How Do Behavioral Factors, Past Experience, and Emotional Events Influence Tourist Continuance Intention in Halal Tourism?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Tourist Continuance Intention

2.2. Sustainable Tourist Citizenship Behavior and Tourist Continuance Intention

2.3. Theory of Planned Behavior and Tourist Continuance Intention

2.4. Perceived Behavioral Control and Sustainable Tourist Citizenship Behavior (STCB)

2.5. Subjective Norm and Perceived Behavioral Control

2.6. Attitude and Perceived Behavioral Control

2.7. Tourist Emotional Events and Subjective Norms

2.8. Tourist Emotional Events and Attitude

2.9. Past Halal Experience and Perceived Behavioral Control

2.10. Past Halal Experience and Attitude

3. Research Method

3.1. Sampling and Data Collection

3.2. Measurement

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive of Respondent

4.2. Preliminary Test

4.3. Validity and Reliability Tests

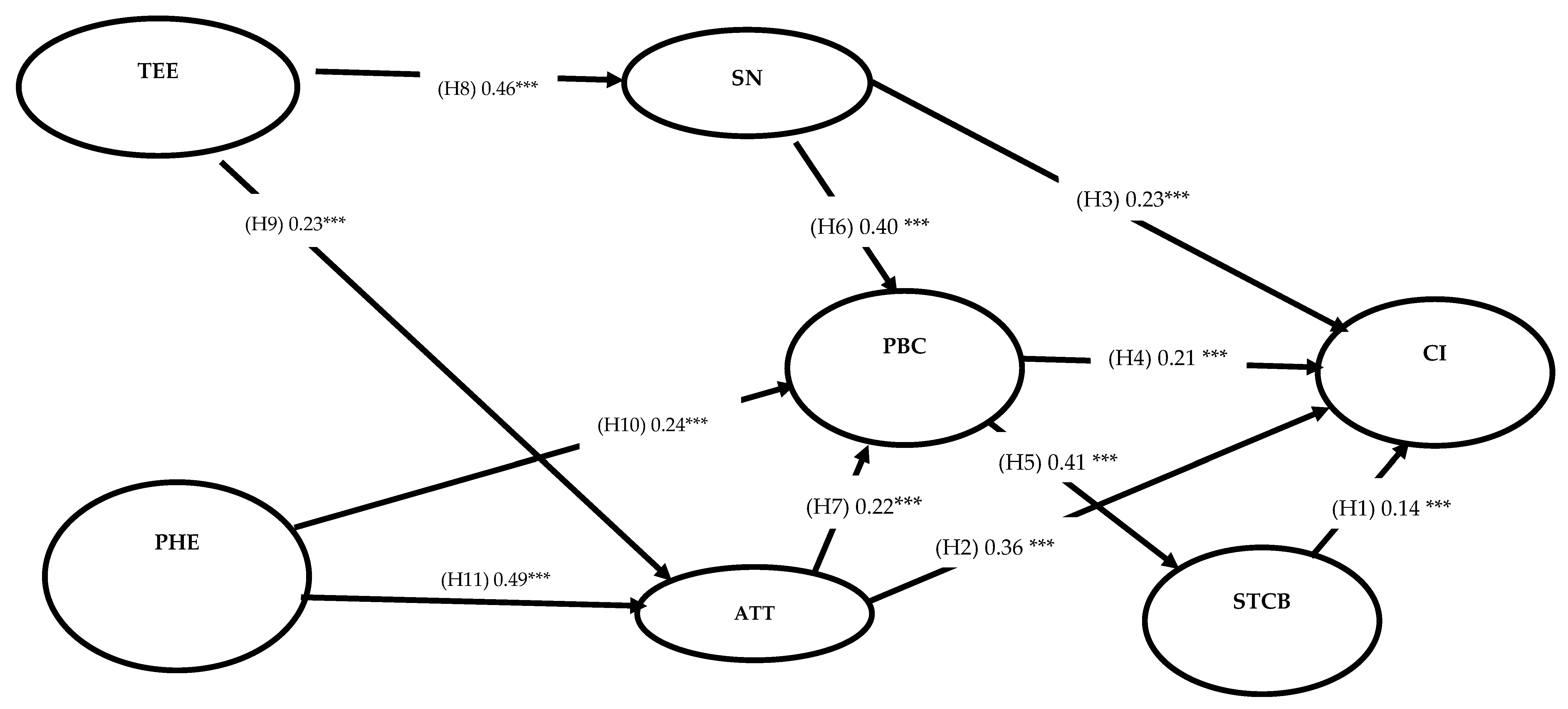

4.4. Structural Model and Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Contribution

6.2. Managerial Implications

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahn, J., Back, K.-J., Barišić, P., & Lee, C.-K. (2020). Co-creation and integrated resort experience in Croatia: The application of service-dominant logic. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 17, 100443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. (2020). The theory of planned behavior: Frequently asked questions. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, 2, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida-Santana, A., & Moreno-Gil, S. (2018). Understanding tourism loyalty: Horizontal vs. destination loyalty. Tourism Management, 65, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battour, M., & Ismail, M. N. (2016). Halal tourism: Concepts, practises, challenges and future. Tourism Management Perspectives, 19, 150–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhutto, M. Y., Ertz, M., Soomro, Y. A., Khan, M. a. A., & Ali, W. (2023). Adoption of halal cosmetics: Extending the theory of planned behavior with moderating role of halal literacy (evidence from Pakistan). Journal of Islamic Marketing, 14, 1488–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cossío-Silva, F., Revilla-Camacho, M., & Vega-Vázquez, M. (2019). The tourist loyalty index: A new indicator for measuring tourist destination loyalty? Journal of Innovation & Knowledge, 4(2), 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delpechitre, D., Beeler-Connelly, L. L., & Chaker, N. N. (2018). Customer value co-creation behavior: A dyadic exploration of the influence of salesperson emotional intelligence on customer participation and citizenship behavior. Journal of Business Research, 92, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, C. D. (2022). Psychological distress related to COVID-19 in healthy public (CORPD): A statistical method for assessing the validation of scale. MethodsX, 9, 101645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eid, R., & El-Gohary, H. (2014). Muslim tourist perceived value in the hospitality and tourism industry. Journal of Travel Research, 54, 774–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eid, R., & El-Gohary, H. (2015). The role of Islamic religiosity on the relationship between perceived value and tourist satisfaction. Tourism Management, 46, 477–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govaerts, F., & Ottar Olsen, S. (2023). Consumers’ values, attitudes and behaviours towards consuming seaweed food products: The effects of perceived naturalness, uniqueness, and behavioural control. Food Research International, 165, 112417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groth, M., Wu, Y., Nguyen, H., & Johson, A. (2019). The moment of truth: A review, synthesis, and research agenda for the customer service experience. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 6, 83–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis. Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Halimi, F. F., Gabarre, S., Rahi, S., Al-Gasawneh, J. A., & Ngah, A. H. (2021). Modelling Muslims’ revisit intention of non-halal certified restaurants in Malaysia. Journal of Islamic Marketing. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H., Hsu, L.-T., & Sheu, C. (2010). Application of the theory of planned behavior to green hotel choice: Testing the effect of environmental friendly activities. Tourism Management, 31, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X., Dai, S., & Xu, H. (2020). Predicting tourists’ health risk preventative behaviour and travelling satisfaction in Tibet: Combining the theory of planned behaviour and health belief model. Tourism Management Perspectives, 33, 100589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurst, P., Ng, P. Y., Under, L., & Fuggle, C. (2024). Dietary supplement use is related to doping intention via doping attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control. Performance Enhancement & Health, 12, 100278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irahmafitria, F., Suryadi, K., Oktadiana, H., Putro, H. P. H., & Rosyidie, A. (2021). Applying knowledge, social concern and perceived risk in planned behavior theory for tourism in the COVID-19 pandemic. Tourism Review, 76, 809–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo-Yusta, A., Martínez–Ruiz, M. P., & Pérez–Villarreal, H. H. (2022). Studying the impact of food values, subjective norm and brand love on behavioral loyalty. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 65, 102885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, I., Zaman, U., Ha, H., & Nawaz, S. (2025). Assessing the interplay of trust dynamics, personalization, ethical AI practices, and tourist behavior in the adoption of AI-driven smart tourism technologies. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 11, 100455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J., Lee, C.-K., & Choi, Y. (2011). Examining the role of emotional and functional values in festival evaluation. Journal of Travel Research, 50, 685–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J., Shin, H., & Kang, J. (2024). Investigating the managerial effects of workcations (work(plus)vacations) on digital nomad employees: Workcation satisfaction, work engagement, innovation behavior, intention to stay, and revisit intention. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 59, 324–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastercard-CrescentRating. (2024). Global Muslim Travel (GMTI) report 2024. CrescentRating. Available online: https://www.crescentrating.com/reports/global-muslim-travel-index-2024.html (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Meng, B., & Cui, M. (2020). The role of co-creation experience in forming tourists’ revisit intention to home-based accommodation: Extending the theory of planned behavior. Tourism Management Perspectives, 33, 100581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na-Nan, K., Kanthong, S., & Joungtrakul, J. (2021). An empirical study on the model of self-efficacy and organizational citizenship behavior transmitted through employee engagement, organizational commitment and job satisfaction in the Thai automobile parts manufacturing industry. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 7, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H. S. (2024). The impact of value co-creation behavior on customer loyalty in the service domain. Heliyon, 10, e30278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, K. T. T., Murphy, L., & Chen, T. (2025). The influence of host-tourist interaction on visitor perception of long-term ethnic tourism outcomes: Considering a complexity of physical settings. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 62, 304–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieves-Pavón, S., López-Mosquera, N., & Jiménez-Naranjo, H. (2024). The role emotions play in loyalty and WOM intention in a Smart Tourism Destination Management. Cities, 145, 104681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahrudin, P., Chen, C.