Abstract

Tourism development in coastal zones is often guided by marketing strategies focused on promotion, without real integration with the ecological, identity, and planning challenges facing these territories. This disconnection compromises environmental resilience, dilutes local cultural identity, and hinders adaptive governance in contexts of increasing tourism pressure and climate change. In response to this problem, the article presents the concept of Blue Marketing, a place-based, sustainability-oriented approach designed to guide communication, product development, and governance in marine and coastal destinations. Drawing on socio-environmental marketing and inspired by Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM), the study proposes a Blue Marketing Decalogue (BMD), structured into three thematic blocks: (1) Ecosystem-focused sustainability, (2) cultural identity and territorial uniqueness, and (3) strategic planning and adaptive governance. Methodologically, the decalogue is empirically grounded in a territorial diagnosis of the Barbate–Vejer coastal corridor (Cádiz, Spain), developed through Geographic Information Systems (GIS), local planning documents, and field observations. This case study provides a detailed analysis of ecological vulnerabilities, cultural resources, and tourism dynamics, offering strategic insights transferable to other coastal contexts. The BMD incorporates both strategic and normative instruments that support the design of responsible tourism communication strategies, aligned with environmental preservation, community identity, and long-term planning. This contribution enriches current debates on sustainable tourism governance and provides practical tools for coastal destinations aiming to balance competitiveness with ecological responsibility. Ultimately, Blue Marketing is proposed as a vector for transformation, capable of reconnecting tourism promotion with the sustainability challenges and opportunities of coastal regions.

1. Introduction

The development of coastal tourism has brought significant economic benefits to many seaside communities, enhancing local economies and creating new employment opportunities. However, it has also increased pressure on fragile ecosystems, particularly in municipalities that host Protected Natural Areas (PNAs), where the balance between tourism and conservation is delicate and increasingly difficult to maintain (Hall, 2011; Sánchez Aparicio, 2012). The growing demand for coastal tourism, often concentrated in specific periods and spaces, has led to negative externalities such as biodiversity loss, habitat degradation, and cultural homogenization (Mier-Terán Franco, 2006; Rodríguez Rodriguez, 2009).

Conventional tourism planning strategies have often proved insufficient to address these challenges, especially in coastal and marine environments that require a nuanced understanding of ecological fragility and socio-economic dynamics. In this context, there is an urgent need for new approaches that can integrate environmental conservation and sustainable tourism development in coastal territories (Griggs et al., 2013; Sumarmi et al., 2024).

Likewise, despite the advances in sustainable and socio-environmental marketing, most existing frameworks remain insufficiently adapted to the specific complexities of coastal tourism. They often lack spatial sensitivity, overlook ecological thresholds, and fail to engage with governance systems. In particular, current marketing approaches are rarely integrated into planning frameworks, resulting in a disconnect between promotional narratives and the actual socio-ecological conditions of coastal areas. This conceptual and operational gap justifies the development of a dedicated strategic approach—Blue Marketing—that addresses these limitations and redefines the role of marketing as a mediator between sustainability goals and territorial realities.

This article introduces the concept of Blue Marketing, an innovative strategy that adapts the tools of sustainable and socio-environmental marketing specifically to the context of coastal tourism management. This approach seeks to promote responsible tourism models that enhance environmental conservation, support local communities, and foster the protection of traditional coastal lifestyles. It builds upon established frameworks of environmental marketing (Peattie, 2001; Kotler & Lee, 2005a), sustainable tourism principles (UNEP & UNWTO, 2005), and the European Commission’s “Blue Growth” strategy, adapting them to the specific conditions of marine-coastal spaces. The importance of Blue Marketing lies in its ability to integrate territorial diagnosis, strategic planning, action implementation, and monitoring within a flexible but structured framework. This approach recognizes coastal areas as complex socio-ecological systems where tourism development must be aligned with conservation objectives, social engagement, and sustainable economic practices.

The main objective of this study is to propose a decalogue of principles for applying Blue Marketing strategies in coastal tourism destinations, based on theoretical insights and empirical experience derived from a case study in Barbate and Vejer de la Frontera (Spain).

Specifically, the article pursues the following specific objectives (SO):

- SO1:

- To conceptualize and formulate a set of normative principles (a decalogue) for guiding Blue Marketing strategies in coastal tourism contexts.

- SO2:

- To ground the proposed principles in empirical analysis from a coastal case study.

- SO3:

- To contribute to the academic and practical debates on sustainable tourism development in coastal areas by formulating a normative and transferable set of principles that integrate marketing, environmental conservation, and cultural heritage management under a unified strategic vision.

Numerous cases illustrate the tensions between tourism marketing and sustainability. In destinations like Venice, Barcelona, or the Galápagos Islands, promotional campaigns have contributed to overtourism by emphasizing iconic visuals while omitting the carrying capacity limits or the socio-environmental consequences of visitor influx (Pahrudin et al., 2022; Mutiarasari et al., 2025). In many coastal areas, including the Andalusian coast, marketing materials often rely on generic beach imagery, sun-and-sand clichés, or aestheticized Instagram visuals that erase local culture and ignore ecological fragility. This type of representation contributes to a distorted perception of destination resilience and promotes mass tourism disconnected from environmental or community concerns (Gryshchenko et al., 2022). Moreover, the increasing use of greenwashed narratives—such as vague claims of “eco-friendliness” without measurable backing—undermines trust and hinders meaningful sustainability transitions in tourism communication (Sneideriene & Legenzova, 2025). These examples demonstrate the risks of marketing strategies that prioritize short-term appeal over long-term responsibility, reinforcing the need for new frameworks grounded in ecological awareness and territorial authenticity.

In view of the above, this study addresses the following research questions:

- RQ1:

- What normative principles can guide the integration of sustainability, cultural identity, and governance into coastal tourism marketing strategies?

- RQ2:

- How can these principles be informed by empirical insights from a territorial case study, and to what extent are they transferable to other coastal contexts?

- RQ3:

- What role can tourism marketing play as a mediating function between environmental planning, local identity, and the competitiveness of tourism destinations?

2. Background and Conceptual Foundations of Blue Marketing

This section provides a literature review on the object of study. The concept of sustainable tourism gained significant attention after the publication of Our Common Future (WCED, 1987) and the subsequent definitions provided by international organizations such as the World Tourism Organization. Sustainable tourism seeks to balance environmental conservation, economic profitability, and social equity, ensuring that tourism development meets present needs without compromising the ability of future generations. In coastal areas, where high ecological value converges with intense tourist activity, sustainable planning becomes even more critical (Barragán Muñoz et al., 2020; Iamkovaia et al., 2020; Baloch et al., 2022). These environments exhibit particular vulnerability due to the interdependence of marine and terrestrial ecosystems, limited resilience to anthropogenic impacts, and accelerating threats related to climate change, such as coastal erosion and biodiversity loss.

Over the years, various models such as carrying capacity assessments (Arisci et al., 2003; Ajuhari et al., 2023) and integrated environmental management tools (UNEP & UNWTO, 2005) have been developed to address these challenges. Nevertheless, coastal destinations continue to face critical limitations. One key issue is the disconnection between tourism promotion and spatial or environmental planning, which often results in incoherent strategies, overpromotion, and the neglect of territorial constraints (Butler, 1991; Hall, 2008; Bramwell & Lane, 2011; Ramírez-Guerrero et al., 2025). This lack of integration has been identified as a structural weakness in destination governance, where communication remains dissociated from planning instruments and sustainability goals.

These perspectives resonate with cultural sustainability frameworks that stress the relational and regenerative dimensions of place-based tourism. Duxbury and Campbell (2011) emphasized the importance of cultural practices in revitalizing rural and coastal areas, particularly through creative industries, participatory governance, and bottom-up cultural policy design. In particular, Duxbury et al. (2025) highlight how smaller communities can leverage local cultural narratives and artistic expression to foster regenerative tourism, aligning closely with the aims of the Blue Marketing Decalogue proposed in this article.

