1. Introduction

Tourism is a large business sector, a key engine for job creation, and a driving force for economic growth and development (

International Labour Organization, 2016). Tourist hotel activities result in large quantities and varieties of waste, which tend to expand as the number of hotels and tourists increases. Food waste represents the largest waste stream by weight in the hotel industry (

Filimonau & De Coteau, 2019). However, its management has become a concern, which calls for mitigation measures to avoid its detrimental effects on the socio-economic welfare and the environment (

Pirani & Arafat, 2016;

Mohan et al., 2017;

Eriksson et al., 2019). This not only requires technological and operational solutions but also effective stakeholder engagement to foster collaboration, knowledge exchange, information sharing, and coordinated actions toward sustainability.

Previous studies have investigated many aspects of food waste management, mostly with a focus on technology and political aspects, while only a few discussed the interactions of different stakeholders within the waste management systems (

Caniato et al., 2014;

Caniato et al., 2015;

W. Xu et al., 2016;

dos Muchangos et al., 2017;

X. Xu et al., 2024). Therefore, the recognition of stakeholders’ participation and engagement in waste management is significant to understand the complexity of human attitudes and behavior, both internally at the hotels and up- and down-stream within the waste value chain. From the perspective of stakeholder theory, hotels need to understand and account for all their stakeholders (

Irwansyah et al., 2022). The stakeholders may have a stake in the form of interest, influence, power, or participation in activities related to waste management. Stakeholder analysis of the waste management system gives importance to their respective knowledge and perception of the system, rather than focusing on observations by experts only.

Recent studies have also examined stakeholder collaboration and social interactions in managing sustainability challenges within the hospitality and tourism sector. This includes the work conducted in five-star hotels in Thailand, which examined stakeholder collaboration at different operational stages, anywhere from planning to donation, and the findings are tied with a theoretically grounded framework (food waste hierarchical principle), which provides both theoretical and applied insights (

Kattiyapornpong et al., 2023). Also, another study conducted in hotels in Langkawi, Malaysia, investigated sustainable hotel operators’ practices at island tourism destinations, emphasizing the importance of context-specific approaches (

Kasavan et al., 2017). In Australia, the empirical work investigated how stakeholder groups influence environmental sustainability strategies in the hotel industry (

Khatter et al., 2021); in addition, there was the research conducted in the hotel industry in China, which proposed a framework for stakeholder roles and engagement pathways in hotel environmental management, hence bridging the stakeholder theory and practical context (

Wang et al., 2024). These works illustrate research interest in context-driven stakeholder engagement models for sustainability and build this study’s foundation, which proposes a visual context-specific stakeholder engagement model tailored to micro-level networks in food waste management on small islands.

In the African context, stakeholder engagement in waste management is considered a new strategy and a driver for long-lasting support of societal decisions and actions. It promotes behavioral changes and taking responsibility for decisions that are important for functional waste systems (

Kaza & Bhada-Tata, 2018). Stakeholder engagement provides many benefits to environmental management research, including greater public acceptance, higher implementation success of interventions, wider communication of findings, and greater impact on decision-making, as well as improving the evidence base (

Haddaway et al., 2017).

The reference (

Stratoudakis et al., 2019) argued that engaging dominant players to change their conventional mentalities on traditional procedures leads to positive effects and allows for the construction of different types of capital, including the following: social (increase in trust and collaborations), human (new capacities and skills), intellectual (new knowledge and learning), and political (new services and infrastructures). Similarly, (

Vasconcelos et al., 2022) emphasized that stakeholders’ participatory processes are key for implementing innovative and sustainable waste prevention and management plans. This can ensure a mindset that also leads to a change in existing practices and influences their behavior.