-T., & Liu, L.-W. (2021). A modified theory of planned behavioral: A case of tourist intention to visit a destination post pandemic COVID-19 in Indonesia. Heliyon, 7, e08230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrisia, D., Abror, A., Engriani, Y., Omar, M. W., Yasri, Y., Shabbir, H., Gaffar, V., Abdullah, A.-R., Rahmiati, R., Thabrani, G., & Fitria, Y. (2025). Halal literacy, health consciousness, past product quality experience and repurchase intention of halal culinary product. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 16, 1311–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J., Modi, A., & Patel, J. (2016). Predicting green product consumption using theory of planned behavior and reasoned action. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 29, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Sanchez, C., Torres-Moraga, E., Sancho-Esper, F., & Casado-Díaz, A. B. (2025). Prosocial disposition shaping tourist citizenship behavior: Toward destination patronage intention. Tourism Management Perspectives, 55, 101334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawaneh, I. A., Fan, L., & Sesay, B. (2024). Investigating the influence of residents’ attitudes, perceptions of risk, and subjective norms on their willingness to engage in flood prevention efforts in Freetown, Sierra Leone. Nature-Based Solutions, 6, 100143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhartanto, D., Gan, C., Andrianto, T., Ismail, T. a. T., & Wibisono, N. (2021). Holistic tourist experience in halal tourism evidence from Indonesian domestic tourists. Tourism Management Perspectives, 40, 100884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susanto, K. C., Prasetyo, Y. T., Benito, O. P., Liao, J.-H., Cahigas, M. M. L., Nadlifatin, R., & Gumasing, M. J. J. (2024). Investigating factors influencing the intention to revisit Mount Semeru during post 2022 volcanic eruption: Integration theory of planned behavior and destination image theory. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 107, 104470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajeddini, K., Mostafa Rasoolimanesh, S., Chathurika Gamage, T., & Martin, E. (2021). Exploring the visitors’ decision-making process for Airbnb and hotel accommodations using value-attitude-behavior and theory of planned behavior. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 96, 102950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Moraga, E., Rodriguez-Sanchez, C., Alonso-Dos-Santos, M., & Vidal, A. (2024). Tourscape role in tourist destination sustainability: A path towards revisit. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 31, 100863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, S., & Tung, V. W. S. (2022). Understanding residents’ attitudes towards tourists: Connecting stereotypes, emotions and behaviours. Tourism Management, 89, 104435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, L. T., Rajendran, D., Rowley, C., & Khai, D. C. (2019). Customer value co-creation in the business-to-business tourism context: The roles of corporate social responsibility and customer empowering behaviors. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 39, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Tonder, E., Fullerton, S., De Beer, L. T., & Saunders, S. G. (2023). Social and personal factors influencing green customer citizenship behaviours: The role of subjective norm, internal values and attitudes. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 71, 103190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C., & Huang, X. (2025). Beyond the call of duty: Effects of school learning culture, teacher self-efficacy, and informal learning on organizational citizenship behavior. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 85, 101459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WYSETC. (2017). Countries compete for Muslim tourism dollars [Online]. WYSE Travel Confederation. Available online: https://www.wysetc.org/2017/06/countries-compete-for-muslim-tourism-dollars/ (accessed on 2 June 2018).

