Beyond Tourism: Community Empowerment and Resilience in Rural Indonesia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Concept of Community-Based Tourism

2.2. Socio-Economic Resilience

- Economic diversification: The extent to which a community has multiple sources of income beyond tourism.

- Social capital: Trust, cooperation, and networks within the community.

- Institutional capacity: Leadership, governance, and the ability to mobilize resources.

- Adaptive capacity: The ability to respond to change or disturbance effectively.

- Equity and inclusion: Fair distribution of tourism benefits across gender, age, and social groups.

- Ecological sustainability: The integration of environmental stewardship into community practices, ensuring the long-term health of the natural resources upon which tourism depends (Cochrane, 2010; Ruiz-Ballesteros, 2011).

2.3. Relationship Between Community-Based Tourism (CBT) and Community Resilience

2.4. Previous Studies on CBT in Indonesia and Globally

3. Methodology

- Nglanggeran Tourism Village (Yogyakarta)

- 2.

- Penglipuran Tourism Village (Bali)

- 3.

- Jasri Tourism Village (Bali)

- In-depth Interviews: Semi-structured interviews were conducted with key stakeholders, including community leaders, tourism entrepreneurs, representatives of local tourism organizations, and government officials.

- Focus Group Discussions (FGDs): FGDs were held with local residents in each village to understand broader community perceptions regarding the impacts of tourism on livelihoods, social cohesion, and resilience.

- Participant Observation and Field Notes: The researcher engaged in short-term immersion in each site to observe tourism-related activities, village governance meetings, and daily interactions.

- Document Analysis: Secondary data such as village profiles, tourism master plans, and government policies were reviewed to supplement primary sources.

4. Findings

4.1. Community-Based Tourism Models in Each Village

4.1.1. Governance and Participation Structure

4.1.2. Role of Traditional and Cultural Institutions

4.1.3. Local Ownership and Benefit-Sharing Mechanisms

4.2. Dimensions of Socio-Economic Resilience

4.3. Comparative Analysis: Yogya vs. Bali Villages

- Governance Structure

- 2.

- Stage of Tourism Development:

- 3.

- Cultural Integration:

