Abstract

This study examines the accessibility of tourism facilities in the Banská Bystrica region of Slovakia for visitors with disabilities and explores the attitudes of service providers toward inclusive tourism. Accessibility remains a key challenge in developing equitable tourism services, and this research aims to evaluate the current state of barrier-free infrastructure while identifying opportunities for improvement. A survey of 45 tourism facilities was conducted to assess compliance with accessibility standards, revealing that only 22.22% of the facilities meet the required criteria. To complement these findings, structured interviews with representatives from eight facilities were carried out, with responses analyzed using ATLAS.ti software (Version 24.0.0) to visualize patterns through diagrams and Sankey networks. The results highlight significant shortcomings in physical accessibility as well as mixed attitudes of service providers toward the needs of disabled visitors. The study concludes that while awareness of inclusive practices is growing, substantial efforts are still required to improve infrastructure and foster positive engagement from service providers. These findings provide valuable insights for policymakers, tourism stakeholders, and service operators, offering practical recommendations for enhancing accessibility and promoting a more inclusive tourism environment in the region.

1. Introduction

Tourism plays a vital role in social inclusion by providing opportunities for participation, interaction, and personal development. However, for people with disabilities, access to tourism services remains uneven, with persistent physical, social, and attitudinal barriers limiting equal participation. The global increase in disability prevalence, driven by factors such as ageing populations, chronic illnesses, injuries, and congenital conditions, underscores the importance of adapting tourism systems to meet diverse needs (Buhalis et al., 2012). Research shows that disabled visitors often face exclusion from mainstream tourism services and require tailored products and infrastructure to ensure their integration into society (Linderová & Janeček, 2017; Rubio-Escuderos et al., 2021). While some studies emphasize the economic costs of disability and the need for specialized care, others highlight the aspirations of disabled individuals to be recognized as equal members of society (Marčeková & Šebová, 2020).

Participation in tourism brings clear benefits, including enhanced quality of life, opportunities for recovery, social integration, and psychological well-being (Kastenholz et al., 2015). International organizations stress the importance of inclusivity, with the United Nations identifying it as a key principle of sustainable development (UNDP, 2016) and the UNWTO promoting accessible tourism as a fundamental right (UNWTO, 2018; Gillovic & McIntosh, 2020). The literature distinguishes between social tourism, which provides opportunities for disadvantaged groups such as seniors, youth, low-income families, and disabled people (Minnaert et al., 2009), and accessible tourism, which focuses on enabling independent, barrier-free travel for people with disabilities and other groups requiring support (Buhalis & Darcy, 2010; Diekmann et al., 2011). Although both concepts share the goal of equality, debates remain regarding whether accessibility should be approached primarily through infrastructure and regulation or through stakeholder engagement and cultural change (Nyanjom et al., 2018).

Against this backdrop, the present case study examines the accessibility of tourism facilities in the Banská Bystrica region of Slovakia, the country’s largest and geographically diverse region with a rich natural and cultural heritage. The Banská Bystrica region, located in central Slovakia, constitutes one of the country’s most diverse and multifaceted tourism destinations. The region’s geographical position encompasses several mountain ranges, including the Low Tatras, Veľká Fatra, and Štiavnické vrchy, which provide opportunities for year-round recreational activities such as hiking, skiing, and nature-based tourism. At the same time, the region is distinguished by its rich cultural and historical heritage, with notable urban centres such as Banská Bystrica, Banská Štiavnica, and Zvolen offering a wealth of architectural monuments, museums, and cultural institutions. The UNESCO-listed town of Banská Štiavnica represents a focal point of heritage tourism. These natural and cultural assets, combined with local traditions, gastronomy, and spa resorts, form a solid foundation for the development of a competitive and resilient tourism sector.

Tourism in the region is supported by a relatively well-developed infrastructure, comprising accommodation establishments of varying standards, catering facilities, and tourist information centres. The presence of seasonal events, cultural festivals, and outdoor sports activities further enhances the attractiveness of the region, making it a destination for both short-term domestic trips and longer international stays. Nevertheless, the tourism industry is highly dependent on domestic demand, which continues to represent the dominant share of visitor flows.

In 2024, the Banská Bystrica region reported a total of 667,009 visitors accommodated in tourism establishments (Statistical Office of the Slovak Republic, 2024). This figure underscores the continuing importance of tourism for the regional economy and demonstrates the region’s ability to attract significant numbers of visitors in a competitive national and international context.

According to the Statistical Office of the Slovak Republic (Statistical Office of the Slovak Republic, 2024), approximately 830 accommodation establishments were in operation across the region in 2024. These generated an estimated €75 million in revenue, confirming the sector’s substantial contribution to the regional economy. Tourism not only provides direct financial benefits through accommodation and related services but also generates secondary effects through increased demand in sectors such as gastronomy, transport, retail, and cultural activities.

The study aims to assess the level of adaptation of tourism facilities for visitors with disabilities and to evaluate the attitudes of service providers toward inclusive practices. By combining a facility survey with qualitative interviews, the research provides insights into both structural and attitudinal barriers. The findings highlight key areas for improvement and offer recommendations to enhance inclusive tourism practices, contributing to ongoing discussions about equality, accessibility, and sustainable regional development.

2. Theoretical Background

Disability represents a universal social reality that no society can entirely evade. It is frequently linked with disadvantages in areas such as communication, social relationships, and integration into community life (Kollarová & Kollar, 2010; Faizefu & Neba, 2024). Consequently, individuals with disabilities are often subject to discrimination and encounter major obstacles when seeking access to healthcare, education, employment, or even ordinary leisure opportunities (European Commission, 2021; Sarkar & Parween, 2021). Beyond these challenges, additional financial burdens arise for both disabled people and their families, including expenses related to medical treatment, assistive technologies, personal assistance, transport, or specialist nutrition (Mitra et al., 2017; Warren et al., 2023). Such costs vary according to the type and severity of disability, life stage, and household circumstances (Mitra et al., 2017) and are widely recognised as important drivers of social exclusion (Haluwalia et al., 2022; Önal et al., 2024).

Travel is widely regarded as an essential human activity, and research indicates that people with disabilities often demonstrate stronger motivation to travel and, in some contexts, travel more frequently than the general population (Gonda, 2021). Like other tourists, this group is motivated by a desire to explore, relax, socialise, gain knowledge, and achieve personal fulfillment (Eusébio et al., 2023). Engagement in tourism can also contribute to education and cultural capital, thereby influencing social standing (Gúčik, 2020). Moreover, travel facilitates inclusion (Załuska et al., 2022), personal development through exposure to new environments, cultures, and activities, as well as improved health and well-being (ISTO, 2011). It is further associated with increased happiness and an enhanced quality of life (Gonda et al., 2019). Moura et al. (2022) also argue that creating opportunities for disabled travellers is vital, as participation in tourism supports both well-being and personal growth.

