Fostering Visitor Engagement Through Serious Game-Based Mediation in Small Local Museums

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Museums, Generation Z, and Serious Games

2.2. Museums as Interpreters of Heritage Values

2.3. NaMuenSri Museum: A Case Study of a Thai Traditional Textile Museum

3. Research Methods

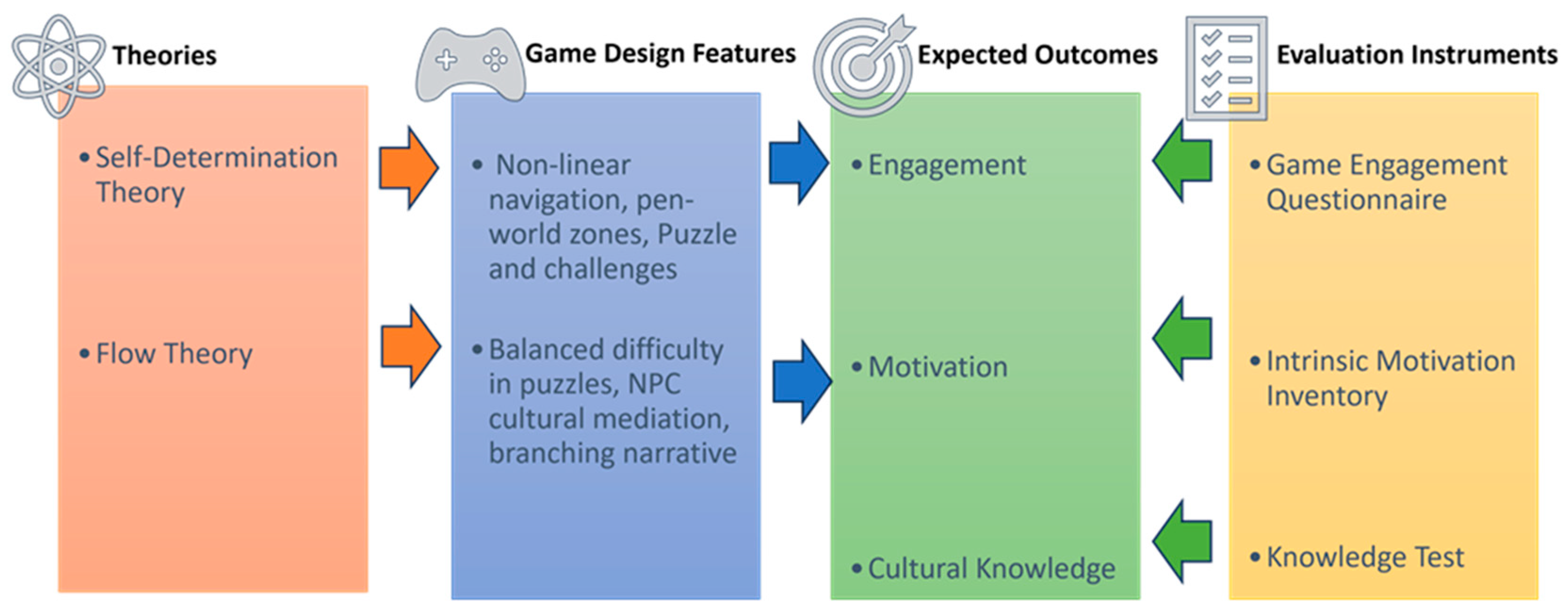

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Participants and Sampling Strategy

