1. Introduction

Technology within the hotel industry has evolved significantly, with a particular focus on AI and automation (

Wu et al., 2023). The sector was traditionally based on hospitality service delivery standards that focus almost entirely on human touchpoints throughout the guest journey. The need for efficiency, personalisation, and meeting the demands of happy customers led some incremental hotels to introduce more advanced technologies (

Zhang et al., 2023). In times of ever-growing change and where it is becoming easier to be disruptive in a marketplace already in turmoil, largely due to unpredictable consumer expectations that seem to know no variation for continuity, this shift has secured a competitive advantage, at least for now (

Ngari & Mwangi, 2023;

Štilić et al., 2023). The implementation of AI-shared technology has brought a radical transformation across many operational vertices of the hospitality industry, including customer service and revenue management. Uses of artificial intelligence (AI) in hotels and motels can include automation at check-in, personalised recommendations, chatbots, and dynamic pricing. Clearly understanding how guests access and, to a reasonable degree, use these AI systems would be valuable for creating strategies that deepen loyalty to our brand. The guest experience has been a big focus for hotels, and they have increasingly relied on artificial intelligence (AI) to deliver it. This automatic approach enables hotels to analyse vast amounts of data surrounding trends in the guest journey (refer to

Figure 1). Artificial intelligence (AI) is shaping the way travellers book hotels and how hoteliers classify rooms, open doors, and manage customer service calls. In the space of hotel and motel accommodations, we see this trend carry across multiple use cases for AI applications, from automating check-in to providing bespoke recommendations customised for each guest, to deploying chatbots for customer service queries and implementing dynamic demand response pricing. As these technologies continue to proliferate, it is essential for us to learn as much as we can about what guests see, feel, and do in relation to AI systems, and how they interact with them. Such insights are crucial for creating successful content strategies that not only build brand loyalty but also improve overall customer satisfaction.

This study aims to fill the gap and respond to

Wang et al.’s (

2025) call to explore the multifaceted relationships between trust in AI, performance expectancy, willingness to accept AI, and affective brand loyalty and purchase intention in the context of hotel accommodations in New Zealand. Additionally,

Yassin et al. (

2022, p. 51), argued “there needs to be more research on Artificial Intelligence in the hotel sector”. To address this gap, the current study aims to examine the effect of trust in AI, cultural factors, and performance expectancy on the willingness to accept AI, with purchase intention as a mediating factor that leads to brand loyalty through hotel accommodations in New Zealand. Recent studies suggest that the construction of cognitive trust is crucial in AI and robotic applications used by consumers, such as artificial intelligence and robots employed in tourism and hospitality (

Tussyadiah et al., 2020). In addition, with the development of cloud computing and other digital technologies, hotels can store, process, and analyse more data to enhance their operational efficiency and competitiveness (

Štilić et al., 2023). It is no longer a trend; it is an evolution that is necessary due to the changes in guest preferences and expectations for personalisation and efficiency in delivering services. It is also important because the emotional and cognitive responses of guests to artificial intelligence technologies have a significant impact on their experience and satisfaction.

In addition, research has shown that sensory cues provided by Internet of Things (IoT) devices can influence guests’ emotions and behavioural intentions, which suggests adding a multi-sensory ambience in luxury hotels (

Pelet et al., 2021). Also, the role of hotel staff is still significant because their behaviour towards the guest can help or detract from the overall experience and end with brand loyalty and purchase intentions (

Višković et al., 2023) in the hospitality industry, which is an integral part of customer experience management (CEM) in terms of different hotel units, which must work together and have a culture to provide customers with satisfactory service (

Rahimian et al., 2021). As the hotel space continues to evolve, it will become increasingly challenging for AI technologies to avoid disturbing or failing to meet the expectations of their guests. Overall, guests are increasingly open to AI tools, although their preference often remains for human interactions, which are considered by guests to be more sincere and authentic (

Marković & Gjurašić, 2020). This raises an interesting consideration for hotel operators in reconciling the extent to which AI can be integrated with the requirement for human interaction. Acceptance of AI technologies: In addition, the evaluation of the adoption intention or acceptance is determined by the value perception, trust, and service experience (to form attitudes and behaviours toward using hotel brands) of guests, since these factors are simultaneously influenced by positive and negative stimulations from services, for instance (

Bravo et al., 2019;

Lo & Yeung, 2019).

2. Theoretical Background

This study’s conceptual framework is rooted within the Technological Acceptance Model, TAM (

Davis, 1989), the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology, UTAUT (

Venkatesh et al., 2003), and the

Morgan and Hunt (

1994) Trust and Commitment theory (

Morgan & Hunt, 1994). TAM, as introduced by

Davis (

1989), demonstrates that the consumers’ attitude in adopting new technology is influenced by two streams of thought: the perceived usefulness (PU) and the perceived ease of use (PEOU). In the former, if the technology is perceived as useful and capable of improving their work or productivity, users are more likely to adopt it. For instance, a user might feel that the use of AI such as a chatbot in the hotel industry could shorten the room booking procedure and answer queries more quickly than a human, thus heightening its perceived usefulness. Similarly, UTAUT (

Venkatesh et al., 2003) denotes the extent to which a user believes that using a system would be free of effort. Users are more likely to adopt technology if they find it user-friendly, as complex systems may deter usage due to the possibility of making mistakes and the longer learning curve.

The Commitment–Trust theory, as posited by

Morgan and Hunt (

1994), expresses the importance of the relationship between commitment and trust in establishing, as well as maintaining, continuous ties between organisations and their customers. Commitment–Trust theory builds a baseline for relationship marketing, where the organisation values the continuing long-term business from a customer much more than a single transaction. The authors theorise that trust is the main attribute for a long-term commitment.

2.1. Purchase Intention and Brand Loyalty

Purchase intention is a decisive factor to determine the purchase behaviour of consumers (

Zhong et al., 2020, p. 2). It is a personal motivation that ultimately envisages an accurate behaviour (

Fishbeinn & Ajzen, 1975). Nevertheless, a consumer purchase decision is a complex process. It can reflect the likelihood or probability that a consumer will make a purchase based on certain situations and conditions such attitudes, perceptions, and evaluations of the brand, product attributes, or marketing stimuli (

Fishbeinn & Ajzen, 1975). In the tourism and hospitality literature, purchase intention has been affected by factors such as, among others, services quality, location, hotel website usability, and location (

Pee et al., 2018;

Su et al., 2016).