Due to global demographic ageing, people with disabilities represent a growing tourism market segment (Linderová, 2016). Gonda (2021, 2024) contends that significant advances in accessibility would generate exponential growth in demand, since more differentiated products can open the sector to socially disadvantaged groups. This presents not only a social imperative but also a business opportunity, particularly through innovative practices (Zenko & Sardi, 2014). Empirical studies indicate that disabled tourists often show higher levels of loyalty, return to destinations that meet their accessibility needs, and typically stay longer and travel with companions, thereby generating economic multipliers (Luiza, 2010; Domínguez et al., 2013; Linderová, 2015; Linderová & Janeček, 2017). Furthermore, they frequently spend more per day and seek a wider range of services, which can stimulate local economies. A service chain tailored to their requirements can foster growth, employment, and competitiveness (Agovino et al., 2017; Kučera & Gavurová, 2020; Santana-Santana et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2023). Linderová (2015) additionally notes that debarrierisation supports local production and generates employment in both tourism and related sectors. Enhanced accessibility also contributes to corporate social responsibility, strengthens the reputation of cultural sites (Kovačić et al., 2024), and improves the overall quality of services and visitor experiences (Liu et al., 2023). Accessibility is further correlated with visitor satisfaction (Leiras & Eusébio, 2023).

Although accessibility measures are primarily intended to benefit disabled people, they also yield advantages for the wider population by enhancing safety and overall destination appeal (Marčeková & Šebová, 2020; Frye, 2015). Hence, accessibility is a prerequisite not only for the social inclusion of individuals with special needs but also for unlocking significant economic potential (Agovino et al., 2017). Nevertheless, negative side effects of debarrierisation have also been identified, such as reduced parking capacity, overcrowding, noise, crime, and environmental pressures (Linderová, 2015).

Despite the evident enthusiasm of disabled people for travel, their participation is often constrained by barriers that affect their motivations, needs, and satisfaction, rendering them more selective (Gassiot et al., 2018; Perangin-Angin et al., 2023). Scholars have categorised such barriers differently: Reyes-García et al. (2021) emphasise physical, sensory, and cognitive obstacles, while Linderová (2016) highlights architectural, social, and economic barriers on the supply side. Buhalis and Darcy (2010) instead stress the role of information deficits and the inaccessibility of information itself. Crawford et al. (1991) proposed a hierarchical model of intrapersonal, interpersonal, and structural barriers, which has also been endorsed by more recent authors (Eusébio et al., 2023; Hefny, 2024). According to Fuchs (2024), barriers to accessible tourism are most visible in airports, accommodation, transport networks, recreation, and health and wellness services.

Understanding the needs of disabled visitors is therefore crucial to any attempt to enhance their quality of life (Stankova et al., 2021). Tailoring tourism products and services to such preferences is a key condition for inclusivity (Závodi et al., 2021). Cultural heritage institutions, museums, and galleries are increasingly adopting accessibility strategies (Mastrogiuseppe et al., 2021). However, scholars such as Hanko (2015) and Kovačić et al. (2024) argue that global trends and emerging challenges necessitate greater adaptation to the requirements of a diverse audience. Other studies confirm that ensuring accessibility of cultural attractions requires holistic, systematic approaches (Andani et al., 2013; Koustriava & Koutsmani, 2023; Partarakis et al., 2016; Leahy & Ferri, 2023). According to the UNWTO (2013), organisations responsible for cultural sites must adopt measures that enable people with disabilities to participate fully and realise their creative, artistic, and intellectual potential for the benefit of society as a whole.

Assessing the current level of accessibility is also essential for identifying solutions (Naniopoulos & Tsalis, 2015). The UNWTO (2023) recommends alignment with international benchmarks such as ISO Standard 21902. However, reconciling accessibility with heritage conservation remains challenging (Andani et al., 2013; Linderová, 2016). More recent buildings are generally more accessible than listed heritage sites (Koustriava & Koutsmani, 2023). Despite progress in policy and practice, preservation priorities often outweigh accessibility (Plimmer et al., 2006). Scholars such as Naniopoulos and Tsalis (2015) and Lynch and Proverbs (2020) therefore call for strategies that balance accessibility with the safeguarding of cultural value.

The extent of accessibility is also linked to a country’s overall development (Kovačić et al., 2024). Despite higher prevalence of disability in developing countries, accessibility remains weaker (Marsin et al., 2014; Reyes-García et al., 2021). Museum attendance is another factor, as institutions with higher visitor numbers tend to invest more in accessibility (Kruczek et al., 2024). Barriers to progress include financing, insufficient training, limited motivation, public resistance, and tensions between accessibility measures and business priorities (Lynch & Proverbs, 2020).

3. Materials and Methods

The aim of this case study is to assess the level of adaptation of tourism facilities in the Banská Bystrica region for visitors with disabilities and to evaluate current initiatives undertaken by these entities to provide a comprehensive inclusive tourism experience.

The primary source of data on the adaptation of tourism offerings was obtained through a survey. The survey was conducted online using an electronic questionnaire (Google Forms) and distributed via email communication between October and December 2023. The questionnaire consisted of twenty-nine questions and focused on aspects of tourism offerings and the extent of their adaptation. It comprised items grouped into thematic blocks covering different dimensions of accessibility and inclusive service provision.

The first set of questions (Q1–Q4) identified the basic characteristics of the facility (type, category, and overall level of accessibility). Facilities indicating partial accessibility were asked to specify which parts of their infrastructure were adapted.

The next block (Q5–Q10) focused on the availability of accessibility features, including designated parking, barrier-free entrances and sanitary facilities, and whether adaptations were natural or required structural modifications. Respondents also reported on specific measures (e.g., ramps, elevators, Braille, induction loops) and indicated which visitor groups they targeted (mobility, visual or hearing impairments, intellectual disabilities, seniors, children, pregnant women).

Questions Q11–Q18 examined barriers and organisational aspects such as reasons for not adapting (financial, organisational, spatial, informational), the estimated share of visitors with limitations, staff training levels, inclusion of employees with disabilities, the availability of accessibility information online, and whether assistance animals were permitted.

The subsequent section (Q19–Q25) addressed the financial and informational dimension, including initial and maintenance costs of adaptations, use of subsidies or EU funds, tools for improving accessibility, the presence of pictograms and signage, disadvantaged groups using the facilities, and the main age groups of visitors.

