Criteria for the Design of Mobile Applications to Cultural Heritage Tourism: The Case of Riobamba

Abstract

1. Introduction

Cultural Tourism Diagnosis: The Case of Riobamba

2. Materials and Methods

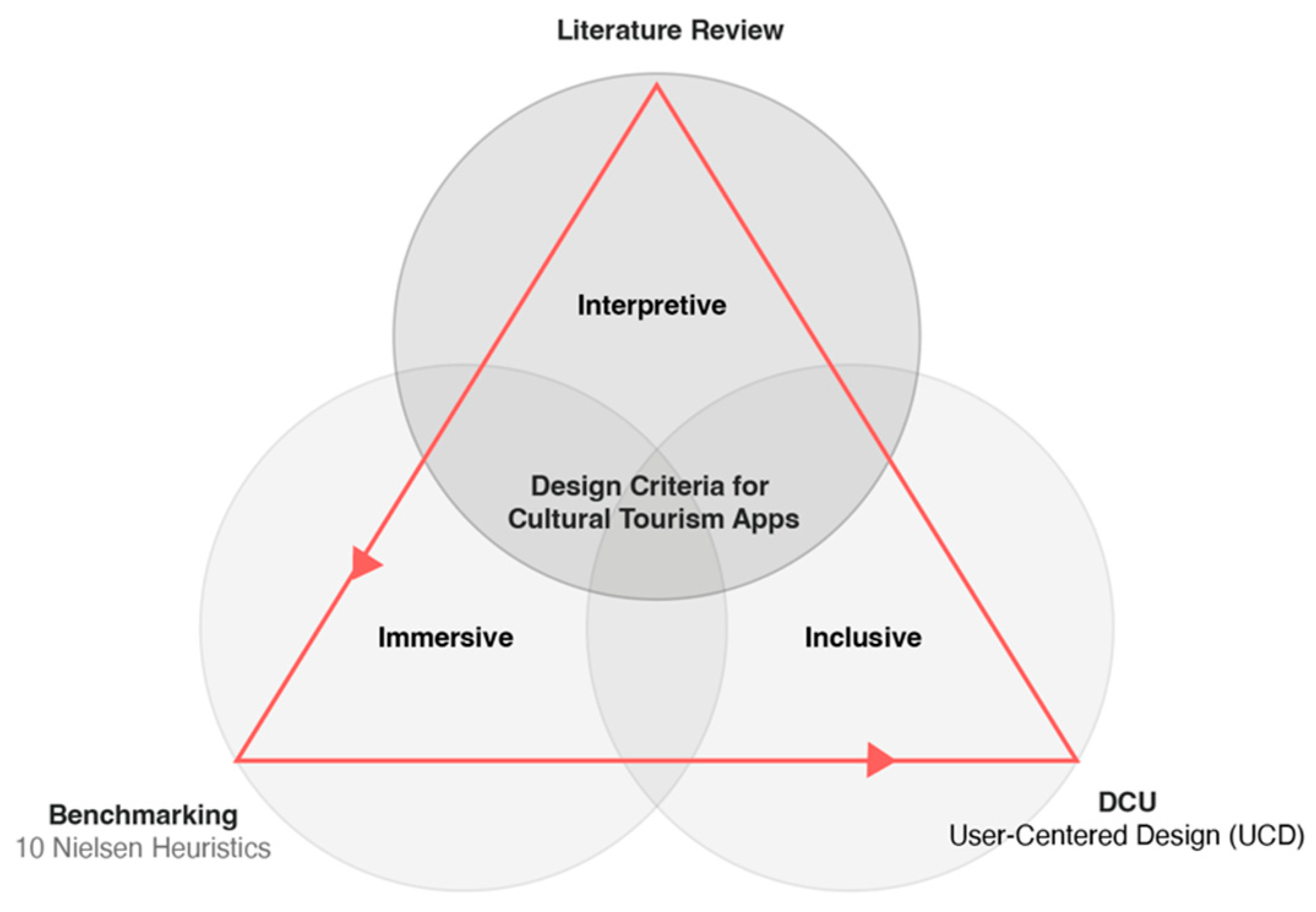

- The interpretive dimension focuses on providing content that not only informs, but also helps visitors understand and appreciate the heritage they engage with.

- The inclusive dimension ensures that such applications are accessible to all visitor profiles, reducing barriers and promoting equitable participation.

- The immersive dimension seeks to create an engaging experience that encourages exploration, active participation, and emotional connection with heritage.

