Techno-Economic Evaluation of Sustainability Innovations in a Tourism SME: A Process-Tracing Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Sustainability Innovations in Tourism

2.1.1. Core Categories of Sustainability Innovations in Tourism

2.1.2. Influencing Factors for Sustainability Innovation in Tourism

2.2. Techno-Economic Evaluation in SMEs

2.2.1. Ex-Post Cost–Benefit Approaches in SMEs

2.2.2. Qualitative Data as a Substitute for Traditional Indicators

2.2.3. Concluding Insights on Balancing Tangible and Intangible Outcomes

2.3. Theoretical Perspectives on Adoption and Learning in Sustainability Innovation

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Strategy

3.2. Case Selection

3.3. Data Collection

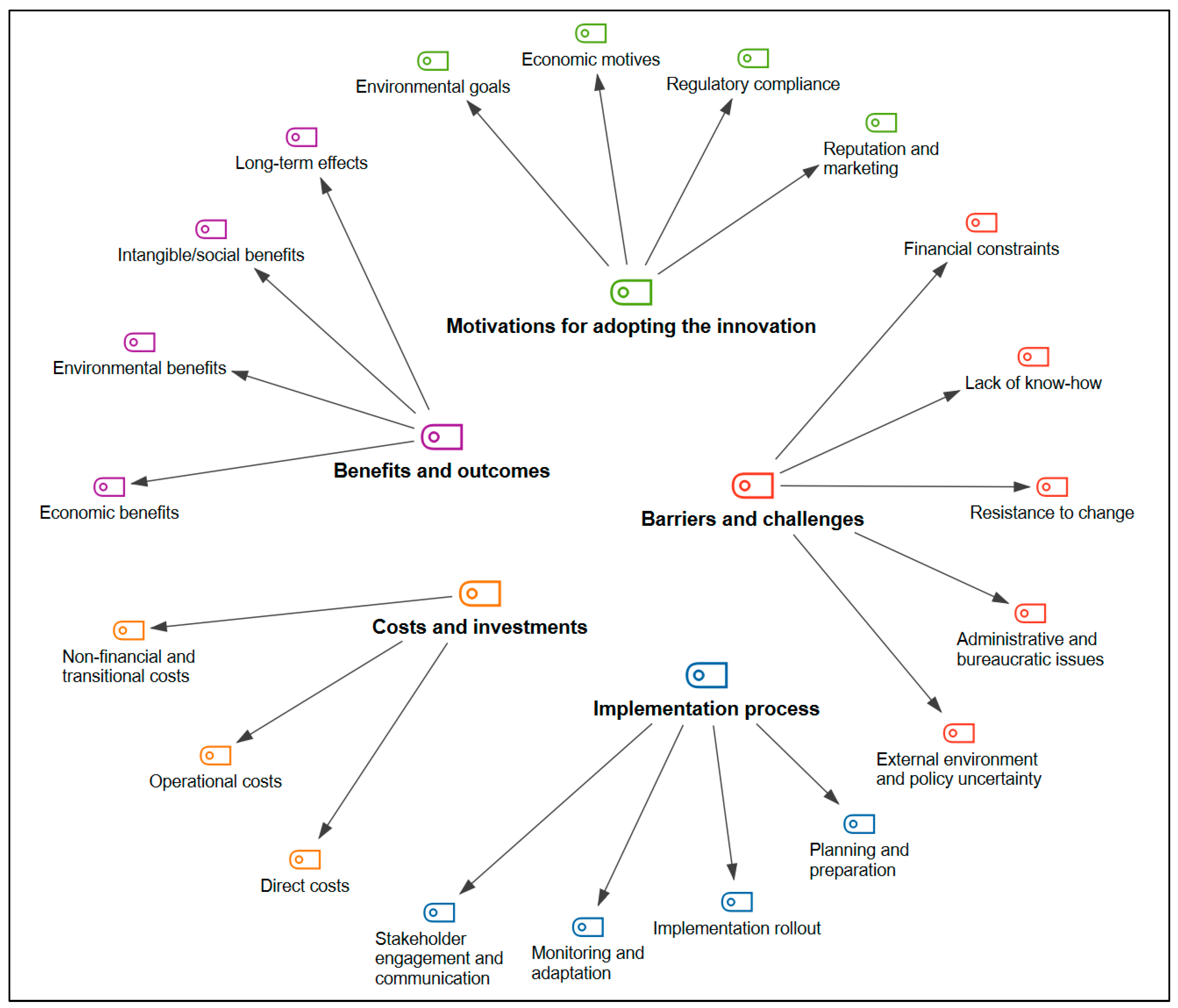

3.4. Data Analysis

3.4.1. Process Tracing

3.4.2. Thematic Analysis and Coding

3.4.3. Techno-Economic Evaluation

4. Results

4.1. Timeline of Innovations

4.1.1. Installation of Solar Collectors (2018)

4.1.2. Launch of Composting Program (2019)

4.1.3. Adjustments and Preparation (2020–2021)

4.1.4. Zero Waste Partnerships (2022–2024)

4.2. Causal Links

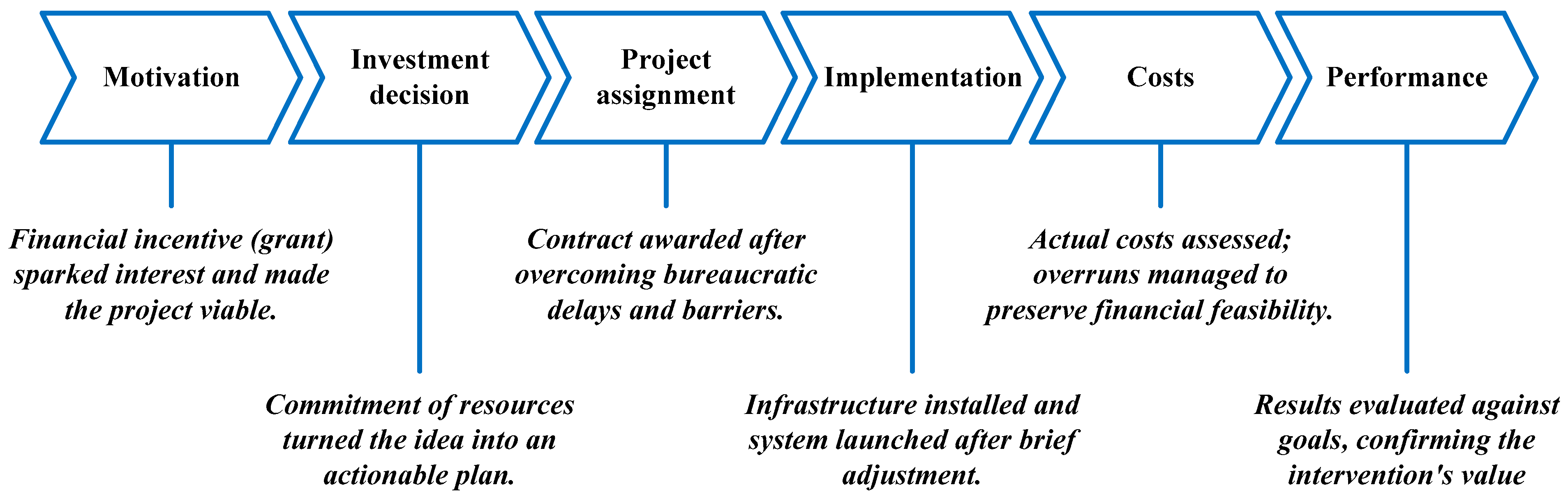

4.2.1. Causal Mechanism

- Motivation (external intervention): A government grant acted as a catalyst for initiating the investment. This reflects a diffusion factor: an external incentive that lowered perceived risk and increased the relative advantage of adoption. Triangulated evidence from interviews with owners, grant documentation, and financial plans confirmed that without this incentive, the hotel likely would not have proceeded due to the associated financial risks. Later, ISO 14001 certification served a similar role, reinforcing adoption by increasing observability and legitimacy in the market.

- Investment decision: Building on this motivation, the hotel made the decision to move forward. Here, the compatibility of solar technology with the hotel’s operations supported adoption, while leadership commitment demonstrates organizational learning through decision-making and capability building. Accounts of the management team’s discussions highlight specific behaviors, such as the owners comparing supplier offers, debating payback times, and framing the investment as a shared long-term goal rather than a short-term expense. Interview accounts of these discussions were consistent with the signed contract records, strengthening confidence that the decision was causally linked to the grant.

- Project assignment and implementation barriers: The next step involved assigning the project to a contractor. During this phase, implementation barriers began to emerge. Bureaucratic requirements caused delays and necessitated adjustments to the original plan, requiring additional managerial effort. Cross-checking manager interviews with correspondence and dated project files confirmed how these delays developed. The manager’s active role was evident: he personally handled licensing paperwork, re-sequenced procurement tasks, and reorganized staff schedules to keep other hotel operations unaffected. These challenges were addressed through organizational learning, as the manager adapted routines and reallocated resources to resolve bottlenecks.

