi, S.; See, P.; Gokhan, S.; Mehler, M.F.; Conway, S.J.; Ng, L.G.; Stanley, E.R.; et al. Fate mapping analysis reveals that adult microglia derive from primitive macrophages. Science 2010, 330, 841–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claycomb, K.I.; Johnson, K.M.; Winokur, P.N.; Sacino, A.V.; Crocker, S.J. Astrocyte regulation of CNS inflammation and remyelination. Brain Sci. 2013, 3, 1109–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study Design | Sample Size (DRE/Control) | Biomarkers Studied | Analytical Method | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case–control (n = 8) and Cohort (n = 1) | 331 (153/178) combined | IL-1, IL-1β, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-7, IL-10, IL-17A, and TNF-α | Varies (plasma and brain tissue analysis) | Most studies showed significantly higher levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines in DRE patients. Exceptions include one study with lower IL-1β and another with lower TNF-α, possibly due to participant age and disease duration, respectively. |

| Study Design | Sample Size (DRE/Control) | Biomarkers Studied | Analytical Method | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cross-sectional (n = 1), Case–control (n = 1), and Cohort (n = 1) | 87 (42/45) combined | CCL2/MCP-1, CX3CL1, CCL11, CCL4, and CCL5 | Varies (plasma and brain tissue analysis) | Most studies found elevated chemokine levels in DRE patients compared to controls, except for one study where CCL2 and CCL4 levels were not significantly different. |

| Study Design | Sample Size (DRE/Control) | Biomarkers Studied | Analytical Method | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retrospective Case–control (n = 1) and Prospective Case-control (n = 1) | 129 (38/91) combined | Reactive oxygen species (O2−), antioxidant enzymes (SOD, catalase, GPx, GR), and biomolecular damage markers (lipid peroxidation, DNA oxidation) | Varies (brain tissue and blood sample analysis) | Both studies showed a significant elevation in some oxidative stress markers. One study found elevated O2−, catalase, and DNA oxidation in brain tissue, while the other found elevated lipid peroxidation and SOD activity in blood samples. |

| Study Design | Sample Size (DRE/Control) | Biomarkers Studied | Analytical Method | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HMGB1: Cohort (n = 1) & Case–control (n = 1) | 277 (70/207) combined | High Mobility Group Box 1 (HMGB1) | Serum sample analysis | Both studies reported significantly higher serum HMGB1 levels in DRE patients, suggesting a strong correlation with drug resistance. |

| TLR-4: Cohort (n = 1) & Case–control (n = 2) | 277 (70/207) combined | Toll-Like Receptor 4 (TLR-4) | Varies (serum and brain tissue analysis) | All three studies found significantly higher levels and expression of TLR-4 in DRE patients, suggesting a role in the pathogenesis of drug resistance. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abdullahi, A.M.; Sarmast, S.T.; Abdulrazak, U.I. The Role of Microglial Activation in the Pathogenesis of Drug-Resistant Epilepsy: A Systematic Review of Clinical Studies. BioChem 2025, 5, 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/biochem5040043

Abdullahi AM, Sarmast ST, Abdulrazak UI. The Role of Microglial Activation in the Pathogenesis of Drug-Resistant Epilepsy: A Systematic Review of Clinical Studies. BioChem. 2025; 5(4):43. https://doi.org/10.3390/biochem5040043

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbdullahi, Abba Musa, Shah Taha Sarmast, and Usama Ishaq Abdulrazak. 2025. "The Role of Microglial Activation in the Pathogenesis of Drug-Resistant Epilepsy: A Systematic Review of Clinical Studies" BioChem 5, no. 4: 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/biochem5040043

APA StyleAbdullahi, A. M., Sarmast, S. T., & Abdulrazak, U. I. (2025). The Role of Microglial Activation in the Pathogenesis of Drug-Resistant Epilepsy: A Systematic Review of Clinical Studies. BioChem, 5(4), 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/biochem5040043