On the other spectrum, in defining brand loyalty, we borrow

Oliver’s (

1999, p. 34) definition as “a deeply held commitment to rebuy or re-patronise a preferred product/service consistently in the future, thereby causing repetitively same-brand or same-brand-set purchasing despite situational influences and marketing efforts having the potential to cause switching behaviour”.

Oliver’s (

1999) definition of brand loyalty is rooted in two sub-domains: behavioural and attitudinal (

Chaudhuri & Holbrook, 2001). Behavioural loyalty enhances repurchase intention, while attitudinal loyalty emphasises dispositional commitment. Brand attitudinal loyalty is the emotional attachment and positive feeling that guests develop toward a hotel brand based on their positive experiences (

Chaudhuri & Holbrook, 2001). It reflects long-term loyalty and a preference for the brand. Consumers with strong affective loyalty are more likely to develop a long-term commitment, resist competitors’ offers, and advocate for the brand (

Chaudhuri & Holbrook, 2001). Unlike cognitive or behavioural loyalty, which are based on rational evaluation or repeated purchase behaviour, affective loyalty reflects the emotional bond that makes consumers genuinely care about and feel connected to the brand.

Brand loyalty has a substantial effect on the financial performance of hotels (

H. Kim et al., 2003). Loyalty towards hotel brands is nurtured by positive guest experiences, quality service, satisfaction, brand image, and certainty of repeat purchase (

Dewi et al., 2021;

Wisker et al., 2020). In full-service hotels, customer experience and brand attitude play an important role in promoting social and functional experiences that drive customers to stay loyal (

Guan et al., 2021). Affective commitment influences hotel guests to exhibit loyalty and focuses on the bonds that are developed with brands in terms of emotions (

Mattila, 2006). With the emergence of virtual hotel operations, brand loyalty has become increasingly important in order for hotels to maintain a relationship with their customers online through engagements (

Situmorang & Aruan, 2021). Brand loyalty development in full-service hotels has been revealed as a key effect of customer brand engagement and customer brand affect (

Situmorang & Aruan, 2021;

Guan et al., 2021).

Liu et al. (

2022) also emphasise that customer engagement is significantly related to service quality and brand image, which enhances purchase and repurchase intentions, resulting in brand loyalty. Additionally,

Wisker et al. (

2020) have observed how repurchase intention led to brand loyalty in the hotel industry. Summarising the discussion, therefore, it is fair to posit the following:

H1. Purchase intention positively affects brand loyalty.

2.2. Trust in Artificial Intelligence (AI), Purchase Intention, and Brand Loyalty

Trust is defined as “a willingness to rely on an exchange partner in whom one has confidence and has the enduring desire to maintain a valued relationship” (

Moorman et al., 1993, p. 82).

Moorman et al.’s (

1993) definition of trust is, however, mainly associated with people and partners, and not technology. Nevertheless, trust is crucial in business to contribute to a lack of functional conflict, uncertainty, and cooperation, leading to commitment (

Morgan & Hunt, 1994). In conceptualising trust in AI, we borrow

Choung et al.’s (

2022) concept, which argues that trust in AI has two dimensions: (1) human-like trust in AI and (2) functionality trust in AI. Human-like trust is related to the social, cultural, and ethical values of the algorithm that undergird the design of the AI, whereas functionality trust in AI is related to the competency and expertise in the technological features. Another useful concept of trust in technology is from

Mcknight et al. (

2011). They argue that trust in technology involves confidence in the system’s reliability, integrity, and benevolence.

Humans develop trust in AI based particularly on two system attributes: predictability and reliability (

Dorton & Harper, 2022).

Dorton and Harper (

2022) argue that predictability is related to how consistently the system behaves and how well the user can anticipate its actions, while reliability is related to how the system performs and works as intended. In strengthening our argument to demonstrate the relationship between trust in AI, purchase intentions, and brand loyalty, we borrow the theory of Trust–Commitment from

Morgan and Hunt (

1994).

Morgan and Hunt (

1994) posit that trust and commitment lead to cooperative behaviour, reduce uncertainty, and promote long-term engagement. Hence, it is not surprising that, for decades, the tourism marketing literature has documented the positive relationship between trust, purchase intentions, and brand loyalty (

Elziny & Mohamed, 2022;

Wisker et al., 2020). In the literature on hotel accommodations, it has been documented that trust in AI can influence guests’ overall satisfaction, usage intention, and loyalty to the brand (

Choung et al., 2022;

Du et al., 2025;

Zhong et al., 2020). Translating this concept to the current study, it is fair to predict that trust in AI will enhance the use of AI, resulting in purchase intentions and long-term commitment to the brand. Hence, the study hypothesises the following:

H2a. Trust in AI positively impacts purchase intentions.

H2b. Trust in AI impacts affective brand loyalty, and this relationship is mediated by purchase intentions.

2.3. AI Performance Expectancy, Purchase Intention, and Brand Loyalty

Performance expectancy is the extent to which a person believes using the system will help him or her perform better in their work and/or life (

Upadhyay et al., 2021). It is a predictor of whether guests perceive AI as beneficial in enhancing their stay. The construct is an essential part of different technology acceptance models, such as the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT), where it serves as a major predictor of behavioural intention to adopt new technologies (

Venkatesh et al., 2003). The concept of performance expectancy has also been said to enhance the intended use of AI (

Houtsman, 2020). Accordingly,

Houtsman (

2020) argued that perceived AI performance is related to the transparency of how AI works, its effectiveness and efficiency, and the level of users’ satisfaction. AI performance is related to the belief that AI will improve the guests’ experience by delivering efficient, personalised, and high-quality services. AI performance expectancy is also related to believing that technology would help them to complete the task quickly (

Upadhyay et al., 2021). The degree to which people believe that using a particular technology will encourage them in achieving job benefits is one of the performance expectancies (

Venkatesh et al., 2003). In hospitality, performance expectancy regarding AI systems can be associated with the benefits that are perceived to occur: speedy check-ins or personalisable services and robust issue resolution. A higher performance expectancy has been found to have a direct and positive impact on acceptance and satisfaction (

J. Kim et al., 2022;

Islam & Zhou, 2023). The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) in the hospitality sector is vital for enhancing operational efficiency, improving customer experiences, influencing purchase intention (PI), and ultimately leading to improved financial performance (

Gatera, 2024;

Ivanov et al., 2019). Hence, it is fair to hypothesise the following:

H3a. The AI’s perceived performance expectancy positively impacts purchase intentions.