A second major challenge is the loss of cultural identity and the homogenization of destination narratives, often caused by globalized branding practices that fail to reflect local distinctiveness (Richards, 2011; Hernández-Mogollón et al., 2018; Timothy, 2024). A paradigmatic example is the case of Barcelona, where tourism marketing campaigns emphasizing cosmopolitanism and lifestyle branding contributed to excessive tourist influx and residential displacement, with insufficient attention to spatial carrying capacity or resident well-being (Elorrieta et al., 2022). Similar patterns have occurred in other coastal cities like Dubrovnik or Bali, where aggressive branding has led to tensions between tourism growth and socio-environmental sustainability.

Many coastal territories possess valuable cultural resources linked to maritime heritage, traditional livelihoods, and symbolic landscapes, yet these are frequently underrepresented or oversimplified in promotional content.

As branding becomes increasingly homogenized and disconnected from local identity, destinations risk becoming indistinguishable and culturally diluted, undermining both their authenticity and their long-term competitiveness (Aman et al., 2024).

Thirdly, the literature has highlighted the ecological consequences of unsustainable tourism communication, especially when marketing reinforces extractive or high-impact tourism patterns. Dodds and Holmes (2018) and He et al. (2024) note that marketing is still too often focused on mass appeal, neglecting its potential to foster environmental awareness and responsible behavior among tourists.

In this context, Integrated Coastal Zone Management (hereinafter ICZM) offers a valuable conceptual framework to address these structural imbalances, as it promotes coordination between sectors, participatory governance, and conservation of both natural and cultural resources (De Andrés García & Barragán Muñoz, 2020). However, its application to tourism remains limited, partly due to the absence of specialized marketing tools that align with ICZM principles while addressing the specific needs of tourism management (Mestanza-Ramón et al., 2020).

In parallel, marketing theory has evolved toward more responsible and socially committed approaches. Since the 1970s, social marketing has been defined as the application of marketing principles to influence behaviors that benefit individuals and society (Kotler & Zaltman, 1971). This was followed by the emergence of environmental and sustainable marketing, which seeks to align consumption and promotion with conservation values (Peattie, 2001; Kotler & Lee, 2005b). In the Spanish-speaking academic context, Mier-Terán Franco (2006) introduced the concept of socio-environmental marketing, emphasizing strategies to influence voluntary behavior in favor of ecosystem protection and resource management.

Scholars have emphasized the complex and often contradictory relationship between coastal tourism, cultural identity, and environmental degradation. In Southeast Asia and the Pacific, tourism expansion has frequently clashed with traditional livelihoods, especially under top-down planning and commodified branding strategies (Biddulph, 2020; Fabinyi et al., 2022; Van et al., 2024). In Latin America, community-based approaches advocate for alternatives rooted in social justice and territorial autonomy (Vargas-Lama & Osorio-Vera, 2020; Lang, 2022). These perspectives call for governance frameworks that are inclusive, bottom-up, and culturally sensitive. However, most marketing approaches—whether global or local—still lack territorial specificity and often frame destinations generically; ignoring the ecological and sociocultural complexity of coastal systems (Simancas Cruz et al., 2022). They also tend to overlook the governance dimension of tourism, limiting their ability to support adaptive management or meaningful stakeholder engagement. These limitations underline the need for an adapted framework capable of integrating environmental sustainability, reinforcement of local identity, and tourism competitiveness in marine-coastal territories.

To develop an operational model grounded in the governance needs of coastal territories, this proposal draws upon established frameworks in integrated coastal planning. Specifically, it is inspired by ICZM frameworks, particularly the widely recognized decalogue formulated by Barragán Muñoz (2003, 2014), which outlines key principles for effective coastal governance. Following a similar logic, the present research aims to elaborate a decalogue adapted to the field of tourism marketing, an area where specific guidelines for coastal zones are still lacking despite the increasing sustainability challenges faced by these destinations.

Recent contributions in sustainable tourism and governance have called for deeper transformations in how destinations approach planning, identity, and communication. Scholars such as Nitsch and Vogels (2022) advocate for regenerative tourism models that go beyond mitigation, seeking structural change and community empowerment. In parallel, Zhang et al. (2024) questions the limitations of stakeholder-based participation, highlighting the need for more inclusive and context-sensitive governance in tourism planning. These perspectives converge with calls for adaptive governance in coastal territories, particularly in insular and vulnerable contexts (Schlüter et al., 2020). From a communication standpoint, He et al. (2024) demonstrate how message framing can shape pro-environmental tourist behavior, supporting the strategic potential of marketing tools aligned with sustainability.

While these approaches enrich the sustainability debate, they often lack concrete mechanisms for integrating marketing into governance processes or translating values into strategic communication models. Moreover, their applicability may be limited in territories with fragmented institutions, high tourism dependency, or culturally embedded narratives that resist standardized solutions. Blue Marketing could respond to this gap, offering a normative, transferable, and territory-sensitive framework that operationalizes sustainability, cultural identity, and participatory governance within tourism communication—particularly in coastal destinations that face mounting pressures and require contextually adapted planning tools. It is within this context that the concept of Blue Marketing emerges as a necessary innovation. This new approach proposes a specialized application tailored to the particularities of coastal and marine tourism destinations. It emphasizes territorial sensitivity, place-based diagnosis, stakeholder participation, and the alignment of tourism activities with ecosystem preservation and community well-being.

This proposal also draws partial inspiration from the European Commission’s Blue Growth strategy (European Commission, 2012), which promotes a holistic vision of sustainable development in marine and maritime sectors. However, it should be noted that there are critical voices that point out that this strategy is still anchored in a neoliberal logic focused on economic productivity and sectoral growth, often neglecting community participation, cultural heritage, and environmental limits (Ehlers, 2016; Kyriazi et al., 2023).

In view of the above, this approach offers a conceptual and methodological framework that addresses the strategic vacuum in current coastal tourism management. It positions tourism not merely as an economic activity but as a vector for ecological responsibility, cultural revitalization, and adaptive governance, aligning destination promotion with the long-term sustainability of coastal ecosystems and communities.

To that end, and considering the objectives of the present study, Blue Marketing is defined as a tourism planning and management strategy specifically oriented towards marine-coastal areas, which adapts the principles of socio-environmental marketing to vulnerable territorial contexts. This approach integrates environmental awareness, sustainable tourism promotion, and cultural valorization into a place-based approach that seeks to balance local economic development with the conservation of coastal ecosystems. Its fundamental purpose is to design and communicate tourism products compatible with environmental preservation and coastal cultural identity, fostering participatory governance and shared responsibility among the different stakeholders involved in the destination.

While the principles of this coastal-oriented strategy could inspire initiatives in inland territories associated with aquatic ecosystems, its conceptual core is deeply rooted in the specific challenges and opportunities of marine-coastal environments, where land and sea interactions define ecological and cultural dynamics. Consequently, this emerging paradigm addresses a niche that is not fully covered by existing sustainable or territorial marketing approaches.

3. Materials and Methods

This study adopts a conceptual-applied methodological approach, whose main objective is the formulation of a normative ten-step guide for the implementation of sustainable tourism marketing strategies in coastal contexts. Unlike empirical studies based exclusively on quantitative or qualitative methods, this work is framed within the tradition of research oriented towards the design of operational frameworks for action (design-oriented research), combining theoretical review, territorial analysis, and normative synthesis. The methodological process was developed in three complementary phases: Data sources and territorial diagnosis, selection of case study, and strategic construction of the decalogue.

3.1. Data Sources and Territorial Diagnosis

Firstly, a critical review of specialized literature on coastal tourism, sustainable marketing, ICZM, and territorial governance models was carried out. This review made it possible to identify both the existing gaps in the literature—particularly in relation to the lack of specific marketing frameworks adapted to marine-coastal environments—and the principles already consolidated in other disciplines; such as the decalogue of coastal governance proposed by Barragán Muñoz (2003, 2014).

