1. Introduction

Tourist motivation has been a focus in tourism research for a long time. Researchers seek to understand the many reasons why people travel and the psychological, social and environmental factors that influence those decisions. In practice, this knowledge goes beyond academic theory and directly impacts how destinations are marketed, how products are developed and how sustainable tourism can be promoted. As travel patterns continue to evolve—shaped by the rapid growth of digital platforms, changing social norms and climate change—there is a clear need for a holistic approach that captures all the underlying motivations of tourists. A lot of research has been performed on why people travel, often referencing the well-known push–pull paradigm. “Push” factors are internal drivers—rest, novelty, self actualization—while “pull” factors are external attributes that draw people to a place—cultural or natural attractions. Although these frameworks are still influential, contemporary research suggests that motivations can be dynamic, overlapping and change throughout the trip lifecycle. A visitor may initially want cultural enrichment but also family bonding and digital disconnection, so one trip can meet several psychological and relational needs at the same time. Against this backdrop, understanding how different demographic groups—by age or gender—rank these multiple motivations has become more important. Younger travelers might put adventure or self discovery first, while middle-aged travelers might prioritize shared experiences or stress relief.

In this article, we explicitly pose four research questions. RQ1: What motivational categories emerge from tourists’ own open-ended narratives about vacationing? RQ2: How do these motivations cluster and co-occur when analyzed through network-based methods? RQ3: How do demographic variables such as age and gender shape the prevalence and structure of these motivational constellations? RQ4: How can these findings inform destination management strategies, especially in contexts facing overtourism, destination repositioning, or the emergence of new markets?

This article contributes to the current debate on tourist motivation by using a mixed-methods design that combines qualitative insight with quantitative rigor. We use an inductive three-tier coding process to categorize participants’ open-ended responses to the question, “Why is vacationing important to you?” This approach honors the words and experiences of the travelers themselves, allowing themes to emerge directly from participant narratives rather than from preconceived categories. By systematically organizing these coded responses into subcategories and broader motivational domains, we gain a detailed map of how people conceptualize and prioritize travel. Furthermore, we incorporate a network analysis to illuminate how different motivational elements overlap and cluster. While factor-based models have long illustrated that motivations can be grouped under broad headings (e.g., relaxation, novelty, social bonding), network analysis makes it possible to see how those headings are interlinked within participants’ actual statements. Such visualization and co-occurrence metrics help clarify not only which motivations exist but also how they interact. For example, stress relief may frequently co-occur with family bonding, suggesting that for many travelers, rest and relational quality time are inseparable goals. To enrich our understanding of how demographic factors shape these motivational structures, we assess age- and gender-based variations in the data, using post-stratification weights to correct sampling imbalances. This step helps ensure that findings about prevalence rates and co-occurrence patterns approximate the larger population more accurately. Finally, we evaluate how these motivations align with key travel outcomes, such as satisfaction, recommendation likelihood, and return intention, thereby connecting individual motives to broader tourism behaviors.

By formulating the research in this structured way, the study not only advances theoretical debates about the fluidity of motivations but also positions its findings within the wider challenges of destination management. This includes reconciling paradoxes such as comfort versus sustainability, novelty versus familiarity, and digital detox versus connectivity, all of which carry direct consequences for marketing strategies, product design, and policy-making in international tourism (

Font & McCabe, 2017;

Tufft et al., 2024).

Overall, this study makes three main contributions. First, it underscores the value of an inductive coding procedure that can capture subtle, context-specific motivations. Secondly, it applies network analysis to get beyond discrete categories, to see how motivations cluster together that can either reinforce or counterbalance each other. Thirdly it looks at demographic differences in motivation to contribute to wider debates about whether and how age and gender shape the pursuit of rest, novelty, cultural exploration or interpersonal connection. By recognizing that tourists’ motivations rarely exist in isolation, industry stakeholders can create products that respond to multiple motivations in one trip, so travelers can have relaxation and authentic experiences in one go.

2. Literature Review

Tourist motivation has been a major theme in tourism research for decades with multiple frameworks and empirical studies examining what motivates individuals to travel (

Dann, 1981;

Gnoth, 1997;

J. Chen & Zhou, 2020). Traditional theories focus on personal or psychological needs—relaxation, belonging, growth—and also acknowledge that external environmental and cultural factors have a big impact. This section provides an overview of the key theoretical foundations, emerging issues and methodological advancements in tourist motivation research and how these inform and contrast with the mixed-methods, network-oriented approach used in this study.

2.1. Foundational Theoretical Frameworks

One long-standing paradigm is the push–pull framework which distinguishes internal forces (push) from external, destination-specific features (pull) in explaining why people travel (

Jang & Cai, 2002;

Uysal et al., 2008;

Prayag et al., 2017;

Soldatenko et al., 2023). Push factors include a wide range of internal motivations such as rest, novelty or self-discovery while pull factors revolve around tangible or perceived attributes—scenic landscapes, local culture or safe environment (

Lin et al., 2007;

Antón et al., 2014). This dual perspective provides a structured way to integrate psychological needs with the objective qualities of a destination. However, critics argue that push–pull models can overlook how motivations evolve before, during and even after a trip (

L. Su et al., 2018). An often-cited approach to understanding motivation uses human needs theories which prominently feature Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (

S. Huang & Hsu, 2009;

Hsu et al., 2010). When applying Maslow’s theory, researchers suggest that tourists first focus on basic needs like safety and physiological comfort before working towards self-actualization according to

Šimková and Holzner (

2014) and

Tasci and Ko (

2017). This methodology explains why some traveler groups like families with young children focus on safety and relaxation while different segments seek cultural experiences. Research work by

Khoo-Lattimore et al. (

2018) along with

Wu et al. (

2021) supports this argument. Researchers have raised questions about the universal application of Maslow’s stages because of cultural differences and diverse social norms (

Gnoth & Matteucci, 2014). Social belonging takes precedence over individualistic self-realization in collectivist cultures while individualistic societies place higher value on achievements and new experiences.

2.2. Cultural and Demographic Influences

Culture largely shapes why people travel (

Richards, 2018;

Gek-Siang et al., 2020;

Douglas et al., 2024). For example, tourists from communities that value family often have different reasons for traveling compared to people from more individualistic backgrounds (

Cahyanto et al., 2016). Some focus on family and heritage, while others chase personal freedom and adventure (

Matiza, 2022). Plus, global changes like currency swings, political issues, or visa rules can change what people think are must-see places (

Pomfret & Bramwell, 2014). Researchers stress that studying these motivations can show how they stay the same or change with the times. Besides culture, factors like age and gender are also worth noting (

Alén et al., 2016;

Albayrak & Caber, 2018;

Fieger et al., 2017). Younger travelers often look for adventure, personal growth, and social approval, wanting new experiences and connections (

Rita et al., 2018). In contrast, those in middle age usually prioritize family time or a break from work, focusing on relaxation and bonding (

Jönsson & Devonish, 2008). When comparing genders, some studies find that women care more about emotional well-being and social ties, while men often seek thrills or new experiences (

Gülmez et al., 2025). Other research suggests these differences are not as strong when you consider cultural or situational factors (

Grimm & Needham, 2012). Women are influenced more by cultural experiences and relationships in their travel choices, while men lean toward adventure and relaxation (

Jönsson & Devonish, 2008). Research from many years ago already pointed out that men tend to prefer novelty and adventurous activities more than women do (

Mieczkowski, 1990;

Uysal et al., 1996).