- Implementation and launch: Following the contracting phase, the project transitioned to implementation and was ultimately launched. This stage involved installing the necessary infrastructure and performing initial tests before full-scale operation. Diffusion dynamics are visible here in the trialability of the system and the gradual adjustment period before full adoption. Training sessions show how leadership turned trial operation into a learning process, using mistakes in compost separation or energy monitoring as teaching moments rather than failures. Evidence from observation notes on staff training sessions was compared with technical reports, showing how trial operation gradually became routinized.

- Implementation and operational costs: At this stage, actual costs started to become apparent, differing from the initial budget due to additional expenses and delays. The hotel had to cover its own share beyond the grant, and some cost overruns exerted extra pressure on the project. It was essential to manage spending effectively to maintain the financial viability of the investment. Cost control combined both lenses: diffusion theory explains concerns about economic advantage, while organizational learning highlights the role of financial monitoring routines and staff coordination. Leadership behavior was visible here in the owners’ insistence on weekly budget reviews, renegotiation of supplier terms, and the decision to cut lower-priority expenses to avoid jeopardizing the project. Supplier invoices and budget spreadsheets were checked against interview claims to verify that cost-control actions were indeed implemented.

- Project performance (results): Ultimately, the project produced measurable outcomes, as discussed in Section 4.3. Its performance was evaluated in relation to the original goals and the actual costs incurred. The diffusion lens clarifies why adoption delivered benefits by enhancing relative advantage and observability, while the learning lens explains how routines and feedback sustained these results. Triangulation of utility bills, guest reviews, and staff notes confirmed that performance gains were not only perceived but also measurable. Temporal sequencing further supported attribution. The increase in repeat guests and satisfaction ratings emerged only after visible sustainability practices were in place, while internal documents and field notes showed no other major changes in service model during this period. Context also shaped outcomes. The temporary suspension of composting during COVID created a setback, but it later allowed the hotel to redesign routines with clearer responsibilities and monitoring, resulting in improved performance once the system was restarted. The achievement of the expected results confirmed the value of the intervention, while any deviations were partly attributed to challenges and cost increases experienced during implementation.

