1. Introduction

Emerging in a foreign market is a complex decision, often hindered by a lack of preparation, insufficient market knowledge, or the strategic difficulty of selecting the appropriate country in which to internationalize (

Anderson, 2011). However, it is also within international and tourism-driven markets that many opportunities arise, offering access to new consumers, diversified resources, and greater economic resilience (

Ashley et al., 2007). In this context, internationalization emerges not only as a response to market saturation but also as a strategic path to reinforcing the image of national identity abroad.

The Portuguese textile industry, traditionally recognized for its high quality, has gained increasing international recognition, being sought after not only by countries within the European Union but also beyond, including emerging markets such as China (

Serra et al., 2012). China stands out as one of the world’s major economic powers, being the third-largest country by area and home to one fifth of the world’s population. Since the implementation of its economic reforms, it has become one of the fastest-growing economies globally, the largest exporter, and the third-largest importer of goods.

While China represents a market of great potential, it simultaneously poses significant challenges. Its cultural, political, and commercial specificities demand careful strategic adaptation by foreign firms (

Hofstede, 2022;

Falardo & Sequeira, 2021). Although the textile sector is among the most important ones for Portugal, representing over 8% of national exports in some years (

Banco de Portugal, 2022), its visibility and brand equity in distant and complex markets like China remain underexplored (

AICEP, 2022a).

Despite the relevance of the topic, the academic literature on the internationalization of Portuguese textile companies in China is extremely limited. The few existing studies are mostly case-based and offer fragmented perspectives (

Dias, 2021), failing to provide a structured understanding of the critical factors that lead to business success in this context. Furthermore, there is a scarcity of theoretical, critical, and empirical reflection in Portugal that explores the intersection between international business dynamics and their contribution to the destination image and tourist consumer behavior.

This study seeks to address this gap by investigating the key factors that contribute to the internationalization of Portuguese textile companies into the Chinese market and by examining the extent to which this international presence reinforces Portugal’s image as a destination. Adopting a qualitative and inductive methodological approach, this research also explores how international business strategies may intersect with national branding processes.

Accordingly, the following research questions guide the investigation:

RQ1. What characterizes the internationalization strategies of Portuguese textile companies already operating in China?

RQ2. How are companies preparing to enter the Chinese market in the near future?

RQ3. What are the common patterns—strategic, cultural, technological or communicational—across both groups that may contribute to the construction of Portugal’s destination image abroad?

2. Theoretical Background

The process of internationalization has long shaped global commerce, evolving from early mercantile expansion to contemporary strategic globalization. In recent decades, the phenomenon has intensified as companies seek to diversify risk, access new consumer bases, and enhance their competitive advantages (

Kotler & Keller, 2019;

Bartlett & Beamish, 2018). The textile industry in particular has been profoundly affected by these dynamics, with product quality, branding, and cultural resonance becoming core differentiators in global markets.

This literature review synthesizes key conceptual domains that underpin this study: (1) internationalization strategies, (2) the relationship between international marketing and destination image, (3) cultural dimensions and tourism, (4) internationalization models, and (5) contextual specificities of the Chinese market. Each domain is supported by relevant authors, as presented in

Table 1.

Despite the breadth of the existing literature, few studies have explored the intersection between industry-led internationalization and destination image construction, particularly in the context of emerging markets like China. There is also a lack of empirical research on how national industries, especially in product-based sectors such as textiles, can contribute to shaping the perception of a country abroad through their presence in foreign markets.

Internationalization was already considered fundamental in Phoenician and Carthaginian society. However, the phenomenon intensified in the late 15th and 18th centuries with the mercantilist doctrine, which boosted international trade and reached its peak after the discovery of America and the sea route to India (

Costa e Silva et al., 2018).