Recent studies also emphasize how demographic distinctions interact with broader international trends. For instance, destinations struggling with overtourism are urged to use demographic segmentation (age, gender, cultural background) to redistribute flows and design alternative experiences (

Oklevik et al., 2019;

; Sibrijns & Vanneste, 2021). At the same time, new destinations emerging on the global tourism map face different challenges: they often try to avoid a homogenized image by highlighting novelty, authenticity, or cultural differentiation (

Capocchi et al., 2019;

Szromek et al., 2019). These strategic concerns show how demographic and cultural findings can be operationalized within destination repositioning and diversification debates.

2.3. Technological and Environmental Developments

Recent changes in digital technology have opened up new questions about what drives people to travel (

Egger et al., 2020;

Servidio & Ruffolo, 2016;

X. Liu et al., 2020;

Sreen et al., 2023). On one hand, social media and online groups help travelers find unique spots and connect with others who have similar interests, boosting their curiosity and creating new attractions that were harder to access before (

Edwards et al., 2017). On the other hand, some people are looking for “digital detox” trips to escape from their always-on lifestyles (

Y. Liu & Hu, 2021). This shows that technology can help us find new experiences but can also be a reason to step back, making things more complicated than older theories suggested about travel motivation (

Li et al., 2020). At the same time, more travelers are considering sustainability and environmental issues as important factors (

M. Carvache-Franco et al., 2022;

Sirakaya-Turk et al., 2024). Trends like ecotourism and community-based travel show a growing interest in places that match their eco-friendly values (

Wang et al., 2014). Some travelers are even factoring in their carbon footprints or wildlife conservation efforts more than those who simply focus on adventure or cost (

Khalilzadeh et al., 2024). But there is still a push–pull situation between making profits and sticking to sustainable practices, which can be a challenge for destinations trying to satisfy both travelers and environmental needs (

M. Carvache-Franco et al., 2022). As a result, the goals tied to sustainability can sometimes clash with other needs, like convenience and saving money, which traditional models do not always fully explain.

From a strategic standpoint, these developments also highlight tensions that DMOs and policymakers must manage. For example, the simultaneous demand for high-quality connectivity and authentic “digital detox” experiences forces destinations to design tiered service offers. Similarly, the desire for both convenience and sustainability illustrates the paradoxical expectations that destinations—particularly those undergoing regeneration after crises—must reconcile. By situating technological and environmental drivers within this strategic context, motivation research can speak directly to current international debates on tourism transformation.

2.4. Health and Wellness Dimensions

Health and wellness considerations have steadily moved from niche markets (e.g., spa or medical tourism) to mainstream motivators (

Coffey & Csikszentmihalyi, 2013;

J. Chen & Zhou, 2020). Many travelers now seek stress reduction, mental restoration, or lifestyle improvements (

Smith, 2023). A qualitative study conducted among domestic tourists in Jordan (N = 232) examined tourism experiences, travel motivations, and travel lifestyle preferences. The findings confirmed that the primary motivating factors behind domestic tourism experiences were those positively affecting tourists’ well-being, namely recreation, relaxation, escape from daily routines, rejuvenation, and enjoyment (

Allan, 2025). Major health events, including the COVID-19 pandemic, have reinforced the importance of safety and well-being, with concerns over hygiene, social distancing, and personal security shaping travel decisions (

Aebli et al., 2021;

Orîndaru et al., 2021). Dest inations that can credibly promise safe yet enriching experiences may gain a competitive advantage (

Dwyer & Kim, 2003).

2.5. Evolving Methodologies

Methodological approaches to tourist motivation have matured alongside these theoretical and topical expansions (

Kozak, 2015). Early reliance on quantitative measures—through factor analysis or structural equation modeling—provided foundational insights into shared motivational dimensions and allowed robust hypothesis testing (

Albayrak & Caber, 2018). Nevertheless, purely quantitative designs risk missing the personalized narratives or situational nuances that shape why individuals travel (

Hsu et al., 2010). In recognition of these complexities, qualitative and mixed-method designs have grown in popularity, incorporating open-ended interviews, focus groups, or textual analysis to reveal subtler dimensions (

Grimm & Needham, 2012). Network analysis and other computational techniques add a new dimension to motivation research (

Khalilzadeh et al., 2024). Instead of viewing motivations as isolated factors or purely hierarchical constructs, network-based methods treat them as nodes that may cluster, overlap, or generate unexpected patterns of co-occurrence. This approach has proven especially useful in identifying how motivations connect across different demographic or cultural subgroups and in illustrating that many travelers hold multiple motivations simultaneously (

Sun et al., 2024).

Many studies show that understanding motivation can help to improve areas like marketing and planning (

Prayag et al., 2017;

Rita et al., 2018;

Vujičić et al., 2020;

Kyriakaki & Kleinaki, 2022). Destinations often tailor their marketing based on factors like age, culture, or specific reasons people travel, such as wanting to relax, go on an adventure, or focus on wellness (

Antón et al., 2014;

Yoo et al., 2018). However, it can be challenging to balance money-making goals with ethical or environmental concerns. For example, a place might market itself as eco-friendly or community-focused (

Lai & Nepal, 2006), but the lure of mass tourism and the money it brings can muddle those ideals (

M. Carvache-Franco et al., 2022). There is also an ongoing discussion about how stable people’s motivations are in such a fast-changing world. Events like crises (

Aebli et al., 2021), new technology (

Egger et al., 2020), and changes in travel rules can really alter what people want. Folks might shift from wanting new experiences to prioritizing health, or from wanting to be social to enjoying some alone time, based on what’s happening around them. Because of this, researchers are pushing for more flexible approaches that can adapt to these changes over time (

Sreen et al., 2023).

Building on these foundations, the current study explicitly addresses the call for contextualized and flexible frameworks. By combining inductive qualitative coding with quantitative network analysis, we not only capture emergent categories but also examine how paradoxical motivations—such as novelty and familiarity, sustainability and comfort—manifest across demographic groups (

Mariani & Baggio, 2020;

Blomstervik & Olsen, 2024). Importantly, this methodological choice also allows us to translate findings into actionable insights for DMOs, overtourism destinations seeking regeneration, and emerging destinations aiming to differentiate their market positions (

Balletto et al., 2025).

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection and Sampling

Data were collected through a web-based survey administered by a marketing firm adhering to the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in October 2024. Of the 3960 potential respondents initially contacted, 604 provided detailed open-ended responses. In Hungary, where the retirement age for men is 65 and health status typically declines significantly thereafter, our study’s travel-related criteria significantly limited participation among older adults. Only 17 individuals over 65 qualified for our sample, as the requirements for frequent or recent vacation experiences excluded many in this demographic. This sampling constraint prevents us from drawing generalizable conclusions about older traveler populations. The situation was further compounded by our recruitment strategy through an online marketing firm, which prioritized participants with substantial international travel experience within the past two years to ensure rich, recent vacation memories—a criterion that inadvertently reduced the representation of older individuals in our final sample. All analyses were executed using R Studio 2024.12.0 Build 467 with R-4.4.2 on Windows.