Finally, Q26–Q29 considered visitor demand and further cooperation, asking how often guests enquired about accessibility, and whether operators were willing to participate in follow-up interviews.

This comprehensive structure allowed the survey to capture both the structural and organisational aspects of accessibility, offering a multi-layered view of current practices, barriers, and opportunities in the Banská Bystrica region.

The sample included tourism facilities within the Banská Bystrica region selected using a convenience sampling method. The outreach phase targeted all accommodation establishments, cultural institutions, tourist information centres, and catering facilities situated within the Banská Bystrica region. These entities were identified through publicly accessible databases, including the official website of the Banská Bystrica Self-Governing Region, regional tourism organisations, municipal information portals, and specialised online platforms focusing on tourism, accommodation, and catering services. Invitations to participate in the survey were distributed via the publicly available email addresses of these facilities. Participation was entirely voluntary, and only those institutions willing to complete the questionnaire were included in the final dataset, reflecting a form of self-selection within the sample (Etikan et al., 2016).

It should be emphasised that the survey was not directed at specific employees but rather at the operators or managers of the respective facilities. Consequently, it was neither necessary nor methodologically appropriate to examine the demographic characteristics of respondents, nor to investigate their formal positions within the organisational hierarchy. Respondents were treated solely as representatives of the facilities they managed, thereby aligning with a unit-of-analysis approach commonly used in organisational and tourism research (Bryman, 2016).

The questionnaire also incorporated an optional item whereby respondents could provide a contact telephone number if the facility, through its operator, expressed interest in participating in a subsequent in-depth interview. Participation in the survey was voluntary, and respondents answered all questions. A total of 45 facilities participated in the survey, encompassing both primary and secondary tourism offerings. Museums accounted for the largest share of operations, representing 24.44% (Table 1).

Table 1.

Types of Tourism Facilities. Source: Marčeková et al. (2024).

The collected data were analyzed using descriptive statistics in MS Excel (Version 2508). The survey was complemented by an examination of the attitudes of selected facility operators that participated in the questionnaire and agreed to be contacted for in-depth interviews, either in person or by phone. We employed the interview method using a structured interview technique.

A total of 27 selected facility operators in the Banská Bystrica region were invited to participate in the interviews, of which 8 representatives consented. The survey was conducted either in person or by telephone from 29 February 2024, to 11 March 2024. Each interview lasted approximately 15–20 min (Table 2). During interviews with facility operators, consent was obtained for the inclusion and publication of their establishments within the context of academic publishing.

Table 2.

Surveyed Facilities.

The interviews were conducted to examine the attitudes toward the needs of disabled visitors. The results from the interviews were processed using ATLAS.ti software, which is designed for the analysis of qualitative data. In working with ATLAS.ti, we utilized Sankey diagrams and Networks to visually represent the responses of the facility operators. Since the research sample is potentially not representative, the survey results are illustrative in nature.

4. Results and Discussion

The results are divided into two parts. The first part focuses on the accessibility of tourism facilities in the Banská Bystrica region. The second part analyzes the attitudes of selected operators toward people with disabilities.

4.1. Accessibility of Tourism Facilities in Banská Bystrica Region

We investigated the accessibility of 45 tourism facilities in the Banská Bystrica region from the perspective of their operators. More than half of the tourism facilities have already taken steps toward accessibility, with 42.22% being partially accessible and 22.22% fully accessible. Facilities that are fully accessible have been thoroughly adapted to ensure their use is easy, comfortable, and safe for all visitors. This includes providing physical accessibility features such as barrier-free entrances without steps, equipped with ramps or elevators that enable wheelchair users to move freely; doors wide enough to accommodate wheelchairs; elevators with control panels positioned at heights accessible to wheelchair users; unobstructed sidewalks, corridors, and spaces that are sufficiently wide and equipped with non-slip surfaces; adapted restrooms with grab bars, non-slip flooring, and ample maneuvering space; and accessible reception areas and services with lowered counters. Additionally, these facilities provide signage in Braille for visually impaired individuals, as well as acoustic systems or visual indicators for those with hearing impairments. Such facilities also ensure communication accessibility, evacuation plans, and emergency exits that are accessible to people with limited mobility, alongside well-lit and safe environments. This indicates significant efforts by these enterprises to create an accessible environment for all visitors, including those with disabilities. A partially accessible facility is one that has implemented certain modifications aimed at improving accessibility but does not yet offer full barrier-free access.

However, 35.56% of the tourism facilities, more than one-third, remain inaccessible, primarily due to their historic buildings.

Out of the total of 45 facilities, only 15.60% provide designated parking spaces for individuals with a blue card and curb ramps, while 84.40% do not offer such spaces. Only 2.20% of the enterprises have parking spaces for mothers with strollers, while the remaining 97.80% lack such spaces.

Furthermore, we examined which areas of the tourism facilities are classified as accessible. The most frequently accessible area is the entrance hall (doors, elevators, lifts), which is accessible in 38.00% of cases. The second most common accessible area is the sanitary facilities, such as accessible restrooms with appropriate dimensions, handrails, and other adjustments. The ground floor is accessible in 4.00% of tourism facilities. Other accessible areas include gateways (2.22%), gardens (2.22%), restaurants (2.22%), and stair lifts (2.22%). 28.00% of enterprises have no accessible areas.

In 46.15% of cases, tourism facilities are naturally accessible, while 51.29% of tourism facilities had to undergo construction modifications to achieve accessibility. In 2.56% of tourism facilities, no construction modifications had been made yet.

We also examined the reasons why some tourism facilities have not made adjustments for visitors. The most common reason (33.90%) is financial constraints, which prevent the implementation of accessibility measures. For these facilities, investments in such adjustments are often financially burdensome, highlighting the need for various financial support and incentives to promote more inclusive tourism infrastructure. Other factors include organizational (15.25%) and spatial limitations (27.12%). 10.17% of tourism facilities are located in historic buildings, where it is necessary to request permission for reconstruction and modifications from the Regional Heritage Office. Some facilities (13.56%) did not specify the reasons.

Table 3 summarizes the overview of the target groups for which the spaces of tourism facilities in the Banská Bystrica region are being adapted. Facilities could select multiple options. The lowest number of facilities are adapted for people with intellectual disabilities for several reasons. The first is the lack of awareness about the specific needs of this group. Intellectual disabilities are less visible than other forms of disabilities, which may lead to less engagement from businesses in adapting their facilities. People with intellectual disabilities often require more flexible and individualized adjustments, which can be challenging to implement. Another factor is the economic cost of adaptations. Facilities for this group may require specialized technologies, staff training, or simplified communication methods, which can be perceived as expensive, especially when businesses consider the number of potential users to be low. Legislative and political factors also play a role. Although inclusion laws exist, intellectual disabilities often receive less attention than other forms of disability, leading to less motivation for businesses to adapt to this group. Social stigma and prejudice against people with intellectual disabilities further reduces the willingness to adapt facilities for this group, contributing to their marginalization in society.