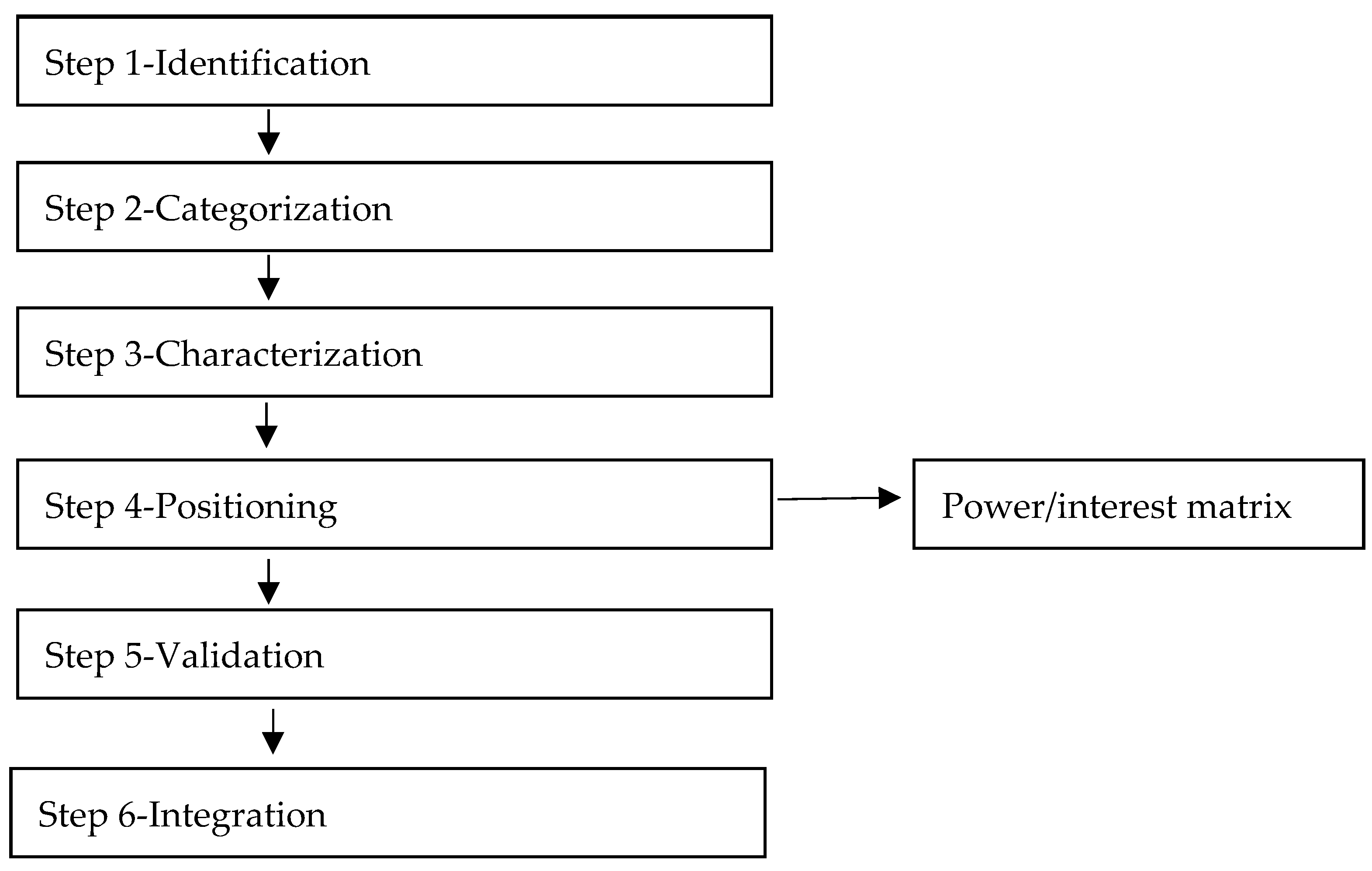

Stakeholder analysis is a process that is used to identify the influence of individual actors in relation to achieving the project outcome. This is accomplished through a desk review and participatory internal meetings or workshops, and, where appropriate, key informant interviews. The analysis aims to answer who the actors are and how they affect the project’s success or failure. Stakeholder analysis methods have three steps, which include stakeholder identification, classification, and investigation, to understand their characteristics (

W. Xu et al., 2016).

Furthermore, stakeholder analysis is based on the consideration that the system is driven by social roles and interaction, being strongly knowledge-based, with an important role in inter-organizational communication, information collection and sharing, and awareness of the current state-of-the-art and general situation (

Otchere et al., 2014;

Caniato et al., 2015). Stakeholder analysis and social network analysis are ways to study environmental, resource management, and public governance issues (

W. Xu et al., 2016). Social network analysis has the potential to examine the behavior and interaction of multiple stakeholders. A combination of stakeholder analysis and social network analysis is found to be beneficial in decision-making processes, to improve stakeholder engagement and enhance their network (

Caniato et al., 2014;

Caniato et al., 2015;

Lishan et al., 2021;

dos Muchangos et al., 2017).

On the other hand, stakeholders’ willingness to exchange information and their shared responsibility to organize, mobilize, participate, collectively prepare an action plan, and implement activities are considered crucial for taking effective measures regarding waste problems and the enhancement of governance activities (

Woldesenbet, 2021). The study also added that the structure of collaboration among stakeholders should consider the distribution of responsibility and power.

Effective communication and collaboration are crucial for the smooth operation of a hotel and the positive experience of its guests. A previous study conducted by (

Iwara et al., 2020) in Nigeria revealed a positive correlation between communication strategy and hotel performance, concluding that an effective communication strategy results in improved service quality and increased operational efficiency of a hotel (performance) and its competitiveness in the market. Therefore, regular communication should be conducted by hotel proprietors with their employees using different communication platforms, such as social media and face-to-face meetings. Similarly, (

Deshpande et al., 2024) elaborated that collaboration among staff, including front desk, housekeeping, and food services, is essential for providing a seamless and exceptional guest experience, resulting in a higher satisfaction rate. Successful collaboration and communication can be achieved in the organizational structure if the senior hotel managers call for macro-management over micro-management; in these instances, staff expect more autonomy and trust from senior management, and working environments that encourage open communication, which makes them feel comfortable sharing feedback and suggestions (

Borzillo & Alshahrani, 2024)

Moreover, the shift from a linear to a circular economic waste management system needs planning and close engagement of stakeholders at each stage of operations in the food service value chain to reduce the problem of food waste in tourism establishments. Hotels, as key components in the tourism industry, can commit to environmental sustainability in their business by complying with environmental standards, such as those highlighted in “Green Key”. “Green Key” is an internationally recognized certification system operating in many hospitality facilities in Europe and other parts of the world. The certificate is awarded to facilities and establishments that commit to sustainable business practices. Currently, more than 5000 hotels in more than 60 countries are “Green Key” certified (

Foundation for Environmental Education, 2023).