3.2. Qualitative Coding Procedure

An inductive three-tier coding framework was implemented to analyze responses to the question “Why is vacationing important to you?” In Tier 1, three trained coders grouped raw statements into broad themes, avoiding predefined categories to allow patterns to emerge naturally. In Tier 2, similar ideas were merged into 38 subcategories (e.g., “Stress Relief,” “Family Time,” “Discovering New Places”). Finally, in Tier 3, these subcategories were combined into eight broader categories, such as Physical & Mental Renewal, Social Bonding, and Novelty & Adventure. Intercoder reliability metrics (e.g., Krippendorff’s alpha, Cohen’s kappa) were collected to assess consistency.

The unweighted sample deviated from known population distributions for age and gender. A post-stratification weighting scheme was therefore applied to approximate broader demographic proportions. Because no participants in the 65+ group provided full responses, that category was assigned a weight of zero to avoid distorting the sample. By applying these weights, subsequent analyses (e.g., prevalence estimates, co-occurrences, and network metrics) more reliably mirror a general population profile.

Following the final coding, each participant’s open-ended response was translated into eight binary indicators denoting presence or absence of the main motivational categories (e.g., “Social Bonding,” “Cultural Exploration”). We then examined three outcome variables related to participants’ travel behaviors: Satisfaction Dependency (from 1 = self-driven satisfaction to 5 = externally influenced satisfaction), Recommendation Likelihood (from 1 = never recommend to 5 = always recommend), Return Intention (from 1 = never revisit to 5 = always revisit)

We used linear regressions to assess whether mentioning a particular motivational category predicted higher or lower scores on these outcomes. Secondary analyses explored the relationship between motivations and the number of vacation days taken domestically or abroad, testing whether participants mentioning certain categories (e.g., “Escaping Routine,” “Nature Immersion”) also reported longer or more frequent vacations.

3.3. Data Analysis

After coding and weighting, we conducted a two-pronged analytical strategy that integrated quantitative metrics with qualitative validation:

Weighted prevalence estimates were calculated for each subcategory to detect potential differences by age or gender. For instance, we compared whether younger participants were more prone to mention novelty, or whether women emphasized rest and relaxation more than men. The results were visualized in frequency plots to highlight notable demographic shifts.

To examine how different motivations cluster, we transformed the coded data into an adjacency matrix, where each node represented a motivational subcategory and edges represented participants who mentioned both subcategories in the same response. We then applied modularity-based clustering and measured edge weights to identify strongly linked motivations. Metrics such as network density and clustering coefficients were computed for the dataset overall and for subgroups (e.g., male vs. female, younger vs. older). These computations clarified which motivations frequently co-occur, indicating that travelers view them as intertwined (e.g., “Stress Relief” often appearing with “Family Time”).

To maintain a participant-centered perspective, we retained selected verbatim quotes to demonstrate how coded motivations manifest in real-world statements. For instance, individuals who mentioned “escaping the daily grind” often offered spontaneous remarks about “freedom from chores,” linking these elements in ways consistent with the quantitative co-occurrence data.

All survey procedures complied with GDPR regulations, ensuring participants provided informed consent and that data remained de-identified before analysis. This multifaceted methodology aims to capture the complexity of tourist motivation by honoring the nuance of open-ended responses while employing rigorous quantitative tools to identify patterns and test relationships. In the following sections, we detail the empirical results of these analyses and discuss how demographic factors shape the ways travelers articulate their reasons for vacationing.

4. Results

This section provides an integrated account of tourist motivations identified through a mixed-method design that combines quantitative techniques, including network metrics and co-occurrence frequencies, with qualitative narrative illustrations. Subsequent subsections examine demographic differences, modularity analyses, co-occurrence patterns, network metrics, and selected regression results.

4.1. Sample Coding Table

An illustrative coding table was created to connect raw responses with the refined categories and subcategories (

Table 1).

4.2. Refined Categories and Subcategories

Analysis of the first-tier codes led to the grouping of overlapping themes into 38 subcategories. These subcategories were then merged into eight broader categories, including Physical & Mental Renewal, Escaping Routine, Cultural Exploration, Novelty & Adventure, Social Bonding, Nature Immersion, Comfort & Care, and Barriers & Constraints. Each category draws on recurrent elements identified in participants’ open-ended responses. Physical & Mental Renewal, for example, combines themes of rest, stress relief, and energy recharge, while Social Bonding encompasses family time and partner bonding (

Table 2).

4.3. Overview of Tourist Motivation Categories and Subcategories

Physical & Mental Renewal reflects participants’ needs for rest and tranquility. Social Bonding addresses the aim of spending time with partners, children, and friends. Novelty & Adventure highlights exploration and the desire to discover unfamiliar places. Cultural Exploration focuses on immersion in local customs and heritage. Escaping Routine brings together motivations related to breaking free from everyday constraints. Nature Immersion addresses the importance of landscapes, climate, and water-based activities. Comfort & Care covers relief from chores and housekeeping. Barriers & Constraints captures financial, time-related, and health-related restrictions.

