A Framework on Eudaimonic Well-Being in Destination Competitiveness

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Cape Verde: Location and Characterization

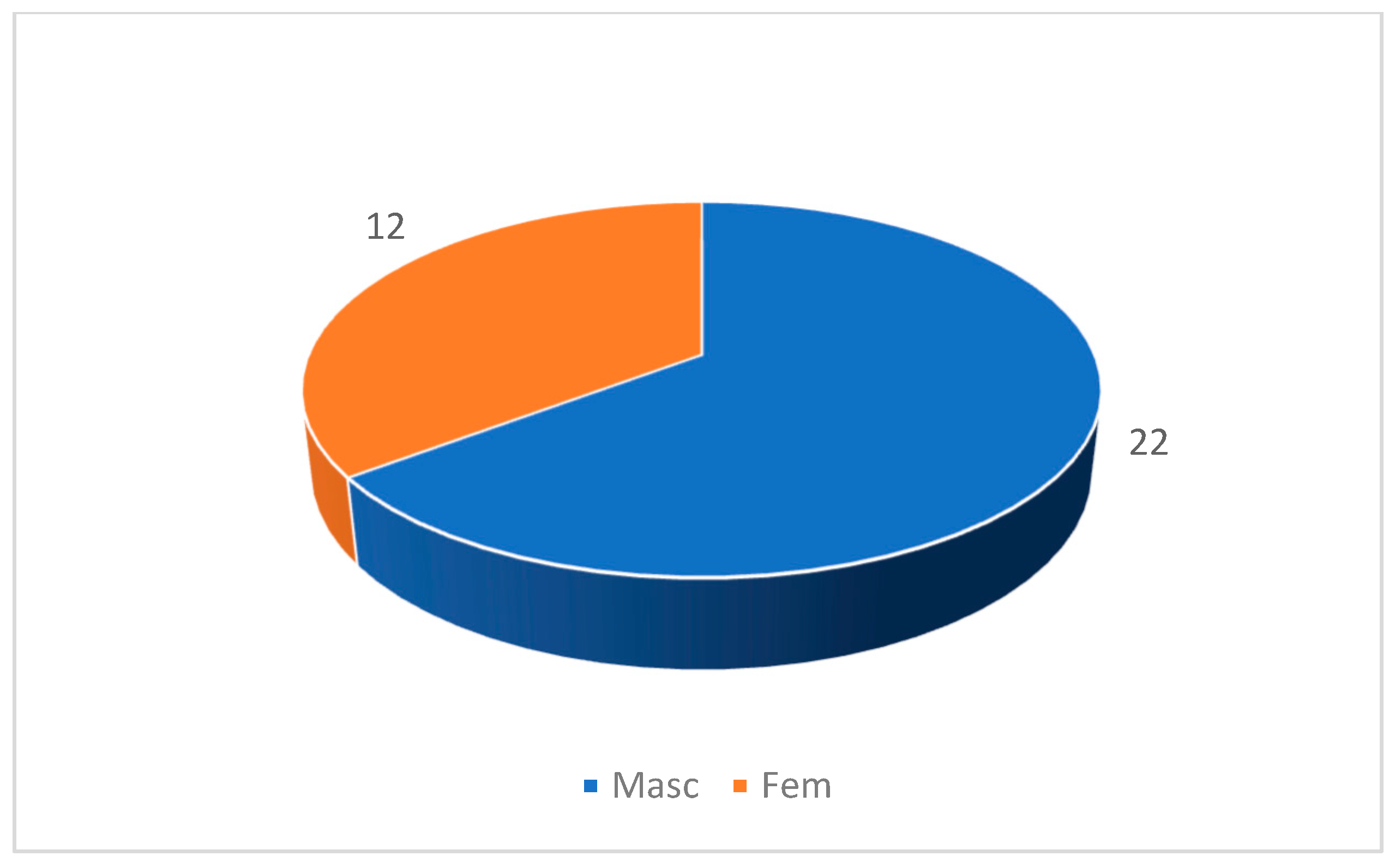

3.2. Procedure

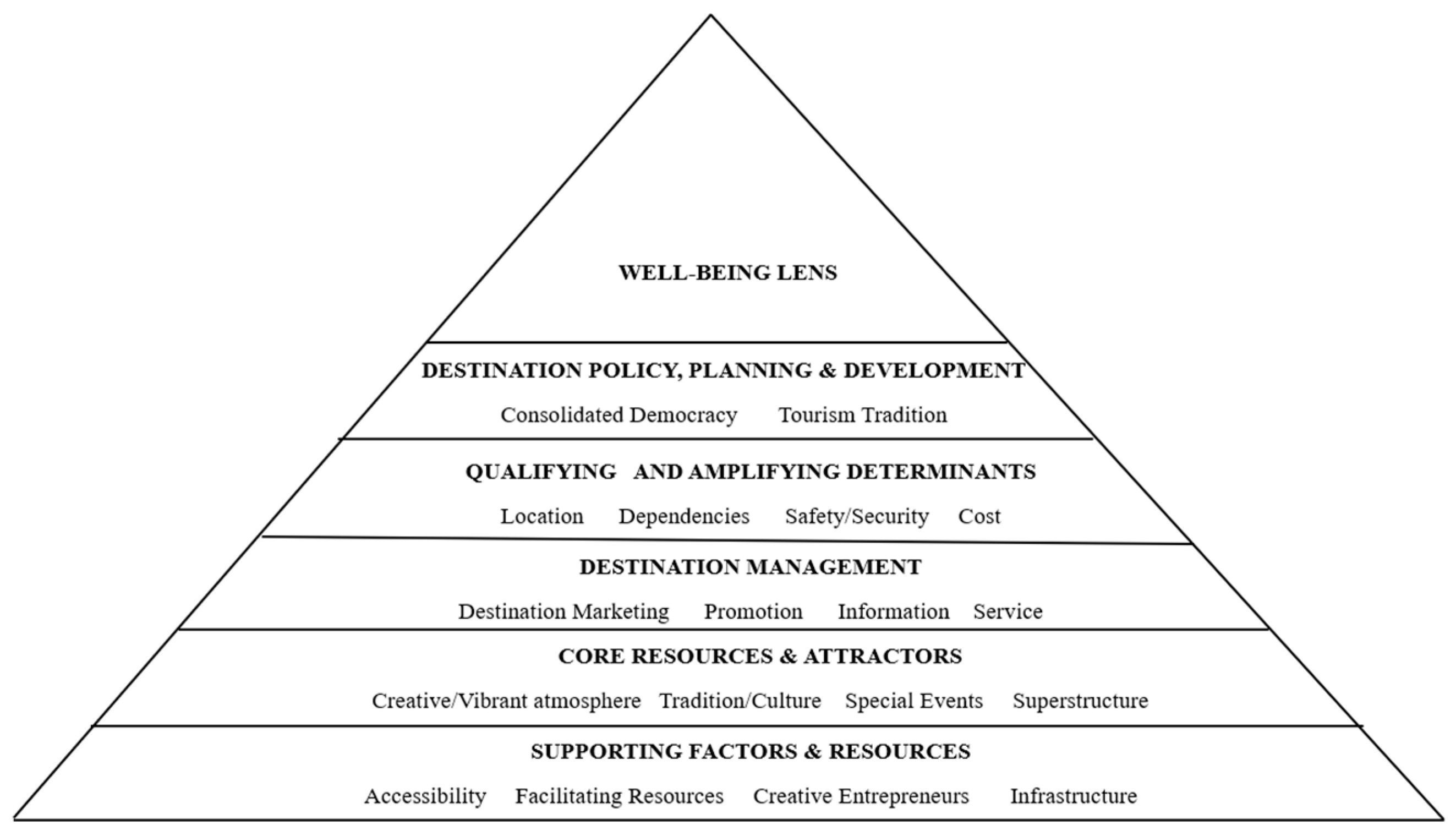

3.3. Tourism Competitiveness and Well-Being Framework

4. Results

4.1. Supporting Factors and Resources

4.2. Core Resources and Attractors

4.3. Destination Management

4.4. Qualifying and Amplifying Determinants

4.5. Destination Policy, Planning, and Development

4.6. Well-Being Lens

5. Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Managerial Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Entity/Company | Age | Gender | Duration (min) | Interview |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Director of Riu Palace (Boavista) | 40 | M | 20 | I1 |