In Zanzibar, solid waste management remains a big challenge. According to the latest available official data, it is estimated that approximately 663 tons of solid waste are produced in Zanzibar per day (

Zanzibar Environmental Management Authority (ZEMA), 2019), with 80% generated by the hotels and restaurants catering to tourists (

World Travel & Tourism Council, 2017;

Revolutionary government of Zanzibar, 2020). Many tourist hotels are located in areas with rural characteristics and relatively low waste generation per capita. Therefore, most solid waste generated in these areas originates from the hotels. Hence, collective efforts and collaboration from all relevant stakeholders are required to enable systemic changes to improve the waste management system.

This study considers different stakeholders in relation to their roles, responsibilities, interests, knowledge, and power in decision-making, interactions, and influence on food waste management operations in tourist hotels. The current waste system is linear, with most waste generated being disposed of in landfills, which is the least preferred option for food waste. Hence, a change towards a more circular system demands the active engagement of all relevant stakeholders.

Although food waste in the hospitality sector has been investigated from operational perspectives, the focus has been on technical and managerial solutions. However, little is known about the contribution of stakeholder engagement and social networks in shaping waste management practices, particularly within tourist hotels in small island contexts. This study aims to map the key stakeholders and examine engagement dynamics and social network patterns in hotel food waste management. A stakeholder and network analysis was conducted as part of exploring and contextualizing food waste management in tourist hotels in Zanzibar. The study also considered how to establish communication platforms and forums for coordinated decision-making, thereby strengthening collaboration and information sharing among stakeholders—a feature currently lacking in the system. The absence of such knowledge has significant implications in Zanzibar, where tourism is the main driver of the economy and food waste poses both environmental and social challenges. Without clear evidence of how stakeholders contribute and interact, opportunities for coordinated action are missed, and policy risk is stated as a goal rather than an actionable measure, limiting the progress towards achieving the sustainability targets set out in Zanzibar’s vision for sustainable tourism articulated in the Zanzibar Sustainable Tourism Declaration. By addressing this gap, the study offers practical pathways to strengthen collaboration and partnerships among stakeholders, thereby supporting the island’s transition towards sustainability in the tourism sector. Therefore, the study contributes to the theoretical knowledge of stakeholder engagement, focusing on interaction, communication practices, and information-sharing mechanisms related to food waste management in tourist hotels.

Existing studies and models of stakeholder engagement provide broad frameworks that emphasize policy-level or institutional interactions and overlook the dynamics of micro-level interactions in the context of tourism food waste regarding tourism-dependent islands and destinations. In island contexts, where stakeholder networks are smaller and more interdependent, understanding the localized interactions, including those with hotels, suppliers, waste collectors, and the community, that directly influence the effectiveness of waste reduction and management strategies is essential, although not sufficiently explored in the current research. To address this gap, this study introduces a novel methodological model that integrates qualitative insights with social network analysis to capture micro-level stakeholder engagement dynamics in tourism food waste management; an approach not previously applied in this context. The study specifically introduces a model that offers a methodological innovation for analyzing and visualizing engagement dynamics within small-scale stakeholder networks, such as business or knowledge networks. This helps to increase our understanding of how stakeholders’ relationships influence collective actions, knowledge flow, and decision-making to achieve sustainability. The model also offers practical insights that can inform future stakeholder coordination, policy design, and collaborative strategies in sustainability-oriented initiatives. Unlike conventional models that remain descriptive or emphasize broad policy-level interactions, this study enhances methodological innovation by integrating qualitative insights from semi-structured interviews with social network analysis metrics to capture micro-level engagement dynamics. This combined approach provides a unique analytical and visual tool that makes visible the relative positions of stakeholders, the strength of their relationships, and the flow of knowledge and information in food waste management within tourism-dependent islands. By systematically applying this dual lens, the study contributes both a context-specific model and a transferable framework applicable to other small-scale, resource-constrained destinations facing similar sustainability challenges. This is the first study to develop and apply such an integrated stakeholder network model to tourism food waste management in island destinations, giving it a unique methodological contribution to the field.

3. Results

3.1. Stakeholder Identification

Based on the interviews with different stakeholders, the study identified various categories of stakeholders and arranged them in their respective networks. This included regulatory, business, local community, and knowledge networks as shown in

Table A1 (See

Appendix A). Together, these four networks complement each other by providing oversight, services, participation, and expertise, forming the foundation for a more integrated hotel solid waste management system.

