Examining the Mediation Effect of Anti-Citizen Behaviour in the Link Between Job Insecurity and Organizational Performance: Empirical Evidence from Tunisian Hotels

Abstract

1. Introduction

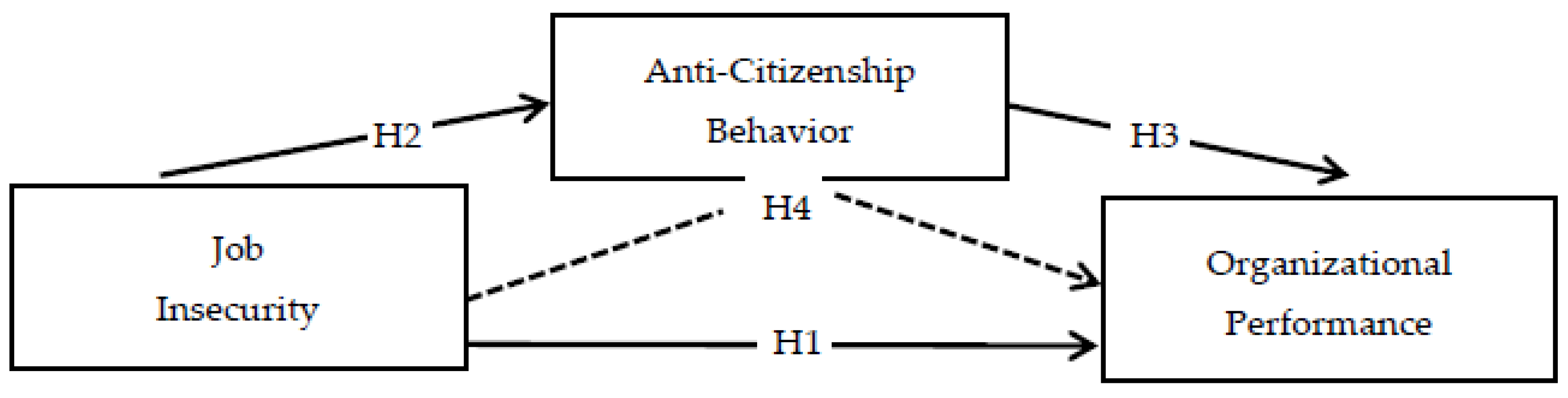

2. Operationalisation of Research Hypotheses

2.1. Job Insecurity and Organisational Performance

2.2. Job Insecurity and Anti-Citizen Behaviour

2.3. Anti-Citizenship Behaviour and Organisational Performance

3. Methodology

3.1. Measurement and Sample

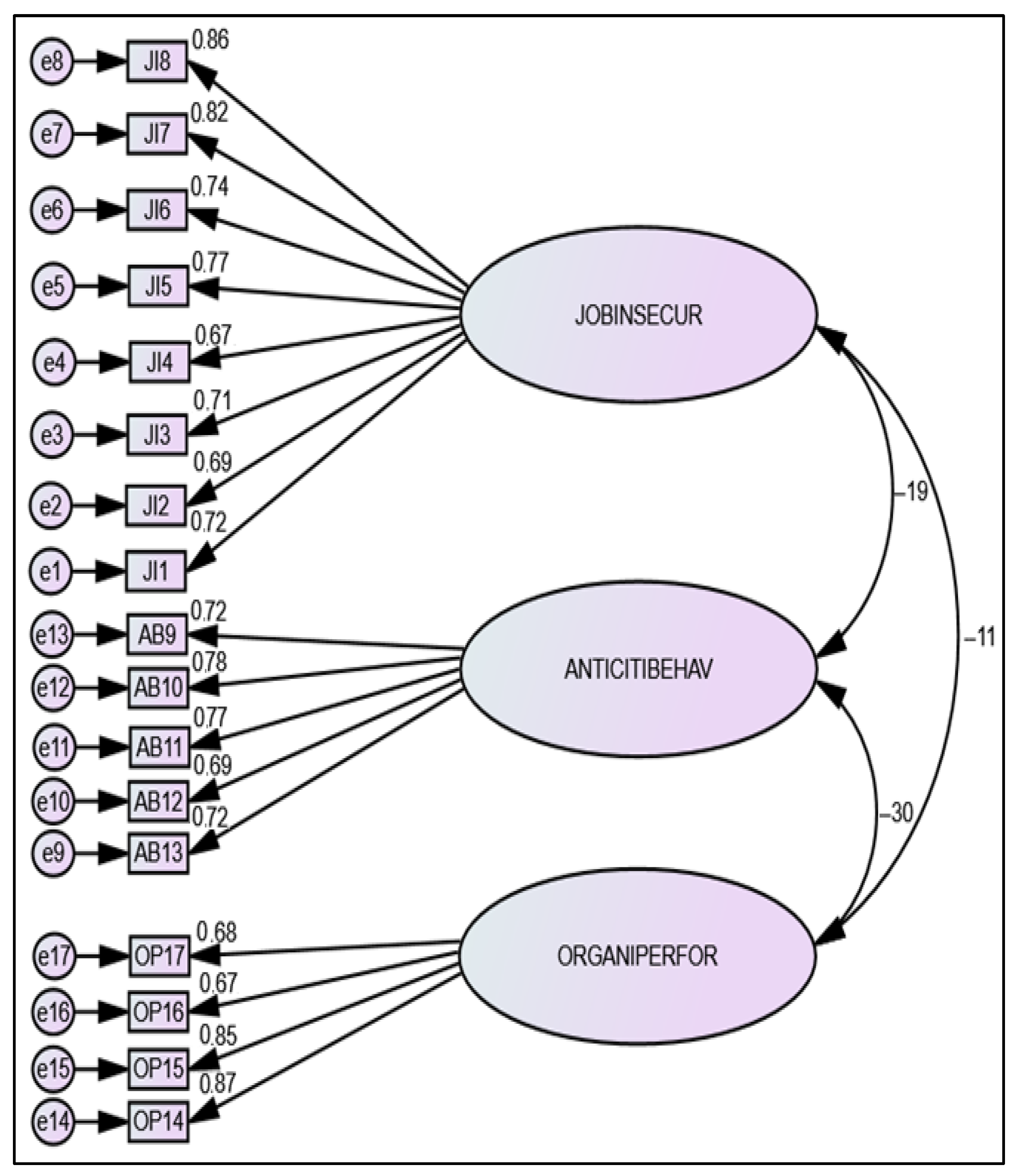

3.2. Purification of the Scales

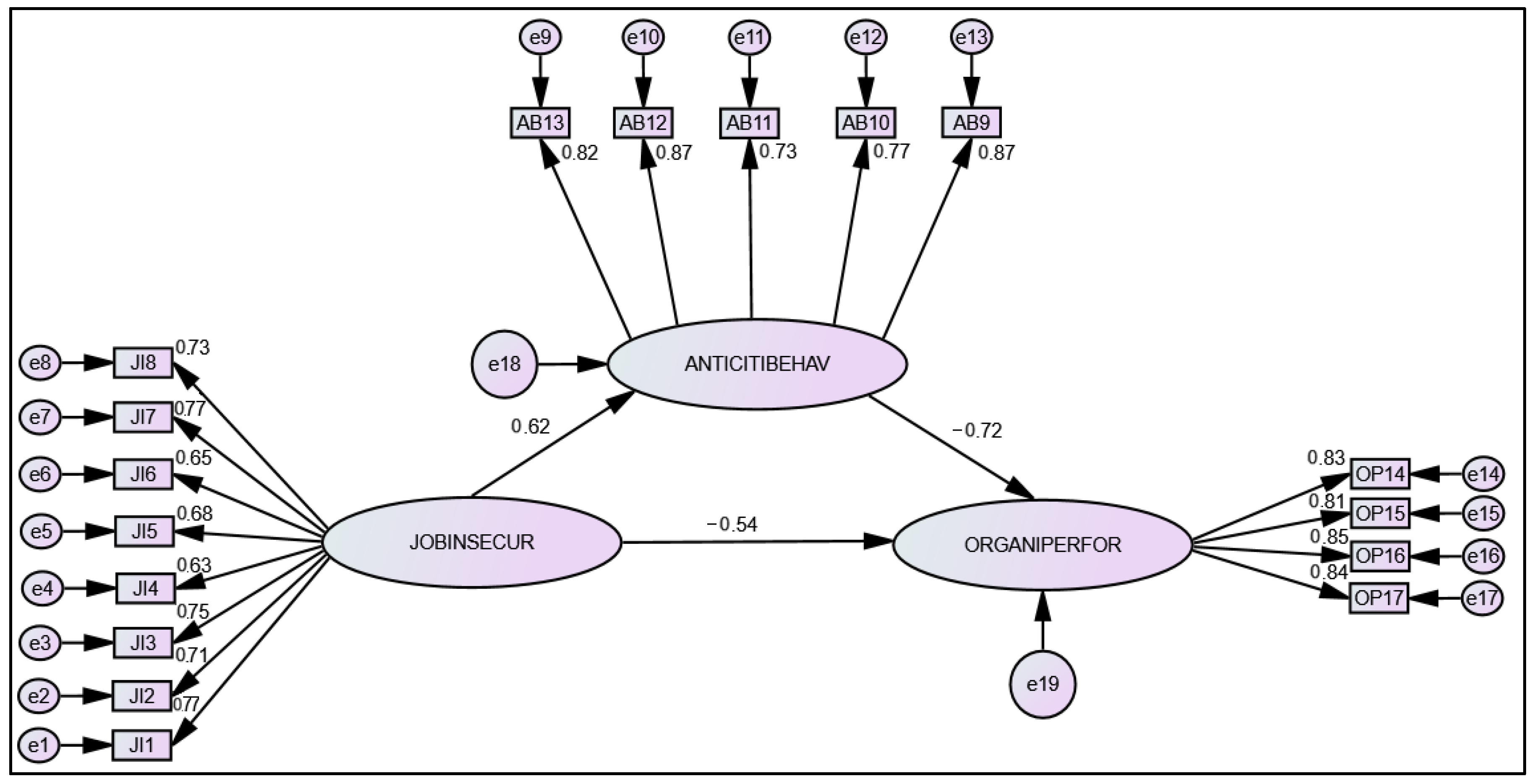

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Implications

7. Conclusions and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adekiya, A. (2024). Perceived job insecurity and task performance: What aspect of performance is related to which facet of job insecurity. Current Psychology, 43(2), 1340–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliane, N., Al-Romeedy, B. S., Agina, M. F., Salah, P. A. M., Abdallah, R. M., Fatah, M. A. H. A., & Khairy, H. A. (2023). How job insecurity affects innovative work behavior in the hospitality and tourism industry? The roles of knowledge hiding behavior and team anti-citizenship behavior. Sustainability, 15(18), 13956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliedan, M. M., Sobaih, A. E. E., Alyahya, M. A., & Elshaer, I. A. (2022). Influences of distributive injustice and job insecurity amid COVID-19 on unethical pro-organisational behaviour: Mediating role of employee turnover intention. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(12), 7040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alyahya, M. A., Elshaer, I. A., & Sobaih, A. E. E. (2021). The impact of job insecurity and distributive injustice post COVID-19 on social loafing behavior among hotel workers: Mediating role of turnover intention. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(1), 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alyahya, M. A., Sobaih, A. E. E., Gharbi, H., Aliane, N., & Bouzguenda, K. (2024). To leave or not to leave: Does trust really matter in the nexus between organizational justice and turnover intention among female employees? Journal of Infrastructure, Policy and Development, 8(5), 5077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong-Stassen, M. (1993). Production workers’ reactions to a plant closing: The role of transfer, stress and support. Anxiety, Stress and Coping, 6, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, G. A., Trevino, L. K., & Sims, H. P., Jr. (1994). Just and unjust punishment: Influences on subordinate performance and citizenship. Academy of Management Journal, 37(2), 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R. A. (1994). The physical environment of work settings: Effects on task performance, interpersonal relations, and job satisfaction. In B. M. Staw, & L. L. Cummings (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior (pp. 1–46). JAI Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bies, R. J., Shapiro, D. L., & Cummings, L. L. (1988). Causal accounts and managing organizational conflicts: Is it enough to say it’s not my fault? Communication Research, 15, 381–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P. (2017). Exchange and power in social life. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Blau, P. M. (1964). Justice in social exchange. Sociological inquiry, 34(2), 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, A., & Cramer, D. (2012). Quantitative data analysis with IBM SPSS 17, 18 & 19: A guide for social scientistsc. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, M. R. (2024). The moderating role of job insecurity on the relationship between psychological contract breach and employee turnover intention [Master’s Thesis, San Jose State University]. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, K., Molm, L. D., & Yamagishi, T. (1993). Exchange relations and exchange networks: Recent developments in social exchange theory. In J. Berger, & M. Zelditch Jr. (Eds.), Theoretical research programs: Studies in the growth of theory (pp. 296–322). Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Davy, J. A., Kinicki, A. J., & Scheck, C. L. (1997). A test of job security’s direct and mediated effects on withdrawal cognitions. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 18, 323–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Angelis, M., Mazzetti, G., & Guglielmi, D. (2021). Job insecurity and job performance: A serial mediated relationship and the buffering effect of organizational justice. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 694057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, R., Wu, J., & Xie, Y. (2025). Does teaching-research conflict affect research performance? The role of research stress, engagement and job insecurity. Cogent Education, 12(1), 2457907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folger, R., & Cropanzano, R. (1998). Organizational justice and human resource management. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Gheitarani, F., Nawaser, K., Hanifah, H., & Vafaei-Zadeh, A. (2024). Dimensions of anti-citizenship behaviours incidence in organisations: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Information and Decision Sciences, 16(3), 233–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholipour, A., Saeidinejad, M., & Zehtabi, M. (2009). The explanation of anti-citizenship behaviors in the workplaces. International Business Research, 2(4), 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacalone, R. A., Rosenfeld, P., & Riordan, C. A. (1997). Employee sabotage: Toward understanding its causes and preventing its recurrence. In R. A. Giacalone, & J. Greenberg (Eds.), Anti-social behavior in organizations (pp. 109–129). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, J. (1993). Stealing in the name of justice: Informational and interpersonal moderators of theft reactions to underpayment inequity. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 54, 81–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, L., & Rosenblatt, Z. (1984). Job insecurity: Toward conceptual clarity. Academy of Management Review, 3, 438–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J., Anderson, R., Tatham, R., & Black, W. (2014). Multivariate data analysis. Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Haldorai, K., Kim, W. G., & Phetvaroon, K. (2024). Job insecurity and survivor workplace behavior following COVID-19 layoff. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 36(1), 329–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S. E., Halbesleben, J., Neveu, J. P., & Westman, M. (2018). Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5(1), 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jangbahadur, U., Ahlawat, S., Rozera, P., & Gupta, N. (2025). The effect of AI-enabled HRM dimensions on employee engagement and sustainable organisational performance: Fusion skills as a moderator. Evidence-Based HRM: A Global Forum for Empirical Scholarship, 13(1), 85–107. [Google Scholar]

- Joreskog, K. G. (1988). Analysis of covariance structures. In R. B. Cattell, & J. R. Nessclroade (Eds.), Handbook of multivariate experimental psychology (pp. 207–230). Plenum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jöreskog, K. G., & Sörbom, D. (1989). Lisrel 7. A guide to the program and applications (2nd ed.). SPSS Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Kachali, H., Stevenson, J. R., Whitman, Z., Seville, E., Vargo, J., & Wilson, T. (2012). Organisational resilience and recovery for canterbury organisations after the 4 September 2010 earthquake. Australasian Journal of Disaster and Trauma Studies, 1, 11–19. [Google Scholar]