Kotler and Keller (

2019) stated that it has shortened borders, and consequently, cultures are increasingly close and dependent on each other. But even so, most companies would choose to remain in the domestic market if it were sufficient, as it would be easier and less expensive. Nevertheless, emerging in a foreign market can create a number of opportunities. According to

Bartlett and Beamish (

2018), carrying out operations all over the world not only provides access to new markets and more economical resources but also offers new sources of information and knowledge which, consequently, will make the company expand its strategies to compete in both the domestic and foreign markets. With the growing demand for the international market, especially from developed countries, companies have begun to find business opportunities in emerging economies (

London & Hart, 2004), i.e., countries that are experiencing faster economic growth, such as South Korea, Singapore, Taiwan, Brazil, India, Mexico, Argentina, Indonesia, Russia, Thailand, China, and Poland (

Ferreira et al., 2011).

2.1. International Marketing and Destination Image

When internationalization is mentioned, the need to link (tourism) marketing to it inevitably arises, since companies will have to adapt and adjust their products or services to the country they want to enter (

Luong, 2025). At the root of these strategies are two particularly important factors: local adaptation and pressure on costs. In other words, when the pressure for local adaptation is stronger, the company seeks to adapt its offer to the countries where it is going to emerge (

Ferreira et al., 2011). According to

Ferreira et al. (

2011), adaptation can come from various sources, such as consumer preferences and tastes, government requirements, and the specificities of each market. On the other hand, when the pressure on costs is higher, companies need to be more efficient by rationalizing their production and may choose locations where the cost of production is lower (

Hätönen, 2009). Of course, this type of pressure only works for products that can be mass produced and do not require differentiation. Thus, internationalization can be seen as a multidimensional decision problem that requires a set of choices, and although several studies have been carried out over the years, it is still unclear which factors and strategies are decisive for success (

Kraus et al., 2017). According to

Kotler and Keller (

2019), the internationalization process has four stages: the first stage, inconsistent export activities; the second stage, export through agents; the third stage, establishment of sales subsidiaries; and the fourth stage, establishment of industrial facilities abroad.

The relationship between international marketing and destination image is pivotal in the tourism industry (

Akroush et al., 2016;

Roman et al., 2022). International marketing strategies aim to promote destinations to a global audience, creating a compelling image that attracts tourists (

Hays et al., 2013). Destination image encompasses the perceptions and beliefs that potential visitors hold about a place, influenced by marketing efforts, media, and personal experiences (

Ye & Tussyadiah, 2011). Effective international marketing can enhance a destination’s image by highlighting its unique attributes, cultural heritage, and attractions, thereby differentiating it from competitors (

McCartney, 2008). This process involves strategic branding, advertising, and public relations campaigns designed to shape and maintain a positive destination image in the minds of international tourists. Moreover, the destination image significantly impacts tourists’ decision-making processes. A strong, positive image can increase a destination’s appeal, leading to higher visitation rates and economic benefits (

Al-Kwifi, 2015). International marketing plays a crucial role in managing and improving this image by continuously engaging with target audiences through various channels, including social media, travel blogs, and international travel fairs (

Kiráľová & Pavlíčeka, 2015). By understanding and leveraging the factors that contribute to the destination image, marketers can develop more effective campaigns that resonate with potential tourists, fostering loyalty and repeat visits (

Goeltom & Hurriyati, 2024). Thus, the synergy between international marketing and destination image is essential for the sustainable growth and success of tourism destinations (

Roman et al., 2020,

2024).

2.2. Culture and Tourism in the Internationalization Process

According to

Hofstede (

2022), deciding which country to export to on the basis of proximity and similarity is not always the most appropriate approach, as the six dimensions of culture must be taken into account: power distance, individualism, masculinity, aversion to uncertainty, long-term orientation (Confucian dynamism), and indulgence. Power distance reflects the degree of deference that individuals project toward their hierarchical superiors, i.e., the need to maintain and respect the relationship between a leader and their subordinates. Individualism argues that individuals should take care of themselves and be independent of groups or organizations. Masculinity refers to a society that focuses on competition and trying to achieve success. Uncertainty aversion shows how a society deals with ambiguous situations. Long-term orientation describes how societies must maintain links with the past in order to deal with the present and the future. Finally, indulgence is defined as the extent to which people try to control their desires and impulses, based on the way they were brought up. Culture and tourism play a pivotal role in the internationalization processes of companies by facilitating market entry and enhancing brand recognition. When companies expand into foreign markets, understanding and integrating local cultural nuances can significantly improve their acceptance and success. Tourism, on the other hand, serves as a powerful tool for promoting cultural exchange and awareness, allowing companies to showcase their products and services to a diverse audience. This exposure not only helps in building a positive brand image but also fosters trust and loyalty among international consumers. Consequently, leveraging culture and tourism can provide companies with a competitive edge, enabling them to navigate the complexities of global markets more effectively.