Table 3.

Target Group in Terms of Facility and Equipment Adaptation. Source: Marčeková et al. (2024).

People with disabilities are not only concerned with the accessibility of facilities but also with whether the staff knows how to assist them. The survey reveals that only 20% of facilities have trained staff to help individuals with specific needs, which is alarming since 80% of facilities do not provide staff training. Proper training enhances service quality, improves visitor satisfaction, and helps employees feel more confident.

Most facilities (75%) have trained only 0–10% of their staff, 6.25% of facilities have trained 11–20% of their staff, and 18.75% have no trained staff members. Interestingly, only 26.67% of facilities employ people with specific needs, mostly with hearing or mobility impairments.

Information about accessibility on websites is crucial for decision-making for visitors with disabilities. As many as 79.10% of facilities do not publish this information, which can lead to the loss of potential visitors.

Guide dogs and service animals are key helpers for people with disabilities. Unfortunately, only 23.30% of facilities allow the entry of service animals, highlighting the need to improve accessibility in this regard. Facilities should regard these animals as vital companions who profoundly improve the quality of life for many visitors with disabilities.

There are several tools that improve the accessibility of facilities. Table 4 displays the tools used in the studied facilities.

Table 4.

Tools Used to Improve Accessibility in Facilities. Source: Marčeková et al. (2024).

Pictograms can be a valuable tool for individuals with disabilities, helping them with communication and orientation. In facilities, they can indicate restrooms, elevators, warning signs for people with visual impairments, the hearing-impaired, and others. Despite their usefulness, only 9.30% of facilities use pictograms, 23.30% use them partially, while 67.40% of facilities do not use pictograms at all.

The survey revealed that facilities are most commonly visited by seniors and children (15.93%), mothers with strollers (15.49%), pregnant women (14.16%), and people with reduced mobility (14.16%). Less represented are individuals with mental (7.52%), hearing (6.19%), and visual impairments (5.75%), as well as those with dietary restrictions (4.85%).

This survey shows that facilities attract a diverse range of disadvantaged visitors, indicating the requirement to accommodate various needs. Facilities that choose to adapt their services for people with disabilities can potentially achieve higher revenues and improve their competitive position in the market. Active inclusion in tourism is not only an ethical step but also an opportunity for growth and profit. Although the initial investments in making spaces accessible may be high, once a facility becomes barrier-free, it suddenly becomes available to a much wider range of visitor groups and generally more attractive to the public. This increased accessibility is likely to lead to higher demand for such spaces, making the investment economically justifiable in the long term.

4.2. The Attitude of Facility Operators Towards Visitors with Disabilities

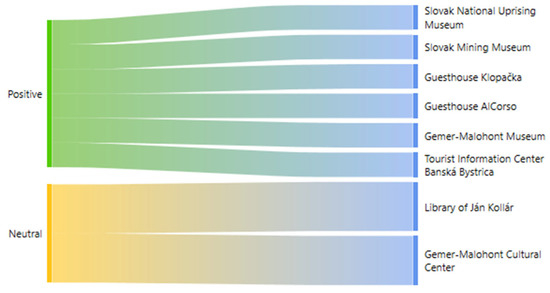

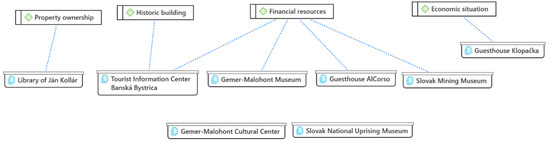

The contacted facility operators were grouped based on how they perceive the needs of physically, hearing, and visually impaired visitors, as well as their attitudes towards these groups. The responses were divided into two groups based on their willingness to accommodate these visitors (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Attitudes of Selected Facility Operators Toward Visitors with Disabilities. (Source: Own processing in ATLAS.ti, 2024).

The first group consists of facility operators with a positive attitude towards visitors with disabilities, meaning they actively strive to adjust their offerings and accommodate people with disabilities. This group includes the Slovak Mining Museum, Slovak National Uprising Museum, Tourist Information Center Banská Bystrica, Gemer-Malohont Museum, Guesthouse Klopačka, and Guesthouse AlCorso. The second group includes facility operators with a neutral attitude, who are aware of the needs of visitors with disabilities but, for various reasons, are unable to modify their offerings. This group includes the Library of Ján Kollár and the Gemer-Malohont Cultural Center. It is worth noting that none of the contacted facility operators had a negative attitude towards visitors with disabilities.

The facility operator of The Slovak National Uprising Museum, in an interview, expressed a clear stance that strongly supports the removal of barriers to cultural and educational facilities: “It is very important to transform a public institution, such as a museum, into a safe space adapted to the needs of people with disabilities, where they will have the same opportunities as those without disabilities. Therefore, it is necessary to focus primarily on debarrierization, eliminating any external obstacles that might affect the museum visit and reduce or even prevent the quality of experience for people with disabilities.”

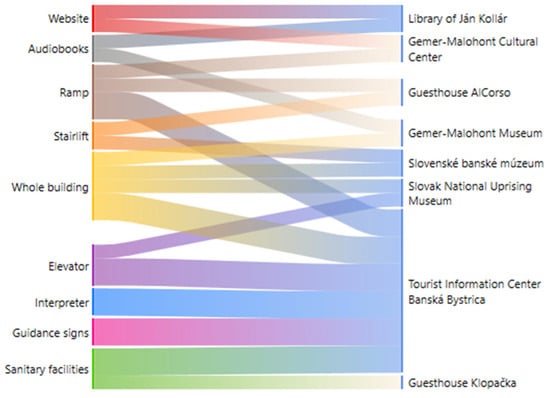

We were interested in the specific adaptations that the selected facilities have already implemented. The Slovak National Uprising Museum has fully adapted its entire building for visitors with disabilities, meaning all exhibits are wheelchair accessible, and visitors have access to an elevator. The Tourist Information Center in Banská Bystrica, among the facilities surveyed, is the most adapted to welcome visitors with disabilities. It has an elevator, and the entire town hall building in which it is located is equipped with tactile signage on the walls to aid visually impaired visitors in navigation. Additionally, the center offers accessible restrooms, a ramp, a stairlift, and online interpreters available through an application for hearing-impaired visitors (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Specific Types of Adaptations in Selected Facilities. (Source: Own processing in ATLAS.ti, 2024).