| Director of Pestana Tropico (Santiago) | 58 | M | 44 | I2 |

| ITCV Administrator | 60 | M | 45 | I3 |

| Hotel Pérola | 30 | F | 38 | I4 |

| Agency IsaTour | 55 | F | 15 | I5 |

| President of CCS (Eastern Chamber of Commerce) | 65 | M | 50 | I6 |

| Praia Tour | 62 | F | 47 | I7 |

| President of Cape Verde Chamber of Tourism | 70 | M | 45 | I8 |

| Lecturer at Santiago University | 60 | F | 55 | I9 |

| Lecturer at Hotel School Santiago | 55 | F | 42 | I10 |

| Director of Executivotur Agency | 65 | F | 39 | I11 |

| International tourism local consultant | 50 | M | 48 | I12 |

| Praia City Hall | 60 | M | 54 | I13 |

| Tarrafal City Hall | 45 | M | 27 | I14 |

| Sal City Hall | 65 | M | 33 | I15 |

| São Vicente City Hall | 65 | M | 25 | I16 |

| EMAR (Sea School) | 42 | F | 40 | I17 |

| ENAPOR (Cape Verde Port Authority in São Vicente) | 40 | M | 37 | I18 |

| IMP (Maritime Port Institute)—São Vicente | 45 | M | 40 | I19 |

| IMP (Maritime Port Institute)—Sal | 54 | M | 26 | I20 |

| IMP (Maritime Port Institute)—Santiago | 38 | M | 25 | I21 |

| ONAVE—São Vicente | 41 | F | 37 | I22 |

| Port of Palmeira—Sal | 40 | M | 55 | I23 |

| Port of Praia—Santiago | 55 | M | 48 | I24 |

| Port of Tarrafal—Santiago | 61 | M | 59 | I25 |

| Director of Odjo d’Água Hotel (Sal) | 70 | M | 38 | I26 |

| Director of Oásis Salinas Sea Hotel (Sal) | 56 | M | 48 | I27 |

| Nice-Kriola | 55 | F | 35 | I28 |

| EMAR The School of the Sea | 39 | F | 58 | I29 |

| ISECMAR Higher Institute of Marine Engineering and Sciences | 38 | F | 47 | I30 |

| DNAP–National Directorate of Aquaculture and Fisheries | 42 | M | 39 | I31 |

| Interisland Transport of Cape Verde | 51 | M | 25 | I 32 |

| Ministry of Sea | 65 | M | 42 | I33 |

| São Vicente Marina Administration | 53 | F | 65 | I34 |

References

- Abreu-Novais, M., Ruhanen, L., & Arcodia, C. (2016). Destination competitiveness: What we know, what we know but shouldn’t and what we don’t know but should. Current Issues in Tourism, 19(6), 492–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agina, E., & Nwambuko, T. (2023). Assessing the relationship between infrastructural development and tourism destination competitiveness: Evidence from Nigeria. European Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Research, 11(1), 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, A., Cortez, L., & Klasen, S. (2014). LDC and other country groupings: How useful are current approaches to classify countries in a more heterogeneous developing world? (CDP Background Paper No. 21 ST/ESA/2014/CDP/21). UN Department of Economic & Social Affairs. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/dpad/wp-content/uploads/sites/45/publication/bp2014_21.pdf (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Alzaydi, Z., & Elsharnouby, M. (2023). Using social media marketing to pro-tourism behaviours: The mediating role of destination attractiveness and attitude towards the positive impacts of tourism. Future Business Journal, 9, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini, A., Khodadadi, M., & Khodadadi, M. (2024). Determinants and indicators of destination competitiveness: The case of Shiraz city, Iran. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 10(4), 1507–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrades-Caldito, L., Sánchez-Rivero, M., & Pulido-Fernández, J. (2013). Differentiating competitiveness through tourism image assessment: An application to Andalusia (Spain). Journal of Travel Research, 52(1), 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrow, K., Dasgupta, P., Goulder, L., Mumford, K., & Oleson, K. (2012). Sustainability and the measurement of wealth. Environment and Development Economics, 17(3), 317–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahar, O., & Kozak, M. (2007). Advancing destination competitiveness research: Comparison between tourists and service providers. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 22(2), 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballesteros, L., Poleacovschi, C., Weems, C., Zambrana, I., & Talbot, J. (2023). Evaluating the interaction effects of housing vulnerability and socioeconomic vulnerability on self-perceptions of psychological resilience in Puerto Rico. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 84, 103476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bank of Cape Verde (BCV). (2024). Main macroeconomic economic indicators. BCV. [Google Scholar]