Secondly, the territorial diagnosis was constructed through the integration of multiple data sources:

- (1)

- Geographic Information Systems (GIS): A cartographic database was developed to integrate land use, protected areas, accessibility networks, and coastal morphological features. Additionally, a georeferenced inventory of cultural and natural heritage assets was compiled to identify areas of symbolic, historical, and tourism relevance. This inventory includes archaeological sites, architectural landmarks, ethnological features, hydraulic works, hospitality-related heritage, and elements of cultural landscape—such as traditional roads or livestock trails—mapped using official spatial data from regional and national institutions. Layers corresponding to public domain zones (e.g., roads, coastlines, easements) were also integrated to assess legal and planning constraints. Together, these spatial layers enabled the detection of priority areas for intervention, misalignments between resources and planning tools, and opportunities for the development of low-impact, identity-based tourism strategies.Spatial data were cross-validated through cartographic triangulation and comparison with secondary sources to ensure analytical reliability. The validation criteria included (i) temporal coherence—only data from the last 5–10 years were used; (ii) adequate spatial resolution (minimum 1:25,000); and (iii) thematic relevance to tourism–environment interactions in coastal zones. These parameters ensured that the spatial analysis reflected current territorial dynamics and supported accurate diagnosis.

- (2)

- A comprehensive review was carried out of strategic and normative planning instruments, including local tourism strategies, general urban development plans (PGOU), and coastal management schemes. These documents, sourced primarily from the municipalities of Barbate and Vejer de la Frontera, the Diputación de Cádiz, and the Andalusian Regional Government, were examined to assess the degree of integration between tourism communication, land use regulation, and sustainability objectives. Special attention was paid to mismatches between the presence of high-value resources and their visibility or treatment in planning instruments.

- (3)

- Fieldwork conducted between 2023 and 2024 under the COSTURA research project involved multiple visits to the area, combining direct observations with informal conversations with local actors. Observations focused on the state of tourism infrastructure (e.g., signage, trails, viewpoints), use patterns along the coastline, conservation issues, and the visibility of cultural and natural assets. The ground-truthing process was instrumental in identifying discrepancies between official discourses and actual conditions—particularly regarding signage quality; neglected heritage sites; and the physical accessibility of natural landscapes.

3.2. Case Selection: Barbate and Vejer

The case study focuses on the coastal corridor formed by the municipalities of Barbate and Vejer de la Frontera, located in the province of Cádiz (Spain). The selection of this area responds to a combination of ecological, cultural, and planning factors that make it particularly suitable for the application of the Blue Marketing framework.

First, the area presents a high level of ecological sensitivity. Both municipalities encompass or are adjacent to protected natural areas, including La Breña y Marismas del Barbate Natural Park and the La Janda wetland. These ecosystems are recognized for their biodiversity, fragility, and the environmental pressures they face due to tourism, land-use changes, and climate change. The presence of Special Areas of Conservation (SACs) within the Natura 2000 network reinforces the need for strategic approaches that integrate conservation priorities into tourism planning and communication.

Second, the corridor represents a context of tourism relevance and dynamism. It combines strong high-season tourism flows—particularly in Barbate—with an emerging profile of cultural and ecological tourism linked to local identity; natural landscapes; and gastronomic heritage.

Third, the territory possesses a rich cultural heritage rooted in maritime traditions, local gastronomy (such as almadraba tuna fishing), and a unique combination of coastal and inland landscapes. This heritage is reflected in both tangible and intangible forms—defensive architecture; ethnographic features; rural pathways; and fishing practices—which contribute to the area’s symbolic value and its potential for identity-based tourism promotion.

Fourth, the area shows clear territorial contrasts that reinforce the strategic value of the case. Barbate, located directly on the coast, has historically been subject to more intense tourism development and environmental pressures, while Vejer—although slightly inland—is closely linked to the same functional tourism system. Vejer offers a different profile, with a strong emphasis on cultural tourism, heritage preservation, and scenic urbanism, representing an alternative model of tourism articulation.

This combination of ecological vulnerability, tourism dynamics, cultural distinctiveness, and territorial diversity makes the Barbate–Vejer corridor a paradigmatic case study for testing and refining the Blue Marketing framework. Moreover, the characteristics of the area enhance the transferability and scalability of the proposed decalogue, making it applicable to other coastal territories facing similar socio-environmental tensions.

3.3. Construction of the Blue Marketing Decalogue (BMD)

The decalogue was elaborated through a three-phase process: (1) Theoretical synthesis: Key concepts from ICZM, sustainable marketing, and cultural tourism were systematized to define the conceptual pillars of Blue Marketing; (2) territorial diagnosis: A problem-potential matrix was developed for the Barbate-Vejer area, identifying key sustainability issues; and (3) strategic translation: Each principle of the decalogue was derived by aligning diagnostic findings with theoretical insights, ensuring relevance, coherence, and applicability to tourism planning and communication. The resulting ten principles were then grouped into three thematic blocks—ecosystem-focused sustainability; cultural identity and territorial singularity; and strategic planning and adaptive governance—to reflect the multidimensional nature of Blue Marketing and facilitate their integration into planning and policy instruments. This classification was guided by the structural problems identified in the diagnosis (ecological disconnection, cultural homogenization, and planning incoherence) and seeks to bridge key gaps between sustainability theory, territorial realities, and tourism strategies.

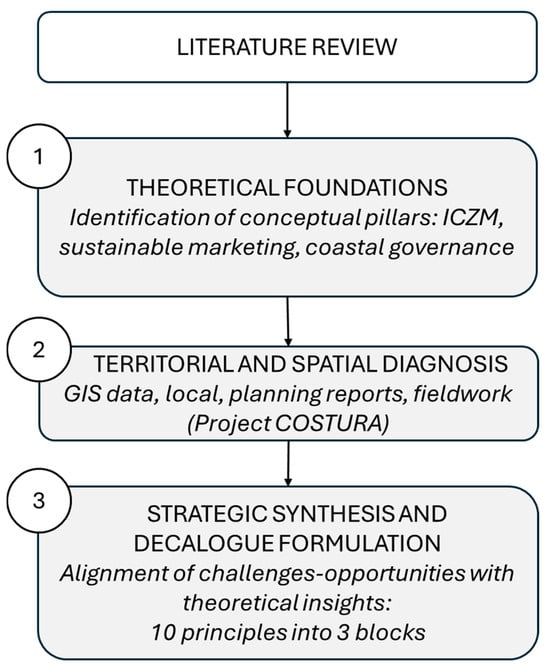

The following figure graphically synthesizes the logical flow from theory to diagnosis to strategy (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Methodological framework for the construction of the Blue Marketing Decalogue (BMD), integrating theory, territorial analysis, and strategic synthesis.

This three-phase process provided the analytical and conceptual structure needed to articulate a coherent set of marketing principles tailored to the specific challenges and opportunities observed in the Barbate–Vejer coastal system.

4. Results

The results of this study are organized to provide empirical and strategic foundations that support the formulation of the Blue Marketing Decalogue (hereinafter BMD). Rather than offering a full application of an operational model, this section presents the key insights derived from the territorial analysis of the Barbate–Vejer coastal corridor, which serves as a reference case for identifying patterns, needs, and strategic opportunities relevant to sustainable tourism management in coastal environments. The findings are structured in three parts: First, the territorial diagnosis is summarized, highlighting the ecological and cultural values as well as the tourism-related pressures affecting the area; second, the main strategic axes emerging from the diagnosis are outlined; and finally, the implications of these results for the construction of the BMD are discussed.

4.1. Territorial Diagnosis of Barbate-Vejer

The area under analysis is located between the municipalities of Barbate and Vejer de la Frontera, on the Atlantic coast of the province of Cádiz (Spain). This coastal space is characterized by its remarkable ecological, cultural, and landscape richness, including high-value environmental units such as the La Breña y Marismas del Barbate Natural Park and the Tombolo of Trafalgar Natural Monument (Figure 2). The selection of this area is based on its dual status as a consolidated tourism destination and a zone under increasing environmental pressure, making it an ideal space for the application of strategies based on the Blue Marketing approach.