The Slovak Mining Museum also has a fully accessible building, including accessible restrooms, a stairlift, and a ramp. The Guesthouse Klopačka has an accessible restroom. The Guesthouse AlCorso has a stairlift and a ramp. The Gemer-Malohont Cultural Center has adapted its website for visually impaired visitors and has a ramp and accessible restrooms for visitors with mobility impairments. The Ján Kollár Library offers audiobooks and an accessible website for visually impaired visitors. The Gemer-Malohont Museum also offers audiobooks.

We were interested in whether the facilities employ a staff member responsible for communication with visitors with disabilities and for deciding what changes will be made and when. Seven of the surveyed facility operators (Guesthouse AlCorso, Guesthouse Klopačka, Slovak Mining Museum, Gemer-Malohont Cultural Center, Ján Kollár Library, Tourist Information Center Banská Bystrica, and Gemer-Malohont Museum) responded that they do not have such an employee, and communication with visitors with disabilities and their requirements is managed by all staff members. The operator of the Slovak National Uprising Museum was the only one to respond positively, as it has staff members in the education department responsible for communication and work with visitors with disabilities. These employees are museum educators who follow principles and guidelines for working and communicating with people with disabilities, providing assistance when needed. They have completed a museology course, which included thematic meetings on methodologies for working with visitors with specific needs. Based on their practical experience, they are also invited as consultants in the planned adjustments to the interior and exterior of the museum, where they can propose specific improvements (Table 5).

Table 5.

Responsible Person for Communication with Visitors with Disabilities.

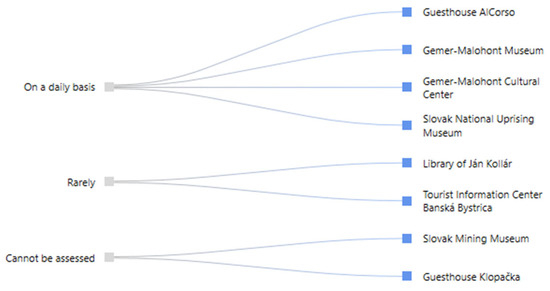

Visitors with disabilities rarely visit the Ján Kollár Library, the Gemer-Malohont Cultural Center, and the Tourist Information Center Banská Bystrica, and in the case of the Tourist Information Center, they usually visit with a companion. In the case of the Slovak Mining Museum and Guesthouse Klopačka, the surveyed individuals were unable to assess the frequency of visits by guests with disabilities. The Slovak National Uprising Museum, Guesthouse AlCorso, and Gemer-Malohont Museum are visited daily by people with disabilities (Figure 3). The Slovak National Uprising Museum stated: “The Slovak National Uprising Museum is visited relatively frequently by visitors with disabilities. Whether we are talking about mentally or physically disabled groups, they come regularly and are very welcome visitors, to whom we approach specifically, taking their needs into account.” Similarly, the Gemer-Malohont Museum responded positively: “People with disabilities are part of our visitor spectrum. For example, the most recent visitors to the museum were a daytime care center (for children and youth) from Rimavská Sobota, when children with physical and mental disabilities, and some with both, visited.”

Figure 3.

Frequency of Visits by Visitors with Disabilities. (Source: Own processing in ATLAS.ti, 2024).

The operators of the Slovak Mining Museum, Slovak National Uprising Museum, Gemer-Malohont Museum, Guesthouse AlCorso, and the Tourist Information Center Banská Bystrica consider it very important to gradually adapt their offerings for visitors with disabilities. Specifically, the operators of the Tourist Information Center and Guesthouse AlCorso stated that they view all visitors as equal, and for this reason, they consider it essential for everyone to have the same access to their spaces and services. The operators of Ján Kollár Library and Guesthouse Klopačka share a similar perspective, with Guesthouse Klopačka stating “The offering can always be adapted to benefit visitors with disabilities.” The operator of the Gemer-Malohont Cultural Center views the adaptation of offerings as less important, as they do not specifically specialize in these visitor segments and hold the opinion that sufficient changes have already been made in their favor (Table 6).

Table 6.

Perception of the Importance of Adapting the Offering for Visitors with Disabilities.

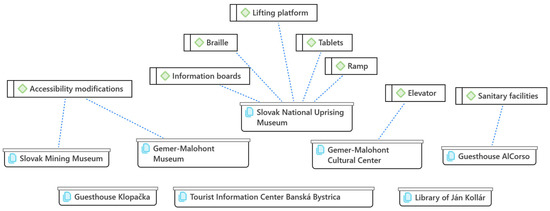

The operators of the Ján Kollár Library and Guesthouse Klopačka currently do not have clear plans for adapting their offerings for visitors with disabilities. The operator of the Tourist Information Center Banská Bystrica believes they have already done everything possible in their facilities. The operator of the Gemer-Malohont Cultural Center plans to install elevators to improve mobility for visitors with disabilities. The operator of the Guesthouse AlCorso plans to introduce barrier-free bathrooms throughout the guesthouse to improve comfort for visitors with disabilities. The operators of the Slovak Mining Museum and Gemer-Malohont Museum both plan to implement barrier-free changes to their spaces. While the operator of the Gemer-Malohont Museum plans to carry out overall barrier removal in both exhibition and non-exhibition areas, the operator of the Slovak Mining Museum already has already made its indoor exhibitions barrier-free and plans to innovate the surface exhibition of the Mining Museum in Nature in the near future to improve mobility for visitors with disabilities. The operator of the Slovak National Uprising Museum has the most plans, including the introduction of information boards, the use of Braille, tablets for hearing-impaired visitors, as well as ramps and lifting platforms to improve access and mobility for visitors with disabilities (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Planned Changes. (Source: Own processing in ATLAS.ti, 2024).

The most common reasons for not adapting spaces and offerings for visitors with disabilities include financial ones, as mentioned by the operators of the Tourist Information Center Banská Bystrica, Gemer-Malohont Museum, Slovak Mining Museum, and Guesthouse AlCorso. The operator of the Guesthouse Klopačka cited its economic situation as the reason. Another reason for the lack of adaptation at the Tourist Information Center Banská Bystrica is that it is located in a historic building, the Town Hall, and they are unable to make changes to their spaces at will. The operator of the Ján Kollár Library cites the fact that the spaces it occupies are not privately owned, which prevents them from making changes to their facilities, just like the tourist information centers (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Barriers Preventing the Adaptation of Spaces in Selected Facilities. (Source: Own processing in ATLAS.ti, 2024).

