Abstract

The hospitality sector plays a crucial role in the tourism industry, undergoing a transformation driven by the intersection of service innovation and environmental practices. Competitiveness in this sector requires adaptation to market demands, with a focus on service innovation and environmental sustainability. This research aims to analyze the relationship between service innovation, environmental practices, and sustainable competitive advantage in Brazilian hospitality establishments. A quantitative and descriptive approach was applied to 300 individuals who stayed in Brazil. Data collection was conducted through an online questionnaire, utilizing the Snowball Sampling technique. The data collection was between 15 February and 20 June 2024. Data analysis was performed using Structural Equation Modeling, which enabled the examination of multiple variables and the verification of hypothetical relationships. The research results validated the hypotheses tested, demonstrating that service innovation and environmental practices have a positive influence on sustainable competitive advantage in hospitality establishments. An important finding in the research refers to the correlation between these constructs, which highlights the importance of integrated strategies that consider innovation and environmental sustainability as key elements for organizational success in the hospitality sector. With its theoretical contribution, this research developed a framework for analyzing the relationships between the constructs.

1. Introduction

Lodging facilities play a critical role in tourism development, as it is one of the most dynamic sectors in the global economy. Their evolution has been shaped by changes in consumption patterns, technological advancements, and growing environmental awareness among stakeholders. Within this context, the convergence of Service Innovations and Environmental Practices has emerged as a strategic factor of competitiveness in the lodging industry. Sustainable tourism, aligned with contemporary market demands, requires lodging establishments to adapt their business models to deliver distinctive guest experiences while preserving natural resources. As Mihalic (2024) highlights, external factors such as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), climate change, and the digitalization of tourism intensify the need for resilience and adaptability in the hospitality sector, thereby challenging both theoretical frameworks and practical implementations of sustainability in tourism.

Service innovation plays an essential role in the transformation of the hotel industry, influencing both the guest experience and the operational efficiency of companies. The studies presented by Liasidou and Pipyros (2025) introduce research related to aspects of technological innovations in tourism and the impact of emerging technologies, such as artificial intelligence. They also provide practical conclusions on the various ways in which technologies can transform and revolutionize the tourism industry. By embracing innovative strategies, hotel companies can differentiate themselves in the market and reinforce their long-term competitive advantage.

At the same time, growing concerns about sustainability have led hotels to adopt Environmental Practices as a strategic differentiator. Implementing initiatives such as energy efficiency, sustainable waste management, and carbon footprint reduction has become imperative to meet consumer expectations and comply with environmental regulations. Recent studies (Pereira-Moliner et al., 2021; Su et al., 2025) suggest that companies integrating sustainability into their operations mitigate negative environmental impacts, strengthen their corporate image, and increase customer loyalty. Therefore, sustainability should be seen as an ethical commitment and a source of competitive advantage that drives organizational performance.

Consumer preferences in the tourism sector also reflect a change toward more personalized and sustainable experiences. According to Brazil (2024b), there is an increasing demand for personalized and sustainable experiences, including exclusive itineraries and trips that promote engagement with nature. These changes in traveler behavior necessitate that lodging establishments restructure their services to provide authentic experiences that align with contemporary expectations. Customization and personalization of service, combined with responsible Environmental Practices, become important differentiators in cultivating customer loyalty and generating market value.

In Brazil, the tourism sector accounts for a substantial share of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP), contributing significantly to economic development and job creation. However, its reliance on traditional energy sources and increasing carbon emissions represent significant challenges to the sector’s sustainability. According to the World Bank (2023), Brazil is the third-largest energy consumer in the Western Hemisphere and faces mounting pressure to reduce carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions. In this scenario, lodging establishments assume a strategic role by adopting innovative Environmental Practices that enhance energy efficiency and mitigate environmental impact. Brazil’s commitment to reducing emissions by 50% by 2030 reinforces the importance of implementing sustainable solutions in the hotel industry.

The combination of Service Innovation and Environmental Practices allows hotels to build a Sustainable Competitive Advantage, setting themselves apart in the market and consolidating their relevance in the sector. Organizations that embed environmental responsibility into their core identity tend to attract more environmentally conscious consumers and strengthen stakeholder relationships. Moreover, ongoing service innovation enables the adaptation to emerging market demands, ensuring organizational resilience and sustainable long-term growth. In this sense, adopting innovative and sustainable strategies enhances competitiveness and contributes to the responsible development of the tourism sector.

Studies by Mahran et al. (2025) suggest that effective management plays a crucial role in implementing sustainability initiatives and enhancing the competitive advantage of organizations, as organizational leadership sets goals and outlines innovative and sustainable strategies. Therefore, leadership self-efficacy and innovative behavior influence organizational performance (Su et al., 2025).

In this context, the justification for this study lies in the importance of understanding the relationship between Service Innovation and Environmental Practices to obtain a Sustainable Competitive Advantage in lodging establishments, which contributes to filling the theoretical gap in studies related to environmental practices combined with innovativeness that result in better organizational performance, especially in emerging economies, such as Brazil.

In this sense, this research aims to analyze the relationship between service innovation, environmental practices, and sustainable competitive advantage in Brazilian hospitality establishments. By examining this interdependence, the research offers valuable insights for managers and policymakers, informing strategies that effectively integrate innovation, sustainability, and competitiveness in the hospitality sector.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Innovation

Innovation of products and services is a fundamental element for the sustainability of organizations (De Guimarães et al., 2021). Innovation is a strategic activity that can be systematically planned. In this sense, entrepreneurs are therefore responsible for identifying opportunities and mobilizing resources to make them a reality, leading to market expansion and value creation (De Guimarães et al., 2016; Goffin & Mitchell, 2022).

Innovation can be categorized into distinct types (Eurostat, 2018): (i) product innovation, which involves the introduction of new products or significant improvements to existing products; (ii) process innovation, which concerns new methods of production or distribution; (iii) market innovation, which covers entry into new segments; and, (iv) organizational innovation, which implies structural changes in business management.

Contemporary literature broadens this scope, recognizing that innovation may be driven by both internal factors and external pressures, such as competition and consumer expectations (Damanpour, 1991; Porter, 2008; Nambisan et al., 2019). Innovative companies differentiate themselves by adopting cutting-edge technologies, enhancing operational efficiency, and deploying innovative marketing strategies, ensuring a robust competitive position in the global marketplace (Teece, 2018).

In the context of Service Innovations, researchers such as De Guimarães et al. (2021) and Lee et al. (2021) emphasized the importance of introducing new processes and enhancing service delivery to meet evolving market demands. Service innovation is closely related to sustainable practices, personalized customer experiences, and the extensive use of technology (Gallouj et al., 2023).

Recent studies highlight the relationship between innovation and sustainability, emphasizing the role of technology and innovative management in reducing environmental impact and promoting sustainable business practices (Severo et al., 2018; Klein et al., 2023). In the hospitality sector, innovation has been instrumental in enhancing guest experiences through tools such as automated check-in systems, smart booking technologies, and eco-friendly practices. It is worth noting that the performance of companies in open innovation has made significant contributions to promoting innovation in services and business performance in the hotel sector (Hameed et al., 2021).

Innovation strategies encompass not only technological improvements but also social and sustainable aspects. Likewise, digital transformation has enabled the emergence of new business models and innovative management practices, contributing to organizational resilience (Nambisan et al., 2019; Hussein et al., 2024).

Thus, innovation remains a vital determinant of organizational success and sustainability, especially within the tourism and hospitality industries. Companies that embrace innovation can enhance service quality, reduce operational costs, and add value to the customer experience, thereby securing a differentiated competitive position in the global market (De Guimarães et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2025).