H3b. The AI’s perceived performance expectancy impacts affective brand loyalty, and this relationship is mediated by purchase intentions.

2.4. Willingness to Accept AI, Purchase Intention, and Brand Loyalty

We borrow the concept of technology readiness to explain the notion of willingness to accept services provided by AI. The concept of technology readiness centres around the basic needs of individuals who use technology to meet certain requirements (

Parasuraman, 2000;

Pham et al., 2020). When a person believes that a technology can assist them with a certain requirement, it leads to their willingness to accept it. Therefore, the willingness to accept AI signifies the degree to which subjects are prone to accept AI technologies in different scenarios because they believe it will assist them in that given scenario (

Pham et al., 2020). The psychological and behavioural drivers of a consumer’s willingness to adopt AI-related content go beyond the context of functional utility, resonating more with the dimensions of perceived value (

Xu et al., 2024). If services from AI are seen to deliver higher levels of perceived value, the propensity to become more favourable to a purchase decision significantly increases (

Beyari & Hashem, 2025;

Huang & Rust, 2020). This observation is also supported by behavioural theories such as Stimulus–Organism–Response, S-O-R (

Mehrabian & Russell, 1974). S-O-R stipulates that external cues and social responses elicit mental and emotion reactions, resulting in a behavioural response. For instance, if a hotel guest believes that the services recommended by AI are best aligned with their requirements, this will result in a formulated positive attitude, which increases their purchase intention.

Several empirical studies in hospitality and hotel industries have also observed the willingness among hotel guests and customers to use AI services, reflecting an acceptance of technological advancement, resulting in an enhanced purchase intention and brand loyalty (

Bilgihan et al., 2025;

Chotisarn & Phuthong, 2025;

Gajić et al., 2024). Building on the previous literature,

Bilgihan et al. (

2025) observed that customer loyalty in the hospitality industry in the era of new technology has often been enhanced by the willingness to use AI, where an AI agent underscores their critically effective strategies to enhance customer retention.

Islam and Zhou (

2023) found that consumers accept and are willing to use AI in the hotel industry due to AI’s perceived performance expectancy, perceived interaction enjoyment, cuteness, and social influences. Summarising the discussion, we posit the following:

H4a. Willingness to accept AI positively impacts purchase intentions.

H4b. Willingness to accept AI impacts brand loyalty, and this relationship is mediated by purchase intentions.

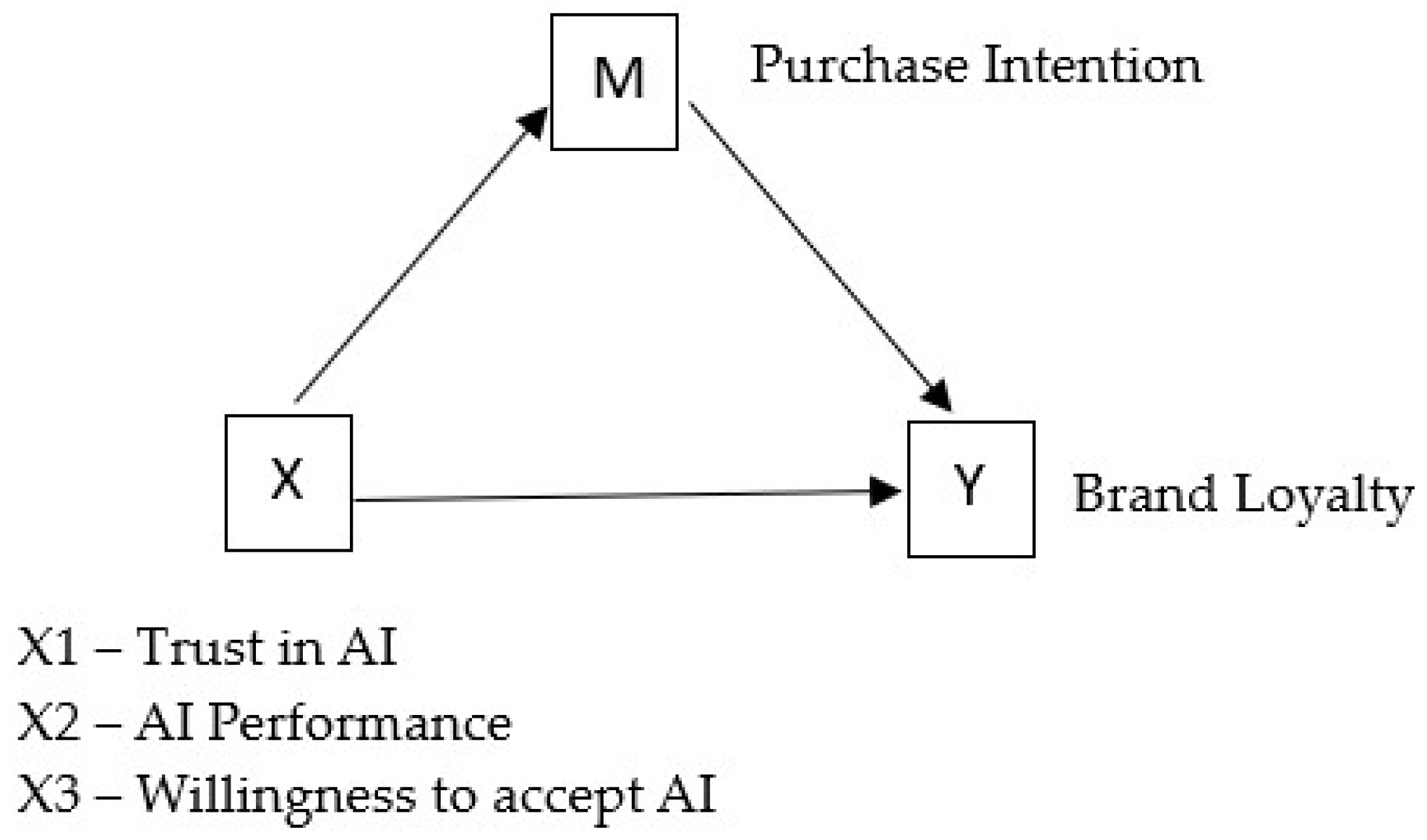

Figure 2, outlined in the framework model, shows that trust in AI, AI performance, and willingness to accept AI impact purchase intentions and brand affective loyalty. The model indicates that purchase intentions mediate the relationships among trust, performance, willingness to accept AI, and brand loyalty.