- Bank of Portugal (BP). (2025). Evolution of the economies of PALOP and Timor-Leste 2023–2024. Bank of Portugal. [Google Scholar]

- Baruca, P., & Čivre, Z. (2023). Unique destination attributes as a basis of tourism experience. Academica Turistica, 15(3), 349–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berbekova, A., Uysal, M., & Assaf, A. (2022). Toward an assessment of quality of life indicators as measures of destination performance. Journal of Travel Research, 61(6), 1424–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birmingham, H. (2019). Development characteristics of small island developing states. K4D. [Google Scholar]

- Boukas, N. (2019). Rural tourism and residents’ well-being in Cyprus: Towards a conceptualised framework of the appreciation of rural tourism for islands. International Journal of Tourism Anthropology, 7(1), 60–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramwell, B., & Rawding, L. (1996). Tourism marketing images of industrial cities. Annals of Tourism Research, 23(1), 201–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y., Ma, J., & Lee, Y. (2020). How do Chinese travelers experience the arctic? Insights from a hedonic and eudaimonic perspective. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 20(2), 144–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canovi, M., & Pucciarelli, F. (2019). Social media marketing in wine tourism: Winery owners’ perceptions. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 36(6), 653–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). (2025). The world factbook. CIA. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G., Zhao, C., & Li, C. (2025). Mental health and well-being in tourism: A horizon 2050 paper. Tourism Review, 80(1), 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chon, K., Weaver, P., & Kim, C. (1991). Marketing your community image analysis in Norfolk. The Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 31(4), 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clissold, R., Westoby, R., McNamara, K., & Fleming, C. (2022). Wellbeing outcomes of nature tourism: Mt Barney Lodge. Annals of Tourism Research Empirical Insights, 3(2022), 100077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coke, K. (2023). Comparative Analysis of sustainable development in highly populated small island developing states (SIDS) in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC). Hofstra University. [Google Scholar]