2.2. Service Innovation in Lodging Establishments

Service innovation can be defined as a “new service,” which is the most common interpretation; however, a company can also introduce innovations within its existing services, broadening the definition of service innovation (Witell et al., 2016). Despite its recognized significance for organizational performance, the literature on service innovation remains fragmented, with no universally accepted definition (Den Hertog et al., 2010; De Guimarães et al., 2016).

Service Innovation refers to changes that are directly perceived by the customer and regarded as new, either because they are entirely novel or recently implemented by the company (Hjalager, 2010; Gomezelj, 2016). This type of innovation can be a critical factor for competitive advantage, economic progress, and social transformation (Lee et al., 2021).

The Oslo Manual (Eurostat, 2018) emphasizes the importance of collaboration and co-creation with customers and external partners in the service innovation process. Inter-organizational collaboration is a crucial factor in achieving successful innovation outcomes, thereby enhancing a company’s ability to respond to dynamic market needs.

Service innovation in the lodging sector is fundamental to the competitiveness and growth of organizations. Studies indicate that innovation significantly enhances financial and operational performance (De Guimarães et al., 2016; Severo et al., 2020). In the tourism industry, innovation is widely recognized as essential for organizational survival (Pikkemaat, 2008; Hjalager, 2010; Paget et al., 2010).

The hospitality industry has invested in innovations, as there is a direct relationship of influence between service innovation and sustained competitive advantage (Tajeddini et al., 2024). Adopting new technologies and innovative strategies is seen as a key differentiator in enhancing competitiveness in the hospitality market (Barney, 1991; De Guimarães et al., 2021). Studies suggest that customers appreciate innovative hospitality services (Chen & Tung, 2014; Pikkemaat et al., 2019), and the expectation for innovations is rising, which can positively influence the organization’s performance (Kallmuenzer, 2018; Tajeddini & Trueman, 2012).

Given the sector’s high degree of customer interaction, innovation plays a critical role in improving service delivery and differentiating the guest experience (Dzhangzhugazova et al., 2016; Gomezelj, 2016). Notable examples of innovation in the industry include personalized services, wellness-oriented infrastructure (Pikkemaat, 2008), and sustainable practices (Le et al., 2006).

The competitive advantage of hotel companies is directly linked to their capacity for innovation and positive impact on market positioning and customer satisfaction (Hossain et al., 2021). Therefore, effective innovation management becomes essential for the success and competitiveness of lodging facilities in the global market.

2.3. Environmental Practices in Lodging Facilities

The growing demand for sustainability across industries, including the tourism and hospitality sector, has led companies to adopt Environmental Practices in response to regulatory requirements and social and market expectations. Since the 1970s, the European Union has implemented environmental policies that establish minimum standards for waste management and pollution control (Erdogan & Baris, 2007). With increased awareness of sustainable development, Environmental Practices have come to be seen not only as an ethical responsibility but also as a strategic opportunity for companies, since environmental protection is one of the priority tasks for modern organizations (Porter & Van der Linde, 1995; Su et al., 2025).

Within this context, Environmental Practices play a fundamental role in the financial performance of companies. The adoption of sustainable technologies, such as waste management systems and the efficient use of natural resources, contributes to cost reduction and process improvement (Babiak & Trendafilova, 2011; Severo et al., 2020). In addition, environmental certifications, such as ISO 14001 (Brazil, 2024c), provide a competitive advantage by facilitating regulatory compliance and enhancing corporate reputation, which in turn attracts sustainability-conscious consumers and investors (Severo & De Guimarães, 2022).

In the lodging sector, although hotels and similar establishments may not cause the same level of environmental degradation as other industries, their operations consume significant amounts of resources, such as water and energy, and generate substantial waste. This makes the adoption of Environmental Practices both necessary and impactful (Mensah & Blankson, 2013; Chan, 2013). In this context, implementing Environmental Practices in hotels and other lodging facilities is not only a matter of corporate social responsibility but also a green marketing strategy that enhances customer satisfaction and strengthens brand loyalty (Chen & Tung, 2014; Cheng et al., 2022; Xiao et al., 2025).To achieve this, it is necessary to seek consumer engagement, as this experience influences customer loyalty (Taheri et al., 2025).

Adopting Environmental Practices in lodging establishments can be better understood through several theoretical frameworks that explain organizational behavior and consumer motivation. Among the most widely applied theories are the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA), the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), and the Resource-Based View (RBV):

- (a)

- Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA): This theory seeks to understand how attitudes and social norms influence the intention of organizations to adopt Environmental Practices. It is also helpful in designing strategies that promote engagement and raise awareness about the importance of sustainable behavior (Ajzen, 1991; Chan, 2013). Studies by Sanjay et al. (2025) included in the TRA examined behavioral intentions related to psychological variables, including perceived environmental awareness, green confidence, pro-environmental self-identity, and environmental concern. Organizational strategy, as well as the TRA, contributes to successful hotel accommodation reservations (Mensah & Blankson, 2013). These studies corroborate hypothesis H2 (Environmental Practices have a positive impact on Sustainable Competitive Advantage in lodging establishments).

- (b)

- Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB): TPB is a useful tool for understanding and predicting consumer behavior in relation to Environmental Practices, allowing for the development of interventions that modify behaviors that are harmful to the environment. Studies have shown that individual attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control all significantly affect consumers’ decisions to choose hotels that adopt green practices (Ajzen, 1991; Chen & Tung, 2014; Cheng et al., 2022). The TPB, through its cognitive (awareness and knowledge) and affective (emotions and concern) components, can influence consumer attitudes towards sustainability and green innovations (Wiśniewska et al., 2025), which reinforces the possibility of a relationship expressed in H2 of this study.

- (c)

- Resource-Based View (RBV): This theory emphasizes the strategic value of an organization’s internal resources and capabilities as sources of sustainable competitive advantage. Consequently, strategic resources that are valuable, rare, inimitable, and non-substitutable lead to a sustainable competitive advantage (Barney, 1991). The application of RBV principles in developing a competitive advantage through investment in environmental practices yields significant results in organizational performance (Su et al., 2025). These studies cooperate with the formulation of research hypothesis H2.

Another relevant aspect about environmental practices is that they can be related to process innovation (waste management, conservation projects) and are associated with better performance measures in hotels (Herzallah et al., 2025; Xiao et al., 2025).

2.4. Sustainable Competitive Advantages in Lodging Facilities

Sustainable environmental practices in lodging facilities contribute to environmental preservation and building a competitive advantage in the market. The results of Fatoki’s (2021) studies showed that environmental orientation and green competitive advantage are significantly positively related, which improves the company’s image. Moreover, these practices can reduce operational costs, attract environmentally conscious consumers, strengthen stakeholder relationships, and improve long-term financial performance (De Guimarães et al., 2021).

The adoption of Environmental Practices in lodging facilities is a strategic approach that supports both environmental sustainability and organizational performance. Applying the theoretical frameworks to understand organizational and consumer behavior provides valuable insights into how companies can implement more effective and impactful environmental practices. Moreover, these initiatives not only address regulatory and societal expectations but also foster a competitive advantage by attracting environmentally conscious consumers and enhancing brand reputation.

2.5. Framework and Hypotheses

Innovation is widely recognized as a critical source of competitive advantage for companies (Porter, 2008; De Guimarães et al., 2016). Both authors emphasize that organizations must continually seek new ways to create value for customers, whether through innovative products or distinctive services. Differentiation through innovation enables companies to establish a unique market position, making it challenging for competitors to replicate their offerings (Porter, 2008).

In the context of lodging facilities, Service Innovations can take multiple forms, including personalized guest services, the adoption of advanced technologies to enhance the customer experience, and the implementation of more efficient operational practices that not only reduce costs but also minimize environmental impacts. According to Barney (1991), strategic resources, such as innovation capability, can be sources of Sustainable Competitive Advantage, as long as they are valuable, rare, difficult to imitate, and non-substitutable.