The regulatory network comprises the central government and local government authorities. Interviews with stakeholders indicated that these stakeholders have the potential to influence all parts of the SWM system. Key central institutions include the following: Zanzibar Environmental Management Authority (ZEMA), overseeing national waste management; Zanzibar Commission for Tourism (ZCT), setting tourism regulations; and Zanzibar Investment Promotion Authority (ZIPA), which promotes and regulates investment projects, including hotel operations. At the local government level, district councils manage SWM within their areas, develop bylaws derived from national laws, and enforce both national and local regulations, giving them significant influence. Local leaders (shehas) in the community, appointed by regional commissioners, also form part of this governance structure.

Business networks include hotels and tourism organizations such as Zanzibar Association of Tourism Investors (ZATI), Hotel Association Zanzibar (HAZ), and Zanzibar Association of Tour Operators (ZATO). In addition, there are local tour operators linked to international companies, like TUI and Booking.com, whose pressures encourage sustainable practices. This group also includes private waste companies (ZANREC and Harm Garden), which provide hotel waste services, and Green Composting LTD, which is also considered to be part of the community network, as it engages local youth in making compost and reducing organic waste in the municipal waste streams.

The local community network comprises shehia members and some local waste collectors. The community is indirectly involved but strongly affected by hotel operations, particularly when waste is disposed of near villages. Overlaps in SWM activities expose communities to impacts, while keeping livestock offers untapped potential to reduce food waste in hotels through repurposing leftovers as animal feed.

The knowledge network includes government research departments, academic experts, and NGOs that support developing waste solutions through research, training, and environmental education. Key actors, such as the State University of Zanzibar (SUZA), collaborate with tourism stakeholders on SWM research and capacity building, while the Zanzibar Youth Education Development Support Association (ZAYEDESA) plays a significant role in environmental education and promotes eco-friendly practices at hotels.

