The Fun Factor: Unlocking Place Love Through Exceptional Tourist Experiences

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Emotion in Consumer Behavior Studies

2.2. Fun

2.2.1. Definitions

2.2.2. Dimensions of Fun

2.3. Hypotheses Development

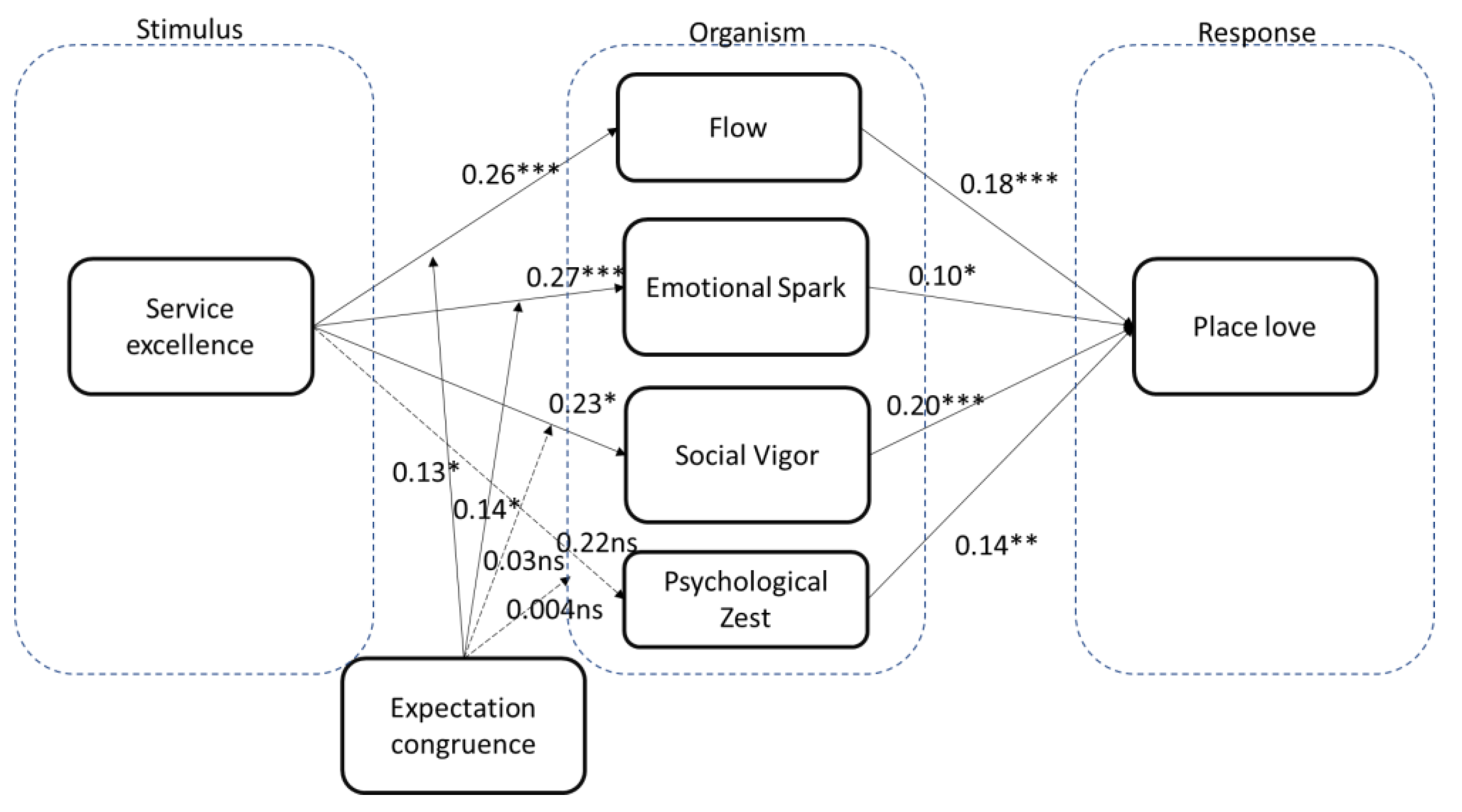

2.3.1. Effect of Service Excellence (S) on Fun (O)

2.3.2. Effect of Fun (O) on Place Love (R)

2.3.3. Expectation Congruence as a Moderator

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Collection and Sample

3.2. Survey Instrument

3.3. Socio-Demographic and Trip Characteristics Information

4. Results

4.1. Face and Content Validity

4.2. Construct Validity

4.3. Predictive Validity

4.3.1. CFA

4.3.2. SEM

4.3.3. The Moderating Effect of Expectation Congruence

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Study Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Andersen, M. K., & Ankerstjerne, P. (2013). Service management 2.0—The next generation of service. ISS White Paper. IFMA. Available online: https://otcc.sharepoint.com/Documents/Service_Management_30.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2022).

- Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M., & Gouthier, M. H. (2014). What service excellence can learn from business excellence models. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 25(5–6), 511–531. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R. P. (1986). Principles of marketing management. Science Research Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Beaton, D. E., Bombardier, C., Guillemin, F., & Ferraz, M. B. (2000). Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine, 25(24), 3186–3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bose, S., Pradhan, S., Bashir, M., & Roy, S. K. (2022). Customer-based place brand equity and tourism: A regional identity perspective. Journal of Travel Research, 61(3), 511–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R. W. (1970). Back-translation for cross-cultural research. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 1(3), 185–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B. M. (2016). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming (3rd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, B. A., & Ahuvia, A. C. (2006). Some antecedents and outcomes of brand love. Marketing Letters, 17(2), 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X., Cheng, Z. F., & Kim, G. B. (2020). Make it memorable: Tourism experience, fun, recommendation, and revisit intentions of Chinese outbound tourists. Sustainability, 12(5), 1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X., Wen, B., & Wu, Z. (2021). An empirical study of workplace attachment in tourism scenic areas: The positive effect of workplace fun on voluntary retention. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 26(5), 579–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H., & Choi, H. C. (2019). Investigating tourists’ fun-eliciting process toward tourism destination sites: An application of cognitive appraisal theory. Journal of Travel Research, 58(5), 732–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, S. L., Angello, G., Saenz, M., & Quek, F. (2017). Fun in Making: Understanding the experience of fun and learning through curriculum-based Making in the elementary school classroom. Entertainment Computing, 18, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1975). Play and intrinsic rewards. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 15(3), 41–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. Harper & Row. [Google Scholar]

- De Clercq, D., Bouckenooghe, D., Raja, U., & Matsyborska, G. (2014). Unpacking the goal congruence–organizational deviance relationship: The roles of work engagement and emotional intelligence. Journal of Business Ethics, 124, 695–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMatos, N. M., De Sa, E. S., & De Oliveira Duarte, P. A. (2021). A review and extension of the flow experience concept. Insights and directions for tourism research. Tourism Management Perspectives, 38, 100802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, G., Skrocki, A., Goebel, D., Janes, K., Locke, D., Catalan, E., & Zanolini, W. (2024). Youth development travel programs: Facilitating engagement, deep experience, and “sparks” through self-relevance and stories. Journal of Leisure Research, 55(5), 621–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2022). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (3rd ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S., Yoon, J., & Kwon, J. (2021). Impact of experiential value of augmented reality: The context of heritage tourism. Sustainability, 13, 4147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2022). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Holbrook, M. B., & Hirschman, E. C. (1982). The experiential aspects of consumption: Consumer fantasies, feelings, and fun. Journal of Consumer Research, 9(2), 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosany, S., Sthapit, E., & Björk, P. (2022). Memorable tourism experience: A review and research agenda. Psychology & Marketing, 39(8), 1467–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J., Ellis, G. D., Ettekal, A. V., & Nelson, C. (2022). Situational engagement experiences: Measurement options and theory testing. Journal of Business Research, 150, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D., Fredrickson, B. L., Schreiber, C. A., & Redelmeier, D. A. (1993). When more pain is preferred to less: Adding a better end. Psychological Science, 4(6), 401–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J., Jin, B., & Gavin, M. (2010). The positive emotion elicitation process of Chinese consumers towards a U.S. apparel brand—A cognitive appraisal perspective. Journal of the Korean Society of Clothing and Textiles, 34(12), 1992–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitayama, S., Mesquita, B., & Karasawa, M. (2006). Cultural affordances and emotional experience. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91(5), 890–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. (2023). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (5th ed.). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kusuma, I. G. A. E. T., Yasmari, N. N. W., Agung, A. A. P., & Landra, N. (2021). When satisfaction is not enough to build a word of mouth and repurchase intention. Asia Pacific Management and Business Application, 10(1), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landis, R. S., Beal, D. J., & Tesluk, P. E. (2000). A comparison of approaches to forming composite measures in structural equation models. Organizational Research Methods, 3(2), 186–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockstone, L., & Baum, T. (2008). Fun in the family: Tourism and the commonwealth games. International Journal of Tourism Research, 10(6), 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maisam, S., & Mahsa, R. D. (2016). Positive word of mouth marketing: Explaining the roles of value congruity and brand love. Journal of Competitiveness, 8(1), 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathwick, C., Malhotra, N., & Rigdon, E. (2001). Experiential value: Conceptualization, measurement and application in the catalog and Internet shopping environment. Journal of Retailing, 77(1), 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, A., & Russell, J. A. (1974). An approach to environmental psychology. MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura, J., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2009). Flow theory and research. Handbook of Positive Psychology, 195, 206. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, T. D., & Peterson, E. W. (2009). Stemming the tide of law student depression: What law schools need to learn from the science of positive psychology. GW Law Faculty Publications & Other Works, 9, 357. [Google Scholar]