Recent studies have further linked service innovation not only to competitive differentiation but also to organizational sustainability (De Guimarães et al., 2021; Alreahi, 2023). Sharma and Vredenburg (1998) suggest that companies that innovate in their service offerings can develop distinctive organizational capabilities, especially when such innovations are aligned with social and environmental responsibility practices. Service innovation allows organizations to adjust their strategies to environmental changes, as well as allowing them to develop new products (service innovation), refine internal processes, and adapt to evolving market conditions (De Guimarães et al., 2021; López-Gamero et al., 2023b). In this regard, a proactive environmental strategy integrated with innovation favors organizational competitiveness (Fraj et al., 2015).

Service innovation has become a key driver of improved environmental performance in the hospitality industry. In the study by Lopes and Basso (2023), evidence was found that adopting eco-innovation improves the performance of companies in the hotel sector in Brazil, through the generation of competitive advantage.

Empirical evidence supports the notion that investment in Service Innovation can attract more customers, increase satisfaction, and lead to operational efficiencies (Gebauer et al., 2010; Putra & Putri, 2019). Service quality has positive and significant direct and indirect effects on customer loyalty through relationship marketing (Putra & Putri, 2019). Based on the literature, hypothesis H1 was developed:

H1.

Service Innovation positively influences Sustainable Competitive Advantage in lodging facilities (SIN → SCA).

Environmental Practices in lodging facilities have gained increasing importance due to heightened awareness of environmental issues and rising regulatory and social pressure from customers and stakeholders. The adoption of such practices extends beyond mere compliance with environmental regulations; it also involves proactive strategies aimed at mitigating the negative environmental impacts of hotel operations. These strategies include reducing energy and water consumption, implementing proper waste management systems, and using sustainable materials in the construction and daily operation of hotels (De Guimarães et al., 2020; Molina-Collado et al., 2022).

The benefits of adopting Environmental Practices are varied and cover economic, social, and environmental dimensions. In economic terms, these practices can lead to significant long-term cost savings, particularly through reductions in utility expenses. Empirical studies show that hotels implementing energy-efficient Technologies can lower operational costs and improve financial performance (Gössling et al., 2021).

In terms of competitiveness, Environmental Practices can act as a strategic differentiator. Achieving recognized certifications—such as LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) or other sustainability accreditations—enables hotels to stand out in a crowded marketplace, appeal to the growing segment of conscious consumers, and strengthen their overall brand reputation (De Guimarães et al., 2020; Molina-Collado et al., 2022). From the literature review, hypothesis H2 emerges.

H2.

Environmental Practices have a positive impact on Sustainable Competitive Advantage in lodging establishments (EP → SCA).

Service Innovation is also recognized as a catalyst for enhancing the environmental performance of organizations. This concept extends beyond the mere introduction of new services, encompassing cultural aspects, the promotion of creativity and, above all, the integration of sustainable Environmental Practices (Shrivastava, 1995; López-Gamero et al., 2023b).

Empirical studies confirm that Service Innovation significantly contributes to the differentiation and enhancement of brand reputation in hospitality organizations, especially When such innovations are aligned with sustainable Environmental Practices (Chen & Tung, 2014; Latif et al., 2020; Severo et al., 2019; López-Gamero et al., 2023a). The literature further suggests a positive relationship between service innovation and customer satisfaction, behavioral intentions, and trust (Ali et al., 2018; Martínez et al., 2014).

Hotels that adopt Environmental Practices not only improve their corporate image but also increase their legitimacy in the market by positioning themselves as leaders in environmental responsibility (Severo et al., 2020). Environmental Practices are fundamental to building a positive image of the hotel, which can attract conscious customers and foster long-term consumer loyalty (Latif et al., 2020; López-Gamero et al., 2023a). Based on the precepts found in the literature, hypothesis H3 was developed:

H3.

There is a positive correlation between Service Innovation and Environmental Practices in hotels (SIN → EP).

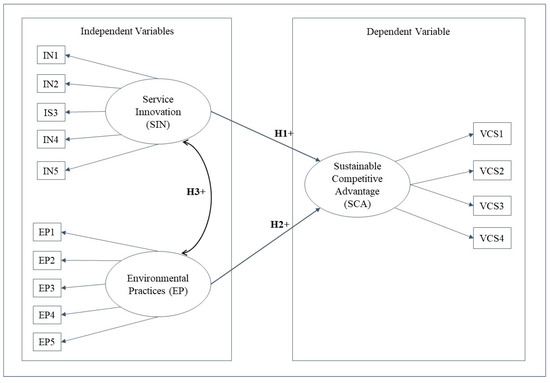

The interdependence between Service Innovation and Environmental Practices is crucial in the lodging sector. Effective environmental management not only improves service quality but also creates new experiences that increase customer satisfaction and trust (Chen & Tung, 2014; Putra & Putri, 2019). Figure 1 presents the research’s Theoretical Model (Framework).

Figure 1.

Theoretical model analyzed in the study.

3. Method

The research adopted a quantitative approach to collect numerical data and analyze the relationships between variables. A quantitative methodology was chosen for its ability to produce generalizable results, particularly suitable for analyzing similar contexts. A survey was used as the primary data collection instrument due to its effectiveness in capturing structured responses from a broad sample.

Surveys are one of the most widely used tools in quantitative research, especially when aiming to map the characteristics or behaviors of a specific population. They consist of standardized questions applied in a consistent manner to a group of respondents. This study adopted a descriptive approach, focusing on mapping the distribution of traits among respondents rather than seeking in-depth causal explanations.

The target population consisted of individuals who had previously stayed at lodging facilities in Brazil, including hotels, inns, and similar establishments within the hospitality sector. The sample was collected through non-probability convenience sampling, a technique in which participants are selected based on their availability and willingness to participate, rather than through random or representative selection (Hair et al., 2014).

A minimum sample size of 200 respondents was defined, following Kline’s (2023) recommendations to ensure statistical validity of the results, even in non-probability samples, and to meet the minimum requirements for conducting Structural Equation Modeling.

Data were collected using an online questionnaire applied through the Google Forms platform. The survey was shared via social media platforms (Facebook, LinkedIn, Instagram, WhatsApp) and email. Initially, the questionnaire was sent to respondents that the researchers had access to, i.e., a convenience collection. However, in order to reach the research objectives and expand the sample, the first respondents were asked to send it to their contacts, characterizing the Snowball method as the main form of data collection. This method is particularly effective for reaching hard-to-locate populations (Severo et al., 2020), such as tourists and hotel guests.

The snowball sampling technique was selected for data collection due to its effectiveness in reaching specific and hard-to-access populations. This technique was used because a large sample with hundreds of respondents was necessary to meet the research objectives. The data collection was between 15 February and 20 June 2024. It is worth noting that Table 1 presents Convergent Validity and Discriminant Validity, which are the correlations between the constructs formed by the observable variables (questionnaire). The survey instrument was structured (questionnaire) based on insights from the literature review and is shown in Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4. The questions were based on: (i) Service Innovations (SIN)—adapted from De Guimarães et al. (2016), Eurostat (2018), Hjalager (2010), Gomezelj (2016), and Severo et al. (2020); (ii) Environmental Practices (EP)—adapted from: Pagell and Gobeli (2009), Yang et al. (2010), Severo et al. (2018) and Severo et al. (2020); (iii) Sustainable Competitive Advantage (SCA)—adapted from Wernerfelt (1984), Barney (1991), De Guimarães et al. (2016), and Severo et al. (2018).