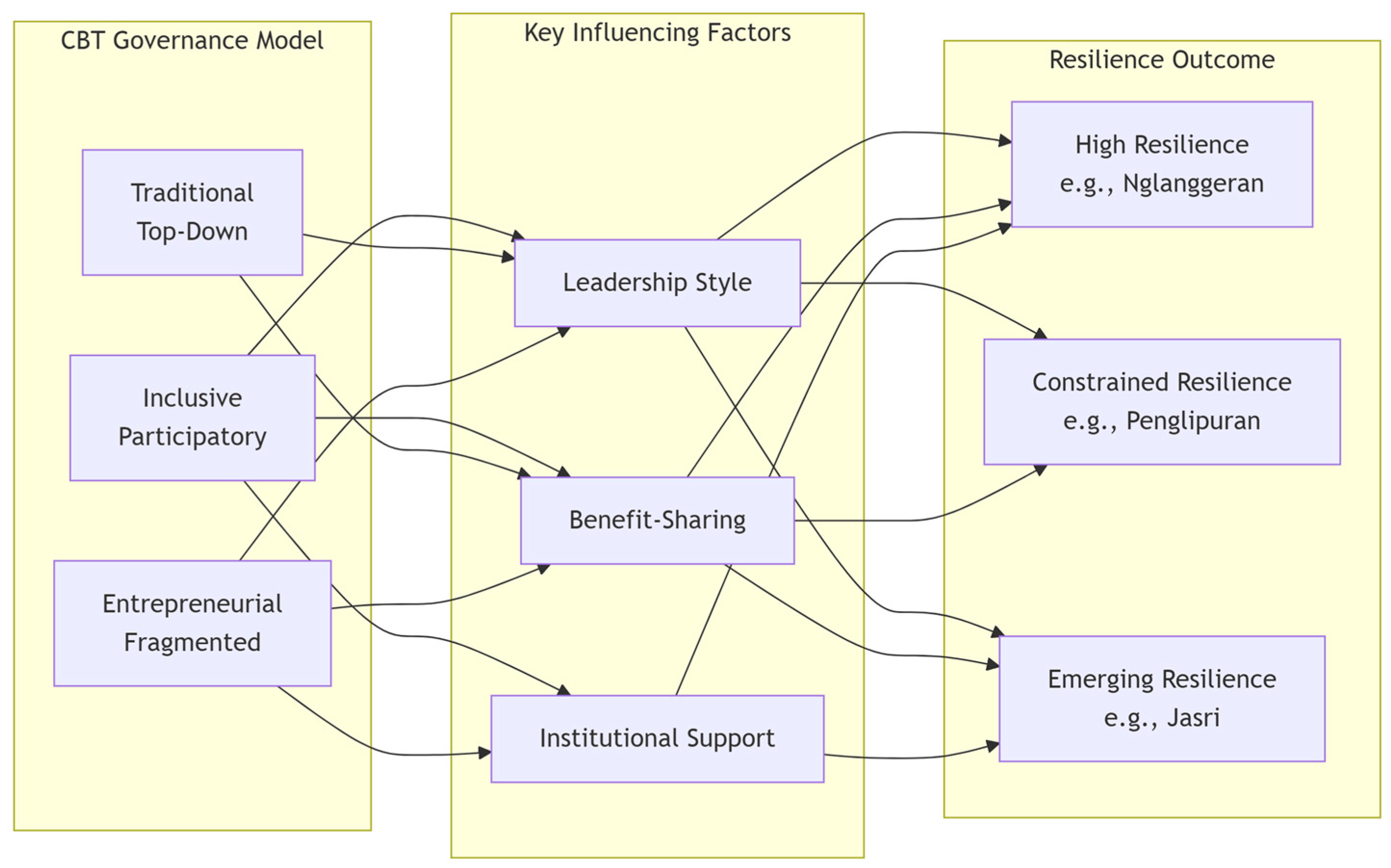

- In Nglanggeran, leadership is distributed and collective, involving youth leaders, women’s groups, and senior community members. External partnerships—with universities, government, and NGOs—have bolstered institutional support, enabling innovation and adaptive learning (Interview with Pokdarwis, July 2024). This aligns with the argument by Beeton (2006) that visionary, collaborative leadership is key to sustainable CBT.

- Penglipuran benefits from strong traditional leadership, which ensures cultural continuity and orderly development. However, its top-down nature can hinder responsiveness to market changes or grassroots innovation, particularly among youth and women (Observation, July 2024). Leadership here is protective rather than transformative.

- Jasri’s leadership is entrepreneurial but fragmented. While local tourism pioneers have initiated creative enterprises, there is little coordination with broader village governance or long-term strategic planning. The lack of institutional anchoring limits scalability and resilience, echoing Giampiccoli and Saayman’s (2018) caution against CBT efforts driven by individual interests without collective mechanisms.

4.3.1. Lessons Learned and Critical Challenges

- Inclusive governance and shared ownership are crucial for community buy-in and long-term sustainability. Nglanggeran’s participatory model has fostered trust and shared responsibility.

- Institutional partnerships can provide access to capacity-building, markets, and innovation. External support was essential to Nglanggeran’s and, to a lesser extent, Penglipuran’s success.

- Cultural legitimacy enhances destination appeal while anchoring tourism within community values. Penglipuran’s strict adherence to Balinese adat structures has preserved authenticity and attracted consistent tourist interest.

4.3.2. Critical Challenges

- Benefit inequality: In Jasri, uneven access to tourism opportunities has led to social tensions and low collective morale. In Penglipuran, non-krama members feel excluded from decision-making and revenue.

- Adaptability: Traditional governance structures like those in Penglipuran may resist rapid adaptation, particularly in response to global shocks like pandemics or climate change.

- Youth engagement: Across sites, youth involvement is uneven. While Nglanggeran has integrated youth into leadership and innovation, Penglipuran and Jasri struggle with generational transitions and digital literacy.

5. Discussion

5.1. How CBT Contributes to or Limits Socio-Economic Resilience

5.2. The Role of Community Agency, Culture, and Local Institutions

5.3. Interaction Between External Actors (Government, NGOs, Private Sector) and Local Communities

5.4. Reflection on the Resilience Framework Used

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

7. Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ardika, I. W. (2003). Bali: Balinese culture and tourism. Udayana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Aryaningtyas, A. T., Maria Th, A. D., & Risyanti, Y. D. (2024). Community engagement and resilience in Indonesian tourism: Lessons from the COVID-19 crisis. Jurnal Ilmu Sosial dan Humaniora, 13(1), 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asker, S., Boronyak, L., Carrard, N., & Paddon, M. (2010). Effective community-based tourism: A best practice manual. Sustainable Tourism Cooperative Research Centre. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beeton, S. (2006). Community development through tourism. Landlinks Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggs, R., Schlüter, M., & Schoon, M. L. (Eds.). (2015). Principles for building resilience: Sustaining ecosystem services in social-ecological systems. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackstock, K. (2005). A critical look at community based tourism. Community Development Journal, 40(1), 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheer, J. M., & Lew, A. A. (Eds.). (2018). Tourism, resilience, and sustainability: Adapting to social, political, and economic change. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Cheer, J. M., & Lew, A. A. (Eds.). (2021). Tourism, resilience, and sustainability: Adapting to social-ecological change. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane, J. (2010). The sphere of tourism resilience. Tourism Recreation Research, 35(2), 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, S. (2006). Cultural tourism, community participation, and empowerment. In M. Smith, & M. Robinson (Eds.), Cultural tourism in a changing world: Politics, participation and (re)presentation (pp. 89–103). Channel View Publications. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/236144502_Cultural_tourism_community_participation_and_empowerment (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2018). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (4th ed.). Sage Publications. Available online: https://pubhtml5.com/enuk/cykh/Creswell_and_Poth%2C_2018%2C_Qualitative_Inquiry_4th/ (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Dangi, T. B., & Jamal, T. (2016). An integrated approach to “sustainable community-based tourism”. Sustainability, 8(5), 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, R., Ali, A., & Galaski, K. (2023). Community-based tourism: Success stories and lessons learned. CABI. [Google Scholar]