4.4. Prevalence of Motivations

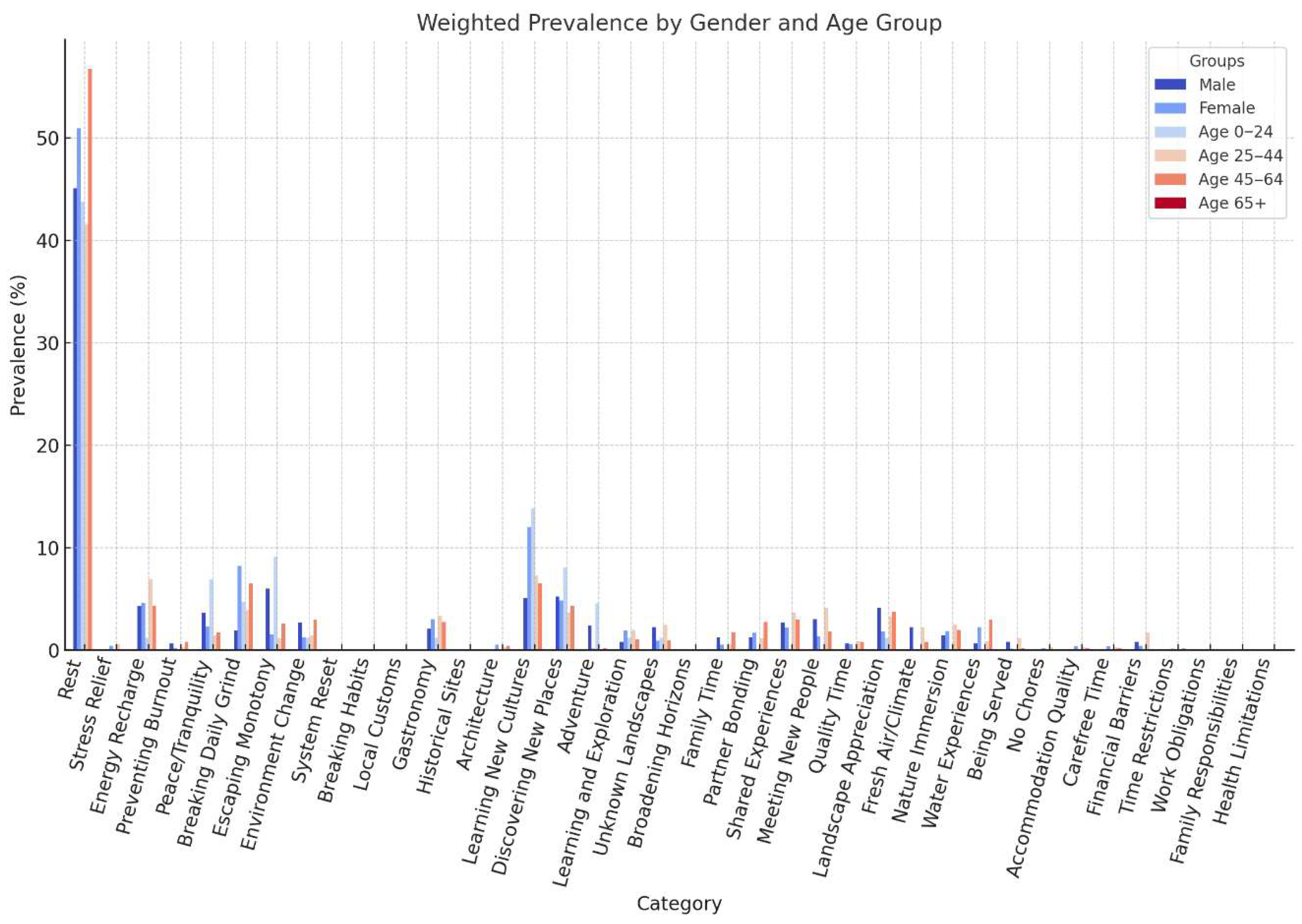

A weighted prevalence analysis identified demographic differences in the frequency with which participants discussed certain subcategories. Gender comparisons revealed that women referred more often to rest-oriented motivations such as stress relief and energy recharge, whereas men were more inclined to mention elements of novelty and exploring new environments. Age-based comparisons showed that younger participants (0–24) were more likely to emphasize adventure and horizon-broadening, while middle-aged participants (25–44 and 45–64) highlighted family time, shared experiences, and energy renewal. These observations appear on

Figure 1, which illustrates subcategory prevalence by age and gender and shows that motivations often shift along life-stage lines.

4.5. Modularity Analysis

Hierarchical clustering yielded three major clusters: Rejuvenation, Social Bonding, and Exploration & Novelty. The Rejuvenation cluster centers on rest-oriented themes, while Social Bonding addresses relational motivations, and Exploration & Novelty emphasizes experiences involving travel and discovery.

Table 3 shows the subcategories that define each of these clusters.

4.6. Edge-Weight Analysis

An edge-weight analysis further examined how frequently particular subcategories were mentioned in tandem. Higher weights indicated stronger co-occurrences. Stress Relief and Energy Recharge co-occurred at a high rate (weight of 0.78), suggesting that participants see them as related motivations. Family Time and Shared Experiences also clustered tightly, as did Adventure and Discovering New Places.

Table 4 details the highest co-occurrence pairs, reinforcing the patterns that emerged from the modularity analysis.

4.7. Narrative Validation

Statements from participants corroborate these quantitative findings. One participant noted that vacations help them “escape daily pressures and rebuild mental energy,” illustrating how relaxation and stress relief connect in an individual’s perspective. Another reflected that “shared experiences with family are what make a trip meaningful,” capturing the Social Bonding dimension. Participants who emphasized Novelty & Adventure frequently described “a broader view of the world” or “expanding personal horizons,” aligning with the strong link between exploration and personal growth.

4.8. Subgroup Comparisons

Gender-based comparisons showed that women tended to give more attention to rejuvenation and care, while men prioritized exploratory and novelty-driven themes. Age-based comparisons confirmed that younger respondents placed higher value on adventure and exploration, while those in the middle-aged groups underlined family time and relaxation. Analyses of domestic and foreign vacation days revealed that participants who cited escaping routine, novelty, or nature reported longer and possibly more frequent vacations than those citing barriers or comfort-focused motivations. This suggests that travelers drawn to novelty or adventure may devote more time and resources to trips, while those emphasizing constraints or care-centered aims may take shorter breaks.

4.9. Co-Occurrence Patterns

Pairwise, triplet, and quadruplet co-occurrences were considered to see how participants grouped themes in their actual statements. Rest-related subcategories such as Relaxation, Recharging, and Rest tended to appear frequently together, and were also linked with broader motivations like exploration. Breaking away from the daily grind was mentioned in conjunction with no cooking or cleaning, reflecting a desire to escape routine tasks at home. The results are shown on

Figure 2.

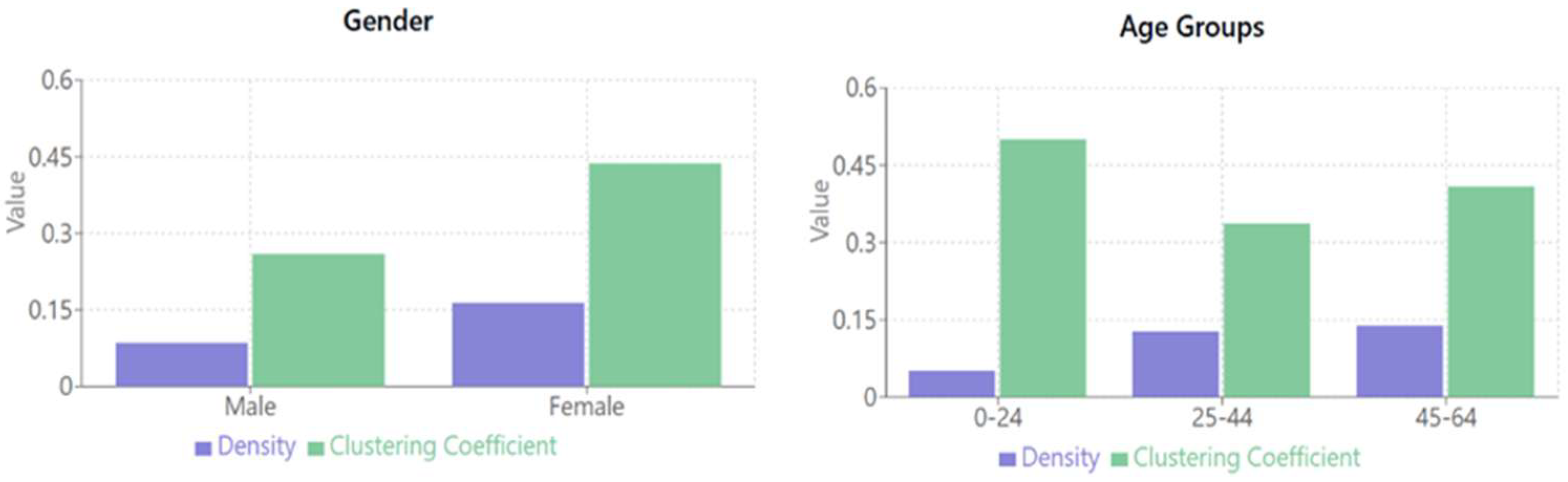

4.10. Network Metrics

Network metrics reveal additional demographic distinctions.

Figure 3 outlines how density and clustering coefficients differ across subgroups. Females showed tighter connections among rest-oriented subcategories, males exhibited a more expansive set of links to novelty-related themes, and older respondents displayed higher overall network density. Younger participants displayed fewer edges, suggesting a narrower set of priorities or less overlap among them. These findings hint that motivations may become more multifaceted with age, especially in the presence of work stress or family responsibilities.

4.11. Additional Regression Results

A series of linear regressions used the eight main categories as predictors for Satisfaction Dependency, Recommendation Likelihood, and Return Intention. The results showed low explanatory power (R-squared values below 0.02) when the categories were considered individually, suggesting that motivations alone do not explain all variability in these outcomes. For instance, Comfort & Care featured positive relationships with satisfaction and repeat visitation, but adding multiple motivation categories to the models did not meaningfully raise R-squared values.

