Abstract

Community-based tourism (CBT) is deemed a powerful means for enhancing community well-being and ethnic cultural preservation (CP). However, its sustainability has been challenged by resource scarcity, environmental pollution and funding instability in Vietnam. This study investigates young tourists’ perceptions of and financial contributions to community-based tourism associated with cultural preservation (CBT-CP) at Lac Village, a key White Thai ethnic site in Phu Tho province. Specifically, the contingent valuation method (CVM) coupled with an interval regression model was used to analyze the data obtained from 275 respondents during December 2024 to estimate the willingness to pay (WTP) for CBT-CP and identify influencing factors. We found that nearly 50% of the respondents are willing to contribute financially, with an average of roughly USD 4.45 per visit. This leads to total contributions of USD 2413 for all respondents and USD 1541 for respondents with a high certainty level of commitment. Additionally, we found that key barriers to WTP for CBT-CP are fiscal transparency concerns, personal financial limitations, and individual determinants. These findings offer many policy implications for mobilizing young tourists’ untapped funding, strengthening local management capacity, and advocating for enhanced transparency to improve CBT-CP in the study area and beyond.

1. Introduction

Community-based tourism (CBT) is deemed a strategic vehicle for sustainable development in regions endowed with rich cultural and ecological assets. By vesting tourism governance in local communities, CBT can promote inclusive economic growth, reinforces environmental stewardship, and preserve intangible cultural heritage (Ngo et al., 2024; Zabeen et al., 2023). Notably, Vietnam is a country where ethnic minorities predominantly inhabit mountainous rural areas, so CBT offers particular potential to enhance livelihoods, safeguard traditional practices, and protect fragile ecosystems. Importantly, this approach is codified in national policy, Decision No. 1719/QĐ–TTg, which establishes the 2021–2030 Target Program for socio-economic development in ethnic minority and mountainous regions.

Lac Village, located in Mai Chau ward, Phu Tho province, exemplifies a pioneering CBT model in northern Vietnam, blending cultural authenticity and natural beauty through White Thai traditions such as stilt house architecture, brocade weaving, and folk dance. Most households engage in tourism services, ensuring broad-based economic participation and supporting Vietnam’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). However, Lac Village also faces a growing set of challenges. Recent studies and local reports have noted that peak weekend visitor numbers frequently exceed the village’s environmental carrying capacity, placing pressure on waste management infrastructure and water resources (Truong, 2020), market standardization following the COVID-19 shift toward domestic tourism, and uneven growth among its five hamlets that leads to disparities in service quality and heritage conservation (T. H. Tran et al., 2018; Truong, 2020). These issues underscore the urgent need to enhance and adapt Lac Village’s CBT model to ensure long-term sustainability and cultural integrity.

Since its inception as a participatory model in the early 2000s (Denman, 2001), CBT research has emphasized inclusive economic growth, environmental stewardship, and cultural preservation (Dodds et al., 2018; Oka et al., 2021). Recently, scholarly attention has turned to youth engagement as a pivotal catalyst for CBT innovation: younger generations are co-designing immersive homestays, leveraging digital storytelling to interpret heritage, and leading eco-education and cultural workshops that deepen local identity and visitor engagement (Oltean et al., 2025; Stanciu et al., 2022). In Vietnam, young people’s digital fluency, social networks, and entrepreneurial drive position them to enhance heritage interpretation and destination marketing.

Despite extensive analysis of community-based tourism through institutional, service-quality, and visitor-satisfaction lenses, empirical exploration of tourists’ economic behavior—particularly their willingness to pay for cultural heritage conservation and service enhancements—remains scarce. Notably, no study has applied the contingent valuation method to estimate tourists’ willingness to pay for service enhancement or heritage conservation in Lac Village, and the role of youth in CBT development is still underexplored. These limitations underscore the need for an in-depth study that integrates econometric tools and generational perspectives to assess both the potential and challenges of CBT in Lac Village, considering its current development trajectory.

This study addresses three questions: (1) How do young visitors perceive key CBT elements in Lac Village? (2) To what extent are they willing to financially support CBT linked to cultural preservation? (3) Which service attributes influence satisfaction and WTP? Accordingly, the study aims to assess young tourists’ perceptions and WTP for CBT integrated with cultural heritage preservation and to propose the establishment of a Community Cultural Preservation and Tourism Development Fund as a mechanism to channel contributions toward maintaining the cultural identity of the Thai ethnic group and enhancing service quality. Additionally, the research investigates youth awareness and concern regarding various dimensions of CBT such as accommodation, cuisine, environmental landscape, and cultural experience. Furthermore, our study estimates tourists’ willingness to pay for the fund using the contingent valuation method (CVM) and identifies service attributes that influence satisfaction and behavioral intention. By doing so, this study advances the literature and practice of CBT–CP in ethnic minority areas of Vietnam through four interrelated contributions. First, it reveals how young tourists value and prioritize cultural authenticity, cuisine, environmental quality, and service delivery, offering guidance for experience redesign. Second, by applying the contingent valuation method, it provides the first economic estimate of tourists’ WTP for cultural preservation in Lac Village. Third, it identifies service satisfaction gaps to inform targeted improvements and more equitable planning. Finally, it links financial intention with cultural engagement, supplying policy insights that align heritage protection with youth participation and destination branding.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis

2.1. Community-Based Tourism

Community-based tourism (CBT) is a participatory form of tourism in which local communities take the lead in planning and managing activities, with most benefits retained within the community (Denman, 2001). As a sustainable alternative to mass tourism, CBT promotes economic growth, cultural preservation, and environment stewardship but also faces governance and resource constraints that limit participation (Jamal & Getz, 1995; Anindhita et al., 2024; Xu et al., 2019). Beyond its economic role, community-based tourism (CBT) fosters cultural sustainability by enabling communities to preserve and transmit traditions, reinforcing cultural pride and collective identity (Jackson, 2025). Authentic resident visitor exchanges further strengthen mutual understanding and the long-term resilience of cultural heritage (Herranz et al., 2004).

To capture the value of these cultural and environmental benefits, willingness to pay (WTP) is widely employed as a measure of the non-market value of tourism services and cultural resources. WTP reflects the maximum amount individuals are willing to pay for perceived improvements and is shaped by both psychological and contextual factors (Gall-Ely, 2009). Empirical research has shown that WTP is influenced by environmental awareness, income, and perceptions of quality enhancement (Ma et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2025). In Vietnam, for example, a study in Hanoi estimated household WTP for air quality improvement at 70,935 VND/month, with education and age as significant predictors. Notably, 46.5% of respondents unwilling to pay cited lack of trust in fund effectiveness as the main reason (Q. N. Nguyen et al., 2024). Methodologically, WTP is typically assessed through contingent valuation, auction experiments, or conjoint analysis, each offering different advantages in validity and applicability (Gall-Ely, 2009).

In recent years, youth engagement has emerged as a critical dimension of CBT. Younger travelers increasingly seek authentic and immersive cultural experiences (Boukas, 2008; Stanciu et al., 2022). Their digital fluency and extensive social networks allow them to co-design tourism products, amplify community narratives, and inspire broader participation. Importantly, young people’s strong appreciation for cultural heritage and growing sense of national identity and pride motivate them to actively support initiatives that safeguard traditions (Oltean et al., 2025; Lim et al., 2023). By engaging youth, CBT initiatives not only attract a dynamic visitor group but also ensure that cultural values are transmitted and renewed across generations.

Within Vietnam, domestic scholarship increasingly positions CBT as a strategic driver of sustainable rural development, contributing to economic diversification, cultural revitalization, and improved local livelihoods (N. T. T. Vu & Dang, 2023). Empirical evidence highlights that CBT activities such as homestays, community-operated food services, local guiding, and traditional handicrafts both generate employment and safeguard cultural heritage (Dao & Vu, 2018). V. C. Vu (2014) further underscores the role of CBT in environmental protection and cultural revitalization while T. T. Tran and Ta (2021) emphasize the capacity of communities to leverage endogenous resources for inclusive growth and long-term resilience.

However, despite extensive research on CBT in Vietnam and worldwide, existing studies largely focus on overall impacts, governance, or development models. Much less attention has been paid to the perceptions and roles of young tourists. In particular, how young visitors engage with and evaluate accommodation, cuisine, landscapes, and cultural activities in CBT contexts remains underexplored. Given their love of culture, openness to new experiences, and sense of national pride, young tourists are not only consumers of CBT services but also active agents in disseminating cultural values and strengthening the identity of ethnic minority communities. This study addresses that gap by applying the contingent valuation method (CVM) to assess young visitors’ WTP for preserving Thai ethnic cultural identity and enhancing local CBT services in Lac Village. By doing so, it provides an evidence-based foundation for building a sustainable CBT model that integrates cultural preservation with national development goals, while harnessing the potential of youth as cultural ambassadors and drivers of long-term resilience.