3. Results

3.1. Literature Review

3.1.1. Profile of the Cultural Heritage Tourist

3.1.2. Elements for Tourism Apps

3.2. Benchmarking

3.2.1. Selection of Applications

3.2.2. Comparative Analysis of Applications According to Garau’s Theoretical Model (2007)

3.3. User Research (UCD)

3.3.1. PHASE 1: Understanding and Specifying the Context of Use

Tourism Demand in the City of Riobamba

3.3.2. PHASE 2: Specifying User Requirements

User Personas

Design of the Data Collection Instrument

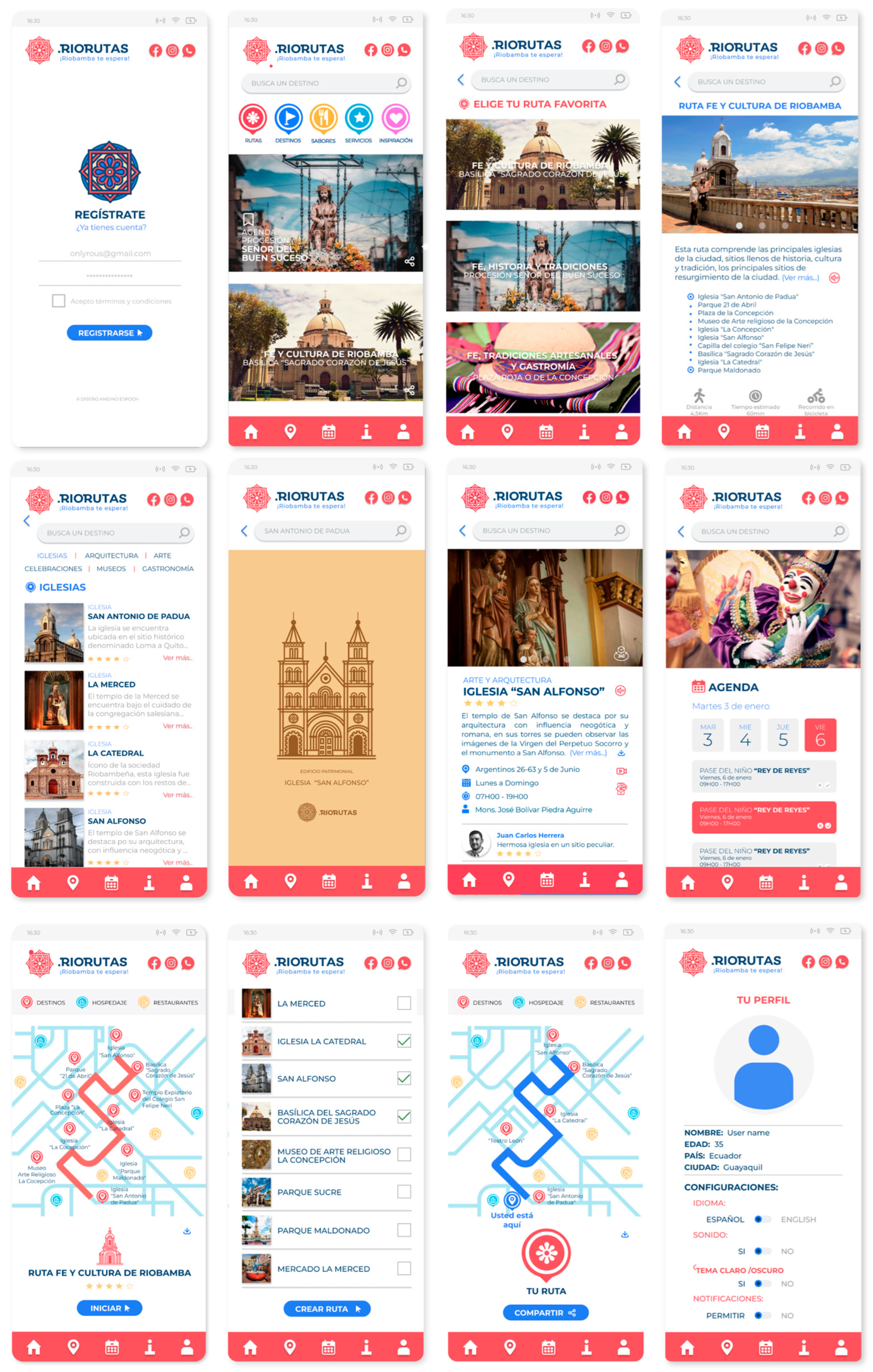

3.3.3. PHASE 3: Producing Design Solutions

Analysis and Interpretation of Results

Interpretive Dimension

Inclusive Dimension

Design Criteria Based on the Immersive Dimension

3.3.4. PHASE 4: Evaluation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ESPOCH | Escuela Superior Politécnica de Chimborazo |

| GADMR | Gobierno Autónomo Descentralizado Municipal de Riobamba |

| UNWTO | United Nations World Tourism Organization (Organización Mundial del Turismo) |

| ICTs | Information and Communication Technologies (Tecnologías de la Información y la Comunicación) |

| INPC | Instituto Nacional de Patrimonio Cultural |

| UCD | User-Centered Design (Diseño Centrado en el Usuario) |

| ISO | International Organization for Standardization |

| RA | Augmented Reality |

| UX | User Experience |

| UI | User Interface |

| ATMs | Automated Teller Machines |

| SUS | System Usability Scale |

| MVP | Minimum Viable Product |

| MoSCoW | Must, Should, Could, Won’t |

| CEN | Comité Europeo de Normalización CEN |

| W3C | World Wide Web Consortium |

| WCAG | Web Content Accessibility Guidelines |

Appendix A

| Criterion | Clio Muse Tours (International) | Visit City (International) | Valparaíso (Latin America) | VisitQuito (National) | Descubre Cuenca (National) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Visibility of system status | Quick and functional visual feedback, but error messages could be more descriptive. | Fast-loading and clear messages, though help is not always available. | No clear system status messages or error warnings. | Functional interactive geolocation, but lacks visual feedback in some processes. | Basic error messages, but unclear for preventing issues. |

| 2. Match between system and the real world | Intuitive language and symbols, though not all are universal. | Easy-to-understand icons and labels, but lacks specific cultural detail. | Detailed cultural descriptions, but lacks clear destination categorization. | Language focused on cultural heritage, but visual overload may hinder understanding. | Basic information without clear visual connection to local culture. |

| 3. User control and freedom | Flexible navigation and clear options, but too many choices can overwhelm. | Open exploration and flexible options, but long lists may confuse new users. | Clear maps, but no customization or favorite-saving options. | Lacks effective customization and incomplete user control functions. | Basic navigation: lacks recommended or customizable routes. |