The questionnaire features a five-point Likert scale, enabling respondents to indicate their degree of agreement or disagreement with the presented statements, ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree). This scale is widely used in social research due to its simplicity and ease of data interpretation (Joshi et al., 2015). After developing the questionnaire, it was validated by four experts in the fields of innovation, sustainability, tourism, and hospitality, who suggested adjustments to ensure the clarity and accuracy of the observed variables. The final version of the questionnaire was refined based on the feedback from four experts and tested through a pre-test with 22 respondents.

Structural Equation Modeling (SEM), an advanced multivariate analysis technique that enables the investigation of complex relationships between latent and observable variables, was used to analyze the data. SEM was chosen for its capacity to simultaneously analyze multiple dependent and independent variables, thereby allowing the theoretical model’s validity to be assessed through Variable interactions (De Guimarães et al., 2016).

The following are the main steps for applying the SEM method and the statistical parameters to evaluate the results of the Multivariate Data Analysis calculations:

- (a)

- Normality and simple reliability of observable variables (Mardia, 1971; Bentler, 1990; Kline, 2023; Hair et al., 2014; De Guimarães et al., 2023): (i) Bartlett’s test of sphericity (Significance level p < 0.001); (ii) Cronbach’s alpha (>0.7); (iii) Kurtosis index (Mardia’s coefficient > 5); (iv) Pearson’s Coefficient of Skewness (close to Zero); (v) Factor loadings (≥0.5); (vi) Commonality (≥0.5); (vii) Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) (>0.5); and (viii) Composite Reliability (>0.7); (ix) Multicollinearity (Pearson’s correlation ≥ 0.7); (x) Average Variance Extracted (AVE)—Convergent Validity (CV) (>0.7) and Discriminant Validity (less than CV).

- (b)

- Hypotheses of the relationship between constructs (De Guimarães et al., 2016; Severo et al., 2018). The hypotheses were tested with the evaluation of the Standardized Estimates (SE) indexes, in which the intensity of the relationships between the constructs and the significance level (p > 0.05) was verified. To assess the intensity of the relationships, the following parameters were used: (i) IF less than 3.0 is low intensity; (ii) values between 0.3 and 0.5 moderate intensity; (iii) values greater than 0.5 high intensity;

- (c)

- Evaluation of the quality of the measurement model and the structural model (Bentler & Bonett, 1980; Fornell & Larcker, 1981; Tanaka & Huba, 1985; Bollen, 1989; Bentler, 1990; McDonald & Marsh, 1990; Hair et al., 2014): (i) Chi-square value (χ2) of the estimated model divided by Degrees of Freedom (DF) (χ2/DF ≤ 5); (ii) Root Mean Squared Error of Approximation (RMSEA) (between 0.05 and 0.08); (iii) Normed Fit index (NFI) (≥0.90); (iv) incremental fit index (IFI) (values close to 1.0); (v) Tucker–Lewis coefficient (TLI) (values close to 1.0); (vi) Comparative Fit Index (CFI) (values close to 1.0); (vii) RMR—Root Mean Square Residual (The smaller the better).

SEM was performed using AMOS (version 24.0) and SPSS Statistics (version 26) software. These tools support the construction of path models that illustrate the relationships between variables and facilitate the analysis.

It is important to note that this research involves human beings. Therefore, at the beginning of the questionnaire, respondents were informed through a text about the concept of “Free and Informed Consent.” However, since this is not a survey involving physical or psychological manipulation of human subjects, the text stated that there would be no risks associated with responding to the survey. It emphasized that the survey results would be analyzed and published, ensuring that respondents’ identities would not be disclosed, as they would be kept confidential in accordance with Brazilian law (Brazil, 2024a).

4. Results

After collection, the data were organized and tabulated in SPSS Statistics (version 26) software, with the exclusion of 3 questionnaires that had answers concentrated in a single question, considered outliers. The final sample consisted of 297 valid questionnaires, exceeding the minimum criteria of 200 respondents for using the Structural Equation Modeling methodology (Hair et al., 2014; Kline, 2023).

The Z-score test was conducted to assess data normality. Several variables—SIN1, SIN4, SIN5, EP2, EP4, EP5, and SCA1—showed Z-scores beyond the |3| limit, indicating potential deviations from normality. These anomalies were further confirmed by calculating the KMO.

Subsequently, Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was performed, incorporating both Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) and Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA). These methods were used to uncover the data’s latent structure and to evaluate the extent to which theoretical constructs aligned with empirical observations, consistent with the approach outlined by Byrne (2013).

Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was first applied to identify correlations among observed variables and to group them into latent constructs, thereby reducing data complexity and uncovering underlying patterns. Following this, CFA was employed to assess the model’s fit and test whether the data reliably supported the theoretical constructs.

All constructs demonstrated Composite Reliability (CR) scores exceeding 0.7, in line with Marôco (2010), confirming internal consistency and the appropriateness of the observed items in representing their respective theoretical constructs. These results support the model’s overall reliability and validity.

Convergent validity, which assesses the correlation between the construct variables. A loading above 0.7 is typically indicative of a strong relationship between the observable variables that contribute to the formation of the construct. However, the Service Innovation construct showed a factor loading of 0.614, falling short of the recommended benchmark. This is not a situation that restricts or invalidates the search results; however, it suggests that either item refinement or adding new variables may be necessary to measure the construct better.

Despite this, the correlations between Service Innovation and Environmental Practices (0.744), as well as between Service Innovation and Sustainable Competitive Advantage (0.820), exceeded 0.7, suggesting strong associations among these constructs.

Discriminant validity was evaluated to determine whether constructs were distinct. The correlation between Service Innovation and Environmental Practices (0.626) was relatively high, indicating potential conceptual overlap. A similar issue was observed between Service Innovation and Sustainable Competitive Advantage (0.700). The correlation between Environmental Practices and Sustainable Competitive Advantage (0.680) was slightly lower but still notable.

While the strong inter-construct correlations indicate good integration, the high correlation involving Service Innovation suggests that the conceptual boundaries among these constructs may need clarification, although the concepts expressed in the observable variables of each construct are theoretically distinct. These results do not invalidate the proposed model; however, for future research, it is suggested to improve the distinction of each construct to strengthen the discriminant validity and improve the overall effectiveness of the model, as outlined in Table 1.

Table 1.

Convergent Validity and Discriminant Validity.

Table 1.

Convergent Validity and Discriminant Validity.

| Service Innovation | Environmental Practices | Sustainable Competitive Advantage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Service Innovation | 0.614 | ||

| Environmental Practices | 0.626 | 0.744 | |

| Sustainable Competitive Advantage | 0.700 | 0.680 | 0.820 |

A correlation analysis was conducted using Pearson’s coefficient, which indicated the potential presence of multicollinearity among several variables. The highest observed correlations were between: EP2 ⟷ EP4 = 0.760; EP2 ⟷ EP5 = 0.811; EP3 ⟷ EP4 = 0.710; EP4 ⟷ EP5 = 0.742; SCA2 ⟷ SCA3 = 0.790; SCA2 ⟷ SCA4 = 0.793; SCA3 ⟷ SCA4 = 0.862.

These correlations indicate a strong association among the variables, suggesting they share similar behaviors. The high degree of correlation between certain variables may point to redundancy in the measurement of related constructs, which can affect the accuracy and stability of analytical models (Hair et al., 2014).

To further investigate the structure of each factor, intra-block Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was performed. This analysis focused on assessing the internal cohesion of each individual factor by evaluating key indicators, including Communality, Factor Loadings, Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure, Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity, Explained Variance, and Cronbach’s Alpha. These metrics were applied to the three factors identified in the Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA): (i) Factor 1—Service Innovation, (ii) Factor 2—Environmental Practices, and (iii) Factor 3—Sustainable Competitive Advantage. Table 2 presents the analysis of the Service Innovation construct, offering a detailed examination of the relevant indicators. This evaluation enables an assessment of the internal consistency of each factor and ensures that the constructs are clearly defined and appropriately represented by the indicators used in the study.