Based on the results obtained, we conclude that the majority of the studied facility operators are engaged in activities and proactive measures aimed at adapting their offerings for all visitors, including those with disabilities. Many of these operators perceive adapting their offerings for visitors with disabilities as an obligation. As stated in an interview by the Gemer-Malohont Cultural Center operator: “In the case of visitors to events with any form of disability, our goal is to eliminate obstacles as much as possible and, within our capabilities, skills, and best knowledge, provide all visitors with comparable services.”

It is important to acknowledge that the results of the structured interviews are largely consistent with the findings of the survey. Both data sources reveal that while some facilities have already implemented measures to improve accessibility, many still face significant financial and spatial barriers. Moreover, both the survey and interviews highlight a generally positive or neutral attitude of service providers toward visitors with disabilities, as well as a shared understanding of the importance of inclusion, despite practical constraints. This consistency between quantitative and qualitative findings strengthens the validity of the conclusions and demonstrates a coherent perspective among tourism stakeholders in the Banská Bystrica region.

5. Conclusions

In the Banská Bystrica region, the provision of services for visitors with disabilities remains a challenge due to financial, organizational, and spatial barriers. Many facilities are situated in historic buildings, where any modifications require approval from heritage authorities, further complicating efforts to improve accessibility. Although operators are generally aware of the need to adapt their offerings and express willingness to do so, these constraints often hinder meaningful progress.

In addition to physical adaptations, investment in staff training is essential for fostering an inclusive and welcoming environment in which all visitors, regardless of their abilities, feel equally accommodated. Enhancing accessibility not only improves the experience for visitors with disabilities but also contributes to the economic sustainability of tourism facilities by increasing their competitiveness and attracting a broader range of clientele. Inclusivity in tourism, therefore, represents not only an ethical imperative but also a strategic opportunity for sustainable growth and economic benefit.

The findings of this study are consistent with earlier research, which has emphasized that accessibility remains one of the least developed yet most impactful components of sustainable tourism development (Buhalis & Darcy, 2010; Linderová, 2015). Similar to studies conducted in other European contexts (Domínguez et al., 2013; Nyanjom et al., 2018), our results highlight the dual role of accessibility: on the one hand, as a condition for the social inclusion of disadvantaged groups, and on the other hand, as a driver of competitiveness and loyalty in tourism markets. The identified obstacles—particularly the tension between heritage preservation and modern accessibility standards—are also in line with the conclusions of previous work by Andani et al. (2013) and Koustriava and Koutsmani (2023), who underline the need for balanced solutions that respect both cultural value and inclusivity.

From the perspective of the working hypotheses, the research confirmed that despite a generally positive or neutral attitude of operators toward inclusive tourism, the absence of financial support and targeted policy instruments remains a decisive limiting factor. This suggests that voluntary measures alone will not suffice; a coordinated framework of incentives, regulations, and stakeholder engagement is required to ensure meaningful progress.

A distinctive contribution of this study lies in its regional focus on the Banská Bystrica region of Slovakia, which has not been systematically analyzed in terms of accessible tourism until now. By combining a quantitative survey of 45 facilities with qualitative interviews analyzed through ATLAS.ti visualizations (Sankey diagrams and networks), the study offers a mixed-method approach that not only quantifies accessibility gaps but also uncovers the attitudes and reasoning of operators. This dual perspective—linking infrastructure deficits with human factors—adds depth to the existing body of literature, which often focuses exclusively either on structural barriers or on consumer perspectives. Furthermore, the study highlights the underrepresentation of intellectual and sensory disabilities in adaptation efforts, thus drawing attention to groups frequently overlooked in both research and practice. However, one limitation of this study is the absence of an explicit analysis of how Industry 4.0 applications—such as smart technologies, automation, or digital monitoring systems—might contribute to enhancing accessibility in tourism infrastructure. Although these tools hold potential for overcoming some of the spatial and organizational barriers identified, they were not within the scope of the present investigation. Their omission limits the extent to which this research can address the technological dimension of accessible tourism.

Looking forward, future research should adopt a comparative regional perspective to assess whether the barriers identified in the Banská Bystrica region are unique or shared across other Slovak regions and neighboring countries. Longitudinal studies could also examine how ongoing investments and policy interventions influence accessibility outcomes over time. Moreover, more attention should be devoted to underrepresented disability groups—particularly people with intellectual or sensory impairments—for whom current adaptations are minimal. Future work could explore also the integration of Industry 4.0 solutions, evaluating their applicability in heritage-sensitive environments and their capacity to support inclusive tourism management. Such an approach may reveal innovative pathways for balancing preservation requirements with accessibility goals. Finally, interdisciplinary approaches that integrate perspectives from tourism studies, architecture, technological solutions, social policy, and heritage conservation may yield more holistic solutions to the complex challenges of accessible tourism.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.M. and Ľ.Š.; methodology, R.M.; software, R.L.; validation, R.M. and Ľ.Š.; formal analysis, I.L.; resources, I.L. and R.L.; data curation, R.L. and R.M.; writing—original draft preparation, R.M. and Ľ.Š.; writing—review and editing, R.M. and Ľ.Š.; visualization, R.M.; supervision, R.M.; project administration, R.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no funding. It was elaborated within the framework of the project VEGA 1/0360/23 Tourism of the New generation–responsible and competitive development of tourism destinations in Slovakia in the post-COVID era.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to this research being conducted in full compliance with the Slovak Republic’s Personal Data Protection Act (https://www.slov-lex.sk/ezbierky/pravne-predpisy/SK/ZZ/2018/18/20240701, accessed on 26 September 2025). The study ensured that all participants engaged anonymously and voluntarily, having been duly informed of its purpose and the intended use of the results for academic purposes. Furthermore, no sensitive personal data, such as health-related information, biometric or genetic data, political opinions, religious beliefs, ethnic origin, or sexual orientation, was collected.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Agovino, M., Casaccia, M., Garofalo, A., & Marchesano, K. (2017). Tourism and disability in Italy: Limits and opportunities. Tourism Management Perspectives, 23, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andani, A., Rostron, J., & Sertyesilisik, B. (2013). An investigation into access issues affecting historic built environment. American Journal of Civil Engineering and Architecture, 1(2), 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, A. (2016). Social research methods (5th ed.). Oxford University Press. Available online: https://ktpu.kpi.ua/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/social-research-methods-alan-bryman.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Buhalis, D., & Darcy, S. (2010). Accessible tourism: Concepts and issues. Channel View Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Buhalis, D., Darcy, S., & Ambrose, I. (2012). Best practice in accessible tourism: Inclusion, disability, ageing population and tourism. Channel View Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, D. W., Jackson, E. L., & Godbey, G. (1991). A hierarchical model of leisure constraints. Leisure Sciences, 13(4), 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diekmann, A., McCabe, S., & Minnaert, L. (2011). Tourism today: Stakeholders, and supply and demand factors. In S. McCabe, L. Minnaert, & A. Diekmann (Eds.), Social tourism in Europe: Theory and practice (pp. 35–47). Channel View Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez, T., Fraiz, J. A., & Alén, E. (2013). Economic profitability of accessible tourism for the tourism sector in Spain. Tourism Economics, 19(6), 1385–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etikan, I., Musa, S. A., & Alkassim, R. S. (2016). Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics, 5(1), 1–4. Available online: https://sciencepublishinggroup.com/article/10.11648/j.ajtas.20160501.11 (accessed on 18 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- European Commission. (2021). Únia rovnosti: Stratégia v oblasti práv osôb so zdravotným postihnutím na roky 2021–2030. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/SK/TXT/?uri=COM:2021:101:FIN (accessed on 23 August 2023).