| 4. Consistency and standards | Clean and consistent design, but limited language options affect international users. | Minimalist and consistent design, but weak visual identity. | Organized and consistent design but lacks deep cultural visual identity. | Graphic design with cultural elements, but visually overloaded in some sections. | Generic design with low visual impact or cultural connection. |

| 5. Error prevention | Allows destination exploration before purchase, though process simplification is needed. | Purchase process needs more clarity to prevent errors. | Does not prevent errors; no warnings or confirmation messages. | Lack of error prevention in incomplete or non-functional features. | Basic error messages, not effective in preventing issues. |

| 6. Recognition rather than recall | Intuitive icons and clear graphic design, but limited help in some sections. | Memorable icons, but weak graphic identity affects emotional connection. | High-quality photos and historical info help, but lacks functional categorization and customization. | Adequate visual representation of heritage, but lacks elements to reinforce user memory. | Scattered information and non-functional links affect recognition. |

| 7. Flexibility and efficiency of use | Efficient search and advanced customization, though overwhelming for new users. | Flexible options, language switch available. | Flexible options, language switch, personalized itineraries, and save favorites, but limited accessibility. | Interactive maps, language switch, but no customization or save options. | Lacks personalization options and functional routes. No flexible options like language switch. |

| 8. Esthetic and minimalist design | Clean and clear design; accessibility and readability could be improved. | Minimalist design with good contrast, but lacks a defined graphic identity. | Organized and minimalist design, but lacks a visual identity connecting with Valparaíso’s culture. | Sober interface with representative graphics, but overloaded in some sections. | Generic design without clear visual connection to cultural identity. |

| 9. Help users recognize and recover from errors | Clear error messages, but not very descriptive. | Helpful messages, but need more detail for non-technical users. | No error messages to help users recover from mistakes. | Lack of effective messages to guide users in error recovery. | Basic but inefficient error messages to guide users. |

| 10. Help and documentation | Functional help section, but not accessible in all areas. | Help is available, but not always accessible; location lacks consistency. | Limited help and lacks detailed documentation in key sections. | Partial help, not always available; functional multilingual support but incomplete. | Lacks a robust help section; information is basic and scattered. |

Appendix B

| Questions | Options | Profile 1 European | Profile 2 American | Profile 3 National |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. What types of activities are you interested in when visiting Riobamba? | a. Adventure activities in nature (Chimborazo, Altar, among others) b. Visits to heritage buildings, churches, and public squares c. Festivities and celebrations (Pase del Niño) d. Visits to museums and handicrafts e. Tasting local gastronomy | 18 | 15 | 16 |

| 14 | 10 | 10 | ||

| 10 | 16 | 8 | ||

| 12 | 15 | 13 | ||

| 20 | 20 | 20 | ||

| 2. What information would you like to be available in the app about Riobamba? | a. History and cultural background of the places b. Calendar of events and festivities c. Schedules and availability of activities d. Recommended routes e. Travel times and distances | 17 | 18 | 14 |

| 13 | 16 | 15 | ||

| 10 | 11 | 12 | ||

| 18 | 14 | 16 | ||

| 11 | 14 | 18 | ||

| 3. How important is it that content adapts automatically to your profile? | a. Highly important b. Moderately important c. Neutral d. Minimally important e. Not important | 20 | 15 | 12 |

| 0 | 5 | 6 | ||

| 0 | 0 | 2 | ||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 4. What additional information would you like to be available in the app? | a. Information on weather conditions b. User reviews and feedback c. Information on accessibility for individuals with disabilities d. Internet connectivity at tourist sites e. Basic services (hospitals, pharmacies, ATMs) | 9 | 7 | 10 |

| 16 | 12 | 17 | ||

| 7 | 8 | 7 | ||

| 15 | 10 | 12 | ||

| 16 | 15 | 14 | ||

| 5. How important is it that content includes stories or testimonies that humanize history? | a. Highly important b. Moderately important c. Neutral d. Minimally important e. Not important | 16 | 12 | 15 |

| 3 | 6 | 4 | ||

| 1 | 4 | 1 | ||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 6. What level of detail do you prefer in descriptions of heritage sites? | a. Brief descriptions (names and dates) b. Moderate detail, relevant information (basic data, brief historical context) c. Extensive detail, including historical and cultural information (basic data, historical and social context, cultural significance, symbolic value, curiosities, etc.) | 2 | 4 | 4 |

| 8 | 8 | 9 | ||

| 10 | 8 | 7 | ||

| 7. What services do you consider essential for a tourism app? | a. Restaurants, cafés, and bars b. Transportation c. Accommodation d. Tour operators and local guides e. Others | 15 | 14 | 13 |

| 12 | 14 | 15 | ||

| 14 | 13 | 12 | ||

| 5 | 2 | 3 | ||

| 3 | 4 | 4 | ||

| 8. What functionalities do you consider essential in a tourism app? | a. Geolocation for route tracking b. Multimedia content (photos, videos, audio) c. Sharing experiences on social media d. Itinerary planner e. Personalized recommendations f. Creation and customization of routes g. Language switching h. Marking favorite places | 18 | 19 | 17 |

| 16 | 14 | 12 | ||

| 10 | 17 | 15 | ||

| 10 | 11 | 8 | ||

| 7 | 8 | 9 | ||

| 13 | 14 | 12 | ||

| 18 | 12 | 6 | ||

| 16 | 8 | 6 | ||

| 9. How important is it that the app includes digital interaction resources? | a. Highly important b. Moderately important c. Neutral d. Minimally important e. Not important | 6 | 3 | 10 |