Participants may prioritize rest, novelty, cultural experiences, or bonding activities, and they regularly combine multiple motivations for a single trip. The network analyses clarify the intensities of these connections and suggest that factors such as age and gender shape the intricacy of motivational structures. Co-occurrence data and direct participant narratives reinforce the idea that travel motivations rarely hinge on a single reason. Instead, rest, novelty, cultural interest, and social needs become intertwined.

5. Discussion

This study set out to uncover how tourists articulate and interconnect their motives for travel, and the results indicate that motivations are simultaneously diverse and intertwined. Physical & Mental Renewal, Social Bonding, and Novelty & Adventure emerged as prominent categories across demographic segments. While previous work on tourist motivation (

Al Ansaari, 2019;

Veerasoontorn & Beise-Zee, 2010;

D. N. Su et al., 2020;

Nikjoo & Ketabi, 2015) often treated these drivers as discrete push or pull factors, our findings show that travelers regularly combine them, sometimes within the same statement. This multidimensionality echoes the notion that motivations are rarely static or singular; instead, they morph in response to personal, social, and situational factors.

The discovered patterns reaffirm some classic approaches. Internal drives to rest or escape stress (push factors) and external attributes such as new environments (pull factors) remain highly relevant (

Dann, 1981;

Jang & Cai, 2002). Participants’ emphasis on relaxation, family connection, and novelty resonates with push–pull logic (

L. J. Chen & Chen, 2015;

Wen & Huang, 2019). However, the frequent co-occurrence of different motives suggests that conventional, factor-based motivational models can underestimate the degree of overlap among rest, bonding, and exploration. Further, demographic influences—particularly age and gender—support established distinctions in travelers’ priorities (

Alén et al., 2016). Yet, our data reveal nuances that challenge neat generalizations, such as middle-aged participants citing both rest-oriented themes and novel experiences, or younger travelers seeking social belonging alongside adventure.

One notable outcome concerns the regression models. Although several motivational categories showed positive associations with satisfaction, recommendation likelihood, or return intention, the explanatory power of these models remained low (R2 < 0.02). This finding suggests that motivations, while important, are insufficient as stand-alone predictors of behavioral outcomes. Theoretically, this aligns with network-oriented perspectives that view motivations as interdependent rather than linear drivers. Practically, it implies that DMOs and marketers must consider situational moderators—such as trip quality, group dynamics, or resource constraints—when designing strategies. Segmenting solely by motivation risks overlooking the contextual contingencies that shape whether a trip becomes satisfying or recommendable.

The practical relevance of our findings can be deepened by linking them explicitly to destination management strategies. For destinations struggling with overtourism, the coexistence of contradictory motives—comfort vs. sustainability, novelty vs. familiarity—offers a tool for repositioning. For instance, spreading visitor flows into less congested areas can address novelty-seeking demands while also relieving stress on core attractions. For emerging destinations, demographic distinctions in priorities (e.g., women emphasizing wellness and bonding, younger travelers valuing novelty and adventure) provide guidance on how to differentiate new market identities without defaulting to homogenized “sun, sea, and sand” branding. Additionally, the observed connections between relaxation and bonding suggest that family-oriented packages should integrate rest facilities with opportunities for shared experiences. For DMOs, this translates into product designs that blend paradoxical expectations rather than privileging one.

International trends further contextualize these implications. Post-COVID regeneration strategies must address heightened demand for wellness and safety, while simultaneously appealing to desires for exploration and cultural connection (

Y. T. Huang et al., 2022;

González-Sánchez et al., 2023). Digital detox tourism represents another growing niche: our findings show that the wish to disconnect is tied to distance and novelty rather than explicitly to technology use, which challenges simplistic “unplugged” marketing (

Hassan et al., 2022). Finally, sustainability debates intersect with convenience demands: tourists may seek eco-friendly products but also emphasize being served and cared for. This paradox signals that destinations need to provide tiered experiences, where sustainable options are available without sacrificing comfort, and where messaging avoids greenwashing but acknowledges practical constraints (

Arenas-Escaso et al., 2024;

Anandpara et al., 2024).

One critical insight emerging from the data is the plurality of tensions and paradoxes in tourist motivations. Although the original analysis flagged broad contradictions—comfort vs. sustainability, digital detox vs. connectivity, novelty vs. familiarity—the open-ended responses reveal how deeply entrenched these paradoxes can be. Traditional push–pull paradigms help us categorize motivations broadly, but they struggle to account for the coexistence of opposing desires in a single trip.

5.1. Comfort vs. Sustainability

Many respondents voiced a desire to experience natural environments and a sense of oneness with nature. One participant wrote:

“Primarily serves the purpose of disconnecting, which I find in nature. Given that I’ve been hiking since childhood, physical exercise doubly serves my good, both mentally and physically. […] Silence, calm, and peace are needed to be able to stand my ground in everyday life again and again.”

Yet other travelers highlighted the importance of convenience and chore-free stays. One respondent noted:

“We escape the daily grind. It’s nice to vacation for convenience too, as I don’t have to cook or clean; I get served. It recharges me mentally and spiritually.”

Catering to these divergent demands can lead to greenwashing—where eco-friendly rhetoric is marketed but not fully realized—or to infrastructural developments that undermine local ecosystems. If major tourism players prioritize cost savings and high-volume comfort, critical voices point out that local environments or smaller-scale operators may be sidelined (

W. Carvache-Franco et al., 2020). This raises broader questions: Are travelers complicit in unsustainable practices when they choose convenience over conservation? Or do these contradictory demands reflect structural constraints, such as the lack of affordable, genuinely eco-focused options?

5.2. Digital Detox vs. Connectivity

Many respondents discussed the desire to disconnect from everyday pressures, but did not explicitly frame it in terms of phone usage or “digital detox.” Instead, several mentioned that leaving home or traveling far is the only way they can truly switch off from work. One participant stated:

“When I’m on vacation but not traveling, I simply can’t stop thinking about work, and my mind keeps racing. Traveling, however, completely switches me off, making me forget about everyday life, work, and tasks.”

Another respondent underscored that distance is a practical shield from intrusion, saying:

“The destination is usually outside the EU, so they can’t reach me in any form. That’s the most important thing to truly relax.”

Far from being superficial quirks, these remarks suggest a broader tension between escaping routine responsibilities and remaining reachable in a hyper-connected world. Destinations thus face an uneasy balancing act between providing robust connectivity for travelers who still need online services, and marketing experiences that promise a meaningful break from electronic routines (

Egger et al., 2020). Critically, one might question whether partial “unplug” offerings simply cater to consumer desire for carefully managed disconnection while reinforcing underlying digital dependencies that shape modern travel.

5.3. Novelty vs. Familiarity

Travelers frequently expressed enthusiasm for exploring new places, but some also emphasized that they are perfectly content at home, or even dislike aspects of travel. One participant extolled novelty, saying:

“Vacation is important to me because I gain many new experiences, can get to know new landscapes, new people, that’s why it’s good.”

Yet another expressed the comfort dimension:

“I can relax at home just as well. I don’t like crowds.”

