Metaverse Tourism: An Overview of Early Adopters’ Drivers and Anticipated Value for End-Users

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Background

2.2. Metaverse-Based Cases

2.3. NFT-Based Cases

2.4. Tourism-Complementary Cases

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

5. Discussion

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| UTAUT Construct | Associated Motives | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Performance Expectancy | Promotion, revenue stream, enrich services, distribution channel, reduce costs | Expected benefits for the organization |

| Effort Expectancy | Educational tool, rewards program, community building, collect feedback | Making operations easier |

| Social Influence | Being relevant, empower workforce, encourage co-creation, improve residents’ life, replace website, Reduce environmental impact, enhance guest/hospitality student experience, positioning, | Staying competitive and responsible |

| Facilitating Conditions | Smart city project, crowdfunding channel | Infrastructure support |

| TAM Construct | Associated Benefits for End-Users | Comments |

| Perceived Ease of Use | Workplace, real-world rewards/privileges, share feedback, education/training | Focus on usability, convenience, and practical value, making the technology more accessible and engaging |

| Perceived Usefulness | Entertainment, socialization, enhanced experience, source of information, help with decision-making, escapism, personalization, reduce costs, profit generation, feeling of co-creation, motivational environment, privacy | Focus on metaverse’s potential to enhance the tourism experience functionally, emotionally, and socially |

References

- Accenture. (2022). Why the Metaverse (really) matters for travel. Available online: https://www.accenture.com/us-en/blogs/compass-travel-blog/metaverse-travel (accessed on 26 October 2023).

- Accor. (2022). Leading the future of hospitality at accor: When innovation rhymes with next-generation. Available online: https://group.accor.com/en/Actualites/2022/07/students-innovation-challenges (accessed on 12 August 2023).

- Agnihotri, A., Bhattacharya, S., Sakka, G., & Vrontis, D. (2025). Driving metaverse adoption in the hospitality industry: An upper echelon perspective. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 37(4), 1199–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlgren, L. (2022). Try before you fly: Vueling Launches metaverse ticket sales experience. Available online: https://simpleflying.com/vueling-metaverse-ticket-sales (accessed on 12 September 2023).

- AIRSI. (2022). Welcome to the AIRSI 2022 metaverse. Available online: http://airsi2022.unizar.es/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Welcome-to-the-metaverse.pdf (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- Akyürek, S., Genç, G., Çalık, İ., & Şengel, Ü. (2024). Metaverse in tourism education: A mixed method on vision, challenges and extended technology acceptance model. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport & Tourism Education, 35, 100503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M. B., Tuhin, R., Alim, M. A., Rokonuzzaman, M., Rahman, S. M., & Nuruzzaman, M. (2024). Acceptance and use of ICT in tourism: The modified UTAUT model. Journal of Tourism Futures, 10(2), 334–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allam, Z., Sharifi, A., Bibri, S. E., Jones, D. S., & Krogstie, J. (2022). The Metaverse as a Virtual Form of Smart Cities: Opportunities and Challenges for Environmental, Economic, and Social Sustainability in Urban Futures. Smart Cities, 5(3), 771–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, J. (2022). Bengaluru airport’s T2 is up on metaverse. Available online: https://www.indiatoday.in/cryptocurrency/story/bengaluru-airports-t2-is-up-on-metaverse-2311725-2022-12-21 (accessed on 8 September 2023).

- Bae, S. Y., & Han, J. H. (2020). Considering cultural consonance in trustworthiness of online hotel reviews among generation Y for sustainable tourism: An extended TAM model. Sustainability, 12(7), 2942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, M. (2022). The metaverse. And how will it revolutionize everything. Liveright Publishing Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Barr, A. (2021). Marriott reveals NFTs as brand readies extended stay in metaverse. Available online: https://www.marketingdive.com/news/marriott-reveals-nfts-as-brand-readies-extended-stay-in-metaverse/611080/ (accessed on 9 September 2023).

- Barrera, K. G., & Shah, D. (2023). Marketing in the Metaverse: Conceptual understanding, framework, and research agenda. Journal of Business Research, 155, 113420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayram, A. (2021). Metaleisure: Leisure time habits to be changed with metaverse. Journal of Metaverse, 2(1), 1–7. Available online: https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/jmv/issue/67967/1065227.

- Benzies, K. M., Premji, S., Hayden, K. A., & Serrett, K. (2006). State-of-the-evidence reviews: Advantages and challenges of including grey literature. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing, 3(2), 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettati, A. (2023). Hotels in the 2023’s: Perspectives from Accor’s C-suite. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/travel-logistics-and-infrastructure/our-insights/hotels-in-the-2030s-perspectives-from-accors-c-suite (accessed on 12 August 2023).

- Bibri, S. E. (2022). The social shaping of the metaverse as an alternative to the imaginaries of data-driven smart cities: A study in science, technology, and society. Smart Cities, 5(3), 832–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgihan, A., Nusair, K., Okumus, F., & Cobanoglu, C. (2015). Applying flow theory to booking experiences: An integrated model in an online service context. Information & Management, 52(6), 668–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branding in Asia. (2022). Millennium hotels and resorts launches metaverse hotel—Msocial decentraland. Available online: https://www.brandinginasia.com/millennium-hotels-and-resorts-launches-metaverse-hotel-m-social-decentraland/ (accessed on 9 September 2023).

