Visual eWOM and Brand Factors in Shaping Hotel Booking Decisions: A UK Hospitality Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials

2.1. Literature Review

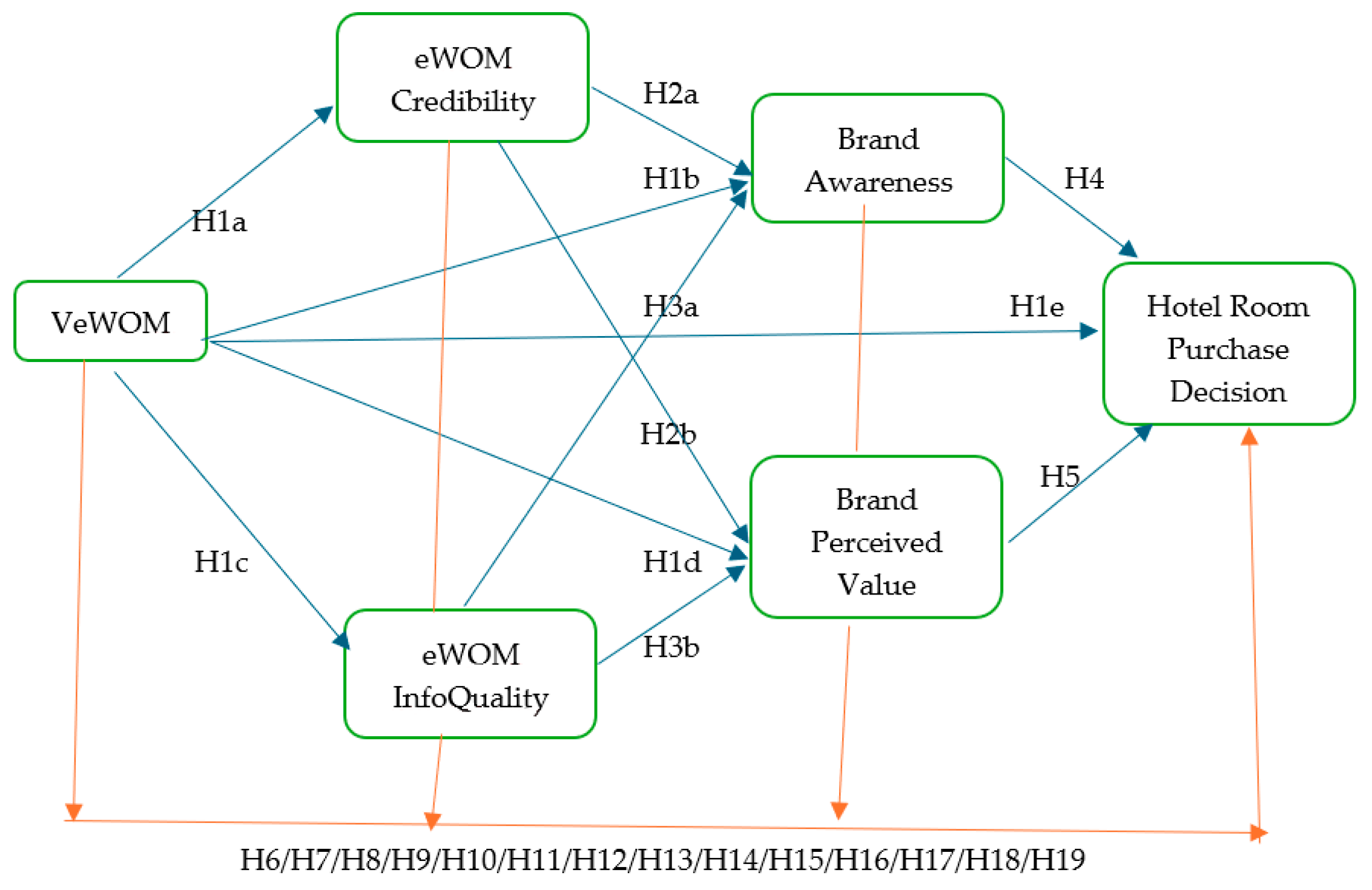

2.2. Research Conceptualization

2.3. Theoretical Framework and Hypothesis Development

2.4. Mediation

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Research Design and Procedures

3.2. Measurement Scales

3.3. Data Collection

- (i)

- Demographic Information

- (ii)

- Sampling Method

4. Data Analysis

4.1. Assessment of the Measurement Model

- Brand Awareness (BA): √AVE = 0.889, which is higher than the correlation with VeWOM 0.357 → Valid.

- Brand Value (BV): √AVE = 0.828, which is higher than the correlation with VeWOM 0.411) → Valid.

- Purchase Decision (PD): √AVE = 0.922 which is higher than the correlation with VeWOM 0.576) → Valid.

- eWOM Information Quality (InfoQuality): √AVE = 0.814, which is higher than the correlation with VeWOM 0.424) → Valid.