4.2.2. Critical Junctures and Alternative Pathways

4.3. Techno-Economic Evaluation

4.3.1. Implementation and Investment Cost

4.3.2. Operating Cost Reduction

4.3.3. Environmental Performance

4.3.4. Operational Improvement

4.3.5. Guest Experience and Perceptions

4.3.6. Overall Cost–Benefit Assessment

5. Conclusions

5.1. Discussion of Key Findings

5.2. Managerial and Societal Implications

5.3. Limitations

5.4. Suggestions for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Questionnaire for Owners and General Manager |

|

| Questionnaire for staff |

|

| Questionnaire for local suppliers |

|

References

- Ali, S., Peters, L. D., Khan, I. U., Ali, W., & Saif, N. (2020). Organizational learning and hotel performance: The role of capabilities’ hierarchy. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 85, 102349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsahafi, R., Alzahrani, A., & Mehmood, R. (2023). Smarter sustainable tourism: Data-driven multi-perspective parameter discovery for autonomous design and operations. Sustainability, 15(5), 4166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andyani, N., Triyuni, N. N., & Puspita, N. (2023). Green purchasing implementation in procurement process of kitchen’s goods in improving environmental awareness at Le Meridien Bali Jimbaran. International Journal of Current Science Research and Review, 6(7), 4859–4871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, C. S., & Moreira, A. C. (2020). Sustainable innovation: Challenges in the tourism industry. In Building an entrepreneurial and sustainable society (pp. 219–245). IGI Global. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyris, C., & Schön, D. A. (1978). Organizational learning: A theory of action perspective. Addison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Avilés-Sacoto, S. V., Harrison, J., & Valencia-Vallejo, J. L. (2023). Technology innovation in tourism supply chains: Opportunities and barriers to adoption in the post-COVID world. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality and Tourism. in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axhami, M., Ndou, V., Milo, V., & Scorrano, P. (2023). Creating value via the circular economy: Practices in the tourism sector. Administrative Sciences, 13(7), 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiocco, S., Leoni, L., & Paniccia, P. M. A. (2023). Entrepreneurship for sustainable development: Co-evolutionary evidence from the tourism sector. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 30(7), 1521–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beach, D., & Rohlfing, I. (2018). Integrating cross-case analyses and process tracing in set-theoretic research: Strategies and parameters of debate. Sociological Methods & Research, 47(1), 3–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, M. N., & Thapa, B. (2013). Motives, facilitators and constraints of environmental management in the Caribbean accommodations sector. Journal of Cleaner Production, 52, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, E., Rey-Maquieira, J., & Lozano, J. (2009). Economic incentives for tourism firms to undertake voluntary environmental management. Tourism Management, 30(1), 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blatter, J., & Haverland, M. (2014). Case studies and (causal-) process tracing. In I. Engeli, & C. R. Allison (Eds.), Comparative policy studies: Conceptual and methodological challenges (pp. 59–83). Palgrave Macmillan UK. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boardman, A. E., Mallery, W. L., & Vining, A. R. (1994). Learning from ex ante/ex post cost-benefit comparisons: The coquihalla highway example. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences, 28(2), 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodhanwala, S., & Bodhanwala, R. (2021). Exploring relationship between sustainability and firm performance in travel and tourism industry: A global evidence. Social Responsibility Journal, 18(7), 1251–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohdanowicz, P., Churie-Kallhauge, A., Martinac, I., & Rezachek, D. (2001, April 5–7). Energy-efficiency and conservation in hotels—Towards sustainable tourism (Volume 21). 4th International Symposium on Asia Pacific Architecture, Honolulu, HI, USA. Available online: http://www.greenthehotels.com/eng/BohdanowiczChurieKallhaugeMartinacHawaii2001.pdf (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Booyens, I., Motala, S., & Ngandu, S. (2020). Tourism innovation and sustainability: Implications for skills development in South Africa. In Sustainable Human Resource Management in Tourism (pp. 77–92). Springer Nature. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressan, A., & Pedrini, M. (2020). Exploring sustainable-oriented innovation within micro and small tourism firms. Tourism Planning and Development, 17(5), 497–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buallay, A., Al-Ajmi, J., & Barone, E. (2022). Sustainability engagement’s impact on tourism sector performance: Linear and nonlinear models. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 35(2), 361–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bux, C., & Amicarelli, V. (2023). Circular economy and sustainable strategies in the hospitality industry: Current trends and empirical implications. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 23(4), 624–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calisto, M. de L., Umbelino, J., Gonçalves, A., & Viegas, C. (2021). Environmental sustainability strategies for smaller companies in the hotel industry: Doing the right thing or doing things right? Sustainability, 13(18), 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carasuk, R., Becken, S., & Hughey, K. F. D. (2016). Exploring values, drivers, and barriers as antecedents of implementing responsible tourism. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 40(1), 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzifoti, N., Chountalas, P. T., Agoraki, K. K., & Georgakellos, D. A. (2025). A DEMATEL based approach for evaluating critical success factors for knowledge management implementation: Evidence from the tourism accommodation sector. Knowledge, 5(1), 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chountalas, P. T., Chatzifoti, N., Alexandropoulou, A., & Georgakellos, D. A. (2024). Analyzing barriers to innovation management implementation in sustainable tourism using DEMATEL method. World, 5(4), 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cingoski, V., & Petrevska, B. (2018). Making hotels more energy efficient: The managerial perception. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 31(1), 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Farina, E., Díaz-Hernández, J. J., & Padrón-Fumero, N. (2025). A participatory waste policy reform for the hotel sector: Evidence of a progressive Pay-As-You-Throw tariff. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 33(4), 697–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dibra, M. (2015). Rogers theory on diffusion of innovation-the most appropriate theoretical model in the study of factors influencing the integration of sustainability in tourism businesses. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences, 195, 1453–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkhwesky, Z., El Manzani, Y., & Elbayoumi Salem, I. (2024). Driving hospitality and tourism to foster sustainable innovation: A systematic review of COVID-19-related studies and practical implications in the digital era. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 24(1), 115–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshaer, I. A., Azazz, A. M. S., & Fayyad, S. (2023). Green management and sustainable performance of small- and medium-sized hospitality businesses: Moderating the role of an employee’s pro-environmental behaviour. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(3), 2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esawe, A. T., Esawe, K. T., & Esawe, N. T. (2024). Impact of environmentally sustainable innovation practices on consumer resistance: The moderating role of value co-creation in eco-hotel enterprises. Consumer Behavior in Tourism and Hospitality, 19(1), 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esquivel, M. H., Vargas Martínez, E. E., Cruz, A. D., & Montes Hincapié, J. M. (2021). Sustainable innovation: Concepts and challenges for tourism organizations. Academica Turistica, 14(2), 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frleta, D. S., & Zupan, D. (2020). Zero waste concept in tourism. Economic and Social Development: Book of Proceedings, 157–167. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Venelin-Terziev/publication/340225475_Social_effectiveness_as_meter_in_the_development_of_social_economy/links/5e7dbba8a6fdcc139c08fb74/Social-effectiveness-as-meter-in-the-development-of-social-economy.pdf#page=166 (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Galeazzo, A., Ortiz-de-Mandojana, N., & Delgado-Ceballos, J. (2021). Green procurement and financial performance in the tourism industry: The moderating role of tourists’ green purchasing behaviour. Current Issues in Tourism, 24(5), 700–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, M., & León, C. J. (2001). The adoption of environmental innovations in the hotel industry of Gran Canaria. Tourism Economics, 7(2), 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graci, S. (2020). Collaboration and partnership development for sustainable tourism. In Tourism and sustainable development goals. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gruchmann, T., Topp, M., & Seeler, S. (2022). Sustainable supply chain management in tourism: A systematic literature review. Supply Chain Forum: An International Journal, 23(4), 329–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gül, H., Çağatay, S., & Gartner, W. C. (2025). Fossil fuel and resource use impacts of raw material substitution and recycling in tourism sector in Türkiye: Evidence from circular economy adjusted input-output matrix. Current Issues in Tourism, 28(15), 2480–2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürlek, M., & Koseoglu, M. A. (2021). Green innovation research in the field of hospitality and tourism: The construct, antecedents, consequences, and future outlook. The Service Industries Journal, 41(11–12), 734–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, A., & Pearson, L. J. (2018). Examining stakeholder group specificity: An innovative sustainable tourism approach. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 8, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjalager, A.-M. (1997). Innovation patterns in sustainable tourism: An analytical typology. Tourism Management, 18(1), 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horng, J.-S., Liu, C.-H., Chou, S.-F., Tsai, C.-Y., & Chung, Y.-C. (2017). From innovation to sustainability: Sustainability innovations of eco-friendly hotels in Taiwan. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 63, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S., & Soni, G. (2025). Sustainable waste management practices in the hospitality industry: Towards environmental responsibility and economic viability. In Sustainable waste management in the tourism and hospitality sectors (pp. 91–124). IGI Global Scientific Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M. F., Zhang, J., & Hasan, N. (2020). Assessing the adoption of sustainability practices in tourism industry. The Bottom Line, 33(1), 94–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO. (2015). Environmental management systems requirements with guidance for use (ISO 14001:2015). ISO.