- Brouchoud, J. (2010). Construction of Aloft’s flagship hotels, first prototyped in second life, now complete. Available online: https://archvirtual.com/2010/06/24/construction-of-alofts-flagship-hotels-first-prototyped-in-second-life-now-complete/ (accessed on 9 September 2023).

- Buhalis, D., & Karatay, N. (2022). Mixed Reality (MR) for Generation Z in Cultural Heritage Tourism Towards Metaverse. In J. L. Stienmetz, B. Ferrer-Rosell, & D. Massimo (Eds.), Information and communication technologies in tourism 2022 (pp. 16–27). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D., & Law, R. (2008). Progress in information technology and tourism management: 20 years on and 10 years after the Internet—The state of eTourism research. Tourism Management, 29(4), 609–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D., Leung, D., & Lin, M. (2023). Metaverse as a disruptive technology revolutionising tourism management and marketing. Tourism Management, 97, 104724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D., Lin, M. S., & Leung, D. (2022). Metaverse as a driver for customer experience and value co-creation: Implications for hospitality and tourism management and marketing. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 35(2), 701–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caddeo, F., & Pinna, A. (2021). Opportunities and challenges of Blockchain-Oriented systems in the tourism industry. arXiv, arXiv:2107.06732. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, K. (2022). Metaverse and Hospitality: Everything you need to know. Available online: https://www.cvent.com/en/blog/hospitality/metaverse-hospitality (accessed on 11 September 2023).

- Chang, C. C. (2022). The role of individual factors in users’ intentions to use medical tourism mobile apps. Tourism and Hospitality, 3(4), 896–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CHANGI. (2023). Welcome to the ChangiVerse. Available online: https://www.changiairport.com/en/discover/changiverse.html (accessed on 20 September 2023).

- Chen, Z. (2023). Beyond reality: Examining the opportunities and challenges of cross-border integration between metaverse and hospitality industries. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 32, 967–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, Y. W., Susilo, W., Li, Y., Li, N., & Nguyen, C. (2023). Visualization and cybersecurity in the metaverse: A Survey. Journal of Imaging, 9(1), 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cobanoglu, C., Dogan, S., Berezina, K., & Collins, G. (2021). Hospitality and tourism information technology. USF M3 Publishing, LLC. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhelim, S., Kechadi, T., Chen, L., Aung, N., Ning, H., & Atzori, L. (2022). Edge-enabled Metaverse: The Convergence of Metaverse and Mobile Edge Computing. TechRxiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, H., Li, J., Fan, S., Lin, Z., Wu, X., & Cai, W. (2021, October 20–24). Metaverse for social good: A university campus prototype. Proceedings of the 29th ACM International Conference on Multimedia (pp. 153–161), Virtual. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, Y. K., Hughes, L., Baabdullah, A. M., Ribeiro-Navarrete, S., Giannakis, M., Al-Debei, M. M., Dennehy, D., Metri, B., Buhalis, D., Cheung, C. M. K., Conboy, K., Doyle, R., Dubey, R., Dutot, V., Felix, R., Goyal, D. P., Gustafsson, A., Hinsch, C., Jebabli, I., … Wamba, S. F. (2022). Metaverse beyond the hype: Multidisci-plinary perspectives on emerging challenges, opportunities, and agenda for research, practice and policy. International Journal of Information Management, 66, 102542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, Y. K., Hughes, L., Wang, Y., Alalwan, A. A., Ahn, S. J., Balakrishnan, J., Barta, S., Belk, R., Buhalis, D., Dutot, V., Felix, R., Filieri, R., Flavián, C., Gustafsson, A., Hinsch, C., Hollensen, S., Jain, V., Kim, J., Krishen, A. S., … Wirtz, J. (2023). Metaverse marketing: How the metaverse will shape the future of consumer research and practice. Psychology & Marketing, 40(4), 750–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Embling, D. (2023). How hotels are tapping into the potential of the metaverse to improve guest experiences. Available online: https://www.euronews.com/next/2023/06/22/how-hotels-are-tapping-into-the-potential-of-the-metaverse-to-improve-guest-experiences (accessed on 12 August 2023).

- Emirates. (2022). Emirates to launch NFTs and experiences in the metaverse. Available online: https://www.emirates.com/media-centre/emirates-to-launch-nfts-and-experiences-in-the-metaverse (accessed on 19 August 2023).

- Emirates. (2023). Game On! Emirates Group and AWS team up to craft an immersive digital world. Available online: https://www.emirates.com/media-centre/game-on-emirates-group-and-aws-team-up-to-craft-an-immersive-digital-world (accessed on 19 August 2023).

- Escobar, M. C. (2022a). Anantara Amsterdam adapts to a virtual future with RendezVerse. Available online: https://hospitalitytech.com/anantara-amsterdam-adapts-virtual-future-rendezverse (accessed on 5 September 2023).

- Escobar, M. C. (2022b). EV hotels partners with CDX to bring EV hotel to crypto markets around the world. Available online: https://hospitalitytech.com/ev-hotels-partners-cdx-bring-ev-hotel-crypto-markets-around-world (accessed on 3 October 2023).