| 10 | 5 | 7 | ||

| 1 | 10 | 2 | ||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 1 | 2 | 1 | ||

| 10. What types of digital resources would you like the app to include? | a. Augmented reality for immersive experiences b. Virtual tours of cultural sites c. Tools such as QR codes d. Virtual characters/chatbots e. Gamified experiences (challenges to earn points or rewards for visiting certain places) f. Personalized recommendations based on user interests | 13 | 16 | 14 |

| 12 | 13 | 10 | ||

| 10 | 9 | 9 | ||

| 7 | 6 | 5 | ||

| 15 | 16 | 14 | ||

| 14 | 13 | 12 | ||

| 11. How important is it that the app promotes destination sustainability? | a. Highly important b. Moderately important c. Neutral d. Minimally important e. Not important | 5 | 3 | 4 |

| 6 | 7 | 5 | ||

| 9 | 8 | 10 | ||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 0 | 2 | 1 | ||

| 12. How important is accessibility for users with visual or hearing impairment? | a. Highly important b. Moderately important c. Neutral d. Minimally important e. Not important | 3 | 3 | 5 |

| 14 | 12 | 9 | ||

| 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 13. How important is it to include visual elements reflecting Riobamba’s cultural identity? | a. Highly important; it should be a central component b. Moderately important; it should be present in a balanced manner c. Neutral; I am indifferent to whether they are included or not d. Minimally important; I would prefer they not be included e. Not important; I do not wish for them to be included | 2 | 8 | 4 |

| 17 | 11 | 15 | ||

| 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 0 | 1 | 0 | ||

| 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 14. What type of visual elements do you prefer? | a. Colors, shapes, and textures inspired by local culture b. Photographs of attractions and activities c. Immersive videos of routes and attractions d. Icons representative of local culture e. Others | 18 | 19 | 17 |

| 16 | 15 | 14 | ||

| 8 | 9 | 10 | ||

| 14 | 13 | 12 | ||

| 10 | 9 | 8 |

References

- Bekele, H., & Raj, S. (2025). Digitalization and digital transformation in the tourism industry: A bibliometric review and research agenda. Tourism Review, 80(4), 894–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boes, K., Buhalis, D., & Inversini, A. (2016). Smart tourism destinations: Ecosystems for tourism destination competitiveness. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 2(2), 108–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D., & Amaranggana, A. (2015). Smart tourism destinations enhancing tourism experience through personalisation of services. In I. Tussyadiah, & A. Inversini (Eds.), Information and communication technologies in tourism 2015 (pp. 377–389). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D., & Foerste, M. (2015). SoCoMo marketing for travel and tourism: Empowering cocreation of value. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 4, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D., & Law, R. (2008). Progress in information technology and tourism management: 20 years on and 10 years after the Internet—The state of eTourism research. Tourism Management, 29(4), 609–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buri-Mendonza, E. J. (2023). Afiches pop art serigráficos para la promoción cultural de Riobamba [Bachelor’s thesis, Escuela Superior Politécnica de Chimborazo]. [Google Scholar]

- Cetin, G., & Bilgihan, A. (2016). Components of cultural tourists’ experiences in destinations. Current Issues in Tourism, 19(2), 137–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, N., Han, H., & Joun, Y. (2015). Tourists’ intention to visit a destination: The role of augmented reality (AR) application for a heritage site. Computers in Human Behavior, 50, 588–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciurea, C. (2015). Cultural heritage and mobile technologies—Towards a bibliography (1938–2015). Informatica Economică, 19(1), 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darcy, S., & Dickson, T. J. (2009). A whole-of-life approach to tourism: The case for accessible tourism experiences. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 16(1), 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dela Santa, E., & Tiatco, S. A. P. (2019). Tourism, heritage and cultural performance: Developing a modality of heritage tourism. Tourism Management Perspectives, 31(2), 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, J. E., Ghali, K., Cherrett, T., Speed, C., Davies, N., & Norgate, S. (2012). Tourism and the smartphone app: Capabilities, emerging practice and scope in the travel domain. Current Issues in Tourism, 17(1), 84–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez Vila, T., Alén González, E., & Darcy, S. (2018). Website accessibility in the tourism industry: An analysis of official national tourism organization websites around the world. Disabil Rehabil, 40(24), 2895–2906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Economou, M. (2015). Heritage in the digital age. In W. Logan, M. Nic Craith, & U. Kockel (Eds.), A companion to heritage studies (pp. 215–232). John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Telecommunications Standards Institute. (2021). Accessibility requirements for ICT products and services (EN 301 549 V3.2.1). ETSI. Available online: https://www.etsi.org/deliver/etsi_en/301500_301599/301549/03.02.01_60/en_301549v030201p.pdf (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Femenia-Serra, F., Neuhofer, B., & Ivars-Baidal, J. A. (2019). Towards a conceptualisation of smart tourists and their role within the smart destination scenario. The Service Industries Journal, 39(2), 109–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foronda-Robles, C., Mondeli, C., & Carboni, D. (2021). The role of the web and social media in the tourism promotion of a world heritage site. The case of the Alcazar of Seville (Spain). Revista de Estudios Andaluces, 41, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusté-Forné, F. (2016). Los paisajes de la cultura: La gastronomía y el patrimonio culinario. Dixit, 24(1), 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garau, C. (2016). Emerging Technologies and Cultural Tourism: Opportunities for a Cultural Urban Tourism Research Agenda. In N. Bellini, & C. Pasquinelli (Eds.), Tourism in the city. Springer. Available online: https://sites.unica.it/ghost/files/2020/01/11_Garau-Tourism-in-the-city.pdf (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- García-Crespo, Á., González-Carrasco, I., López-Cuadrado, J. L., & González, Á. (2016). CESARSC: Framework for creating cultural entertainment systems with augmented reality in smart cities. Computer Science and Information Systems, 13(2), 395–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazzola, P., Pavione, E., Grechi, D., & Ossola, P. (2018). Cycle tourism as a driver for the sustainable development of little-known or remote territories: The experience of the apennine regions of northern italy. Sustainability, 10(6), 1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobierno Autónomo Descentralizado de la Provincia de Chimborazo. (2015). Plan de desarrollo y ordenamiento territorial de la provincia de Chimborazo 2015. Available online: https://archivos.chimborazo.gob.ec/lotaip/ANEXOS/ANEXOS4/1.%20%20PDOT%20Chimborazo.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- González-Rodríguez, M. R., Díaz-Fernández, M. C., & Pino-Mejías, M. Á. (2020). The impact of virtual reality technology on tourists’ experience: A textual data analysis. Soft Computing, 24, 13879–13892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grevtsova, I. (2016). Interpretación del patrimonio urbano: Una propuesta didáctica para un contexto histórico mediante las aplicaciones de telefonía móvil [Ph.D. dissertation, Universitat de Barcelona]. Dialnet. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/tesis?codigo=79117 (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Hardy, A., Hyslop, S., Booth, K., Robards, B., Aryal, J., Gretzel, U., & Eccleston, R. (2017). Tracking tourists’ travel with smartphone-based GPS technology: A methodological discussion. Information Technology & Tourism, 17(3), 255–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, S. J. (2021). El turismo en la era digital: Las aplicaciones móviles como herramienta de innovación (Trabajo final de práctica profesional para la obtención del título en: LICENCIADO EN TURISMO) [Bachelor’s thesis, Universidad Nacional de San Martin, Escuela de Economía y Negocios]. [Google Scholar]