- Croes, R., Renduchintala, C., & Badu-Baiden, F. (2024). Reimagining indigenous tourism: The RISE framework. Tourism Planning & Development, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouch, G., & Ritchie, J. (1999). Tourism, competitiveness and societal prosperity. Journal of Business Research, 44(3), 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvelbar, L., Grün, B., & Dolnicar, S. (2017). Which hotel guest segments reuse towels? Selling sustainable tourism services through target marketing. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(7), 921–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, P., Dias, A., & Patuleia, M. (2020). The impacts of tourism on cultural identity on Lisbo historic neighbourhoods. Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Studies, 8(1), 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daneels, R., Bowman, N., Possler, D., & Mekler, E. (2021). The ‘eudaimonic experience’: A scoping review of the concept in digital games research. Media and Communication, 9(2), 178–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datiko, D. (2024). Capable of anything: Ethiopian women and tourism. Tourism Planning & Development, 22(1), 41–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, A., Rosário, M., & Patuleia, M. (2023). Creative tourism destination competitiveness: An integrative model and agenda for future research. Creative Industries Journal, 16(2), 180–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, I., Ross, D., & Gomes, A. (2018). The clustering conditions for managing creative tourism destinations: The Alqueva region case, Portugal. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 61(4), 635–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dornbach-Bender, A., Ruggero, C., Smith, P., Schuler, K., Bennett, C., Neumann, C., & Callahan, J. (2020). Association of behavioral activation system sensitivity to lower level facets of positive affect in daily life. Personality and Individual Differences, 152, 109570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draçi, P., & Kraja, G. (2023). Community support for sustainable tourism strategies is an important factor in its successful development. Economic Insights—Trends and Challenges, 12(1), 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drake, G. (2003). This place gives me space. Place and Creativity in the Creative Industries, 34(4), 511–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duxbury, N., & Richards, G. (2019). A research agenda for creative tourism. Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Duxbury, N., Silva, S., & Vinagre, T. (2019). Creative tourism development in smal cities and rural areas in Portugal: Insights from start-up activities. In D. A. Jelinčić, & Y. Mansfeld (Eds.), Creating and managing experiences in cultural tourism (pp. 1–17). World Scientific Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer, L. (2022). Destination competitiveness and resident well-being. Tourism Management Perspectives, 43, 100996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, L., & Kim, C. (2003). Destination competitiveness: Determinants and indicators. Current Issues in Tourism, 6(5), 369–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enright, M., & Newton, J. (2004). Tourism destination competitiveness: A quantitative approach. Tourism Management, 25(6), 777–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enright, M., & Newton, J. (2005). Determinants of tourism destination competitiveness in Asia Pacific: Comprehensiveness and universality. Journal of Travel Research, 43(4), 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandéz, J., Martínez, J., & Martín, J. (2022). An analysis of the competitiveness of the tourism industry in a context of economic recovery following the COVID 19 pandemic. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 174, 121301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernando, I., & Long, W. (2012). New Conceptual Model on Cluster Competitiveness: A New Paradigm for Tourism? International Journal of Business and Management, 7(9), 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flick, U. (2022). An introduction to qualitative research (7th ed.). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzáles-Santiago, M., Loureiro, S., Langaro, D., & Ali, F. (2024). Adoption of smart technologies in the cruise tourism services: A systematic review and future research agenda. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology, 15(2), 285–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubrium, J., & Holstein, J. (2001). From the individual interview to the interview society. In J. F. Gubrium, & J. A. Holstein (Eds.), Handbook of interview research (pp. 3–32). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Delgado, E. (2024). Coastal Restoration challenges and strategies for small island developing states in the face of sea level rise and climate change. Coasts, 4, 235–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoarau, H. (2014). Knowledge acquisition and assimilation in tourism-innovation processes. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 14(2), 135–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y., & Ritchie, J. (1993). Measuring destination attractiveness: A contextual approach. Journal of Travel Research, 35(4), 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, S., Ritchie, B., & Timur, S. (2004). Measuring destination competitiveness: An empirical study of Canadian ski resorts. Tourism and Hospitality Planning & Development, 1(1), 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iriarte, L., & Musikanski, L. (2019). Bridging the gap between the sustainable development goals and happiness metrics. International Journal of Community WellBeing, 1(2), 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J. (2001). In-depth interviewing. In J. Gubrium, & J. Holstein (Eds.), Handbook of interview research (pp. 103–121). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Jørgensen, M. T., Vorre Hansen, A., Sørensen, F., Fuglsang, L., Sundbo, J., & Jensen, F. (2021). Collective tourism social entrepreneurship: A means for community mobilization and social transformation. Annals of Tourism Research, 88, 103171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J. (2020). Identifying antecedents and consequences of well-being: The case of cruise passengers. Tourism Management Perspectives, 33, 100609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoi, N., & Le, A. (2022). Is coolness important to luxury hotel brand management? The linking and moderating mechanisms between coolness and customer brand engagement. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 34(7), 2425–2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantopoulou, C., Varelas, S., & Liargovas, P. (2024). Well-being and tourism: A systematic literature review. Economies, 12, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legatzke, H., Current, D., & LaPan, C. (2024). Applying the sustainable livelihoods framework to examine the efficacy of community-based tourism at equitably promoting local livelihood opportunities. Tourism Planning & Development, 22(3), 346–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, S., Paliszkiewicz, J., & Roopnarine, R. (2024). Examining the interrelationships between knowledge sharing, knowledge transfer, and knowledge gaps in the water sector of Caribbean small island developing states (SIDS). Issues in Information Systems, 25(4), 46–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llena-Nozal, A., Martin, N., & Murtin, F. (2019). The economy of well-being. Creating opportunities for people’s well-being and economic growth. In OECD Statistics Working Papers 2019/02. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, Z., Zhao, W., Liu, Y., Wu, J., & Hou, M. (2024). Impact of perceived value, positive emotion, product coolness and Mianzi on new energy vehicle purchase intention. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 76, 103564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makwembere, S., Acha-Anyi, P., Asaleye, A., & Garidzirai, R. (2024). Can remittance promote tourism income and inclusive gender employment? Function of migration in the South African economy. Economies, 12, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matz, J., & Linguère, M. (2023). Migration and the autonomy of women left behind. European Journal of Development Research, 35(5), 1059–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd-Saufi, S., Azinuddin, M., Som, A., & Hanafiah, M. (2024). Overtourism impacts on Cameron Highlands community’s quality of life: The intervening effect of community resilience. Tourism Planning & Development, 22(2), 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mycoo, M. A. (2018). Beyond 1.5 °C: Vulnerabilities and adaptation strategies for Caribbean small island developing states. Regional Environmental Change, 18(8), 2341–2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mycoo, M. A., & Roopnarine, R. R. (2024). Water resource sustainability: Challenges, opportunities and research gaps in the English-speaking Caribbean small island developing states. PLoS Water, 3(1), e0000222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasira, M., Mohamada, M., Ab Ghania, N., & Afthanorhana, A. (2020). Testing mediation roles of place attachment and tourist satisfaction on destination attractiveness and destination loyalty relationship using phantom approach. Management Science Letters, 10, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, D., & Graham, J. (2018). Religion and well-being. Handbook of well-being. DEF Publishers (:nobascholar.com). [Google Scholar]

