From Malls to Markets: What Makes Shopping Irresistible for Chinese Tourists?

Abstract

1. Introduction

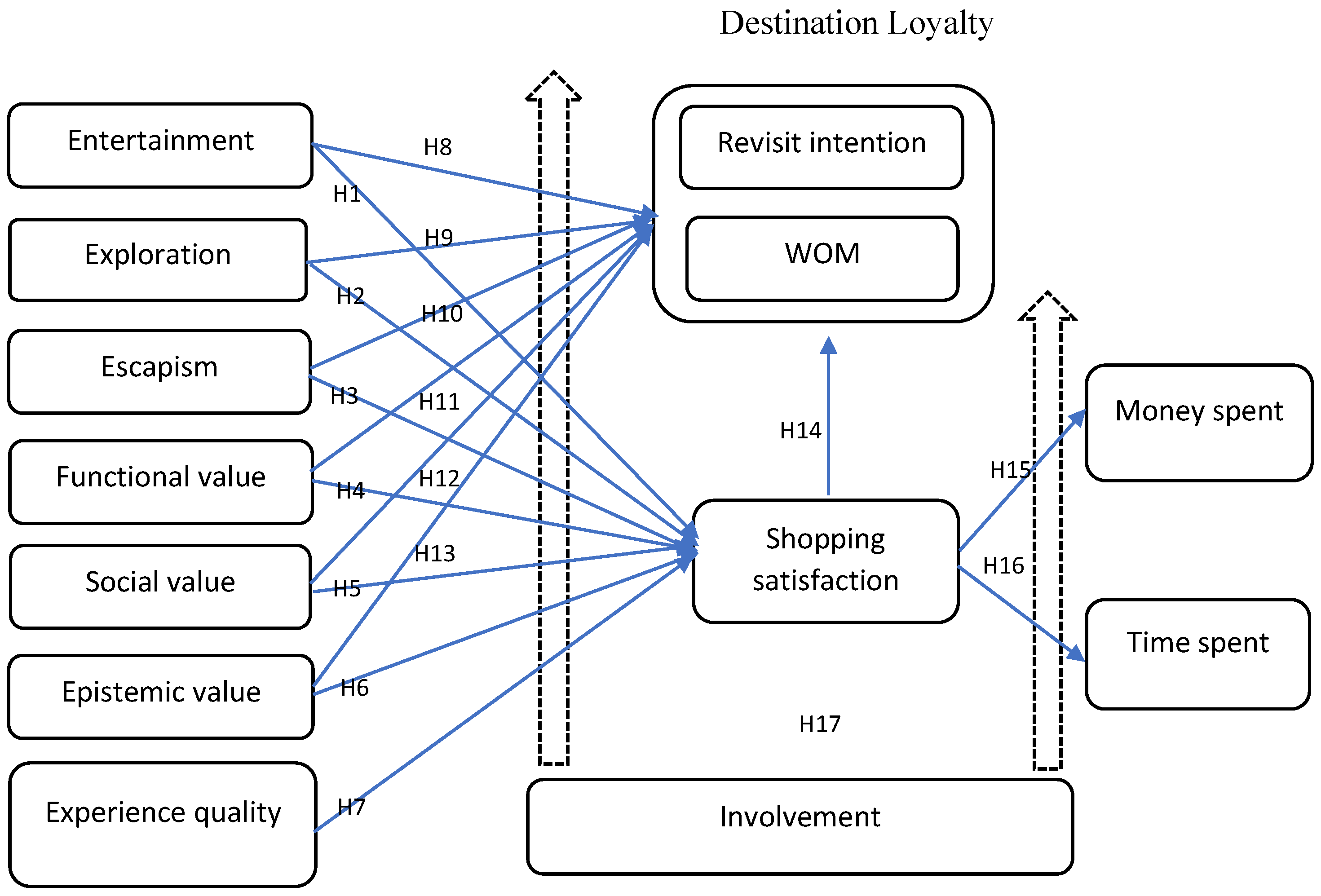

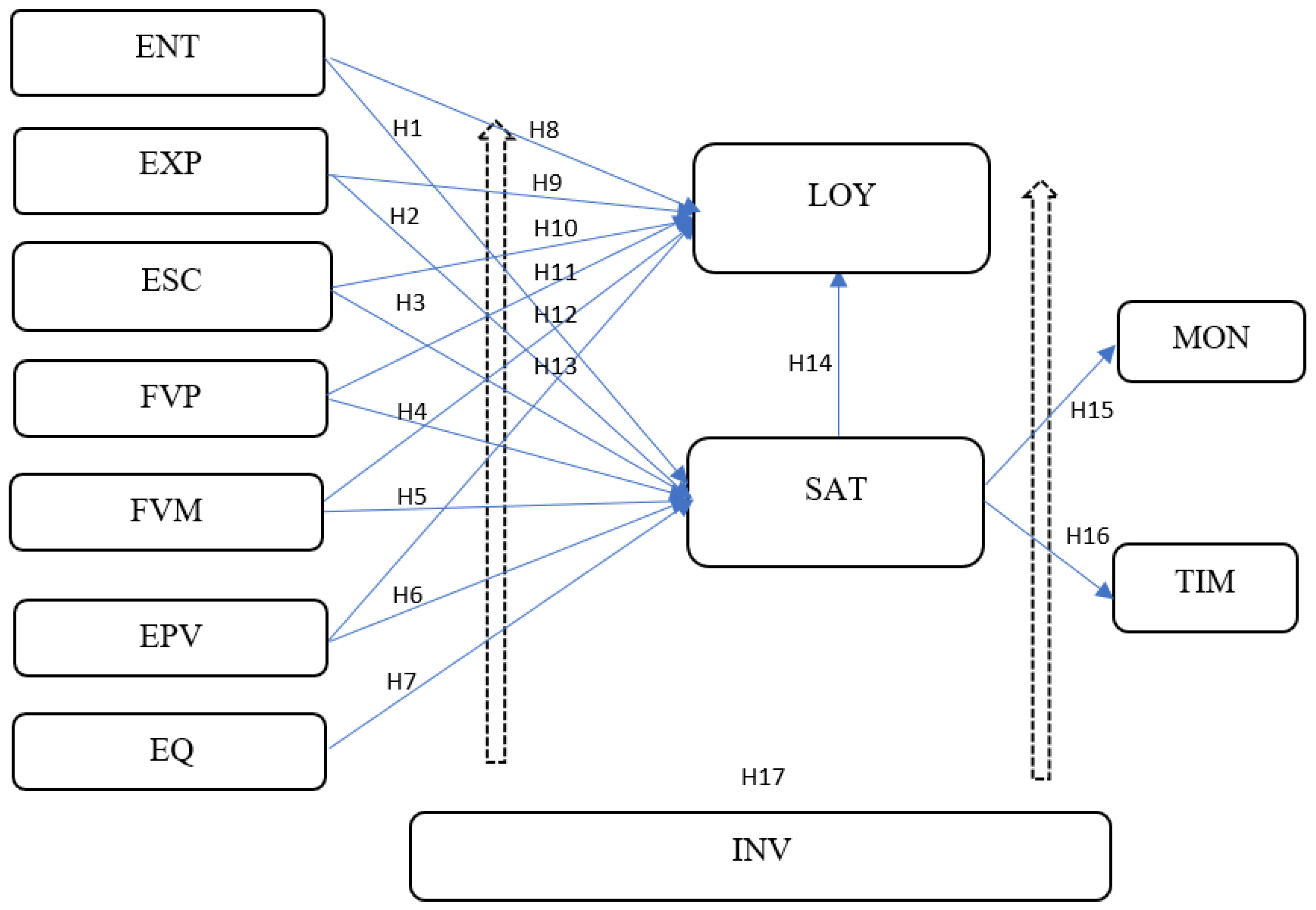

2. Literature Review

2.1. Shopping Tourism

2.2. Value and Value Dimensionality

2.3. Hedonic Value and Shopping Satisfaction

2.4. Functional Value and Shopping Satisfaction

2.5. Social Value and Shopping Satisfaction

2.6. Epistemic Value and Shopping Satisfaction

2.7. Experience Quality and Shopping Satisfaction

2.8. Shopping Values and Destination Loyalty

2.9. Shopping Satisfaction and Destination Loyalty

2.10. Shopping Satisfaction and Money and Time Spent

2.11. Moderating Effect of Shopping Involvement

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Data Collection and Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