- International Organization for Standardization. (1999). Human-centred design processes for interactive systems (ISO 13407:1999). ISO. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/21197.html (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- International Organization for Standardization. (2012). Information technology—W3C Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.0 (ISO/IEC 40500:2012). ISO. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/58625.html (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- Ipiales Olmedo, D. C. (2023). Diseño de una ruta patrimonial turística relacionada al ámbito religioso de la zona urbana del cantón Riobamba, provincia de Chimborazo [Bachelor’s thesis, Polytechnic School of Chimborazo]. [Google Scholar]

- ISO. (2019). Ergonomics of human-system interaction—Part 210: Human-centred design for interactive systems (ISO 9241-210:2019). International Organization for Standardization.

- Koçyiğit, M., & Küçükcivil, B. (2022). Social media and cultural tourism. In E. P. Yiğit (Ed.), Handbook of research on digital communications, internet of things, and the future of cultural tourism (pp. 363–378). IGI Global. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourouthanassis, P., Boletsis, C., Bardaki, C., & Chasanidou, D. (2015). Tourists’ responses to mobile augmented reality travel guides: The role of emotions on adoption behavior. Pervasive and Mobile Computing, 18, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kravchenko, T., Bogdanova, T., & Shevgunov, T. (2022). Ranking requirements using MoSCoW methodology in practice. In Computer Science On-line Conference (pp. 188–199). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, L. (2010). Benchmarking y su aplicación en turismo. Polytechnical Studies Review, 8(14), 163–180. Available online: https://scielo.pt/pdf/tek/n14/n14a12.pdf (accessed on 13 July 2024).

- Marasco, A., Buonincontri, P., van Niekerk, M., Orlowski, M., & Okumus, F. (2018). Exploring the role of next-generation virtual technologies in destination marketing. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 9, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinakou, E., Giousmpasoglou, C., & Paliktzoglou, V. (2015). The Impact of Social Media on Cultural Tourism. In V. Benson, & S. Morgan (Eds.), Implications of social media use in personal and professional settings (pp. 231–248). IGI Global Scientific Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkono, M. (2016). The reflexive tourist. Annals of Tourism Research, 57, 206–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortara, M., Catalano, C. E., Bellotti, F., Fiucci, G., Houry-Panchetti, M., & Petridis, P. (2014). Learning cultural heritage by serious games. Journal of Cultural Heritage, 15(3), 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Municipio de Riobamba [GADMR] & Escuela Superior Politécnica de Chimborazo [ESPOCH]. (2021). Updated inventory of tourist attractions in the canton of Riobamba. GAD Municipal Riobamba & ESPOCH. [Google Scholar]

- Navío-Marco, J., Ruiz-Gómez, L. M., & Sevilla-Sevilla, C. (2018). Progress in information technology and tourism management: 30 years on and 20 years after the internet—Revisiting Buhalis & Law’s landmark study about eTourism. Tourism Management, 69, 460–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuhofer, B., Buhalis, D., & Ladkin, A. (2015). Smart technologies for personalized experiences: A case study in the hospitality domain. Electronic Markets, 25(3), 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T. K. C., & Vu, H. P. (2021). Studying tourist intention on city tourism: The role of travel motivation. International Journal of Tourism Cities. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, J. (1994). Usability engineering. Morgan Kaufmann. [Google Scholar]

