Promoting Sustainable Tourism in the Areia Branca Beach of Timor-Leste: Innovations in Governance and Digital Marketing

Abstract

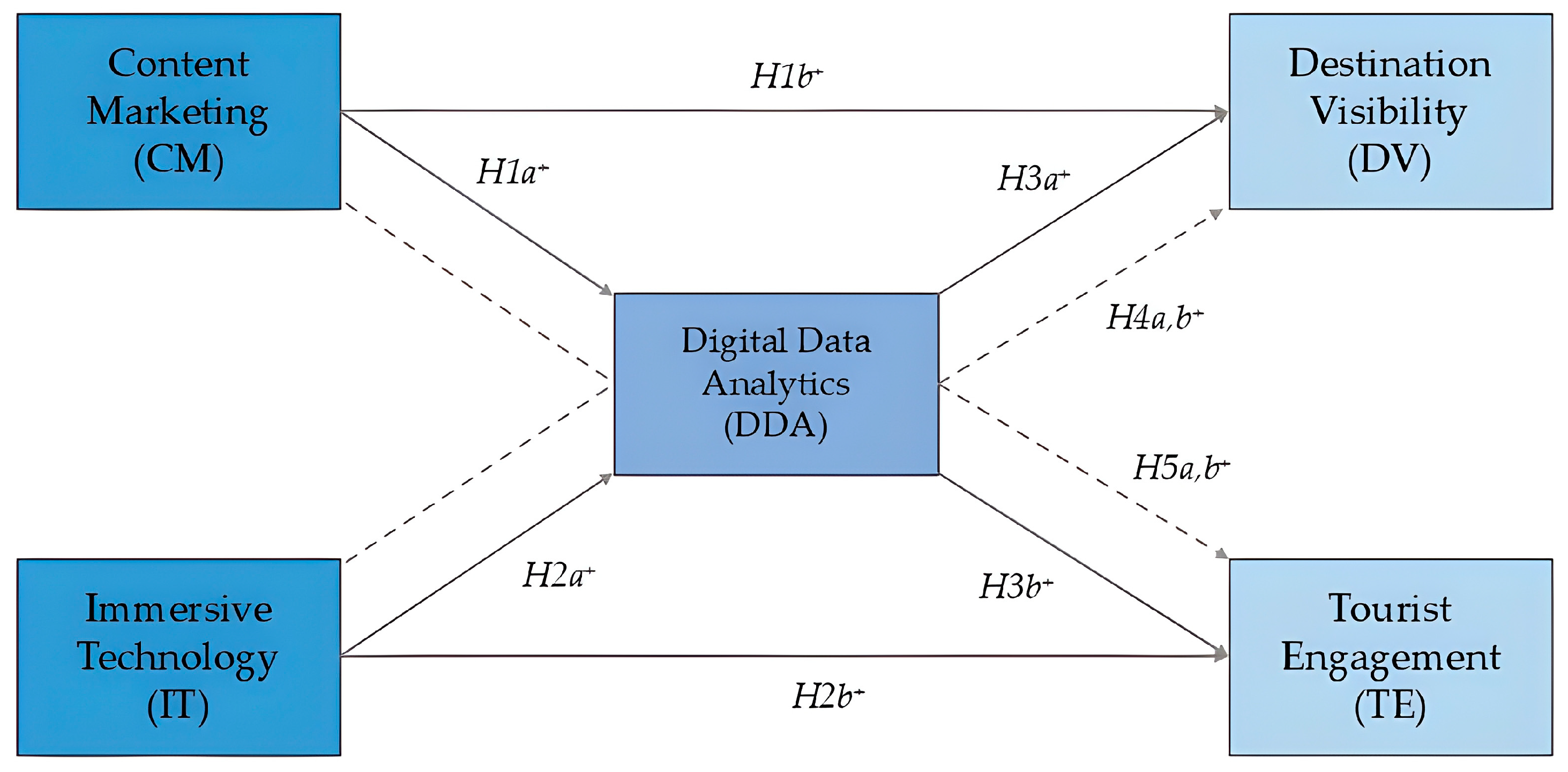

1. Introduction

- -

- RQ1: Does content marketing influence digital data analytics and destination visibility?

- -

- RQ2: Does immersive technology influence digital data analytics and tourist engagement?

- -

- RQ3: Does digital data analytics influence destination visibility and tourist engagement?

- -

- RQ4: Do content marketing and immersive technology through digital data analytics influence destination visibility?

- -

- RQ5: Do content marketing and immersive technology, facilitated by digital data analytics, influence tourist engagement?