- EV Hotel Corp. (2022). EV hotel, the first crypto and technology hotel brand, announces exclusive NFT membership rewards program. Available online: https://www.einnews.com/pr_news/564042304/ev-hotel-the-first-crypto-and-technology-hotel-brand-announces-exclusive-nft-membership-rewards-program (accessed on 2 October 2023).

- Fan, X., Jiang, X., & Deng, N. (2022). Immersive technology: A meta-analysis of augmented/virtual reality applications and their impact on tourism experience. Tourism Management, 91, 104534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazio, G., Fricano, S., Iannolino, S., & Pirrone, C. (2023). Metaverse and tourism development: Issues and opportunities in stakeholders’ perception. Information Technology & Tourism, 25(4), 507–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filimonau, V., Ashton, M., & Stankov, U. (2022). Virtual spaces as the future of consumption in tourism, hospitality and events. Journal of Tourism Futures, 10, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flavian, C., Ibanez-Sanchez, S., & Orus, C. (2019). Integrating virtual reality devices into the body: Effects of technological embodiment on customer engagement and behavioural intentions toward the destination. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 36(7), 847–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florido-Benítez, L. (2024). Metaverse cannot be an extra marketing immersive tool to increase sales in tourism cities. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 10(3), 974–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Globetrender. (2022a). MSocial and citizen M build hotels in the metaverse. Available online: https://globetrender.com/2022/05/19/m-social-citizenm-hotels-metaverse/ (accessed on 9 September 2023).

- Globetrender. (2022b). Rendezverse lets hotels build ‘digital twins’ in the metaverse. Available online: https://globetrender.com/2022/06/23/rendezverse-hotels-digital-twins-metaverse/ (accessed on 10 September 2023).

- Go, H., Kang, M., & Suh, S. C. (2020). Machine learning of robots in tourism and hospitality: Interactive technology acceptance model (iTAM)–cutting edge. Tourism Review, 75(4), 625–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godin, K., Stapleton, J., Kirkpatrick, S. I., Hanning, R. M., & Leatherdale, S. T. (2015). Applying systematic review search methods to the grey literature: A case study examining guidelines for school-based breakfast programs in Canada. Systematic Reviews, 4(1), 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godovykh, M., Baker, C., & Fyall, A. (2022). VR in tourism: A new call for virtual tourism experience amid and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Tourism and Hospitality, 3(1), 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green Globe. (2023). Metaverse—A sustainable first for the Dutch hotel industry. Available online: https://www.greenglobe.com/green-globe-case-studies-blog/rendezverse-mvenpick-hotel-amsterdam-city-centre (accessed on 1 October 2023).

- Gul, S., Shah, T. A., Ahmad, S., Gulzar, F., & Shabir, T. (2021). Is grey literature really grey or a hidden glory to showcase the sleeping beauty. Collection and Curation, 40(3), 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A., Dogra, N., & George, B. (2018). What determines tourist adoption of smartphone apps? An analysis based on the UTAUT-2 framework. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology, 9(1), 50–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D., Lu, L., Nunkoo, R., & Deng, D. (2023). Metaverse in services marketing: An overview and future research directions. The Service Industries Journal, 43(15–16), 1140–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D., Malodia, S., & Dhir, A. (2022). The metaverse in the hospitality and tourism industry: An overview of current trends and future research directions. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 31(5), 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guttentag, D. A. (2010). Virtual reality: Applications and implications for tourism. Tourism Management, 31(5), 637–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayhurst, L. (2022). Iconic Amsterdam hotel joins RENDEZVERSE as it prepares for the web3.0 age. Available online: https://www.travolution.com/news/iconic-amsterdam-hotel-joins-rendezverse-as-it-prepares-for-the-web-3.0-age (accessed on 12 August 2023).

- Hollensen, S., Kotler, P., & Opresnik, M. O. (2023). Metaverse—The new marketing universe. Journal of Business Strategy, 44(3), 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hospitality Net. (2006). Aloft hotels to be the first hotel brand to open its doors in virtual reality. Available online: https://www.hospitalitynet.org/news/4028451.html (accessed on 22 September 2023).

- Hospitality Net. (2022). Demystifying the metaverse for independent hotels. Available online: https://www.hospitalitynet.org/news/4111193.html (accessed on 2 October 2023).

- HOTELS. (2022). The next hottest market? The metaverse. Available online: https://hotelsmag.com/news/the-next-hottest-market-the-metaverse/ (accessed on 28 September 2023).

- Huang, Y. C., Chang, L. L., Yu, C. P., & Chen, J. (2019). Examining an extended technology acceptance model with experience construct on hotel consumers’ adoption of mobile applications. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 28(8), 957–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IHG. (2023). InterContinental hotels & resorts expands artist collaboration with Claire Luxton to Asia-Pacific with first-ever NFT display and all-new immersive art installations. Available online: https://www.ihgplc.com/en/news-and-media/news-releases/2023/intercontinental-hotels-and-resorts-expands-artist-collaboration-with-claire-luxton-to-asia-pacific (accessed on 21 September 2023).

- International Airport Review. (2023). Changi airport enters the metaverse with ChangiVerse. Available online: https://www.internationalairportreview.com/news/184521/changi-airport-enters-the-metaverse-with-changiverse (accessed on 12 August 2023).