2.2. Hypothesis

Demographic and socio-economic characteristics are pivotal determinants of tourists’ willingness to pay (WTP), shaping both financial capacity and psychological engagement with community-based tourism (CBT). Gender differences influence sustainable consumption, with women more likely to endorse environmental expenditures such as green taxes (Ortega-Rodríguez et al., 2024). Financial status also plays a central role, as higher income aligns with stronger non-use values and greater capacity to pay for environmentally responsible services (Ondieki et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2025; Shen et al., 2023). In addition, birthplace, cultural identity, and local values can heighten place attachment and communal obligation, thereby increasing WTP (Ma et al., 2021; Ezeh & Dube, 2024). Travel frequency further moderates these relationships: frequent travelers may compare destinations and feel less urgency to contribute, whereas infrequent travelers often experience greater novelty and attachment, reinforcing financial support. Drawing on this synthesis, we propose the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 1.

Demographic and socio-economic characteristics (gender, financial status, birthplace, and travel frequency) are significantly associated with tourists’ WTP for CBT-CP.

Accommodation convenience and reasonable living costs shape tourists’ WTP by enhancing both experiential efficiency and perceived value. Convenient location improves access and trip efficiency, while prices aligned with travelers’ reference points strengthen fairness perceptions (Boronat-Navarro & Pérez-Aranda, 2020; García et al., 2017). Moreover, reasonable living costs, when connected to tangible benefits such as sustainable practices or superior facilities, enhance perceived fairness and reinforce WTP (Nelson et al., 2021; Musa & Nadarajah, 2023; de Araújo et al., 2022). Clean, well-equipped accommodation and diverse facilities further differentiate destinations and elevate value perceptions (Masiero et al., 2015). Building on these insights, we propose the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 2.

Positive perceptions of accommodation convenience and reasonable living costs positively influence WTP for CBT-CP.

Local cuisine and cultural experiences exert a stronger influence on WTP than functional service attributes because they fulfill deeper needs for authenticity and identity. Authentic cultural interactions foster place attachment and a sense of moral responsibility to sustain traditions, which elevate perceived experiential value and payment intentions (Uslu et al., 2023; Zhao & Chan, 2023; Báez-Montenegro et al., 2012). Similarly, high-quality, culturally distinctive cuisine strengthens emotional ties and destination loyalty, while sustainable dining practices heighten concern for cultural continuity by reinforcing responsibility to preserve local traditions (de Farias et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2019). Accordingly, we propose the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 3.

Positive perceptions of local cuisine and cultural experiences positively influence WTP for CBT-CP.

Perceived environmental cleanliness and high environmental quality strongly shape destination image, emotional connection, and ethical motivations, thereby influencing WTP. Clean and aesthetically pleasing landscapes enhance perceived value and inspire financial support for conservation initiatives (Wang et al., 2025; Shen et al., 2023). Evidence from coastal and ecotourism contexts shows that reducing plastic pollution and offering plastic-free experiences significantly raise WTP, underscoring the economic value visitors place on environmental quality (Panwanitdumrong & Chen, 2022; Mutuku et al., 2022; Fischbach et al., 2022). From this evidence, we propose the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 4.

Perceptions of environmental cleanliness positively influence WTP for CBT-CP.

3. Methods

3.1. Contingent Valuation Method (CVM)

CVM is a popular method applied across many disciplines. Community-based tourism (CBT) has emerged as a significant model that promotes local economic growth, cultural preservation, and environmental stewardship amid the growing global emphasis on sustainable development. CBT directly supports sustainability principles by equitable benefit-sharing, local participation, and the preservation of natural resources and cultural traditions (Jackson, 2025). In this context, CVM offers a rigorous method for quantifying public support, particularly individuals’ willingness to pay (WTP), for projects/programs that promote inclusive, locally driven tourism and preserve intangible cultural assets (Koumoutsea et al., 2023).

In this study, we utilized the CVM approach to develop and administer a structured survey designed to elicit respondents’ WTP for a proposed project in Lac Village. This project focuses on cultural heritage preservation and the advancement of community-based tourism. To ensure the validity and credibility of our contingent valuation (CV) survey, we followed the methodological guidelines outlined by (Arrow et al., 1993; Champ et al., 2017). These guidelines underscore the importance of presenting respondents with a realistic and credible depiction of the proposed project’s implementation. Failure to provide such context can lead participants to perceive the scenario as hypothetical or impractical, thereby generating unreliable or biased responses (Arrow et al., 1993; Champ et al., 2017). Consequently, our questionnaire featured a meticulously constructed scenario that thoroughly explained the project’s feasibility and institutional arrangements. Respondents were informed that local government authorities would oversee the initiative, and all financial contributions would be transparently allocated. These funds would specifically support the preservation of the cultural identity of the Thai ethnic minority in Lac Village and facilitate the development of the area into an appealing and sustainable community-based tourism destination.

The academic literature commonly identifies three main question formats (questions). The first format is open-ended, which directly asks respondents to state their maximum WTP. In contrast, the payment card format presents respondents with a pre-defined list of WTP amounts, from which they select the highest acceptable contribution. The third approach, dichotomous choice, offers a specific monetary amount and requires a binary “yes” or “no” response regarding its alignment with the respondent’s WTP. Of these methods, the payment card format (question) is particularly suitable for surveying young respondents. This group frequently demonstrates elevated awareness, technological proficiency, and greater access to information pertinent to cultural values and sustainable tourism. Moreover, young individuals are pivotal in disseminating and promoting community-based tourism initiatives through their extensive social networks and peer influence.

Considering its proven efficiency, simplicity, and ability to yield robust WTP estimates (Champ et al., 2017), the payment card method was selected for this study. However, to address potential biases such as range effects (where interval selection is influenced by the card’s price bounds) and anchoring (where initial amounts skew responses), we pre-tested the card intervals to align with local youth income levels and randomized presentation order. To be specific, the payment card method was employed to survey young tourists visiting and engaging with Lac Village. The questionnaire’s WTP section began by asking respondents if they would be willing to contribute financially to a community-based tourism associated with cultural heritage preservation fund (Box 1). Those who agreed to contribute the fund then advanced to the subsequent stage, where the enumerator presented a payment card and instructed them to identify the maximum amount they would be prepared to donate to the fund.

Box 1. Payment card format used in the Lac village questionnaire.

Assume that Lac Village establishes a community-based tourism associated with cultural preservation (CBT-CP) Fund to improve community-based tourism service in the future. Specifically, this fund is used for supporting local people in learning both the native language and foreign languages, addressing environmental issues, and preserving the natural landscape of Lac Village. Would you be willing to contribute a certain amount of money to this CBT-CP fund?

☐ Yes ☐ No

If yes, please let us know the maximum amount you are willing to pay for the CBT-CP fund within the following levels (Unit: Thousand Vietnam Dong).

| ☐ > 1000 | ☐ 1000 | ☐ 900 | ☐ 800 | ☐ 700 |

| ☐ 600 | ☐ 500 | ☐ 400 | ☐ 350 | ☐ 300 |

| ☐ 250 | ☐ 200 | ☐ 150 | ☐ 100 | ☐ 80 |

| ☐ 60 | ☐ 50 | ☐ 40 | ☐ 20 | ☐ 0 |

3.2. Data Collection

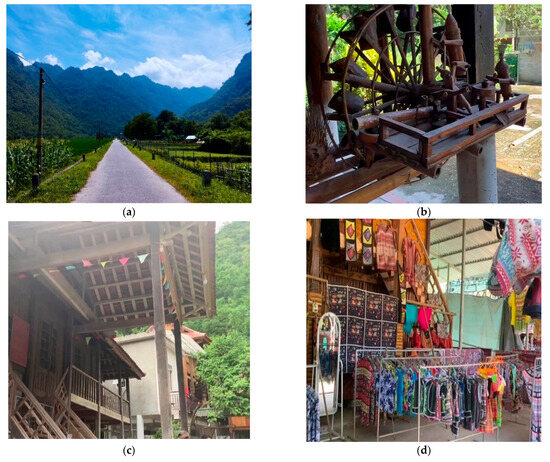

The empirical investigation was conducted in Lac Village, Mai Chau Ward, Phu Tho Province—an exemplary case of community-based tourism (CBT) in Vietnam. This site was purposively selected due to its strong alignment with the study’s objectives and its culturally rich context, which is predominantly inhabited by the White Thai ethnic group. The village is renowned for its well-preserved heritage, including stilt houses, brocade weaving, folk arts, and traditional cuisine, all of which are actively integrated into tourism activities. These elements create an ideal setting for examining the interplay between tourism development and cultural preservation. Over the past two decades, Lac Village has embraced core CBT principles—characterized by local ownership, community participation, and a commitment to socio-cultural and ecological sustainability—that mirror global CBT frameworks and bolster its value for comparative research. In recent years, it has increasingly drawn young, tech-savvy domestic and international travelers seeking authentic and responsible experiences, making it particularly pertinent to this study’s focus on youth engagement. Figure 1 illustrates these key aspects of the village’s tourism landscape: a scenic access road framed by the Pu Luong mountain range (Figure 1a); a traditional waterwheel model representing local irrigation practices (Figure 1b); characteristic stilt houses serving as homestays (Figure 1c); and a vibrant local market displaying brocade and handmade textiles (Figure 1d). Collectively, these images highlight the seamless integration of cultural identity, natural beauty, and community-driven tourism that positions Lac Village as a vibrant, living cultural destination.