Table 2.

Intra-block factor analysis—Service Innovation construct.

Table 2.

Intra-block factor analysis—Service Innovation construct.

| Observable Variables | Factor Loading | Communality | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SIN1 | I tend to value hotel companies that innovate their services with technical features and functionalities that differ from existing offerings. | 0.780 | 0.437 |

| SIN2 | I always look for or take notice when a hotel company has developed or adopted a noteworthy Service Innovation. | 0.688 | 0.792 |

| SIN3 | I believe Service Innovation is aligned with Environmental Practices. | 0.595 | 0.674 |

| SIN4 | I associate Service Innovation with the implementation of new technologies. | 0.583 | 0.805 |

| SIN5 | In general, I tend to value hotel companies that innovate in their service offerings. | 0.817 | 0.777 |

| KMO 0.825 | 0.825 | ||

| Barlett’s Sphericity Test (Significance level p < 0.001) | 440.105 | ||

| Variance Explained | 58.74% | ||

| Cronbach’s Alpha | 0.817 | ||

| Composite Reliability | 0.886 | ||

The intra-block analysis for the Service Innovation construct (Table 3) shows that all indicators meet the criteria suggested by the reference authors. The factor loadings exceed the 0.5 threshold, with the variable SIN5 showing the highest loading (0.830), indicating the significance of actions taken in response to market demands and innovation trends. Cronbach’s Alpha exceeds 0.7, indicating strong internal consistency of the data. The communalities of the variables are all above 0.5, and the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) index falls between 0.8 and 0.9, both of which are favorable for factor analysis. Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity is significant (p < 0.001), further validating the construct’s structure.

For the Environmental Practices construct, the factor loadings are also greater than 0.5. However, the EP1 variable has a communality below 0.5, suggesting that it may not adequately explain the variance within the construct. Nonetheless, other indices, such as Cronbach’s Alpha, KMO, and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity, show satisfactory values, indicating acceptable internal consistency for the Environmental Practices construct.

Table 3.

Intra-block factor analysis—environmental practices construct.

Table 3.

Intra-block factor analysis—environmental practices construct.

| Observable Variables | Factor Loading | Communality | |

|---|---|---|---|

| EP1 | I consciously engage in environmentally responsible behaviors during my hotel stays by minimizing water and energy use, reducing waste, and conserving resources | 0.545 | 0.653 |

| EP2 | I appreciate and prefer hotel companies that implement Environmental Practices. | 0.889 | 0.605 |

| EP3 | I tend to favor hotels that use eco-labeled products and adopt practices such as reusing sheets and towels. | 0.737 | 0.494 |

| EP4 | I value hotel companies that incorporate recyclable and biodegradable materials in their operations. | 0.868 | 0.497 |

| EP5 | I support hotel companies that implement Environmental Practices aimed at enhancing the quality of life for individuals and communities. | 0.876 | 0989 |

| KMO | 0.849 | ||

| Barlett’s Sphericity Test (Significance level p < 0.001) | 807.139 | ||

| Variance Explained | 69.71% | ||

| Cronbach’s Alpha | 0.880 | ||

| Composite Reliability | 0.934 | ||

The intra-block analysis for the Sustainable Competitive Advantage construct (Table 4) demonstrates adequacy across all the indicators analyzed. The factor loadings exceed the 0.5 threshold, in line with the recommendations of Hair et al. (2014), underscoring the robustness of the identified factors. The variable SCA4, which addresses the preference for hotel companies prioritizing innovation and sustainability, exhibits the highest factor loading (0.931), emphasizing the strategic importance of these practices for gaining a competitive advantage. Cronbach’s Alpha exceeds 0.7, indicating strong internal consistency. The communalities of the variables are above 0.5, and the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) index is within satisfactory levels, as suggested by Pestana and Gageiro (2005). Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity is significant, confirming the multidimensional structure of the construct.

After validating the individual scales and conducting intra-block analyses to ensure the consistency of the constructs, the research moved on to the analysis of the integrated theoretical model, which connects the structural measurement models. The aim was to explore the interrelationships between the constructs of Market Orientation, Product Innovation, Process Innovation, and Organizational Performance. The analysis focused on evaluating the relationships between the observed variables of each construct, providing deeper insights into the phenomenon studied and shedding light on strategic orientation aspects such as Service Innovation, Environmental Practices, and Sustainable Competitive Advantage.

Table 4.

Intra-block factor analysis—Sustainable Competitive Advantage construct.

Table 4.

Intra-block factor analysis—Sustainable Competitive Advantage construct.

| Observable Variables | Factor Loading | Communality | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SCA1 | I recognize and value hospitality companies that have the necessary resources to implement strategies that enhance sustainability, efficiency, and effectiveness. | 0.645 | 0.584 |

| SCA2 | I choose hotel companies that publicly report on their sustainability performance. | 0.856 | 0.814 |

| SCA3 | I prefer to stay with hotel companies that adopt cleaner technologies to conserve resources and prevent pollution (such as energy, water, and waste). | 0.922 | 0.853 |

| SCA4 | I choose hotel companies where innovation and sustainability are core priorities in their service offerings. | 0.933 | 0.867 |

| KMO | 0.826 | ||

| Barlett’s Sphericity Test (Significance level p < 0.001) | 768.341 | ||

| Variance Explained | 77.96% | ||

| Cronbach’s Alpha | 0.905 | ||

| Composite Reliability | 0.946 | ||

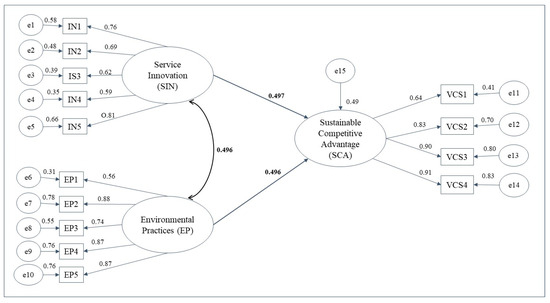

The research framework was operationalized using all observable variables, with data processing and analysis conducted through AMOS (version 24.0) and SPSS Statistics (version 26). Figure 2 illustrates the components of both the measurement and structural models. The measurement model includes the observable variables that comprise each construct, such as Service Innovation (SIN), Environmental Practices (EP), and Sustainable Competitive Advantage (SCA).

Figure 2.

Final integrated model.

The output data from the AMOS software report, used to analyze the absolute fit measures, are presented in Table 5. The fit indices, based on the studies by Hair et al. (2014), confirm that the model is appropriate for the study data, according to the fit criteria recommended by various authors. The ratio between the chi-square (χ2 = 353.846) divided by the degrees of freedom (DF = 75) resulted in a value of 4.718, close to the ideal limit of 5. The root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) was 0.120, slightly exceeding the recommended range of 0.05-0.08. However, the IFI (0.886), TLI (0.861), and CFI (0.885) indices fell within the acceptable range. Although the model is generally suitable, improvements can be made, as some indices indicated suboptimal values. These include the Normalized Fit Index (NFI = 0.860), the Global Fit Index (GFI = 0.841), and the Adjusted Global Fit Index (AGFI = 0.777). The Expected Cross-Validation Index (ECVI) was 1.59. The results of the model fit indices (RMSEA, IFI, TLI, CFI, NFI, GFI, AGFI) were close to, but did not reach, the recommended parameters. These results do not invalidate the research, but suggest that new research may involve other constructs and new observable variables, as those used in the research reflect a theoretical model that still needs improvements in future research.

Table 5.

Fit indices of the integrated model.

The interdependencies between the variables were analyzed using correlation and covariance tests. The study’s hypotheses were confirmed, as all associations yielded positive and statistically significant results (Table 6). In addition, the Critical Ratio (CR) index was satisfactory, with values exceeding |1.59|, indicating that the estimates are statistically different from zero, as recommended by Byrne (2013).