- eWOM Credibility (Credibility): √AVE = 0.877, which is higher than the correlation with VeWOM 0.857) → Valid.

4.2. Assessment of the Structural Model

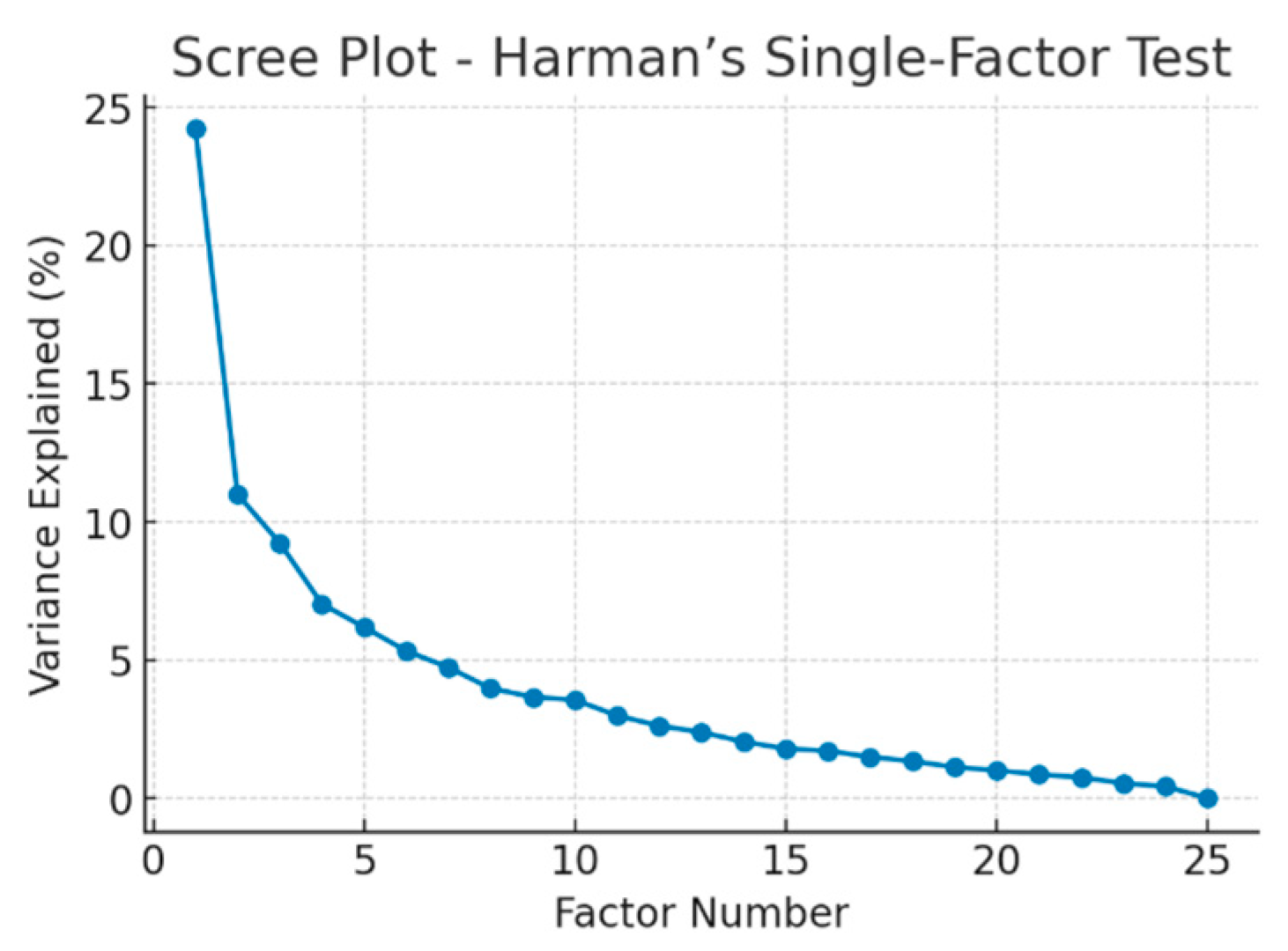

4.2.1. Common Method Bias Assessment

4.2.2. Sequential Mediation Analysis Results (Table 9)

- ⮚

- Result shows that H6 is supported (Table 4). There is a significant mediation effect of eWOM Credibility on VeWOM and BA as t-value = 2.210; p-value = 0.027; = − 0.034.

- ⮚

- H7 is not supported. There are no significant mediation effects of BA on VeWOM and PD as t-value = 0.075; p-value = 0.940; = 0.001.

- ⮚

- H8 is supported. eWOM InfoQuality has a significant mediation effect on VeWOM and BV and t-value = 2.221; p-value = 0.026; = 0.043 (H8).

- ⮚

- H9 is not supported. “t-value = 2.262; p-value = 0.024; = −0.039”, thus “BA does not have a mediation effect on eWOM Credibility and PD”.