3.2. Power, Knowledge, and Interest of Stakeholders

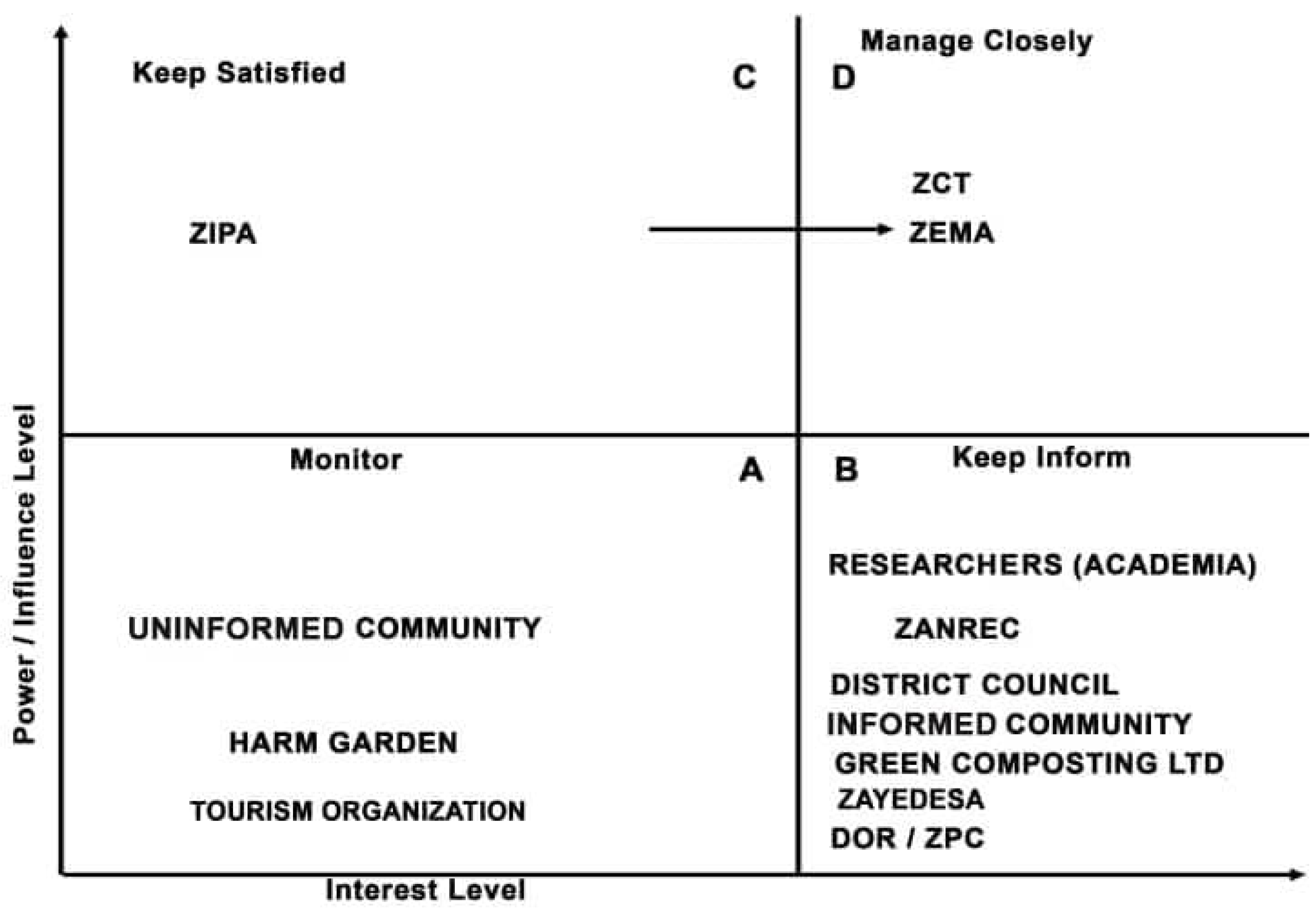

The power/interest matrix (

Figure 3) is used to visualize stakeholders related to hotel food waste management (FWM) and their classification in relation to power and interest, highlighting variations in influence, engagement, and potential roles in shaping sustainable food waste practices. Stakeholder groups are categorized into four predefined clusters. Stakeholders on the upper-right side of the grid have strong power and interest. The basis of defining these clusters is determined by the interest (concern) stakeholders have and how much power (authority) they have to change the waste management system into a more circular and sustainable system.

During interviews, it was revealed that ZEMA has the mandate to enforce and regulate environmental laws and has the highest power and interest in promoting sustainable FWM at hotels. The role of the institution is to ensure hotels’ compliance with laws, aiming to prevent pollution and ensure the safe disposal of waste: “We can intervene if the hotel waste disposal is not proper” (participant from ZEMA). The participant emphasized their responsibilities, reflecting the authority’s regulatory role in monitoring hotel practices and highlighting how government actors actively engage in safeguarding environmental standards to provide oversight accountability, which is linked to the identified theme of “Stakeholder roles and engagement”. The respondent also highlighted the low capacity of district councils to handle waste, explaining why the councils have decided to outsource waste management services to private companies. Similarly, the ZCT has played an active role in the Sustainable Tourism Declaration, which was endorsed in February 2023. Through the “Greener Zanzibar Campaign,” the ZCT aims to shift hotel practices toward more environmentally sustainable approaches, with a particular focus on sustainable waste management within tourism accommodations. As a regulatory body in the tourism sector, the ZCT possesses the authority to influence and drive change within the industry.

District councils, which are in charge of overseeing and supervising waste collection and disposal in their respective districts, expressed high interest but declared less power to act. They pointed out that issues related to hotel investment are more controlled by ZIPA: “We don’t have power, investment is under ZIPA” (respondent from district council). Based on the discussion with the respondent from the district council, ZIPA could be an important stakeholder since they are the ones issuing the license for the hotel facility investment and have a set of requirements for the construction of this kind of establishment. However, this government entity is reported to have less interest in issues related to waste management.

The private waste company ZANREC demonstrated high interest, despite having limited power to influence SWM practices. They abide by laws and work under contracts controlled by district councils. During the interview, the respondent from ZANREC expressed the following: “Our goal is to see sustainability of the island, so reducing the waste at hotels is a good thing for everyone, and will reduce dumping of waste within communities”. To justify the interest, the respondent also added the following: “We advise hoteliers to compost their food waste if they have enough space”. This highlights how stakeholder engagement contributes not only to improved hotel practices but also to wider communities and environmental outcomes linked to the identified theme of “Social and environmental outcomes of engagement”. Encouraging composting at hotels directly supports waste reduction, helps safeguard community spaces from illegal dumping, and aligns with broader sustainability goals of the island and tourism sector in particular. Additionally, the participant from ZANREC recommended that “there should be enforcement on where the waste should go after leaving the hotel”. In contrast, another waste company (Harm Garden) showed little interest in preventive and waste reduction initiatives at hotels and had limited knowledge in many aspects of food waste management.

Local communities are the stakeholders most directly affected by the impact of SWM from hotels. The participation of the community in solid waste management differs based on their level of awareness. The Kendwa community, which is more conscientious and knowledgeable, expressed high interest in food waste management practices, while the community without enough knowledge and awareness showed neither interest nor power. The Kendwa community was actively engaged in the waste management programs of the ZANREC waste management company, and the company provided incentives to children and women who participated in the program. For example, school children collected the plastic, and women were responsible for cleaning the environment outside the hotels’ gates.

A firm such as Green Composting LTD is a stakeholder that works in promoting food waste utilization. They have maximum interest in resource utilization, such as composting, but have low power. They could play a key role in scaling up food composting programs by making alliances with farmers in the community. Green Composting LTD is working with food and organic waste from hotels in Nungwi; however, they operate with a small number of hotels.

The active NGO ZAYEDESA is a member of the Foundation of Environmental Education (FEE). Again, this actor can be a catalyst for promoting action and change in the community, but does not have much power to act.

Tourism organizations such as ZATI are there to create a bridge between the government and the tourism industry. It is connecting actors through Fora and has the responsibility of pushing the government for regulations on behalf of the hotels. However, waste is not prioritized enough, and they do not exercise power over waste management. Given that most hotels are members of ZATI, the organization could be leveraged to ensure the implementation of sustainable SWM practices in hotels.