This ambivalence may thus move the conversation away from more holistic discussions on cultural authenticity, the commodification of local heritage or the homogenization of worldwide travel (

Richards, 2018;

Douglas et al., 2024). A more pointed critique here questions whether tourism companies present sanitized forms of “exotic” offerings to quench tourists’ thirst for something new without exposing them to deeper cultural realities and thus diluting the authenticity that travelers say they long for.

Taken together, these paradoxes suggest that destination managers should not expect to resolve contradictions outright but rather to manage them pragmatically. For example, overtourism destinations can introduce rotational programs that alternate between high-comfort and eco-focused products, while emerging destinations can exploit the novelty–familiarity tension by offering both “first-time discovery” packages and repeat-visitor familiarity programs. Such practical recommendations move beyond descriptive findings and demonstrate how motivational constellations can be operationalized into destination-level strategies.

Threaded through these conflicts is a familiar theme about access to resources—material, technological and institutional—that can either alleviate or exacerbate stresses. Whereas larger companies can often skirt genuine sustainability with token “green” offerings, small destinations without the money or the infrastructure may well struggle to meet the needs of travelers seeking both fabulous amenities and sustainable lodgings. Recognizing these realistic constraints is essential for both DMOs and lawmakers. Where resources and knowhow are scarce, plans may outline stepwise solutions: for example, like supporting local businesses to adopt energy-saving technologies or creating buffer “digital-free” zones without completely reconfiguring the connectivity of the entire destination. Although not as structural as topdown transformations, such approaches demonstrate a pragmatic acknowledgment of navigating conflicting traveler necessities in the real world.

5.4. Reconciling Multiple Motives and the Role of Context

While our findings suggest that tourists do pursue multiple aims, the limited explanatory power of motivations as a predictor of satisfaction nevertheless highlights the role of context- and situation-specific determinants. A visitor might set out for relaxation but appraise the trip as a whole on the nature of interrelational moments, impromptu discoveries or the nature of environmental strains. This fluid dynamic makes it harder to assume that motivations directly dictate satisfaction. Rather, motivations may intersect with on-the-ground conditions—weather, travel delays or group dynamics—to produce complex results.

Additionally, limitations (especially financial) can inhibit travelers from actualizing their professed priorities (

Rozynek et al., 2022). Even people passionate about ecological stewardship or wide-ranging explorations will choose cheaper, more available or less “green” options when prices become out of reach. From a critical point of view, those conditions expose inequalities in who can afford to travel ethically or to pay for niche experiences like “boutique ecotourism.” Without more significant structural changes—like policy incentives for sustainable operators or more public funding for local tourism upgrades—some motives are more poster than practical.

6. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that tourist motivations are best conceptualized not as isolated drivers of behavior, but as complex motivational constellations. Tourists situate their holiday intentions as combinations of disparate psychological connections and concern for others. On the same holiday trip, they conjoin relaxation, escape, bonding, and novelty with concern for self, others, and collective society. The analysis extended classical frameworks in tourism that focused on dichotomies including push–pull or need theories to summarize and differentiate the motivations, since it found evidence of relaxation being associated with adventure and bonding, with paradoxes created between technology–detox, sustainability–pampering, and novelty–familiarity. The use of a mixed-method design, specifically the three-stage coding approach, the inclusion of network analysis, and the reiteration of quantitative results, clearly showed that motivations very much need to be captured as constellations. By using only quantitative tools, researchers may aggregate meanings due to a singular focus on well-studied dimensions. By adding open-ended qualitative input, the results reveal the various nuances that may exist with emergent elements that do not align with pre-set themes. Thus, the results, with a focus on contrasting quantitative metrics that reflect an essential part of motivation to exercise six reasons relevant to motivation, have to acknowledge through inductive and participant-centric means that all 48 items play an important part in describing tourist motivations. Motivations are linked to each other and exist in concurrent combinations. For practitioners, the evidence that tourists enter several paradoxical states of mind concurrently may release them from the pressure of delivering a clear single value addition to the tourist but rather help them to develop products, marketing messages, or practical implementation strategies that accommodate relaxation as well as novelty and bonding. They suggest that by combining these elements in the same product or travel experience, tourists may experience greater satisfaction and enjoyment. However, the observed paradoxes of technology use and sustainability clearly indicate that messaging and programmatic delivery have to carefully consider these two motivational constellations.

These insights carry significant implications for destination management. For destinations challenged by overtourism, the coexistence of relaxation, novelty, and bonding motives suggests the need to diversify offerings spatially and temporally, thereby dispersing flows and reducing pressure on iconic sites. For emerging destinations, findings on novelty versus familiarity highlight opportunities to construct differentiated images that avoid homogenized branding while still accommodating visitors who seek comfort. For DMOs more generally, the co-occurrence of sustainability and convenience motives calls for product strategies that do not treat these as mutually exclusive, but rather integrate eco-conscious choices into comfortable and accessible experiences. By explicitly connecting motivational paradoxes to strategic options, this study provides a roadmap for stakeholders navigating complex market demands.

Future research could build on this methodological framework by tracking how motivation networks shift over time or across varied cultural contexts. Longitudinal designs might reveal how factors such as global crises, technological breakthroughs, or evolving social norms alter the configuration of travel motivations. Such future-oriented work would also help clarify how structural shocks—pandemics, climate change, or economic downturns—reshape motivational constellations and test the resilience of destination strategies (

Seabra & Bhatt, 2022;

Tasnim et al., 2023). These avenues of inquiry would not only advance theoretical debates on the fluidity of push–pull dynamics but also guide more adaptive industry responses to the evolving nature of tourist expectations.

7. Limitations and Future Research

Although this study provides a multifaceted perspective on tourist motivations, several limitations shape its interpretation and point to avenues for future research. First, the absence of participants aged 65 and above limits insights into how motivations might evolve or intensify in later life. Seniors often place heightened emphasis on health, heritage, and extended multi-generational travel, so targeted recruitment of this demographic would clarify whether and how motivational structures differ at older ages.

Second, the cross-sectional design and reliance on self-reported, open-ended data restrict the ability to observe motivational shifts as individuals move through different travel phases. Researchers might address this by employing longitudinal or experimental approaches—such as traveler diaries pre-, mid-, and post-trip—to capture how unexpected events, environmental shifts, or interpersonal dynamics reshape initial motives.

Third, while the study sought demographic variety, the specific cultural and geographical context of the sample inevitably narrows its generalizability. Variations in social norms, economic conditions, and collective versus individualist orientations could all alter the ways motivations cluster or co-occur. This underscores the value of cross-cultural or comparative studies that integrate local factors more explicitly. Additionally, participants’ references to sustainability, digital engagement, and comfort often proved highly subjective; in destinations where infrastructure or resource constraints differ substantially, these motivations might take on different forms or priorities.