3. Methods

The aim of the study is to examine the effect of trust in AI, perceived AI performance, and willingness to accept AI on brand loyalty. The study further posits that purchase intention has a mediating role between the understudied independent and dependent variables. In an attempt to examine these hypotheses, the study has collected quantitative cross-sectional data using an online survey. We used an online survey for its cost-effective, quicker data collection, wider reach, and, to some degree, because it provides automated descriptive data analysis (

Creswell & Creswell, 2017).

This study adopts a positivist research philosophy and a deductive, theory-driven approach. Drawing on the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT), and Commitment–Trust theory, we developed testable hypotheses about the relationships between trust in AI, performance expectancy, willingness to accept AI, purchase intention, and affective brand loyalty. Consistent with this paradigm, we employed a quantitative, cross-sectional survey design, collecting standardised data from hotel guests in New Zealand at a single point in time. This design is appropriate for examining directional relationships between latent constructs and testing mediation effects.

3.1. Sampling Frame and Sample Size

The study surveys tourists and travellers in New Zealand who have had experience staying in hotel accommodations. The research focuses on individuals who have already stayed in a hotel, as it needed to inquire into the participants’ decision-making process for booking accommodations. To comply with the ethics, participants were asked to confirm that they were at least 18 years old and had stayed in a hotel before proceeding with the survey. No identifying information was requested in the questionnaire, and responses were stored in aggregate form, supporting participant confidentiality.

The study was granted ethical approval from the College Ethics Committee on 13th August, 2024, so it complies with ethical standards and guidelines and respects participants’ rights and well-being.

Data were collected within the window of eight days between 15 August 2024 and 29 September 2024. Because there is no complete sampling frame of recent hotel guests in New Zealand, the study used a non-probability, self-selection sampling strategy. Participants were recruited through voluntary responses to the online invitation circulated via social media and email. This approach is common in hospitality research, but it limits the extent to which the findings can be generalised to the wider population of hotel guests. Data were collected primarily through social media platforms. The survey link was shared on various social media platforms, including Facebook, LinkedIn, and Instagram, as well as through public/community channels and by email to potential participants.

In determining the sample size, we followed

Cohen’s (

1992) suggestion; to set an acceptable sample size, a study has to consider four factors: (1) the study’s objectives, (2) the population size, (3) the margin of sampling error, and (4) the confidence level. For this study, an alpha (α) level was set at 0.05–0.07 to minimise Type 1 error risk (

Cohen, 1992).

Cohen (

1992) also advises targeting a statistical power level (1-β) of 0.8 or higher, on the grounds that it provides an 80% chance of detecting an effect. Ultimately, the study received a total of 185 responses, of which 2 were excluded due to missing data, leaving a total of 183 responses to be analysed. A sample size of 183 participants provides a power of almost 80% to detect an effect size (r) = 0.02, with a Type I margin error rate α = 4.64% (Calculator.net).

3.2. Measures and Reliability Test

A total of 21 structured questionnaires, including 3 demographic questions on gender, age, and income level, were constructed. We used established scales to measure the understudied variables. Trust in AI and AI performance expectancy were measured using a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. The instruments were adapted from scales that have been widely used in tourism and hospitality or service contexts and have demonstrated acceptable validity and reliability in prior studies. For instance, Xu et al., Zhong et al., Bloemer et al., and Gajic et al. report Cronbach’s alpha values above 0.70 and evidence of convergent and discriminant validity for these scales in related settings, which supports their suitability for the present context. The brand loyalty scale was borrowed from

Bloemer et al. (

1999). Finally, purchase intention was measured using a 3-item scale adapted from

Zhong et al. (

2020).

This study examines the scale’s reliability through EFA (Exploratory Factor Analysis). We assess the EFA through its factor loading. According to

Cohen (

1992), no item should have a factor loading less than 0.4, and these factors should preferably be eliminated from the analysis. A factor loading higher than 0.4 can be considered significant, and values above 0.5 can be considered as large (

Hair et al., 2014). The factor loadings for this measure in the present study ranged from 0.7 to 0.9, indicating that convergent validity was met (

Cohen, 1992;

Hair et al., 2014). Then, the study determines its reliability via Cronbach’s alpha. A lower alpha coefficient indicates an inability to measure the target construct adequately. On the other hand, a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient greater than 0.6 indicates an acceptable internal reliability (

Cohen, 1992). Cronbach’s alphas for the study’s measures ranged from 0.70 to 0.88, indicating acceptable internal consistency. The summary of reliability findings is depicted in

Table 1.

3.3. Data Analysis Techniques

Data analysis began with descriptive statistics to summarise and present data clearly (

Mishra et al., 2019), providing a holistic overview (

Kemp et al., 2018). Measures such as percentages, modes, means, and standard deviations were applied to describe data distribution. The standard deviation indicated data variability—smaller values suggested clustering around the mean, while larger ones reflected a wider spread (

Leech et al., 2015). To determine the relationships between variables, a Bivariate Pearson Correlation was conducted. Statistical significance was assessed at the 0.05, 0.01, and 0.001 levels. Effect size, represented by the Pearson coefficient r, indicated the strength and practical significance of relationships (

Gall et al., 2007). Correlations above 0.50 were considered strong, 0.40–0.49 very strong, and those below 0.22 weak and excluded from further analysis (

Cohen, 1992). However, values exceeding 0.70 suggested possible multicollinearity concerns.

Finally, to test the mediation effect, an SPSS Macro PROCESS Model 4 analysis was conducted following

Hayes’s (

2018) recommendation.

Hayes (

2018) maintains that, in the context of a process representing causality, when it comes to an examination of mediation, the researchers should be most interested in the estimation of direct and indirect effects. To estimate these effects, we analyse the components of the indirect path, which are how X affects M and how M also affect Y.