- OECD. (2018). Making development Co-operation work for small island developing states. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, D. (1997). Competitive destination analysis in Southeast Asia. Journal of Travel Research, 35(4), 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, A. (1993). Tourism, technology and competitive strategies. CAB International. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M. (1990). The competitive advantage of nations. The Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez-Guerrero, G., Fernández-Enríquez, A., Chica-Ruiz, J. A., García-Onetti, J., & Arcila-Garrido, M. (2024). The territorialization of cultural heritage as an opportunity for its adaptive reuse from the tourist management. Tourism Planning & Development, 22, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remoaldo, P., & Cadima-Ribeiro, J. (2019). Creative tourism as a new challenge to the development of destinations: The Portuguese case study. In M. Peris-Ortiz, M. Cabrero-Flores, & A. Serrano-Santoyo (Eds.), Cultural and Creative Industries (pp. 81–99). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Republic of Cape Verde. (2019). GOPEDS. Ministry of Economics.

- Ritchie, J., & Crouch, G. (1993). Competitiveness in international tourism: A framework for understanding and analysis (pp. 23–71). World Tourism Education and Research Centre, University of Calgary. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie, J., & Crouch, G. (2000). The competitive destination: A sustainability perspective. Tourism Management, 21(1), 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, J., & Crouch, G. (2003). The competitive destination: A sustainable tourism perspective. CABI Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Ritpanitchajchaval, N., Suwaree, A., & Apollo, M. (2023). Eudaimonic well-being development: Motives driving mountain-based adventure tourism. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, 42(2023), 100607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C., Boylan, J., & Kirsch, J. (2021). Eudaimonic and hedonic well-being. Measuring well-being. In M. T. Lee, L. Kubzansky, T. Vande, & J. Weele (Eds.), Measuring well-being interdisciplinary perspectives from the social sciences and the humanities (pp. 92–135). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Saayman, M., Li, G., Uysal, M., & Song, H. (2018). Tourist satisfaction and subjective well-being: An index approach. International Journal of Tourism Research, 20(3), 388–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J. (2019). Introduction to the 2019 global happiness and wellbeing policy report. Global Council for Happiness and Wellbeing. Available online: https://www.jeffsachs.org/reports/llgy5tr889dtnnnz33bdg3sb8cnftw (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Santos-Júnior, A., Almeida-Garcia, F., Morgado, P., & Mendes-Filho, L. (2020). Residents’ quality of life in smart tourism destinations: A theoretical approach. Sustainability, 12(20), 8445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmento, E. M., & Silva, A. L. (2024). Cape Verde: Islands of vulnerability or resilience? A transition from a MIRAB model into a TOURAB one? Tourism Hospitality, 5, 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M., & Diekmann, A. (2017). Tourism and wellbeing. Annals of Tourism Research, 66, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofield, T., Guia, J., & Specht, J. (2017). Organic ‘folkloric’ community driven place-making and tourism. Tourism Management, 61, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soh, A., Puah, C., & Arip, M. (2023). A bibliometric analysis on tourism sustainable competitiveness research. Sustainability, 15(2), 1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiglitz, J. E., Fitoussi, J.-P., & Durand, M. (2018a). Beyond GDP: Measuring what counts for economic and social performance. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiglitz, J. E., Fitoussi, J.-P., & Durand, M. (2018b). For good measure: Advancing research on well-being metrics beyond GDP (pp. 163–202). OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X., & Xu, H. (2019). Role shifting between entrepreneur and tourist: A case study on Dali and Lijiang, China. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 37(5), 547–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.-K., Tan, S.-H., Luh, D.-B., & Kung, S.-F. (2016). Understanding tourist perspectives in creative tourism. Current Issues in Tourism, 19(10), 981–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A., Baptiste, A., Martyr-Koller, R., Pringle, P., & Rhiney, K. (2020). Climate change and small island developing states. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 45, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tov, W. (2018). Well-being concepts and components. In E. Diener, S. Oishi, & L. Tay (Eds.), Handbook of well-being. DEF Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, K., Truong, A., Truong, V., & Luu, T. (2024). Leveraging brand coolness for building strong consumer-brand relationships: Different implications for products and services. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 33(2), 258–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trupp, A., Salman, A., Stephenson, M., Chan, L., & Gan, J. (2024). A systematic review of challenges faced by micro and small enterprises in tourism destinations: Producing solutions through resilience building and sustainable development. Tourism Planning & Development, 22, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). (2024). The 2023/2024 human development report: Breaking the gridlock. UNDP. [Google Scholar]