Moving forward, scholars could expand the network analysis framework to incorporate destination attributes, personality traits, or macro-level factors (e.g., economic downturns, public health emergencies). Such multifactor models would illuminate how external and internal drivers interact to shape travel choices. By investigating these possibilities—especially through more inclusive samples and longitudinal tracking—future work can deepen theoretical understanding and help practitioners design tourism experiences that meet the complex and evolving motivations of diverse traveler segments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.L., Z.B., É.B.B., V.F. and A.M.; methodology, A.L., R.B. and A.M.; formal analysis, A.L., R.B. and A.M.; investigation, A.L., Z.B., É.B.B., V.F., R.B. and A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.L., Z.B., É.B.B., V.F., R.B. and A.M. visualization, A.L., R.B. and A.M.; supervision, A.L., Z.B., É.B.B. and V.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Business and Economics of the University of Debrecen (protocol code GTK-KB 006/2025 and approval date 8 September 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aebli, A., Volgger, M., & Talpin, R. (2021). A two-dimensional approach to travel motivation in the context of the COVID-19 pa demic. Current Issues in Tourism, 25(1), 60–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Ansaari, M. A. D. A. (2019). The impact of push & pull factors and Political stability on destination image, tourist satisfaction and the intention to re-visit: The case of Abu Dhabi in the UAE [Doctoral thesis, United Arab Emirates University]. [Google Scholar]

- Albayrak, T., & Caber, M. (2018). Examining the relationship between tourist motivation and satisfaction by two competing methods. Tourism Management, 69, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alén, E., Losada, N., & Domínguez, T. (2016). The impact of ageing on the tourism industry: An approach to the senior tourist profile. Social Indicators Research, 127(1), 303–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, M. (2025). Tourism experiences, motivations, and travel lifestyles preferences for domestic tourists: A case of Jordan. Geojournal of Tourism and Geosites, 58(1), 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anandpara, G., Kharadi, A., Vidja, P., Chauhan, Y., Mahajan, S., & Patel, J. (2024). A Comprehensive Review on Digital Detox: A Newer Health and Wellness Trend in the Current Era. Cureus, 16(4), e58719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antón, C., Camarero, C., & Laguna-García, M. (2014). Towards a new approach of destination loyalty drivers: Satisfaction, visit intensity and tourist motivations. Current Issues in Tourism, 20(3), 238–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenas-Escaso, J. F., Folgado-Fernández, J. A., & Palos-Sánchez, P. R. (2024). Internet interventions and therapies for addressing the negative impact of digital overuse: A focus on digital free tourism and economic sustainability. BMC Public Health, 24(1), 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balletto, G., Ladu, M., Battino, S., & Attard, M. (2025). A methodological perspective on understanding overtourism in Mediterranean Islands. The case of Sardinia region, Italy. City Territory and Architecture, 12(1), 12–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blomstervik, I. H., & Olsen, S. O. (2024). The relationship between personal values and preference for novelty: Conceptual issues and the novelty–familiarity continuum. Current Issues in Tourism, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahyanto, I., Wiblishauser, M., Pennington-Gray, L., & Schroeder, A. (2016). The dynamics of travel avoidance: The case of Ebola in the U.S. Tourism management perspectives, 20, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capocchi, A., Vallone, C., Pierotti, M., & Amaduzzi, A. (2019). Overtourism: A literature review to assess implications and future perspectives. Sustainability, 11(12), 3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvache-Franco, M., Contreras-Moscol, D., Orden-Mejía, M., Carvache-Franco, W., Vera-Holguin, H., & Carvache-Franco, O. (2022). Motivations and loyalty of the demand for adventure tourism as sustainable travel. Sustainability, 14(14), 8472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvache-Franco, W., Carvache-Franco, M., Carvache-Franco, O., & Hernández-Lara, A. B. (2020). Motivation and segmentation of the demand for coastal and marine destinations. Tourism Management Perspectives, 30, 100661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J., & Zhou, W. (2020). The exploration of travel motivation research: A scientometric analysis based on CiteSpace. COLLNET Journal of Scientometrics and Information Management, 14(2), 257–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L. J., & Chen, W. P. (2015). Push–pull factors in international birders’ travel. Tourism Management, 48(6), 416–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffey, J. K., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2013). Wellness as healthy functioning or wellness as happiness: The importance of eudaimonic thinking. In M. K. Smith, & L. Puczkó (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of health tourism (pp. 24–37). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Dann, G. M. S. (1981). Tourist motivation: An appraisal. Annals of Tourism Research, 8(2), 187–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, A., Hoogendoorn, G., & Richards, G. (2024). Activities as the critical link between motivation and destination choice in cultural tourism. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, 7(1), 249–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, L., & Kim, C. (2003). Destination competitiveness: Determinants and indicators. Current Issues in Tourism, 6(5), 369–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, D., Cheng, M., Wong, I. A., Zhang, J., & Wu, Q. (2017). Ambassadors of knowledge sharing: Co-produced travel information through tourist-local social media exchange. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 29(2), 690–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egger, I., Lei, S. I., & Wassler, P. (2020). Digital free tourism—An exploratory study of tourist motivations. Tourism Management, 79, 104098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fieger, P., Prayag, G., & Bruwer, J. (2017). ‘Pull’ motivation: An activity-based typology of international visitors to New Zealand. Current Issues in Tourism, 22(2), 173–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font, X., & McCabe, S. (2017). Sustainability and marketing in tourism: Its contexts, paradoxes, approaches, challenges and potential. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(7), 869–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gek-Siang, T., Ab. Aziz, K., & Ahmad, Z. (2020). Augmented reality: The game changer of travel and tourism industry in 2025. In S. H. Park, M. A. Gonzalez-Perez, & D. E. Floriani (Eds.), The palgrave handbook of corporate sustainability in the digital era (pp. 169–180). Palgrave Macmillan Cham. [Google Scholar]

