Stakeholders’ Involvement in Sustainable Destination Management: A Systematic Literature Review of Existing Multi-Stakeholder Frameworks and Approaches

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Involvement of Stakeholders

2.2. Participatory Governance

2.3. Multi-Stakeholder Frameworks

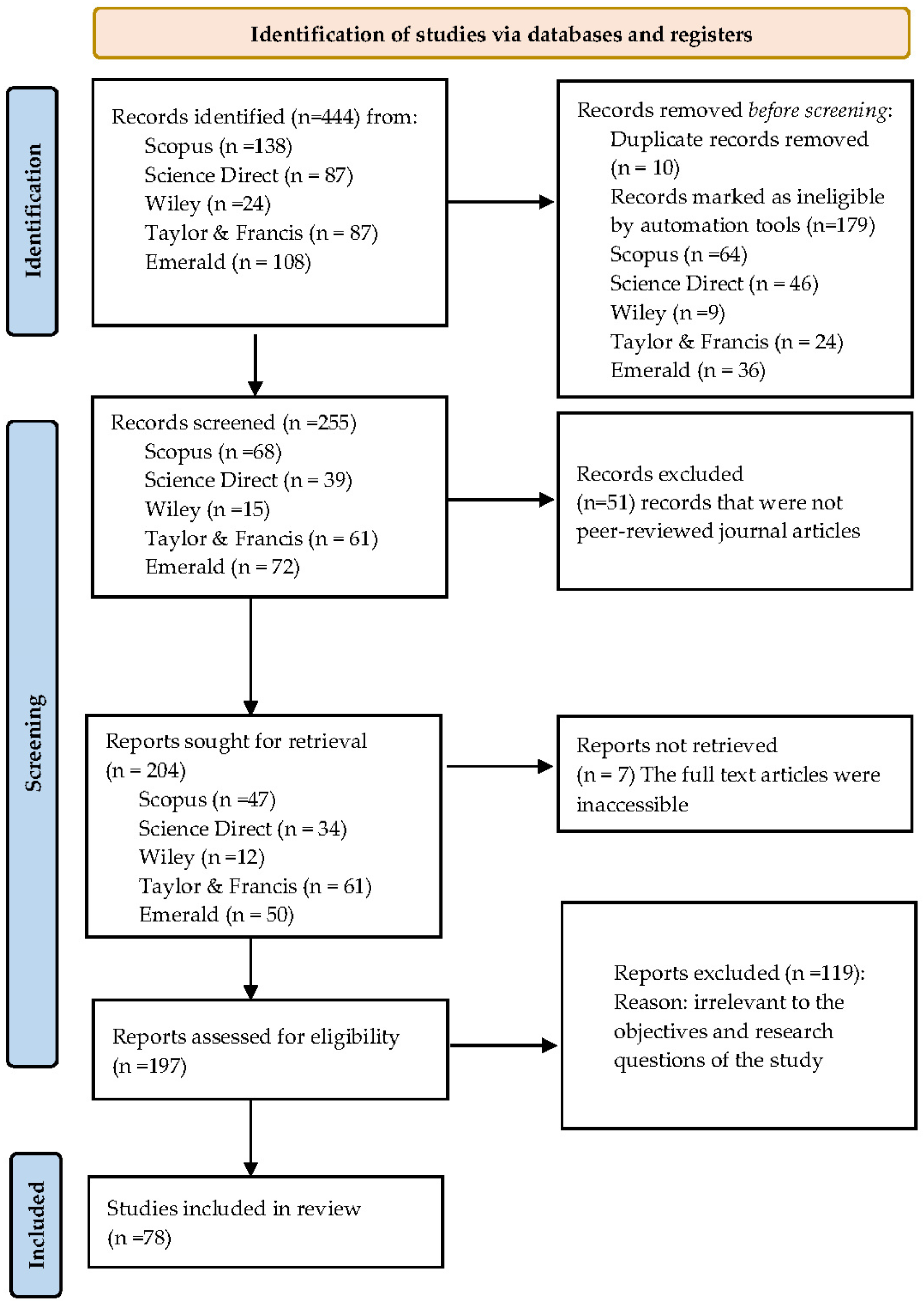

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Questions

3.2. Search Procedure

3.3. Analysis of the Results

- Stage 1: Typological classification of the sample

- Stage 2: Selection of a subset for comparative study

- Stage 3: Coding and Matrix Formation

4. Results

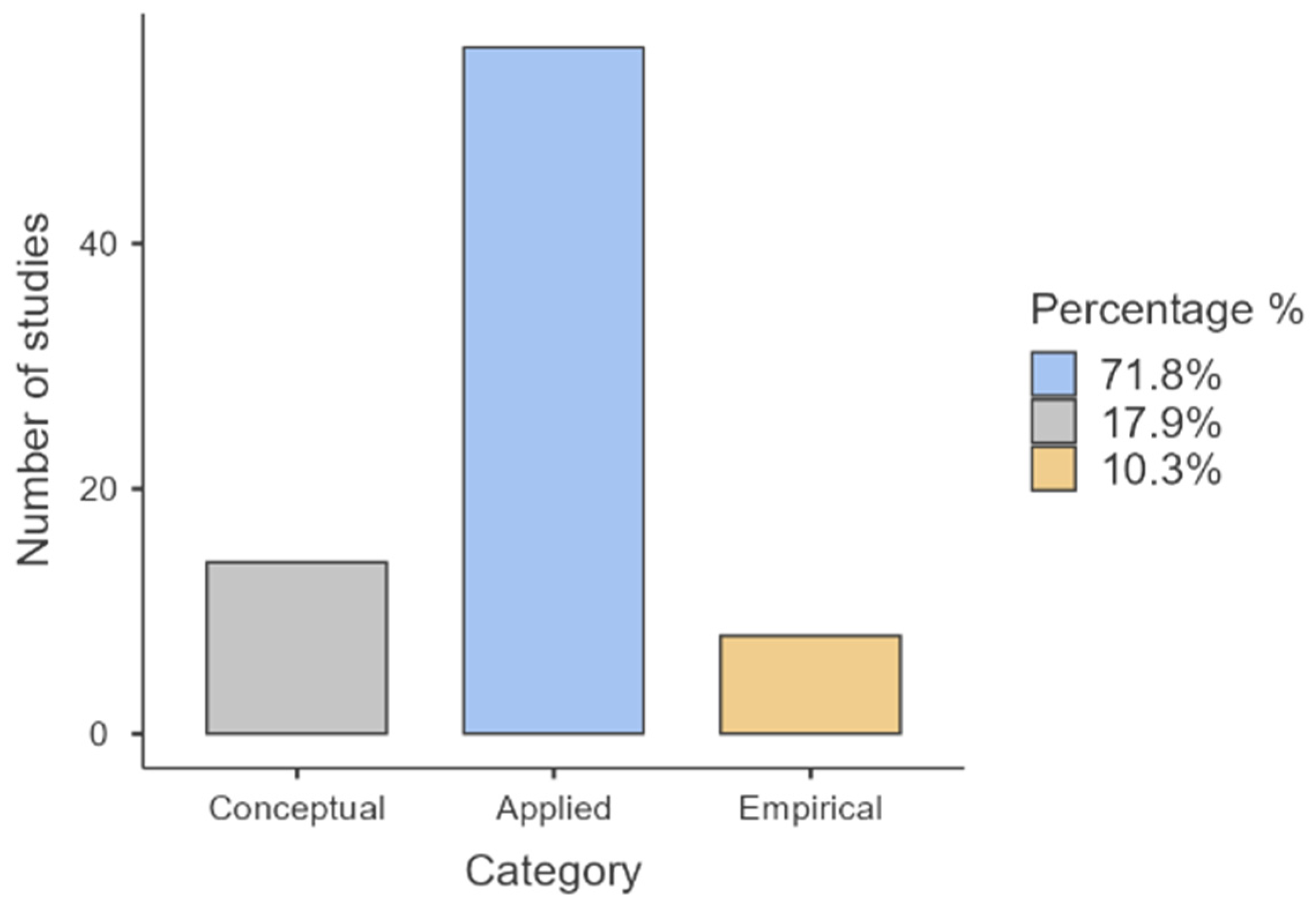

4.1. Typological Distribution of Sample

4.2. The Subset (n = 6)

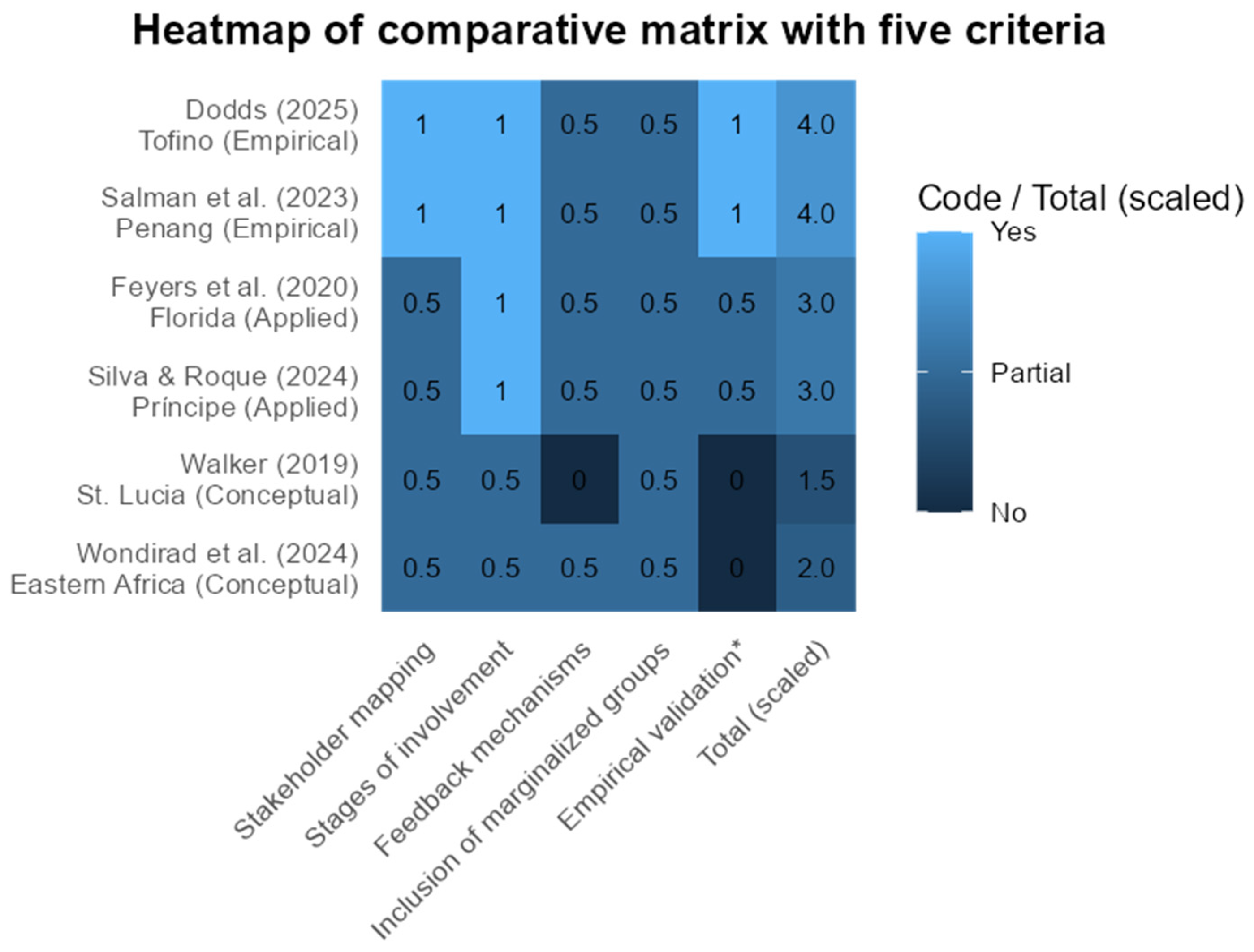

4.3. The Comparative Matrix

4.4. Destination Profile Categorization

- Mature institutional support: Destinations with mature institutional support from an organization or coordinator of the process, where the framework is adapted through standardized stages and engagement routines for stakeholders, as presented in studies on Penang Hill (Salman et al., 2023) and Florida (Feyers et al., 2020).

- Long-term partnerships: Destinations that have long-term relationships and partnerships, enabling empirical evaluation and repeated learning, as with the case of Tofino (Dodds, 2025).