- ⮚

- H10 is supported, with “t-value = 4.475; p-value = 0.000; = 0.126”, and eWOM InfoQuality is positively and significantly mediating on VeWOM and BA.

- ⮚

- H11 is supported, where BV has a positive significant mediation with eWOM Credibility and PD. T-value = 2.117; p-value = 0.034; = 0.047. There is a strong mediation when higher eWOM Credibility enhances Brand Value, leading to stronger Purchase Decisions.

- ⮚

- H12 is supported, as t-value = 3.312; p-value = 0.001; = 0.063; BV has significant mediation with VeWOM and PD. It shows that Visual eWOM directly strengthens Brand Value, which increases the likelihood of purchase.

- ⮚

- H13 is supported with t-value = 2.132; p-value = 0.033; = 0.053; BV has significant mediation with eWOM InfoQuality and PD.

- ⮚

- H14 is supported too, with t-value = 3.747; p-value = 0.000; = 0.110; BA has a significant mediation and is positively related to eWOM InfoQuality and PD (H14) and t-value = 2.923.

- ⮚

- Results show that eWOM Credibility does not have significant mediation with VeWOM and BV, t-value = 1.795; p-value = 0.073; = 0.028. H15 is not supported.

- ⮚

- H16 is supported. p-value = 0.003; = 0.030; eWOM InfoQuality and BA have significant mediation with VeWOM and PD.

- ⮚

- Results also indicate that there are no significant mediations between constructs for H17—not supported. t-value = 1.904; p-value = 0.057; = −0.008. eWOM Credibility and BA do not have significant mediation with VeWOM and PD; t-value = 1.774; p-value = 0.076; = 0.009.The mediation path H17, where Visual eWOM → eWOM Credibility → Brand Awareness → Purchase Decision, since the CI does not include zero. This suggests a statistically not significant mediation effect, meaning Visual eWOM does not influence Purchase Decision via eWOM Credibility and Brand Awareness.

- ⮚

- eWOM Credibility and BV do not significantly mediate with VeWOM and PD (H18), and so as for H19 where t-value = 1.927; p-value = 0.054; = 0.014, the following is true.

- ⮚

- H19 is not supported, and eWOM InfoQuality and BV do not have significant mediation with VeWOM and PD. H19. Visual eWOM → eWOM Info Quality → Brand Value → Purchase Decision with Indirect Effect: 0.0114. There was no significant mediation where eWOM InfoQuality does not influence Brand Value and Purchase Decision (Table 9).

- ⮚

- Thus, it can be summarized that Brand Value is a critical mediator in driving Purchase Decisions. eWOM Credibility and Info Quality significantly impact Brand Value, reinforcing the importance of credible and high-quality online reviews. Visual eWOM has both direct and indirect effects on purchase behavior when BV resonates the relationships between constructs.

| Supported? | “Beta” | “Standard Deviation (STDEV)” | “T Statistics” | “p Values” | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H6. Visual eWOM -> eWOM Credibility -> Brand Awareness | Yes | −0.034 | 0.015 | 2.210 | 0.027 |

| H7. Visual eWOM -> Brand Awareness -> Purchase Decision | No | 0.001 | 0.012 | 0.075 | 0.940 |

| H8. Visual eWOM -> eWOM InfoQuality -> Brand Value | Yes | 0.043 | 0.019 | 2.221 | 0.026 |

| H9. eWOM Credibility -> Brand Awareness -> Purchase Decision | No | −0.039 | 0.017 | 2.262 | 0.024 |

| H10. Visual eWOM -> eWOM InfoQuality -> Brand Awareness | Yes | 0.126 | 0.028 | 4.475 | 0.000 |

| H11. eWOM Credibility -> Brand Value -> Purchase Decision | Yes | 0.047 | 0.022 | 2.117 | 0.034 |

| H12. Visual eWOM -> Brand Value -> Purchase Decision | Yes | 0.063 | 0.019 | 3.312 | 0.001 |

| H13. eWOM InfoQuality -> Brand Value -> Purchase Decision | Yes | 0.053 | 0.025 | 2.132 | 0.033 |

| H14. eWOM InfoQuality -> Brand Awareness -> Purchase Decision | Yes | 0.110 | 0.029 | 3.747 | 0.000 |

| H15. Visual eWOM -> eWOM Credibility -> Brand Value | No | 0.028 | 0.016 | 1.795 | 0.073 |

| H16. Visual eWOM -> eWOM InfoQuality -> Brand Awareness -> Purchase Decision | Yes | 0.030 | 0.010 | 2.923 | 0.003 |

| H17. Visual eWOM -> eWOM Credibility -> Brand Awareness -> Purchase Decision | No | −0.008 | 0.004 | 1.904 | 0.057 |

| H18. Visual eWOM -> eWOM Credibility -> Brand Value -> Purchase Decision | No | 0.009 | 0.005 | 1.774 | 0.076 |

| H19. Visual eWOM -> eWOM InfoQuality -> Brand Value -> Purchase Decision | No | 0.014 | 0.007 | 1.927 | 0.054 |