2. Literature Review and Conceptual Model Development

2.1. Theoretical Basis

2.2. Empirical Basis

2.2.1. Content Marketing

2.2.2. Immersive Technology

2.2.3. Digital Data Analytics

2.2.4. Destination Visibility

2.2.5. Tourist Engagement

2.3. Conceptual Framework

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Approach and Instruments

3.2. Variable Specifications

3.3. Sample

3.4. Data Analysis

- -

- If the t-value is less than the critical value from the t-table at a p-value ≥ 0.01 or 0.05, then the H0 fails to be rejected at confidence levels of 99% and 95%, respectively. Consequently, there is insufficient statistical evidence to support the Ha.

- -

- If the calculated t-value is greater than or equal to the critical t-value from the table, with a p-value < 0.01 or 0.05, then the H0 is rejected at the 99% or 95% confidence level, respectively, indicating very strong statistical evidence in favour of the Ha.

4. Results

4.1. Respondents’ Profiles

4.2. Descriptive Statistics

4.3. Questionnaire Data Testing

4.4. Modelling Feasibility Testing

4.5. Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 2D | Two-dimensional |

| 3D | Three-dimensional |

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| AR | Augmented reality |

| CA | Cronbach’s alpha |

| CM | Content marketing |

| CMB | Common method bias |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus disease 2019 |

| DDA | Digital data analytics |

| DV | Destination visibility |

| EFA | Exploratory factor analysis |

| FPC | Finite population correction |

| GDP | Gross domestic product |

| KMO | Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin |

| MRA | Moderated regression analysis |

| IT | Immersive technology |

| ITC | Item-total correlation |

| PTOM | Porcelain Temple Online Museum |

| P2P | Peer-to-peer |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| SEM | Structural equation modeling |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| SRS | Simple random sampling |

| STI | Sustainable Tourism Index |

| TE | Tourist engagement |

| ToF | Top-of-feed |

| UCA | User-centric analytics |

| UGC | User-generated content |

| US$ | United States Dollar |

| VIF | Variance inflation factor |

| VR | Virtual reality |

| WoM | Word-of-mouth |

| XR | Extended reality |

References

- Aggag, A., & Kortam, W. (2025). Using augmented reality to improve tourism marketing effectiveness. Sustainability, 17(13), 5747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, R., Baharuddin, S. A., & Azmi, N. A. (2024). The role of digital marketing as a resilience factor in cultural heritage tourism: A conceptual paper. International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Science, 8(6), 1408–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhaddar, M., & Kummitha, H. R. (2025). Digitalization and sustainable branding in tourism destinations from a systematic review perspective. Discover Sustainability, 6(1), 1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhazzaa, K., & Yan, W. (2025). Immersive technologies in education: Exploring user experience and engagement in building energy simulations through AR and VR. Computers & Education: X Reality, 6, 100097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral Vong, E. W. N., Purwatiningsih, A. S. E., da Canossa Vong, M., & Aulia, T. F. (2024). Sustainable tourism development impact at small island tourism destination at Timor-Leste; A systematical literature review. JMET: Journal of Management Entrepreneurship and Tourism, 2(2), 195–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amir, S., Astuti, W., Chandrarin, G., & Narmaditya, B. S. (2025). The role of memorable travel experiences in bridging tourist enthusiasm, interaction, and behavioral intentions in ecotourism destinations. Discover Sustainability, 6(1), 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, B. D. L. (2024). Strategy of the ministry of pariwista Timor-Leste in the development of community based pariwista. EKOMA: Jurnal Ekonomi, Manajemen, Akuntansi, 3(4), 1897–1904. [Google Scholar]

- Asia Foundation. (2018). Survey of travelers to Timor-Leste in 2017. Available online: https://asiafoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/2017-Survey-of-Travelers-to-Timor-Leste_EN.pdf?utm (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Azahari, M. A., Razali, M. A. S., & Md Ali, A. (2025). Applying design thinking for tourism innovation: Developing a web-based platform for destination visibility. Journal of Contemporary Tourism and Hospitality Research, 1(1), 53–73. [Google Scholar]