Figure 2.

Location of the case study.

From a territorial diagnostic perspective, the area features an undulating relief and a dense network of rural and coastal paths that link different landscape components, allowing for sustainable mobility modes such as hiking and cycling. In contrast to other more urbanized and saturated coastal areas of Andalusia, this coastal corridor maintains a high degree of conservation in its natural and cultural values and local identity.

From an ecological perspective, the Barbate-Vejer territory includes a mosaic of coastal habitats with high environmental value, many of which are protected under the Natura 2000 network as Special Areas of Conservation (SACs). These encompass Mediterranean pine forests, wetlands, dunes, coastal cliffs, and halophytic ecosystems, especially within the more than 5000 hectares of the La Breña y Marismas del Barbate Natural Park (Figure 3). This area supports migratory bird populations and endemic flora, with relatively low levels of anthropogenic disturbance in core zones.

Figure 3.

Spatial distribution of protected natural areas and planning instruments in the Barbate–Vejer coastal system. Source: Authors.

The distribution and ecological richness of these habitats underscore the potential for low-impact tourism initiatives focused on biodiversity conservation and environmental education. However, the area faces growing threats from uncontrolled visitor flows, land-use conflicts, unauthorized camping, and coastal erosion, all exacerbated by the absence of an integrated tourism management strategy, which undermines the long-term effectiveness of existing conservation measures.

According to the Spanish National Institute of Statistics, Barbate has 22,725 inhabitants and Vejer de la Frontera 13,041, both with seasonal population increases during summer months due to high tourist demand (INE, 2025). Andalusia received over 36 million international tourists in 2024, exceeding pre-pandemic levels and confirming the persistent concentration of tourism flows along the Atlantic and Mediterranean coasts (Junta de Andalucía, 2024).

In terms of tourism, this sector represents a backbone of economic activity in both municipalities, generating substantial direct and indirect employment. In the province of Cádiz—which includes Barbate and Vejer—tourism achieved over 8.4 million hotel overnight stays in 2024, marking a new all-time high and representing a 4.3% increase from 2023 (INE, 2024). Despite this performance, employment remains seasonal and often precarious, with spikes during summer followed by low activity levels in off-peak months. According to the 2024 municipal census, Barbate-Vejer recorded 16,120 hotel bed places—an indicator of significant tourist accommodation capacity—and employment in these services fluctuates heavily throughout the year (SIMA, 2024). These factors reinforce the urgency of implementing tourism models aligned with stable job creation, biodiversity conservation, and strengthening of local identity—goals foundational to the Blue Marketing framework.

From a cultural heritage perspective, the inventory identifies key elements such as historical defense towers (e.g., Torre del Tajo), traditional fishing infrastructures (almadraba sites) (Figure 4a,b), rural agrarian landscapes, and historical urban nuclei with Islamic and medieval origins, such as Vejer de la Frontera’s old town.

Figure 4.

(a) Traditional tuna fishing (almadraba) as an example of maritime cultural heritage. (b) Coastal cliffs and Torre del Tajo, a historic watchtower overlooking the Barbate coast, as a symbol of the cultural and scenic landscape.

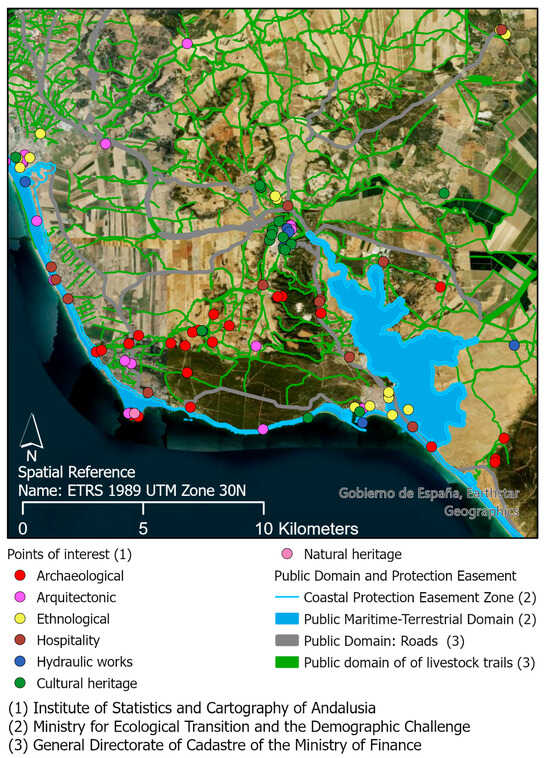

These elements form a network of cultural landmarks that are spatially associated with natural routes and coastal viewpoints, reinforcing the potential for integrated eco-cultural tourism experiences (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Territorial distribution of cultural assets, tourism services, and coastal public domain in the Barbate–Vejer corridor. Source: Authors.

The spatial analysis conducted using Geographic Information Systems (GIS) enabled the overlay of layers containing topographic, cultural, infrastructural, and environmental data. This allowed for a comprehensive visualization of the territory, identifying both opportunities and constraints for tourism development. The analysis revealed that natural and cultural resources are not uniformly distributed but rather tend to cluster in specific areas where the combination of landscape values, biodiversity, and cultural authenticity is particularly strong. This pattern allows for the design of thematic itineraries that can target different market segments, such as eco-tourists, cultural tourists, and experiential travelers.

Furthermore, the analysis of accessibility patterns shows that many of these key resources are connected through existing rural tracks and coastal trails, providing a viable infrastructure for the development of soft mobility tourism products (hiking, cycling, birdwatching). This facilitates the structuring of sustainable tourism circuits without the need for major new infrastructures, aligning with conservation objectives and enhancing the interpretative value of the landscape.

From an environmental perspective, the clearly coastal character of the territory reinforces its complexity as a planning space. The continuous interaction between marine and terrestrial systems generates a diversity of highly sensitive habitats—such as marshes; dunes; cliffs; and sandy beaches—that are subject to increasing pressures from seasonal tourism. This coastal condition not only shapes the spatial distribution of resources but also determines their vulnerability to climate change, particularly in terms of coastal erosion, salinization, and habitat loss. At the same time, the cultural identity of the area is closely tied to the sea, as evidenced by its fishing traditions, historical defensive structures against maritime incursions, and productive uses such as saltworks and almadraba tuna fishing. Altogether, this is a territory whose tourism planning requires the integration of specific criteria for sustainable coastal management, thus fully justifying the creation of normative planning tools adapted to these realities.

Overall, the inventory and spatial analysis confirm that the Barbate–Vejer coastal corridor possesses a rich and diversified resource base that, if properly valorized and communicated, can support the development of a responsible tourism model grounded in environmental conservation, cultural reinforcement, and destination competitiveness.

4.2. A Strategy Framework: The Blue Marketing Decalogue

The diagnostic work carried out in the Barbate–Vejer corridor reveals challenges that are not exclusive to this case but rather symptomatic of broader tensions documented in the academic literature on coastal tourism management and planning.

Firstly, a persistent disconnection between tourism marketing and the ecological reality of coastal environments can be observed. Promotional narratives often present these destinations as limitless spaces for leisure consumption, obscuring their ecological fragility and masking the pressures they endure due to urbanization, seasonal overcrowding, and climate vulnerability (Dodds & Holmes, 2018). The diagnosis in the Barbate–Vejer area reflects this tension: while its natural values are exceptional, tourism promotion continues to rely heavily on idealized imagery with little reference to environmental limits or conservation needs. This reflects a widespread absence of ecological awareness in tourism communication strategies, as noted by Hall (2011), who warns that marketing remains largely disconnected from the sustainability agendas of destination planning.