Figure 1.

Cultural and community-based tourism experiences in Lac Village, Phu Tho. Source: authors. (a) The road to Lac Village beneath the Pu Luong mountain range. (b) Traditional waterwheel model. (c) Traditional stilt house of the White Thai ethnic group. (d) Brocade and local handicraft market.

Building upon its contextual relevance and pedagogical value, Lac Village served as the destination for a field-based learning program organized by the Faculty of Development Economics, VNU University of Economics and Business. A two-day study tour was conducted in July 2024, during which students directly experienced various aspects of community-based tourism and cultural heritage preservation. This program aimed to bridge academic theory with local development practice, allowing students to explore economic models in situ, sharpen their analytical and evaluative skills, and develop teamwork, communication, and presentation abilities in real-world settings. Embedded within this initiative, a targeted research project examined young tourists’ perceptions and behaviors toward environmental-cultural sustainability and CBT. To implement this project, two survey rounds were conducted: the first in the second week of December 2024 and the second in the second week of August 2025. The focus on young participants—specifically university students aged 18–24—was conceptually justified, as this demographic not only embodies a rapidly expanding tourist segment but also serves as key cultural disseminators, experiential learners, and future tourism consumers. Moreover, this emphasis aligns with higher education’s broader pedagogical objectives of nurturing cultural awareness, national pride, and sustainability-oriented behaviors among the next generation. In particular, the study delved into two core dimensions: (i) the environmental-cultural values reflected in youth attitudes and actions; and (ii) their sense of responsibility in advancing sustainable tourism, evidenced by their willingness to support the Community Cultural Preservation and Tourism Development Fund in Lac Village and similar initiatives nationwide.

Primary data were collected using a mixed-methods approach that combined online surveys (via Google Forms) with face-to-face interviews during an evening cultural immersion session. A total of 275 university student participants (aged 18–24), all of whom had direct exposure to Lac Village’s tourism setting, provided responses yielding valuable empirical insights grounded in authentic experiences. Although the sample was limited to university students—potentially constraining its generalizability to the broader youth tourist population—the exploratory nature of this study afforded a unique opportunity to capture generational perspectives within an authentic CBT context. Convenience sampling and the modest sample size further limit broader applicability, yet these constraints align with the research’s focus on in-depth, context-specific insights. To address potential biases in self-reported willingness to pay (WTP), we implemented several safeguards: clear contextual framing of the proposed funding mechanism to enhance scenario realism, anonymized responses to minimize social desirability effects, and triangulation of quantitative survey data with qualitative interview findings. These measures strengthened the dataset’s internal validity and overall credibility.

3.3. Models

3.3.1. Logistic Regression

In this study, WTP participation was designed with two levels. The first level determines whether individuals are willing to voluntarily pay for CBT-CP, while the second one estimates the amount of their WTP contribution. To investigate the first level, we use a logit model to identify the determinants of the voluntary payment decision. Following James et al. (2021) and Peng et al. (2002), the empirical model is developed as follows:

where π is the event probability. The variables with the subscript ‘i’ represent the characteristics of each individual participant in the survey. The dependent variable is a binary variable, WTP, which takes the value 1 if respondent ‘i’ is willing to pay any positive amount for CBT–CP, and 0 otherwise. The independent variables can be categorized as the socio-demographic factors (Gender, EcoCondition, TravelFreq, SelfFinStatus, BirthPlace) and the perception of tourism service and attribute factors (LocationAccessibility, PriceSuit, LocalCuisine, CleanEnvironment, CultExp, ConCulture, ConEnviquality, SpecVarious, CleanAccommodation). β0 is the intercept of the model. It represents the log-odds of a positive WTP decision when all other predictor variables are zero. β1 to β14 are the regression coefficients for each predictor variable. Each coefficient represents the change in the log-odds of making a voluntary payment for a one-unit increase in the corresponding variable, while holding all other variables constant.

After estimating the logit model for the WTP decision, we use the ROC curve to assess the model’s discriminatory ability. The ROC (Receiver Operating Characteristic), originating from Signal Detection Theory, is now widely used to evaluate binary classification models. Each point on the ROC corresponds to a (sensitivity, 1—specificity) pair obtained by varying the classification threshold on predicted probabilities (Fawcett, 2006). Curves that bend toward the upper-left corner indicate stronger discrimination. Overall accuracy is measured by the area under the curve (AUC), where 0.5 indicates chance performance and values approaching 1 indicate strong discrimination. Standard thresholds classify AUC as: ≤0.50 (poor), 0.50–0.60 (very weak), 0.60–0.70 (fair), 0.70–0.80 (acceptable), 0.80–0.90 (good), and >0.90 (excellent).

3.3.2. Interval Regression

To estimate respondents’ WTP for improving CBT-CP in Lac Village, we employ an interval regression model—an extension of censored regression techniques—particularly suitable when the exact value of the dependent variable is not directly observed but known to lie within an interval. This method is appropriate for contingent valuation data obtained through the payment card method, which presents respondents with a range of monetary values (Champ et al., 2017; Dong & Zeng, 2018).

Formally, consider a series of bid levels 0 ≤ p1 < p2 < p3 < ··· < pn on the payment card (with pn potentially approaching infinity). Let be respondent i’s reported WTP and be their true valuation. Then,

Adopting Champ et al. (2017), we specify the estimation equation as follows:

It is noted that the error term follows N(0, σ2), and β are the variable and coefficient vectors respectively. Respondent i’s response falls in [, ], where = and = for some k ∈ {1, 2, …, n − 1}. The probability of i’s true WTP being in [, ] follows the below equation:

We obtained the mean of WTP by the following equation (Champ et al., 2017):

By applying this model, we can rigorously quantify the economic value that respondents attach to CBT-related services and cultural heritage in a rural, ethnic minority context. In this study, the target population consists predominantly of young tourists, who travel to Lac Village to explore traditional Thai culture, enjoy natural landscapes, and engage in local activities such as ethnic dance performances, culinary experiences, and homestays in stilt houses. The application of the interval regression model not only captures their economic preferences but also reflects the perceived cultural value associated with the intangible assets of the community—such as ethnic costumes, traditional housing, local crafts, folklore, etc. These elements form the core identity of the Thai ethnic group and represent the primary appeal of CBT in Lac Village.

Based on research hypotheses and the theoretical framework of voluntary payment, we develop an empirical model of willingness to pay (WTP) for cultural heritage preservation and the development of community-based tourism in the study area. The proposed empirical model (2) is specified as follows:

WTPi = β0 + β1Genderi + β2EcoConditioni + β3TravelFreqi + βSelfFinStatusi

+ β5BirthPlacei + β6LocationAccessibilityi + β7PriceSuiti + β8LocalCuisinei

+ β9CleanEnvironmenti + β10CultExpi + β11 ConCulturei + β12ConEnviqualityi

+ β13SpecVariousi + β14CleanAccommodationi + εi

+ β5BirthPlacei + β6LocationAccessibilityi + β7PriceSuiti + β8LocalCuisinei

+ β9CleanEnvironmenti + β10CultExpi + β11 ConCulturei + β12ConEnviqualityi

+ β13SpecVariousi + β14CleanAccommodationi + εi

Details of the independent variables in the experimental model (2) are shown in detail in Table 1 below:

Table 1.

Description of variables.

4. Results

4.1. Young Visitors’ Perceptions and Experiences of CBT

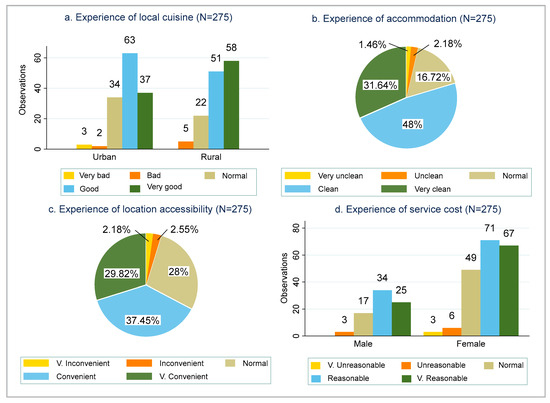

When asked to describe community-based tourism (CBT), it can be seen that respondents often approach it from two basic dimensions. The first is the experience and service quality aspect that they directly receive during their participation, including the diversity of tourism activities, the usefulness of services, as well as the convenience in organizing and meeting the needs of tourists (Figure 2). This is a group of factors that reflect the availability and value of community-based tourism products.

Figure 2.

Dimensions of service quality in tourists’ experiences of community-based tourism.

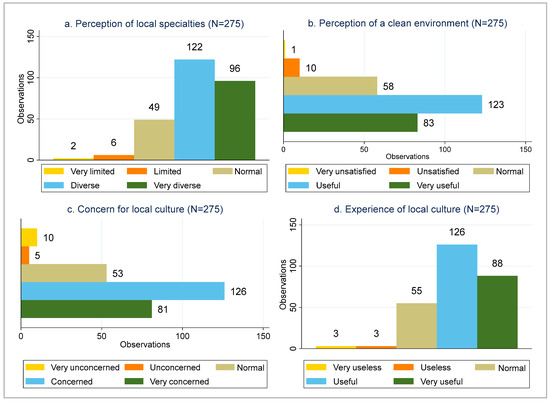

Second, respondents focus on the perception of the intangible value of the destination, expressed through the cleanliness of the environment, the diversity of local specialties, the level of cultural identity preservation, and the ability to create opportunities to contribute to the local community (Figure 3). This group of factors reflects the level of tourists’ attachment to sustainable values, as well as empathy and social responsibility during their participation in CBT.