Table 6.

Hypothesis test (correlation and covariance)—theoretical integrated model.

The results presented in Table 6, which correspond to the hypothesis tests with correlation and covariance in the final integrated model, confirm the validity of all the hypotheses tested:

- (a)

- Hypothesis 1 (H1): Service Innovations (SIN) have a significant positive influence on Sustainable Competitive Advantage (SCA) in lodging establishments. The Estimated Coefficient (EC) was 0.398, with a Standardized Coefficient (SC) of 0.497 and a Critical Ratio (CR) of 7.055 (p < 0.001). The positive relationship between SIN and SCA is supported by the literature, which highlights the importance of innovation as a strategy for differentiation and sustainable competitiveness.

- (b)

- Hypothesis 2 (H2): Environmental Practices (EP) have a significant positive influence on Sustainable Competitive Advantage (SCA). The EC was 0.417, with SC of 0.496 and CR of 7.467 (p < 0.001), indicating a strong relationship between EP and SCA. The literature supports the notion that sustainable Environmental Practices not only enhance corporate image but also attract consumers who are concerned about sustainability.

- (c)

- Hypothesis 3 (H3): There is a significant correlation between Service Innovations (SIN) and Environmental Practices (EP) in lodging establishments. The EC was 0.556, SC 0.496, and CR 7.340 (p < 0.001), confirming a positive association between SIN and EP. This finding highlights the importance of an integrated approach to strategic management, where the combination of innovation and Environmental Practices creates synergies, contributing to a robust and sustainable competitive advantage.

Following the statistical analysis of the structural model and based on the results and tests, the research hypotheses were supported, as shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

Research hypotheses.

5. Discussions

Based on the research results, presented in Table 7, regarding the hypothesis testing using correlation and covariance in the final integrated model, the following research findings were observed:

- (a)

- Hypothesis 1 (H1): Service innovation (SI) exerts a significant positive influence on sustainable competitive advantage (SCA) in lodging establishments. The positive relationship between service innovation and sustainable competitive advantage is supported by (Fraj et al., 2015; De Guimarães et al., 2016; López-Gamero et al., 2023b), which highlight the importance of differentiation and innovation as key strategies for standing out in competitive markets. Service innovation not only attracts customers by offering unique and personalized experiences, but can also reduce operating costs and increase efficiency, thus contributing to sustainable competitive advantage (Lopes & Basso, 2023; López-Gamero et al., 2023a; De Guimarães et al., 2016; Putra & Putri, 2019);

- (b)

- Hypothesis 2 (H2): Environmental practices (EPs) have a significant positive influence on sustainable competitive advantage (SCA) in lodging establishments. Environmental practices as determinants of sustainable competitive advantage are widely supported by studies highlighting the economic and reputational benefits of operating in an environmentally responsible manner (Severo & De Guimarães, 2022; Gössling et al., 2021; Molina-Collado et al., 2022; López-Gamero et al., 2023b). Companies that adopt environmental practices not only respond to regulatory and social expectations but also improve their corporate image and attract consumers who value sustainability (Severo et al., 2020; López-Gamero et al., 2023b);

- (c)

- Hypothesis 3 (H3): There is a significant correlation between service innovation (SI) and environmental practices (EPs) in lodging establishments. This confirms a positive association between SI and PA. Furthermore, the positive correlation between service innovation and environmental practices found in the study highlights the importance of an integrated approach to the strategic management of lodging establishments. Combining different resources and capabilities can generate synergies that cannot be achieved in isolation, enabling a more robust and sustainable competitive advantage (Chen & Tung, 2014; Latif et al., 2020; Severo et al., 2019; De Guimarães et al., 2021; López-Gamero et al., 2023b).

Therefore, the research results validated all the hypotheses tested, demonstrating that both service innovation and environmental practices are significant factors that positively contribute to sustainable competitive advantage in lodging establishments. Furthermore, the correlation between these constructs highlights the importance of integrated strategies that promote both innovation and environmental sustainability as key elements for organizational success in the lodging sector.

6. Conclusions

This research explored the intersections among Service Innovation, Environmental Practices, and Sustainable Competitive Advantage in the lodging sector. It is based on theories of competitive advantage, strategic resources, and innovation. In this sense, the study aims to understand how these practices can be strategic resources for lodging companies in competitive markets.

The primary objective was to analyze the relationship between Service Innovation and Environmental Practices and their combined contribution to Sustainable Competitive Advantage. By offering unique solutions tailored to consumer needs, Service Innovation helps companies differentiate themselves and create entry barriers for potential competitors. In addition, Environmental Practices such as energy efficiency and waste management can reduce operational costs, enhance brand reputation, and appeal to sustainability-conscious consumers and investors. The research also assessed how these practices influence both the tangible dimensions (e.g., cost savings) and intangible elements (e.g., customer loyalty and corporate image) of Sustainable Competitive Advantage.

An essential academic contribution of this research is the development of a conceptual framework to analyze the antecedents of Sustainable Competitive Advantage. This framework advances organizational theory and offers practical application through the perspective of service users. Moreover, the study provides an analytical instrument for examining the interaction between Service Innovation and Environmental Practices within the lodging industry.

The findings confirm the strategic importance of investing in both service innovation and environmental management as pathways to achieving Sustainable Competitive Advantage. In addition to confirming theoretical relationships, the research offers a set of Environmental Practices that can be adapted to diverse business contexts, enabling lodging companies to respond effectively to growing market demands for sustainability and social responsibility.

Based on the research results, it is suggested that hotels develop sustainable practices such as waste segregation, reuse of materials, reduction of water and energy consumption, and a campaign to encourage guests to avoid high costs, energy, and inputs in cleaning the environment and materials used, such as towels. In this aspect, guest involvement and participation are fundamental to the success of environmental actions, to generating a competitive advantage.

Key drivers of Sustainable Competitive Advantage in lodging establishments emerged from the analysis. As a practical contribution, the study provides guidance for managers and decision-makers seeking to reassess and refine their strategies, emphasizing those initiatives that enhance the customer experience. By aligning Service Innovation with Environmental Practices, organizations not only strengthen their competitive market position but also fulfill increasing societal expectations for sustainability and ethical business conduct, promoting a management approach that reflects contemporary values of environmental responsibility and service excellence.

Innovation is widely recognized as a critical source of competitive advantage for companies (Porter, 2008; De Guimarães et al., 2016). Both authors emphasize that organizations must continually seek new ways to create value for customers, whether through innovative products or distinctive services. Differentiation through innovation enables companies to establish a unique market position, making it challenging for competitors to replicate their offerings.

Among the limitations of the research is the potential for Common Method Variance (CMV) and the Halo effect (generalization bias), as data were collected via a five-point Likert scale and responses were obtained from a single respondent (Bagozzi & Yi, 1991; Podsakoff et al., 2003). Another limitation of the research is the use of the Snowball data collection technique, which could potentially introduce a bias towards the homogeneity of the respondents. In this sense, it is suggested that probabilistic samples can be used in future research. The research applied various statistical tests to assess and mitigate such biases, including the Kurtosis Index, Pearson’s Skewness Coefficient, Cronbach’s Alpha, KMO, Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity, Composite Reliability, and CFA. These evaluations revealed no significant evidence of bias in the data.