- Emerging governance: Destinations that share characteristics of small island developing states with limited administrative resources, such as Príncipe Island (F. Silva & Roque, 2024), tend to approach framework adaptation from a pragmatically achievable base. In these contexts, progress typically begins with doable first steps and the early involvement of key stakeholders, prioritizing feasibility and incremental consolidation over comprehensive, data-heavy reform.

5. Discussion

5.1. Differences in the Key Features and Applications of Collaborative Approaches or Frameworks

5.2. Adaptation of Core Elements, Operational Mechanisms, and Foundational Principles of Frameworks and Collaborative Approaches on the Destinations’ Actual Conditions

5.3. Challenges and Barriers

6. Conclusions

- Mapping and staging now appear as near-standard practice, whereas feedback, inclusion, and validation remain the main maturity gaps: The predominance of applied case studies in the corpus helps explain recurring weaknesses in frameworks’ treatment of feedback mechanisms, measurable inclusion of marginalized groups, and empirical validation. Using the maturity matrix, the study further proposes a categorization that reflects each framework’s level of maturity. Empirical cases tend to present a more complete configuration across the five criteria and therefore achieve higher overall scores than applied case studies and conceptual models.

- Institution-rich settings tend to standardize existing practices, while capacity-thin settings progress through doable first steps and incremental consolidation toward sustainability: The comparative matrix supports grouping the cases into three typical destination settings (mature institutional support, long-term partnerships, emerging governance), providing a clearer picture of how frameworks operate given destination-specific characteristics. This study, through the three context profiles in combination with the two design levers, offers a practical tool, with which destinations can move from good intentions to a first actionable step toward sustainability via multi-stakeholder approaches and iteratively adapt their practices to advance to higher levels of maturity.

- The two design levers (intermediation capacity and institutionalized learning) function as enhancement mechanisms, regardless of the initial governance framework: The most successful examples of frameworks are well-organized, fully structured, and tailored to destination conditions. They combine predefined stages with flexibility, enabling learning-by-doing and adaptation over time. Two complementary design levers (intermediation capacity and institutionalized learning) function as upgrading mechanisms that destinations can activate irrespective of context.