- Jacob, M., Tintoré, J., Aguiló, E., Bravo, A., & Mulet, J. (2003). Innovation in the tourism sector: Results from a pilot study in the Balearic Islands. Tourism Economics, 9(3), 279–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, J., Malmström, M., & Wincent, J. (2021). Sustainable investments in responsible SMEs: That’s what’s distinguish government VCs from private VCs. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 14(1), 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juvan, E., Grün, B., & Dolnicar, S. (2023). Waste production patterns in hotels and restaurants: An intra-sectoral segmentation approach. Annals of Tourism Research Empirical Insights, 4(1), 100090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karvounidi, M. D., Alexandropoulou, A. P., & Fousteris, A. E. (2024). Towards sustainable hospitality: Enhancing energy efficiency in hotels. International Research Journal of Economics and Management Studies, 3(6), 410–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kernel, P. (2005). Creating and implementing a model for sustainable development in tourism enterprises. Journal of Cleaner Production, 13(2), 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kholijah, S. (2024). Analysis of economic and environmental benefits of green business practices in the hospitality and tourism sector. Involvement International Journal of Business, 1(1), 60–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivunja, C., & Kuyini, A. B. (2017). Understanding and applying research paradigms in educational contexts. International Journal of Higher Education, 6(5), 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobos, P. H., Drennen, T. E., Outkin, A. V., Webb, E. K., Paap, S. M., & Wiryadinata, S. (2020). Techno-economic analysis: Best practices and assessment tools. Sandia National Laboratories. Available online: https://www.osti.gov/biblio/1738878 (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- Kuo, F.-I., Fang, W.-T., & LePage, B. A. (2022). Proactive environmental strategies in the hotel industry: Eco-innovation, green competitive advantage, and green core competence. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 30(6), 1240–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitt, B., & March, J. G. (1988). Organizational learning. Annual Review of Sociology, 14(1), 319–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K., Cipolletta, G., Andreola, C., Eusebi, A. L., Kulaga, B., Cardinali, S., & Fatone, F. (2024). Circular economy and sustainability in the tourism industry: Critical analysis of integrated solutions and good practices in European and Chinese case studies. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 26(7), 16461–16482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L., Patwary, A. K., & Mengxiang, L. (2024). Measuring green performance in hotel industry through management environmental concern: Mediated by green product and process innovation. SAGE Open, 14(4), 21582440241255278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-W., & Cheng, J.-S. (2018). Exploring driving forces of innovation in the MSEs: The case of the sustainable B & B tourism industry. Sustainability, 10(11), 3983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Gamero, M. D., Molina-Azorín, J. F., Pereira-Moliner, J., & Pertusa-Ortega, E. M. (2023). Agility, innovation, environmental management and competitiveness in the hotel industry. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 30(2), 548–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manniche, J., Larsen, K. T., & Broegaard, R. B. (2021). The circular economy in tourism: Transition perspectives for business and research. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 21(3), 247–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masudin, I., Umamy, S. Z., Al-Imron, C. N., & Restuputri, D. P. (2022). Green procurement implementation through supplier selection: A bibliometric review. Cogent Engineering, 9(1), 2119686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menegaki, A. N. (2025). Optimizing pollution control in the hospitality sector: A theoretical framework for sustainable hotel operations. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(2), 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meneses, D., Costa, C., Ferreira, F. A., & Eusébio, C. (2024). Sustainability innovation in tourism: A systematic literature review. In A. L. Negrua, & M. M. Coros (Eds.), Springer proceedings in business and economics (pp. 45–66). Springer Nature. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montano, L. J., Elsenbroich, C., Font, X., & Ribeiro, M. A. (2024). Impact evaluation with process tracing: Explaining causal processes in an EU-interreg sustainable tourism intervention. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 33, 1752–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najda-Janoszka, M., & Kopera, S. (2014). Exploring barriers to innovation in tourism industry—The case of southern region of Poland. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences, 110, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesticò, A., & Maselli, G. (2020). Sustainability indicators for the economic evaluation of tourism investments on islands. Journal of Cleaner Production, 248, 119217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nocca, F., Bosone, M., De Toro, P., & Fusco Girard, L. (2023). Towards the human circular tourism: Recommendations, actions, and multidimensional indicators for the tourist category. Sustainability, 15(3), 1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pace, L. A. (2016). How do tourism firms innovate for sustainable energy consumption? A capabilities perspective on the adoption of energy efficiency in tourism accommodation establishments. Journal of Cleaner Production, 111, 409–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panfiluk, E. (2023). In search of innovation barriers to tourist destinations—Indications for organizations managing destinations. Sustainability, 15(2), 1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsa, H. G. (2015). Sustainability, social responsibility, and innovations in tourism and hospitality. Apple Academic Press. Available online: https://api.taylorfrancis.com/content/books/mono/download?identifierName=doi&identifierValue=10.1201/b18326&type=googlepdf (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- Patwa, A. (2024). Evaluating the economic and environmental impacts of comprehensive emission reduction strategies in SMEs: A case study approach. E3S Web of Conferences, 596, 01022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remenyik, B., Szőke, B., Veres, B., & Dávid, L. D. (2025). Innovative sustainability practices in ecotourism and the hotel industry: Insights into circular economy and community integration. Journal of Infrastructure, Policy and Development, 9(1), 10946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repáraz, C., & Pérez, J. C. (2024). Circular economy in the tourism sector. In P. Mora, & F. G. Acien Fernandez (Eds.), Circular economy on energy and natural resources industries: New processes and applications to reduce, reuse and recycle materials and decrease greenhouse gases emissions (pp. 151–166). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridder, H.-G. (2017). The theory contribution of case study research designs. Business Research, 10(2), 281–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robaina, M., & Madaleno, M. (2019). Resources: Eco-efficiency, sustainability and innovation in tourism. In E. Fayos-Solà, & C. Cooper (Eds.), The future of tourism: Innovation and sustainability (pp. 19–41). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Antón, J. M., & Alonso-Almeida, M. del M. (2019). The circular economy strategy in hospitality: A multicase approach. Sustainability, 11(20), 5665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Sánchez, I., Williams, A. M., & García Andreu, H. (2020). Customer resistance to tourism innovations: Entrepreneurs’ understanding and management strategies. Journal of Travel Research, 59(3), 450–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E. (2003). Diffusion of innovations (5th ed.). Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Roxas, F. M. Y., Rivera, J. P. R., & Gutierrez, E. L. M. (2020). Mapping stakeholders’ roles in governing sustainable tourism destinations. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 45, 387–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudan, E. (2023). Circular economy of cultural heritage—Possibility to create a new tourism product through adaptive reuse. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 16(3), 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakshi, Shashi, Cerchione, R., & Bansal, H. (2020). Measuring the impact of sustainability policy and practices in tourism and hospitality industry. Business Strategy and the Environment, 29(3), 1109–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, V., Sousa, M. J., Costa, C., & Au-Yong-oliveira, M. (2021). Tourism towards sustainability and innovation: A systematic literature review. Sustainability, 13(20), 11440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satta, G., Spinelli, R., & Parola, F. (2019). Is tourism going green? A literature review on green innovation for sustainable tourism. Tourism Analysis, 24(3), 265–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönherr, S., Eller, R., Kallmuenzer, A., & Peters, M. (2023). Organisational learning and sustainable tourism: The enabling role of digital transformation. Journal of Knowledge Management, 27(11), 82–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, M., Pradhan, S., & Ranajee. (2019). Sampling in qualitative research. In Qualitative techniques for workplace data analysis (pp. 25–51). IGI Global Scientific Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, J. F., Bilsky, B. A., & Shelleman, J. M. (2024). SMEs, sustainability, and capital budgeting. Small Business Institute Journal, 20(1), 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singal, M. (2014). The link between firm financial performance and investment in sustainability initiatives. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 55(1), 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A. B., Mishra, Y., & Yadav, S. (2024). Toward sustainability: Interventions for implementing energy-efficient systems into hotel buildings. Engineering Proceedings, 67(1), 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smerecnik, K. R., & Andersen, P. A. (2011). The diffusion of environmental sustainability innovations in North American hotels and ski resorts. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 19(2), 171–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q., Li, J., & Zeng, X. (2015). Minimizing the increasing solid waste through zero waste strategy. Journal of Cleaner Production, 104, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovani, A. H. (2022). What innovations would enable the tourism and hospitality industry in the European Union to re-build? Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes, 14(6), 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, F., & Bærenholdt, J. O. (2020). Tourist practices in the circular economy. Annals of Tourism Research, 85, 103027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stake, R. E. (2005). Qualitative case studies. In The Sage handbook of qualitative research (3rd ed., pp. 443–466). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Stanovčić, T., Peković, S., Vukčević, J., & Perović, Đ. (2018). Going entrepreneurial: Agro-tourism and rural development in Northern Montenegro. Business Systems Research: International Journal of the Society for Advancing Innovation and Research in Economy, 9(1), 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylos, N., Fotiadis, A. K., Shin, D. D., & Huan, T.-C. T. (2021). Beyond smart systems adoption: Enabling diffusion and assimilation of smartness in hospitality. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 98, 103042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y., Ding, W., & Yang, G. (2022). Green innovation efficiency of China’s tourism industry from the perspective of shared inputs: Dynamic evolution and combination improvement paths. Ecological Indicators, 138, 108824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suno Wu, J., Font, X., Barbrook-Johnson, P., & Torres Delgado, A. (2025). Social learning communities of practice as mechanisms for sustainable tourism: A process tracing evaluation of a government intervention. Tourism Recreation Research, 50(3), 521–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SWITCH-Asia. (2025). The missing link: Unlocking sustainable tourism through green procurement. SWITCH-Asia. Available online: https://www.switch-asia.eu/resource/the-missing-link-unlocking-sustainable-tourism-through-green-procurement/ (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Tansel, T., Yeshenkulova, G., & Nurmanova, U. (2021). Analysing waste management and recycling practices for the hotel industry. Journal of Environmental Management & Tourism, 12(2), 382–391. [Google Scholar]