2.3. Models and Theories of Internationalization

The theories are divided into two distinct approaches: the economic approach and the behavioral approach. In the economic approach, the focus is on multinational companies based on economic return, since they have access to information and resources that allow them to make a more rational decision; in other words, the company decides to internationalize only if it brings benefits to itself and conducts a thorough internal and external analysis to make any decision. The behavioral approach focuses on the recent phenomenon involving small- and medium-sized enterprises and is based on the importance of organizational learning, while explaining internationalization as a gradual process (

Wu, 2020). The theories and models that will serve as examples for the process of entry into the international market by multinational companies and small- and medium-sized enterprises are the eclectic paradigm, the Uppsala model, network theory, and finally the theory of competitive advantages, since these are some of the most relevant and appropriate internationalization theories for this research work.

The eclectic paradigm, also known as ownership, location, internalization (OLI), was first presented in 1976 by the English economist John Dunning and has been refined over the years by other authors (

Dunning, 2001). However, despite being more than four decades old, it is considered one of the most influential frameworks for research related to foreign direct investment. Ownership advantages are all the tangible or intangible resources that a company has and its competitors do not, therefore providing it with a competitive advantage. The Uppsala model focuses on describing the internationalization process through a behavioral approach and is based on empirical studies that analyze the fact that Swedish companies develop their international operations in small steps, rather than making large investments all at once (

Johanson & Vahlne, 1977). Therefore, according to the aforementioned authors, internationalization is a gradual process in which companies acquire knowledge through experience in foreign markets, and this can influence their performance. Over time, companies increase their involvement in foreign markets through various stages.

Costa e Silva et al. (

2018) stated that involvement abroad is initially carried out through casual export activities, and then exporting begins using independent intermediaries located in the destination country and tourist destination. Network theory is seen as an extension of the Uppsala model, since several authors argue that this model can only be used in the first phase, where companies do not have sufficient knowledge of the market. On the other hand, this theory can not only help companies in the first phase but also support those that already have a certain amount of experience in internationalization (

Andersson, 2004). In this way, the internationalization process can be influenced not only by the conditions of the company itself but also by the relationships it develops in the foreign market.

Network theory is seen as an extension of the Uppsala model, since several authors argue that this model can only be used in the first phase, where companies do not have sufficient knowledge of the market. On the other hand, this theory can not only help companies in the first phase but also support those that already have a certain amount of experience in internationalization (

Andersson, 2004). In this way, the internationalization process can be influenced not only by the conditions of the company itself but also by the relationships it develops in foreign markets.

Also known as Porter’s Diamond, this theory argues that a country’s competitiveness can be measured when it is still operating only domestically, i.e., a country subject to internal rivalry becomes more sophisticated and more competent to face the international market (

Ferreira et al., 2011). According to the aforementioned authors, this theory helps understand where a company’s future competition may come from, since competitors will probably emerge from countries that offer companies location advantages.

Thus, the diamond model emphasizes some important factors for competitiveness, such as critical production factors, more important markets, more demanding customers, more sophisticated competition, and more developed suppliers.

2.4. Characterization of the Textile Sector in Portugal

According to the General Directorate of Economic Activities (2020), the textile sector is not only one of Portugal’s oldest and most traditional industries but also one of the country’s largest and most important business sectors. According to data released by the Bank of Portugal (

Banco de Portugal, 2022) in an analysis of the Textile and Clothing Industry in Portugal, the number of companies remained stable between 2015 and 2018. However, it has fallen sharply in recent years, particularly since 2019, from 6662 companies to 6346 in 2021. Despite everything, turnover has always seen gradual increases over the years, but this changed from a figure of EUR 7628.7 million in 2019 to EUR 6888 million in 2020. However, the sector showed a rapid recovery, rising to EUR 7975.5 million in 2021, already surpassing the figures recorded before the pandemic caused by COVID-19. According to the Bank of Portugal, the majority of companies in this sector are micro companies (60.7%), followed by small companies (30.4%), medium-sized companies (8.2%) and large companies (0.7%). However, turnover and the number of people employed stand out among medium-sized companies (49.5% and 43.2%, respectively). Regarding the export performance of the Portuguese textile sector, according to data provided by