- Bajrami, R., Gashi, A., Bajraktari, K., & Namligjiu, E. (2025). The impact of big data analytics on digital marketing decision-making: A comprehensive analysis. Innovative Marketing, 21(3), 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banco Central de Timor-Leste. (2025). Economic bulletin: A quarterly publication of the central bank of Timor-Leste. Available online: https://www.bancocentral.tl/uploads/documentos/documento_1756953310_3578.pdf (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Binh Nguyen, P. M., Pham, X. L., & To Truong, G. N. (2023). A bibliometric analysis of research on tourism content marketing: Background knowledge and thematic evolution. Heliyon, 9(2), e13487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahyosusatyo, N. N. G., & Hudiono, R. K. (2024). Pengaruh pemasaran digital dalam meningkatkan angka kunjungan melalui citra destinasi Jungleland pasca pandemi COVID 19 [The influence of digital marketing in increasing visitor numbers through the image of Jungleland as a destination after the COVID-19 pandemic]. Jurnal Manajemen Perhotelan dan Pariwisata, 7(2), 104–112. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, W. C., Lo, M. C., Wan Ibrahim, W. H., Mohamad, A. A., & Kadim bin Suaidi, M. (2022). The effect of hard infrastructure on perceived destination competitiveness: The moderating impact of mobile technology. Tourism Management Perspectives, 43, 100998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H. H., & Chiang, C. C. (2022). Is virtual reality technology an effective tool for tourism destination marketing? A flow perspective. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology, 13(3), 427–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheiran, J. F. P., Bandeira, D. R., & Pimenta, M. S. (2025). Measuring the key components of theuser experience in immersive virtualreality environments. Frontiers in Virtual Reality, 6, 1585614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. F., & Ding, C. G. (2025). An improvement in the detection of common method biases. Quality & Quantity. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L., Wu, X., Liu, Y., Hu, Z., Chen, X., & Zhang, Z. (2025). Integrating TAM-ISSM-SOR framework to explore how virtual tourism experience influences tourists’ travel intention. Scientific Reports, 15(1), 38826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christou, E., Giannopoulos, A., & Simeli, I. (2025). The evolution of digital tourism marketing: From hashtags to AI-immersive journeys in the metaverse era. Sustainability, 17(13), 6016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dağ, K., Çavuşoğlu, S., & Durmaz, Y. (2024). The effect of immersive experience, user engagement and perceived authenticity on place satisfaction in the context of augmented reality. Library Hi Tech, 42(4), 1331–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, T. D., & Nguyen, M. T. (2023). Systematic review and research agenda for the tourism and hospitality sector: Co-creation of customer value in the digital age. Future Business Journal, 9(1), 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, J. (2012). Choosing the type of probability sampling. In Choosing the type of probability sampling (pp. 125–174). SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, J., Marques Júnior, S., & Mendes-Filho, L. (2025). The impact of digital content marketing on travel intentions to tourist destinations: A proposed model based on perceived value and loyalty. BAR—Brazilian Administration Review, 22(2), e240188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Development Asia. (2024). Developing Timor-Leste’s blue economy. Available online: https://www.development.asia/insight/developing-timor-lestes-blue-economy (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Dewi, N. K. C., Trisyani, N. P. N., Yuliani, N. M. D., Pramita, N. K. D., & Jayamahe, N. P. Y. P. (2025). Sustainable tourism: Concept and implementation for sustainable tourism development. Journal Management and Hospitality, 2(2), 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahimah, M., & Yuliani, S. F. (2023). Membangun identitas desa wisata melalui content marketing: Strategi untuk meningkatkan kunjungan wisatawan. Jurnal Ilmiah Manajemen Dan Bisnis, 8(1), 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X., Jiang, X., & Deng, N. (2022). Immersive technology: A meta-analysis of augmented/virtual reality applications and their impact on tourism experience. Tourism Management, 91, 104534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fransisco, T. A. (2024). The impact of virtual reality (VR) technology on enhancing customer engagement in the online travel industry. CEBONG Journal, 3(3), 122–130. [Google Scholar]

- Goncalves, A., Chantra, T., & Chinudomsub, P. (2024). Community empowerment for community-based tourism development in the border region of Timor-Leste: A case study of Atabae sub-district. Journal of Social Science for Local Development Rajabhat Maha Sarakham University, 8(4), 310–321. [Google Scholar]

- Hafiya, A. I., & Trihantoro, J. (2024). Peran visitor engagement dan destination image terhadap revisit intention yang dimediasi oleh memorable tourism experiences [The role of visitor engagement and destination image on revisit intention mediated by memorable tourism experiences]. Journal of Economics and Business UBS, 13(3), 811–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardiyanto, D., Wijaya, M., & Satyawan, A. (2025). The role of marketing communications in influencing the promotion and visibility of tourist destinations: A systematic literature review. Journal of Sustainable Tourism and Entrepreneurship, 6(2), 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inkasari, Y., Haifa, H., & Maspufah, H. (2025). Pengaruh harga, online customer review dan content marketing terhadap keputusan pembelian melalui minat beli pada marketplace TikTok shop di Jember [The influence of price, online customer reviews and content marketing on purchasing decisions through purchase interest on the TikTok shop marketplace in Jember]. JMBI: Jurnal Manajemen Bisnis Dan Informatika, 5(2), 186–205. [Google Scholar]