- Eusébio, C., Alves, J. P., Carneiro, M. J., & Teixeira, L. (2023). Needs, motivations, constraints, and benefits of people with disabilities participating in tourism activities: The view of formal caregivers. Annals of Leisure Research, 27(5), 599–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faizefu, A. R., & Neba, B. E. (2024). A historical perspective on social exclusion and physical disabilities. International Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience and Psychology, 2(1), 12–18. [Google Scholar]

- Frye, A. (2015). Capitalising on the grey-haired globetrotters: Economic aspects of increasing tourism among older and disabled people. International Transport Forum Discussion Paper. Available online: https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/121943/1/826031609.pdf (accessed on 6 November 2023).

- Fuchs, K. (2024). The barriers to accessible tourism in Phuket: Toward an exploratory framework with implications for tourism planning. Tourism: An International Interdisciplinary Journal, 71(4), 798–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gassiot, A., Prats, L., & Coromina, L. (2018). Tourism constraints for Spanish tourists with disabilities: Scale development and validation. Documents D’anàlisi Geogràfica, 64(1), 49–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillovic, B., & McIntosh, A. (2020). Accessibility and inclusive tourism development: Current state and future agenda. Sustainability, 12(22), 9722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonda, T. (2021). Travelling habits of people with disabilities. GeoJournal of Tourism and Geosites, 37(3), 844–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonda, T. (2024). The importance of infrastructure in the development of accessible tourism. Journal of Infrastructure, Policy and Development, 8(2), 2735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonda, T., Nagy, D., & Raffay, Z. (2019). The impact of tourism on the quality of life and happiness. Interdisciplinary Management Research, 15, 1790–1803. [Google Scholar]

- Gúčik, M. (2020). Cestovný ruch v ekonomike a spoločnosti. Wolters Kluwer, Bratislava. ISBN 978-8081687865. [Google Scholar]

- Haluwalia, S., Bhat, G. M., & Rani, M. (2022). Exploring the factors of social exclusion: Empirical study of rural Haryana, India. Contemporary Voice of Dalit, 14(1), 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanko, J. (Ed.). (2015). Práca s handicapovaným návštevníkom v múzeu: Zborník príspevkov zo seminára, Stará Ľubovňa, 22. júna 2015 [Work with visitors with disabilities in the museum: Proceedings from the seminar, Stará Ľubovňa, 22 June 2015]. Zväz múzeí na Slovensku, Odborná komisia pre výchovu a vzdelávanie v múzeách. ISBN 978-80-972076-4-9. [Google Scholar]

- Hefny, L. (2024). For accessible tourism experience: Exploring the blog sphere of people with disabilities. Advances in Hospitality and Tourism Research, 12(1), 33–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISTO. (2011). The social and economic benefits of social tourism. Available online: http://nationbuilder.s3.amazonaws.com/appgonsocialtourism/pages/23/attachments/original/ISTO_-_Inquiry_Social_Tourism.ISTO.pdf (accessed on 18 April 2023).

- Kastenholz, E., Eusébio, C., & Figueiredo, E. (2015). Contributions of tourism to social inclusion of persons with disability. Disability & Society, 30(8), 1259–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollarová, A., & Kollar, M. (2010). Viacnásobné postihnutie ako sociálny problém. Available online: https://www.prohuman.sk/socialna-praca/viacnasobne-postihnutie-ako-socialny-problem (accessed on 5 August 2023).

- Koustriava, E., & Koutsmani, M. (2023). Spatial and information accessibility of museums and places of historical interest: A comparison between London and Thessaloniki. Sustainability, 15(24), 16611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovačić, S., Pivac, T., Solarević, M., Blešić, I., Cimbaljević, M., Vujičić, M., Stankov, U., Besermenji, S., & Ćurčić, N. (2024). Let us hear the voice of the audience: Groups facing the risk of cultural exclusion and cultural accessibility in Vojvodina province, Serbia. Universal Access in the Information Society, 23, 1595–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruczek, Z., Gmyrek, K., Ziżka, D., Korbiel, K., & Nowak, K. (2024). Accessibility of cultural heritage sites for people with disabilities: A case study on Krakow museums. Sustainability, 16(1), 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kučera, P., & Gavurová, B. (2020). Stav bariér k mobilite a dostupnosti základných ľudských potrieb na Slovensku za rok 2019. Technická univerzita v Košiciach. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/340660782 (accessed on 16 November 2023).

- Leahy, A., & Ferri, D. (2023). Barriers to cultural participation by people with disabilities in Europe: A study across 28 countries. Disability & Society, 39(10), 2465–2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leiras, A., & Eusébio, C. (2023). Perceived image of accessible tourism destinations: A data mining analysis of Google Maps reviews. Current Issues in Tourism, 27(16), 2584–2602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linderová, I. (2015). Ekonomické a sociokultúrne dopady sociálneho cestovného ruchu. Available online: https://uni.uhk.cz/hed/site/assets/files/1048/proceedings_2015_2.pdf (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- Linderová, I. (2016, February 24–25). Přístupnost památek UNESCO pro zdravotně postižené návštevníky v České republice. 11th International Conference: Topical Issues of Tourism, Jihlava, Czech Republic. Available online: https://kcr.vspj.cz/uvod/archiv/konference/conference-topical-issues-of-tourism-2016 (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- Linderová, I., & Janeček, P. (2017). Accessible tourism for all—Current state in the Czech business and non-business environment. Ekonómie a Management, 20(4), 168–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J., Chen, Y., Kang, H., Li, C., & Meng, X. (2023). Development trends and opportunities in China’s accessible tourism market. BCP Business & Management, 50, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luiza, S. M. (2010). Accessible tourism—The ignored opportunity. Annals of the University of Oradea: Economic Science, 1(2), 1154–1157. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, S., & Proverbs, D. G. (2020). How adaptation of historic listed buildings affords access. International Journal of Building Pathology and Adaptation, 38(4), 589–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marčeková, R., Pompurová, K., Šebová, Ľ., Šimočková, I., & Liberdová, R. (2024). Is the tourism offer in the Banská Bystrica region moving towards greater inclusion? In I. Hamarneh, R. Marčeková, & Z. Kruczek (Eds.), Application of the principles of inclusion in tourism in V4 countries–theoretical definition, research, analysis, recommendations (pp. 148–158). Panevropská univerzita. Available online: https://www.peuni.cz/dokumenty/Monografie.pdf (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- Marčeková, R., & Šebová, Ľ. (2020). Ponuka cestovného ruchu pre zdravotne znevýhodnených návštevníkov na Slovensku. Vydavateľstvo Belianum, Banská Bystrica. ISBN 978-8055717852. [Google Scholar]