AICEP (

2022b), the clothing industry accounted for 5.2% of exports in 2019, dropping to 4.8% in 2020. In contrast, the textile materials industry showed export growth, increasing from 3.5% in 2019 to 3.8% in 2020. With regard to exports from the Portuguese textile sector, according to data provided by

AICEP (

2022a), the clothing industry accounted for 5.2% of exports in 2019 and dropped to 4.8% in 2020. The textile materials industry, on the other hand, showed an increase in exports, from 3.5% in 2019 to 3.8% in 2020.

2.5. Specificities of the Chinese Market

China is a large nation with an ancient culture and enormous historical importance, and it is currently seen as one of the world’s greatest powers. It is the third-largest country in the world and has roughly one fifth of the world’s population (

Haw, 2005). According to data provided by

AICEP (

2022b), China has the second-largest GDP in the world with 1398.5 million inhabitants, and it is believed that in 2021, the gross domestic product (GDP) per capita was USD 12,640.

It is important to note that Chinese culture is also present in business and is strongly preserved by the natives. Therefore, a company wishing to internationalize in the country will need to have some basic knowledge of it. Within the six dimensions of culture mentioned in the previous chapter and defended by

Hofstede (

2022), it is possible to characterize Chinese culture. The first dimension is power distance, where China appears to be one of the highest-ranking countries; for the Chinese, inequalities between people are acceptable, and the relationship between subordinate and superior tends to be polarized, with no defense against the abuse of power by superiors. This is followed by individualism, where China appears to be a collectivist society, as the Chinese tend to put the interests of the group ahead of personal interests. In addition, personal relationships take precedence over the task and the company. The Chinese are cooperative with colleagues and can be hostile toward people outside the company. Third is masculinity. From this perspective, China is a masculine society, i.e., it is oriented and motivated toward success. This is visible in the fact that many Chinese people work late, often even keeping stores open all night, sacrificing family and leisure priorities. Workers in more rural areas leave their families to find better jobs and salaries in cities or other countries. Students are constantly worried about their exam results, as this will determine whether they succeed or fail. With regard to the fourth dimension, uncertainty aversion, it is important to note that the Chinese are comfortable with ambiguity, adapt easily to situations, and are entrepreneurial. This is followed by long-term orientation, which shows that Chinese culture is very pragmatic, i.e., people believe that the truth depends a lot on the situation, context, and time. In addition, the Chinese have a strong propensity to save and invest in order to obtain results.

According to data provided by the China Internet Network Information Center (2022), by June 2022, China had 1051 million internet users, an increase of 19.2 million compared with December 2021. As a result, the country is responsible for more than half of all B2C e-commerce worldwide. Currently, this form of commerce has been boosted by the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, China and e-commerce are increasingly important concepts for Portuguese companies and require priority dedication (

Falardo & Sequeira, 2021). In 2020, the Portuguese Agency for Investment and Foreign Trade (AICEP) established a partnership with the second largest e-commerce platform in China, JD.com, and created the first Portuguese marketplace in China, which was primarily dedicated to the wine trade. Chinese e-commerce attracts many companies because it has lower market entry costs associated with mobility, leading to less capital invested and fewer human resources required. What is more, it allows companies to increase their range of customers since the reach is greater, covering practically the entire Chinese territory, including the most rural areas (

Falardo & Sequeira, 2021).

China is one of the world’s top textile-exporting countries, and the level of exports continues to grow, which does not make importing any easier, as the country is a major producer. The country exports mainly to Europe, the USA, Japan, Hong Kong, and South Korea. In terms of production capacity, China remains the world leader (

Irun, 2017). In turn, according to the aforementioned author, fabrics and medical and healthcare textiles are the main imported products. The import of so-called technical textiles, i.e., products that are not manufactured for aesthetic purposes and where function is the main criterion, is increasing considerably, as the constant construction of infrastructures and the rapid development of the automotive, aerospace, and healthcare industries is driving their demand. The country imports mainly from Japan, Taiwan, Korea, and the United States, although imports from Europe are on the rise.