Finally, environmental experts, researchers, and academia can contribute with knowledge and technical support to promote practices regarding different aspects of food waste management. However, they have low power, although they are concerned.

Concerning knowledge, generally, all stakeholders have indicated some degree of knowledge regarding food waste management. However, their level of involvement and commitment to implementing changes was based on their role-specific accountability and responsibilities in the waste management system.

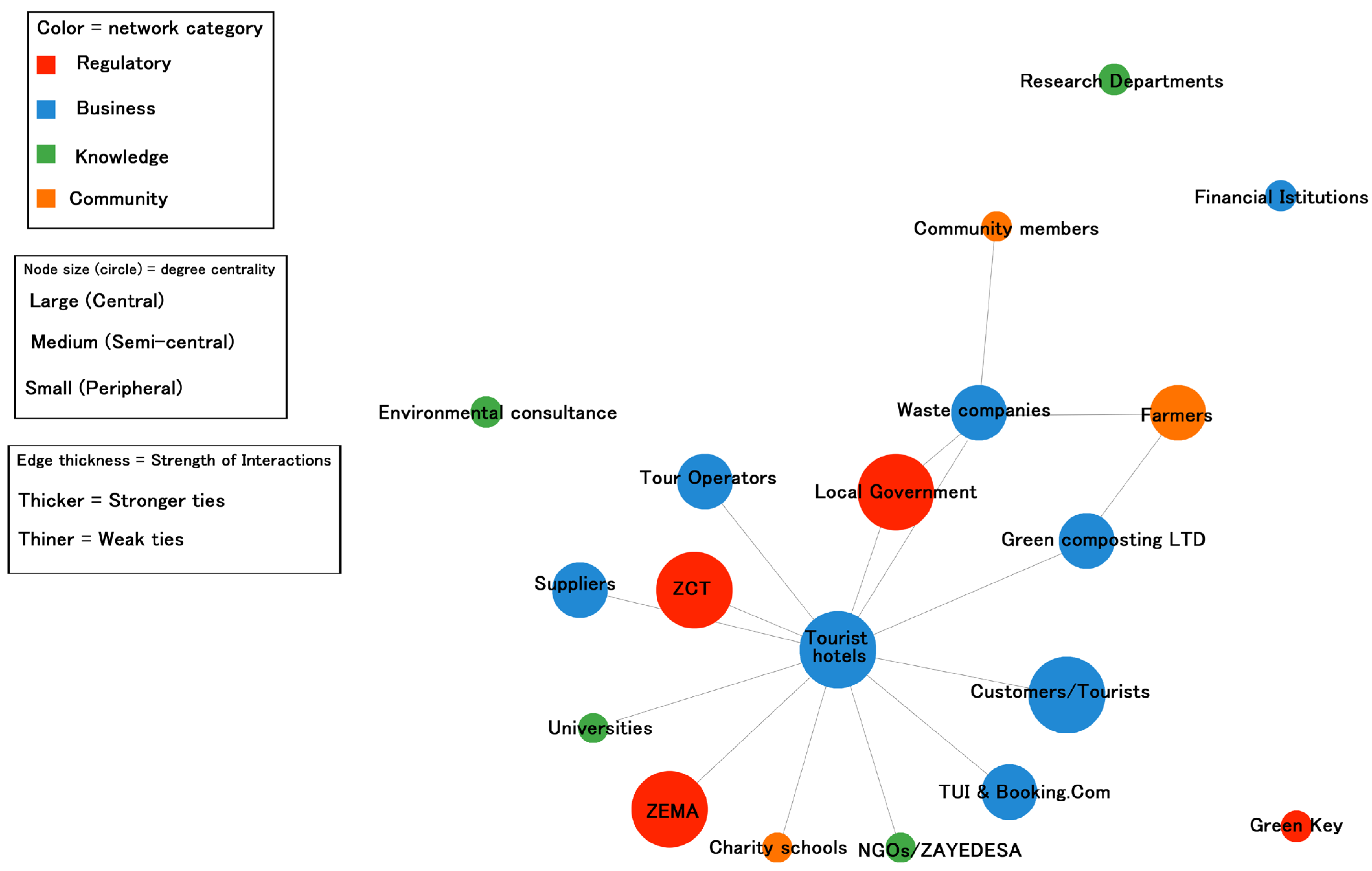

3.3. Collaboration, Communication, and Information Sharing Among Stakeholders

Figure 4 presents a network visualization of stakeholders in hotel food waste management. Node size indicates degree centrality (the level of connectedness), with larger circles indicating stakeholders that hold high influence/degree centrality (more direct connections). The network analysis revealed differentiated structures of stakeholder engagement in hotel food waste management, where central actors included hotels/managers, ZEMA, ZCT, local government, and customers/tourists due to their multiple, frequent, and influential connections across the network. Semi-central actors included suppliers, Green Composting LTD., waste companies, farmers, tour operators, and international booking platforms, such as TUI and Booking.com. These actors played important bridging or supportive roles, shaping upstream food supply, enabling circular economy practices, or influencing demand, but were less embedded than the central stakeholders, while peripheral stakeholders such as universities, research departments, environmental consultants, NGOs/ZAYEDESA, community members, charity schools, financial institutions, and green key were engaged in limited or indirect ways, through knowledge provision, certification, advocacy, or social support functions. Edge thickness reflects the relative strength of stakeholder relationships/interaction, as reported by respondents, where thicker lines indicate stronger, more frequent engagement and significant operational collaborations (e.g., hotels and waste companies, hotels and customers, hotels and regulators, or local government and waste companies), and thinner lines indicate weaker or less frequent ties (e.g., hotels and charity schools, and hotels and environmental consultants). This distribution indicates the centrality of hotels as the hub of the network, while also underscoring the role of semi-central bridging actors in connecting business, community, and regulatory networks. The figure illustrates the structural positions and relational dynamics of stakeholders within the network and complements the conceptual framework inspired by

Remmen and Holgaard (

2004) by adding quantitative dimensions to stakeholder engagement dynamics. According to this social network model, there was limited interaction between different sets of stakeholders, and regular communication was minimal (

Figure 3). When asked about the level of coordination and frequency of contact between them, one of the hoteliers commented the following: “We usually do not meet”. This sentence reflects the lack of coordinated forums or consistent interaction between hotels and other sectoral stakeholders. Limited contact undermines the flow of information and weakens opportunities for collective approaches to waste management, which relates to the theme of “Social network structures and dynamics”. During a workshop, the people of the community were also asked about their interaction with hoteliers and if there was any relationship. Group 1 members reported during the workshop that “we lack the meetings between us villagers and hoteliers” and group 1, 2 and 4 suggested on collaboration between them as one of the strategies to combat the waste problem, adding that “the actions can be taken through our environmental committee” (Respondent from group 2). The interviews revealed that the stakeholders tend to work in silos. Similarly,