Figure 3.

Perceptions and experiences of cultural and environmental aspects of community-based tourism.

The combination of the two dimensions mentioned above—one emphasizing the tangible through service quality, and the other reflecting the intangible values of the environment, culture and community—allows for a more comprehensive view of how tourists, especially young tourists, evaluate the CBT model. This shows that CBT is not only viewed as a type of tourism service, but also as a socio-cultural mechanism that contributes to promoting sustainable development at the local level.

Figure 2 illustrates the high level of satisfaction of tourists with their CBT experience at Lac Village across four dimensions. Local cuisine (sticky rice) was positively rated by both rural and urban visitors, with rural participants reporting slightly higher ratings (Figure 2a). Nearly 80% of respondents rated the accommodation as excellently clean (Figure 2b), while 67.27% found the accommodation convenient for travel and activities (Figure 2c). Service costs were considered reasonable by both genders, with women reporting higher levels of satisfaction (Figure 2d). These findings suggest that tangible service attributes—such as food quality, hygiene, accessibility, and affordability—were effectively maintained. From a service quality perspective, these elements represent a balance between technical quality (the outcome of the service) and functional quality (the way the service is delivered), which together form the basis of customer evaluation (Phan et al., 2013), and tangible aspects play an important role in customer perception and satisfaction formation (H. M. Nguyen et al., 2015).

Figure 3 reflects tourists’ positive perceptions of the intangible aspects of community-based tourism. Respondents reported that local specialties were diverse (Figure 3a), and nearly 75% were satisfied or very satisfied with the environmental conditions (no plastic waste, cleanliness, and beautiful scenery) (Figure 3b). Similarly, cultural experiences were rated as very or very useful by 78% of respondents, with a strong interest in preserving cultural heritage (Figure 3c,d). These results demonstrate that in addition to tangible service elements, environmental cleanliness, cultural authenticity, and empathy for local traditions (intangible components of service quality) play a central role in significantly increasing tourist satisfaction and loyalty.

In short, the findings suggest that tourists’ evaluations of CBTs are shaped not only by tangible service attributes such as food, cleanliness, accessibility, and affordability, but also—more decisively—by intangible aspects of service quality including environmental hygiene, cultural experiences, and empathy, which together reinforce satisfaction, loyalty, and attachment to sustainable community values.

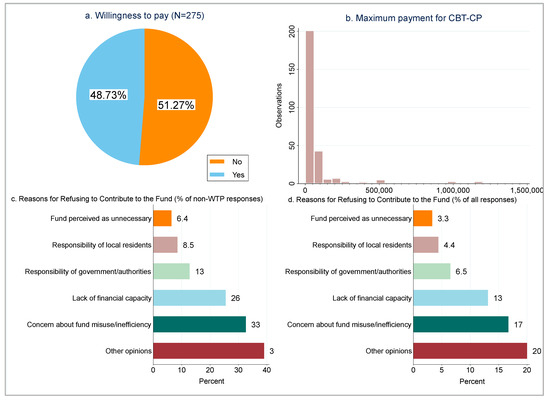

4.2. WTP and Non-WTP for Improved CBT-CP

Figure 4 shows a significant discrepancy between positive attitudes towards CBT and actual financial contributions. While visitors expressed strong concerns about cultural heritage and environmental protection, only 48.73% said they would be willing to make a financial contribution, with over 70% choosing the lowest contribution level and only a small fraction willing to pay more than VND 500,000 (~USD 19.2) (Figure 4a,b). Furthermore, 141 respondents said they would not contribute, citing reasons such as doubts about the effectiveness of the fund, financial constraints, or the belief that the responsibility lies with the government or local community (Figure 4c,d). This difference highlights what the service quality literature identifies as the gap between expectations and perceived outcomes: even when satisfaction with cultural and environmental aspects is high, governance concerns and limited financial capacity reduce tourists’ willingness to act (Phan et al., 2013).

Figure 4.

Willingness to Pay and Not Willing to Pay for Improved CBT-CP.

4.3. Determinants of Young Visitors’ WTP for Improved CBT-CP

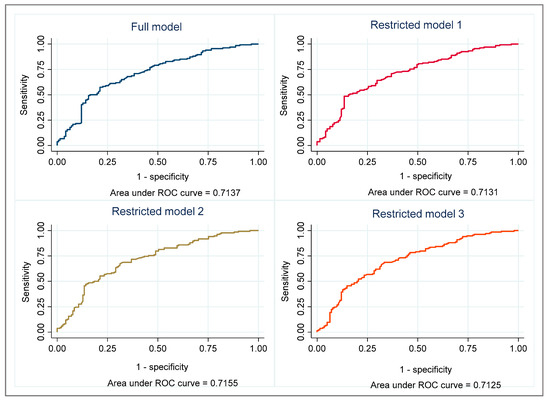

Table 2 presents results from four logit models estimating youth WTP participation for CBT-CP. The full model (FM) incorporates all explanatory variables, while restricted models (RM1-RM3) exclude subsets for comparison. All models demonstrate strong statistical significance (p < 0.01), confirming their overall reliability at the 99% confidence level. Model fit, assessed via log-likelihood, favors the FM (−170.22), indicating a superior fit to the data, and therefore FM will be selected for our reporting and interpretation. ROC curve analysis (Figure 5) further reveals comparable predictive accuracy across models, with AUC values of 0.713–0.716—enabling ~71% discrimination between WTP participants and non-participants.

Table 2.

Logit model’s estimated results of WTP participation.

Figure 5.

ROC curves of logistic regression models predicting willingness to pay (WTP).

The full model (FM) includes 14 explanatory variables, 6 of which are statistically significant at the 10%, 5% and 1% confidence levels (Table 2). These variables are ConEnviquality SelfFinStatus, PriceSuit, LocalCuisine, CleanEnvironment and CultExp. First, the variable ConEnviquality has a positive and statistically significant effect (0.379, p < 0.1) on the dependent variable. This suggests that young visitors who express greater concern for environmental quality and scenic value are more inclined to contribute financially, highlighting that ecological awareness translates into stronger support for CBT-CP. Next, SelfFinStatus has a coefficient of 0.379, which is statistically significant at the 10% level, indicating a one-unit increase in respondents’ financial self-assessment (e.g., from “normal” to “good”) corresponds to a 0.379 increase in the log-odds of participating in WTP. Put differently, youths who perceive themselves as financially secure are more willing to participate, underscoring the role of disposable income in heritage-related tourism support.

Next, the variable PriceSuit has a negative and statistically significant effect (–0.661, p < 0.05) on the dependent variable. This confirms that perceptions of higher accommodation or living costs act as a deterrent: when affordability concerns dominate, youths reduce their willingness to contribute, even when they value cultural heritage. In addition, the variable LocalCuisine has a coefficient of 0.635, which is statistically significant at the 5% level. This indicates that a one-unit improvement in respondents’ evaluation of local cuisine (e.g., from “normal” to “good”) leads to a 0.635 increase in the log-odds of being willing to pay for CBT-CP. This finding indicates that more favorable evaluations of local cuisine are associated with a higher willingness to contribute.

For the CleanEnvironment variable, the coefficient of –0.830 indicates a negative and highly statistically significant effect (p < 0.01). Although counterintuitive, this suggests that when young visitors already perceive the environment as very clean, they feel less urgency to support CBT-CP financially. In contrast, if environmental shortcomings are apparent, WTP may increase as youths see their contribution as addressing a tangible need. Finally, the CultExp variable has a coefficient of 0.672, which is highly statistically significant (p < 0.01). This indicates that cultural immersion is a decisive motivator: youths who find local cultural experiences useful and enjoyable are substantially more willing to pay, reflecting generational preferences for authentic, experience-driven tourism. In summary, youth support for CBT-CP is primarily shaped by cultural and experiential values (LocalCuisine, CultExp), financial self-confidence (SelfFinStatus), and environmental concern (ConEnviquality), while affordability constraints (PriceSuit) and perceived environmental adequacy (CleanEnvironment) dampen participation.

Table 3 presents the estimated results from five distinct models. FM represents the full model, which includes all variables, while RM1 through RM4 are restricted models, each excluding a subset of the variables. An important point is that all five models exhibit p-values below 0.01. This suggests that each model is statistically significant, allowing us to be 99% confident that the estimated coefficients are not equal to zero. This confirms the overall statistical reliability of all models presented. To identify the best-fitting model, we compared their log-likelihood values. A higher log-likelihood value signifies a better model fit. Because FM (the full model) has the highest log-likelihood value, it is mainly used for our report and interpretation.

Table 3.

Estimated results of the interval regression model for WTP.