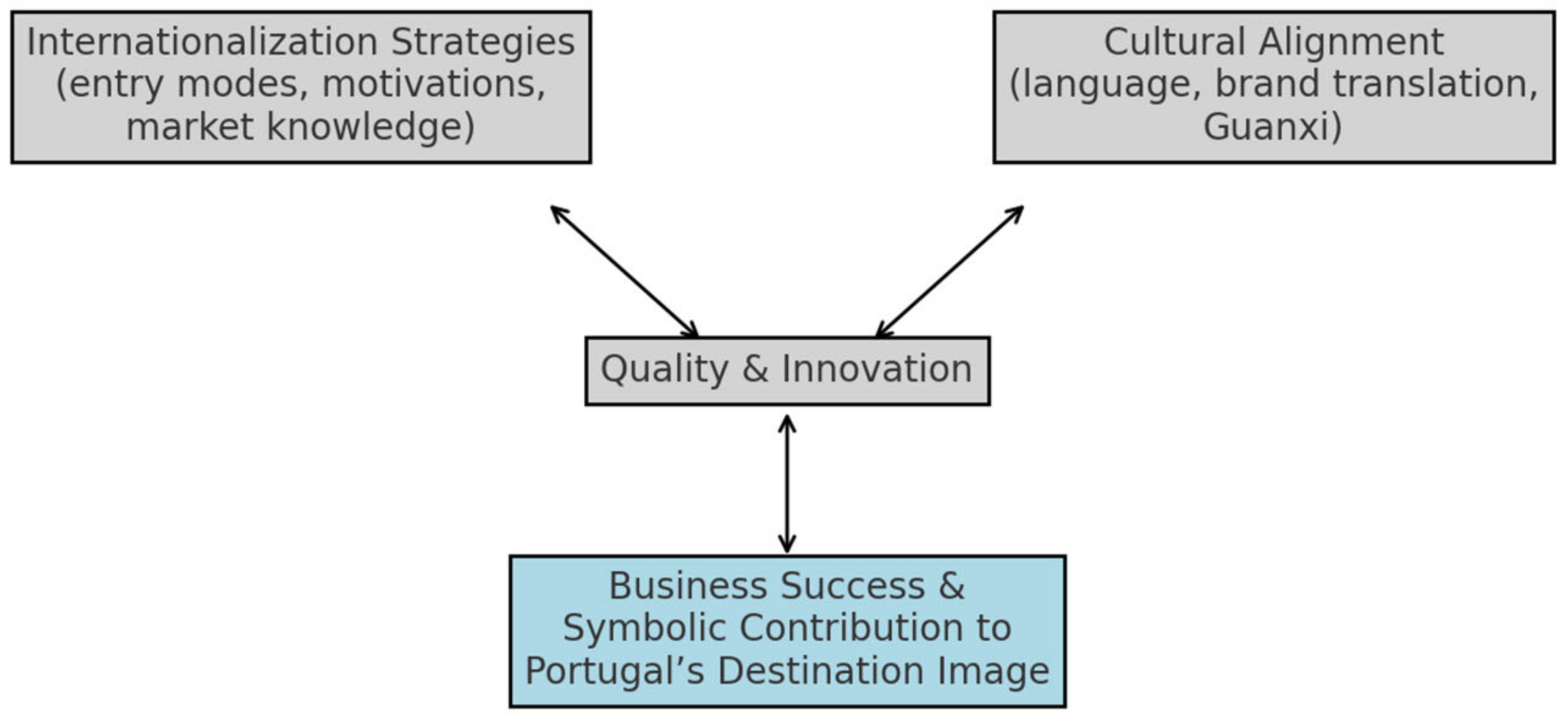

In this study, we propose an initial conceptual framework (

Figure 1) that positions internationalization strategies (entry modes, motivations, and market knowledge), cultural alignment (language, brand translation, and Guanxi), and quality and innovation as key factors influencing both business success and symbolic contributions to Portugal’s image as a destination. This framework guides our data collection and analysis process, which seeks to identify patterns through analytical generalization across two contrasting company profiles.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Research Design