5. Discussion and Implications

5.1. Theoretical Implication

5.2. Managerial Implications

6. Conclusions

7. Limitations and Future Studies

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aaker, D. A. (1996). Building strong brands. Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- An, Q., Ma, Y., Du, Q., Xiang, Z., & Fan, W. (2020). Role of user-generated photos in online hotel reviews: An analytical approach. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 45, 633–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babić Rosario, A., de Valck, K., & Sotgiu, F. (2020). Conceptualizing the electronic word-of-mouth process: What we know and need to know about eWOM creation, exposure, and evaluation. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 48(3), 422–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S., & Chua, A. Y. K. (2019). Trust in online hotel reviews across review polarity and hotel category. Computers in Human Behavior, 90(December 2017), 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, B. M., & Reith, R. (2022). Cultural differences in the perception of credible online reviews—The influence of presentation format. Decision Support Systems, 154, 113710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, C. T., Ngo, T. T. A., Chau, H. K. L., & Tran, N. P. N. (2025). How perceived eWOM in visual form influences online purchase intention on social media: A research based on the SOR theory. PLoS ONE, 20(7), e0328093. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12244485/ (accessed on 8 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Bushara, M. A., Abdou, A. H., Hassan, T. H., Sobaih, A. E. E., Albohnayh, A. S. M., Alshammari, W. G., Aldoreeb, M., Elsaed, A. A., & Elsaied, M. A. (2023). Power of Social Media Marketing: How Perceived Value Mediates The Impact On Restaurant Followers’ Purchase Intention, Willingness To Pay A Premium Price, and E-WOM? Sustainability, 15(6), 5331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, U. (2019). The impact of source credible online reviews on purchase intention: The mediating roles of brand equity dimensions. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 13(2), 142–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, U., & Bhat, S. (2018). The effect of credible online reviews on brand equity dimensions and its consequences on consumer behavior. Journal of Promotion Management, 24(1), 57–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W. W. (1998). Commentary: Issues and opinion on structural equation modeling (Vol. 22, pp. 1–14). MIS Quarterly. [Google Scholar]