- Iswanto, D., Irsyad, Z., & Istiqlal, I. (2024). Mobile-based marketing innovation as an effort to increase tourist interaction and engagement in the tourism industry. SCIENTIA: Journal of Multi-Disciplinary Science, 3(2), 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, L. A. (2025). Community-based tourism: A catalyst for achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals one and eight. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(1), 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jebson, R., & Ikelberg, J. (2014). Timor-Leste tourism research and development. Business opportunities and support services (BOSS) project, ILO, Irish aid, New Zealand MFAT. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/sites/default/files/wcmsp5/groups/public/%40asia/%40ro-bangkok/%40ilo-jakarta/documents/publication/wcms_419652.pdf (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- Kheiri, J. (2023). Tourists’ engagement in cultural attractions: An exploratory study of psychological and behavioural engagement in indigenous tourism. International Journal of Anthropology and Ethnology, 7(1), 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieanwatana, K., & Vongvit, R. (2024). Virtual reality in tourism: The impact of virtual experiences and destination image on the travel intention. Results in Engineering, 24, 103650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, K., Sedlmair, M., & Schreiber, F. (2022). Immersive analytics: An overview. IT—Information Technology, 64(4–5), 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krisnatalia, H., Hendarajaya, H., Aryasa, A. B., & Wicaksono, D. A. (2025). Dampak keterlibatan dalam virtual tourism terhadap niat menggunakan virtual tourism dan motivation for real world travel di kalangan generasi Z di Indonesia [The impact of involvement in virtual tourism on the intention to use virtual tourism and motivation for real-world travel among Generation Z in Indonesia]. Jurnal Manajemen STIE Muhammadiyah Palopo, 11(1), 94–101. [Google Scholar]

- Kurolov, M., Sobirjonov, S., & Jumayev, A. (2025, December 30–31). Impact of digital marketing in tourism industry: A data driven marketing analytics approach. The 8th International Conference on Management, Accounting, Economics and Social Sciences (pp. 859–863), Dubai, United Arab Emirates. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, X., & Furkan, L. M. (2025). The influence of social media in tourism marketing strategy: Side by side research in China and Indonesia. Asian Journal of Applied Business and Management, 4(1), 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandagi, D. W., Indrajit, I., & Wulyatiningsih, T. (2024). Navigating digital horizons: A systematic review of social media’s role in destination branding. Journal of Enterprise and Development, 6(2), 373–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Market Development Facility. (2024). Timor-Leste annual report 2024. Available online: https://marketdevelopmentfacility.org/2024-annual-report/wp-content/uploads/MDF-Annual-Report-2024-Timor-Leste.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Nazare, A.-K., Moldoveanu, A., & Moldoveanu, F. (2024). Virtual journeys, real engagement: Analyzing user experience on a virtual travel social platform. Information, 15(7), 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, S. H. (2025). Leveraging virtual reality experiences to shape tourists’ behavioral intentions: The mediating roles of enjoyment and immersion. Journal of Zoological and Botanical Gardens, 6(2), 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nor Mohd Anuar, A., Mohd Nazaruddin, N. A. I., Omar, S. S., & Zulkurnain, M. Z. (2025). An analysis of smart tourism technologies (STTs) at visitor attractions: Investigating the influence of information, accessibility, interactivity, personalization, and security on tourist satisfaction. International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Science, 9(9), 9862–9875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurhaeni, T., Azka, R., Arasid, N. S., Sunengsih, M., & Evans, R. (2025). Big data analytics and online promotional strategies to boost digital business sales. ADI Bisnis Digital Interdisiplin Jurnal, 6(1), 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oka, I. M. D., & Subadra, I. N. (2024). Digital marketing for sustainable tourism village in Bali: A mixed methods study. Journal of Infrastructure, Policy and Development, 8(7), 3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozili, P. K. (2023). The acceptable R-square in empirical modelling for social science research. In Advances in knowledge acquisition, transfer, and management (pp. 134–143). IGI Global. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacific Tourism Organisation. (2025). Timor-Leste CAS report 2024–2025. Available online: https://southpacificislands.travel/home/research/pacific-tourism-data-initiative/ptdi-reports-timor-leste/timor-leste-cas-report-2024-2025/ (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Pahabol, A., Purnama, D., Rahmadina, E., & Vania, F. (2024). Analisis strategi pemasaran digital suatu destinasi wisata [An analysis of digital marketing strategies of a tourism destination]. Kultura: Jurnal Ilmu Hukum, Sosial, Dan Humaniora, 2(11), 901–910. [Google Scholar]