- Ioannidis, S., & Georgitseas, P. (2023). Blockchain-enabled fundraising models for tourism destinations (pp. 99–102). AIRSI2023 Books of Abstracts. University of Zaragoza. Available online: https://airsi.unizar.es (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- Ioannidis, S., & Kontis, A. P. (2023a). Metaverse for tourists and tourism destinations. Information Technology and Tourism, 25, 483–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannidis, S., & Kontis, A. P. (2023b). The 4 Epochs of the Metaverse. Journal of Metaverse, 3(2), 152–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, S. (2019). Ultimate transformation: How will automation technologies disrupt the travel, tourism and hospitality industries? Zeitschrift Fur Tourismuswissenschaft, 11(1), 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, S., Webster, C., & Berezina, K. (2017). Adoption of robots and service automation by tourism and hospitality companies. Revista Turismo & Desenvolvimento, 27/28, 1501–1517. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2964308 (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- Jung, T., Cho, J., Han, D. I. D., Ahn, S. J. G., Gupta, M., Das, G., Heo, C. Y., Loureiro, S. M. C., Sigala, M., Trunfio, M., Taylor, A., & tom Dieck, M. C. (2023). Metaverse for service industries: Future applications, opportunities, challenges and research directions. Computers in Human Behavior, 151, 108039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamboj, S., & Joshi, R. (2021). Examining the factors influencing smartphone apps use at tourism destinations: A UTAUT model perspective. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 7(1), 135–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagoz Zeren, S. (2023). The tourism sector in metaverse: Virtual hotel and applications. In F. S. Esen, H. Tinmaz, & M. Singh (Eds.), Metaverse. Studies in big data (Vol. 133). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. (2021). Advertising in the metaverse: Research agenda. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 21(3), 141–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kılıçarslan, Ö., Yozukmaz, N., Albayrak, T., & Buhalis, D. (2025). The impacts of Metaverse on tourist behaviour and marketing implications. Current Issues in Tourism, 28(4), 622–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koohang, A., Nord, J. H., Ooi, K. B., Tan, G. W. H., Al-Emran, M., Aw, E. C. X., Baabdullah, A. M., Buhalis, D., Cham, T. H., Dennis, C., Dutot, V., Dwivedi, Y. K., Hughes, L., Mogaji, E., Pandey, N., Phau, I., Raman, R., Sharma, A., Sigala, M., … Wong, L. W. (2023). Shaping the metaverse into reality: A holistic multidisciplinary understanding of opportunities, challenges, and avenues for future investigation. Journal of Computer Information Systems, 63(3), 735–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kortendick, B. (2022). New frontier: Transforming tourism with NFTs. Available online: https://enjin.io/blog/new-frontier-tourism-nfts (accessed on 8 September 2023).

- Kuru, K. (2023). MetaOmniCity: Towards immersive urban metaverse cyberspaces using smart city digital twins. IEEE Access, 11, 43844–43868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledesma-Chaves, P., Gil-Cordero, E., Navarro-García, A., & Maldonado-López, B. (2024). Satisfaction and performance expectations for the adoption of the metaverse in tourism SMEs. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge, 9(3), 100535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L.-H., Braud, T., Zhou, P., Wang, L., Xu, D., Lin, Z., Kumar, A., Bermejo, C., & Hui, P. (2021). All one needs to know about metaverse: A complete survey on technological singularity, virtual ecosystem, and research agenda. Journal of Latex Class Files, 14(8), 1–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liveleven. (2022). Our story. Available online: https://liveleven.com/about (accessed on 2 October 2023).

- Mahood, Q., Van Eerd, D., & Irvin, E. (2014). Searching for grey literature for systematic reviews: Challenges and benefits. Research Synthesis Method, 5(3), 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariano, K. (2022). Vueling becomes the first airline to sell flights in the metaverse. Available online: https://www.traveldailymedia.com/vueling-becomes-the-first-airline-to-sell-flights-in-the-metaverse (accessed on 11 August 2023).

- Marriott News. (2021). Marriott Bonvoy logs into the metaverse with debut of travel-inspired NFTs. Available online: https://news.marriott.com/news/2021/12/04/marriott-bonvoy-logs-into-the-metaverse-with-debut-of-travel-inspired-nfts (accessed on 12 September 2023).

- McShane, G. (2024). What are utility NFTs? Available online: https://www.coindesk.com/learn/what-are-utility-nfts (accessed on 30 August 2023).

- Meta. (2021). Founder’s letter. Available online: https://about.fb.com/news/2021/10/founders-letter (accessed on 9 July 2023).

- Metinburgh. (2023). Metinburgh. Making the metaverse compelling for all. Available online: https://www.metinburgh.com (accessed on 2 October 2023).

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & The PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 62, 1006–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mystakidis, S. (2022). Metaverse. Encyclopedia, 2(1), 486–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagirikandalage, P., Lakhoua, C., BInsardi, A., Tzempelikos, N., & Kerry, C. (2025). Expert perspectives on factors shaping metaverse adoption for cultural heritage experiences in hospitality industry within an emerging economy. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 37(4), 1332–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naqvi, N. (2023). Metaverse for public good: Embracing the societal impact of metaverse economies. The Journal of The British Blockchain Association, 6(1), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narin, N. G. (2021). A content analysis of the metaverse articles. Journal of Metaverse, 1(1), 17–24. Available online: https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/jmv/issue/67581/1051382 (accessed on 9 September 2023). [CrossRef]

- Niio. (2023). Niio in the press. Available online: https://www.niio.com/site/about/press (accessed on 9 September 2023).