4. Results and Data Analysis

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

The analysis starts with a descriptive look at the data. The 183 valid responses met the usability threshold. The demographic includes attributes for age, sex, and income level. The participants were aged 18 to over 65. The largest age group, 24–34 years, took up 36.61 per cent of the responses, followed by the 45–54 years group, which made up 26.78 per cent. The group aged 65 and older was the least represented, at just under 2.73 per cent. The sample consisted of 89 (48.63%) male and 94 (51.36%) female respondents, which were comparably well-balanced in terms of gender distribution. Overall, the majority (27.32%) made between NZD 40,000 and NZD 60,000 annually, while 12.02% made less than NZD 20 k on a yearly basis. Results for demographics are summarised in

Table 2.

Prior to testing the regression, we test the bivariate correlation to establish the association between the understudied variables.

Table 3 summarises the correlation, mean, and standard deviation results.

4.2. Multicollinearity

Multicollinearity is a statistical phenomenon in which two or more independent variables in a regression model are highly correlated with each other (

Field, 2024;

Leech et al., 2015). When multicollinearity is present, it becomes difficult to isolate the individual effect of each independent variable on the dependent variable, since changes in one predictor are associated with changes in another. This can lead to unstable estimates of regression coefficients and make it challenging to interpret the model. Multicollinearity arises when two or more independent variables are highly correlated, typically indicated by a correlation coefficient (r) greater than 0.8 (

Field, 2024). In reviewing the bivariate correlation results for this study, no variables exhibited multicollinearity.

4.3. Linear Regression Result

Prior to testing the mediation analysis, we conducted a linear test to examine the effect of purchase intentions on brand loyalty. Consistent with our prediction, the effect of purchase intentions on brand loyalty is strong, at (β = 0.628, t = 17.989, p < 0.001), concluding the significance of H1.

4.4. Mediation Effect Result—Test One

In testing the posited hypotheses, the study has adopted Macro SPSS PROCESS Model 4

Hayes (

2018). In testing the mediation effect,

Hayes (

2018) suggested assessing the indirect, direct, and the total effects.

A mediation analysis was conducted to examine the mediating effect of purchase intention on the relationship between trust in AI and brand affective loyalty (H2a and H2b). The direct effect of trust in AI on brand affective loyalty was slightly significant (β = 0.158, t = 2.685,

p = 0.008), and the indirect effect through purchase intention was larger, at (β = 0.4279, BootSE = 0.0754, BootLLCI = 0.2771, BootULCI = 0.5688), supporting H2b.

Table 4 offers an overview of the strengths of the direct, indirect, and total effects.

4.5. Mediation Effect Result—Test Two

The second mediation effect test was conducted to ascertain the relationship between the performance of AI and brand affective loyalty, and if purchase intention mediates the relationship (H3b: Performance expectancy impacts brand loyalty, mediated by purchase intention). The direct effect of the performance of AI on brand affective loyalty was significant (β = 0.168, t = 2.722,

p = 0.007), with a significant indirect effect through purchase intention (β = 0.465, BootSE = 0.082, BootLLCI = 0.291, BootULCI = 0.616), confirming H3b.

Table 5 depicts the results for the direct, indirect, and total effects.

4.6. Mediation Effect Result—Test Three

Finally, test three analysed the impact of the willingness to accept AI on both the purchase intention and brand affective loyalty (H4b: Willingness to accept AI impacts brand loyalty, mediated by purchase intention). The mediating role of purchase intention was confirmed, as the indirect effect of willingness to accept AI on brand affective loyalty was significant (β = 0.5109, BootSE = 0.077, BootLLCI = 0.347, BootULCI = 0.654), supporting only H4b.

Table 6 offers an overview of the strength of the direct, indirect, and total effects, and

Table 7 summarise the experiment.

5. Discussion

Overall, the results provide strong support for the proposed model. H1, H2a, H2b, H3a, and H3b were all significant, indicating that trust in AI and performance expectancy are strongly associated with both purchase intentions and affective brand loyalty, and that purchase intentions transmit much of their effect on loyalty. In contrast, H4a was not supported, as a willingness to accept AI did not have a significant direct effect on purchase intentions, although its indirect effect on brand affective loyalty through purchase intentions (H4b) was significant.

This pattern suggests that simply being open to using AI in hotels is not enough on its own to trigger an immediate intention to book. Rather, a willingness to accept AI seems to operate as a readiness condition that strengthens the way other beliefs about AI (such as trust and perceived performance) translate into purchase intention and, ultimately, affective loyalty. Guests who are willing to accept AI appear more likely to form positive purchase intentions when they also trust AI and perceive it as performing well, which then fosters an emotional bond with the hotel brand. The implications of these results are discussed below.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

The result of this study extends the understanding of the effects of trust in AI, the performance of AI, and the willingness to accept AI on consumer behaviour with regard to the hotel industry. Rooted in the theoretical bases of the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT), and the Trust–Satisfaction theory (

Morgan & Hunt, 1994), this research discusses how these constructs have an impact on consumer attitudes toward AI-driven services in hospitality. The results indicate that trust in AI appears as an important predictor, increasing consumer acceptance by influencing purchase intentions and developing affective brand loyalty. The best example of this comes in the hotel industry: prior research has found that, when guests perceive AI applications to be trustworthy and useful, their intention for interacting with those technologies increases, thus leading them to a higher level of satisfaction and loyalty to the hotel brand (

Morosan, 2025;

Cheng & Guo, 2021).

Furthermore, results from this study show that the benefits of performance associated with AI are substantially favourable to guests’ continued acceptance. The connection between introducing AI to the hotel lobby and making guests comfortable with using tech that allows just about anything you can imagine, from requests for more towels or help turning off lights, is clear; if hotels communicate how these benefits are achieved (personalisation of service delivered has been greatly enhanced by operational efficiency behind the scenes), then their willingness to engage increases. This interaction not only enriches the current user experience but also leads to future brand loyalty. The convergence of perceived performance and the willingness to accept AI corresponds with previous research identifying the significance of brand experience and knowledge in fostering consumer loyalty (

Manthiou et al., 2015).

The theoretical models used in this study, like TAM and UTAUT, appear to be ideal for understanding the acceptance dynamics of technology, which fits well within the hospitality arena. These theories specifically highlight the importance of perceptual mechanisms, such as perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness, in shaping attitudes towards technology (

Cheng & Guo, 2021). Consequently, these perceptions play a crucial role regarding AI in hotels, as they have significant direct implications for consumer trust and, in turn, their overall adoption of AI-based services. The research also highlights the importance of hotel operators building confidence as a top priority for developing a healthy relationship between consumers and AI technologies. For example, transparency in AI operations and details on how the service quality is improved by using such technology can help alleviate consumer apprehensions about the technology (

Morosan, 2025).