Secondly, there is an evident loss of identity and homogenization of tourism narratives, a phenomenon driven by the tendency to reproduce globalized, generic branding schemes. As highlighted by Hernández-Mogollón et al. (2018), many coastal destinations rely on stereotypical representations that dilute local culture and exclude community voices. The diagnosis of the study area confirms that symbolic elements such as traditional fishing, defensive maritime architecture, or agrarian landscapes are underrepresented or oversimplified in promotional content, undermining both authenticity and differentiation. This is consistent with the argument of Richards (2011), who emphasizes the need for place-based branding that is participatory and grounded in real cultural values.

Finally, the study confirms a lack of coherence between tourism promotion and territorial planning instruments. Although strategic tourism planning has evolved in many coastal contexts, marketing actions often remain disconnected from land use planning, protected area management, and broader sustainability goals. This incoherence can lead to overpromotion of vulnerable zones, duplication of efforts, or the neglect of strategic priorities identified in destination management plans. As suggested by Bramwell and Lane (2011), the integration of marketing within destination governance frameworks remains one of the most underdeveloped aspects of sustainable tourism, particularly in coastal environments with complex institutional and environmental dynamics.

To provide an operational response to these structural problems, a policy framework is proposed, structured around ten guiding principles organized into three strategic blocks: (1) Ecosystem-focused sustainability; (2) cultural identity and territorial singularity; and (3) strategic planning and adaptive governance. These principles are designed to guide the adaptation of tourism marketing to the ecological, cultural, and planning dimensions of coastal territories, but also to facilitate their implementation through strategic tools and concrete policies. The framework is visually synthesized in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Blue Marketing Decalogue (BMD): Strategic framework for sustainable tourism planning in coastal destinations. Source: Authors.

In response to the structural challenges identified in the previous section, this study proposes a normative framework composed of ten guiding principles, organized into three strategic blocks. While this framework has been conceptually developed through a comprehensive review of the academic literature, its practical configuration has been informed by the territorial diagnosis conducted in the Barbate–Vejer coastal corridor. This case study provided a grounded perspective on the misalignments commonly observed between tourism promotion, ecological sensitivity, and planning frameworks in coastal destinations.

The proposed framework is not intended to be prescriptive or context-specific; rather, it offers a flexible and transferable tool to support sustainable marketing strategies in diverse marine and coastal settings. Each of its principles addresses key dimensions of tourism communication—environmental; cultural; and governance-related—and can be implemented progressively; according to the institutional maturity and territorial characteristics of each destination.

The structure and content of the BMD are aligned with ongoing debates in the field of tourism studies. For instance, the need to reposition tourism marketing within broader destination governance frameworks has been underscored by authors such as Bramwell and Lane (2011), while Richards (2011) and Hernández-Mogollón et al. (2018) have called for more rooted, participatory narratives that reflect cultural specificity. Moreover, studies on climate vulnerability and sustainability in coastal tourism (e.g., Hall, 2011) emphasize the importance of integrating communication into the strategic planning of destinations.

The three strategic blocks and their corresponding principles are detailed below.

Block I. Ecosystem-focused sustainability: This first block responds to the increasing need for tourism marketing to support, rather than undermine, environmental preservation. Coastal ecosystems are particularly sensitive to the pressures generated by seasonal tourism and unregulated promotion. Numerous studies have emphasized the importance of integrating sustainability narratives into tourism marketing to ensure ecological resilience (Hall, 2011; Dodds & Holmes, 2018). The Barbate–Vejer corridor provided concrete insights into this challenge, with significant natural assets (e.g., protected areas under Natura 2000) often represented in promotional content without reference to their vulnerability or carrying capacity. Accordingly, the following framework principles are identified:

- Principle 1: Centrality of the coastal ecosystem. Tourism marketing should position the coastal ecosystem as a fundamental pillar of the destination’s identity and communication strategy, moving beyond scenic representation to acknowledge ecological complexity.

- Principle 2: Promotion of low-impact tourism products. Products such as interpretation trails, wildlife observation, or environmental education activities help reduce ecological footprint and create deeper connections between visitors and the natural environment.

- Principle 3: Communication for environmental awareness and stewardship. Marketing messages must actively promote responsible behavior, aligning with environmental education approaches (Mier-Terán Franco, 2004) and transforming communication into a tool for awareness and conservation.

Block II. Cultural identity and territorial uniqueness: The second block focuses on preserving the cultural distinctiveness of coastal destinations, counteracting the tendency of globalized tourism to erase local identities. Research by Richards (2011) and Hernández-Mogollón et al. (2018) has shown how generic branding strategies contribute to cultural homogenization and weaken destination authenticity. The principles identified under this block are

- Principle 4: Integration of cultural and natural heritage in the territorial narrative. Narratives should reflect the hybrid reality of coastal territories where landscape, memory, and cultural practices are interwoven (Timothy, 2024).

- Principle 5: Defense of authenticity and narrative rootedness. Communication should prioritize community-based narratives and lived experiences over generic promotional messages, enhancing the emotional and symbolic connection with place.

- Principle 6: Participatory construction of promotional discourse. Involving local stakeholders in tourism promotion ensures greater narrative legitimacy, reinforces identity, and promotes shared governance in tourism communication.

Block III. Strategic planning and adaptive governance: The final block promotes stronger integration between marketing and territorial planning. Authors such as Hall (2008) and Aman et al. (2024) highlight how the fragmentation between promotional and regulatory frameworks often leads to incoherent or unsustainable tourism development. This was evident in the study area, where promotional strategies were not always aligned with spatial planning tools or management frameworks of protected areas. The related principles are

- Principle 7: Territorial de-seasonalization and spatial rebalancing. Tourism marketing can be a key driver in mitigating seasonality and redirecting flows to less-visited areas, enhancing territorial cohesion (Ramírez-Guerrero et al., 2025).

- Principle 8: Integration of marketing with coastal and tourism planning. Communication must be based on strategic planning priorities and coordinated with local governance structures (Aman et al., 2024), ensuring long-term coherence and legitimacy.

- Principle 9: Measurability, transparency, and adaptive feedback. Incorporating indicators to monitor the impacts of marketing actions allows for real-time evaluation and continuous adaptation (UNEP & UNWTO, 2005).

- Principle 10: Ethical communication and coherence. Avoiding greenwashing, exaggeration, or misleading representations is essential to build trust among visitors and host communities, as recognized in ethical tourism charters and responsible communication literature.

- While some principles may appear conceptually adjacent—such as narrative authenticity and participatory storytelling—they represent distinct strategic emphases: the former concerns the truthful and culturally grounded content of messages, while the latter refers to the processes and actors involved in their creation and dissemination.

This normative framework offers ten interrelated principles organized into three strategic blocks that reflect the fundamental dimensions of coastal tourism sustainability: ecological preservation, cultural integrity, and adaptive governance. The Blue Marketing principles are intended to serve as a flexible tool that destinations can adapt and apply according to their territorial specificities, institutional contexts, and planning maturity. Their ultimate goal is to transform tourism marketing into a vector for sustainable development, rather than a mere promotional mechanism detached from territorial reality.

4.3. Strategic Translation of Blue Marketing Decalogue

To enable the practical application of the proposed normative framework, a set of strategic and normative instruments has been developed. These instruments are conceived not as prescriptive tools, but as adaptable and transferable mechanisms, capable of integrating into varying territorial conditions and governance systems.

Each principle is accompanied by preliminary indicators designed to support future monitoring and evaluation efforts. These indicators, although exploratory, aim to offer measurable criteria aligned with sustainability, governance, and cultural integrity.

Table 1 presents a synthesis matrix that links key theoretical foundations, diagnostic insights from the Barbate–Vejer case study, and the resulting normative principles of the Blue Marketing Decalogue. The matrix serves as a conceptual interface between the analytical stages of the research and the strategic proposals that follow, ensuring internal coherence, analytical transparency, and external applicability.

Table 1.

Analytical Matrix Linking Territorial Diagnosis of Barbate–Vejer with Normative Principles and Evaluation Metrics for Blue Marketing.