- Yao, Y., Wang, G., Ren, L., & Qiu, H. (2023). Exploring tourist citizenship behavior in wellness tourism destinations: The role of recovery perception and psychological ownership. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 55, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, E., & Gürlek Kisacik, Ö. (2025). Medical device-related pressure injuries: The mediating role of attitude in the relationship between ICU nurses’ knowledge levels and self-efficacy. Journal of Tissue Viability, 34, 100843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zailani, S., Ali, S. M., Iranmanesh, M., Moghavvemi, S., & Musa, G. (2016). Predicting Muslim medical tourists’ satisfaction with Malaysian Islamic friendly hospitals. Tourism Management, 57, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G., Liu, Y., Hu, J., & Cao, X. (2023). The effect of tourist-to-tourist interaction on tourists’ behavior: The mediating effects of positive emotions and memorable tourism experiences. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 55, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | Items | Loading | A | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sustainable Tourist Citizenship Behavior (STCB) | 0.885 | 0.909 | 0.769 | ||

| I assist other tourists if they need my help about environment | 0.867 | ||||

| I help other tourists if they seem to have environmental problems | 0.889 | ||||

| I teach other tourists to use the service correctly and environmentally friendly | 0.873 | ||||

| Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC) | 0.853 | 0.911 | 0.772 | ||

| I can afford to visit halal destination, even if slightly expensive. | 0.880 | ||||

| Visiting or not visiting halal destination is solely my decision | 0.873 | ||||

| If I want to visit a tourist destination, I will visit halal destination | 0.884 | ||||

| Attitude (ATT) | 0.905 | 0.941 | 0.841 | ||

| Choosing halal destination is a good idea | 0.902 | ||||

| I like to choose halal destination | 0.920 | ||||

| Visiting halal destination is pleasant | 0.928 | ||||

| Subjective Norm (SN) | 0.833 | 0.923 | 0.857 | ||

| My family thinks that I should visit halal destination | 0.929 | ||||

| Most people I value would visit halal destination | 0.922 | ||||

| Tourist Emotional Event (TEE) | 0.885 | 0.909 | 0.626 | ||

| I interacted well with my companions in the destination | 0.831 | ||||

| I felt satisfied with being part of my companions. | 0.854 | ||||

| My companions made my time there more enjoyable. | 0.855 | ||||

| I interacted well with other tourists at the destination. | 0.762 | ||||

| I developed friendships with other tourists whom I met at the destination. | 0.711 | ||||