3.3. Research Instruments

3.4. Data Collection and Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Overview of Game Development

4.2. Key Features and Functionalities

5. Evaluation

5.1. Demographic and Gameplay Background

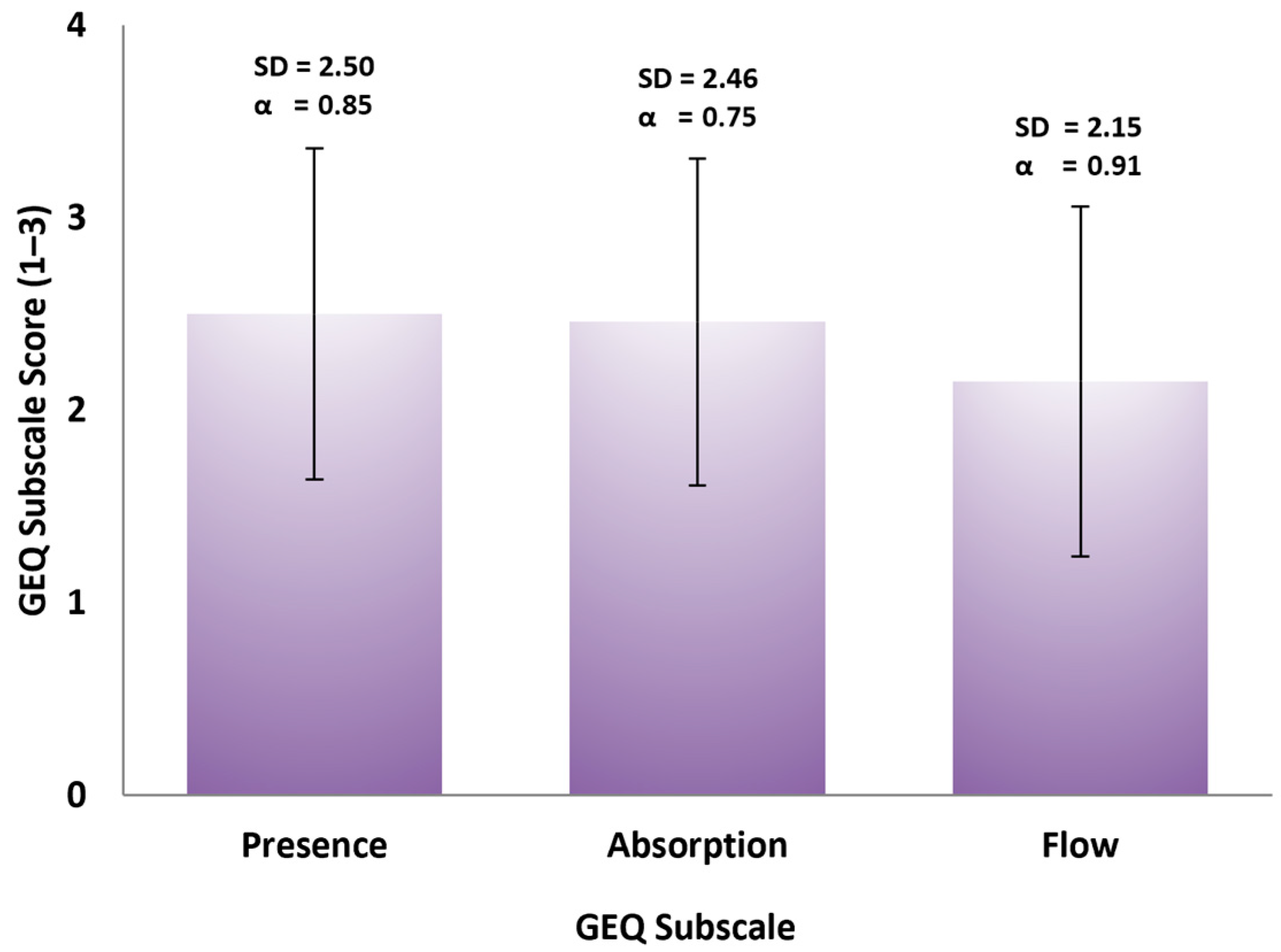

5.2. Game Engagement

5.3. Intrinsic Motivation

5.4. Knowledge Outcomes Assessment

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Black, G. (2020). Museums and the challenge of change: Old institutions in a new world. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, S. J., Rowling, H. C., & Kirk, D. (2025). Story inspiration station: Deeper engagement with museum objects via participatory interpretation. Journal on Computing and Cultural Heritage. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockmyer, J. H., Fox, C. M., Curtiss, K. A., McBroom, E., Burkhart, K. M., & Pidruzny, J. N. (2009). The development of the game engagement questionnaire: A measure of engagement in video game-playing. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45(4), 624–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K., & Mairesse, F. (2018). The definition of the museum through its social role. Curator: The Museum Journal, 61(4), 525–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvi, L., & Vermeeren, A. P. O. S. (2024). Small museums designing new visitor experiences: Needs, limitations and opportunities. Museums & Social Issues, 18(1–2), 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, R. (2021). Museums, tourism and interpretation of the heritage. Revista Rosa Dos Ventos—Turismo e Hospitalidade, 13(3), 894–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camuñas-García, D., Cáceres-Reche, M. P., de la Cambil-Hernández, M. E., & Lorenzo-Martín, M. E. (2024). Digital game-based heritage education: Analyzing the potential of heritage-based video games. Education Sciences, 14(4), 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carfora, N., Ferguson, B., Bailey, L., Gwilt, I., & Alford, K. (2024). A participatory