- Ventura, R., Fernandes, E., Cabo, M., Carvalho, C., Fernandes, V., & Tshikovhi, N. (2024). Socioeconomic factors driving international travel destination for tourism. Tourism Planning & Development, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vojtko, V., Štumpf, P., Rašovská, I., McGrath, R., & Ryglov, A. (2022). Removing uncontrollable factors in benchmarking tourism destination satisfaction. Journal of Travel Research, 61(1), 136–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, C., Batra, R., Loureiro, S., & Bagozzi, R. (2019). Brand Coolness. Journal of Marketing, 83(5), 36–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WEF. (2020). The global competitiveness report 2019. World Economic Forum. [Google Scholar]

- Wendt, G., Costa, A., Poletto, M., Cassepp-Borges, V., Dellaglio, D., & Koller, S. (2019). Stressful events, life satisfaction, and positive and negative effects in youth at risk. Children and Youth Services Review, 102, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, E., Melik, R., & Bendle, J. (2024). Perceived impacts of tourism on community identity: Perspectives of two scottish highland communities. Tourism Planning & Development, 21(6), 917–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. (2022). Resilient transport in small island developing states: From a call for action to action. World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- World Travel & Tourism Council (WTTC). (2023). Travel & tourism economic impact 2023: Cape Verde. World Travel & Tourism Council. [Google Scholar]

- World Travel & Tourism Council (WTTC). (2024). Travel barometer. World Travel & Tourism Council. [Google Scholar]

- Woyo, E., & Slabbert, E. (2023). Competitiveness factors influencing tourists’ intention to return and recommend: Evidence from a distressed destination. Development Southern Africa, 40(2), 243–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C., Cole, S., & Chancellor, C. (2018). Resident support for tourism development in rural mid-western (USA) communities: Perceived tourism impacts and community quality of life perspective. Sustainability, 10(3), 802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G., Sirgy, M., & Bosnjak, M. (2021). The effects of holiday leisure travel on subjective well-being: The moderating role of experience sharing. Journal of Travel Research, 60(8), 1677–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., & Xie, P. (2019). Motivational determinates of creative tourism: A case study of Albergue art space in MACAU. Current Issues in Tourism, 22(20), 2538–2549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sarmento, E.M.; Loureiro, S.; Mendes, Z.; Monteiro, J.M.; Fernandes, S. A Framework on Eudaimonic Well-Being in Destination Competitiveness. Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 135. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6030135

Sarmento EM, Loureiro S, Mendes Z, Monteiro JM, Fernandes S. A Framework on Eudaimonic Well-Being in Destination Competitiveness. Tourism and Hospitality. 2025; 6(3):135. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6030135

Chicago/Turabian StyleSarmento, Eduardo Moraes, Sandra Loureiro, Zorro Mendes, José Mascarenhas Monteiro, and Sandra Fernandes. 2025. "A Framework on Eudaimonic Well-Being in Destination Competitiveness" Tourism and Hospitality 6, no. 3: 135. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6030135

APA StyleSarmento, E. M., Loureiro, S., Mendes, Z., Monteiro, J. M., & Fernandes, S. (2025). A Framework on Eudaimonic Well-Being in Destination Competitiveness. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(3), 135. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6030135