4.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

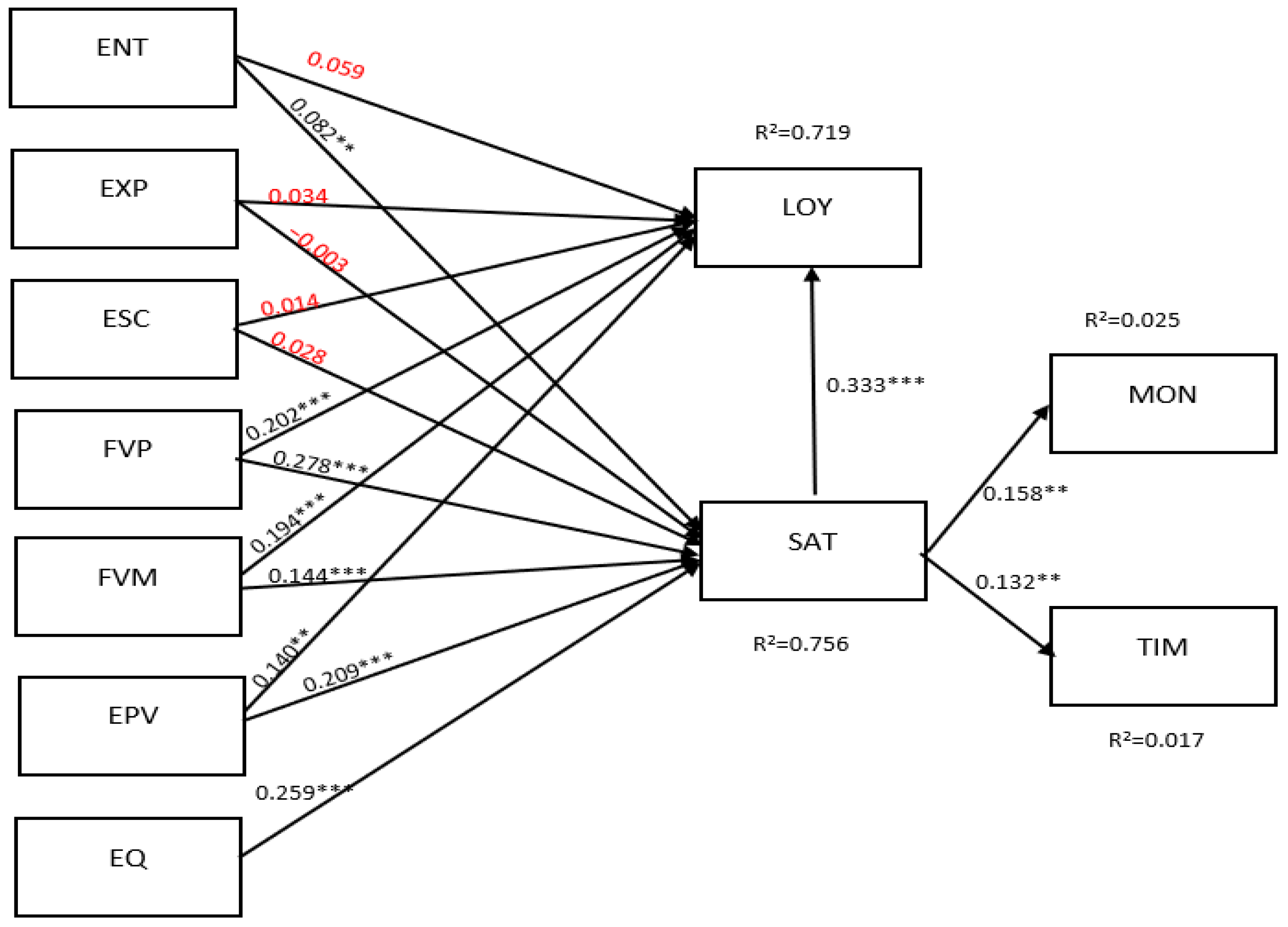

4.3. Path Analysis and Hypothesis Testing

- Shopping satisfaction predictors: entertainment (H1), functional value for performance (H4), functional value for money (H5), epistemic value (H6), and experience quality (H7).

- Destination loyalty predictors: functional value for performance (H11), functional value for money (H12), epistemic value (H13), and satisfaction (H14).

- Shopping impact: satisfaction significantly influenced money spent (H15) and time spent (H16).

4.4. Moderation Effect of Involvement

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Discussion

5.2. Theoretical Contributions

5.3. Practical Implications

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Gender | Percent | Education | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 46.7% | High school or less | 3.4% |

| Female | 52.5% | Some college/college diploma | 11.1% |

| Prefer not to say | 0.8% | Bachelor’s degree | 75.1% |

| Age | Percent | Some graduate/or graduate degree | 10.3% |

| 20 and younger | 2.7% | Occupation | Percent |

| 21–30 | 31.2% | Fully employed | 94.7% |

| 31–40 | 40.4% | Part time employed | 1.5% |

| 41–50 | 19.9% | Retires | 0.5% |

| 51–60 | 5.3% | Student/others | 3.3% |

| 61 add older | 0.5% | Times visited | Percent |

| Marital status | Percent | 1–3 times | 84.3% |

| Never married | 16.5% | 4–6 times | 10.9% |

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 0.7% | 7–10 times | 3.1% |

| Married/common-law partners | 82.8% | over 11 times | 1.7% |

| Others | 0.0% | Shopping list | Percent |

| Income | Percent | Yes | 59.8% |

| Under ¥49,999 | 0.0% | No | 40.2% |

| ¥50,000–¥99,999 | 4.1% | Nights stay | Percent |

| ¥100,000–¥199,999 | 19.9% | 2 nights | 7.3% |

| ¥200,000–¥299,999 | 32.9% | 3 nights | 20.1% |

| ¥300,000–¥399,999 | 20.3% | 4 nights | 21.5% |

| ¥400,000–¥499,999 | 12.3% | 5 nights | 24.5% |

| ¥500,000 or above | 10.5% | Over 5 nights | 26.6% |

Appendix B

| Factor/Items | Factor Loading | Other Values |

|---|---|---|

| Functional value for performance (4 items) | ||

| FVP1. Products purchased during the shopping trip in Japan had acceptable quality standard. | 0.743 | Eigenvalue: 9.540 Var. expl. (%): 13.63 Cronbach’s alpha:0.825 |