| I felt satisfied with being there with other tourists at the destination. | 0.720 | ||||

| Past Halal Experience (PHE) | 0.880 | 0.909 | 0.624 | ||

| Availability of prayer room for men/women | 0.757 | ||||

| Halal facilities in tourist locations | 0.771 | ||||

| Certification of Halal food | 0.797 | ||||

| Healthiness of Halal food and beverage | 0.820 | ||||

| Services offered conformity to Islamic law | 0.806 | ||||

| Appropriateness of staff dressing places are good. | 0.789 | ||||

| Continuance Intention (CI) | 0.888 | 0.931 | 0.817 | ||

| In the future, I would like to revisit this halal destination. | 0.894 | ||||

| This halal destination is my first choice in the future. | 0.917 | ||||

| The probability that I will consider revisit this destination is high | 0.901 |

| Construct | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATT | |||||||

| CI | 0.791 | ||||||

| PBC | 0.733 | 0.750 | |||||

| PHE | 0.702 | 0.705 | 0.728 | ||||

| SN | 0.780 | 0.769 | 0.833 | 0.732 | |||

| STCB | 0.506 | 0.515 | 0.465 | 0.541 | 0.381 | ||

| TEE | 0.551 | 0.518 | 0.518 | 0.665 | 0.514 | 0.522 |

| Hypothesis | Coefficient | SD | p Value | Hypothesis Verdict | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | STCB → CI | 0.14 | 0.046 | *** | Supported |

| H2 | ATT → CI | 0.36 | 0.054 | *** | Supported |

| H3 | SN → CI | 0.23 | 0.052 | *** | Supported |

| H4 | PBC → CI | 0.21 | 0.050 | *** | Supported |

| H5 | PBC → STCB | 0.41 | 0.049 | *** | Supported |

| H6 | SN → PBC | 0.40 | 0.059 | *** | Supported |

| H7 | ATT → PBC | 0.22 | 0.050 | *** | Supported |

| H8 | TEE → SN | 0.46 | 0.044 | *** | Supported |

| H9 | TEE → ATT | 0.23 | 0.044 | *** | Supported |

| H10 | PHE → PBC | 0.24 | 0.046 | *** | Supported |

| H11 | PHE → ATT | 0.49 | 0.045 | *** | Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abror, A.; Patrisia, D.; Engriani, Y.; Firman, F.; Linda, M.R.; Gaffar, V.; Suhud, U.; Boonkaew, S.; Aujirapongpan, S. How Do Behavioral Factors, Past Experience, and Emotional Events Influence Tourist Continuance Intention in Halal Tourism? Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 217. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6040217

Abror A, Patrisia D, Engriani Y, Firman F, Linda MR, Gaffar V, Suhud U, Boonkaew S, Aujirapongpan S. How Do Behavioral Factors, Past Experience, and Emotional Events Influence Tourist Continuance Intention in Halal Tourism? Tourism and Hospitality. 2025; 6(4):217. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6040217

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbror, Abror, Dina Patrisia, Yunita Engriani, Firman Firman, Muthia Roza Linda, Vanessa Gaffar, Usep Suhud, Sunthorn Boonkaew, and Somnuk Aujirapongpan. 2025. "How Do Behavioral Factors, Past Experience, and Emotional Events Influence Tourist Continuance Intention in Halal Tourism?" Tourism and Hospitality 6, no. 4: 217. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6040217

APA StyleAbror, A., Patrisia, D., Engriani, Y., Firman, F., Linda, M. R., Gaffar, V., Suhud, U., Boonkaew, S., & Aujirapongpan, S. (2025). How Do Behavioral Factors, Past Experience, and Emotional Events Influence Tourist Continuance Intention in Halal Tourism? Tourism and Hospitality, 6(4), 217. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6040217