- OpenSea. (2023). Original Crypto Hotel enjoy this beautiful view over crypto land. Available online: https://opensea.io/assets/ethereum/0x495f947276749ce646f68ac8c248420045cb7b5e/90044502762831652073618019479226994723852687107003640717366998198976491028481 (accessed on 1 October 2023).

- Pappas, C., & Williams, I. (2011). Grey literature: Its emerging importance. Journal of Hospital Librarianship, 11(3), 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsi, N. (2022). A virtual hotel to open in the metaverse. Available online: https://www.bdcnetwork.com/virtual-hotel-open-metaverse (accessed on 2 August 2023).

- Petkov, M. (2023). Embracing the metaverse in hospitality: Innovations for the future. Available online: https://landvault.io/blog/metaverse-for-hospitality (accessed on 9 September 2023).

- Rendezverse. (2023). Case studies. Available online: https://rendezverse.com/ (accessed on 1 October 2023).

- Riu Hotels. (2022). Riu hotels is now in the metaverse. Available online: https://www.riu.com/blog/en/we-are-happy-and-very-proud-to-announce-that/ (accessed on 4 September 2023).

- Roomza. (2022). Official website. Available online: www.roomza.com (accessed on 22 September 2023).

- Saundalkar, J. (2022). Neon launches digital twin platform. Available online: https://meconstructionnews.com/51085/neom-launches-digital-twin-metaverse-platform (accessed on 2 August 2023).

- Saunders, E. (2022). Next earth partners with lomob and Vueling airlines to expand its metaverse with first-ever transportation layer. Available online: https://airlinergs.com/next-earth-partners-with-iomob-and-vueling-airlines-to-expand-its-metaverse-with-first-ever-transportation-layer (accessed on 9 August 2023).

- Sensation Hotels. (2023). Welcome to the crypto hotel. Available online: https://unycu.com/cryptohotel (accessed on 1 October 2023).

- Seoul. (2023). Official release of metaverse Seoul. Available online: https://english.seoul.go.kr/official-release-of-metaverse-seoul (accessed on 10 September 2023).

- Seyitoğlu, F., & Ivanov, S. (2022). The “new normal” in the (post-) viral tourism: The role of technology. Tourism: An International Interdisciplinary Journal, 70(2), 151–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheber, A., & Speros, W. (2022). The hotel industry enters the metaverse. Available online: https://hospitalitydesign.com/news/development-destinations/hotel-industry-nfts-metaverse/ (accessed on 30 August 2023).

- Smart City Korea. (2023). Incheon City develops city experience content with global metaverse platform. Available online: https://smartcity.go.kr/en/2023/08/31/인천시-글로벌-메타버스-플랫폼과-함께-도시-경험-콘/ (accessed on 19 September 2023).

- SofokleousIn. (2022). Virtual hotel in the metaverse from CitizenM. Available online: https://www.sofokleousin.gr/eikoniko-ksenodoxeio-sto-metaverse-apo-ti-citizenm (accessed on 8 August 2023).

- South of Scotland. (2023). Borders pupils pioneer tourism metaverse at great tapestry of Scotland. Available online: https://www.ssdalliance.com/borders-pupils-pioneer-tourism-metaverse-at-great-tapestry-of-scotland (accessed on 1 October 2023).

- Speak, S. (2022). RendezVerse to partner with Atlantis, the palm to introduce a virtual version of meetings and events. Available online: https://medium.com/rendezverse/rendezverse-to-partner-with-atlantis-the-palm-to-introduce-a-virtual-version-of-meetings-and-6a28f3ef379b (accessed on 1 October 2023).

- Speros, W. (2022). InterContinental launches NFT collection in the Metaverse. Available online: https://hospitalitydesign.com/news/business-people/ihg-claire-luxton-nfts-metaverse (accessed on 12 August 2023).

- Stansfield, C., Dickson, K., & Bangpan, M. (2016). Exploring issues in the conduct of website searching and other online sources for systematic reviews: How can we be systematic? Systematic Reviews, 5(1), 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephen Gates. (2014). Aloft hotels in second life. Available online: https://stephengates.com/portfolio/aloft-hotels-second-life/ (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Suboh, M. (2023). NEOM’s The Line: The world’s first cognitive city. Available online: https://wired.me/technology/neoms-the-line-the-worlds-first-cognitive-city (accessed on 2 September 2023).

- Tamo, O. (2022). Emirates to expand into the metaverse and launch own NFTs. Available online: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-04-14/emirates-to-expand-into-the-metaverse-and-launch-own-nfts#xj4y7vzkg (accessed on 28 October 2023).

- Tan, C. (2022). Singapore students win Accor’s take off! Challenge with metaverse idea. Available online: https://www.webintravel.com/singapore-students-win-accors-take-off-challenge-with-metaverse-idea (accessed on 12 August 2023).

- The India Express. (2022). Now experience Bengaluru airport’s terminal 2 on metaverse. Available online: https://indianexpress.com/article/cities/bangalore/bengaluru-airport-terminal-2-metaverse-8322672 (accessed on 9 September 2023).

- Thomas, O. (2022). RendezVerse launches into the metaverse at m&i Europe. Available online: https://www.c-mw.net/rendezverse-launches-into-the-metaverse-at-mi-europe (accessed on 9 September 2023).