- Marsin, J. M., Ariffin, S. A. Y., & Shahminan, R. N. (2014). Comparison of legislation concerning people with disability and heritage environment in Malaysia and developed countries. In IOP conference series: Earth and environmental science. IOP Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrogiuseppe, M., Span, S., & Bortolotti, E. (2021). Improving accessibility to cultural heritage for people with intellectual disabilities: A tool for observing the obstacles and facilitators for the access to knowledge. European Journal of Disability Research, 15(2), 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minnaert, L., Maitland, R., & Miller, G. (2009). Tourism and social policy: The value of social tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 36(2), 316–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, S., Palmer, M., Kim, H., Mont, D., & Groce, N. (2017). Extra costs of living with a disability: A review and agenda for research. Disability and Health Journal, 10(4), 475–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura, A., Eusébio, C., & Devile, E. (2022). The ‘why’ and ‘what for’ of participation in tourism activities: Travel motivations of people with disabilities. Current Issues in Tourism, 26(6), 941–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naniopoulos, A., & Tsalis, P. (2015). A methodology for facing the accessibility of monuments developed and realised in Thessaloniki, Greece. Journal of Tourism Futures, 1(3), 240–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyanjom, J., Boxall, K., & Slaven, J. (2018). Towards inclusive tourism? Stakeholder collaboration in the development of accessible tourism. Tourism Geographies, 20(4), 675–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Önal, Ö., Güblü, M., Akyol, M. H., Kişioğlu, A. N., & Uskun, E. (2024). The impact of perceived social support and social exclusion on the quality of life of individuals with disabilities: A moderation analysis. Psychology Research on Education and Social Sciences, 5(1), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partarakis, N., Klironomos, I., Antona, M., Margetis, G., Grammenos, D., & Stephanidis, C. (2016). Accessibility of cultural heritage exhibits. In M. Antona, & M. Antona (Eds.), Universal access in human-computer interaction. Interaction techniques and environments (pp. 444–455). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perangin-Angin, R., Tavakoli, R., & Kusumo, C. (2023). Inclusive tourism: The experience and expectations of Indonesian wheelchair tourists in nature tourism. Tourism Recreation Research, 48(6), 955–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plimmer, F., Pottinger, G., & Goodall, B. (2006). Accessibility issues for heritage properties: A frame of mind? Shaping the Change. XXIII FIG Congress. Available online: https://www.fig.net/resources/proceedings/fig_proceedings/fig2006/papers/ps08/ps08_05_plimmer_etal_0269.pdf (accessed on 21 January 2023).

- Reyes-García, M. E., Criado-García, F., Camúñez-Ruíz, J. A., & Casado-Pérez, M. (2021). Accessibility to cultural tourism: The case of the major museums in the city of Seville. Sustainability, 13(6), 3432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Escuderos, L., García-Andreau, H., Michopoulou, E., & Buhalis, D. (2021). Perspectives on experiences of tourists with disabilities: Implications for their daily lives and for the tourist industry. Tourism Recreation Research, 49(1), 48–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana-Santana, S. B., Peña-Alonso, C., & Espino, E. P. (2020). Assessing physical accessibility conditions to tourist attractions: The case of Maspalomas Costa Canaria urban area (Gran Canaria, Spain). Applied Geography, 125, 102327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, R., & Parween, S. (2021). Disability and exclusion: Social, education and employment perspectives. Bhutan Journal of Research and Development, 10(2), 29–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stankova, M., Amoiradis, C., Velissariou, E., & Grigoriadou, D. (2021). Accessible tourism in Greece: A satisfaction survey on tourists with disabilities. Management Research and Practice, 13(1), 5–15. Available online: http://mrp.ase.ro/no131/f1.pdf (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Statistical Office of the Slovak Republic. (2024). Tourism in the banská bystrica region—accommodation and visitor statistics. Available online: https://datacube.statistics.sk/#!/view/sk/VBD_SK_WIN2/cr3808qr/v_cr3808qr_00_00_00_sk (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- UNDP. (2016). Human development report 2016: Human development for everyone. Available online: https://hdr.undp.org/content/human-development-report-2016 (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- UNWTO. (2013). Recommendations on accessible tourism for all. Available online: https://www.accessibletourism.org/resources/accesibilityen_2013_unwto.pdf (accessed on 6 January 2023).

- UNWTO. (2018). Global report on inclusive tourism destinations: Model and success stories. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/middle-east/publication/global-report-inclusive-tourism-destinations-model-and-success-stories (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- UNWTO. (2023). Recommendations for key players in the cultural tourism ecosystem. Available online: https://webunwto.s3.eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/2023-09/Cultura-ING_ACC.pdf?VersionId=JUTDNhf8hNBZdgAeBayWzv.ZOqlD.Eta (accessed on 15 February 2024).

- Warren, A., Chege, W., Greene, M., & Berdie, L. (2023). The financial health of people with disabilities: Key obstacles and opportunities. Available online: https://finhealthnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/The-Financial-Health-of-People-With-Disabilities_Key-Obstacles-and-Opportunities.pdf (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- Załuska, U., Kwiatkowska-Ciotucha, D., & Greśkowiak, A. (2022). Travelling from perspective of persons with disability: Results of an international survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(17), 10575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Závodi, B., Szabó, G., & Alpek, L. B. (2021). Survey of the consumer attitude of tourists visiting South Transdanubia, Hungary. GeoJournal of Tourism and Geosites, 34(1), 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenko, Z., & Sardi, V. (2014). Systematic thinking for socially responsible innovations in social tourism for people with disabilities. Kybernetes, 43(3/4), 652–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).