The full model (FM) includes 14 explanatory variables, 5 of which are statistically significant at the 5% and 1% confidence levels (Table 3). These variables are LocationAccessibility, LocalCuisine, CultExp, PriceSuit, and CleanEnvironment. First, LocationAccessibility has a coefficient of 0.496 (p < 0.05), suggesting that visitors who perceive accommodation as conveniently located are about 49.6% more willing to pay (WTP). This implies that good transport connections not only reduce travel burdens but also increase tourists’ willingness to support CBT-CP, as accessibility signals a more visitor-friendly destination. Next, the variable PriceSuit has a negative and highly statistically significant effect (−0.630, p < 0.05) on the dependent variable. This means that a one-unit increase in PriceSuit (i.e., respondents’ perceived living/accommodation costs increase from “Normal” to “Reasonable”) results in a 63.0% decrease in WTP for CBT-CP. In practical terms, this means that when visitors find local accommodation expensive, affordability concerns outweigh cultural or experiential appeal, discouraging financial support for CBT-CP. The LocalCuisine variable has a positive coefficient of 0.479, which is statistically significant at the 5% level. This result indicates that visitors place strong value on culinary experiences: when they perceive local food as tastier and reasonably priced, their WTP rises by nearly 48%. This finding resonates with the broader trend that tourists often engage with culture first through cuisine, suggesting that food can be a gateway to heritage-oriented tourism.

For the CleanEnvironment variable, the coefficient of −0.724 indicates a negative and highly statistically significant effect (p < 0.01). This means that a one-unit increase in respondents’ agreement with the statement that the environment is free of plastic or other waste (e.g., from “Strongly disagree” to “Disagree”) would cause a 72.4% decrease in WTP. Although counterintuitive, this finding may reflect visitors’ expectations: tourists who strongly agree that the environment is already clean may perceive less urgency to financially support CBT-CP initiatives. In contrast, those perceiving environmental shortcomings may feel that contributions to CBT-CP are needed to address such issues. Finally, the CultExp variable has a coefficient of 0.572 with a high statistical significance level (p < 0.01). This demonstrates that when a respondent’s perception of the usefulness and enjoyment of local cultural experiences increases by one unit (e.g., from “Normal” to “Useful”), WTP increases by 57.2%. Notably, younger or more culturally motivated travelers may prioritize authentic experiences over cost considerations. In summary, the evidence suggests that accessibility, cuisine, and cultural experience are powerful motivators for supporting CBT-CP, whereas higher accommodation costs discourage participation, and environmental perceptions shape support in less straightforward ways.

Table 4 presents a summary of the estimated WTP values and corresponding total revenue by model and certainty level. It is noted that WTP1 is the willingness-to-pay value for CBT-CP for full model (M1), which incorporates responses across the complete certainty spectrum from very uncertain (level 1) to very certain (level 10), including zero WTP responses. WTP2 refers to the willingness-to-pay value for restricted model (M2) that focuses exclusively on responses from certain (levels 7–8) to very certain (levels 9–10) participants.

Table 4.

Estimated results of WTP and total revenue by model and certainty level.

As shown in Table 4, there are two key patterns presented. First, the full model (M1) yields an estimated WTP1 of 115.9 kVND per visit for CBT-CP, leading to a total estimated revenue of USD 2413.2. Second, although the restricted model M2 shows higher individual WTP values than the full model M1, its total estimated revenue is paradoxically lower. More precisely, WTP2a and WTP2b for CBT-CP at certain and very certain levels are 144.4 kVND and 137.4 kVND per visit, respectively, yielding total estimated revenues of USD 1541.7 and USD 624.1, respectively. In short, these results reveal a substantial variation in total estimated revenue (USD 624.1 to USD 2413.2) that directly correlates with participant certainty levels within the study population. The more detailed WTP estimated for each model associated with certainty levels is presented in Appendix A.1, Appendix A.2 and Appendix A.3.

5. Discussion

Community-based tourism (CBT) is important for the people in mountainous regions, impacting their well-being, spiritual and/or cultural life. However, it is an evident fact that CBT faces numerous challenges, including environmental degradation and pollution, financial constraints, and poor management practices (Baloch et al., 2023; Jackson, 2025). This study aims to explore the financial contribution of tourists and the factors influencing it, thereby providing solutions to help improve the CBT-CP (Community-based tourism coupled with cultural preservation) model in Vietnam. This section further presents and/or discusses the key empirical results, their implications and the limitations of the study.

As expected, the variables of LocationAccessibility, LocalCuisine, and CultExp exert positive influences on WTP for CBT-CP (Table 3). These dimensions operate as proxies for service quality, a factor long recognized as central to tourist satisfaction and their intention to return (Dai et al., 2025; H. M. Nguyen et al., 2015). In practice, convenient access, authentic cuisine, and immersive cultural activities are not peripheral elements but the very foundation of tourists’ evaluations of CBT experiences. Yet, the evidence indicates a persistent mismatch between demand-side expectations and supply-side realities. In Lac village, infrastructure limitations, modest hospitality standards, and underdeveloped cultural programming restrict the capacity to transform favorable perceptions into consistent contributions, thereby reducing revenue potential and threatening long-term competitiveness. Beyond service quality, the results also reveal paradoxes in the negative associations between CleanEnvironment and WTP as well as PriceSuit and WTP. In the case of environmental quality, tourists who perceive conditions as already clean often view additional contributions as unnecessary and expect responsibility to rest with local authorities or the broader community. In contrast, visible degradation heightens their sense of moral responsibility, motivating stronger personal engagement. This pattern reflects a free-rider tendency, whereby individuals are content to enjoy collective benefits but prefer others to bear the costs once minimum standards are achieved. A comparable mechanism emerges in relation to cost perceptions. When visitors believe accommodation and living expenses are already reasonable, they often perceive their spending as a sufficient form of support, thereby reducing willingness to make further contributions. In effect, regular expenditures are treated as substitutes for voluntary payments—once tourists feel they have paid a fair price, their motivation to add more support diminishes.

For managers of CBT-CP, these dynamics pose a delicate challenge. Maintaining clean environments and fair prices is essential for ensuring visitor satisfaction, yet these very conditions can paradoxically weaken incentives for additional contributions. This underscores the importance of designing mechanisms that preserve satisfaction while sustaining financial support. Possible strategies include transparent reporting of how contributions are used, awareness campaigns that emphasize shared responsibility, and innovative approaches such as linking small voluntary fees to visible cultural or environmental preservation projects. Importantly, young tourists remain highly attentive to environmental risks and play a pivotal role in both consumption and contributions (Abdullah et al., 2024; Dardanoni & Guerriero, 2021; Pasanchay & Schott, 2021). The more they perceive environmental challenges, the more they are inclined to provide financial support. Taken together, these findings highlight the dual importance of service quality and environmental management while offering practical insights into how young tourists’ awareness and engagement can be leveraged to strengthen the CBT-CP model.

The study’s findings have three key implications. First, it demonstrates the feasibility of mobilizing financial resources for CBT-CP development. Our findings show that the aggregate revenue collected from young visitors is estimated to range from USD 624.1 to USD 2413.2 (Table 4). Local communities can even achieve the highest revenue by improving communication about the quality of their on-site services and real-life experiences, particularly cultural ones. For example, enhancing cultural experiences could increase tourist contributions by up to 61.6% (Table 3). However, reasons cited for a lack of Willingness to Pay (WTP) (Figure 4c,d) suggest that leveraging this funding source remains challenging in areas where a transparent financial culture is not yet common. When it comes to the exploration of tourism culture and the opportunity for educating young people on it, in this study tourism culture can be understood as the process of awareness, experience, and contribution to CBT-CP (Khuc, 2023; Liang et al., 2023; Oltean et al., 2025). It is crucial for the tourism sector to help young people fully recognize the importance of cultural values from community-based tourism so they are always motivated to protect the environment and support efforts to improve the quality of CBT services. It is important to note that the tourism culture associated with local cultural preservation reflects the demand of young people (Schönherr & Pikkemaat, 2024), and the underlying value is their patriotism and love for the native culture that they want to pass on to future generations. Third and most importantly, is promoting tourism culture to foster economic development (Suyatna et al., 2024; Thao & Bakucz, 2024). This is essential because Vietnam has significant potential for tourism-based economic development, particularly through eco-tourism, experiential tourism, and educational tourism (Loan, 2023; Q. N. Nguyen et al., 2024). To leverage this unique advantage, the tourism culture of visitors can provide local residents with the necessary financial investment to build and upgrade their CBT-CP management models (Khuc et al., 2024; Ngo & Creutz, 2022). This should be integrated with digital, green, clean, and creative transformations to improve both service pricing and service quality—the central elements for CBT development.