- Tobies, K., & Maisch, B. (2012). The 3-D innovation sphere: Exploring the use of second life for innovation communication. In N. Zagalo, L. Morgado, & C. Boa-Venture (Eds.), Virtual worlds and metaverse platforms: New communication and identity paradigms (pp. 70–87). IGI Global. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolba, K. (2022). Emirates steps into the digital realm with NFTs and Metaverse experiences. Available online: https://www.aviationbusinessme.com/airlines/emirates-nft-metaverse (accessed on 8 May 2023).

- Töre, V. Ö. (2022). Hilton announces new digital art and NFT pilot program. Available online: https://ftnnews.com/accommodation/44265-hilton-announces-new-digital-art-and-nft-pilot-program (accessed on 5 September 2023).

- TravelFeed. (2023). How metaverse technology is revolutionizing the travel industry. Available online: https://travelfeed.com/@wilsonmarry/how-metaverse-technology-is-revolutionizing-the-travel-industry (accessed on 15 September 2023).

- Trunfio, M., & Pasquinelli, C. (2021). Smart technologies in the Covid-19 crisis: Managing tourism flows and shaping visitors’ behaviour. European Journal of Tourism Research, 29, 2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TTG Asia. (2022). Millennium opens M social decentraland in metaverse. Available online: https://www.ttgasia.com/2022/04/28/millennium-opens-m-social-decentraland-in-metaverse/ (accessed on 6 October 2023).

- TUI Group. (2022). Press release. Available online: https://www.tuigroup.com/en-en/media/press-releases/2022/2022-06-22-riu-plaza-espana-opens-in-metaverse (accessed on 9 September 2023).

- Tussyadiah, I. P., Wang, D., Jung, T. H., & tom Dieck, M. C. (2018). Virtual reality, presence, and attitude change: Empirical evidence from tourism. Tourism Management, 66, 140–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Um, T., Kim, H., Kim, H., Lee, J., Koo, C., & Chung, N. (2022). Travel Incheon as a metaverse: Smart tourism cities development case in Korea. In J. L. Stienmetz, B. Ferrer-Rosell, & D. Massimo (Eds.), Information and communication technologies in tourism 2022. ENTER 2022. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- University of Aberdeen. (2023). Great tapestry of Scotland improving visitor perception. University of Aberdeen. Available online: https://www.abdn.ac.uk/news/16657 (accessed on 4 July 2023).

- Valeri, M., & Baggio, R. (2021). A critical reflection on the adoption of blockchain in tourism. Information Technology & Tourism, 23, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B., & Davis, F. D. (2003). User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Quarterly, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtual Osaka. (2023). Virtual Osaka official webpage. Available online: https://www.virtualosaka.jp/en/#about (accessed on 12 September 2023).

- Volchek, K., & Brysch, A. (2023). Metaverse and Tourism: From a new niche to a transformation. In B. Ferrer-Rosell, D. Massimo, & K. Berezina (Eds.), Information and communication technologies in tourism 2023. ENTER 2023. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VRHTI. (2019). Official webpage. Available online: https://vrhti.com/ (accessed on 10 August 2023).

- Willemse, B. (2023). What is a utility NFT? Available online: https://medium.com/@bram.willemse/what-is-a-utility-nft-355cc426ca01 (accessed on 1 October 2023).

- Wong, L. W., Tan, G. W. H., Ooi, K. B., & Dwivedi, Y. K. (2023). Metaverse in hospitality and tourism: A critical reflection. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 36(7), 2273–2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q., Li, M. Q., & Wang, J. H. (2024). Behavioral Intentions in Metaverse Tourism: An Extended Technology Acceptance Model with Flow Theory. Information, 15(10), 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q., Zhao, Y., Huang, H., Xiong, Z., Kang, J., & Zheng, Z. (2022). Fusing Blockchain and AI With Metaverse: A Survey. IEEE Open Journal of the Computer Society, 3, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, K., Welden, R., Hewett, K., & Haenlein, M. (2023). The merchants of meta: A research agenda to understand the future of retailing in the Metaverse. Journal of Retailing, 99(2), 173–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, S. C., Piscarac, D., & Kang, S. (2022). Digital outdoor advertising tecoration for the metaverse smart city. International Journal of Advanced Culture Technology, 10(1), 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuche, L., & Lanlan, H. (2023). Shanghai starts metaverse services at 20 urban spots as part of pilot program. Available online: https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202301/1283918.shtml (accessed on 8 September 2023).

- Zhang, J., Quoquab, F., & Mohammad, J. (2025). “Do video game players dream of metaverse traveling?” The role of gamification technology and game immersion experience. Tourism Review. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., Ouyang, S., & Tavitiyaman, P. (2022). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on generation Z employees’ perception and behavioral intention toward advanced information technologies in hotels. Tourism and Hospitality, 3(2), 362–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Date | Metaverse-Based Cases | Adoption Drivers | Anticipated Benefits | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | Aloft Hotel | Brand engagement Collect feedback Encourage co-creation Promotion | Entertainment Feeling of co-creation Share feedback | (Hospitality Net, 2006; Brouchoud, 2010; Tobies & Maisch, 2012; Stephen Gates, 2014) |