Taken together, these findings reinforce the core propositions of technology acceptance theories such as TAM and UTAUT, in that performance expectancy and trust in AI act as key beliefs that shape behavioural intention. By linking these beliefs and intentions to affective brand loyalty, the study also connects technology acceptance perspectives with brand equity and relationship marketing theories. This suggests that AI-enabled services should be viewed not only as process innovations, but also as tools that can strengthen or weaken long-term brand relationships depending on how they are designed and implemented.

In addition, the study’s results are consistent with a broader body of literature on AI and brand loyalty, using consumer behaviour datasets. In the wake of AI technologies infiltrating the hospitality industry, it is imperative to investigate what motivations potentially encourage consumers to adopt such. This research indicates that hotels that effectively embed AI into their services, with a genuine concern for trust and equity, can strengthen guest loyalty and satisfaction. It is consistent with previous work that has shown ethical thoughts to be a relevant factor in consumer perceptions and loyalty (

Fatma & Rahman, 2017). Through data like this, hotel brands can differentiate themselves in an increasingly tech-centric market. This study contributes to the literature by examining trust in AI and its impact on consumer behaviour in the context of hotels within a theoretical framework. Based on the grounded research in extant theoretical foundations, the study has implications for both academics and hotel operators interested in improving customer loyalty with AI-driven innovations. Further research to investigate the changing face of AI in hospitality, particularly with respect to consumer behaviour and brand loyalty after the adoption of technology, should be considered for future studies.

5.2. Managerial/Social Implications

The findings of this study provide some insights for managers and hoteliers about the use of AI in the business. The industry is often sceptical in adopting AI in its day-to-day operation. This study indicates that, not only does the use of AI enhance purchase intentions, but it goes further by improving brand loyalty. This may not come as a surprise, since hotel guests and travellers often prefer efficiency and cost-effectiveness. The use of AI may improve efficiency in the sense that the response to the services may be quicker and can be accessed 24/7. AI has the capability of improving efficiency, automating repetitive tasks, reducing human error, and analysing large amounts of data to provide better insight for data-driven decision-making. With such possibilities, managers and hoteliers could use AI to analyse enormous quantities of data about their guests in order to target customers, create prediction models, and offer better service.

Nevertheless, the study has also observed that a willingness to accept AI was only significant indirectly, implying that there may be some tourists who are still sceptical about receiving services through AI. Despite good AI performance, customers may still prefer human interactions in service settings, reducing the influence of AI performance on purchase decisions. This emphasises that hotel guests still value human services. This finding indicates that AI should complement human roles rather than replace them. Hotel services also often fulfil emotional and experiential needs, which AI performance alone might not address, diminishing its impact on purchase intent. High-performing AI might be perceived as standard or expected, offering no unique incentive to choose the hotel over competitors. The increasing number of scams and fraud which compromise financial information through a purchase action is another major challenge.

Finally, an awareness of the ethical conflicts that surround the use of AI, such as its biassed programming, which may be a result of the original algorithm design, can negatively influence purchase intention. Therefore, the hoteliers and managers need to balance out the services of humans and robots (AI).

5.3. Limitations and Future Studies

The current study suggests several opportunities for future research, acknowledging the limitations of the present data. First, more than 183 responses constitute a reasonable sample size to draw conclusions from, but increasing the overall sample size in future work would increase confidence levels and decrease Type I errors even further. A larger, more diverse sample would also help confirm these findings across variations in demographic or cultural groups, thereby reinforcing the generalisability of our results. In addition, this study uses first-order constructs regarding trust in AI, the performance of AI, and the willingness to accept AI.

Future studies may expand to investigate the multidimensional nature of these variables by using constructs that reflect other facets within each factor. For example, the willingness to accept AI could be measured along other spectrums not previously considered, such as affective and cognitive responses to AI in hospitality (

Wisker et al., 2019). Future studies can improve these construct definitions to gain greater insight into how those variables affect purchase intentions and brand loyalty.

Finally, this study was conducted in New Zealand, a small, high-income country with a strong tourism sector and high levels of digital connectivity. Local norms that value both efficient service and warm interpersonal interaction may influence how guests evaluate AI-enabled hotel services. Combined with the relatively high education levels in our sample, these contextual factors may help to explain the generally positive evaluations of AI and the strong links between AI-related beliefs, purchase intentions, and brand loyalty. As a result, the findings should be generalised with caution to other cultural and market contexts. A possible future pathway could examine the model in countries with different levels of technological maturity, cultural norms around hospitality, and different guest profiles.

6. Conclusions

This study examined how trust in AI, performance expectancy, and willingness to accept AI shape hotel guests’ purchase intentions and affective brand loyalty in New Zealand, drawing on the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT), and Commitment–Trust theory. Using survey data from 183 hotel guests and Hayes’s PROCESS Model 4, we found that a trust in AI and perceived AI performance both have significant direct and indirect effects on affective brand loyalty through purchase intentions. We also found that a willingness to accept AI does not directly influence purchase intentions, but exerts a significant indirect effect on brand loyalty via purchase intentions.

These findings make three main contributions to the literature on AI in hospitality. First, they empirically integrate technology acceptance and relationship marketing perspectives by demonstrating that purchase intentions are a key psychological mechanism linking AI-related beliefs to affective loyalty. Second, by distinguishing trust in AI, performance expectancy, and willingness to accept AI, the study shows that not all AI-related evaluations operate in the same way. Trust and perceived performance behave like classic TAM and UTAUT beliefs that directly shape intentions, whereas the willingness to accept AI functions more as a readiness factor whose influence is expressed through purchase intentions. Third, the results extend emerging work on AI-enabled services in hotels by providing evidence from a New Zealand context, where high digital connectivity and strong service expectations shape how guests balance efficiency gains from AI with human contact.