| FVP2. Products purchased during the shopping trip in Japan were well made. | 0.735 | |

| FVP3. Products purchased during the shopping trip in Japan had consistent quality. | 0.731 | |

| FVP4. Products purchased during the shopping trip in Japan had consistent performance. | 0.540 | |

| Functional value for money (4 items) | ||

| FVM1. The shopping trip in Japan was economical. | 0.805 | Eigenvalue: 1.588 Var. expl. (%): 12.45 Cronbach’s alpha: 0.857 |

| FVM2. The costs of a shopping trip in Japan were reasonable. | 0.678 | |

| FVM3. The shopping trip in Japan offered better value for money than other trips. | 0.634 | |

| FVM4. The shopping trip in Japan had a good value for money. | 0.598 | |

| Entertainment (4 items) | ||

| ENT1. I liked the shopping itself, not only for the items I bought. | 0.727 | Eigenvalue: 1.319 Var. expl. (%): 11.93 Cronbach’s alpha: 0.778 |

| ENT2. I enjoyed the entertaining environment (such as music, aroma, light) provided in the stores I visited. | 0.721 | |

| ENT3. The entertaining environment in the store (ex. Music, aroma, lights, etc.) I visited made shopping process fun. | 0.669 | |

| ENT4. When I was shopping, I enjoyed the time because I could shop without thinking. | 0.587 | |

| Epistemic Value (4 items) | ||

| EPV1. I enjoyed looking around when shopping to keep up with the newest trends and fashion. | 0.720 | Eigenvalue: 1.022 Var. expl. (%): 11.02 Cronbach’s alpha: 0.837 |

| EPV2. I liked shopping at the destination to learn interesting ways of decoration, dressing models, using different colors together. | 0.663 | |

| EPV3. I went shopping to see what was interesting or innovative. | 0.662 | |

| EPV4. I liked to do shopping at the destination to get ideas about new trends, fashion, style, and products. | 0.558 | |

| Escapism (3 items) | ||

| ESC1. Shopping in Japan helped me escape from my work-related problems. | 0.806 | Eigenvalue: 1.015 Var. expl. (%): 10.76 Cronbach’s alpha: 0.796 |

| ESC2. I could forget my problems while shopping. | 0.750 | |

| ESC3. Shopping in Japan allowed me to escape from my worldly cares. | 0.707 | |

| Exploration (3 items) | ||

| EXP1. I felt shopping was an adventurous process. | 0.877 | Eigenvalue: 1.001 Var. expl. (%): 9.29 Cronbach’s alpha: 0.739 |

| EXP2. When shopping, I felt I was on an adventure. | 0.719 | |

| EXP3. To me, shopping was an adventure. | 0.645 | |

| Experience quality (4 items) | ||

| EQ1. I was confident with the employees’ expertise in the stores I visited. | 0.840 | Eigenvalue: 2.528 Var. expl. (%): 63.21 Cronbach’s alpha: 0.806 |

| EQ2. Japan provides a consistent shopping environment. | 0.795 | |

| EQ3. The employees in stores I visited treated me with respect. | 0.787 | |

| EQ4. I think my satisfaction with the products/services was the management’s most important concern. | 0.756 | |

| Shopping Satisfaction (5 items) | ||

| SAT1. Overall, I was satisfied with my recent shopping experience in Japan. | 0.845 | Eigenvalue: 3.211 Var. expl. (%): 64.22 Cronbach’s alpha: 0.857 |

| SAT2. My attitudes to my recent shopping experience in Japan were very positive. | 0.819 | |

| SAT3. Overall, the shopping experience in Japan was better than I expected. | 0.810 | |

| SAT4. I was satisfied with the services and products provided by the stores I visited. | 0.768 | |

| SAT5. Overall, I felt my recent trip to Japan has enriched me life. | 0.762 | |

| Destination loyalty (7 items) | ||

| LOY1. I intend to visit Japan in the future. | 0.836 | Eigenvalue: 4.444 Var. expl. (%): 63.49 Cronbach’s alpha: 0.903 |

| LOY2. I will speak about the shops that I visited in Japan with a sense of pride. | 0.827 | |

| LOY3. In the future, I would like to recommend Japan as a shopping destination to others. | 0.823 | |

| LOY4. In the future, when I want to shop overseas, I will consider Japan a destination choice. | 0.795 | |

| LOY5. I am likely to revisit Japan in the future. | 0.771 | |

| LOY6. I will talk to others about my recent shopping experience in Japan. | 0.762 | |

| LOY7. I will speak about the shops that I visited in Japan with a sense of pride. | 0.760 | |