6.1. Contribution of the Study

6.2. Limitations of the Study and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Materials and Methods

| Database | Common Search String | Date of Search | Applied Filters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scopus | (“multi-stakeholder framework” OR “collaborative framework” OR “participatory governance”) AND (“sustainable tourism” OR “sustainable destination” OR “destination development”) | 17 June 2025 | Search within = article title, abstract, keywords; Range = 2014–2025; Subject area = Social Sciences and Business, Management and Accounting; Document Type = Article; Language = English |

| ScienceDirect | 18 June 2025 | Years = 2014–2025; Article type = Review articles, Research articles; Subject area = Social Sciences and Business, Management and Accounting | |

| Wiley | 18 June 2025 | Publication type = journals; Publication date = 2014–2025 | |

| Taylor & Francis | 18 June 2025 | Article type = Article; Publication date = 2014–2025 | |

| Emerald | 19 June 2025 | Years = 2014–2025; Content type = article |

| Criteria | Content | Yes | Partial | No |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stakeholder mapping | Explicit identification of actors, including primary and secondary, with roles/relationships. | Systematic map covering primary and secondary actors plus roles/coordination structure and an identification method or scope rationale. | Only “major” actors listed and/or roles/relationships or method are unclear. | Generic mention of “stakeholders” with no specifics. |

| Stages of involvement | Sequenced participation (inform → consult → co-design/co-production) with clear transitions. | Named phases with who/when/tools and transition criteria or milestones. | Some phases/tools exist but sequencing/transition criteria are unclear. | Ad hoc engagement without a designed sequence. |

| Feedback mechanisms | Monitoring–evaluation loops used for learning/adaptation. | Named, periodic M&E cycles (e.g., quarterly/annual) and documented use of findings for adjustments. | One-off or informal feedback; sporadic assessments without routine use. | No documented feedback/M&E mechanism. |

| Inclusion of marginalized groups | Targeted participation and measured benefits for under-represented groups. | Targeted actions and disaggregated indicators (participation/benefit) tracked over time. | Inclusion is mentioned or attempted but without indicators/time-tracking. | No specific provision or measurement for marginalized groups. |

| Empirical validation | Explicit testing of the framework itself with systematic data. | Pre-specified criteria/indicators and an evaluation design (mixed/before–after/longitudinal) leading to conclusions about the framework’s effectiveness/refinement. | Data are collected, but do not explicitly evaluate the framework’s effectiveness. | No testing/measurement of the framework. |

| Study | Stakeholder Mapping | Stages of Involvement | Feedback Mechanisms | Inclusion of Marginalized Groups | Empirical Validation | Total (0–5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wondirad et al. (2024) Eastern Africa | PARTIAL (0.5): discuss multi-level and participatory governance but without any mapping method | PARTIAL (0.5): basic principles for engagement are mentioned but without any staged sequence | PARTIAL (0.5): support adaptive governance but without any specific feedback loops | PARTIAL (0.5): Inclusion of indigenous knowledge but without any targeted indicators or tracking | NO (0): no empirical testing or assessment | 2 |

| Walker (2019) St. Lucia, Caribbean | PARTIAL (0.5): mentions festival actors but lacks systematic mapping with roles | PARTIAL (0.5): describes engagement around festival planning but without talking about any formal staged sequence with criteria | NO (0): no documented feedback mechanisms | PARTIAL (0.5): Community benefits mentioned but does not mention or use of indicators or measures for marginalized groups | NO (0): no framework testing | 1.5 |

| F. Silva and Roque (2024) Príncipe Island | PARTIAL (0.5): Key partners described and engaged but without any mapping method | YES (1): Four-phase approach described: conceptual model, resource inventory, expert evaluation, product development | PARTIAL (0.5): Expert review and inventory. No specific feedback circle or documented routine | PARTIAL (0.5): Community benefits mentioned and participation emphasized but without any indicators or formal tracking of marginalized groups | PARTIAL (0.5): Expert scoring and field inventory but without any formal test of the framework’s effectiveness | 3 |

| Feyers et al. (2020) Florida, USA | PARTIAL (0.5): Mentions stakeholders (DMOs, TDCs, park managers, tourism providers, etc.) and a broader secondary audience but without any systematic mapping | YES (1): MSIM in scene-setting, integration, implementation steps with specified activities | PARTIAL (0.5): feedback is event-based but without monitoring and evaluation routine | PARTIAL (0.5): community representatives included but without any specific indicators for marginalized groups | PARTIAL (0.5): without any explicit before-after test of the MSIM effectiveness | 3 |

| Dodds (2025) Tofino, Canada | YES (1): multi-actors set (residents, employees, NGOs, etc.) with description of roles across governance | YES (1): Description of longitudinal phases and shows stages governance shifts | PARTIAL (0.5): reports member-checking and iterative synthesis but without formal use of the routines followed | PARTIAL (0.5): Indigenous inclusion reported but there are not any broader vulnerable groups indicators | YES (1): evaluation of framework over 15 years with outcomes | 4 |

| Salman et al. (2023) Penang Hill, Malaysia | YES (1): roles and responsibilities are described for various stakeholders (agencies, operators, residents, Penang Hill Corporation-led stakeholders) | YES (1): Structured engagement activities integrated in management process | PARTIAL (0.5): engagement events described but without any specific monitoring and evaluation circle | PARTIAL (0.5): Whole community mentioned but without any marginalized groups indicators | YES (1): use of statistical tests for stakeholder-management relationships | 4 |