For practitioners, the results suggest that hotels should prioritise building trustworthy, high-performing AI touchpoints rather than simply deploying more AI. Transparent communication about how AI systems use customer data, clear escalation paths to human staff, and visible safeguards for privacy and security can strengthen guests’ trust in AI. At the same time, AI applications should clearly improve the guest journey, for example, by shortening check-in times, providing relevant recommendations, or resolving issues quickly. When guests perceive AI as both reliable and genuinely helpful, they are more likely to intend to book and to develop affective loyalty to the brand. A willingness to accept AI can also be nurtured through gentle onboarding and choice architecture, such as allowing guests to opt in to AI assistance, providing explainable interfaces and giving guests the option to switch to human support at any time.

The study has some limitations, including its reliance on non-probability sampling, a single national context, and self-reported measures, which are discussed in

Section 5.3. Future research could extend this work by comparing different cultural settings, examining additional outcome variables such as word-of-mouth or advocacy, and exploring longitudinal designs that track how AI-related beliefs and loyalty evolve as hotels deepen their use of AI. Despite these limitations, the findings highlight that creating an AI-enabled loyalty loop in hotels depends less on replacing humans and more on designing AI services that guests trust, experience as high-performing, and are ultimately willing to use as part of a broader, human-centred service experience.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.M. and Z.L.W.; methodology, I.M. and Z.L.W.; software, I.M. and Z.L.W.; validation, I.M., Z.L.W., and N.H.S.A.; formal analysis, I.M.; investigation, I.M.; resources, Z.L.W.; data curation, I.M.; writing—original draft preparation, I.M.; writing—review and editing, Z.L.W. and N.H.S.A.; visualisation, I.M.; supervision, Z.L.W.; project administration, Z.L.W.; funding acquisition, Z.L.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Research Ethics Committee at Whitireia and WelTec (protocol code RP433-2024, with approval date 13 August 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Beyari, H., & Hashem, T. (2025). The role of artificial intelligence in personalizing social media marketing strategies for enhanced customer experience. Behavioral Sciences, 15(5), 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilgihan, A., Ostinelli, M., Zhang, Y., & Lorenz, M. (2025). Artificial intelligence (AI) agents and the future of customer loyalty. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 37(9), 3240–3262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloemer, J., De Ruyter, K., & Wetzels, M. (1999). Linking perceived service quality and service loyalty: A multi-dimensional perspective. European Journal of Marketing, 33(11/12), 1082–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, R., Martínez, E., & Pérez, J. (2019). Effects of service experience on customer responses to a hotel chain. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 31(1), 389–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, A., & Holbrook, M. B. (2001). The chain of effects from brand trust and brand affect to brand performance: The role of brand loyalty. Journal of Marketing, 65, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, V., & Guo, R. (2021). The impact of consumers’ attitudes towards technology on the acceptance of hotel technology-based innovation. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology, 12(4), 624–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chotisarn, N., & Phuthong, T. (2025). Impact of artificial intelligence-enabled service attributes on customer satisfaction and loyalty in chain hotels: Evidence from coastal tourism destinations in western Thailand. Social Sciences and Humanities Open, 11, 101306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choung, H., David, P., & Ross, A. (2022). Trust in AI and its role in the acceptance of AI technologies. arXiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1992). Statistical power analysis. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 1(3), 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2017). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approach (5th ed.). Sage Publication. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewi, L., Wiranatha, A., & Suryawardani, I. (2021). Service quality, brand attributes, satisfaction and loyalty of guests staying at le meridien hotel bali jimbaran. E-Journal of Tourism, 8(1), 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorton, J., & Harper, R. (2022). A naturalistic investigation of trust, AI, and intelligence work. Journal of Cognitive Engineering and Decision Making, 16(4), 222–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H., Li, J., So, K. K. F., & King, C. (2025). Artificial intelligence in hospitality services: Examining consumers’ receptivity to unmanned smart hotels. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, 8(100), 55–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elziny, M., & Mohamed, H. (2022). The role of technological innovation in improving the Egyptian hotel brand image. International Journal of Heritage Tourism and Hospitality, 15(2), 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatma, M., & Rahman, Z. (2017). An integrated framework to understand how consumer-perceived ethicality influences consumer hotel brand loyalty. Service Science, 9(2), 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A. (2024). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics (6th ed.). SAGE Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbeinn, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Addison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Gajić, T., Ranjbaran, A., Vukolić, D., Bugarčić, J., Spasojević, A., Đorđević Boljanović, J., Vujačić, D., Mandarić, M., Kostić, M., Sekulić, D., Bugarčić, M., Drašković, B. D., & Rakić, S. R. (2024). Tourists’ willingness to adopt AI in hospitality—Assumption of sustainability in developing countries. Sustainability, 16(9), 3663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gall, M. D., Gall, J. P., & Borg, W. R. (2007). Educational research: An introduction (8th ed.). Pearson/Allyn & Bacon. [Google Scholar]