- Dabbous, A., & Barakat, K. A. (2020). Bridging the online offline gap: Assessing the impact of brands’ social network content quality on brand awareness and purchase intention. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 53, 101966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W., Yi, M., & Lu, Y. (2020). Vote or not? How various information cues affect helpfulness voting of online reviews. Online Information Review, 44(4), 787–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diwanji, V. S., & Cortese, J. (2020). Contrasting user generated videos versus brand generated videos in ecommerce. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 54, 102024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Baz, B. E.-S., Elseidi, B. I., & El-Maniaway, A. M. (2018). Influence of Electronic Word-of-Mouth (e-WOM) on Brand Credibility and Egyptian Consumers’ Purchase Intentions. International Journal of Online Marketing, 8(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filieri, R. (2015). What makes online reviews helpful ? A diagnosticity-adoption framework to explain informational and normative in fl uences in e-WOM. Journal of Business Research, 68(6), 1261–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filieri, R. (2016). Annals of tourism research what makes an online consumer review trustworthy ? Annals of Tourism Research, 58, 46–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filieri, R., Galati, F., & Raguseo, E. (2021a). The impact of service attributes and category on eWOM helpfulness: An investigation of extremely negative and positive ratings using latent semantic analytics and regression analysis. Computers in Human Behavior, 114, 106527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filieri, R., Hofacker, C. F., & Alguezaui, S. (2018a). What makes information in online consumer reviews diagnostic over time? The role of review relevancy, factuality, currency, source credibility and ranking score. Computers in Human Behavior, 80, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filieri, R., Lin, Z., Pino, G., Alguezaui, S., & Inversini, A. (2021b). The role of visual cues in eWOM on consumers’ behavioral intention and decisions. Journal of Business Research, 135, 663–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filieri, R., & McLeay, F. (2014). E-WOM and accommodation: An analysis of the factors that influence travelers’ adoption of information from online reviews. Journal of Travel Research, 53(1), 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filieri, R., McLeay, F., Tsui, B., & Lin, Z. (2018b). Consumer perceptions of information helpfulness and determinants of purchase intention in online consumer reviews of services. Information and Management, 55(8), 956–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filieri, R., Raguseo, E., & Vitari, C. (2018c). When are extreme ratings more helpful? Empirical evidence on the moderating effects of review characteristics and product type. Computers in Human Behavior, 88, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filieri, R., Vitari, C., & Raguseo, E. (2020). Extreme negative rating and review helpfulness: The moderating role of product quality. Journal of Travel Research, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-de-Blanes-Sebastián, M., Corral-de-la-Mata, D., Azuara-Grande, A., & Sarmiento-Guede, J. R. (2024a). The model of electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) information acceptance in hotel booking. Profesional de la información, 33(2), e330206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-de-Blanes-Sebastián, M., López-Bonilla, J. M., & López-Bonilla, L. M. (2024b). Visual eWOM and consumer trust in post-COVID hotel selection: The mediating role of brand credibility. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 30(1), 42–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graciola, A. P., De Toni, D., Milan, G. S., & Eberle, L. (2020). Mediated-moderated effects: High and low store image, brand awareness, perceived value from mini and supermarkets retail stores. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 55, 102117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Howard, M. C., & Nitzl, C. (2020). Assessing measurement model quality in PLS-SEM using confirmatory composite analysis. Journal of Business Research, 109(November 2019), 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2013). Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling: Rigorous Applications, Better Results and Higher Acceptance. Long Range Planning, 46(1–2), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heider, F. (1958). The psychology of interpersonal relations. Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Ortega, B. (2020). When the performance comes into play: The influence of positive online consumer reviews on individuals’ post-consumption responses. Journal of Business Research, 113, 422–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, F., Teichert, T., Deng, S., Liu, Y., & Zhou, G. (2021). Dealing with pandemics: An investigation of the effects of COVID-19 on customers’ evaluations of hospitality services. Tourism Management, 85, 104320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, Y., & Jang, S. C. (2023). The Effect of COVID-19 on hotel booking intentions: Investigating the roles of message appeal type and brand loyalty. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 108, 103357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K. L. (1993). Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. Journal of Marketing, 57(1), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, H. H., & Michela, J. L. (1980). Attribution theory and research. Annual Review of Psychology, 31, 457–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. J., & Han, H. (2022). Saving the hotel industry: Strategic response to the COVID-19 pandemic, hotel selection analysis, and customer retention. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 102, 103163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M., Lee, S. M., Choi, S., & Kim, S. Y. (2021). Impact of visual information on online consumer review behavior: Evidence from a hotel booking website. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 60, 102494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. (2015). Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. International Journal of e-Collaboration, 11(4), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, K. P., Chong, S. C., & Lin, B. (2023). How older adults’ health beliefs affect intention to perform COVID-19 self-examination: A reasoned action approach. Human Systems Management, 42(5), 569–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, K. P., Chong, S. C., & Lin, B. (2025a). A mean-end-chain (MEC) lens of quality of care on customer equity, recommendations and revisit intention. International Journal of Quality and Service Sciences, 17(1), 105–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, K. P., Chong, S. C., & Lin, B. (2025b). Linking post-COVID-19 distress with health beliefs and online food purchasing behavioral intentions: A Malaysian context. Journal of International Food & Agribusiness Marketing, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M., & Youn, S. (2009). Electronic word of mouth (eWOM): How eWOM platforms influence consumer product judgement. International Journal of Advertising, 28(3), 473–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K., Du, W., Yang, S., Liu, C., & Na, S. (2023). The effects of social media communication and e-WOM on brand equity: The moderating roles of product involvement. Sustainability, 15(8), 6424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S., Gao, G., Gallivan, M., & Gong, J. (2020). Online review helpfulness: Impact of reviewer disclosure and consumer goals. Decision Support Systems, 129, 113183. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X. X., Zhang, Z. Q., Law, R., & Zhang, Z. L. (2024). Words meet photos: How visual content impact rating. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 123, 103945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, A. S., & Yao, S. S. (2019). What makes hotel online reviews credible?: An investigation of the roles of reviewer expertise, review rating consistency and review valence. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 31(1), 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, J., Shan, W., Wang, Y., & Xiao, J. (2019). Computers in human behavior how easy-to-process information in fluences consumers over time: Online review vs. brand popularity. Computers in Human Behavior, 97, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, A., Baker, A., & Donthu, N. (2019). Capturing dynamics in the value for brand recommendations from word-of-mouth conversations. Journal of Business Research, 104, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C., Hasan, N. A. M., Zamri bin Ahmad, A. M., & Lei, G. (2025). Influence of short video content on consumers’ purchase intentions on social media platforms with trust as a mediator. Scientific Reports, 15(1), 16605. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12075488/ (accessed on 8 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Mackiewicz, J., & Yeats, D. (2014). Product review users’ perceptions of review quality: The role of credibility, informativeness, and readability. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 57(4), 309–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinko, M. J., & Mackey, J. D. (2019). Attribution theory: An introduction to the special issue. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 40(5), 523–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massidda, C., Piras, R., & Seetaram, N. (2020). A microeconomics analysis of the per diem expenditure of british travellers. Annals of Tourism Research, 82, 102877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizerski, R. W., Golden, L. L., & Kernan, J. B. (1979). The attribution process in consumer decision making. Journal of Consumer Research, 6(2), 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Science Council Malaysia. (2021). Malaysian code of responsible conduct in research (2nd ed.). Academy of Sciences Malaysia (ASM). ISBN 978-983-2915-54-3. Available online: https://rmc.uitm.edu.my/images/Download/Guidelines/MOSTI/MCRCR_Edition2_19032021.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- Olesen, A. P., Amin, L., & Mahadi, Z. (2019). Research ethics: Researchers consider how best to prevent misconduct in research in Malaysian higher learning institutions through ethics education. Science and Engineering Ethics, 25, 1111–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pooja, K., & Upadhyaya, P. (2022). What makes an online review credible? A systematic review of the literature and future research directions. Management Review Quarterly, 74(2), 627–659. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11301-022-00312-6 (accessed on 14 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L., Pang, J., & Lim, K. H. (2012). Effects of conflicting aggregated rating on eWOM review credibility and diagnosticity: The moderating role of review valence. Decision Support Systems, 54(1), 631–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rifon, N. J., Choi, S. M., Trimble, C. S., & Li, H. (2004). Congruence effects in sponsorship: The mediating role of sponsor credibility and consumer attributions of sponsor motive. Journal of Advertising, 33(1), 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosli, N., Che Ha, N., & Ghazali, E. M. (2019). Bridging the gap between branding and sustainability by fostering brand credibility and brand attachment in travellers’ hotel choice. Bottom Line, 32(4), 308–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S., & Lerman, D. (2007). Why are you telling me this? An examination into negative consumer reviews on the web. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 21(3), 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, A., & Mishra, A. (2023). Role of Review Length, Review Valence and Review Credibility on Consumer’s Online Hotel Booking Intention. FIIB Business Review, 12(4), 403–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y., Liu, K., Guo, L., Yang, Z., & Jin, M. (2022). Does hotel customer satisfaction change during the COVID-19 ? A perspective from online reviews. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 51, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanaki, M. Z., Papatheodorou, A., & Pappas, N. (2021). Tourism in the post COVID-19 era: Evidence from hotels in the North East of England. Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes, 13(3), 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sürücü, Ö., Öztürk, Y., Okumus, F., & Bilgihan, A. (2019). Brand awareness, image, physical quality and employee behavior as building blocks of customer-based brand equity: Consequences in the hotel context. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 40(November 2018), 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taherdoost, H. (2019). What is the best response scale for survey and questionnaire design; Review of different lengths of rating scale/attitude scale/likert scale. International Journal of Academic Research in Management (IJARM), 8(1), 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Touni, R., Kim, W. G., Haldorai, K., & Rady, A. (2022). Customer engagement and hotel booking intention: The mediating and moderating roles of customer-perceived value and brand reputation. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 104(April), 103246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veloso, B. M., Leal, F., Malheiro, B., & Burguillo, J. C. (2019). On-line guest profiling and hotel recommendation. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 34, 100832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, D., Dewani, P. P., Behl, A., Pereira, V., Dwivedi, Y. K., & Del Giudice, M. (2023). A meta-analysis of antecedents and consequences of eWOM credibility: Investigation of moderating role of culture and platform type. Journal of Business Research, 154, 113292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeulen, I. E., & Seegers, D. (2009). Tried and tested: The impact of online hotel reviews on consumer consideration. Tourism Management, 30(1), 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Kim, J., & Kim, J. (2021). The financial impact of online customer reviews in the restaurant industry: A moderating effect of brand equity. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 95, 102895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., & Li, C. (2022). Differences between the formation of tourism purchase intention and the formation of actual behavior: A meta-analytic review. Tourism Management, 91, 104527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, B. (2008). Reflections on the history of attribution theory and research: People, personalities, publications, problems. Social Psychology, 39(3), 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, G., Cao, X., Lin, X., & Xiao, S. H. (2020). When online reviews meet virtual reality: Effects on consumer hotel booking. Annals of Tourism Research, 81, 102860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Xiong, Y., & Lee, T. J. (2020). A culture-oriented model of consumers’ hedonic experiences in luxury hotels. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 45, 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D., Luo, Q., & Ritchie, B. W. (2021). Afraid to travel after COVID-19? Self-protection, coping and resilience against pandemic ‘travel fear’. Tourism Management, 83, 104261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L., Li, H., He, W., & Hong, C. (2020). What influences online reviews’ perceived information quality?: Perspectives on information richness, emotional polarity and product type. Electronic Library, 38(2), 273–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| • H6: “The effect of Visual eWOM on Brand Awareness is mediated by eWOM Credibility”. |