approach to exhibition theme development. Museum Management and Curatorship, 1(18), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caserman, P., Hoffmann, K., Müller, P., Schaub, M., Straßburg, K., Wiemeyer, J., Bruder, R., & Göbel, S. (2020). Quality criteria for serious games: Serious part, game part, and balance. JMIR Serious Games, 8(3), e19037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai-Arayalert, S., Puttinaovarat, S., & Saetang, W. (2024). Chatbot-mediated technology to enhance experiences in historical textile museums. Cogent Arts & Humanities, 11(1), 2396206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai-Arayalert, S., Puttinaovarat, S., & Saetang, W. (2025). Phygital Experience platform for textile exhibitions in small local museums. Heritage, 8(1), 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai-Arayalert, S., Suttapong, K., & Kong-Rithi, W. (2021). Systematic approach to preservation of cultural handicrafts: Case study on fabrics hand-woven in Thailand. Cogent Business & Management, 8(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Checa, D., & Bustillo, A. (2020). A review of immersive virtual reality serious games to enhance learning and training. Multimedia Tools and Applications, 79(9–10), 5501–5527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chumduang, W., & Thirathamrongwee, P. (2025). Sustaining a local museum by creating value through a museum teamwork network: A case study of Si Sutthawat temple museum, Thailand. MANUSYA: Journal of Humanities, 28(1), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, A. (2025). In real life: Gaming community engagement in museums. Curator: The Museum Journal, 68(1), 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordova-Rangel, J., & Caro, K. (2023). Designing and evaluating Aventura marina: A Serious game to promote visitors’ engagement in a science museum exhibition. Interacting with Computers, 35(2), 387–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. Harper and Row. [Google Scholar]