- Parab, A. (2025). Beyond the screen: Immersive analytics with augmented reality/virtual reality. International Journal of Computing and Engineering, 7(5), 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Permana, B. R. S., Kenedi, K., & Huda, M. (2024). Utilization of virtual reality as a sustainable tourism promotion strategy based on information technology in Banten Province. JINAV: Journal of Information and Visualization, 5(2), 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polas, M. R. H. (2025). Common method bias in social and behavioral research: Strategic solutions for quantitative research in the doctoral research. Journal of Comprehensive Business Administration Research. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramono, R., & Juliana, J. (2025). Beyond tourism: Community empowerment and resilience in rural Indonesia. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(4), 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratisto, E. H., Thompson, N., & Potdar, V. (2022). Immersive technologies for tourism: A systematic review. Information Technology & Tourism, 24(2), 181–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prihadi, D. J., Shalahuddin, M. R., Novianti, E., Junirahma, N. S., Pamungkas, W., Dhahiyat, A. P., Annida, S. B., & Lahbar, G. M. (2024). The ‘Tri Hita Karana’ ecotourism approach for sustainable marine resource management and tourism in Bali. International Journal of Marine Engineering Innovation and Research, 9(4), 858–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punzo, G., Trunfio, M., Castellano, R., & Buonocore, M. (2022). A multi-modelling approach for assessing sustainable tourism. Social Indicators Research, 163(3), 1399–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rancati, E., & Gordini, N. (2014). Content marketing metrics: Theoretical aspects and empirical evidence. European Scientific Journal, 10(34), 92–104. [Google Scholar]

- Rasul, T., Santini, F. de O., Lim, W. M., Buhalis, D., Ramkissoon, H., Ladeira, W. J., Pinto, D. C., & Azhar, M. (2024). Tourist engagement: Toward an integrated framework using meta-analysis. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 31(4), 845–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rideng, I. W., Mahendrawati, N. L. M., Setyawati, N. K. A., Marta, I. D. G. M., Reiro, L., & Manuel, J. (2024). Institutional strengthening in supporting ecotourism development in the Branca Area tourist area, Dili-Timor Leste. Asian Journal of Community Services, 3(11), 1039–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rifqi, H. M. (2025). Virtual reality in tourism research: A thematic literature review. SBS Journal of Applied Business Research, 13(2), 59–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Real, J. L., Uribe-Toril, J., & Gázquez-Abad, J. C. (2020). Destination branding: Opportunities and new challenges. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 17, 100453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saputra, I. P. D. A. (2023). Pemanfaatan digital marketing dalam mempromosikan destinasi pariwisata [The utilisation of digital marketing in promoting tourism destinations]. AL-MIKRAJ: Jurnal Studi Islam Dan Humaniora, 4(1), 345–353. [Google Scholar]

- Saputri, M. K., & Fahimah, M. (2025). Efektivitas content marketing dalam membentuk brand awareness dan minat berkunjung ulang: Studi kasus desa wisata [The effectiveness of content marketing in shaping brand awareness and repeat visits: A case study of a tourist village]. Sadar Wisata: Jurnal Pariwisata, 8(1), 12–20. [Google Scholar]

- Sari, N., Mahrinasari, M. S., & Erlina, E. (2023). Digital content marketing influences people to visit tourist destinations. International Journal of Advances in Social Sciences and Humanities, 2(3), 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathyanarayana, S., & Mohanasundaram, T. (2025). Moderation analysis in business research: Concepts, methodologies, applications and emerging trends. Asian Journal of Economics, Business and Accounting, 25(3), 357–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satrya, I. D. G., Kaihatu, T. S., Budidharmanto, L. P., Karya, D. F., & Rusadi, N. W. P. (2023). The role of ecotourism in preserving environmental awareness, cultural and natural attractiveness for promoting local communities in Bali, Indonesia. Journal of Eastern European and Central Asian Research, 10(7), 1063–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharafuddin, M. A., Madhavan, M., & Wangtueai, S. (2024). Assessing the effectiveness of digital marketing in enhancing tourist experiences and satisfaction: A study of Thailand’s tourism services. Administrative Sciences, 14(11), 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singgalen, Y. A. (2024). Understanding digital engagement through sentiment analysis of tourism destination through travel vlog reviews. KLIK: Kajian Ilmiah Informatika dan Komputer, 4(6), 2992–3004. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, S., Lee, S., & Tsai, K. (2025). The impact of smart tourism technologies on engagement, experiences, and place attachment: A focused study with gamification as the moderator. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 36, 100997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. (2025). Travel & tourism—Timor-Leste [Market data & analysis]. Available online: https://www.statista.com/outlook/mmo/travel-tourism/timor-leste (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- Stecuła, K., & Naramski, M. (2025). Virtual reality as a green tourism alternative: Social acceptance and perception. Sustainability, 17(17), 7722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D., Zhou, Y., Ali, Q., & Khan, M. T. I. (2025). The role of digitalization, infrastructure, and economic stability in tourism growth: A pathway towards smart tourism destinations. Natural Resources Forum, 49(2), 1308–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sustacha, I., Baños-Pino, J. F., & Del Valle, E. (2023). The role of technology in enhancing the tourism experience in smart destinations: A meta-analysis. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 30, 100817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Untari, D. T. (2024). Optimalisasi fungsi pemasaran digital dalam memasarkan natural base tourism di Indonesia; Sebuah kajian literatur [Optimising digital marketing functions in marketing natural base tourism in Indonesia; A literature review]. Jurnal Komunikasi dan Ilmu Sosial, 2(3), 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uong, L. N. T. (2025). The ability to maintain the attractiveness of destinations: Exploring the role of digital marketing. Advances in Consumer Research, 2(4), 4979–4988. [Google Scholar]