- Trišić, I., Štetić, S., & Vujović, S. (2021). The importance of green procurement and responsible economy for sustainable tourism development: Hospitality of Serbia. Ekonomika Preduzeća, 69(7–8), 450–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzschentke, N. A., Kirk, D., & Lynch, P. A. (2008). Going green: Decisional factors in small hospitality operations. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 27(1), 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallone, C., Orlandini, P., & Cecchetti, R. (2013). Sustainability and innovation in tourism services: The Albergo Diffuso case study. Eurasian Journal of Social Sciences, 1(2), 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L., Song, H., Yang, Y., & Han, M. (2024). A systematic literature review and bibliometric analysis of green procurement. Kybernetes. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z., Zhang, L., Jiang, C., Xiao, C., Wang, L., Hu, W., & Yu, M. (2021). On the use of techno-economic evaluation on typical integrated energy technologies matching different companies. The Journal of Engineering, 2021(9), 534–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, C., Becken, S., & Coghlan, A. (2018). Sustainability-oriented service innovation: Fourteen-year longitudinal case study of a tourist accommodation provider. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 26(10), 1784–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R. K. (2014). Case study research: Design and methods (5th ed.). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Zografakis, N., Gillas, K., Pollaki, A., Profylienou, M., Bounialetou, F., & Tsagarakis, K. P. (2011). Assessment of practices and technologies of energy saving and renewable energy sources in hotels in Crete. Renewable Energy, 36(5), 1323–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ID | Role | Department/Function | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | Owner (Father) | Founding/Executive oversight | Co-founder; involved in high-level decisions. |