This study adopts a qualitative, exploratory research design grounded in an inductive approach (

Campenhoudt et al., 2019;

Pinto da Costa, 2011). The aim is not to test preexisting theories but to generate insights from empirical data that inform the understanding of the internationalization process of Portuguese textile companies and their contribution to the destination image. This research seeks analytical generalization, in line with

Yin (

2014) approach to multiple-case design.

3.2. Empirical Context and Sampling

The empirical focus was on Portuguese companies in the textile sector that are either currently present in the Chinese market or preparing to enter it. The selection criteria included company size (micro, SME, or large), internationalization trajectory, and willingness to collaborate. A purposive sampling strategy was employed, aiming for diversity in terms of international experience and entry strategy, as presented in

Table 2. Two groups were defined: Group 1 (companies already operating in the Chinese market) and Group 2 (companies planning to enter China within the next 2 years). Each group included five companies selected through industry contacts and professional networks. All interviews were conducted between February and April 2024.

3.3. Data Collection

The primary research instrument was a semi-structured interview guide tailored to each group. The guides were developed based on the literature review and the initial conceptual framework, ensuring alignment with the research questions.

Group 1’s key dimensions included market trajectory and international experience; entry mode and motivations for choosing China; cultural and operational adaptations (e.g., brand, product, and Guanxi); knowledge of local legislation and e-commerce infrastructure; and perceptions of Portuguese brands in the Chinese market.

Group 2’s key dimensions included preparations for entry (strategic, cultural, and technological); perceived barriers (legislation, language, and market access); attitudes toward e-commerce and technological adaptation; level of understanding of Chinese consumer culture; and intended positioning and expectations of image impact.

All interviews were conducted via videoconference (Zoom or Google Meet), lasted between 20 and 40 min, and were audio-recorded with prior informed consent.

3.4. Data Analysis

Interview transcripts were subjected to thematic analysis using an iterative coding process supported by NVivo 14 software. Codes were initially derived from the literature and research questions and refined inductively during the data immersion phase. The themes were grouped into broader categories (e.g., cultural adaptation, e-commerce readiness, and perceived obstacles), allowing for cross-case comparison and identification of patterns across the two groups.

Thematic analysis followed

Braun and Clarke’s (

2006) six-phase approach, involving familiarization with data, initial coding, theme generation, review, definition, and a final write-up. Codes were developed inductively and grouped manually through axial comparisons across transcripts. While no software was used, all interviews were transcribed and cross-coded independently by two researchers to ensure consistency and mitigate bias. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion, and thematic saturation was assessed when no new codes emerged after the final two interviews in each group.

4. Analysis and Discussion of the Results

The analysis is presented according to the two study groups: companies already operating in China (Group 1) and companies preparing to enter the market (Group 2). Thematic categories were derived inductively and triangulated with the literature. Key quotations from the interviews are included to support the interpretation.

4.1. Group 1: Companies Operating in China

As presented in

Table 3, a set of five main themes emerged from the interviews with Group 1 (companies already operating in the Chinese market):

These results confirm the relevance of prior international maturity and the necessity of local intermediaries, echoing

Johanson & Vahlne (

1977) and

Dunning (

2001). Product adaptation and awareness of cultural markers (e.g., Guanxi and color symbolism) align with

Hofstede’s (

2022) dimensions and support the idea that successful internationalization requires more than operational readiness; it involves cultural and symbolic alignment.

4.2. Group 2: Companies Preparing to Enter China

Five main themes also emerged from Group 2, composed of companies planning to enter the Chinese market (

Table 4).

These interviews suggest that companies preparing to enter China tend to rely on intuition and generalized strategies, with limited cultural depth. While their desire for luxury positioning is in line with Group 1’s profile, the lack of operational or cultural preparation could jeopardize their positioning. As

Falardo and Sequeira (

2021) and

Hofstede (

2022) argued, understanding Chinese market norms is not optional; it is critical.