Table A2 shows the categorization of stakeholders into high, moderate, or low across degree centrality, betweenness centrality, and density based on their relative positions, roles, and functions within the hotel food waste management network. Hotel/hotel managers and local government were assigned a high degree of centrality due to their multiple direct operational ties, while regulatory bodies, such as ZEMA and ZCT, hold high betweenness centrality because of their bridging roles between policy frameworks and industry actors. Local government and NGOs are considered strong and moderate brokers, respectively, linking formal institutions with community or sectoral interests. Universities and research institutes, although categorized as having a low degree of centrality due to fewer direct connections, contribute indirectly through knowledge transfer and innovation. These classifications are qualitative and context-specific, intended to illustrate relative stakeholder influence and cohesion.

In addition, it is evident that communication is lacking among key stakeholders. The findings also indicated that there are no coordinated platforms or structured forums for communication, information sharing, and decision-making among stakeholders regarding waste management in the tourist hotel industry in Zanzibar in general: “Our role is to facilitate needs; the rest is a government decision and no involvement of stakeholders for investments” (respondent from ZEMA). Discussions with various stakeholders revealed limited contact among the stakeholders. Stakeholders who are directly involved in waste management at hotels, such as district councils and private waste companies, met, although not regularly. Other stakeholders, especially between government entities and private organizations, had no significant interactions among them. Private entities had limited participation in issues related to waste management. District councils and ZEMA had a better understanding of the issues within the solid waste management system, unlike private sector stakeholders, who had limited knowledge and information and did not communicate regarding this issue.

Many stakeholders expressed the need for increased information sharing across different hierarchical levels and sectors. District councils were eager to share the issues of waste management with the higher authorities, such as ZEMA and ZIPA, who have comparatively higher power. In addition, social media could be an essential channel for sharing knowledge on food waste among the general public, though motivation regarding this was low for many stakeholders who were interviewed. The lack of these platforms and channels is a missed opportunity for sharing knowledge among the different stakeholders.

The study’s findings also highlighted the unfair treatment of hoteliers by waste management companies. Some hotels do their best to reduce waste generation, but private waste-collection companies continue to charge flat rates, regardless of the significant decrease in the collected waste. Hence, the hoteliers do not benefit.

3.4. Relationship Between Community and Hotels

The study has investigated how communities perceive waste management by the hotels and whether any relationship exists between hotels and the communities. Responses from the workshop revealed that all groups agreed that “some hotels are doing well with respect to their waste management”. One group commented that “in general the waste management is not good but there are some hotels, especially the big ones that are doing good. These hotels have hired special people to handle the waste, and they are connected to big waste companies such as ZANREC.”