References

- Afthanorhan, A., Ahmad, S., & Safee, S. (2014). Moderated mediation using covariance-based structural equation modeling with Amos graphic: Volunteerism program. Advances in Natural and Applied Sciences, 8(8), 108–116. [Google Scholar]

- Albayrak, T., Caber, M., & Comen, N. (2016). Tourist shopping: The relationships among shopping attributes, shopping value, and behavioral intention. Tourism Management Perspectives, 18, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegre, J., & Cladera, M. (2012). Tourist characteristics that influence shopping participation and expenditures. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 6(3), 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, M. J., & Reynolds, K. E. (2003). Hedonic shopping motivations. Journal of Retailing, 79(2), 77–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atulkar, S., & Kesari, B. (2017). Satisfaction, loyalty and repatronage intentions: Role of hedonic shopping values. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 39, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babin, B. J., Darden, W. R., & Griffin, M. (1994). Work and/or fun: Measuring hedonic and utilitarian shopping value. Journal of Consumer Research, 20(4), 644–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badu-Baiden, F., Otoo, F. E., & Kim, S. (2024). Understanding the role of the shopping experience in explaining tourists’ perceived value and behavioral intention in African markets. International Journal of Tourism Research, 26(5), e2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakırtaş, H., Bakırtaş, İ., & Çetin, M. A. (2015). Effects of utilitarian and hedonic shopping value and consumer satisfaction on consumer behavioral intentions. EGE Academic review, 15(1), 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baruca, A., & Zolfagharian, M. (2013). Cross-border shopping: Mexican shoppers in the US and American shoppers in Mexico. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 37(4), 360–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojanic, D. C. (2011). The impact of age and family life experiences on Mexican visitor shopping expenditures. Tourism Management, 32(2), 406–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, R. N., & Lemon, K. N. (1999). A dynamic model of customers’ usage of services: Usage as an antecedent and consequence of satisfaction. Journal of Marketing Research, 36(2), 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Y., Qiu, R. T., & Wen, L. (2024). A holistic model of tourists’ pro-sustainability shopping consumption: The role of tourist heterogeneity. Tourism Management, 105, 104976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K. C., Cheng, Y. S., Kuo, N. T., & Cheng, Y. H. (2025). Impacts of tourists’ shopping destination trust on post-visit behaviors: A loss aversion perspective. International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Administration, 26(1), 28–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chebat, J. C., Michon, R., Haj-Salem, N., & Oliveira, S. (2014). The effects of mall renovation on shopping values, satisfaction and spending behaviour. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Service, 21(4), 610–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. F., & Chen, F. S. (2010). Experience quality, perceived value, satisfaction and behavioral intentions for heritage tourists. Tourism Management, 31(1), 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. F., & Tsai, M. H. (2008). Perceived value, satisfaction, and loyalty of TV travel product shopping: Involvement as a moderator. Tourism Management, 29(6), 1166–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. S., & Gursoy, D. (2001). An investigation of tourists’ destination loyalty and preferences. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 13(2), 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T., Makara, D., Sean, C., McGinleya, S., & Cheng, J. (2019). Understanding the intention of tourist experience in the age of omni-channel shopping and its impact on shopping: Online shopping tendencies. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 8(5), 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W. W., Thatcher, J. B., Wright, R. T., & Steel, D. (2013). Controlling for common method variance in PLS analysis: The measured latent marker variable approach. In H. Abdi, W. W. Chin, V. Esposito Vinzi, G. Russolillo, & L. Trinchera (Eds.), New perspectives in partial least squares and related methods (pp. 231–239). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, M., Law, R., & Heo, C. Y. (2018). An investigation of the perceived value of shopping tourism. Journal of Travel Research, 57(7), 962–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, Y. S. (2015). Hedonic and utilitarian shopping values in airport shopping behavior. Journal of Air Transport Management, 49, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran, W. G. (1977). Sampling techniques. John Wiley & Sons Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, S. T., & Chancellor, H. C. (2009). Examining the festival attributes that impact visitor experience, satisfaction and re-visit intention. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 15(4), 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, A., Kozak, M., & Kim, S. (2018). Luxury shopping orientations of mainland Chinese tourists in Hong Kong: Their shopping destination. Tourism Economics, 24(1), 92–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, J. J., Brady, M. K., & Hult, G. T. M. (2000). Assessing the effects of quality, value, and customer satisfaction on consumer behavioral intentions in service environments. Journal of Retailing, 76(2), 193–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çavuşoğlu, S., Demirağ, B., & Durmaz, Y. (2021). Investigation of the effect of hedonic shopping value on discounted product purchasing. Review of International Business and Strategy, 31(3), 317–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Adly, M. I., & Eid, R. (2015). Measuring the perceived value of malls in a non-western context: The case of the UAE. International Journal Retail & Distribution Management, 43(9), 849–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Adly, M. I., & Eid, R. (2017). Dimensions of the perceived value of malls: Muslim shoppers’ perspective. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 45(1), 40–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, T., & Cruz, M. (2016). Dimensions and outcomes of experience quality in tourism: The case of Port wine cellars. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 31, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallarza, M. G., Gil Saura, I., & Arteaga Moreno, F. (2013). The quality-value-satisfaction-loyalty chain: Relationships and impacts. Tourism Review, 68(1), 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogoi, D. B. J. (2013). Antecedents of customer satisfaction in a retail store environment and its impact on time spent and impulse buying. International Journal of Management (IJM), 4(6), 21–35. [Google Scholar]