| 2021 | Atlantis—The Palm Dubai | Brand engagement Distribution channel Enhance guest experience Enrich provided services Promotion Revenue stream | Enhanced experience Entertainment Escapism Help w/decision-making Personalization Socialization Source of information Workplace Reduce costs | (Rendezverse, 2023; Speak, 2022; Globetrender, 2022b) |

| 2021 | Madrid Marriott Auditorium | Brand engagement Distribution channel Enhance guest experience Enrich provided services Promotion Revenue stream | Enhanced experience Entertainment Escapism Help w/decision-making Personalization Socialization Source of information Workplace Reduce costs | (Rendezverse, 2023; Globetrender, 2022b) |

| 2021 | JW Marriott Marquis Dubai | Brand engagement Distribution channel Enhance guest experience Enrich provided services Promotion Revenue stream | Enhanced experience Entertainment Escapism Help w/decision-making Personalization Socialization Source of information Workplace Reduce costs | (Rendezverse, 2023; Globetrender, 2022b) |

| 2021 | Intercontinental Paris Le Grand | Brand engagement Distribution channel Enhance guest experience Enrich provided services Promotion Revenue stream | Enhanced experience Entertainment Escapism Help w/decision-making Personalization Socialization Source of information Workplace Reduce costs | (Rendezverse, 2023; Speak, 2022; Globetrender, 2022b) |

| 2022 | Anantara Grand Hotel Krasnapolsky Amsterdam | Brand engagement Distribution channel Enhance guest experience Enrich provided services Promotion Reduce environ. impact Revenue stream | Enhanced experience Entertainment Escapism Help w/decision-making Personalization Socialization Source of information Workplace Reduce costs | (Escobar, 2022a; Hayhurst, 2022) |

| 2022 | Four Seasons Resort—Bali | Brand engagement Distribution channel Enhance guest experience Enrich provided services Promotion Reduce environ. impact Revenue stream | Enhanced experience Entertainment Escapism Help w/decision-making Personalization Socialization Source of information Workplace Reduce costs | (Petkov, 2023) |

| 2022 | Mövenpick Hotel Amsterdam City Center | Reduce environ. impact Replace website | Enhanced experience Help w/decision-making Personalization Reduce costs Source of information | (Green Globe, 2023; TravelFeed, 2023) |

| 2022 | MSocial Hotel | Brand engagement Community building Distribution channel Promotion | Entertainment Escapism Real-world privileges Socialization | (TTG Asia, 2022; Branding in Asia, 2022; Globetrender, 2022a) |

| 2022 | Riu Plaza España | Brand engagement Distribution channel Enhance guest experience Enrich provided services Promotion Replace website | Enhanced experience Entertainment Help w/decision-making Source of information | (Riu Hotels, 2022; TUI Group, 2022) |

| 2022 | EV Hotel | Community building Enrich provided services Positioning Promotion Revenue stream Rewards program | Enhanced experience Entertainment Escapism Help w/decision-making Personalization Socialization Source of information Workplace Reduce costs | (Buhalis et al., 2023; Escobar, 2022b; EV Hotel Corp., 2022) |

| 2022 | Incheon City | Community building Distribution channel Enhance guest experience Improve residents’ life Promotion Smart city approach | Enhanced experience Entertainment Help w/decision-making Socialization Source of information | (Kuru, 2023; Smart City Korea, 2023; Um et al., 2022; S. C. Yoo et al., 2022) |

| 2022 | Levenverse | Brand engagement Community building Distribution channel Enhance guest experience Enrich provided services Positioning Promotion Revenue stream | Entertainment Escapism Profit generation Socialization Workplace | (Liveleven, 2022) |

| 2022 | CitizenM Hotel | Collect feedback Crowdfunding Encourage co-creation Rewards program | Entertainment Feeling of co-creation Profit generation Real-world privileges Socialization | (Buhalis et al., 2023; Sheber & Speros, 2022; Parsi, 2022; SofokleousIn, 2022) |

| 2022 | Accor Hotels | Brand engagement Community building Distribution channel Empower workforce Enhance guest experience Enrich provided services Promotion Recruitment channel Training tool | Enhanced experience Entertainment Motivational environment Real-world privileges Socialization Source of information Workplace | (Embling, 2023; Bettati, 2023; Accor, 2022; Tan, 2022) |

| 2022 | Roomza Hotels | Empower workforce Enhance guest experience Enrich provided services Reduce costs Reduce environ. impact | Enhanced experience Motivational environment Personalization Privacy Reduce costs Source of information Workplace | (Campbell, 2022; Roomza, 2022; HOTELS, 2022) |

| 2023 | Metaverse Seoul | Community building Distribution channel Enhance guest experience Improve residents’ life Promotion Revenue stream Smart city approach | Enhanced experience entertainment Help w/decision-making Socialization Source of information | (Naqvi, 2023; Seoul, 2023; TravelFeed, 2023) |

| 2023 | NEOM’s The Line | Enhance guest experience Improve residents’ life Promotion Smart city approach | Enhanced experience Entertainment Help w/decision-making Socialization Source of information | (Naqvi, 2023; Suboh, 2023; Saundalkar, 2022) |

| 2023 | Shanghai Metaverse Pilot | Community building Distribution channel Enhance guest experience Improve residents’ life Promotion Smart city approach | Enhanced Experience Entertainment Help w/decision-making Socialization Source of information | (Naqvi, 2023; Yuche & Lanlan, 2023) |