- Ćosović, M., & Brkić, B. R. (2019). Game-based learning in museums—Cultural heritage applications. Information, 11(1), 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DaCosta, B., & Kinsell, C. (2022). Serious games in cultural heritage: A review of practices and considerations in the design of location-based games. Education Sciences, 13(1), 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergin, G. (2024). Bridging the gap: Using digital interactives for social museums. Yedi, Sanatta Dijitalizm Özel Sayısı, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer-Yulfo, A. (2022). Transforming museum education through intangible cultural heritage. Journal of Museum Education, 47(3), 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannini, T., & Bowen, J. P. (2022). Museums and digital culture: From reality to digitality in the age of COVID-19. Heritage, 5(1), 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hester, E., Geegan, S., & Parker, K. A. (2022). Learning “through the Prism of Art”: Engaging Gen Z students with university art museums. The International Journal of Learning in Higher Education, 29(1), 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X., Li, Y., & Tian, F. (2025). Enhancing user experience in interactive virtual museums for cultural heritage learning through extended reality: The case of Sanxingdui bronzes. IEEE Access, 13, 59405–59421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnchanaporn, N., & Lumthaweepaisal, C. (2023). Spatial Dialogues between Exhibited Interiors and Cultural Exteriors: How Local Museums Connect to the Community. Interiority, 6(1), 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, D. A., Boyatzis, R. E., & Mainemelis, C. (2014). Experiential learning theory: Previous research and new directions. In Perspectives on thinking, learning, and cognitive styles (pp. 227–248). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H., & Zhang, M. (2025). Museum game-based learning: Innovative approaches from a constructivist perspective. Frontiers in Education, 10, 1576207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Zheng, X., Watanabe, I., & Ochiai, Y. (2024). A systematic review of digital transformation technologies in museum exhibition. Computers in Human Behavior, 161, 108407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L., Hew, K. F., & Du, J. (2024). Gamification enhances student intrinsic motivation, perceptions of autonomy and relatedness, but minimal impact on competency: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Educational Technology Research and Development, 72(2), 765–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, Y., & Xie, J. (2024). The evolution of digital cultural heritage research: Identifying key trends, hotspots, and challenges through bibliometric analysis. Sustainability, 16(16), 7125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lushnikova, A., Morse, C., Doublet, S., Koenig, V., & Bongard-Blanchy, K. (2023). Self-determination theory applied to museum website experiences: Fulfill visitor needs, increase motivation, and promote engagement. Proceedings of the European Conference on Cognitive Ergonomics 2023, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, C. G., Pedro, J. P., & Araújo, I. (2023). A systematic literature review of gamification in/for cultural heritage: Leveling up, going beyond. Heritage, 6(8), 5935–5951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moller, A. C., Kornfield, R., & Lu, A. S. (2024). Competition and digital game design: A self-determination theory perspective. Interacting with Computers, iwae023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moneta, A., Hodgson, N., & Fearon, E. (2025). Re-interpreting intangible cultural heritage through immersive live performances to enhance memory-based institutions and foster community engagement. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 31(5), 640–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neather, R. (2024). Translating for museums, galleries and heritage sites. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Nowacki, M. (2021). Heritage interpretation and sustainable development: A systematic literature review. Sustainability, 13(8), 4383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, W., Hamari, J., Joaquim, S., Toda, A. M., Palomino, P. T., Vassileva, J., & Isotani, S. (2022). The effects of personalized gamification on students’ flow experience, motivation, and enjoyment. Smart Learning Environments, 9(1), 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, G., & Zonah, S. (2025). Revolutionising heritage interpretation with smart technologies: A blueprint for sustainable tourism. Sustainability, 17(10), 4330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pentescu, A. (2023). Cultural heritage and new technologies: Exploring opportunities for cultural heritage sites from Gen Z’s perspective. Studies in Business and Economics, 18(3), 230–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashed, A., Shirmohammadi, S., Amer, I., & Hefeeda, M. (2025). A review of player engagement estimation in video games: Challenges and opportunities. ACM Transactions on Multimedia Computing, Communications and Applications, 21(7), 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvic, S., Boskovic, D., Okanovic, V., Sljivo, S., & Zukic, M. (2019). Interactive digital storytelling: Bringing cultural heritage in a classroom. Journal of Computers in Education, 6(1), 143–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robaina-Calderín, L., Martín-Santana, J. D., & Muñoz-Leiva, F. (2023). Immersive experiences as a resource for promoting museum tourism in the Z and millennials generations. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 29(1), 100795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosser, P., & Soler, S. (2024). Heritage education of memory: Gamification to raise awareness of the cultural heritage of war. Heritage, 7(8), 3960–3996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Rigby, C. S. (2020). Motivational foundations of game-based learning. In J. L. Pass, R. E. Mayer, & B. D. Homer (Eds.), Handbook of game-based learning (pp. 153–176). The MIT Press Cambridge. [Google Scholar]