- Norman, D. (1988). The design of everyday things. Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Pallud, J., & Straub, D. W. (2014). Effective website design for experience-influenced environments: The case of high culture museums. Information & Management, 51(3), 359–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papathanasiou-Zuhrt, D. (2024). Digital Heritage Narrative: Principles and Practice. The Case of the UNESCO-Listed Archaeological Site of Philippi, Greece. In A. Kavoura, T. Borges-Tiago, & F. Tiago (Eds.), Strategic innovative marketing and tourism (pp. 203–210). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazmiño Santillán, F. N. (2019). Competitividad turística de la ciudad de Riobamba valorada mediante análisis multivariante y alternativas para la consolidación como destino turístico [Master’s thesis, Escuela Superior Politécnica de Chimborazo]. Repositorio Digital ESPOCH. [Google Scholar]

- Pisoni, G., Díaz-Rodríguez, N., Gijlers, H., & Tonolli, L. (2021). Human-centered artificial intelligence for designing accessible cultural heritage. Applied Sciences, 11(2), 870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poria, Y., Reichel, A., & Biran, A. (2006). Heritage site perceptions and motivations to visit. Journal of Travel Research, 44(3), 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prats, L. (2011). La viabilidad turística del patrimonio. Pasos. Revista de Turismo y Patrimonio Cultural, 9(2), 249–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, A., & Morgan, N. (2017). Tourism’s lost leaders: Analysing gender and performance. Annals of Tourism Research, 63, 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, F. R., Silva, A., Barbosa, F., Silva, A. P., & Metrôlho, J. C. (2018). Mobile applications for accessible tourism: Overview, challenges and a proposed platform. Information Technology & Tourism, 19(1–4), 29–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, G. (2018). Cultural tourism: A review of recent research and trends. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 36, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez Jiménez, M. Á., & Ravina Ripoll, R. (2017). Análisis de las aplicaciones móviles de destinos turísticos y su accesabilidad. Teoría Y Praxis, 31, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schieder, T. K., Adukaite, A., & Cantoni, L. (2014). Mobile apps devoted to UNESCO World Heritage Sites: A map. In Z. Xiang, & I. Tussyadiah (Eds.), Information and communication technologies in tourism 2014 (pp. 17–29). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra Guillén, J. (2023). Mundos virtuales en el sector turístico: El metaverso [Master’s thesis, Tecnologías Aplicadas a la Gestión y Comercialización del Turismo, Universidad de Málaga]. [Google Scholar]

- Sierra Márquez, A. K., Ramos Pérez, L. E., & Zubiría Lara, M. F. (2021). Impacto socioeconómico y cultural del turismo de sol y playa en el Golfo de Morrosquillo 2016–2020. Tendencias, 22(2), 239–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotomayor Granda, M. F. (2019). Propuesta de difusión turística mediante herramientas web y estrategias de marketing digital. Caso de estudio: Cantón Loja, Ecuador. Siembra, 6(1), 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spendolini, M. J. (1992). The benchmarking process. Compensation & Benefits Review, 24(5), 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L., Pan, L., Wen, J., & Phau, I. (2022). Effects of tourism experiences on tourists’ subjective well-being through recollection and storytelling. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 28(4), 412–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timothy, D. J., & Boyd, S. W. (2003). Heritage tourism. Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- Timothy, D. J., & Nyaupane, G. P. (Eds.). (2009). Cultural heritage and tourism in the developing world: A regional perspective (1st ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tom Dieck, M. C., & Jung, T. (2018). A theoretical model of mobile augmented reality acceptance in urban heritage tourism. Current Issues in Tourism, 21(2), 154–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troncoso, C. A., & Almirón, A. V. (2005). Turismo y patrimonio. Hacia una relectura de sus relaciones. Aportes y Transferencias, 9(1), 56–74. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. (2023). Patrimonio cultural y turismo sostenible. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/tourism/ (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- UNWTO. (2023). UNWTO tourism definitions. World Tourism Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Urvina Alejandro, M. A., Lastra Bravo, X. B., & Jaramillo-Moreno, C. (2022). Turismo y aplicaciones móviles. Preferencias de turistas y prestadores de servicios en el cantón Tena, Napo, Ecuador. PASOS. Revista de Turismo y Patrimonio Cultural, 20(1), 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco González, M. (2009). Gestión turística del patrimonio cultural: Enfoques para un desarrollo sostenible del turismo cultural. Cuadernos de Turismo, 23, 237–253. Available online: https://revistas.um.es/turismo/article/view/70121 (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Vijayakumar, S., Krishna Prasad, K., & Ravikumar, R. (2024). Assessing the effectiveness of MoSCoW prioritization in software development: A holistic analysis across methodologies. EAI Endorsed Transactions on Internet of Things, 10(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Wide Web Consortium. (2018). Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.1. W3C. Available online: https://www.w3.org/TR/WCAG21/ (accessed on 7 August 2025).