Although the Barbate–Vejer coastal territory is characterized by substantial ecological value and a rich cultural identity rooted in maritime traditions, the diagnostic perspective presented in the matrix intentionally foregrounds structural challenges. This emphasis does not imply a disregard for local assets but rather aims to expose the specific tensions, misalignments, and governance gaps that justify the need for a context-sensitive and sustainability-oriented approach such as Blue Marketing.

Each strategic block is associated with real or feasible examples that demonstrate its operational relevance in coastal tourism contexts:

- 1.

- Ecosystem-Focused Sustainability (Principles 1, 2, and 3):

This block encourages the alignment of tourism communication with coastal ecosystem preservation. Practical applications may include promotional campaigns that incorporate environmental sensitivity maps—highlighting protected zones and permitted activities—as seen in the Cabo de Gata Natural Park. Destinations could also redesign their promotional portfolios to emphasize low-impact products such as interpretive trails, environmental education experiences, or scientific tourism, similar to initiatives developed in the Atlantic Islands of Galicia. Additionally, conservation-oriented messages could be embedded in signage, mobile apps, or brochures, as demonstrated by Costa Rica’s “Responsible Tourism” program.

- 2.

- Cultural identity and territorial singularity (Principles 4, 5, and 6):

This strategic axis advocates for the valorization of cultural and landscape heritage as a means of differentiation and identity reinforcement. Application scenarios include the development of visual and textual narratives that feature cultural landscapes, artisanal knowledge, or maritime heritage—exemplified by Mallorca’s “Pesca-Turismo” initiative. Authenticity can also be reinforced through the use of local languages, symbols, and heritage elements in destination branding. Furthermore, participatory narratives may be co-created via community storytelling workshops, such as the “Storytelling Labs” promoted in certain UNESCO destinations.

- 3.

- Strategic Planning and Adaptive Governance (Principles 7, 8, 9, and 10):

These principles seek to embed marketing practices within integrated planning frameworks and transparent, adaptive governance. Potential applications include the development of Tourism Marketing Plans aligned with spatial planning instruments, such as Coastal Land Use Plans. Additionally, real-time monitoring systems using sustainability indicators—like those implemented by VisitScotland—can help assess the impact of promotional strategies. Ethical communication guidelines may be formalized through place-based charters and visual standards, audited to prevent greenwashing, as illustrated by New Zealand’s Tiaki Promise.

Building on these possible applications, the framework also incorporates a series of strategic and normative instruments that operationalize the decalogue and enhance its implementation in diverse territorial contexts.

On the strategic dimension, the proposed framework introduces instruments designed to foster alignment between tourism marketing and destination management objectives. These include Integrated Tourism Marketing Plans, coordinated with land-use and environmental planning tools (e.g., city planning or protected area management plans); participatory communication platforms that enable local stakeholders; and feedback systems supported by sustainability indicators to assess the real-time impact of promotional strategies (UNEP & UNWTO, 2005; Hall, 2011).

On the normative dimension, the framework incorporates tools that define ethical, narrative, and regulatory standards for tourism communication. These include Territorial and Ethical Communication Charters, which ensure coherence, place-based messaging, and the avoidance of greenwashing, as well as regulatory guidelines for embedding marketing within broader governance and sustainability frameworks. This approach aligns with ICZM principles as formulated by Barragán Muñoz (2003, 2014), particularly those related to institutional coordination, participatory governance, and the protection of coastal identity.

These strategic and normative instruments operationalize the principles articulated in the matrix, ensuring that each guideline is grounded in empirical diagnosis and supported by theoretical coherence. In doing so, they reinforce the Blue Marketing Decalogue (BMD) as a context-sensitive planning and communication tool, capable of responding to the specific vulnerabilities and opportunities of coastal destinations.

By translating territorial knowledge into actionable marketing strategies, the BMD enables destinations to align their communication efforts with sustainability imperatives, governance structures, and cultural integrity.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

This article proposes a strategic framework for the application of Blue Marketing in coastal tourism destinations. The resulting Blue Marketing Decalogue (BMD) is grounded in real territorial dynamics and enriched through the empirical analysis of the Barbate–Vejer coastal corridor. While the framework is universally transferable to other coastal contexts, the case study served as a practical foundation to articulate, refine, and validate the ten guiding principles.

The achievement of the specific objectives is confirmed through the formulation of a structured proposal that combines theoretical rigor with applied territorial analysis. First, the research introduces a novel conceptualization of marketing in coastal settings, establishing Blue Marketing as a transdisciplinary and context-sensitive strategy that balances environmental conservation, cultural identity, and destination governance. Second, the study identifies core structural challenges commonly observed in coastal tourism planning—such as ecological fragility; cultural homogenization; and institutional disconnection between marketing and territorial governance—and addresses them through three strategic blocks: Ecosystem-centered sustainability, cultural and identity-based communication, and planning-aligned governance. Third, the creation of the BMD itself fulfills the article’s normative ambition, offering a clear, flexible, and actionable framework for local administrations, tourism managers, and coastal planners.

The integration of real-world diagnosis—including spatial analysis; inventory of resources; and governance gaps—supports the principles outlined in the BMD. For instance, the emphasis on low-impact tourism products and soft mobility is informed by the ecological sensitivity and trail networks of the study area. Similarly, the need to co-create narratives and defend local identity is rooted in the spatial and cultural richness observed across the Barbate–Vejer corridor. Moreover, the spatial concentration of natural and cultural resources—particularly in areas where biodiversity overlaps with strong local identity—suggests the need for zoning strategies that prioritize these high-value nodes for sustainable tourism development. Such areas could serve as pilot zones for implementing soft mobility, environmental education programs, and participatory branding initiatives, thereby maximizing impact while minimizing ecological disruption. This territorial clustering reinforces the strategic relevance of Blue Marketing as a tool to support place-based prioritization and adaptive tourism planning.

Nevertheless, the application of the BMD in real-world contexts is not without limitations. Many coastal destinations face structural constraints, such as limited financial and technical resources, lack of specialized personnel, and competing political agendas that may obstruct long-term planning efforts. In addition, the risk of institutional greenwashing—where sustainability is invoked rhetorically but not implemented—remains a concern; particularly when communication strategies are not tied to verifiable indicators or participatory governance.

This framework aligns with the academic literature advocating for planning models that integrate sustainability and local engagement (Hall, 2011; Peattie, 2001; Mier-Terán Franco, 2004). It also responds to calls for tourism marketing to move beyond promotion, adopting roles in education, regulation, and governance. In addressing RQ1, the BMD articulates a set of normative principles that embed sustainability, cultural identity, and governance into tourism communication in a coherent and structured manner. Through RQ2, the use of a territorial case study not only grounded these principles in empirical evidence but also demonstrated their analytical and strategic value across different planning dimensions. While the Barbate–Vejer corridor served as the testing ground, the principles maintain a high degree of transferability to other coastal contexts with similar socio-ecological tensions. Finally, in relation to RQ3, the study highlights the mediating role that marketing can play between environmental planning, cultural expression, and destination competitiveness, proposing it as a strategic hinge capable of articulating identity, guiding tourist behavior, and aligning communication with long-term sustainability objectives.

It is essential to acknowledge that marketing alone cannot overcome structural issues of territorial governance or economic dependency. Its contribution lies primarily in acting as a mediating tool—supporting coherence between planning and communication; amplifying community voices; and framing sustainability in a compelling and contextually relevant way. These strengths, while valuable, are contingent on broader institutional frameworks and political will.

It is important to clarify that the aim of this article is not to introduce a new discipline, but rather to advance a renewed strategic and conceptual approach. Blue Marketing is conceived as a contextual adaptation that recognizes the specific challenges and opportunities of coastal destinations. Its objective is to reinterpret and apply established marketing principles through the lens of territorial sensitivity, ecological vulnerability, and community-based governance—thereby contributing to a more integrated and sustainability-oriented vision for tourism communication and planning.