Appendix B. Results

| Study | Category | Stakeholder Mapping | Stages of Involvement | Feedback Mechanisms | Inclusion of Marginalized Groups | Empirical Validation | Total (0–5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wondirad et al. (2024) Eastern Africa | Conceptual model | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0 | 2 |

| Walker (2019) St. Lucia, Caribbean | Conceptual model | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 1.5 |

| F. Silva and Roque (2024) Príncipe Island | Applied case study | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 3 |

| Feyers et al. (2020) Florida, USA | Applied case study | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 3 |

| Dodds (2025) Tofino, Canada | Empirically evaluated framework | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 4 |

| Salman et al. (2023) Penang Hill, Malaysia | Empirically evaluated framework | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 4 |

References

- Abdullah, T., Lee, C., & Carr, N. (2022). Conceptualising human and non-human marginalisation in tourism. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 23(2), 254–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arifin, S., Azinuddin, M., Mat Som, A., Ibrahim, A., & Hanafiah, M. H. (2025). Collaborative communication for sustainable tourism in Asia: A case study from Madura Island. Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes, 17(3), 413–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boaz, A., Grayson, L., Levitt, R., & Solesbury, W. (2008). Does evidence-based policy work? Learning from the UK experience. Evidence & Policy, 4(2), 233–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornhorst, T., Ritchie, B. J. R., & Sheehan, L. (2010). Determinants of tourism success for DMOs & destinations: An empirical examination of stakeholders’ perspectives. Tourism Management, 31(5), 572–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramwell, B., & Lane, B. (2005). From niche to general relevance?: Sustainable tourism, research and the role of tourism journals. Journal of Tourism Studies, 16(2), 52–62. [Google Scholar]