- Granados, J. C., Pérez, L. M., Pedraza-Rodríguez, J. A., & Gallarza, M. G. (2021). Revisiting the quality-value-satisfaction-loyalty chain for corporate customers in the travel agency sector. European Journal of Tourism Research, 27, 2711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2014). Multivariate data analysis: Pearson new international edition (7th ed.). Pearson Education Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 19(2), 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallak, R., Assaker, G., & El-Haddad, R. (2018). Re-examining the relationships among perceived quality, value, satisfaction, and destination loyalty: A higher-order structural model. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 24(2), 118–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H., Moon, H., & Kim, W. (2019). The influence of international tourists’ self-image congruity with a shopping place on their shopping experiences. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 41, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, T. Y., & Chuang, C. M. (2015). Independent travelling decision-making on B&B selection: Exploratory analysis of Chinese travellers to Taiwan. Anatolia, 26(3), 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S., Choi, H. C., Shen, Y., & Chang, H. S. (2021). Predicting behavioral intention: The mechanism from pretrip to posttrip. Tourism Analysis, 26(4), 279–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, K., Ren, L., & Qiu, H. (2021). Luxury shopping abroad: What do Chinese tourists look for? Tourism Management, 82, 104182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, J. (2015). The strengths and limitations of the statistical modeling of complex social phenomenon: Focusing on SEM, path analysis, or multiple regression models. International Journal of Economics and Management Engineering, 9(5), 1630–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H., Moscardo, G., & Murphy, L. (2017). Making sense of tourist shopping research: A critical review. Tourism Management, 62, 120–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M. A., Reynold, K. E., & Arnold, M. J. (2006). Hedonic and utilitarian shopping value: Investigating differential effects on retail outcomes. Journal of Business Research, 59(9), 974–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josiam, B., Kinley, T., & Kim, Y. K. (2005). Involvement and the tourist shoppers: Using the involvement construct to segment the American tourist shopper at the mall. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 11(2), 135–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J., & Park-Poaps, H. (2011). Motivational antecedents of social shopping for fashion and its contribution to shopping satisfaction. Clothing & Textiles Research Journal, 29(4), 331–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesari, B., & Atulkar, S. (2016). Satisfaction of mall shoppers: A study on perceived utilitarian and hedonic shopping values. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 31, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. K., Lee, M. Y., & Park, S. H. (2014). Shopping value orientation: Conceptualization and measurement. Journal of Business Research, 67, 2884–2890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinley, T. R., Josiam, B. M., & Lockett, F. (2010). Shopping behavior and the involvement construct. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal, 14(4), 562–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. S., & Choi, M. (2020). Examining the asymmetric effect of multi-shopping tourism attributes on overall shopping destination satisfaction. Journal of Travel Research, 59(2), 295–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y. H., & Chen, C. F. (2013). Passengers’ shopping motivations and commercial activities at airports–The moderating effects of time pressure and impulse buying tendency. Tourism Management, 36, 426–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKercher, B., & Guillet, B. D. (2011). Are tourists or markets destination loyal? Journal of Travel Research, 50(2), 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, D. P., & Min, J. (2010). Analyzing the relationship between dependent and independent variables in marketing: A comparison of multiple regression with path analysis. Innovative Marketing, 6(3), 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moharana, T. R., & Pattanaik, S. (2023). Post-pandemic revisit intentions: How shopping value and visit frequency matters. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 51(3), 386–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moharana, T. R., & Pradhan, D. (2020). Shopping value and patronage: When satisfaction and crowding count. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 38(2), 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, L., Moscardo, G., Benckendorff, P., & Pearce, P. (2011). Evaluating tourist satisfaction with the retail experience in a typical tourist shopping village. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 18(4), 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nippon. (2020, February 12). Chinese visitors spend ¥1.8 trillion in Japan in 2019. Available online: https://www.nippon.com/en/japan-data/h00646/chinese-visitors-spend-%C2%A51-8-trillion-in-japan-in-2019.html (accessed on 25 October 2024).