Nonetheless, a critical reflection is warranted regarding the ideological underpinnings of marketing itself. While the BMD reframes marketing as a mediating function aligned with territorial values and sustainability goals, it still operates within market-driven logics. In neoliberal tourism economies, there is a risk that even well-intentioned strategies may inadvertently commodify cultural and ecological assets. The promotion of authenticity or biodiversity, for instance, can be co-opted as aesthetic or symbolic capital rather than fostering genuine systemic change. Therefore, the potential of Blue Marketing should be understood not as a neutral tool but as a contested space—where ethical tensions; power relations; and market imperatives intersect. This underscores the importance of governance safeguards, participatory checks, and critical evaluation frameworks to ensure that the values promoted are not diluted or instrumentalized.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

The introduction of Blue Marketing as a conceptual and strategic framework in this study contributes to redefining the role of tourism marketing within coastal planning. Traditionally, tourism marketing has been associated with promotional and competitive positioning goals, often disconnected from environmental and cultural realities. In contrast, this article advances a broader theoretical vision in which marketing is framed as a mediating and integrative function, capable of aligning territorial identity, ecological sustainability, and destination governance.

This approach contributes to ongoing academic debates in tourism and environmental planning, particularly those addressing the fragmentation between promotional discourses and territorial regulation (Sobhani et al., 2023). By positioning the coastal ecosystem and cultural heritage as central narrative pillars, Blue Marketing adds symbolic and strategic value to local assets, reinforcing their protection through storytelling. Moreover, this aligns with the broader movement toward place-based marketing and post-disciplinary tourism models, where communication, governance, and planning intersect (Richards, 2011; Hernández-Mogollón et al., 2018).

The theoretical premises of Blue Marketing also intersect with cultural sustainability frameworks proposed by Duxbury and Campbell. These authors have advanced the notion that sustainable tourism requires deep-rooted collaboration between communities, institutions, and cultural agents—moving beyond heritage commodification towards regenerative cultural economies (Duxbury & Campbell, 2011; Duxbury et al., 2025). This reinforces the potential of Blue Marketing as a planning tool, but also as a driver of local capacity-building and cultural empowerment, particularly in smaller or peripheral communities where tourism is both an opportunity and a risk.

In addition, the proposed BMD introduces a structured but adaptable typology of principles, filling a gap in the literature regarding normative guidance for coastal marketing strategies. Unlike purely promotional frameworks, Blue Marketing incorporates ethical standards, participatory narratives, and impact assessment mechanisms—features more commonly associated with environmental or planning literature (Bramwell & Lane, 2011; UNEP & UNWTO, 2005).

Finally, the framework reinforces the connection between Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM) and tourism development, a relationship that remains underexplored in much of the existing literature (Barragán Muñoz, 2003, 2014). By translating ICZM values—such as participation; identity; and adaptive management—into marketing language and strategy; the BMD offers a cross-disciplinary contribution with the potential to inspire further conceptual innovation in the governance of coastal tourism.

The study contributes a novel conceptualization of the marketing-territory relationship, emphasizing that marketing strategies should not only seek to attract visitors but also promote conservation values and reinforce the authentic identity of the destination, in contrast to traditional promotional approaches focused solely on economic growth.

5.2. Practical Implications

From an operational standpoint, the BMD provides local authorities, tourism boards, and destination managers with a pragmatic roadmap to integrate communication strategies into sustainability objectives. In contexts marked by seasonal saturation, ecological sensitivity, or cultural dilution—common challenges in coastal destinations—the BMD offers criteria for decision-making that balance visibility with responsibility.

Each of the ten principles can be translated into concrete actions. For example, the promotion of low-impact tourism products (Principle 2) encourages municipalities to prioritize hiking routes, birdwatching, or environmental interpretation over mass-consumption offers. The participatory construction of tourism narratives (Principle 6) can be operationalized through community storytelling workshops or collaborative branding strategies, ensuring that promotional content reflects local values and avoids stereotypical imagery.

In parallel, the implementation of the BMD can be significantly enhanced through the integration of digital technologies and innovative communication tools. Mobile applications, augmented reality (AR) experiences, and geolocated storytelling platforms offer opportunities to disseminate sustainable narratives in interactive and user-centered formats. For instance, AR-enhanced interpretive trails or app-based audio guides can reinforce principles such as environmental education, cultural authenticity, and soft mobility.

Likewise, community-managed digital platforms can facilitate participatory content creation, local storytelling, and peer-to-peer knowledge exchange. In terms of monitoring and governance, interactive dashboards based on AI-supported tourism analytics and sustainability indicators could support real-time evaluation of communication impacts, empowering destinations to adjust strategies dynamically. These technologies, if aligned with the BMDs normative principles, can serve as dissemination channels but also as tools of co-creation, accountability, and adaptive governance.

At the same time, normative instruments—such as ethical charters; narrative guidelines; or regulatory codes—offer governance frameworks to legitimize and supervise the implementation process. These tools can be adapted to varying levels of institutional complexity, making the framework suitable for both consolidated and emerging destinations.

Importantly, the BMD contributes to the professionalization and governance of tourism marketing, an area often left outside formal planning structures. By integrating impact monitoring mechanisms (e.g., sustainability indicators for promotional actions), the model allows for adaptive management, improving accountability and long-term alignment with environmental and cultural objectives.

Finally, the application of Blue Marketing allows destinations to reposition their value proposition in highly competitive markets—not by promoting volume; but by enhancing identity; authenticity; and ecological coherence. This strategic repositioning strengthens territorial resilience, diversifies the tourism offer, and builds stronger connections between visitors and places.

Nonetheless, its successful implementation is not exempt from limitations. Institutional constraints—such as limited technical capacity; budgetary restrictions; or political volatility—can hinder the effective application of the BMD in certain coastal settings. Risks of symbolic participation also persist, especially when participatory tools are adopted superficially without influencing decision-making. Similarly, the instrumentalization of sustainability discourses for reputational purposes (i.e., greenwashing) may dilute the framework’s transformative potential if not properly regulated.

To mitigate these challenges and support real-world application, a preliminary implementation roadmap is proposed. Key instruments include Integrated Tourism Marketing Plans (ITMPs) aligned with land-use and environmental strategies, participatory communication platforms that engage local actors in co-creating narratives, and adaptive monitoring systems based on sustainability indicators. These tools provide structure and flexibility, allowing destinations to calibrate the framework according to their governance maturity and ecological specificities.

The BMDs architecture is intentionally open, enabling its transferability across different territorial and institutional contexts. While it is especially relevant for destinations with consolidated tourism flows and emerging sustainability agendas, it also holds promise for Global South regions—such as parts of Latin America—where ecological vulnerability; governance fragmentation; and cultural richness coexist. In these settings, Blue Marketing offers a strategic lens to integrate communication, identity, and sustainability into coherent and place-based tourism development strategies.

6. Limitations and Future Directions

The methodological framework ensures scientific validity through cross-analysis of diverse sources, a strong theoretical foundation, and explicit articulation of the diagnostic-strategic nexus. Despite its contributions, this study presents certain limitations. First, while the framework is informed by an in-depth territorial case, its generalization requires validation across other socio-ecological settings. Second, the approach remains expert-driven; future applications should include participatory processes that allow local stakeholders, communities, and tourism agents to contribute directly to the definition and implementation of marketing narratives and strategies. This would enhance the legitimacy, cultural depth, and long-term viability of Blue Marketing initiatives.

It is important to note that this study did not include direct input from local stakeholders through interviews, focus groups, or participatory workshops. This absence is due to the exploratory and theoretical nature of the research, which aimed primarily to develop a normative framework based on territorial diagnosis and literature review. However, the integration of local voices is recognized as a fundamental dimension of governance and cultural legitimacy in tourism planning. Therefore, future research should incorporate participatory methodologies to validate, enrich, and adapt the proposed principles from the perspective of local communities and tourism actors in each destination.