- Brokaj, R., & Murati, M. (2014). Sustainable tourism development in Albania through stakeholders’ involvement. Academic Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies, 3(2), 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrd, E. T. (2007). Stakeholders in sustainable tourism development and their roles: Applying stakeholder theory to sustainable tourism development. Tourism Review, 62(2), 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canellas, S., Ritto, F. G., Rodolico, A., Aguglia, E., de Oliveira Fernandes, G. V., da Silva Figueredo, C. M., & Vettore, M. V. (2022). The international platform of registered systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (INPLASY®) at two years: An analysis of 3,082 registered protocols on inplasy.com, platform features, and website statistics. Research Square. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, D. J., Mulrow, C. D., & Haynes, R. B. (1997). Systematic reviews: Synthesis of best evidence for clinical decisions. Annals of Internal Medicine, 126(5), 376–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossan, M. M., & Apaydin, M. (2010). A multi-dimensional framework of organizational innovation: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Management Studies, 47(6), 1154–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damian, I. M., Navarro-Jurado, E., & Ruiz, F. (2021). Involving stakeholders in the evaluation of the sustainability of a tourist destination: A novel comprehensive approach. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 31(7), 1631–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Angella, F., De Carlo, M., & Sainaghi, R. (2010). Archetypes of destination governance: A comparison of international destinations. Tourism Review, 65(4), 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, R. (2025). Balancing tourism development and sustainability: A multi-stakeholder approach in Tofino over 15 years. Sustainability, 17(2), 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domorenok, E., Graziano, P., & Polverari, L. (2021). Introduction: Policy integration and institutional capacity: Theoretical, conceptual and empirical challenges. Policy and Society, 40(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dredge, D., & Jenkins, J. (Eds.). (2016). Stories of practice: Tourism policy and planning. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farsari, I., Butler, R. W., & Szivas, E. (2011). Complexity in tourism policies. Annals of Tourism Research, 38(3), 1110–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feyers, S., Stein, T., & Klizentyte, K. (2020). Bridging worlds: Utilizing a multi-stakeholder framework to create extension–tourism partnerships. Sustainability, 12(1), 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font, X., Torres-Delgado, A., Crabolu, G., Palomo Martinez, J., Kantenbacher, J., & Miller, G. (2021). The impact of sustainable tourism indicators on destination competitiveness: The European tourism indicator system. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 31(7), 1608–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fyall, A., & Garrod, B. (2005). Tourism marketing: A collaborative approach. Channel View Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Gasparini, M. L., & Cortés Vázquez, J. A. (2024). Towards a European governance framework for pilgrimage routes: Challenges, opportunities and recommendations. ARROW@TU Dublin. Available online: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/ijrtp/vol12/iss2/3/ (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- Gonzalez-Urango, H., & García-Melón, M. (2018). Stakeholder engagement to evaluate tourist development plans with a sustainable approach. Sustainable Development, 26(6), 800–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graci, S. (2013). Collaboration and partnership development for sustainable tourism. Tourism Geographies, 15(1), 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gretzel, U., Fesenmaier, D. R., Formica, S., & O’Leary, J. T. (2006). Searching for the future: Challenges faced by destination marketing organizations. Journal of Travel Research, 45(2), 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C. M., & Veer, E. (2016). The DMO is dead. Long live the DMO (or, why DMO managers don’t care about post-structuralism). Tourism Recreation Research, 41(3), 354–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F., & Bigby, B. C. (2022). A local turn in tourism studies. Annals of Tourism Research, 92, 103291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivars-Baidal, J., Casado-Díaz, A. B., Navarro-Ruiz, S., & Fuster-Uguet, M. (2024). Smart tourism city governance: Exploring the impact on stakeholder networks. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 36(2), 582–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katemliadis, I., & Markatos, G. (2021). Stakeholders’ involvement in sustainability planning and implementation: The case of Cyprus. Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes, 13(6), 709–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladkin, A., & Bertramini, A. M. (2002). Collaborative tourism planning: A case study of Cusco, Peru. Current Issues in Tourism, 5(2), 71–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonidou, E., Christofi, M., Vrontis, D., & Thrassou, A. (2020). An integrative framework of stakeholder engagement for innovation management and entrepreneurship development. Journal of Business Research, 119, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messiou, K. (2011). Collaborating with children in exploring marginalisation: An approach to inclusive education. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 16(12), 1311–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Methley, A. M., Campbell, S., Chew-Graham, C., McNally, R., & Cheraghi-Sohi, S. (2014). PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: A comparison study of specificity and sensitivity in three search tools for qualitative systematic reviews. BMC Health Services Research, 14(1), 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, A. M. (2023). Marketing and managing tourism destinations (3ο έκδ.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, J. (2019). Towards achieving broadened accountability: Transcending governance dilemmas. SSRN Electronic Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T. Q. T., & Hoang, T. T. H. (2023). Stakeholder involvement and the attainment of SDGs at local tourism destinations: A case study in Vietnam. Tourism: An International Interdisciplinary Journal, 71(3), 432–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T. Q. T., Nguyen, V. T., Hoang, T. T. H., Tran, T. H. T., & Nguyen, T. P. T. (2024). Social networking, environmental awareness and sustainable tourism development in Da Nang, Vietnam. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 25(3), 475–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niavis, S., Papatheochari, T., Psycharis, Y., Rodriguez, J., Font, X., & Martinez Codina, A. (2019). Conceptualising tourism sustainability and operationalising its assessment: Evidence from a mediterranean community of projects. Sustainability, 11(15), 4042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigg, J. J., & Eichelberger, S. (2021). Sustainable product development for accessible tourism: Case studies demonstrating the need for stakeholder collaboration. Sustainability, 13(20), 11142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsen, P. (2015). Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implementation Science, 10, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paulino, I., Burgos-Tartera, C., & Aulet, S. (2023). Participatory governance of intangible heritage to develop sustainable rural tourism: The timber-raftsmen of La Pobla de Segur, Spain. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 18(5), 710–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, K., Andereck, K. L., & Vogt, C. A. (2023). Stakeholders’ involvement in an evidence-based sustainable tourism plan. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 33(4), 673–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, C., & Byrne, J. (2013). The benefits of publishing systematic quantitative literature reviews for PhD candidates and other early-career researchers. Higher Education Research & Development, 33(3), 534–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, S., & Page, S. J. (2014). Destination marketing organizations and destination marketing: A narrative analysis of the literature. Tourism Management, 41, 202–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plummer, R., Baird, J., Bullock, R., Dzyundzyak, A., Dupont, D., Gerger Swartling, Å., Johannessen, Å., Huitema, D., Lyth, A., de Lourdes Melo Zurita, M., Munaretto, S., Smith, T., & Thomsen, D. (2018). Flood governance: A multiple country comparison of stakeholder perceptions and aspirations. Environmental Policy and Governance, 28(2), 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queiroz, S. F. (2009). Stakeholders’ theory and its contribution to the sustainable development of a tourism destination. WIT Transactions on Ecology and the Environment, 120, 791–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S. M., Ramakrishna, S., Hall, C. M., Esfandiar, K., & Seyfi, S. (2020). A systematic scoping review of sustainable tourism indicators in relation to the sustainable development goals. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 31(7), 1497–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M. S. (2008). Stakeholder participation for environmental management: A literature review. Biological Conservation, 141(10), 2417–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reggers, A., Grabowski, S., Wearing, S. L., Chatterton, P., & Schweinsberg, S. (2016). Exploring outcomes of community-based tourism on the Kokoda Track, Papua New Guinea: A longitudinal study of participatory rural appraisal techniques. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 24(8–9), 1139–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roxas, F. M. Y., Rivera, J. P. R., & Gutierrez, E. L. M. (2020). Mapping stakeholders’ roles in governing sustainable tourism destinations. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 45, 387–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruhanen, L. (2009). Stakeholder participation in tourism destination planning: Another case of missing the point? Tourism Recreation Research, 34(3), 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruhanen, L. (2013). Local government: Facilitator or inhibitor of sustainable tourism development? Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 21(1), 80–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, C. (2002). Equity, management, power sharing and sustainability—Issues of the ‘new tourism’. Tourism Management, 23(1), 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, A., Jaafar, M., Mohamad, D., Khoshkam, M., Rahim, R. A., & Mohd, A. (2023). Stakeholder management for sustainable ecotourism destinations: A case of Penang Hill Malaysia. Journal of Ecotourism, 23(4), 563–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarantakou, E., & Karachalis, N. G. (2024). Σχεδιασμός και διαχείριση τουριστικών προορισμών: Στρατηγικές και χωρικές προσεγγίσεις [Design and management of tourist destinations: Strategic and spatial approaches]. Kritiki Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, A., & Arora, S. (2024). Understanding the role of stakeholders in sustainability of travel and tourism industry: Future prospects. In A. Sharma (Ed.), International handbook of skill, education, learning, and research development in tourism and hospitality. Springer international handbooks of education. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheehan, L., Vargas-Sánchez, A., Presenza, A., & Abbate, T. (2016). The use of intelligence in tourism destination management: An emerging role for DMOs. International Journal of Tourism Research, 18(6), 549–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, F., & Roque, M. (2024). Building the framework for sustainable tourism in Príncipe Island. Tourism and Hospitality, 5(1), 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L. F., Carballo-Cruz, F., & Ribeiro, J. C. (2024). Residents’ perceptions of tourism development in the context of a new governance framework for Portuguese protected areas: The case of a small peripheral natural park. Journal of Rural Studies, 112, 103451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smit, B., Melissen, F., Font, X., & Dickinger, A. (2024). Destination design: Identifying three key co-design strategies. Current Issues in Tourism, 27(24), 4791–4806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, H. (2019). Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines. Journal of Business Research, 104, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawfik, G. M., Dila, K. A. S., Mohamed, M. Y. F., Tam, D. N. H., Kien, N. D., Ahmed, A. M., & Huy, N. T. (2019). A step by step guide for conducting a systematic review and meta-analysis with simulation data. Tropical Medicine and Health, 47(1), 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tham, A. (2018). Sand, surgery and stakeholders: A multi-stakeholder involvement model of domestic medical tourism for Australia’s sunshine coast. Tourism Management Perspectives, 25, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Towner, N. (2018). Surfing tourism and local stakeholder collaboration. Journal of Ecotourism, 17(3), 268–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez-Brust, D., Piao, R. S., de Melo, M. F. d. S., Yaryd, R. T., & Carvalho, M. M. (2020). The governance of collaboration for sustainable development: Exploring the “black box”. Journal of Cleaner Production, 256, 120260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivier, E., & Sanchez-Betancourt, D. (2023). Participatory governance and the capacity to engage: A systems lens. Public Administration and Development, 43(3), 220–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volgger, M., & Pechlaner, H. (2014). Requirements for destination management organizations in destination governance: Understanding DMO success. Tourism Management, 41, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volgger, M., & Pechlaner, H. (2015). Governing networks in tourism: What have we achieved, what is still to be done and learned? Tourism Review, 70(4), 298–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waligo, V. M., Clarke, J., & Hawkins, R. (2013). Implementing sustainable tourism: A multi-stakeholder involvement management framework. Tourism Management, 36, 342–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, T. B. (2019). Sustainable tourism and the role of festivals in the Caribbean—Case of the St. Lucia Jazz (& arts) festival. Tourism Recreation Research, 44(2), 258–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wondirad, A., Ma, Y., & Tolkach, D. (2024). Tourism governance in the new normal: Lessons for Eastern Africa. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wondirad, A., Tolkach, D., & King, B. (2020). Stakeholder collaboration as a major factor for sustainable ecotourism development in developing countries. Tourism Management, 78, 104024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). (2019). Tourism and the sustainable development goals-journey to 2030. Available online: https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/publications/UNWTO_UNDP_Tourism%20and%20the%20SDGs.pdf (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Zolfani, S. H., Sedaghat, M., Maknoon, R., & Zavadskas, E. K. (2015). Sustainable tourism: A comprehensive literature review on frameworks and applications. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 28(1), 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žibert, M., Košcak, M., & Prevolšek, B. (2017). The importance of stakeholder involvement in strategic development of destination management: The case of the Mirna Valley destination. Academica Turistica-Tourism and Innovation Journal, 10(1), 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| SPIDER Element | Explanation | Keywords Derived |