The results also highlight opportunities for future research. Key questions include: How are Service Innovation and Environmental Practices managed by companies that consistently achieve superior Sustainable Competitive Advantage? What are the relationships between Service Innovation and Environmental Practices in generating Sustainable Competitive Advantage in different tourism service companies? While the use of innovation and environmental strategies is evident, further research is needed to identify the specific organizational processes that are predictors of these constructs, enhancing their impact and contributing to improved business performance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization S.d.S.G., J.C.F.d.G., C.S.B.; Methodology S.d.S.G., J.C.F.d.G.; Validation S.d.S.G., J.C.F.d.G., J.R.R.S., C.S.B., V.A.G.T.; Formal analysis S.d.S.G., J.C.F.d.G., J.R.R.S., V.A.G.T.; Investigation S.d.S.G., J.C.F.d.G.; Resources S.d.S.G., J.C.F.d.G., J.R.R.S., C.S.B., V.A.G.T.; Original Draft S.d.S.G., J.C.F.d.G., J.R.R.S., C.S.B., V.A.G.T., V.S.S.; Data Curation S.d.S.G.; Writing—Review & Editing S.d.S.G., J.C.F.d.G., J.R.R.S., C.S.B., V.A.G.T., V.S.S.; Project administration S.d.S.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because this is not research involving the physical or psychological manipulation of human beings; in Brazil it is not considered necessary for research to go through an Ethics Committee (LAW Nº 14.874, OF MAY 28, 2024). In Brazil, only health-related research involving the manipulation of human beings and animals goes through an Ethics Committee. https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2023-2026/2024/lei/l14874.htm (accessed on 10 November 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The research was carried out with support received from the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq), Brazil.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, F., Rasoolimanesh, S. M., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., & Ryu, K. (2018). An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) in hospitality research. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 30(1), 514–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alreahi, S. (2023). The intersection of service innovation and environmental practices in the hospitality industry: A review of literature and trends. Tourism Management, 84, 315–328. [Google Scholar]

- Babiak, K., & Trendafilova, S. (2011). CSR and environmental responsibility: Motives and pressures to adopt green management practices. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 18(1), 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R. P., & Yi, Y. (1991). Multitrait-multimethod matrices in consumer research. Journal of Consumer Research, 17(4), 426–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural equations. Psychological Bulletin, 107(2), 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bentler, P. M., & Bonett, D. G. (1980). Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin, 88(3), 588–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollen, K. A. (1989). A new incremental fit index for general structural equation models. Sociological Methods and Research, 17(3), 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazil. (2024a). LAW Nº 14.874, of May 28. Available online: https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2023-2026/2024/lei/l14874.htm (accessed on 28 July 2024).

- Brazil. (2024b). Tendencia do turismo 2024, 5th ed.; Ministério do Turismo. Available online: https://www.gov.br/turismo/pt-br/acesso-a-informacao/acoes-e-programas/programas-projetos-acoes-obras-e-atividades/rede-inteligencia-mercado/revista-tendencias-2024-vfinal.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- Brazil. (2024c). ABNT NBR ISO 14001-2015 (2024c): Revises parts of the original document, leaving the remainder unchanged. This amendment introduces the consideration of ‘climate change’ in subsections 4.1 and 4.2, reflecting ISO’s climate action commitments. Available online: https://pt.scribd.com/document/872334775/0-02-ABNT-NBR-ISO-14001-2015-Ambiental-Emenda-1-2024 (accessed on 5 August 2024).

- Byrne, B. M. (2013). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E. S. (2013). Managing green marketing: Hong Kong hotel managers’ perspective. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 34, 442–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M. F., & Tung, P. J. (2014). The moderating effect of green perceived value on green satisfaction and green loyalty. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 36, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y. H., Chang, K. C., Cheng, Y. S., & Hsiao, C. J. (2022). How green marketing influences customers’ green behavioral intentions in the context of hot-spring hotels. Journal of Tourism and Services, 13(24), 190–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damanpour, F. (1991). Organizational innovation: A meta-analysis of effects of determinants and moderators. Academy of Management Journal, 34(3), 555–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Guimarães, J. C. F., Dorion, E. C. H., & Severo, E. A. (2020). Antecedents, mediators and consequences of sustainable operations: A framework for analysis of the manufacturing industry. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 27(7), 2189–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Guimarães, J. C. F., Severo, E. A., Dorion, E. C. H., Coallier, F., & Olea, P. M. (2016). The use of organizational resources for product innovation and organizational performance: A survey of the brazilian furniture industry. International Journal of Production Economics, 180, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Guimarães, J. C. F., Severo, E. A., Jabbour, C. J. C., De Sousa Jabbour, A. B. L., & Rosa, A. F. P. (2021). The journey towards sustainable product development: Why are some manufacturing companies better than others at product innovation? Technovation, 103, 102239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Guimarães, J. C. F., Severo, E. A., Klein, L. L., Dorion, E. C. H., & Lazzari, F. (2023). Antecedents of sustainable consumption of remanufactured products: A circular economy experiment in the Brazilian context. Journal of Cleaner Production, 385, 135571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Den Hertog, P., Van der Aa, W., & De Jong, M. W. (2010). Capabilities for managing service innovation: Towards a conceptual framework. Journal of Service Management, 21(4), 490–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzhangzhugazova, E. A., Blinova, E. A., Orlova, L. N., & Romanova, M. M. (2016). Innovations in the hospitality industry. International Journal of Environmental and Science Education, 11(17), 10387–10400. [Google Scholar]