Future research should also explore how the BMD performs under different institutional, ecological, and market conditions and how it can be operationalized through performance indicators, regulatory mechanisms, and co-management frameworks. Furthermore, comparative studies across coastal regions would help refine the universal elements of the framework and identify context-specific adaptations. It is also important to emphasize the distinctive nature of coastal and marine destinations, which constitutes the conceptual foundation of the proposed approach. Unlike inland or urban tourism contexts, coastal territories are shaped by the continuous interaction between land and sea, giving rise to ecologically fragile and spatially dynamic systems. These areas are especially sensitive to overcrowding, climate-induced threats such as erosion and salinization, and the loss of biodiversity.

These specificities reinforce the need for planning and communication strategies that are not only sensitive to ecological and cultural particularities but also capable of articulating tourism development with long-term territorial resilience. In this regard, Blue Marketing should not be viewed as a generic solution but as a targeted contribution to the ongoing redefinition of coastal tourism management in the face of growing environmental and social complexity.

In terms of validation, future work could consider the design of pilot initiatives to test the operational viability of the BMD in real coastal planning processes. Alternatively, a Delphi study involving experts, public officials, and destination managers could help refine the decalogue’s structure, feasibility, and perceived value. These complementary approaches would strengthen the methodological robustness of the model and provide a stronger foundation for institutional adoption.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.R.-G. and M.A.-G.; methodology, G.R.-G.; software, A.F.-E.; validation, J.A.C.-R., A.F.-E., and G.R.-G.; formal analysis, G.R.-G. and M.A.-G.; investigation, J.A.C.-R.; resources, J.A.C.-R.; data curation, A.F.-E.; writing—original draft preparation, G.R.-G.; writing—review and editing, G.R.-G., J.A.C.-R., A.F.-E., and M.A.-G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the COSTURA project, co-funded by the Regional Ministry of University, Research, and Innovation of the Government of Andalusia and by the European Union through the Next Generation EU funds of the Recovery, Transformation, and Resilience Plan under grant agreement PCM_00040.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ICZM | Integrated Coastal Zones Management |

| BMD | Blue Marketing Decalogue |

References

- Ajuhari, Z., Aziz, A., Yaakob, S. S. N., Abu Bakar, S., & Mariapan, M. (2023). Systematic literature review on methods of assessing carrying capacity in recreation and tourism destinations. Sustainability, 15(4), 3474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aman, E. E., Papp-Váry, Á. F., Kangai, D., & Odunga, S. O. (2024). Building a sustainable future: Challenges, opportunities, and innovative strategies for destination branding in tourism. Administrative Sciences, 14(12), 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arisci, A., De Waele, J., Di Gregorio, F., Ferrucci, I., & Follesa, R. (2003). Geoenvironmental analysis in coastal zone management: A case study in Southwest-Sardinia (Italy). Journal of Coastal Research, 19, 963–970. [Google Scholar]

- Baloch, Q., Shah, S., Iqbal, N., Sheeraz, M., AsadUllah, M., Mahar, S., & Khan, A. (2022). Impact of tourism development upon environmental sustainability: A suggested framework for sustainable ecotourism. Environmental Science and Pollution Research International, 30, 5917–5930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barragán Muñoz, J. M. (2003). Propuesta de base metodológica para la gestión integrada de zonas costeras en Iberoamérica [Doctoral dissertation, Universidad de Cádiz]. [Google Scholar]

- Barragán Muñoz, J. M. (2014). Política, gestión y litoral: Nueva visión de la gestión integrada de áreas litorales. Tebar. [Google Scholar]

- Barragán Muñoz, J. M., García Sanabria, J., & de Andrés García, M. (2020). ICZM strategy for the socioecological system of the Mar Menor (Spain): Methodological aspects and public participation. In Socio-ecological studies in natural protected areas: Linking community development and conservation in Mexico (pp. 243–272). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Biddulph, R. (2020). Tourism and Southeast Asian rural livelihood trajectories: The case of a large work integration social enterprise in Siem Reap, Cambodia. Journal of Qualitative Research in Tourism, 1(1), 73–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramwell, B., & Lane, B. (2011). Critical research on the governance of tourism and sustainability. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 19(4–5), 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R. (1991). Tourism, environment, and sustainable development. Environmental Conservation, 18, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Andrés García, M., & Barragán Muñoz, J. M. (2020). La gestión de áreas litorales en España y Latinoamerica, II. Universidad de Cádiz. [Google Scholar]

- Dodds, R., & Holmes, M. (2018). Is coastal tourism sustainable? Social and ecological implications. Journal of Coastal Research, 85(Suppl. 1), 1406–1410. [Google Scholar]

- Duxbury, N., & Campbell, H. (2011). Developing and revitalizing rural communities through arts and culture. Small Cities Imprint, 3(1), 111–122. [Google Scholar]

- Duxbury, N., de Castro, T. V., & Silva, S. (2025). Culture–tourism entanglements: Moving from grassroots practices to regenerative cultural policies in smaller communities. International Journal of Cultural Policy, 31(4), 497–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehlers, P. (2016). Blue growth and ocean governance—How to balance the use and the protection of the seas. WMU Journal of Maritime Affairs, 15(2), 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elorrieta, B., Cerdan Schwitzguébel, A., & Torres-Delgado, A. (2022). From success to unrest: The social impacts of tourism in Barcelona. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 8(3), 675–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. (2012). Blue growth: Opportunities for marine and maritime sustainable growth (COM(2012) 494 final). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2012:0494:FIN:EN:PDF (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- Fabinyi, M., Belton, B., Dressler, W. H., Knudsen, M., Adhuri, D. S., Aziz, A. A., Akber, M. A., Kittitornkool, J., Kongkaew, C., Marschke, M., & Pido, M. (2022). Coastal transitions: Small-scale fisheries, livelihoods, and maritime zone developments in Southeast Asia. Journal of Rural Studies, 91, 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griggs, D., Stafford-Smith, M., Gaffney, O., Rockström, J., Öhman, M. C., Shyamsundar, P., Steffen, W., Glaser, G., Kanie, N., & Noble, I. (2013). Sustainable development goals for people and planet. Nature, 495(7441), 305–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gryshchenko, O., Babenko, V., Bilovodska, O., Voronkova, T., Ponomarenko, I., & Shatskaya, Z. (2022). Green tourism business as marketing perspective in environmental management. Global Journal of Environmental Science and Management, 8(1), 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C. M. (2008). Tourism planning: Policies, processes and relationships. Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C. M. (2011). Policy learning and policy failure in sustainable tourism governance: From first-and second-order to third-order change? Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 19(4–5), 649–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X., Ye, C., Huang, S., & Su, L. (2024). The “green persuasion effect” of negative messages: How and when message framing influences tourists’ environmentally responsible behavior. Journal of Travel Research. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Mogollón, J. M., Duarte, A. M., & Folgado-Fernández, J. A. (2018). Cultural heritage and urban tourism: Historic city branding in Spain. Cities, 78, 111–120. [Google Scholar]

- Iamkovaia, M., Arcila Garrido, M., Cardoso Martins, F., Izquierdo González, A., & Vallejo Fernández de la Reguera, I. (2020). Analysis and comparison of tourism competitiveness in Spanish coastal areas. Journal of Regional Research, 2(47), 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística. (2024). Viajeros y pernoctaciones por comunidades autónomas y provincias de 2024. Available online: https://www.ine.es/dynt3/inebase/es/index.htm?padre=238&dh=1 (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística. (2025). Censo Anual de Población 2025. Available online: https://www.ine.es/dyngs/INEbase/operacion.htm?c=Estadistica_C&cid=1254736176992&menu=ultiDatos&idp=1254735572981 (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Junta de Andalucía. (2024). Encuesta de Coyuntura Turística de Andalucía. Data 2024. Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/institutodeestadisticaycartografia/dega/encuesta-de-coyuntura-turistica-de-andalucia-ecta (accessed on 14 June 2025).

- Kotler, P., & Lee, N. (2005a). Best of breed: When it Comes to gaining a market edge while supporting a social cause, “corporate social marketing” leads the pack. Social Marketing Quarterly, 11(3–4), 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P., & Lee, N. (2005b). Corporate social responsibility: Doing the most good for your company and your cause. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]