- ur Rehman, S., Khan, S. N., Antohi, V. M., Bashir, S., Fareed, M., Fortea, C., & Cristian, N. P. (2024). Open innovation big data analytics and its influence on sustainable tourism development: A multi-dimensional assessment of economic, policy, and behavioral factors. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 10(2), 100254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.-L., & Azizurrohman, M. (2024). From virtual to reality: The influence of digital engagement and memorable experiences on tourist revisit intentions. ASEAN Marketing Journal, 6(2), 169–187. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. (2025). Timor-Leste economic report. Land of opportunities: How modern land administration can unlock Timor-Leste’s economic transformation. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099091925052531343/pdf/P506964-3040f528-8756-4559-970a-368c00c9eb52.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Xaiver, J., Dewi, L. K. C., & da Conçeicão Soares, A. (2020). Marketing strategy analysis for developing a small-scale business in tourism, in Island Atauro tourism object, Dili Timor Leste. International Journal of Multicultural and Multireligious Understanding, 7(8), 549–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ximenes, R., Dewi, N. D. U., & Widnyani, I. A. P. S. (2024). Strategic tourism development by the municipal government of Baucau, Timor-Leste. Jurnal Studi Pemerintahan Dan Akuntabilitas, 4(1), 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalçınkaya, N., Arca, D., & Keskin Citiroglu, H. (2025). Producing alternative tourism routes using network analysis to promote Seferihisar cittaslow concept. Information Technology & Tourism, 27(3), 705–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, D., Marzuki, A. B., Yang, J., Zhou, J., & Tao, S. (2025). Bibliometric analysis of smart tourism destination: Knowledge structure and research evolution (2013–2025). Tourism and Hospitality, 6(4), 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yannacopoulou, A., & Kallinikos, K. (2025). Measuring destination image using AI and big data: Kastoria’s image on TripAdvisor. Societies, 15(1), 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yawised, K., & Apasrawirote, D. (2025). The synergy of immersive experiences in tourism marketing: Unveiling insightful components in the ‘Metaverse’. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 37, 101019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Papp-Váry, Á., & Szabó, Z. (2025). Digital engagement and visitor satisfaction at world heritage sites: A study on interaction, authenticity, and recommendations in coastal China. Administrative Sciences, 15(3), 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.-H., & Huang, H.-C. (2025). Enhancing sustainable tourism through virtual reality: The role of collectable experiences in well-being and meaning in life. Sustainability, 17(13), 5809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D. (2024). Tourism destination marketing strategy driven by big data. Journal of Computational Methods in Sciences and Engineering, 24(4-5), 2593–2609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M., & Yu, H. (2022). Exploring how tourist engagement affects destination loyalty: The intermediary role of value and satisfaction. Sustainability, 14(3), 1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Definition | Indicators | Statement Items | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content marketing (CM) | A marketing strategy centered on creating and distributing engaging, consistent, relevant, and valuable content to attract and retain the target audience, thereby fostering positive interactions with the image of Areia Branca Beach. | (1) Content relevance (2) Accuracy and clarity of information (3) Added value (4) Ease of finding content (5) Content consistency | CM1: The published content helps me understand the available tours. CM2: The information displayed in the tourism content is accurate. CM3: The content provides useful information for me. CM4: I can easily find information about these tours on the website and social media platforms. CM5: The message and style of the content remain consistent over time. | (Inkasari et al., 2025; Rancati & Gordini, 2014) |

| Immersive technology (IT) | Incorporating technologies such as AR, VR, and mixed reality (MR) to create interactive and immersive digital experiences that allow tourists to feel fully immersed in a virtual environment or seamlessly blended with Areia Branca Beach in real life. | (1) Sense of presence (2) Usability (3) Immersive experience (4) Aesthetic experience (5) Emotional response | IT1: I feel completely immersed when using immersive technology. IT2: The controls in immersive applications are intuitive and highly responsive. IT3: I quickly become absorbed in the experience provided by immersive technology. IT4: The sound and audio effects in immersive technology enhance the realism of the experience. IT5: The immersive experience excites me. | (Alhazzaa & Yan, 2025; Cheiran et al., 2025; Dağ et al., 2024) |