- Erdogan, N., & Baris, E. (2007). Environmental protection programs and conservation practices of hotels in Ankara, Turkey. Tourism Management, 28(2), 604–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. (2018). The measurement of scientific, technological and innovation activities oslo manual 2018 guidelines for collecting, reporting and using data on innovation. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatoki, O. (2021). Environmental orientation and green competitive advantage of hospitality firms in South Africa: Mediating effect of green innovation. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 7(4), 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 17(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraj, E., Matute, J., & Melero, I. (2015). Environmental strategies and organizational competitiveness in the hotel industry: The role of learning and innovation as determinants of environmental success. Tourism Management, 46, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallouj, F., Djellal, F., & Gallouj, C. (2023). Advanced introduction to service innovation. Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Gebauer, H., Gustafsson, A., & Witell, L. (2010). Competitive advantage through service differentiation by manufacturing companies. Journal of Business Research, 63(12), 1279–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffin, K., & Mitchell, R. (2022). Innovation management: Strategy and implementation using the Pentathlon framework. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Gomezelj, D. O. (2016). A systematic review of research on innovation in hospitality and tourism. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 28(3), 516–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S., Scott, D., & Hall, C. M. (2021). Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(1), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Black, W. C., Bardin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2014). Multivariate data analysis: Pearson new international edition (7th ed.). Pearson Education Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Hameed, W. U., Nisar, Q. A., & Wu, H. C. (2021). Relationships between external knowledge, internal innovation, firms’ open innovation performance, service innovation and business performance in the Pakistani hotel industry. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 92, 102745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzallah, A. M., Iriqat, R. A., Hamed, M. H., Zaki, K., & Elnagar, A. K. (2025). Green synergy in hospitality: Unveiling the nexus between environmentally sustainable practices and hotel green performance. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 131, 104301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjalager, A. M. (2010). A review of innovation research in tourism. Tourism Management, 31(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M. S., Kannan, S. N., & Raman Nair, S. K. K. (2021). Factors influencing sustainable competitive advantage in the hospitality industry. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism, 22(6), 679–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, H., Albadry, O. M., Mathew, V., Al-Romeedy, B. S., Alsetoohy, O., Abou Kamar, M., & Khairy, H. A. (2024). Digital leadership and sustainable competitive advantage: Leveraging green absorptive capability and eco-innovation in tourism and hospitality businesses. Sustainability, 16(13), 5371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, A., Kale, S., Chandel, S., & Pal, D. K. (2015). Likert scale: Explored and explained. British Journal of Applied Science & Technology, 7(4), 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallmuenzer, A. (2018). Exploring drivers of innovation in hospitality family firms. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 30(3), 1978–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, L. L., De Guimarães, J. C. F., Severo, E. A., Dorion, E. C. H., & Schirmer Feltrin, T. (2023). Lean practices toward a balanced sustainability in higher education institutions: A Brazilian experience. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 24(2), 259–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. (2023). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Latif, K. F., Pérez, A., & Sahibzada, U. F. (2020). Corporate social responsibility (CSR) and customer loyalty in the hotel industry: A cross-country study. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 89, 102565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, Q., Hollenhorst, S., Harris, C., McLaughlin, W., & Shook, S. (2006). Environmental management: A study of Vietnamese hotels. Annals of Tourism Research, 33(2), 545–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S., Oh, H. Y., & Choi, J. (2021). Service design management and organizational innovation performance. Sustainability, 13(1), 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liasidou, S., & Pipyros, K. (2025). Introduction to the thematic issue: Transformative relationships between tourism and technology. Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes, 17(1), 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, J. L., & Basso, L. F. C. (2023). The impact of eco-innovation adoption on business Performance—A study of the hospitality sector in Brazil. Sustainability, 15(11), 8696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Gamero, M. D., Molina-Azorín, J. F., Pereira-Moliner, J., & Pertusa-Ortega, E. M. (2023a). Agility, innovation, environmental management and competitiveness in the hotel industry. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 30(2), 548–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Gamero, M. D., Pereira-Moliner, J., Molina-Azorín, J. F., Tarí, J. J., & Pertusa-Ortega, E. M. (2023b). Human resource management as an internal antecedent of environmental management: A joint analysis with competitive consequences in the hotel industry. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 31(6), 1293–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahran, K., Albarrak, H., Ibrahim, B. A., & Elamer, A. A. (2025). Leadership and sustainability in tourism and hospitality: A systematic review and future research agenda. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 37(7), 2219–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardia, K. V. (1971). The effect of nonnormality on some multivariate tests and robustness to nonnormality in the linear model. Biometrika, 58(1), 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marôco, J. (2010). Análise de equações estruturais: Fundamentos teóricos, software & aplicações. PSE. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, P., Pérez, A., & Rodríguez del Bosque, I. (2014). Exploring the role of CSR in the organizational identity of hospitality companies: A case from the Spanish tourism industry. Journal of Business Ethics, 124, 47–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, R. P., & Marsh, H. W. (1990). Choosing a multivariate model: Noncentrality and goodness of fit. Psychological Bulletin, 107, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensah, I., & Blankson, E. J. (2013). Determinants of hotels’ environmental performance: Evidence from the hotel industry in Accra, Ghana. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 21(8), 1212–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihalic, T. (2024). Trends in sustainable tourism paradigm: Resilience and adaptation. Sustainability, 16(17), 7838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Collado, A., Santos-Vijande, M. L., Gómez-Rico, M., & Madera, J. M. (2022). Sustainability in hospitality and tourism: A review of key research topics from 1994 to 2020. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 34(8), 3029–3064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambisan, S., Wright, M., & Feldman, M. (2019). The digital transformation of innovation and entrepreneurship: Progress, challenges and key themes. Research Policy, 48(8), 103773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagell, M., & Gobeli, D. (2009). How plant managers’ experiences and attitudes toward sustainability relate to operational performance. Production and Operations Management, 18(3), 278–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paget, E., Dimanche, F., & Mounet, J. P. (2010). A tourism innovation case: An actor-network approach. Annals of Tourism Research, 37(3), 828–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira-Moliner, J., López-Gamero, M. D., Font, X., Molina-Azorín, J. F., Tarí, J. J., & PertusaOrtega, E. M. (2021). Sustainability, competitive advantages and performance in the hotel industry: A synergistic relationship. Journal of Tourism and Services, 23(12), 132–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pestana, M. H., & Gageiro, J. N. (2005). Análise de dados para ciências sociais: A complementaridade do SPSS (4th ed.). Edições Sílabo. [Google Scholar]

- Pikkemaat, B. (2008). Innovation in small and medium-sized tourism enterprises in Tyrol, Austria. The International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation, 9(3), 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikkemaat, B., Peters, M., & Bichler, B. F. (2019). Innovation research in tourism: Research streams and actions for the future. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 41, 184–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., Mackenzie, S. B., Lee, J., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended Remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M. E. (2008). The five competitive forces that shape strategy. Harvard Business Review, 86(1), 78–93. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M. E., & Van der Linde, C. (1995). Toward a new conception of the environment-competitiveness relationship. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 9(4), 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putra, I. W. J. A., & Putri, D. P. (2019). The mediating role of relationship marketing between service quality and customer loyalty. Journal of Relationship Marketing, 18(3), 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjay, K., Tewari, S., & Subbarao, A. N. (2025). Bridging the attitude–behavior Gap in green marketing: A structural equation modeling approach to psychological and environmental influences. In S. Dua, S. Dua, & P. Kaur (Eds.), Green marketing perspectives (pp. 53–67). Emerald Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Severo, E. A., Becker, A., Guimarães, J. C. F. D., & Rotta, C. (2019). The teaching of innovation and environmental sustainability and its relationship with entrepreneurship in Southern Brazil. International Journal of Innovation and Learning, 25(1), 78–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severo, E. A., & De Guimarães, J. C. F. (2022). The influence of product innovation, environmental strategy and circular economy on sustainable development in organizations in Northeastern Brazil. Journal of Law and Sustainable Development, 10(2), e0223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severo, E. A., De Guimarães, J. C. F., & Dellarmelin, M. L. (2020). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on environmental awareness, sustainable consumption and social responsibility: Evidence from generations in Brazil and Portugal. Journal of Cleaner Production, 286, 124947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Severo, E. A., De Guimarães, J. C. F., & Dorion, E. C. H. (2018). Cleaner production, social responsibility and eco-innovation: Generations’ perception for a sustainable future. Journal of Cleaner Production, 186, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S., & Vredenburg, H. (1998). Proactive corporate environmental strategy and the development of competitive advantage. Strategic Management Journal, 19(8), 729–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava, P. (1995). The role of corporations in achieving ecological sustainability. Academy of Management Review, 20(4), 936–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H., Li, S., Wen, T., & Liang, Y. (2025). The impact of industry network strength, centrality and heterogeneity on entrepreneurial performance in the hospitality and tourism: Perspectives on innovation and leadership. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 127, 104088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri, B., Kromidha, E., Prayag, G., & Gannon, M. (2025). Do ethics, locavorism, and engagement stimulate memorable wine tourism and hospitality experiences? A moral identity perspective. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 131, 104323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajeddini, K., Gamage, T. C., Tajdini, J., Hameed, W. U., & Tajeddini, O. (2024). Exploring the effects of service innovation ambidexterity on service design in the tourism and hospitality industry. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 119, 103730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajeddini, K., & Trueman, M. (2012). Managing Swiss Hospitality: How cultural antecedents of innovation and customer-oriented value systems can influence performance in the hotel industry. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 31(4), 1119–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, J. S., & Huba, G. J. (1985). A fit index for covariance structure models under arbitrary GLS estimation. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 38, 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D. J. (2018). Dynamic capabilities as (workable) management systems theory. Journal of Management & Organization, 24(3), 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wernerfelt, B. (1984). A resource-based view of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 5(2), 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiśniewska, A., Liczmańska-Kopcewicz, K., & Żemigała, M. (2025). Cognitive and affective antecedents of consumer engagement in green innovation processes. Sustainable Futures, 9, 100750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witell, L., Snyder, H., Gustafsson, A., Fombelle, P., & Kristensson, P. (2016). Defining service innovation: A review and synthesis. Journal of Business Research, 69(8), 2863–2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. (2023). CO2 emissions—Brazil (2023 update). World Bank Open Knowledge Repository. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/home (accessed on 5 November 2024).