- Saxena, M., & Mishra, D. K. (2021). Gamification and Gen Z in higher education. International Journal of Information and Communication Technology Education, 17(4), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirivanichkul, J., Noobanjong, K., Saengratwatchara, S., Damrongsakul, W., & Louhapensang, C. (2018). Interpretation of a local museum in Thailand. Sustainability, 10(7), 2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taormina, F., & Baraldi, S. B. (2022). Museums and digital technology: A literature review on organizational issues. European Planning Studies, 30(9), 1676–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, K., King, V., & Chan, K. (2021). Examining essential flow antecedents to promote students’ self-regulated learning and acceptance of use in a game-based learning classroom. Electronic Journal of E-Learning, 19(6), 531–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N., Jia, C., Wang, J., & Li, Z. (2025). Identifying key factors influencing immersive experiences in virtual reality enhanced museums. Scientific Reports, 15(1), 31990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weng, L., Liang, Z., & Bao, J. (2020). The effect of tour interpretation on perceived heritage values: A comparison of tourists with and without tour guiding interpretation at a heritage destination. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 16, 100431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y., Liu, S., & Song, X. (2023). The co-creation of museum experience value from the perspective of visitor motivation. Sage Open, 13(4), 21582440231202120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Category | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 46.7% |

| Female | 53.3% | |

| Age Range | 18–21 years | 60.0% |

| 22–25 years | 40.0% | |

| Gameplay Frequency | Daily | 33.3% |

| Weekly | 50.0% | |

| Occasionally (monthly) | 16.7% | |

| Preferred Platform | Mobile | 66.7% |

| PC | 23.3% | |

| Console | 10.0% | |

| Experience with Digital or Computer Games | Yes | 30.0% |

| No | 70.0% | |

| Average Gameplay Hours (per week) | 1–4 h | 30.0 |

| 5–7 h | 43.3 | |

| 8+ h | 26.7 | |

| Preferred Game Genres | Casual/Puzzle | 46.7 |

| Role-Playing (RPG) | 26.7 | |

| Simulation/Strategy | 16.7 | |

| Others (Sports/Action) | 10.0 | |

| Experience with Serious/Educational Games | Yes | 20.0 |

| No | 80.0 | |

| Gameplay Context | Mostly single-player | 63.3 |

| Single and multiplayer | 36.7 |

| Subscale | No. of Items | Means 1 | SD | Cronbach’s α 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absorption | 7 | 2.46 | 0.25 | 0.85 |

| Flow | 9 | 2.15 | 0.10 | 0.91 |

| Presence | 4 | 2.50 | 0.06 | 0.86 |

| Overall | 19 | 2.32 | 0.76 | 0.83 |

| Subscale | No. of Items | M 1 | SD | Cronbach’s α 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interest/Enjoyment | 4 | 4.93 | 1.70 | 0.84 |

| Perceived Competence | 4 | 5.73 | 1.73 | 0.71 |

| Effort/Importance | 3 | 4.34 | 1.38 | 0.75 |

| Value/Usefulness | 3 | 4.99 | 1.30 | 0.75 |

| Overall | 14 | 5.05 | 1.64 | 0.92 |

| Test | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-test | 4.40 | 2.13 |

| Post-test | 8.03 | 1.35 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chai-Arayalert, S.; Puttinaovarat, S. Fostering Visitor Engagement Through Serious Game-Based Mediation in Small Local Museums. Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 218. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6040218

Chai-Arayalert S, Puttinaovarat S. Fostering Visitor Engagement Through Serious Game-Based Mediation in Small Local Museums. Tourism and Hospitality. 2025; 6(4):218. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6040218

Chicago/Turabian StyleChai-Arayalert, Supaporn, and Supattra Puttinaovarat. 2025. "Fostering Visitor Engagement Through Serious Game-Based Mediation in Small Local Museums" Tourism and Hospitality 6, no. 4: 218. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6040218

APA StyleChai-Arayalert, S., & Puttinaovarat, S. (2025). Fostering Visitor Engagement Through Serious Game-Based Mediation in Small Local Museums. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(4), 218. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6040218