This study offers a significant contribution to both the literature and practices regarding the CBT-CP development model, which is centered on young tourists. Within this framework, three key elements—finance, service quality, and tourists—are identified as decisive for sustainable tourism development. Additionally, the study’s identification of factors influencing participation and contribution to CBT-CP strengthens the foundation for future tourism policies and solutions. While Vietnam has promoted tourism through various macro-policies—such as the Tourism Law 2017 and the Tourism Development Strategy to 2030—to position the country among the top three tourist destinations in Southeast Asia and emphasize green, sustainable, and culturally rooted development (Decision 147/QĐ-TTg, 2020; Law on Tourism, 2017), specific policies for CBT-CP still require further refinement. More broadly, a second major contribution of this research lies in its theoretical insights into tourism-based economic development and services, specifically through the CBT-CP model in mountainous regions. The study highlights the need for continued research to further develop the theory of green economic development through the promotion of tourism culture.

The study has three main limitations. First, the limited scope of the research to a single site, Lac village, and a small sample size (i.e., 275 observations) may hinder the generalizability of the findings to some degree. Second, the study has not developed a specific tourism culture index yet, nor has it fully explained the underlying mechanism of tourist decision-making. In this sense, future research should address this by creating a comprehensive index. Third, more advanced methodological models are needed to fully explore the complex relationships and mechanisms within this topic. A CBMM approach (Khuc et al., 2024), for instance, could provide a more profound understanding in future studies.

6. Conclusions

This study advances the understanding of young visitor-based community-based tourism associated with cultural heritage conservation (CBT-CP) for sustainable livelihood for ethnic minority communities in mountainous regions in Vietnam. By employing a rigorous, CVM-based analysis of young travelers’ perceptions and their willingness to pay (WTP) for CBT-CP, we have developed a novel framework and/or approach for understanding and leveraging financial support from visitors. Our findings confirm that young tourists represent a significant, yet underutilized, source of funding for cultural preservation, with their preferences aligning both with economic viability and cultural integrity. Rather than reiterating individual determinants, three overarching insights emerge. First, retaining visitors who already show strong commitment can foster deeper participation and encourage greater contributions over time. Second, strengthening transparency and accountability in fund management is essential for overcoming reluctance and building governance trust. Third, providing clear and accessible information on how contributions are allocated can transform potential support into actual financial flows. Our study makes at least a twofold contribution. Theoretically, it contributes to the literature on sustainable tourism by introducing and/or examining, for the first time, a financial development model of CBT-CP attributable to young visitors using the advanced method of CVM. Practically, the proposed solutions provide a relatively clear path for the effective implementation and development of CBT-CP projects in Lac Village and other similar tourism destinations. Looking ahead, future research should extend this analysis along several promising directions. First, comparative studies across different ethnic minority villages are needed to examine how cultural, institutional, and geographic variations shape young tourists’ willingness to contribute. Second, the inclusion of international tourists in future surveys would provide insights into cross-cultural differences in motivations and support, thereby enhancing the generalizability of findings. Beyond these avenues, further work could adopt an explicitly generational perspective by comparing young visitors with other age groups to determine whether their values, motivations, and financial commitments are distinctive or part of broader tourist behaviors. In addition, examining how digital tools—such as mobile applications, e-payment systems, or online transparency platforms—shape young tourists’ trust and willingness to pay would shed light on the role of technology in sustaining CBT-CP initiatives. Longitudinal studies that track whether young tourists maintain, increase, or reduce their willingness to contribute over multiple visits could also provide important evidence on the durability of their engagement. Finally, expanding the scope beyond direct financial contributions to include indirect forms of support—such as cultural promotion through social media, voluntary participation, or peer-to-peer advocacy—would allow for a more comprehensive understanding of the multifaceted ways in which young tourists strengthen CBT-CP. Finally, this study demonstrates the power of tourism culture and a mutually beneficial linkage between mindful tourism and community-led preservation, paving the way for more sustainable tourism and a more sustainable future for ethnic minority communities in Vietnam and beyond.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.Q.K.; Methodology, V.Q.K. and D.N.D.; Validation, V.Q.K. and A.T.N.; Formal analysis, V.Q.K. and D.N.D.; Resources, V.Q.K.; Data curation, V.Q.K., A.T.N., K.C.L., T.T.T., D.H.L. and T.H.N.; Writing—original draft, V.Q.K., D.N.D., A.T.N., K.L.H., K.C.L., T.T.T., D.H.L., T.H.N., T.Q.T.T. and P.T.D.; Writing—review and editing, V.Q.K., D.N.D., A.T.N., K.L.H., K.C.L., T.T.T., D.H.L., T.H.N., T.Q.T.T. and P.T.D.; Project administration, V.Q.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval was waived for this study due to the ethics guidelines from the National Guidelines on Biomedical Research Ethics and several established Vietnamese universities (https://fulbright.edu.vn/en/irb/ and https://www.rmit.edu.vn/research/research-ethics-integrity).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patients to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets utilized in the present investigation can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all participants who assisted us with the data collection for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AUC | Area under the curve |

| CBT | Community-based tourism |

| CP | Cultural heritage preservation |

| CBT-CP | Community-based tourism linked to cultural heritage preservation |

| CVM | Contingent valuation method |

| ROC | Receiver operating characteristic |

| WTP | Willingness to pay |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Table A1.

The estimated results of WTP for CBT-CP by models with all certainty level (1–10).

Table A1.

The estimated results of WTP for CBT-CP by models with all certainty level (1–10).

| Variables | MWTP (FM) | MWTP (RM1) | MWTP (RM2) | MWTP (RM3) | MWTP (RM4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | −0.107 | −0.108 | −0.102 | −0.0788 | −0.0764 |

| (0.268) | (0.268) | (0.268) | (0.268) | (0.269) | |

| BirthPlace | 0.0566 | 0.0549 | 0.0527 | 0.00781 | 0.00210 |

| (0.243) | (0.243) | (0.243) | (0.241) | (0.243) | |

| EcoCondition | −0.0612 | −0.0572 | −0.0469 | −0.0528 | −0.0549 |

| (0.258) | (0.257) | (0.256) | (0.256) | (0.258) | |

| TravelFreq | 0.259 | 0.259 | 0.252 | 0.268 | 0.288 |

| (0.176) | (0.176) | (0.175) | (0.175) | (0.176) | |

| SelfFinStatus | 0.179 | 0.180 | 0.179 | 0.170 | 0.194 |

| (0.202) | (0.202) | (0.202) | (0.202) | (0.203) | |

| LocationAccessibility | 0.496 ** | 0.497 ** | 0.491 ** | 0.494 ** | 0.495 ** |

| (0.233) | (0.233) | (0.232) | (0.234) | (0.235) | |

| LocalCuisine | 0.479 ** | 0.481 ** | 0.421 ** | 0.443 ** | 0.472 ** |

| (0.243) | (0.243) | (0.209) | (0.210) | (0.211) | |

| CultExp | 0.572 *** | 0.573 *** | 0.561 ** | 0.547 ** | 0.618 *** |

| (0.221) | (0.221) | (0.219) | (0.219) | (0.217) | |

| PriceSuit | −0.630 ** | −0.629 ** | −0.636 ** | −0.624 ** | −0.522 ** |

| (0.258) | (0.258) | (0.257) | (0.259) | (0.251) | |

| CleanEnvironment | −0.724 *** | −0.726 *** | −0.735 *** | −0.711 *** | −0.537 *** |

| (0.224) | (0.224) | (0.223) | (0.223) | (0.196) | |

| CleanAccommodation | 0.409 | 0.411 | 0.383 | 0.422 | |

| (0.260) | (0.260) | (0.253) | (0.252) | ||

| ConEnviquality | 0.162 | 0.185 | 0.185 | ||

| (0.209) | (0.148) | (0.148) | |||

| Specvarious | −0.129 | −0.130 | |||

| (0.266) | (0.266) | ||||

| ConCulture | 0.0308 | ||||

| (0.204) | |||||

| Constant | 6.110 *** | 6.110 *** | 6.062 *** | 6.476 *** | 6.556 *** |

| (1.069) | (1.070) | (1.067) | (1.010) | (1.011) | |

| Sigma | 1.737 | 1.738 | 1.739 | 1.744 | 1.756 |

| Log likelihood | −505.87 | −505.88 | −506.0 | −506.80 | −508.22 |

| Prob > chi2 | 0.0000 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 |

| # Observations (N) | 275 | 275 | 275 | 275 | 275 |

| Estimated E [WTP] | |||||

| 116.0 | 116.0 | 115.8 | 115.9 | 115.9 |

| 4.46 | 4.46 | 4.45 | 4.46 | 4.46 |

Notes: *** p-value < 0.01, ** p-value < 0.05. t statistics in parentheses. MWTP denotes magnitude of WTP.

Appendix A.2

Table A2.

The estimated results of WTP for CBT-CP by models with high certainty level (7–10).

Table A2.