- Karatepe, O. M., Okumus, F., & Saydam, M. B. (2024). Outcomes of job insecurity among hotel employees during COVID-19. International Hospitality Review, 38(1), 101–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatepe, T. (2022). Do qualitative and quantitative job insecurity influence hotel employees’ green work outcomes? Sustainability, 14, 7235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. (2015). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, W., Li, J., Li, Y., Castano, G., Yang, M., & Zou, B. (2021). The boundary conditions under which teaching-research conflict leads to university teachers’ job burnout. Studies in Higher Education, 46(2), 406–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X., Huang, M., Liu, J., Fan, Y., & Cui, M. (2025). The impact of AI negative feedback vs. leader negative feedback on employee withdrawal behavior: A dual-path study of emotion and cognition. Behavioral Sciences, 15(2), 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, B. T., & Loosemore, M. (2017). The effect of inter-organizational justice perceptions on organizational citizenship behaviors in construction projects. International Journal of Project Management, 35(2), 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liouville, J., & Bayad, M. (1995). Stratégies de gestion des ressources humaines et performances dans les PME: Résultats d’une recherche exploratoire. Gestion 2000, 159–179. [Google Scholar]

- Marane, B. M. R., & Asaad, Z. A. (2025). The impact of job security on turnover intention: The moderating role of compensation system and performance appraisal in post COVID-19. International Review of Management and Marketing, 15(2), 285–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meckling, W. H., & Jensen, M. C. (1976). Theory of the firm. managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4), 305–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz Medina, F., López Bohle, S. A., Beurden, J. V., Chambel, M. J., & Ugarte, S. M. (2023). The relationship between job insecurity and employee performance: A systematic literature review and research agenda. Career Development International, 28(67), 589–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakra, N., & Kashyap, V. (2025). Responsible leadership and organizational sustainability performance: Investigating the mediating role of sustainable HRM. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 74(2), 409–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric theory (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, C. L., & Giacalone, R. A. (2003). Teams behaving badly: Factors associated with anti-citizenship behavior in teams. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 33(1), 58–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C., Peng, Z., Lin, J., Xie, J., & Liang, Y. (2025). How and when perceived COVID-19 crisis disruption triggers employee work withdrawal behavior: The role of perceived control and trait optimism. Personality and Individual Differences, 235, 112981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peretti, J. M. (2004). Les clés de l’équité de l’entreprise. Paris, Editions d’Organisation. Eyrolles Group. [Google Scholar]

- Piccoli, B., Reisel, W. D., & De Witte, H. (2021). Understanding the relationship between job insecurity and performance: Hindrance or challenge effect? Journal of Career Development, 48(2), 150–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probst, T. M. (2003). Development and validation of the job security index and the job security satisfaction scale: A classical test theory and IRT approach. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 76(4), 451–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puffer, S. M. (1987). Prosocial behavior, noncompliant behavior and work performance among commission salespeople. Journal of Applied Psychology, 72(4), 615–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaux, C. (2006). Emploi: Éloge de la stabilité (No. halshs-00202677). Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/p/hal/journl/halshs-00202677.html (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Robinson, S. L., & Bennett, R. S. (1995). A typology of deviant workplace behavior: A multidimensiona. Academy of Management Journal, 38, 555–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roussel, P., Durrieu, F., Campoy, E., & Akremi, A. (2005). Analyse des effets linéaires par modèles d’équations structurelles. Dans Management des Ressources Humaines, 11, 297–324. [Google Scholar]