4.3. Cross-Group Synthesis and Final Conceptual Framework

As presented in

Table 5, a cross-case comparison revealed convergence and divergence between the two groups.

The final conceptual framework (

Figure 2) integrates the inductive themes across both groups, organizing them into three overarching dimensions: (1) strategic readiness, (2) cultural adaptation, and (3) contribution to destination image. This framework expands upon existing models (e.g., Uppsala, OLI, and Hofstede) by positioning the destination image not only because of tourism marketing but also as a collateral effect of industry-based internationalization.

Strategic readiness reflects the organizational capacity of firms to engage with complex international markets. It encompasses prior international experience, differentiation strategies, and entry modes adapted to the characteristics of the Chinese market. Firms that demonstrate higher strategic readiness tend to enter China through more sustainable and relational approaches, relying on accumulated market knowledge and tested business models. This dimension highlights the importance of experiential learning, risk management, and long-term vision in the internationalization process.

Cultural adaptation addresses the firms’ ability to align with the sociocultural fabric of the host market. This includes linguistic adaptation, sensitivity to symbolic systems (e.g., color, status, and tradition), and the capacity to navigate relational dynamics such as Guanxi. This dimension underscores that successful market penetration in China requires more than economic or logistic preparedness; it demands cultural intelligence and context-specific responsiveness. It also reinforces the argument that cultural fit is not an optional variable but a core determinant of strategic viability.

Contribution to the destination image captures how firms’ operations abroad affect perceptions of their country of origin (in this case, Portugal). By aligning brand values with notions of quality, exclusivity, and heritage, firms act as ambassadors of national identity. This dimension reframes internationalization as a soft power mechanism, whereby commercial activity contributes indirectly to the symbolic capital of the country. Thus, export-oriented industries do not merely project products; they export narratives, values, and identity.

In sum, the framework proposes a holistic understanding of internationalization that transcends economic rationale. It highlights the interplay between strategic action, cultural alignment, and symbolic outcomes. In the process, it suggests that national image is not exclusively constructed by public diplomacy or tourism campaigns but can also be actively shaped by business sectors that operate globally with intentionality and coherence.

5. Conclusions and Implications

This final section consolidates the main insights derived from the empirical analysis, articulating them into a set of theoretical reflections and practical recommendations. Drawing upon the inductive findings and the proposed conceptual framework, it highlights how internationalization strategies adopted by Portuguese textile firms—particularly in culturally complex markets like China—entail not only operational and strategic decisions but also symbolic and reputational consequences. The conclusions are structured into three subsections: key findings, theoretical contributions, and managerial implications. Each subsection offers a distinct lens through which to interpret the broader significance of this study.

5.1. Key Conclusions

This study examined the internationalization processes of Portuguese textile firms in relation to the Chinese market and explored the extent to which these processes contribute to shaping Portugal’s destination image abroad. Drawing on a comparative analysis of companies already operating in China and those preparing to, the findings revealed significant asymmetries in strategic preparation, cultural awareness, and symbolic capital deployment.

Firms currently active in the Chinese market tend to exhibit a high degree of strategic readiness, often grounded in extensive international experience and a clear understanding of the operational complexities involved in navigating high-context markets. Their reliance on local agents as entry facilitators reflects a pragmatic approach to market access, mitigating the risks associated with institutional distance and cultural unfamiliarity. Additionally, these firms progressively acknowledge the importance of cultural adaptation, particularly regarding symbolic codes (e.g., color use and communication rituals) and relationship-building mechanisms such as Guanxi.

In contrast, companies still planning to enter China display an overreliance on intuitive decision making and lack structured approaches to cultural learning, digital engagement, or destination image alignment. While many express ambitions of premium positioning, their strategies are not always supported by consistent branding or operational readiness. The Portuguese origin, although generally perceived as an asset by established firms, remains underutilized by those in preparatory phases, signaling a gap between strategic intent and symbolic articulation.

5.2. Theoretical Contributions

Theoretically, this research contributes to advancing knowledge in three distinct yet interconnected domains.