The estimated results of WTP for CBT-CP by models with high certainty level (7–10).

| Variables | MWTP (FM) | MWTP (RM1) | MWTP (RM2) | MWTP (RM3) | MWTP (RM4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.0430 | 0.0432 | 0.0437 | 0.0316 | 0.0337 |

| (0.312) | (0.312) | (0.312) | (0.313) | (0.315) | |

| BirthPlace | 0.104 | 0.105 | 0.106 | 0.119 | 0.0897 |

| (0.272) | (0.272) | (0.272) | (0.272) | (0.272) | |

| EcoCondition | −0.186 | −0.187 | −0.182 | −0.162 | −0.145 |

| (0.289) | (0.287) | (0.286) | (0.286) | (0.287) | |

| TravelFreq | 0.310 | 0.311 | 0.310 | 0.296 | 0.305 |

| (0.193) | (0.193) | (0.193) | (0.193) | (0.194) | |

| SelfFinStatus | 0.128 | 0.128 | 0.126 | 0.128 | 0.142 |

| (0.225) | (0.224) | (0.223) | (0.224) | (0.225) | |

| LocationAccessibility | 0.494 * | 0.493 * | 0.493 * | 0.490 * | 0.498 * |

| (0.260) | (0.260) | (0.260) | (0.260) | (0.264) | |

| PriceSuit | −0.370 | −0.373 | −0.385 | −0.378 | −0.351 |

| (0.295) | (0.288) | (0.282) | (0.282) | (0.284) | |

| LocalCuisine | 0.374 | 0.375 | 0.350 | 0.343 | 0.361 |

| (0.273) | (0.272) | (0.245) | (0.245) | (0.247) | |

| CleanEnvironment | −0.483 ** | −0.488 ** | −0.500 ** | −0.516 ** | −0.504 ** |

| (0.243) | (0.215) | (0.207) | (0.207) | (0.208) | |

| CultExp | 0.512 ** | 0.509 ** | 0.501 ** | 0.499 ** | 0.503 ** |

| (0.260) | (0.250) | (0.247) | (0.248) | (0.250) | |

| ConCulture | 0.263 | 0.262 | 0.261 | 0.149 | |

| (0.217) | (0.216) | (0.216) | (0.146) | ||

| ConEnviquality | −0.157 | −0.157 | −0.155 | ||

| (0.221) | (0.221) | (0.221) | |||

| Specvarious | −0.0579 | −0.0596 | |||

| (0.277) | (0.274) | ||||

| CleanAccommodation | −0.0121 | ||||

| (0.286) | |||||

| Constant | 7.402 *** | 7.408 *** | 7.393 *** | 7.269 *** | 7.488 *** |

| (1.164) | (1.153) | (1.151) | (1.143) | (1.127) | |

| Sigma | 1.460 | 1.460 | 1.460 | 1.466 | 1.475 |

| Log likelihood | −314.7 | −314.7 | −314.7 | −315.0 | −315.5 |

| Prob > chi2 | 0.0267 | 0.0176 | 0.0113 | 0.0081 | 0.0068 |

| # Observations (N) | 141 | 141 | 141 | 141 | 141 |

| Estimated E [WTP] | |||||

| 144.6 | 144.6 | 144.5 | 144.0 | 144.5 |

| 5.56 | 5.56 | 5.56 | 5.54 | 5.56 |

Notes: *** p-value < 0.01, ** p-value < 0.05, * p-value < 0.1. t statistics in parentheses. MWTP denotes magnitude of WTP.

Appendix A.3

Table A3.

The estimated results of WTP for CBT-CP by models with very certainty level (9–10).

Table A3.

The estimated results of WTP for CBT-CP by models with very certainty level (9–10).

| Variables | MWTP (FM) | MWTP (RM1) | MWTP (RM2) | MWTP (RM3) | MWTP (RM4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.727 | 0.728 | 0.720 | 0.716 | 0.710 |

| (0.576) | (0.577) | (0.575) | (0.575) | (0.574) | |

| BirthPlace | 0.791 | 0.803 | 0.800 | 0.785 | 0.788 |

| (0.513) | (0.490) | (0.489) | (0.481) | (0.481) | |

| EcoCondition | −0.805 * | −0.803 * | −0.806 * | −0.796 * | −0.795 * |

| (0.469) | (0.468) | (0.468) | (0.466) | (0.466) | |

| TravelFreq | 0.509 | 0.513 | 0.517 | 0.521 | 0.543 * |

| (0.331) | (0.326) | (0.326) | (0.324) | (0.314) | |

| SelfFinStatus | −0.0137 | −0.0219 | −0.0289 | −0.0273 | −0.0514 |

| (0.395) | (0.380) | (0.378) | (0.378) | (0.366) | |

| LocationAccessibility | 0.752 | 0.755 | 0.752 | 0.763 | 0.802 * |

| (0.483) | (0.483) | (0.481) | (0.480) | (0.466) | |

| PriceSuit | −0.930 * | −0.935 * | −0.966 * | −0.958 * | −0.998 * |

| (0.559) | (0.555) | (0.528) | (0.528) | (0.511) | |

| Specvarious | −0.302 | −0.304 | −0.307 | −0.314 | −0.265 |

| (0.549) | (0.549) | (0.549) | (0.548) | (0.515) | |

| CleanEnvironment | −0.569 | −0.576 | −0.598 | −0.592 | −0.588 |

| (0.420) | (0.410) | (0.391) | (0.390) | (0.390) | |

| CultExp | 1.528 *** | 1.532 *** | 1.521 *** | 1.529 *** | 1.583 *** |

| (0.502) | (0.500) | (0.498) | (0.497) | (0.455) | |

| LocalCuisine | 0.128 | 0.122 | 0.119 | 0.131 | |

| (0.504) | (0.497) | (0.497) | (0.494) | ||

| ConEnviquality | 0.0531 | 0.0753 | 0.0571 | ||

| (0.449) | (0.338) | (0.322) | |||

| CleanAccommodation | −0.0975 | −0.0830 | |||

| (0.507) | (0.469) | ||||

| ConCulture | 0.0293 | ||||

| (0.392) | |||||

| Constant | 7.546 *** | 7.573 *** | 7.632 *** | 7.688 *** | 7.814 *** |

| (1.866) | (1.834) | (1.801) | (1.774) | (1.705) | |

| Sigma | 1.487 | 1.488 | 1.487 | 1.489 | 1.488 |

| Log likelihood | −117.5 | −117.5 | −117.6 | −117.6 | −117.6 |

| Prob > chi2 | 0.0635 | 0.0441 | 0.0297 | 0.0192 | 0.0120 |

| # Observations (N) | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 |

| Estimated E [WTP] | |||||

| 137.4 | 137.5 | 137.2 | 137.7 | 137.2 |

| 5.28 | 5.29 | 5.28 | 5.30 | 5.28 |

Notes: *** p-value < 0.01, * p-value < 0.1. t statistics in parentheses. MWTP denotes magnitude of WTP.

References

- Abdullah, S. M. M. B., Haji Othman, M. S. B., Zakaria, N. B., Ya’acob, F. F. B., & Alpandi, R. M. B. (2024). Assessing tourists’ Willingness to pay for community-based ecotourism: Enhancing sustainability and local involvement. Information Management and Business Review, 16(3(I)S), 359–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anindhita, T. A., Zielinski, S., Milanes, C. B., & Ahn, Y. (2024). The protection of natural and cultural landscapes through community-based tourism: The case of the indigenous Kamoro tribe in West Papua, Indonesia. Land, 13(8), 1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrow, K., Solow, R., Portney, P. R., Leamer, E. E., Radner, R., & Schuman, H. (1993). Report of the NOAA panel on contingent valuation. Federal Register, 58(10), 4601–4614. [Google Scholar]

- Baloch, Q. B., Shah, S. N., Iqbal, N., Sheeraz, M., Asadullah, M., Mahar, S., & Khan, A. U. (2023). Impact of tourism development upon environmental sustainability: A suggested framework for sustainable ecotourism. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 30(3), 5917–5930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Báez-Montenegro, A., Bedate, A. M., Herrero, L. C., & Sanz, J. Á. (2012). Inhabitants’ willingness to pay for cultural heritage: A case study in valdivia, chile, using contingent valuation. Journal of Applied Economics, 15(2), 235–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boronat-Navarro, M., & Pérez-Aranda, J. A. (2020). Analyzing willingness to pay more to stay in a sustainable hotel. Sustainability, 12(9), 3730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukas, N. (2008). Cultural tourism, young people and destination perception: A case study of Delphi, Greece [Ph.D. thesis, University of Exeter]; pp. 1–406. [Google Scholar]

- Champ, P. A., Boyle, K. J., & Brown, T. C. (2017). A primer on nonmarket valuation (P. A. Champ, K. J. Boyle, & T. C. Brown, Eds.; Vol. 13). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Q., Chen, J., & Zheng, Y. (2025). Assessing the impact of community-based homestay experiences on tourist loyalty in sustainable rural tourism development. Scientific Reports, 15(1), 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dao, M. A., & Vu, N. (2018). Phát triển du lịch cộng đồng ở Việt Nam—Nghiên cứu điển hình tại Làng cổ Đường Lâm và Bản Lác [Developing community-based tourism in Vietnam—A case study of Duong Lam ancient village and Lac village]. Tạp Chí Khoa Học Kinh Tế [Journal of Economic Science], 6(01), 100–112. [Google Scholar]