- Sayles, L. R. (1958). Behavior of industrial work groups: Prediction and control. Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Semba, R. (2025). The effects of anger management on workers: A questionnaire survey of organizational dysfunctional behavior and withdrawal from interpersonal relationships in the Workplace. Behavioral Sciences, 15(2), 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobaih, A. E. E., Elshaer, I., Hasanein, A. M., & Abdelaziz, A. S. (2021). Responses to COVID-19: The role of performance in the relationship between small hospitality enterprises’ resilience and sustainable tourism development. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 94, 102824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobaih, A. E. E., Elshaer, I. A., & Abu Elnasr, A. E. (2025). Examining the impact of technological innovations on turnover intention of hotel employees: The mediating roles of job insecurity and job engagement. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality & Tourism, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobaih, A. E. E., Ibrahim, Y., & Gabry, G. (2019). Unlocking the black box: Psychological contract fulfillment as a mediator between HRM practices and job performance. Tourism Management Perspectives, 30, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommers, J. A., Schell, T. L., & Vodanovich, S. J. (2002). Developing a measure of individual differences in organizational Revenge. Journal of Business and Psychology, 17(2), 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, P. E. (2006). Method variance in organizational research: Truth or urban legend? Organizational Research Methods, 9(2), 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sverke, M., Hellgren, J., & Näswall, K. (2002). No security: A meta-analysis and review of job insecurity and its consequences. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 7(3), 242–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thévenet, M. (1992). Impliquer les personnes dans l’entreprise. Ed Liaisons. [Google Scholar]

- Thibaut, J. W., & Kelley, H. H. (1959). The social psychology of groups. John Wiley and Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Tsou, H. T., Chen, J. S., Mai, T. O., & Jade, N. B. N. (2025). Soft HRM practices fostering service innovations and performance in hospitality firms. Sustainability, 17(3), 895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardi, Y., & Wiener, Y. (1996). Misbehavior in organizations: A motivational framework. Organization Science, 7(2), 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T. J., Liang, Y., & Wang, Y. (2024). The buffering role of workplace mindfulness: How job insecurity of human-artificial intelligence collaboration impacts employees’ work–life-related outcomes. Journal of Business and Psychology, 39(6), 1395–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L. (2019). Teacher-researcher role conflict and burnout among Chinese university teachers: A job demand-resources model perspective. Studies in Higher Education, 44(6), 903–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Items | Class | Numbers | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 275 | 64.1 |

| Female | 154 | 35.9 | |

| Marital status | Married | 318 | 74.13 |

| Single | 111 | 25.87 | |

| Length of service in tourism | Less than 5 years | 36 | 8.39 |

| Between 6 and 10 years | 77 | 17.95 | |

| Between 11 and 15 years | 112 | 26.11 | |

| More than 15 years | 204 | 47.55 | |

| Age | <30 | 34 | 7.93 |

| 30–40 | 72 | 16.78 | |

| 41–50 | 240 | 55.94 | |

| >50 | 83 | 19.35 | |

| Income level | <1000 dt | 0 | 0 |

| 1001 dt–2000 dt | 101 | 23.54 | |

| 2001 dt–3000 dt | 265 | 61.77 | |

| >3000 dt | 63 | 14.69 | |

| Academic level | Professional diploma | 35 | 8.16 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 205 | 47.79 | |

| Bachelor’s degree plus 2 | 137 | 31.93 | |

| Bachelor’s degree plus 4 | 52 | 12.12 | |

| Have you witnessed any anti-citizen behaviour in your department or elsewhere in your hotel? | Yes | 328 | 76.46 |

| No | 101 | 23.54 | |

| Have you ever felt job insecurity in this hotel or elsewhere? | Yes | 341 | 79.49 |

| No | 88 | 20.51 | |

| Total | 429 | 100% |

| Abbreviation | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Standard Deviation | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Job Insecurity | ||||||