- Olsen, S. O. (2007). Repurchase loyalty: The role of involvement and satisfaction. Psychology & Marketing, 24(4), 315–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppermann, M. (2000). Tourism destination loyalty. Journal of Travel Research, 39(1), 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overby, J. W., & Lee, E. J. (2006). The effects of utilitarian and hedonic online shopping value on consumer preference and intentions. Journal of Business Research, 59(10–11), 1160–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, C., & Sanders, E. A. (2025). Shopping tourism: Its positive impact on mixed-use shopping mall communities (MUSMC). Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Cases. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rintamäki, T., Kanto, A., Kuusela, H., & Spence, M. T. (2006). Decomposing the value of department store shopping into utilitarian, hedonic and social dimensions: Evidence from Finland. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 34(1), 6–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabre. (2024). China unleashed: Key outbound Chinese travel insights for 2024. Available online: https://www.sabre.com/insights/china-unleashed-sabre-reveals-key-outbound-chinese-travel-insights-for-2024/ (accessed on 24 October 2024).

- Said, F. B., Meyer, N., Bahri-Ammari, N., & Soliman, M. (2024). Shopping tourism: A bibliometric review from 1979 to 2021. Journal of Tourism and Services, 15(28), 61–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangpikul, A. (2018). The effects of travel experience dimensions on tourist satisfaction and destination loyalty: The case of an island destination. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 12(1), 106–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, J. N., Newman, B. I., & Gross, B. L. (1991). Why we buy what we buy: A theory of consumption values. Journal of Business Research, 22(2), 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirakaya-Turk, E., Ekinci, Y., & Martin, D. (2015). The efficacy of shopping value in predicting destination loyalty. Journal of Business Research, 68(9), 1878–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolčić Jurdana, D., & Soldić Frleta, D. (2017). Satisfaction as a determinant of tourist expenditure. Current Issues in Tourism, 20(7), 691–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, H. K., & Lee, T. J. (2017). Tourists’ impulse buying behavior at duty-free shops: The moderating effects of time pressure and shopping involvement. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 34(3), 341–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhartanto, D., Dean, D., Amalia, F. A., Raman, A., & Nova, M. (2025). Enhancing tourist loyalty in predominantly Muslim destinations: Integrating religiosity and sense of community into the QVSL model. Advances in Hospitality and Tourism Research (AHTR), 13(2), 213–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhartanto, D., Ruhadi, & Triyuni, N. N. (2016). Tourist loyalty toward shopping destination: The role of shopping satisfaction and destination image. European Journal of Tourism Research, 13, 84–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T., Li, Y., & Tai, H. (2023). Different cultures, different images: A comparison between historic conservation area destination image choices of Chinese and Western tourists. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change, 21(1), 110–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Asahi Shimbun. (2024, April 30). Japan surpasses Thailand to top China’s golden week travel list. Available online: https://www.asahi.com/ajw/articles/15251108 (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- Timothy, D. J. (2005). Shopping tourism, retailing and leisure. Channel View. [Google Scholar]

- Toyama, M., & Yamada, Y. (2012). The relationships among tourist novelty, familiarity, satisfaction, and destination loyalty: Beyond the novelty-familiarity continuum. International Journal of Marketing Studies, 4(6), 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, N. K., Lee, L. Y. S., & Liu, C. K. (2014). Understanding the shopping motivation of mainland Chinese tourists in Hong Kong. Journal of China Tourism Research, 10(3), 323–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S. L., & Lusch, R. F. (2004). Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing. Journal of Marketing, 68(1), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-Vázquez, M., Castellanos-Verdugo, M., & Oviedo-García, M. A. (2017). Shopping value, tourist satisfaction and positive word of mouth: The mediating role of souvenir shopping satisfaction. Current Issues in Tourism, 20(13), 1413–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vena-Oya, J., Castaneda-García, J. A., Rodríguez-Molina, M. A., & Frías-Jamilena, D. M. (2021). How do monetary and time spend explain cultural tourist satisfaction? Tourism Management Perspectives, 37, 100788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, I. A., Huang, G. I., & Li, Z. C. (2024). Axiology of tourism shopping: A cross-level investigation of value-in-the-experience (VALEX). Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 48(3), 549–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y. H., Yang, F. X., & Leong, M. M. (2024). In-destination online shopping: A new tourist shopping mode and innovation for cross-border tourists. Tourism Recreation Research, 49(6), 1427–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, M. C., Ramasamy, B., Chen, J., & Paliwoda, S. (2013). Customer satisfaction and consumer expenditure in selected European countries. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 30(4), 406–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H., & Littrell, M. A. (2003). Product and process orientations to tourism shopping. Journal of Travel Research, 42(2), 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y. H. E., & Wu, C. K. (2008). Relationships among experiential marketing, experiential value, and customer satisfaction. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 32(3), 387–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yüksel, A. (2007). Tourist shopping habitat: Effects on emotions, shopping value and behaviours. Tourism Management, 28(1), 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V. A. (1988). Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. Journal of Marketing, 52(3), 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H., Zhang, J., & Kuwano, M. (2012). An integrated model of tourists’ time use and expenditure behaviour with self-selection based on a fully nested Archimedean copula function. Tourism Management, 33(6), 1562–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Path | Standardized Estimate | Results |