| P2 | Owner (Daughter) | Operations & Sustainability Lead | Actively manages daily operations and eco-initiatives. |

| P3 | Manager | General Management | Oversees staff coordination and implementation. |

| P4 | Receptionist | Front Desk/Guest Services | Communicates green policies to guests. |

| P5 | Kitchen Assistant | Kitchen/Food Services | Handles organic waste and composting routines. |

| P6 | Housekeeping staff | Housekeeping | Involved in waste sorting and cleaning routines. |

| P7 | Local supplier | Produce Supplier | Provides organic produce to the hotel. |

| P8 | Local supplier | Handcrafted Goods Supplier | Supplies sustainable goods for guest amenities. |

| Year | Main Intervention (Innovation) | Intermediate Steps/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 2018 | Installation of solar collectors | Pilot implementation in the main building; staff trained in the operation of new systems. |

| 2019 | Launch of composting program | Distribution of compost bins; awareness and training activities on proper organic waste separation. |

| 2020–2021 | Adjustments and preparation | Temporary suspension of composting due to COVID-19; supplier changes to reduce waste; improvements in waste collection infrastructure and procedures |

| 2022–2024 | Zero waste partnerships | Collaboration with an external zero waste partner; integration into a circular economy network; community awareness initiatives |

| Indicators | Before | After | Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Financial: | |||

| Annual energy cost (€) | 21,500 | 16,600 | −23% |

| Annual water cost (€) | 2160 | 1800 | −17% |

| Environmental: | |||

| Energy use per overnight (kWh) | 12 | 8.5 | −29% |

| Water use per overnight (liters) | 180 | 140 | −22% |

| Waste to landfill (tons/year) | 9.5 | 5.1 | −46% |

| Certifications | 0 | ISO 14001 | +1 |

| Operational: | |||

| Average occupancy (%) | 70% | 85% | +15% |

| Average stay duration (nights/booking) | 3.5 | 4.3 | +23% |

| Staff training in sustainable practices (hours/year) | 0 | 40 | +40 |

| Local suppliers | 3 | 7 | +4 |

| Experiential: | |||

| Customer satisfaction (Booking.com, 1–10) | 8.6 | 9.3 | +0.7 |

| Repeat guest rate (estimated %) | 15% | 25% | +10% |

| Implementation Costs (€): | |||

| Solar and thermal systems | 36,000 | ||

| Composting equipment | 3500 | ||

| Water-saving and LED systems | 2200 | ||

| Staff training | 800 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chatzifoti, N.; Alexandropoulou, A.; Fousteris, A.E.; Karvounidi, M.D.; Chountalas, P.T. Techno-Economic Evaluation of Sustainability Innovations in a Tourism SME: A Process-Tracing Study. Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 209. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6040209

Chatzifoti N, Alexandropoulou A, Fousteris AE, Karvounidi MD, Chountalas PT. Techno-Economic Evaluation of Sustainability Innovations in a Tourism SME: A Process-Tracing Study. Tourism and Hospitality. 2025; 6(4):209. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6040209

Chicago/Turabian StyleChatzifoti, Natalia, Alexandra Alexandropoulou, Andreas E. Fousteris, Maria D. Karvounidi, and Panos T. Chountalas. 2025. "Techno-Economic Evaluation of Sustainability Innovations in a Tourism SME: A Process-Tracing Study" Tourism and Hospitality 6, no. 4: 209. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6040209

APA StyleChatzifoti, N., Alexandropoulou, A., Fousteris, A. E., Karvounidi, M. D., & Chountalas, P. T. (2025). Techno-Economic Evaluation of Sustainability Innovations in a Tourism SME: A Process-Tracing Study. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(4), 209. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6040209