| JI1 | 1 | 5 | 4.09 | 1.177 | −1.265 | −1.269 |

| JI2 | 1 | 5 | 4.16 | 1.175 | −1.124 | −1.735 |

| JI3 | 1 | 5 | 4.25 | 0.961 | −1.081 | −1.627 |

| JI4 | 1 | 5 | 4.21 | 0.953 | −1.073 | 1.638 |

| JI5 | 1 | 5 | 4.26 | 0.982 | −1.043 | 1.623 |

| JI6 | 1 | 5 | 4.42 | 1.327 | −1.009 | 1.518 |

| JI7 | 1 | 5 | 3.39 | 1.432 | −0.956 | 1.365 |

| JI8 | 1 | 5 | 3.17 | 1.173 | −0.962 | −1.238 |

| Anti−citizenship Behaviour | ||||||

| ACB9 | 1 | 5 | 3.28 | 1.489 | −0.627 | −1.376 |

| ACB10 | 1 | 5 | 3.81 | 1.491 | −0.618 | −1.772 |

| ACB11 | 1 | 5 | 3.78 | 1.379 | −0.539 | −1.745 |

| ACB12 | 1 | 5 | 3.63 | 1.415 | −0.523 | −1.624 |

| ACB13 | 1 | 5 | 2.42 | 1.428 | −0.476 | −1.424 |

| Organisational Performance | ||||||

| OP14 | 1 | 5 | 1.73 | 1.002 | −1.276 | −1.163 |

| OP15 | 1 | 5 | 1.78 | 1.017 | −1.441 | −1.284 |

| OP16 | 1 | 5 | 2.15 | 1.025 | −1.482 | −1.633 |

| OP17 | 1 | 5 | 2.67 | 1.099 | −1.227 | −1.619 |

| Factors and Items | SL | CR | AVE | MSV | ASV | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1—Job Insecurity, (T. Karatepe, 2022) (α = 0.960) | 0.911 | 0.563 | 0.399 | 0.349 | 0.750 | |||

| JI1 | 0.86 | |||||||

| JI2 | 0.82 | |||||||

| JI3 | 0.74 | |||||||

| JI4 | 0.77 | |||||||

| JI5 | 0.67 | |||||||

| JI6 | 0.71 | |||||||

| JI7 | 0.69 | |||||||

| JI8 | 0.72 | |||||||

| 2—Anti-Citizenship Behaviour (Pearce & Giacalone, 2003) (α = 0.933) | 0.856 | 0.543 | 0.530 | 0.465 | 0.632 ** | 0.737 | ||

| ACB9 | 0.72 | |||||||

| ACB10 | 0.78 | |||||||

| ACB11 | 0.77 | |||||||

| ACB12 | 0.69 | |||||||

| ACB13 | 0.72 | |||||||

| 3—Organisational Performance (Kachali et al., 2012) (α = 0.930) | 0.854 | 0.598 | 0.530 | 0.415 | −0.548 ** | −0.728 ** | 0.773 | |

| OP14 | 0.68 | |||||||

| OP15 | 0.67 | |||||||

| OP16 | 0.85 | |||||||

| OP17 | 0.87 |

| Result of the Structural Model | β | C-R T-Value | Sig | R2 | Hypotheses Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1-JI → OP | 0.629 | 5.138 | *** | Supported | |

| H2-JI → ACB | −0.546 | −7.641 | 0.047 | Supported | |

| H3-ACB → OP | −0.725 | −9.118 | *** | Supported | |

| H4-JI → OP Through ACB | 0.552 |

| Parameter | Est | Lower Bounds (BC) | Upper Bounds (BC) | Tow Tailed Significance (BC) | Mediation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H4-JI → CB → OP | −0.381 | −0.410 | 0.029 | 0.067 | 0.067 > 0.05 Total Mediation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aliane, N.; Gharbi, H.; Sobaih, A.E.E. Examining the Mediation Effect of Anti-Citizen Behaviour in the Link Between Job Insecurity and Organizational Performance: Empirical Evidence from Tunisian Hotels. Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6040162

Aliane N, Gharbi H, Sobaih AEE. Examining the Mediation Effect of Anti-Citizen Behaviour in the Link Between Job Insecurity and Organizational Performance: Empirical Evidence from Tunisian Hotels. Tourism and Hospitality. 2025; 6(4):162. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6040162

Chicago/Turabian StyleAliane, Nadir, Hassane Gharbi, and Abu Elnasr E. Sobaih. 2025. "Examining the Mediation Effect of Anti-Citizen Behaviour in the Link Between Job Insecurity and Organizational Performance: Empirical Evidence from Tunisian Hotels" Tourism and Hospitality 6, no. 4: 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6040162

APA StyleAliane, N., Gharbi, H., & Sobaih, A. E. E. (2025). Examining the Mediation Effect of Anti-Citizen Behaviour in the Link Between Job Insecurity and Organizational Performance: Empirical Evidence from Tunisian Hotels. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(4), 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6040162