| • H7: “The effect of Visual eWOM on Purchase Decision is mediated by Brand Awareness”. |

| • H8: “The effect of Visual eWOM on Brand Value is mediated by eWOM InfoQuality”. |

| • H9: “The effect of eWOM Credibility on Purchase Decision is mediated by Brand Awareness”. |

| • H10: “The effect of Visual eWOM on Brand Awareness is mediated by eWOM InfoQuality”. |

| • H11: “The effect of eWOM Credibility on Purchase Decision is mediated by Brand Value” |

| • H12: “The effect of Visual eWOM on Purchase Decision is mediated by Brand Value”. |

| • H13: “The effect of eWOM InfoQuality on Purchase Decision is mediated by Brand Value”. |

| • H14: “The effect of eWOM InfoQuality on Purchase Decision is mediated by Brand Awareness”. |

| • H15: “The effect of Visual eWOM on Brand Value is mediated by eWOM Credibility”. |

| • H16: “The effect of Visual eWOM on Purchase Decision is mediated by eWOM InfoQuality and Brand Awareness”. |

| • H17: “The effect of Visual eWOM on Purchase Decision is mediated by eWOM Credibility and Brand Awareness”. |

| • H18: “The effect of Visual eWOM on Purchase Decision is mediated by eWOM Credibility and Brand Value”. |

| • H19: “The effect of Visual eWOM on Purchase Decision is mediated by eWOM InfoQuality and Brand Value”. |

| Item ID | Loadings | Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability | AVE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brand Awareness | BA_1 | 0.927 | 0.911 | 0.938 | 0.790 |

| BA_2 | 0.916 | ||||

| BA_3 | 0.883 | ||||

| BA_4 | 0.824 | ||||

| Brand Value | BV_1 | 0.788 | 0.784 | 0.867 | 0.685 |

| BV_2 | 0.803 | ||||

| BV_3 | 0.888 | ||||

| Purchase Decision | PD_1 | 0.765 | 0.912 | 0.945 | 0.850 |

| PD_3 | 0.906 | ||||

| PD_4 | 0.695 | ||||

| eWOM Information Quality | InfoQuality_1 | 0.834 | 0.828 | 0.886 | 0.662 |

| InfoQuality_2 | 0.890 | ||||

| InfoQuality_3 | 0.719 | ||||

| InfoQuality_6 | 0.803 | ||||

| eWOM Credibility | Credibility_1 | 0.888 | 0.900 | 0.930 | 0.769 |

| Credibility_2 | 0.853 | ||||

| Credibility_3 | 0.912 | ||||

| Credibility_4 | 0.854 | ||||

| Visual eWOM | VeWOM_1 | 0.807 | 0.906 | 0.931 | 0.729 |

| VeWOM_2 | 0.912 | ||||

| VeWOM_3 | 0.905 | ||||

| VeWOM_4 | 0.751 | ||||

| VeWOM_5 | 0.882 |

| Visual eWOM_ | eWOM Credibility | eWOM InfoQuality | Brand Awareness | Brand Value | Purchase Decision | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| “VeWOM_1” | 0.807 | 0.201 | 0.219 | 0.07 | 0.202 | 0.106 |

| “VeWOM_2” | 0.912 | 0.213 | 0.314 | 0.072 | 0.334 | 0.151 |

| “VeWOM_3” | 0.905 | 0.174 | 0.357 | 0.071 | 0.328 | 0.213 |

| “VeWOM_4” | 0.751 | 0.133 | 0.191 | 0.057 | 0.202 | 0.052 |

| “VeWOM_5” | 0.882 | 0.21 | 0.303 | 0.041 | 0.325 | 0.143 |

| “Credibility_1” | 0.258 | 0.888 | 0.760 | 0.145 | 0.305 | 0.379 |

| “Credibility_2” | 0.187 | 0.853 | 0.654 | 0.236 | 0.271 | 0.284 |

| “Credibility_3” | 0.247 | 0.912 | 0.700 | 0.138 | 0.301 | 0.352 |

| “Credibility_4” | 0.236 | 0.854 | 0.746 | 0.189 | 0.331 | 0.431 |

| “InfoQuality_1” | 0.313 | 0.674 | 0.834 | 0.341 | 0.274 | 0.506 |

| “InfoQuality_2” | 0.352 | 0.657 | 0.890 | 0.292 | 0.301 | 0.424 |

| “InfoQuality_3” | 0.263 | 0.619 | 0.719 | 0.247 | 0.264 | 0.212 |

| “InfoQuality_6” | 0.322 | 0.585 | 0.803 | 0.172 | 0.378 | 0.537 |

| “BA_1” | 0.037 | 0.146 | 0.301 | 0.927 | −0.186 | 0.121 |

| “BA_2” | 0.057 | 0.166 | 0.285 | 0.916 | −0.136 | 0.203 |

| “BA_3” | 0.107 | 0.245 | 0.370 | 0.883 | −0.049 | 0.197 |

| “BA_4” | 0.108 | 0.159 | 0.262 | 0.824 | −0.062 | 0.179 |

| “BV_1” | 0.335 | 0.306 | 0.280 | −0.019 | 0.788 | 0.297 |

| “BV_2” | 0.313 | 0.211 | 0.213 | −0.165 | 0.803 | 0.169 |

| “BV_3” | 0.343 | 0.307 | 0.417 | −0.118 | 0.888 | 0.427 |

| “PD_1” | 0.133 | 0.336 | 0.495 | 0.226 | 0.078 | 0.765 |

| “PD_3” | 0.227 | 0.409 | 0.535 | 0.191 | 0.506 | 0.906 |

| “PD_4” | 0.042 | 0.318 | 0.350 | 0.015 | 0.094 | 0.695 |

| Brand Awareness | Brand Value | Credibility | InfoQuality | Purchase Decision | Visual eWOM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brand Awareness | ||||||