| Digital data analytics (DDA) | A series of processes involving the collection, extraction, tracking, and interpretation of digital data to gain insights that support understanding tourist behavior at Areia Branca Beach, improve the effectiveness of digital campaigns, and inform strategic decision-making. | (1) Data integration and quality (2) Analytical capabilities (3) Utilisation of analytical outputs (4) Operational performance efficiency | DDA1: The data used for analytics is of high quality, stable, complete, and ideal. DDA2: Coastal authorities possess the technical expertise required to perform multifaceted digital data analyses. DDA3: The results of digital data analysis are used to develop digital marketing strategies. DDA4: Digital analytics helps reduce marketing operational costs. | (Bajrami et al., 2025; Nurhaeni et al., 2025) |

| Destination visibility (DV) | The extent to which a tourist destination is visible and easily recognizable to potential tourists—both online and offline—through various digital information and promotional channels, as well as relevant and effective marketing communications, influences the likelihood of Areia Branca Beach being chosen by tourists. | (1) Online visibility (2) Digital promotion (3) Easily accessible information (4) Function and usefulness of UGC (5) Exposure in tourism media and global platforms | DV1: Areia Branca Beach is easy to find through internet searches. DV2: The social media accounts of Areia Branca Beach frequently receive interactions and comments from potential tourists. DV3: Information about ticket prices, schedules, and destination facilities is easily accessible. DV4: Positive reviews from tourists increase the interest of other potential visitors. DV5: The destination has global visibility, not merely local or national. | (Azahari et al., 2025; Hardiyanto et al., 2025; Liang & Furkan, 2025) |

| Tourist engagement (TE) | The cognitive, emotional, and active participation levels of tourists during their experience at Areia Branca Beach—including contribution and feelings of active involvement throughout their visit. | (1) Enthusiasm and interaction (2) Behavioural engagement (3) Cognitive engagement (4) Emotional engagement | TE1: The tourist activities here energized me, especially through direct interaction with the offerings at Areia Branca Beach. TE2: I took many videos and photos to document my experience. TE3: I tried to understand the meaning and context of the places I visited. TE4: I feel that my experience here has provided me with meaningful memories, enjoyment, and happiness. | (Amir et al., 2025; Hafiya & Trihantoro, 2024; Kheiri, 2023) |

| Selection Criteria | Sample |

|---|---|

| Respondents by FPC size | 373 |

| Respondents who completed the questionnaires | 364 |

| Respondents who completed but did not return the questionnaires | 6 |

| Respondents who were unwilling to complete the questionnaires | 2 |

| Total number of complete and valid respondents | 364 |

| Status | Characteristics | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 195 | 53.6 |

| Female | 169 | 46.4 | |

| Age range (years) | 18–30 | 74 | 20.3 |

| 31–43 | 155 | 42.6 | |

| 44–56 | 118 | 32.4 | |

| ≥56 | 17 | 4.7 | |

| Country of origin (arrival) | Australia | 143 | 39.3 |

| Indonesia | 86 | 23.6 | |

| Portugal | 38 | 10.4 | |

| New Zealand | 50 | 13.7 | |

| China | 35 | 9.6 | |

| Others | 12 | 3.3 | |

| Occupation | Government employee | 70 | 19.2 |

| Company employee | 106 | 29.1 | |

| Researcher | 45 | 12.4 | |

| Entrepreneur | 62 | 17 | |

| Banker | 52 | 14.3 | |

| Not working | 29 | 8 | |

| Average monthly salary (US$) | <1500 | 43 | 11.8 |

| 1500–2500 | 67 | 18.4 | |

| 2501–3500 | 81 | 22.3 | |

| 3501–4500 | 129 | 35.4 | |

| 4501–5500 | 50 | 13.7 | |

| ≥5500 | 37 | 10.2 | |

| Frequency of visits (times) | 2 | 216 | 59.3 |

| 3–4 | 113 | 31 | |

| ≥4 | 35 | 9.6 |

| Variables | Mean | Maximum | Minimum | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content marketing (CM) | 3.88 | 5 | 2 | 0.59 |

| Immersive technology (IT) | 3.82 | 5 | 2.1 | 0.54 |

| Digital data analytics (DDA) | 3.65 | 4.9 | 1.8 | 0.63 |

| Destination visibility (DV) | 3.7 | 5 | 2 | 0.57 |

| Tourist engagement (TE) | 3.78 | 4.8 | 1.75 | 0.61 |

| Variables | Indicators | CMB | Reliability (α) | Validity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Eigenvalues | % of Variance | Cumulative (%) | ITC (r) | KMO | Barlett’s Test (p) | |||