| Characteristic | Description | Works |

|---|---|---|

| Authentic experiences | Values meaningful experiences connected to the cultural identity of the destination and emotional ties to heritage. | Timothy and Boyd (2003); Poria et al. (2006) |

| Participation | Seeks involvement in immersive activities such as visits to historical sites or cultural events. | Sierra Márquez et al. (2021); Richards (2018) |

| Alternative destinations | Prefers lesser-known places that offer unique experiences with historical value. | Gazzola et al. (2018) |

| Rejection of mass tourism | Avoids mass tourism in search of differentiated and more personal experiences. | Poria et al. (2006) |

| Sustainability awareness | Shows concern for sustainability and the environmental and social impact of their activities. | Gazzola et al. (2018) |

| Connection with local communities | Values relationships with local communities as a reinforcement of their sense of belonging. | Dela Santa and Tiatco (2019) |

| Appreciating local culture through food | Demonstrates interest in traditional expressions such as local cuisine. | Fusté-Forné (2016) |

| Component | Description | References |

|---|---|---|

| Authentic narratives | Contextualized information on tangible/intangible heritage (monuments, customs, gastronomy, etc.) through multimedia formats (text, maps, and AR) to enhance heritage understanding. | González-Rodríguez et al. (2020); Grevtsova (2016); Sierra Guillén (2023) |

| Community participation | User interaction via reviews, shared content, cultural games, and AR/QR tools. | Marinakou et al. (2015) |

| AI integration | Content sequencing and auto-captioning through machine learning. | Pisoni et al. (2021) |

| Practical info | Timely display of basic destination services and points of interest. | Dickinson et al. (2012) |

| Cultural calendar | Event and activity info with integrated booking. | Navío-Marco et al. (2018); Femenia-Serra et al. (2019) |

| Cultural esthetics | Visual interfaces reflecting the destination’s heritage identity. | Chung et al. (2015); González-Rodríguez et al. (2020) |

| Component | Description | Works |

|---|---|---|

| Intuitive and customizable interface | Interfaces that are intuitive and accessible to users with varying levels of technological proficiency. The UI should adapt to individual needs through font size, search, and bookmarks. | Hernández (2021); Pisoni et al. (2021) |

| Personalized itineraries | Customized heritage routes based on user preferences, interests, availability, and mobility. Includes thematic and inclusive design for different user profiles. | García-Crespo et al. (2016); Hardy et al. (2017); Sierra Guillén (2023) |

| User-generated content | Reviews, photos, and experiences shared by visitors as a complement to official information. | Buhalis and Foerste (2015); Su et al. (2022) |

| Universal design | Features that ensure usability for people with functional diversity, following Universal Design principles. | Domínguez Vila et al. (2018); Ribeiro et al. (2018); Darcy and Dickson (2009) |

| Offline functionality | The ability to function offline or with limited connectivity, especially for features like booking or navigation. | Ciurea (2015); Hernández (2021); Sierra Guillén (2023) |

| Multilingual support | Automatic or selectable assistance in multiple languages to eliminate language barriers. | Sierra Guillén (2023); Pisoni et al. (2021) |

| Cultural diversity and representation | Inclusive content that respectfully represents cultural diversity, avoiding stereotypes and promoting plural narratives. | Mkono (2016); Pritchard and Morgan (2017) |

| Component | Description | Works |

|---|---|---|

| Augmented reality experiences | Virtual reconstructions, historical recreations, or digital layers superimposed on real-world scenes (via camera or simulation), including labels, dates, or architectural details. | Kourouthanassis et al. (2015); Chung et al. (2015) |

| Immersive multimedia | Multimedia narratives combining images, text, and sound to present culture in a compelling and emotional way, optimized for platforms like Instagram or YouTube. | Koçyiğit and Küçükcivil (2022); Papathanasiou-Zuhrt (2024) |

| Immersive narrative integration | Structured storytelling combining digital and visual resources to contextualize heritage, enhance learning, and promote emotional engagement. | Papathanasiou-Zuhrt (2024); Su et al. (2022); Tom Dieck and Jung (2018); Mortara et al. (2014) |

| Communication strategy | Integration of social media and web platforms into a coherent communication strategy, using metrics to align content with audience interests. | Koçyiğit and Küçükcivil (2022); Buhalis and Law (2008) |

| Emotional interface design | Interactive elements that foster emotional connection and cultural identity, including chatbots or assistants offering content in various formats and languages. | Pallud and Straub (2014); Marasco et al. (2018); Sierra Guillén (2023); Pisoni et al. (2021) |

| Design Criteria | Functional Components | MoSCoW Priority | Evaluation Parameter (Technical Metric) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Ensure content quality | Accurate, culturally relevant information per site or route | Must-Have | >90% correct answers in post-reading quizzes per attraction; number of QR scans |

| Clear and simple language | Must-Have | ≥90% understand content without assistance (post-use interview) | |

| Multilingual support and language selector | Must-Have | ≥90% switch language without difficulty during guided task | |

| Physical signage with digital access via QR or NFC tags activating text, audioguides, AR, or other media | Must-Have | ≥80% access QR/NFC per point of interest | |

| 2. Define narrative logic of attractions and routes | Thematic storytelling per site or route | Must-Have | ≥90% identify main theme after guided task or thinking aloud |

| Classify narrative content types (legends, biographies, cultural practices, etc.) | Must-Have | ≥80% correctly identify narrative type (post-use survey) | |

| 3. Structure content | Standardized templates by content type (sites, routes, or services) | Should-Have | ≥85% navigate between templates without errors |

| Service and POI sections (lodging, ATMs, etc.) | Should-Have | ≥80% locate basic services without assistance | |

| Categorization by route or thematic itineraries | Should-Have | ≥80% access thematic itineraries during navigation test | |

| Progressive content layers via tabs or collapsible sections (“more info/less info”) | Could-Have | ≥75% use “see more/less” tabs at least once | |

| Thematic route builder | Should-Have | ≥70% create a personalized route without assistance | |

| Cultural events calendar | Should-Have | ≥60% interact with at least one event during testing | |

| 4. Promote gastronomy as a core tourism experience | Local gastronomy section | Should-Have | ≥80% explore section; high average scroll rate |

| Geolocated restaurant notifications | Could-Have | ≥60% interact after receiving notification | |

| Gamification (badges, coupons) | Could-Have | ≥40% redeem rewards at least once | |