|---|---|---|

| H1: ENT → SAT | 0.082 ** | Supported (+) |

| H2: EXP → SAT | −0.003 | Not Supported |

| H3: ESC → SAT | 0.028 | Not Supported |

| H4: FVP → SAT | 0.278 *** | Supported (+) |

| H5: FVM → SAT | 0.144 *** | Supported (+) |

| H6: EPV → SAT | 0.209 *** | Supported (+) |

| H7: EQ → SAT | 0.259 *** | Supported (+) |

| H8: ENT → LOY | 0.059 | Not Supported |

| H9: EXP → LOY | 0.034 | Not Supported |

| H10: ESC → LOY | 0.014 | Not Supported |

| H11: FVP → LOY | 0.202 *** | Supported (+) |

| H12: FVM → LOY | 0.194 *** | Supported (+) |

| H13: EPV → LOY | 0.140 ** | Supported (+) |

| H14: SAT → LOY | 0.333 *** | Supported (+) |

| H15: SAT → MON | 0.158 ** | Supported (+) |

| H16: SAT → TIM | 0.132 ** | Supported (+) |

| Model | Path Coefficients | X2 | d.f. | ΔX2 | Δd.f. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unconstrained model | 69.431 | 36 | 1 | |||

| ENT → SAT | High INV | 0.094 ** | 70.381 | 37 | 0.95 | 1 |

| Low INV | 0.058 ** | |||||

| EXP → SAT | High INV | 0.046 | 71.488 | 37 | 2.056 | 1 |

| Low INV | −0.054 | |||||

| ESC → SAT | High INV | 0.013 | 70.377 | 37 | 0.331 | 1 |

| Low INV | 0.092 | |||||

| FVP → SAT | High INV | 0.206 *** | 72.75 | 37 | 3.318 | 1 |

| Low INV | 0.326 *** | |||||

| FVM → SAT | High INV | 0.103 | 70.095 | 37 | 0.663 | 1 |

| Low INV | 0.150 ** | |||||

| EPV → SAT | High INV | 0.196 *** | 69.434 | 37 | 0.003 | 1 |

| Low INV | 0.169 ** | |||||

| EQ → SAT | High INV | 0.339 *** | 69.461 | 37 | 0.029 | 1 |

| Low INV | 0.250 *** | |||||

| ENT → LOY | High INV | 0.036 | 70.323 | 37 | 0.891 | 1 |

| Low INV | 0.091 | |||||

| EXP → LOY | High INV | −0.009 | 70.392 | 37 | 0.961 | 1 |

| Low INV | 0.054 | |||||

| ESC → LOY | High INV | 0.027 | 69.46 | 37 | 0.029 | 1 |

| Low INV | 0.002 | |||||

| FVP → LOY | High INV | 0.145 ** | 71.102 | 37 | 1.671 | 1 |

| Low INV | 0.236 *** | |||||

| FVM → LOY | High INV | 0.178 ** | 70.323 | 37 | 0.853 | 1 |

| Low INV | 0.210 ** | |||||

| EPV → LOY | High INV | 0.168 ** | 69.98 | 37 | 0.549 | 1 |

| Low INV | 0.069 | |||||

| SAT → LOY | High INV | 0.325 *** | 69.461 | 37 | 0.03 | 1 |

| Low INV | 0.294 *** | |||||

| SAT → MON | High INV | 0.159 ** | 74.699 | 37 | 5.268 | 1 |

| Low INV | −0.029 | |||||

| SAT → TIM | High INV | −0.020 | 70.208 | 37 | 0.777 | 1 |

| Low INV | 0.105 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liang, Y.; Huang, S.; Choi, H.C. From Malls to Markets: What Makes Shopping Irresistible for Chinese Tourists? Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 216. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6040216

Liang Y, Huang S, Choi HC. From Malls to Markets: What Makes Shopping Irresistible for Chinese Tourists? Tourism and Hospitality. 2025; 6(4):216. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6040216

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiang, Yutong, Shuyue Huang, and Hwansuk Chris Choi. 2025. "From Malls to Markets: What Makes Shopping Irresistible for Chinese Tourists?" Tourism and Hospitality 6, no. 4: 216. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6040216

APA StyleLiang, Y., Huang, S., & Choi, H. C. (2025). From Malls to Markets: What Makes Shopping Irresistible for Chinese Tourists? Tourism and Hospitality, 6(4), 216. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6040216