| Content marketing (CM) | CM1 | 7.5 | 32.6 | 32.6 | 0.64 | |||

| CM2 | 2.85 | 12.4 | 45 | 0.67 | ||||

| CM3 | 2.1 | 9.1 | 54.1 | 0.823 | 0.65 | 0.78 | 0.000 | |

| CM4 | 1.75 | 7.6 | 61.7 | 0.63 | ||||

| CM5 | 1.5 | 6.5 | 68.2 | 0.76 | ||||

| Immersive technology (IT) | IT1 | 1.25 | 5.4 | 73.6 | 0.73 | |||

| IT2 | 1.1 | 4.8 | 78.4 | 0.75 | ||||

| IT3 | 0.95 | 4.1 | 82.5 | 0.91 | 0.77 | 0.83 | 0.001 | |

| IT4 | 0.85 | 3.7 | 86.2 | 0.74 | ||||

| IT5 | 0.8 | 3.5 | 89.7 | 0.66 | ||||

| Digital data analytics (DDA) | DDA1 | 0.7 | 3 | 92.7 | 0.61 | |||

| DDA2 | 0.6 | 2.6 | 95.3 | 0.854 | 0.64 | 0.81 | 0.000 | |

| DD3 | 0.5 | 2.2 | 97.5 | 0.62 | ||||

| DDA4 | 0.35 | 1.5 | 99 | 0.67 | ||||

| Destination visibility (DV) | DV1 | 0.2 | 0.9 | 99.9 | 0.71 | |||

| DV2 | 0.05 | 0.2 | 100 | 0.811 | 0.66 | 0.77 | 0.000 | |

| DV3 | 0.03 | 0.1 | 100 | 0.69 | ||||

| DV4 | 0.01 | 0 | 100 | 0.65 | ||||

| DV5 | 0.01 | 0 | 100 | 0.73 | ||||

| Tourist engagement (TE) | TE1 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0.7 | |||

| TE2 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0.872 | 0.75 | 0.79 | 0.000 | |

| TE3 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0.68 | ||||

| TE4 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0.72 | ||||

| Models | Simultaneous Test | Determination Test | Multicollinearity Test (VIF) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F-Statistics | p | R2 | Adjusted R2 | ||

| Model 1 | 34.912 | 0.016 * | 0.712 | 0.701 | 2.243 |

| Model 2 | 29.864 | 0.019 * | 0.669 | 0.548 | 3.215 |

| Model 3 | 38.527 | 0.000 ** | 0.848 | 0.837 | 1.287 |

| Linkages (Hypotheses) | Standardized Coefficient (β) | Standard Error (SE) | t-Statistics | Sig. (p) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CM → DDA (H1a) | 0.352 | 0.082 | 4.29 | 0.000 ** |

| CM → DV (H1b) | 0.178 | 0.09 | 1.98 | 0.049 * |

| IT → DDA (H2a) | 0.295 | 0.085 | 3.47 | 0.006 ** |

| IT → TE (H2b) | 0.121 | 0.088 | 1.37 | 0.171 |

| DDA → DV (H3a) | 0.421 | 0.078 | 5.39 | 0.000 ** |

| DDA → TE (H3b) | 0.198 | 0.081 | 2.44 | 0.014 * |

| CM x DDA → DV (H4a) | 0.152 | 0.075 | 2.03 | 0.033 * |

| IT x DDA → DV (H4b) | 0.089 | 0.072 | 1.24 | 0.217 |

| CM x DDA → TE (H5a) | 0.114 | 0.073 | 1.56 | 0.12 |

| IT x DDA → TE (H5b) | 0.168 | 0.07 | 2.4 | 0.018 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mardika, I.M.; Wijaya, I.K.K.A.; Putra, I.B.U.; Ribeiro, L.; Surgawati, I.; Darma, D.C. Promoting Sustainable Tourism in the Areia Branca Beach of Timor-Leste: Innovations in Governance and Digital Marketing. Tour. Hosp. 2026, 7, 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp7020028

Mardika IM, Wijaya IKKA, Putra IBU, Ribeiro L, Surgawati I, Darma DC. Promoting Sustainable Tourism in the Areia Branca Beach of Timor-Leste: Innovations in Governance and Digital Marketing. Tourism and Hospitality. 2026; 7(2):28. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp7020028

Chicago/Turabian StyleMardika, I Made, I Ketut Kasta Arya Wijaya, Ida Bagus Udayana Putra, Leonito Ribeiro, Iis Surgawati, and Dio Caisar Darma. 2026. "Promoting Sustainable Tourism in the Areia Branca Beach of Timor-Leste: Innovations in Governance and Digital Marketing" Tourism and Hospitality 7, no. 2: 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp7020028

APA StyleMardika, I. M., Wijaya, I. K. K. A., Putra, I. B. U., Ribeiro, L., Surgawati, I., & Darma, D. C. (2026). Promoting Sustainable Tourism in the Areia Branca Beach of Timor-Leste: Innovations in Governance and Digital Marketing. Tourism and Hospitality, 7(2), 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp7020028