- Pham, M. T., Hung, I. W., & Gorn, G. J. (2011). Relaxation increases monetary valuations. Journal of Marketing Research, 48(5), 814–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponsignon, F., Jaud, D. A., Durrieu, F., & Lunardo, R. (2024). The ability of experience design characteristics to elicit epistemic value, hedonic value, and visitor satisfaction in a wine museum. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 36(8), 2582–2600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roseman, C. C. (1983). A framework for the study of migration destination selection. Population and Environment, 6(3), 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Frederick, C. (1997). On energy, personality, and health: Subjective vitality as a dynamic reflection of well-being. Journal of Personality, 65(3), 529–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, A., & Sarkar, J. G. (2021). Managing customers’ undesirable responses towards hospitality service brands during service failure: The moderating role of other customer perception. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 94, 02873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sezgin, F., & Erdogan, O. (2015). Academic optimism, hope and zest for work as predictors of teacher self-efficacy and perceived success. Educational Science Theory & Practice, 15(1), 7–19. [Google Scholar]

- Shafiee, M. M., Foroudi, P., & Tabaeeian, R. A. (2021). Memorable experience, tourist destination identification and destination love. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 7(3), 799–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sihombing, S. O., Antonio, F., Sijabat, R., & Bernarto, I. (2024). The role of tourist experience in shaping memorable tourism experiences and behavioral intentions. International Journal of Sustainable Development & Planning, 19(4), 1314. [Google Scholar]

- Sin, L., Cheung, G. W., & Lee, R. (1999). Methodology in cross-cultural consumer research and critical assessment. Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 11(4), 75–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C. A., & Ellsworth, P. C. (1985). Patterns of cognitive appraisal in emotion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48(4), 813–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sternberg, R. J. (1986). A triangular theory of love. Psychological Review, 93(2), 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, K. (2015). Place brand love and marketing to place consumers as tourists. Journal of Place Management and Development, 8(2), 142–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talarico, J. M., LaBar, K. S., & Rubin, D. C. (2004). Emotional intensity predicts autobiographical memory experience. Memory & Cognition, 32(7), 1118–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tasci, A. D., & Ko, Y. J. (2015). A fun-scale for understanding the hedonic value of a product: The destination context. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 33(2), 162–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, J. L. (2007). Ideal affect. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 2(3), 242–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vieira, L. C., & da Silva, F. S. C. (2017). Assessment of fun in interactive systems: A survey. Cognitive Systems Research, 41, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viglia, G., & Dolnicar, S. (2020). A review of experiments in tourism and hospitality. Annals of Tourism Research, 80, 102858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilk, R. (2022). Taking fun seriously in envisioning sustainable consumption. Consumption and Society, 1(2), 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worthington, R. L., & Whittaker, T. A. (2006). Scale development research: A content analysis and recommendations for best practices. The Counseling Psychologist, 34(6), 806–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, L. H. V., Tisdall, K., & Moore, N. (2021). Taking emotions seriously: Fun and pride in participatory research. Emotion, Space and Society, 41, 100836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factor (Cronbach’s α) | Standardized Loading | t-Statistic | Construct Reliability | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stimulus—Service Excellence (0.766) | 0.782 | 0.549 | ||