| Brand Value | 0.118 | |||||

| Credibility | 0.190 | 0.334 | ||||

| InfoQuality | 0.394 | 0.357 | 0.840 | |||

| Purchase Decision | 0.221 | 0.310 | 0.484 | 0.656 | ||

| Visual eWOM | 0.112 | 0.301 | 0.223 | 0.308 | 0.177 |

| BA | BV | PD | InfoQuality | Credibility | VeWOM | Discriminant Validity Met/Square Root of AVE > LVC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brand Awareness (BA) | 0.889 | Yes | |||||

| Brand Value (BV) | 0.122 | 0.828 | Yes | ||||

| Purchase Decision (PD) | 0.205 | 0.41 | 0.922 | Yes | |||

| eWOM Information Quality (InfoQuality) | 0.091 | 0.426 | 0.21 | 0.814 | Yes | ||

| eWOM Credibility (Credibility) | 0.212 | 0.362 | 0.435 | 0.278 | 0.877 | Yes | |

| Visual eWOM (VeWOM) | 0.357 | 0.411 | 0.576 | 0.424 | 0.857 | 0.854 | Yes |

| VIF | |

|---|---|

| Brand Awareness | 1.019 |

| Brand Value | 1.081 |

| eWOM Credibility | 2.110 |

| eWOM InfoQuality | 2.183 |

| Visual eWOM | 1.078 |

| Endogeneous Latent Construct | R Square (R2) | Q Square (Q2) |

|---|---|---|

| eWOM Credibility | 0.040 | 0.030 |

| eWOM InfoQuality | 0.073 | 0.046 |

| Brand Awareness | 0.135 | 0.103 |

| BrandValue | 0.138 | 0.084 |

| Purchase Decision | 0.167 | 0.073 |

| Hypotheses | Support? | Standard Beta | Standard Error | T Statistics | p Values | Confidence Interval | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.50% | 97.50% | |||||||

| H1a | Visual eWOM -> eWOM Credibility | Yes | 0.201 | 0.050 | 4.006 *** | 0.000 | 0.106 | 0.300 |

| H1b | Visual eWOM -> eWOM InfoQuality | Yes | 0.269 | 0.043 | 6.207 *** | 0.000 | 0.184 | 0.355 |

| H1c | Visual eWOM -> Brand Awareness | No | 0.004 | 0.052 | 0.076 ns | 0.940 | −0.095 | 0.107 |

| H1d | Visual eWOM -> BrandValue | Yes | 0.188 | 0.049 | 3.802 *** | 0.000 | 0.092 | 0.284 |

| H1e | Visual eWOM -> Purchase Decision | No | 0.038 | 0.055 | 0.689 ns | 0.491 | −0.066 | 0.150 |

| H2a | eWOM Credibility -> Brand Awareness | No (negative) | −0.167 | 0.063 | 2.650 ns | 0.008 | −0.290 | −0.043 |

| H2b | eWOM Credibility -> BrandValue | Yes | 0.140 | 0.065 | 2.152 ** | 0.031 | 0.019 | 0.272 |

| H3a | eWOM InfoQuality -> Brand Awareness | Yes | 0.469 | 0.063 | 7.443 *** | 0.000 | 0.347 | 0.598 |

| H3b | eWOM InfoQuality -> BrandValue | Yes | 0.158 | 0.064 | 2.478 ** | 0.013 | 0.025 | 0.279 |

| H4 | Brand Awareness -> Purchase Decision | Yes | 0.236 | 0.042 | 5.628 *** | 0.000 | 0.150 | 0.316 |

| H5 | BrandValue -> Purchase Decision | Yes | 0.335 | 0.049 | 6.796 *** | 0.000 | 0.236 | 0.430 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chu, W.; Lai, K.P.; Nathan, R.J. Visual eWOM and Brand Factors in Shaping Hotel Booking Decisions: A UK Hospitality Study. Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6040171

Chu W, Lai KP, Nathan RJ. Visual eWOM and Brand Factors in Shaping Hotel Booking Decisions: A UK Hospitality Study. Tourism and Hospitality. 2025; 6(4):171. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6040171

Chicago/Turabian StyleChu, WinnieSiewKoon, Kim Piew Lai, and Robert Jeyakumar Nathan. 2025. "Visual eWOM and Brand Factors in Shaping Hotel Booking Decisions: A UK Hospitality Study" Tourism and Hospitality 6, no. 4: 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6040171

APA StyleChu, W., Lai, K. P., & Nathan, R. J. (2025). Visual eWOM and Brand Factors in Shaping Hotel Booking Decisions: A UK Hospitality Study. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(4), 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6040171