|---|---|---|

| S-Sample | The sample focuses on stakeholders involved in sustainable destination development, such as policymakers, tourism authorities, local communities, private sector, etc. | Stakeholder collaboration, multi-stakeholder frameworks, governance structures |

| PI-Phenomenon of Interest | The study investigates multi-stakeholder frameworks and collaborative approaches used in sustainable destination development, focusing on their characteristics, functionality, and implementation. | Multi-stakeholder frameworks, sustainable tourism, destination development, operational mechanisms, collaborative approaches |

| D-Design | The research uses a comparative analysis of existing frameworks. | Contextual application, framework adaptation |

| E-Evaluation | Evaluation involves identifying implementation challenges, effectiveness, and barriers in real-world contexts, aiming to determine the practical value and adaptability of the frameworks. | Implementation challenges, stakeholder barriers, framework effectiveness, policy obstacles |

| R-Research type | The study is mostly qualitative and focuses on conceptual and contextual understanding. | Case studies, qualitative analysis |

| Category | Definition | n | % of n = 78 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conceptual models | Theoretical or/and conceptual schemes without primary application or testing | 14 | 17.9% |

| Applied case studies | Implementations in a specific destination with descriptive or/and explanatory documentation | 56 | 71.8% |

| Empirically evaluated frameworks | Explicit testing or/and evaluation of a framework using systematic data | 8 | 10.3% |

| TOTAL | 78 | 100% |

| A. | Title | Destination | Category | Focus | Methodology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F. Silva and Roque (2024) | Building the Framework for Sustainable Tourism in Príncipe Island | Príncipe Island | Applied case study | Sustainable and responsible tourism development in Príncipe for a more community-centered tourism development approach | Interviews, expert consultations, inventory and evaluation of tourist resources, four-phase plan |

| Feyers et al. (2020) | Bridging Worlds: Utilizing a Multi-Stakeholder Framework to Create Extension–Tourism Partnerships | Florida, USA | Applied case study | Building extension–tourism collaborations for responsible/eco- tourism | Nominal group meetings, questionnaires, interviews, triangulation |

| Dodds (2025) | Balancing Tourism Development and Sustainability: A Multi-Stakeholder Approach in Tofino over 15 Years | Tofino, Canada | Empirically evaluated framework | 15-year assessment of multi-stakeholder governance | Interviews, content analysis, questionnaires, triangulation |

| Salman et al. (2023) | Stakeholder management for sustainable ecotourism destinations: a case of Penang Hill Malaysia | Penang Hill, Malaysia | Empirically evaluated framework | Stakeholder management for sustainable ecotourism | Interviews, document analysis, questionnaires triangulation |

| Wondirad et al. (2024) | Tourism governance in the new normal: lessons for Eastern Africa | Eastern Africa | Conceptual model | Governance in the “new normal” for tourism | Conceptual synthesis |

| Walker (2019) | Sustainable tourism and the role of festivals in the Caribbean—case of the St. Lucia Jazz (& Arts) Festival | St. Lucia Caribbean | Conceptual model | Festivals’ role in sustainable tourism | Conceptual synthesis |

| Study | Category | Stakeholder Mapping | Stages of Involvement | Feedback Mechanisms | Inclusion of Marginalized Groups | Empirical Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wondirad et al. (2024) Eastern Africa | Conceptual model | Partial | Partial | Partial | Partial | No |

| Walker (2019) St. Lucia, Caribbean | Conceptual model | Partial | Partial | No | Partial | No |

| F. Silva and Roque (2024) Príncipe Island | Applied case study | Partial | Yes | Partial | Partial | Partial |

| Feyers et al. (2020) Florida, USA | Applied case study | Partial | Yes | Partial | Partial | Partial |

| Dodds (2025) Tofino, Canada | Empirically evaluated framework | Yes | Yes | Partial | Partial | Yes |

| Salman et al. (2023) Penang Hill, Malaysia | Empirically evaluated framework | Yes | Yes | Partial | Partial | Yes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Panagiotopoulou, P.; Skoultsos, S. Stakeholders’ Involvement in Sustainable Destination Management: A Systematic Literature Review of Existing Multi-Stakeholder Frameworks and Approaches. Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 250. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6050250

Panagiotopoulou P, Skoultsos S. Stakeholders’ Involvement in Sustainable Destination Management: A Systematic Literature Review of Existing Multi-Stakeholder Frameworks and Approaches. Tourism and Hospitality. 2025; 6(5):250. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6050250

Chicago/Turabian StylePanagiotopoulou, Polymnia, and Sofoklis Skoultsos. 2025. "Stakeholders’ Involvement in Sustainable Destination Management: A Systematic Literature Review of Existing Multi-Stakeholder Frameworks and Approaches" Tourism and Hospitality 6, no. 5: 250. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6050250

APA StylePanagiotopoulou, P., & Skoultsos, S. (2025). Stakeholders’ Involvement in Sustainable Destination Management: A Systematic Literature Review of Existing Multi-Stakeholder Frameworks and Approaches. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(5), 250. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6050250