- Gnoth, J. (1997). Tourism motivation and expectation formation. Annals of Tourism Research, 24(2), 283–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnoth, J., & Matteucci, X. (2014). Response to Pearce and McCabe’s critiques. International Journal of Culture Tourism and Hospitality Research, 8(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Sánchez, R., Alonso-Muñoz, S., Medina-Salgado, M. S., & Torrejón-Ramos, M. (2023). Driving circular tourism pathways in the post-pandemic period: A research roadmap. Service Business, 17(3), 663–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimm, K. E., & Needham, M. D. (2012). Moving beyond the “I” in motivation: Attributes and perceptions of conservation volunteer tourists. Journal of Travel Research, 51(4), 488–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gülmez, M., Soysal, A. N., Büyükdağ, N., Acar, A., Türten, B., & Koçoğlu, C. M. (2025). Pursuit of entertainment or self-expression? Research on adventure tourism. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 12, 1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, T. H., Salem, A. E., & Saleh, M. I. (2022). Digital-free tourism holiday as a new approach for tourism well-being: Tourists’ attributional approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(10), 5974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C. H., Cai, L. A., & Li, M. (2010). Expectation, motivation, and attitude: A tourist behavioral model. Journal of Travel Research, 49(3), 282–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S., & Hsu, C. H. (2009). Effects of travel motivation, past experience, perceived constraint, and attitude on revisit intention. Journal of Travel Research, 48(1), 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y. T., Tzong-Ru, L., Goh, A. P. I., Kuo, J. H., Lin, W. Y., & Qiu, S. T. (2022). Post-COVID wellness tourism: Providing personalized health check packages through online-to-offline services. Current Issues in Tourism, 25(24), 3905–3912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S., & Cai, L. A. (2002). Travel motivations and destination choice: A study of British outbound market. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 13(3), 111–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jönsson, C., & Devonish, D. (2008). Does nationality, gender, and age affect travel motivation? A case of visitors to the Caribbean Island of Barbados. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 25(3–4), 398–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalilzadeh, J., Kozak, M., & Del Chiappa, G. (2024). Tourism motivation: A complex adaptive system. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 31, 100861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoo-Lattimore, C., delChiappa, G., & Yang, M. J. (2018). A family for the holidays: Delineating the hospitality needs of European parents with young children. Young Consumers, 19(2), 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozak, M. (2015). Bargaining behavior and the shopping experiences of British tourists on vacation. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 33(3), 313–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriakaki, A., & Kleinaki, M. (2022). Planning a sustainable tourism destination focusing on tourists’ expectations, perceptions and experiences. Geo Journal of Tourism and Geosites, 40(1), 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, P. H., & Nepal, S. K. (2006). Local perspectives of ecotourism development in Tawushan Nature Reserve, Taiwan. Tourism Management, 27(6), 1117–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Pearce, P. L., & Oktadiana, H. (2020). Can digital-free tourism build character strengths? Annals of Tourism Research, 85, 103037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-H., Morais, D. B., Kerstetter, D. L., & Hou, J.-S. (2007). Examining the role of cognitive and affective image in predicting choice across natural, developed, and theme-park destinations. Journal of Travel Research, 46(2), 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X., Mehraliyev, F., Liu, C., & Schuckert, M. (2020). The roles of social media in tourists’ choices of travel components. Tourist Studies, 20(1), 27–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., & Hu, H. fen. (2021). Digital-free tourism intention: A technostress perspective. Current Issues in Tourism, 24(23), 3271–3274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, M., & Baggio, R. (2020). The relevance of mixed methods for network analysis in tourism and hospitality research. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 32(4), 1643–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matiza, T. (2022). Country image and recreational tourism travel motivation: The mediating effect of South Africa’s place brand dimensions. Tourism and Hospitality Management, 28(3), 519–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mieczkowski, Z. (1990). World trends in tourism and recreation. Peter Lang Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Nikjoo, A. H., & Ketabi, M. (2015). The role of push and pull factors in the way tourists choose their destination. Anatolia, 26(4), 588–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oklevik, O., Gössling, S., Hall, C. M., Steen Jacobsen, J. K., Grøtte, I. P., & McCabe, S. (2019). Overtourism, optimisation, and destination performance indicators: A case study of activities in Fjord Norway. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(12), 1804–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orîndaru, A., Popescu, M.-F., Alexoaei, A. P., Căescu, Ș.-C., Florescu, M. S., & Orzan, A.-O. (2021). Tourism in a post-COVID-19 era: Sustainable strategies for industry’s recovery. Sustainability, 13(12), 6781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomfret, G., & Bramwell, B. (2014). The characteristics and motivational decisions of outdoor adventure tourists: A review and analysis. Current Issues in Tourism, 19(14), 1447–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G., Hosany, S., Muskat, B., & Del Chiappa, G. (2017). Understanding the relationships between tourists’ emotional experiences, perceived overall image, satisfaction, and intention to recommend. Journal of Travel Research, 56(1), 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, G. (2018). Cultural tourism: A review of recent research and trends. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 36, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rita, P., Brochado, A., & Dimova, L. (2018). Millennials’ travel motivations and desired activities within destinations: A comparative study of the US and the UK. Current Issues in Tourism, 22(16), 2034–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozynek, C., Schwerdtfeger, S., & Lanzendorf, M. (2022). The influence of limited financial resources on daily travel practices. A case study of low-income households with children in the Hanover Region (Germany). Journal of Transport Geography, 100, 103329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seabra, C., & Bhatt, K. (2022). Tourism sustainability and COVID-19 pandemic: Is there a positive side? Sustainability, 14(14), 8723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servidio, R., & Ruffolo, I. (2016). Exploring the relationship between emotions and memorable tourism experiences through narratives. Tourism Management Perspectives, 20, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibrijns, G. R., & Vanneste, D. (2021). Managing overtourism in collaboration: The case of ‘From Capital City to Court City’, a tourism redistribution policy project between Amsterdam and The Hague. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 20, 100569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirakaya-Turk, E., Oshriyeh, O., Iskender, A., Ramkissoon, H., & Mercado, H. U. (2024). The theory of sustainability values and travel behavior. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 36(5), 1597–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M. K. (2023). New trends in wellness tourism: Restoration and regeneration. In A. Morrison, & D. Buhalis (Eds.), Routledge handbook of trends and issues in global tourism supply and demand (pp. 480–496). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Soldatenko, D., Zentveld, E., & Morgan, D. (2023). An examination of tourists’ pre-trip motivational model using push–pull theory: Melbourne as a case study. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 9(3), 572–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreen, N., Tandon, A., Jabeen, F., Srivastava, S., & Dhir, A. (2023). The interplay of personality traits and motivation in leisure travel decision-making during the pandemic. Tourism Management Perspectives, 46, 101095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, D. N., Johnson, L. W., & O’Mahony, B. (2020). Analysis of push and pull factors in food travel motivation. Current Issues in Tourism, 23(5), 572–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L., Swanson, S. R., & Chen, X. (2018). Reputation, subjective well-being, and environmental responsibility: The role of satisfaction and identification. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 26(8), 1344–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X., Wang, Z., Zhou, M., Wang, T., & Li, H. (2024). Segmenting tourists’ motivations via online reviews: An exploration of the service strategies for enhancing tourist satisfaction. Heliyon, 10(1), e23539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szromek, A. R., Hysa, B., & Karasek, A. (2019). The perception of overtourism from the perspective of different generations. Sustainability, 11(24), 7151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šimková, E., & Holzner, J. (2014). Motivation of tourism participants. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 159, 660–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasci, A. D., & Ko, Y. J. (2017). Travel needs revisited. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 23(1), 20–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasnim, Z., Shareef, M. A., Dwivedi, Y. K., Kumar, U., Kumar, V., Malik, F. T., & Raman, R. (2023). Tourism sustainability during COVID-19: Developing value chain resilience. Operations Management Research, 16, 391–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufft, C., Constantin, M., Pacca, M., Mann, R., Gladstone, I., & de Vries, J. (2024). The state of tourism and hospitality 2024. McKinsey & Company. Available online: https://www.assoporti.it/media/14649/mckinsey-the-state-of-tourism-and-hospitality-2024-final.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- Uysal, M., Li, X., & Sirakaya-Turk, E. (2008). Push–pull dynamics in travel decisions. In H. Oh (Ed.), Handbook of hospitality marketing management (pp. 412–439). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Uysal, M., McGehee, N. G., & Loker-Murphy, L. (1996). The Australian international pleasure travel market motivation from a gendered perspective. Journal of Tourism Studies, 7(1), 45–57. [Google Scholar]

- Veerasoontorn, R., & Beise-Zee, R. (2010). International hospital outshopping: A staged model of push and pull factors. International Journal of Pharmaceutical and Healthcare Marketing, 4(3), 247–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vujičić, M. D., Kennell, J., Morrison, A., Filimonau, V., Štajner Papuga, I., Stankov, U., & Vasiljević, D. A. (2020). Fuzzy modelling of tourist motivation: An age-related model for sustainable, multi-attraction, urban destinations. Sustainability, 12(20), 8698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.-e., Zhong, L., Zhang, Y., & Zhou, B. (2014). Ecotourism environmental protection measures and their effects on protected areas in China. Sustainability, 6(10), 6781–6798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J., & Huang, S. (2019). The effects of push and pull travel motivations, personal values, and destination familiarity on tourist loyalty: A study of Chinese cigar tourists to Cuba. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 24(8), 805–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W., Kirillova, K., & Lehto, X. (2021). Learning in family travel: What, how, and from whom? Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 38(1), 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, C. K., Yoon, D., & Park, E. (2018). Tourist motivation: An integral approach to destination choices. Tourism Review, 73(2), 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).