- Dardanoni, V., & Guerriero, C. (2021). Young people’ s willingness to pay for environmental protection. Ecological Economics, 179, 106853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Araújo, A. F., Marques, M. I. A., Candeias, M. T. R., & Vieira, A. L. (2022). Willingness to pay for sustainable destinations: A structural approach. Sustainabilityss, 14(5), 2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decision 147/QĐ-TTg. (2020). Available online: https://english.luatvietnam.vn (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- de Farias, E., Silva, A. S., & da Costa, M. F. (2022). Factors that influence tourists for ecogastronomic destinations. Gestão & Regionalidade, 38(113), 113–130. [Google Scholar]

- Denman, R. (2001). Guidelines for community-based ecotourism development. In WWF international (Issue July). Available online: https://wwf.panda.org/wwf_news/?12002 (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Dodds, R., Ali, A., & Galaski, K. (2018). Mobilizing knowledge: Determining key elements for success and pitfalls in developing community-based tourism. Current Issues in Tourism, 21(13), 1547–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, K., & Zeng, X. (2018). Public willingness to pay for urban smog mitigation and its determinants: A case study of Beijing, China. Atmospheric Environment, 173, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezeh, P. C., & Dube, K. (2024). Willingness to pay in tourism and its influence on sustainability. Sustainability, 16(23), 630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawcett, T. (2006). An introduction to ROC analysis. Pattern Recognition Letters, 27(8), 861–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischbach, E., Sparks, E., Hudson, K., Lio, S., & Englebretson, E. (2022). Consumer concern and willingness to pay for plastic alternatives in food service. Sustainability, 14(10), 5992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gall-Ely, M. L. (2009). Definition, measurement and determinants of the consumer’s willingness to pay: A critical synthesis and avenues for further research. Recherche et Applications En Marketing (English Edition), 24(2), 91–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, M. N., Muñoz-Gallego, P. A., & González-Benito, Ó. (2017). Tourists’ willingness to pay for an accommodation: The effect of eWOM and internal reference price. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 62, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herranz, J., Jackson, M. R., Kabwasa-Green, F., & Swenson, D. (2004). Community based cultural tourism: Findings from the US. Sustainable Tourism, 9, 191–198. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, L. A. (2025). Community-based tourism: A catalyst for achieving the United Nations sustainable development goals one and eight. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(1), 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, T. B., & Getz, D. (1995). Collaboration theory and community tourism planning. Annals of Tourism Research, 22(1), 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, G., Witten, D., Hastie, T., & Tibshirani, R. (2021). An introduction to statistical learning. Springer US. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khuc, V. Q. (2023). Culture tower (pp. 1–11). Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4559667 (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Khuc, V. Q., Tran, M., Nguyen, A. T., Hoang, K. L., Dang, T., Nguyen, T. M. H., & Tran, D. T. (2024). Closing nature connectedness to foster environmental culture: Investigating urban residents’ utilization and contribution to parks in Vietnam. Discover Sustainability, 5(1), 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koumoutsea, A., Boufounou, P., & Mergos, G. (2023). Evaluating the creative economy applying the contingent valuation method: A case study on the Greek cultural heritage festival. Sustainability, 15(23), 16441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law on Tourism. (2017). Available online: https://thuvienphapluat.vn/ (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Liang, A. R.-D., Tung, W., Wang, T.-S., & Hui, V. W. (2023). The use of co-creation within the community-based tourism experiences. Tourism Management Perspectives, 48, 101157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, T.-Y., Leong, C.-M., Lim, L. T.-K., Lim, B. C.-Y., Lim, R. T.-H., & Heng, K.-S. (2023). Young adult tourists’ intentions to visit rural community-based homestays. Young Consumers: Insight and Ideas for Responsible Marketers, 24(5), 540–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loan, K. (2023). Viet Nam Tourism marketing strategy for 2030 launched. Government News. Available online: https://en.baochinhphu.vn/ (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Ma, T., Min, Q., Xu, K., & Sang, W. (2021). Resident willingness to pay for ecotourism resources and associated factors in Sanjiangyuan National Park, China. Journal of Resources and Ecology, 12(5), 693–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masiero, L., Heo, C. Y., & Pan, B. (2015). Determining guests’ willingness to pay for hotel room attributes with a discrete choice model. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 49(6), 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, F., & Nadarajah, R. (2023). Valuing visitor’s willingness to pay for green tourism conservation: A case study of Bukit Larut Forest Recreation Area, Perak, Malaysia. Sustainable Environment, 9(1), 2188767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutuku, J., Yanotti, M., Tinch, D., & Hatton MacDonald, D. (2022). Willingness to pay for cleaning up beach litter: A meta-analysis. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 185, 114220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, K. M., Partelow, S., Stäbler, M., Graci, S., & Fujitani, M. (2021). Tourist willingness to pay for local green hotel certification. PLoS ONE, 16(2), e0245953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, T. H., & Creutz, S. (2022). Assessing the sustainability of community-based tourism: A case study in rural areas of Hoi An, Vietnam. Cogent Social Sciences, 8(1), 2116812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, T. H., Tournois, N., Dinh, T. L. T., Chu, M. T., & Phan, C. S. (2024). Sustainable community-based tourism development: Capacity building for community; the case study in Cam Kim, Hoi An, Vietnam. Journal of Sustainability Research, 6(2), e240022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H. M., Nguyen, T. H., Phan, C. A., & Matsui, Y. (2015). Service quality and customer satisfaction: A case study of hotel industry in Vietnam. Asian Social Science, 11(10), 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Q. N., Mai, V. N., & Hoang, T. H. L. (2024). Explaining tourist satisfaction with community-based tourism in the Mekong Delta region, Vietnam. GeoJournal of Tourism and Geosites, 56(4), 1661–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oka, I. M. D., Murni, N. G. N. S., & Mecha, I. P. S. (2021). The community-based tourism at the tourist village in the local people’s perspective. Geojournal of Tourism and Geosites, 38(4), 977–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oltean, F. D., Curta, P. A., Nagy, B., Huseyn, A., & Gabor, M. R. (2025). Changes in tourists’ perceptions of Community-Based Ecotourism (CBET) after COVID-19 pandemic: A study on the country of origin and economic development level. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 14(4), 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ondieki, E. B., Amwata, D. A., Nyariki, D. M., & Bulitia, G. M. (2023). Tourists choice of destinations and willingness to pay for environmental conservation. Research Article Journal of Tourism & Hospitality, 12(5), 1000530–1000531. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega-Rodríguez, C., Vena-Oya, J., Barreal, J., & Józefowicz, B. (2024). How to finance sustainable tourism: Factors influencing the attitude and willingness to pay green taxes among university students. Green Finance, 6(4), 649–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panwanitdumrong, K., & Chen, C. L. (2022). Are tourists willing to pay for a marine litter-free coastal attraction to achieve tourism sustainability? Case study of Libong Island, Thailand. Sustainability, 14(8), 4808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasanchay, K., & Schott, C. (2021). Community-based tourism homestays’ capacity to advance the sustainable development goals: A holistic sustainable livelihood perspective. Tourism Management Perspectives, 37, 100784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.-Y. J., Lee, K. L., & Ingersoll, G. M. (2002). An introduction to logistic regression analysis and reporting. The Journal of Educational Research, 96(1), 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, C. A., Nguyen, T. H., & Nguyen, H. M. (2013). Nghiên cứu các mô hình đánh giá chất lượng dịch vụ [Review of service quality assessment models]. Tạp Chí Khoa Học ĐHQGHN, Kinh Tế và Kinh Doanh [VNU Journal of Economics and Business], 29, 11–22. [Google Scholar]

- Schönherr, S., & Pikkemaat, B. (2024). Young peoples’ environmentally sustainable tourism attitude and responsible behavioral intention. Tourism Review, 79(4), 939–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H., Zheng, X., Lee, C., & Jia, J. (2023). Tourists’ willingness to pay for the non-use values of ecotourism resources in a national forest park. Journal of Resources and Ecology, 14(2), 331–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanciu, M., Popescu, A., Sava, C., Moise, G., Nistoreanu, B. G., Rodzik, J., & Bratu, I. A. (2022). Youth’s perception toward ecotourism as a possible model for sustainable use of local tourism resources. Frontiers in Environmental Science, 10, 940957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suyatna, H., Indroyono, P., Yuda, T. K., & Firdaus, R. S. M. (2024). How community-based tourism improves community welfare? A practical case study of ‘Governing the Commons’ in Rural Nglanggeran, Indonesia. The International Journal of Community and Social Development, 6(1), 77–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thao, H. T. P., & Bakucz, M. (2024). Good governance and tourism development in Vietnam: Looking back at the past three decades (1990–2023). Cogent Business & Management, 11(1), 2407048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T. H., Nguyen, T. B. H., Nguyen, D. M., Luu, Q. V., Nguyen, H. H., Phung, T. T., Ta, T. N., & Bui, T. S. (2018). Đánh giá tác động của hoạt động du lịch sinh thái tới môi trường tự nhiên và xã hội tại Bản Lác, xã Chiềng Châu, huyện Mai Châu, tỉnh Hòa Bình [Assessing impacts of ecotourism activities to natural and social environment at Lac village, Chieng Chau commun. Tạp Chí Khoa Học và Công Nghệ Lâm Nghiệp [Journal of Forestry Science and Technology], 1, 113–122. [Google Scholar]