- Dodds, R., & Butler, R. (2021). The phenomena of overtourism: A review. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 7(2), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filantropi, B., & Bella, P. A. (2022). Studi keberhasilan pengelolaan desa wisata berbasis community based tourism (studi kasus: Desa nglanggeran, kecamatan patuk, kabupaten gunungkidul, yogyakarta). Jurnal Sains Teknologi Urban Perancangan Arsitektur (Stupa), 4(1), 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, R. (2021). Connection amid fragmentation: The political ecology of community-based tourism. University of Arizona Press. [Google Scholar]

- Folke, C. (2006). Resilience: The emergence of a perspective for social–ecological systems analyses. Global Environmental Change, 16(3), 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujihasa, I. G. M., Widawati, I. A. P. W., & Mahadewi, N. M. E. (2023). Pembangunan Pariwisata di Desa Wisata Penglipuran Melalui Peran Partisipasi Masyarakat, Kewirausahaan Sosial Berkelanjutan dan Inovasi. Ekuitas: Jurnal Pendidikan Ekonomi, 10(2), 290–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giampiccoli, A., & Mtapuri, O. (2012). Community-based tourism: An exploration of the concept(s) from a political perspective. Tourism Review International, 16(1), 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giampiccoli, A., & Saayman, M. (2018). Community-based tourism development model and community participation. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 7(4), 1–27. Available online: https://www.ajhtl.com/uploads/7/1/6/3/7163688/article_16_vol_7_4__2018.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Goodwin, H., & Santilli, R. (2009). Community-based tourism: A success? ICRT Occasional paper 11. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/265278848_Community-Based_Tourism_a_success_Community-Based_Tourism_a_success (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Gössling, S., Scott, D., & Hall, C. M. (2020). Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(1), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C. M., Prayag, G., & Amore, A. (2018). Tourism and resilience: Individual, organisational and destination perspectives. Channel View Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F., Carnicelli, S., Krolikowski, C., Wijesinghe, G., & Boluk, K. (2019). Degrowing tourism: Rethinking tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(12), 1926–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannides, D., & Gyimóthy, S. (2020). The COVID-19 crisis as an opportunity for escaping the unsustainable global tourism path. Tourism Geographies, 22(3), 624–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayat, K. (2023). Power, participation, and perception in community-based tourism. Tourism Management Perspectives, 46, 101089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasso, A., & Dahles, H. (2023). Resilience of community-based tourism initiatives in the Global South post-COVID-19. Annals of Tourism Research Empirical Insights, 4(1), 100088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemy, D. M., Pramono, R., & Juliana. (2022). Acceleration of environmental sustainability in tourism village. International Journal of Sustainable Development and Planning, 17(4), 1273–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lew, A. A. (2014). Resilience in tourism community development. Annals of Tourism Research, 44, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Sanz, J. M., Penelas-Leguía, A., Gutiérrez-Rodríguez, P., & Cuesta-Valiño, P. (2021). Sustainable development and rural tourism in depopulated areas. Land, 10(9), 985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manyara, G., & Jones, E. (2007). Community-based tourism enterprises development in Kenya: An exploration of their potential as avenues of poverty reduction. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 15(6), 628–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Tourism and Creative Economy. (2023). Statistik desa wisata 2023 [Report]. Ministry of Tourism and Creative Economy. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, P. E. (1985). Tourism: A community approach. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, F. H., Stevens, S. P., Pfefferbaum, B., Wyche, K. F., & Pfefferbaum, R. L. (2008). Community resilience as a metaphor, theory, set of capacities, and strategy for disaster readiness. American Journal of Community Psychology, 41(1–2), 127–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novelli, M., Burgess, L. G., Jones, A., & Ritchie, B. W. (2018). ‘No Ebola… still doomed’—The Ebola-induced tourism crisis. Annals of Tourism Research, 70, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okazaki, E. (2008). A community-based tourism model: Its conception and use. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 16(5), 511–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative research & evaluation methods (4th ed.). Sage Publications. Available online: https://aulasvirtuales.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/qualitative-research-evaluation-methods-by-michael-patton.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Pitana, I. G., & Diarta, I. K. S. (2009). Pengantar ilmu pariwisata. Andi. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Ballesteros, E. (2011). Social-ecological resilience and community-based tourism: An approach from Agua Blanca, Ecuador. Tourism Management, 32(3), 655–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheyvens, R. (1999). Ecotourism and the empowerment of local communities. Tourism Management, 20(2), 245–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheyvens, R. (2007). Exploring the tourism–poverty nexus. Tourism Management, 28(1), 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheyvens, R. (2011). The challenge of sustainable tourism development in the Maldives: Understanding the social and political dimensions of sustainability. Asia Pacific Viewpoint, 52(2), 148–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheyvens, R., & van der Watt, H. (2021). Tourism, empowerment and sustainable development: A new framework for analysis. Sustainability, 13(22), 12606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. (2021). Impact of the coronavirus pandemic on the tourism sector in Indonesia [Online Database]. Statista. [Google Scholar]