| Co-created content with local actors (e.g., restaurants, producers, and cooks) | Could-Have | ≥20% mention interest in local content (interview) | |

| 5. Include useful information | POI identifiers (icons) | Must-Have | ≥85% identify icons correctly during guided tasks |

| Interactive maps with geolocated markers | Must-Have | ≥90% locate POIs accurately during navigation | |

| Functional data (travel time, distance, availability, schedules, and transport options) | Must-Have | ≥80% access key data without assistance | |

| 6. Incorporate cultural identity into content and design | Culturally rooted visual design (graphics or photo galleries) | Should-Have | ≥70% recognize at least two local graphic elements |

| Audiovisual testimonies from local actors and living heritage | Won’t-Have | ≥60% play at least one full testimonial |

| Design Criteria | Functional Components | MoSCoW Priority | Evaluation Parameter (Technical Metric) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Universal Design | Adaptive contrast | Must-Have | ≥90% report good text readability under bright light or background glare (post-use interview) |

| Scalable text size | Must-Have | ≥90% read easily using zoom (post-use interview) | |

| Intuitive icons (inspired by ISO 7001) with descriptive labels | Should-Have | ≥85% correctly identify icon/function unaided (think-aloud) | |

| Content Personalization | Personalized settings (language, cognition, text size, and contrast) | Should-Have | ≥70% configure profile correctly on first attempt (guided tasks) |

| Automatic UI adaptation based on profiles | Should-Have | Profiled users show reduced errors (A/B test + interview) | |

| Facilitate Offline Experience | Downloadable routes, content, and maps for offline use | Must-Have | ≥90% download and use content offline (guided tasks) |

| Incorporate User Content | Review section with distinct icons and typography | Could-Have | ≥20% contribute reviews, ratings, or comments (one-week test) |

| Integrated buttons to easily share opinions on social media | Could-Have | ≥30% click “Share” button (internal analytics) | |

| Organize Content by Processing Style | Structured content using headings, lists, graphics, and icons to support diverse cognitive styles | Should-Have | ≥80% answer comprehension questions correctly (post-reading quiz) |

| Multisensory options: read-aloud, subtitles, explanatory animations | Won’t-Have | ≥50% use audio/subtitles; ≥80% of content includes these options (post-use interview) |

| Design Criteria | Functional Components | MoSCoW Priority | Evaluation Parameter (Technical Metric) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Augmented Reality | 3D models activated via QR/geolocation | Should-Have | ≥70% access the model during the first guided test |

| Contextual information via AR | Won’t-Have | (excluded from first prototype) | |

| 2. Interface with Local Identity | Visual theme (textures, colors, patterns) reflecting local identity | Should-Have | ≥80% recognize at least one cultural graphic element (post-use interview) |

| Digital/physical signage with local identity | Must-Have | ≥90% locate the correct point using QR or physical signage (guided task) | |

| 3. Virtual Assistants | Chatbot with historical avatar | Could-Have | ≥50% of users interact with the avatar (free test) |

| Guided assistant led by local character | Could-Have | ≥60% complete the full guided route (task-based test) | |

| Automated profile-based suggestions | Must-Have | ≥70% click on at least one system suggestion during first session | |

| 4. Self-Guided Tours | Personalized route builder | Must-Have | ≥80% complete at least one custom route without errors |

| Interactive maps with POI markers | Must-Have | ≥90% correctly locate 3 key points during exploration task | |

| 5. Multimedia and Multisensory Content | Audio guides with ambient sounds triggered by QR or NFC | Should-Have | ≥60% play at least one track in the sound section |

| Navigable 360° views | Won’t-Have | Not applicable (excluded from first prototype) | |

| Interactive animations | Could-Have | ≥50% fully view at least one animation in multimedia section | |

| 6. Sustainability (Conservation) | Eco-labels in content | Could-Have | ≥40% identify eco-labels in viewed content |

| Information on environmentally friendly practices | Should-Have | ≥60% recall at least one practice (post-use interview) | |

| Conservation respect reminders | Won’t-Have | (excluded from first prototype) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ramos Jiménez, R.B.; Sanaguano Moreno, D.; Salazar Cazco, S.A.; Montúfar Guevara, S.P.; Cuadrado Solís, V.Y.; Heredia Sáenz, F.D. Criteria for the Design of Mobile Applications to Cultural Heritage Tourism: The Case of Riobamba. Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6040164

Ramos Jiménez RB, Sanaguano Moreno D, Salazar Cazco SA, Montúfar Guevara SP, Cuadrado Solís VY, Heredia Sáenz FD. Criteria for the Design of Mobile Applications to Cultural Heritage Tourism: The Case of Riobamba. Tourism and Hospitality. 2025; 6(4):164. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6040164

Chicago/Turabian StyleRamos Jiménez, Rosa Belén, Daniel Sanaguano Moreno, Steven Alejandro Salazar Cazco, Silvia Patricia Montúfar Guevara, Verónica Yasmín Cuadrado Solís, and Franklin David Heredia Sáenz. 2025. "Criteria for the Design of Mobile Applications to Cultural Heritage Tourism: The Case of Riobamba" Tourism and Hospitality 6, no. 4: 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6040164

APA StyleRamos Jiménez, R. B., Sanaguano Moreno, D., Salazar Cazco, S. A., Montúfar Guevara, S. P., Cuadrado Solís, V. Y., & Heredia Sáenz, F. D. (2025). Criteria for the Design of Mobile Applications to Cultural Heritage Tourism: The Case of Riobamba. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(4), 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6040164