| When I thought of this place, I thought of excellence. | 0.672 | |||

| I thought this place provided expert service. | 0.883 | 13.503 | ||

| The service in this place was attentive. | 0.645 | 11.489 | ||

| Organism—Fun | ||||

| Social vigor (0.824) | 0.827 | 0.615 | ||

| This place offered me surprising experiences. | 0.737 | |||

| Experiencing this place made me feel energized. | 0.820 | 15.867 | ||

| This place made me feel social. | 0.794 | 15.425 | ||

| Psychological zest (0.812) | 0.812 | 0.684 | ||

| My visit to this place made me enjoyable. | 0.808 | |||

| My visit to this place gave me excitement. | 0.846 | 16.769 | ||

| Emotion spark (0.865) | 0.887 | 0.724 | ||

| My visit to this place provided emotional peaks. | 0.877 | |||

| My visit to this place made me feel emotionally involved. | 0.832 | 19.732 | ||

| My visit to this place made me feel emotionally charged. | 0.844 | 18.031 | ||

| Flow (0.887) | 0.883 | 0.655 | ||

| My visit to this place made me forget about my daily routine. | 0.735 | |||

| My visit to this place helped me forget about time. | 0.728 | 17.625 | ||

| My visit to this place helped me forget about my social status. | 0.902 | 18.130 | ||

| My visit to this place helped me forget about other places. | 0.859 | 17.421 | ||

| Response—Place Love (0.876) | 0.868 | 0.524 | ||

| This place was wonderful. | 0.761 | |||

| This place made me feel good. | 0.714 | 17.394 | ||

| This place was awesome. | 0.790 | 15.384 | ||

| I loved this place. | 0.707 | 14.173 | ||

| I was passionate about this place. | 0.667 | 12.816 | ||

| I was attached to this place. | 0.698 | 13.470 | ||

| Expectation congruence (0.867) | 0.919 | 0.791 | ||

| The place’s reputation was well matched. | 0.905 | |||

| This place’s image was well matched. | 0.923 | 18.324 | ||

| This place’s location was well placed. | 0.838 | 17.325 |

| Path | Standardized Estimate | t-Statistic | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social vigor ← Service excellence | 0.56 | 11.60 *** | Supported (+) |

| Psychological zest ← Service excellence | 0.46 | 10.27 *** | Supported (+) |

| Emotional Spark ← Service excellence | 0.66 | 12.21 *** | Supported (+) |

| Flow ← Service excellence | 0.58 | 10.82 *** | Supported (+) |

| Place love ← Social vigor | 0.20 | 4.32 *** | Supported (+) |

| Place love ← Psychological zest | 0.14 | 2.61 *** | Supported (+) |

| Place love ← Emotional Spark | 0.10 | 2.11 * | Supported (+) |

| Place love ← Flow | 0.18 | 4.06 *** | Supported (+) |

| X = Service Excellence | Bias-Corrected Bootstrap 95% CI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mediator (M) | Moderator (W) | Indirect Effect | Boot SE | LL | UL |

| Flow | EC Low | 0.043 | 0.018 | 0.014 | 0.082 |

| EC High | 0.082 | 0.024 | 0.040 | 0.131 | |

| Emotional Spark | EC Low | 0.036 | 0.019 | 0.001 | 0.077 |

| EC High | 0.059 | 0.028 | 0.003 | 0.111 | |

| Social Vigor | EC Low | 0.082 | 0.024 | 0.040 | 0.135 |

| EC High | 0.072 | 0.023 | 0.032 | 0.120 | |

| Psychological Zest | EC Low | 0.045 | 0.018 | 0.011 | 0.082 |

| EC High | 0.044 | 0.019 | 0.010 | 0.082 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Choi, H.; Choi, H.C.; Liang, L.J. The Fun Factor: Unlocking Place Love Through Exceptional Tourist Experiences. Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 246. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6050246

Choi H, Choi HC, Liang LJ. The Fun Factor: Unlocking Place Love Through Exceptional Tourist Experiences. Tourism and Hospitality. 2025; 6(5):246. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6050246

Chicago/Turabian StyleChoi, Hyeyoon, Hwansuk Chris Choi, and Lena Jingen Liang. 2025. "The Fun Factor: Unlocking Place Love Through Exceptional Tourist Experiences" Tourism and Hospitality 6, no. 5: 246. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6050246

APA StyleChoi, H., Choi, H. C., & Liang, L. J. (2025). The Fun Factor: Unlocking Place Love Through Exceptional Tourist Experiences. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(5), 246. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6050246