The workshop participants maintained that there is no formal arrangement or agreement that exist regarding the relationship between the hotels and community, as one of the participant from group 1 said “we don’t have any formal agreement with hotels in relation to waste management” During the workshop, no examples of engagement in relation to waste management could be found, but usually local leaders (shehas) are engaged by hoteliers when there are social issues, such as social disputes or other corporate social responsibility activities, which demand a donation from hotels, such as water services to the villages. The above quote illustrates the informal and ad hoc nature of community–hotel relationships, which highlights the limited scope of community engagement and the reactive character of hotels’ interaction with local stakeholders. The absence of formalized agreements between hotels and communities suggests a structural barrier to collaboration, and without clear frameworks or consistent mechanisms for participation, communities remain marginal to decision-making in hotel waste management practices, which is reflected in the theme of “Barriers and challenges to effective engagement” In addition, the Kendwa community was engaged in cleaning the beach and areas outside the hotels’ gates under the operation of ZANREC. Cleaners outside the hotels were women, and they were paid by this waste company. In addition, ZURI Hotel in Kendwa initiated a plastic waste management program in collaboration with community members, especially women and school children. The aim of this program was to reduce litter in the surrounding communities. This would be attractive for tourists, as waste is always a major concern raised by tourists (guests suggest a tip box in hotels). The hotel manager commented that “We usually use one day at the end of the month for this program. We send our staff from the hotel to clean the environment together with the people from the community. It seems people become interested because now many community members get involved”.

Community workshop participants emphasized the importance of creating stronger and more structured platforms for joint action. One participant suggested that “there is a need for strengthening the existing collaboration between villagers and hotels e.g., environmental and health committee”. They proposed a tripartite collaboration between hotels, villages, and the government. Participants further proposed the establishment of structures and working instruments for reducing waste by stating the following: “There should be environment committees, unions (jumuiya) and establishments of small regulations and laws for anyone who goes against the environmental cleanliness”. This demonstrates how communities consider formal structures and clear rules as crucial enablers of effective collaboration. Establishing committees, unions, or local by-laws would not only institutionalize cooperation but also provide mechanisms for accountability, thereby creating opportunities for more sustainable and inclusive engagement across stakeholders.

3.5. Relationship Between Food Suppliers and Hotels

Hoteliers use suppliers for different food products, such as fruits and vegetables, fish, meat, poultry, dairy products, cereals, and dry goods. Hotels can source goods and services from local suppliers to support the local economy and reduce costs. However, interviews with hotel managers indicated limited interactions with local suppliers, except for the fish markets along the coast. It was noted that the big hotels engage food suppliers from Zanzibar town, while many small hotels purchase the ingredients directly from shops, supermarkets, and markets in town. This is largely to avoid the stringent procedures regarding tax payment through the Virtual Fiscal Device (VFD) system recently introduced by the Zanzibar Revenue Authority (ZRA). It was highlighted by managers during their interviews that they refrain from buying goods at local stores because the stores do not have the VFD, and nowadays, all receipts are required to be issued in an electronic format through the VFD system.

5. Conclusions

The study aimed at mapping and analyzing stakeholders to understand the dynamics of their engagement and interactions in the context of food waste management in tourist hotels to achieve sustainability goals. The study proposed a small-scale stakeholder systems model by mapping and categorizing stakeholders into tailored network types, such as business or knowledge networks, to facilitate understanding of their roles, interests, power, engagement goals, and communication flows. The findings have indicated a lack of coordination, limited communication, and information sharing among the stakeholders. The interest, power, and knowledge of stakeholders are factors that affect their motivation to take on their roles and responsibilities, especially when it comes to participating in food waste management programs, such as the redistribution of surplus food and recycling.

Many stakeholders with high interest, such as Green Composting LTD, do not have sufficient power to influence any changes in the current take-make-disposal system. The local government has the main responsibility for solid waste management, including food waste, but has not set up any requirements for hotels and waste management companies with regard to sustainability. So far, private waste management companies are collecting food waste from hotels and transporting it to dumpsites, which adds to the problem of mixed waste at the site. Therefore, they need to be provided with incentives, such as the provision of space for composting and for making separation a necessary requirement for hoteliers before final disposal of non-recyclable residuals at a landfill.

Decision-making processes are characterized by complex interactions between different actors and sectors. Therefore, building social interactions among upstream and downstream stakeholders will enhance their engagement in the practical implementation of the initiated program and significantly impact system functioning. Small-scale stakeholder interactions, such as business or knowledge networks, are effective in building collaborative relationships and partnerships towards sustainable food waste management initiatives in the sector. Information and knowledge sharing are key to building such a network. In addition, the network between stakeholders, such as researchers and decision-makers, can become a bridge to share knowledge and information that could influence policy changes and practices downstream.

Community engagement and understanding the mechanism of extending interactions between hoteliers and communities are essential steps towards the success of grassroots initiatives. Community members can be potential agents for improvement while promoting income generation and supporting their livelihood through waste reduction and recovery programs. These options are preferred in the food waste management hierarchy over disposal in a landfill. Similarly, increased interactions and communication between management and hotel staff can enhance the implementation of prevention and waste reduction programs at hotels. This can help the staff develop their sense of duty and commitment in their daily routines and responsibilities.

In conclusion, effective engagement and interactions of stakeholders result in positive effects on social processes, such as inclusive decision-making, building trust and collaboration, accountability, and institutional relationships, which also lead to the improvement of environmental and economic outcomes. Moreover, the study offers practical insights that can guide practitioners or policymakers in forming effective collaborations or interventions.