- Suansri, P. (2003). Community-based tourism handbook. Responsible Ecological Social Tours (REST). Available online: https://www.humanrights-in-tourism.net/sites/default/files/media/file/2020/rc071community-based-tourism-handbook-1269.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Sunaryo, B. (2013). Kebijakan pembangunan destinasi pariwisata: Konsep dan aplikasinya di Indonesia. Gadjah Mada University Press. Available online: https://books.google.co.id/books/about/Kebijakan_pembangunan_destinasi_pariwisa.html?hl=id&id=ikfbnQEACAAJ&redir_esc=y (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Šegota, T., Mihalič, T., & Perdue, R. R. (2022). Resident perceptions and responses to tourism: Individual vs community level impacts. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 32(2), 340–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun, C. (2000). Limits to community participation in the tourism development process in developing countries. Tourism Management, 21(6), 613–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trupp, A., & Sunanta, S. (2017). Gendered practices in urban ethnic tourism in Thailand. Annals of Tourism Research, 64, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. (2021). Best tourism villages 2021. United Nations World Tourism Organization. Available online: https://www.unwto.org (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Wilson, G. A. (2012). Community resilience and environmental transitions. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, E. C. L., & Wong, K. M. (2023). A political ecology of community-based tourism: Power, knowledge, and resilience. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 31(3), 811–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R. K. (2018). Case study research and applications: Design and methods (6th ed.). Sage Publications. Available online: https://uk.sagepub.com/en-gb/eur/case-study-research-and-applications/book250150 (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Zapata, M. J., Hall, C. M., Lindo, P., & Vanderschaeghe, M. (2011). Can community-based tourism contribute to development and poverty alleviation? Lessons from Nicaragua. Current Issues in Tourism, 14(8), 725–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Research (Year) | Context | Methodology | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Manyara and Jones (2007) | Kenya | Case Study | CBT can reduce poverty but requires strong community institutions and external support. |

| Cole (2006) | Bali, Indonesia | Ethnographic Study | Traditional institutions (desa adat) are crucial for cultural tourism but can limit participatory governance. |

| Scheyvens (2007) | Multiple | Conceptual/Theoretical | CBT can empower communities, but elite capture can exacerbate inequalities if not carefully managed. |

| Lew (2014) | Multiple | Literature Review | Resilience in tourism is linked to adaptive capacity, which can be fostered through community-based approaches. |

| UNWTO (2021) | Nglanggeran, Indonesia | Case Study | Strong local leadership and partnerships are key success factors for award-winning tourism villages. |

| Aryaningtyas et al. (2024) | Indonesia | Qualitative Study | Community engagement was a critical factor for resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pramono, R.; Juliana, J. Beyond Tourism: Community Empowerment and Resilience in Rural Indonesia. Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 210. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6040210

Pramono R, Juliana J. Beyond Tourism: Community Empowerment and Resilience in Rural Indonesia. Tourism and Hospitality. 2025; 6(4):210. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6040210

Chicago/Turabian StylePramono, Rudy, and Juliana Juliana. 2025. "Beyond Tourism: Community Empowerment and Resilience in Rural Indonesia" Tourism and Hospitality 6, no. 4: 210. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6040210

APA StylePramono, R., & Juliana, J. (2025). Beyond Tourism: Community Empowerment and Resilience in Rural Indonesia. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(4), 210. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6040210