- Gatera, A. (2024). Role of artificial intelligence in revenue management and pricing strategies in hotels. Journal of Modern Hospitality, 3(2), 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, J., Wang, W., Guo, Z., Chan, J., & Qi, X. (2021). Customer experience and brand loyalty in the full-service hotel sector: The role of brand affect. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 33(5), 1620–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Sarstedt, M., Hopkins, L., & Kuppelwieser, V. G. (2014). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research. European Business Review, 26(2), 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Communication Monographs, 85(1), 4–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houtsman, M. J. (2020). Perceived AI performance and intended future use in AI based applications [Unpublished MA research]. Uppsala University. Available online: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1448732/FULLTEXT01.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Huang, M., & Rust, R. (2020). Engaged to a robot? the role of Ai in service. Journal of Service Research, 24(1), 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M., & Zhou, X. (2023). Unveiling the factors shaping consumer acceptance of AI assistant services in the hotel industry: A behavioral reasoning perspective. International Journal of Research in Business and Social Science (2147–4478), 12(9), 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, S., Gretzel, U., Berezina, K., Sigala, Μ., & Webster, C. (2019). Progress on robotics in hospitality and tourism: A review of the literature. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology, 10(4), 489–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, S. E., Ng, M., Hollowood, T., & Hort, J. (2018). Introduction to descriptive analysis. In S. E. Kemp, J. Hort, & T. Hollowood (Eds.), Descriptive analysis in sensory evaluation (pp. 1–39). John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H., Kim, W., & An, J. (2003). The effect of consumer-based brand equity on firms’ financial performance. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 20(4), 335–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J., Lee, J., & Han, H. (2022). Tangible and intangible hotel in-room amenities in shaping customer experience and the consequences in the with Corona era. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 35(2), 657–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leech, N. L., Barret, K. C., & Morgan, G. A. (2015). IBM SPSS for intermediate statistics: Use and interpretation (5th ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X., Hoo, W., Teck, T., Subramaniam, K., & Cheng, A. (2022). Relationship of customer engagement, perceived quality and brand image on purchase intention of premium hotel’s room. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 12(4), 768–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, A., & Yeung, M. (2019). Brand prestige and affordable luxury: The role of hotel guest experiences. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 26(2), 247–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manthiou, A., Kang, J., Sumarjan, N., & Tang, L. (2015). The incorporation of consumer experience into the branding process: An investigation of name-brand hotels. International Journal of Tourism Research, 18(2), 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marković, S., & Gjurašić, M. (2020). Creating personalized guest experience journey in leisure hotel. In ITEMA 2020: 4—Recent advances in information technology, tourism, economics, management and agriculture—Selected papers (pp. 31–45). Udruženje Ekonomista i Menadžera Balkana. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattila, A. (2006). How affective commitment boosts guest loyalty (and promotes frequent-guest programs). Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 47(2), 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcknight, D. H., Carter, M., Thatcher, J. B., & Clay, P. F. (2011). Trust in a specific technology: An investigation of its components and measures. ACM Transactions on Management Information Systems, 2(2), 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, A., & Russell, J. A. (1974). An approach to environmental psychology (pp. 216–217). The Massachusetts Institute of Technology. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, P., Pandey, C. M., Singh, U., Gupta, A., Sahu, C., & Keshri, A. (2019). Descriptive statistics and normality tests for statistical data. Annals of Cardiac Anaesthesia, 22(1), 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorman, C., Deshpandé, R., & Zaltman, G. (1993). Factors affecting trust in market research relationships. Journal of Marketing, 57(1), 81–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R. M., & Hunt, S. D. (1994). The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. Journal of marketing, 58(3), 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morosan, C. (2025). Rethinking information disclosure to GenAI in hotels: An extended parallel process model. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 124, 103965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngari, J. M., & Mwangi, Z. M. (2023). Technology orientation and sustained competitive advantage in star rated hotels in Kenya. The University Journal, 5, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R. L. (1999). Whence consumer loyalty. Journal of Marketing, 63, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Parasuraman, A. (2000). Technology readiness index (TRI) a multiple-item scale to measure readiness to embrace new technologies. Journal of Service Research, 2(4), 307–320. [Google Scholar]

- Pee, L. G., Jiang, J., & Klein, G. (2018). Signaling effect of website usability on repurchase intention. International Journal of Information Management, 39, 228–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelet, J., Lick, E., & Taieb, B. (2021). The internet of things in upscale hotels: Its impact on guests’ sensory experiences and behavior. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 33(11), 4035–4056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, L., Williamson, S., Lane, P., Limbu, Y., Nguyen, P., & Coomer, T. (2020). Technology readiness and purchase intention: Role of perceived value and online satisfaction in the context of luxury hotels. International Journal of Management and Decision Making, 19(1), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimian, S., Shamizanjani, M., Manian, A., & Esfidani, M. (2021). A framework of customer experience management for hotel industry. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 33(5), 1413–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Situmorang, S., & Aruan, D. (2021, February 20). The role of customer brand engagement on brand loyalty in the usage of virtual hotel operator. International Conference on Business and Engineering Management (ICONBEM 2021), Surabaya, Indonesia. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L., Swanson, S. R., & Chen, X. (2016). The effects of perceived service quality on repurchase intentions and subjective wellbeing of Chinese tourists: The mediating role of relationship quality. Tourism Management, 52, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štilić, A., Nicić, M., & Puška, A. (2023). Check-in to the future: Exploring the impact of contemporary information technologies and artificial intelligence on the hotel industry. Turisticko Poslovanje, 31(31), 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tussyadiah, I., Zach, F., & Wang, J. (2020). Do travelers trust intelligent service robots? Annals of Tourism Research, 81, 102886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, N., Upadhyay, S., & Dwivedi, Y. (2021). Theorizing artificial intelligence acceptance and digital entrepreneurship model. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour & Research, 28(5), 1138–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B., & Davis, F. D. (2003). User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Quarterly, 27(3), 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Višković, K., Rašan, D., & Prevolšek, D. (2023). Content analysis of TripAdvisor online reviews: The case of Valamar Riviera hotels in Dubrovnik. In Faculty of tourism and hospitality management in Opatija. Biennial international congress. Tourism & hospitality industry. University of Rijeka, Faculty of Tourism & Hospitality Management. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P. Q., Yan, L., & Santoso, C. (2025). Generational engagement with AI in hospitality: Human–AI interaction perspectives across the service process. Current Issues in Tourism, 28, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisker, Z. L., Kadirov, D., & Bone, C. (2019). Modelling P2P Airbnb online host advertising effectiveness: The role of emotional appeal information completeness creativity and social responsibility. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 13(4), 505–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisker, Z. L., Kadirov, D., & Nizar, J. (2020). Marketing a destination brand image to Muslim tourists: Does accessibility to cultural needs matter in developing brand loyalty? Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 47(1), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F., Sorokina, N., & Putra, E. (2023). Customers satisfaction on robots, artificial intelligence and service automation (RAISA) in the hotel industry: A comprehensive review. Open Journal of Business and Management, 11(03), 1227–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H., Law, R., Lovett, J., Luo, J. M., & Liu, L. (2024). Tourist acceptance of ChatGPT in travel services: The mediating role of parasocial interaction. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 41(7), 955–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yassin, E., Gharieb, A., Saad, H., & Qura, O. (2022). Robots, artificial intelligence, and service automation (RAISA) technologies in the Egyptian hotel sector: A current situation assessment. International Journal of Heritage Tourism and Hospitality, 16(1), 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B., Zhu, Y., Deng, Y., Zheng, W., Liu, Y., Wang, C., & Zeng, R. (2023). “I am here to assist your tourism”: Predicting continuance intention to use ai-based chatbots for tourism. does gender really matter? International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 39(9), 1887–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L., Sun, S., Law, R., & Zhang, X. (2020). Impact of robot hotel service on consumers purchase intention: A control experiment. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 25(7), 780–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).