First, it extends internationalization theory by foregrounding the role of symbolic and cultural variables in firm-level international expansion. Unlike classical models such as the Uppsala model (

Johanson & Vahlne, 1977) or the OLI paradigm (

Dunning, 2001), which prioritize experiential knowledge and ownership-location-internalization advantages, this study highlights how symbolic alignment and perceived cultural fit increasingly mediate market entry success, particularly in culturally distant environments.

Second, the research offers a novel cross-disciplinary integration by connecting international business with destination image theory, traditionally rooted in the tourism and place branding literature. It reframes export-oriented firms as unintentional agents of place identity, suggesting that their branding, quality signaling, and cultural narratives can influence how the country of origin is perceived by consumers abroad, even in non-touristic domains.

Third, the inductive and qualitative design of this study generated a conceptual framework based on aggregated themes from two strategically different groups. This framework contributes to analytical generalization, offering a tool for understanding how strategic readiness, cultural adaptation, and destination image construction operate in tandem within the internationalization processes of SMEs in symbolism-intensive industries.

Furthermore, the findings challenge the linearity of the Uppsala model by illustrating how some firms rely not on incremental learning but on relational shortcuts (e.g., trusted intermediaries) to enter culturally distant markets. Similarly, while Hofstede’s framework helps explain symbolic adaptation strategies (such as color codes or Guanxi), the results suggest that firms often engage with these dimensions reactively rather than proactively, indicating a partial misalignment between theoretical assumptions and practical behavior.

5.3. Managerial Implications

For business decision makers, the findings provide actionable insights into how internationalization can be approached not only as a market access strategy but also as a means of soft power projection. Entering a market such as China demands a type of multidimensional readiness, one that encompasses logistics, strategic clarity, and deep cultural intelligence.

The central recommendation is for companies to extend beyond transactional thinking and instead integrate symbolic coherence into their internationalization plans. This involves ensuring that product design, communication strategies, and brand values resonate with local cultural expectations while remaining anchored in national identity. The “Portugal” brand, when strategically leveraged, can be a powerful differentiator, particularly in a market where authenticity, heritage, and perceived quality are highly valued.

Furthermore, managers should actively engage with China’s digital platforms and consumer ecosystems, recognizing that visibility and trust are co-constructed online. A passive or disconnected digital presence risks strategic invisibility in a market that prioritizes immediacy, interaction, and social validation.

Finally, while intermediaries may offer initial access and contextual knowledge, long-term success requires a move toward direct relational presence. This includes building internal capacities for cross-cultural negotiation, adapting business models to local consumption patterns, and developing continuous learning mechanisms for consumer behavior, legal frameworks, and market trends. In sum, internationalization should be viewed as a hybrid process of economic expansion and nation representation, where firms assume a dual role as commercial actors and narrative ambassadors.

5.4. Limitations and Future Research Directions

As with any qualitative and inductively driven study, this research presents certain limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the sample was limited to a select number of Portuguese textile companies either operating in or preparing to enter the Chinese market. While the two groups were analytically contrasted to enhance depth, the findings may not be statistically generalizable to the broader textile sector or to firms from other national contexts. Second, the data relied predominantly on self-reported perceptions through interviews, which may carry inherent biases linked to strategic positioning, selective memory, or subjective interpretation.

Moreover, although the study successfully identified inductive themes and patterns, it did not extend to a longitudinal assessment of market performance or brand impact over time. The dynamic nature of the Chinese market—characterized by evolving consumer preferences, regulatory shifts, and technological transformation—warrants a temporal lens that reaches beyond the static insights offered here.

Future research could explore several promising avenues. One direction would be to replicate this study across other sectors where national image plays a symbolic role (e.g., wine, ceramics, and design), allowing for cross-sectoral comparisons. Another would involve the inclusion of Chinese consumers’ or distributors’ perspectives to validate or challenge the assumptions made by Portuguese firms regarding branding, cultural adaptation, and perception of origin. Additionally, quantitative studies could be developed to test and refine the conceptual framework proposed here, using survey-based methods or structural equation modeling to assess relationships among the identified dimensions. Finally, future research should also explore how internationalization efforts contribute to place equity, or the long-term value of a country’s reputation as both a brand and a partner in global value chains.