| 2023 | Virtual Osaka | Community building Distribution channel Enhance guest experience Improve residents’ life Promotion Smart city approach | Enhanced experience Entertainment Help w/decision-making Socialization Source of information | (Virtual Osaka, 2023; Wong et al., 2023) |

| 2023 | Metinburgh | Community building Distribution channel Educational tool Enhance guest experience Improve residents’ life Promotion Revenue stream Smart city approach | Enhanced experience Entertainment Help w/decision-making Socialization Source of information Workplace | (Metinburgh, 2023) |

| Date | NFT-Based Cases | Adoption Drivers | Anticipated Benefits | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | Global Power of Travel | Brand engagement Community building Promotion Revenue stream Rewards program | Entertainment Feeling of co-creation Profit generation Real-world privileges | (Marriott News, 2021; Barr, 2021; Karagoz Zeren, 2023) |

| 2022 | NY Hilton Midtown Conrad NY Midtown | Brand engagement Community building Promotion Revenue stream Rewards program | Feeling of co-creation Entertainment Profit generation Real-world privileges | (Hospitality Net, 2022; Töre, 2022; Niio, 2023) |

| 2022 | InterContinental Hotels & Resorts | Brand engagement Community building Positioning Promotion Revenue stream Rewards program | Entertainment Profit generation Real-world privileges | (IHG, 2023; Petkov, 2023; Speros, 2022) |

| 2022 | Great Tapestry of Scotland | Brand engagement Community building Crowdfunding Distribution channel Educational tool Enhance students’ experience Promotion Revenue Stream | Education–training Enhanced experience Entertainment Reduce costs Socialization | (TravelFeed, 2023; Kortendick, 2022; South of Scotland, 2023) |

| 2023 | Crypto Hotels | Brand engagement Community building Revenue stream | Entertainment Escapism Profit generation Socialization | (Sensation Hotels, 2023) |

| Date | Tourism- Complementary Cases | Adoption Drivers | Anticipated Benefits | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | V.R.H.T.I. | Educational tool Enhance students’ experience | Enhanced experience Education–training | (VRHTI, 2019) |

| 2021 | RendezVerse | Enrich offered services Positioning Revenue stream | Metaverse infrastructure | (Rendezverse, 2023; Thomas, 2022) |

| 2022 | AIRSI— The Metaverse Conference | Being relevant Enhance participants’ experience | Enhanced experience Reduce costs Workplace | (Ioannidis & Kontis, 2023b; AIRSI, 2022) |

| 2022 | Emirates Airlines | Brand engagement Community building Educational tool Empower workforce Promotion Reduce costs Revenue stream Rewards program | Enhanced experience Entertainment Education–training Feeling of co-creation Profit generation Reduce costs Real-world privileges Socialization Workplace | (Emirates, 2022, 2023; Accenture, 2022; Tamo, 2022; Tolba, 2022) |

| 2022 | Vueling Airlines | Enhance guest experience Distribution channel Promotion Reduce environ. impact Revenue stream | Enhanced experience Entertainment Profit generation Real-world privileges | (Ahlgren, 2022; Mariano, 2022; Saunders, 2022) |

| 2022 | ChangiVerse | Brand engagement Community building Promotion Revenue stream Rewards program | Entertainment Escapism Profit generation Real-world privileges Socialization | (International Airport Review, 2023; CHANGI, 2023) |

| 2022 | Bangalore International Airport | Community building Enhance guest experience Promotion | Enhanced experience Entertainment | (Naqvi, 2023; Anand, 2022; The India Express, 2022) |

| Real-World Cases | Use of Metaverse | Use of NFTs | Combined Use | TOTAL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hotels | 10 | 4 | 5 | 19 |

| Destinations | 3 | - | 3 | 6 |

| Airline companies | - | - | 2 | 2 |

| Airports | 1 | - | 1 | 2 |

| Tourism conferences | 1 | - | - | 1 |

| IT companies | 1 | - | - | 1 |

| Staff training schools | 1 | - | - | 1 |

| Culture and tourism organizations | - | 1 | - | 1 |

| TOTAL Cases | 17 | 5 | 11 | 33 |

| Adoption Drivers | Metaverse-Based Cases (n) | NFT-Based Cases (n) | Tourism- Complementary Cases (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Promotion | 18 | 4 | 4 |

| Enhance Guest Experience | 17 | 1 | 4 |

| Brand Engagement | 10 | 5 | 2 |

| Distribution Channel | 13 | 1 | 1 |

| Enrich Services | 12 | - | 1 |

| Revenue Stream | 10 | 5 | 4 |

| Community Building | 9 | 5 | 3 |

| Improve Residents’ Life | 6 | - | - |

| Smart City project | 6 | - | - |

| Reduce Environ. Impact | 3 | - | 1 |

| Collect Feedback | 2 | - | - |

| Encourage Co-creation | 2 | - | - |

| Being Relevant | - | - | 1 |

| Positioning | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Educational Tool | - | 1 | 2 |

| Replace Website | 2 | - | - |

| Rewards Program | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Empower Workforce | 1 | - | 1 |

| Crowdfunding channel | 1 | 1 | - |

| Reduce Costs | 1 | - | 1 |

| Enhance Students’ Experience | - | 1 | - |

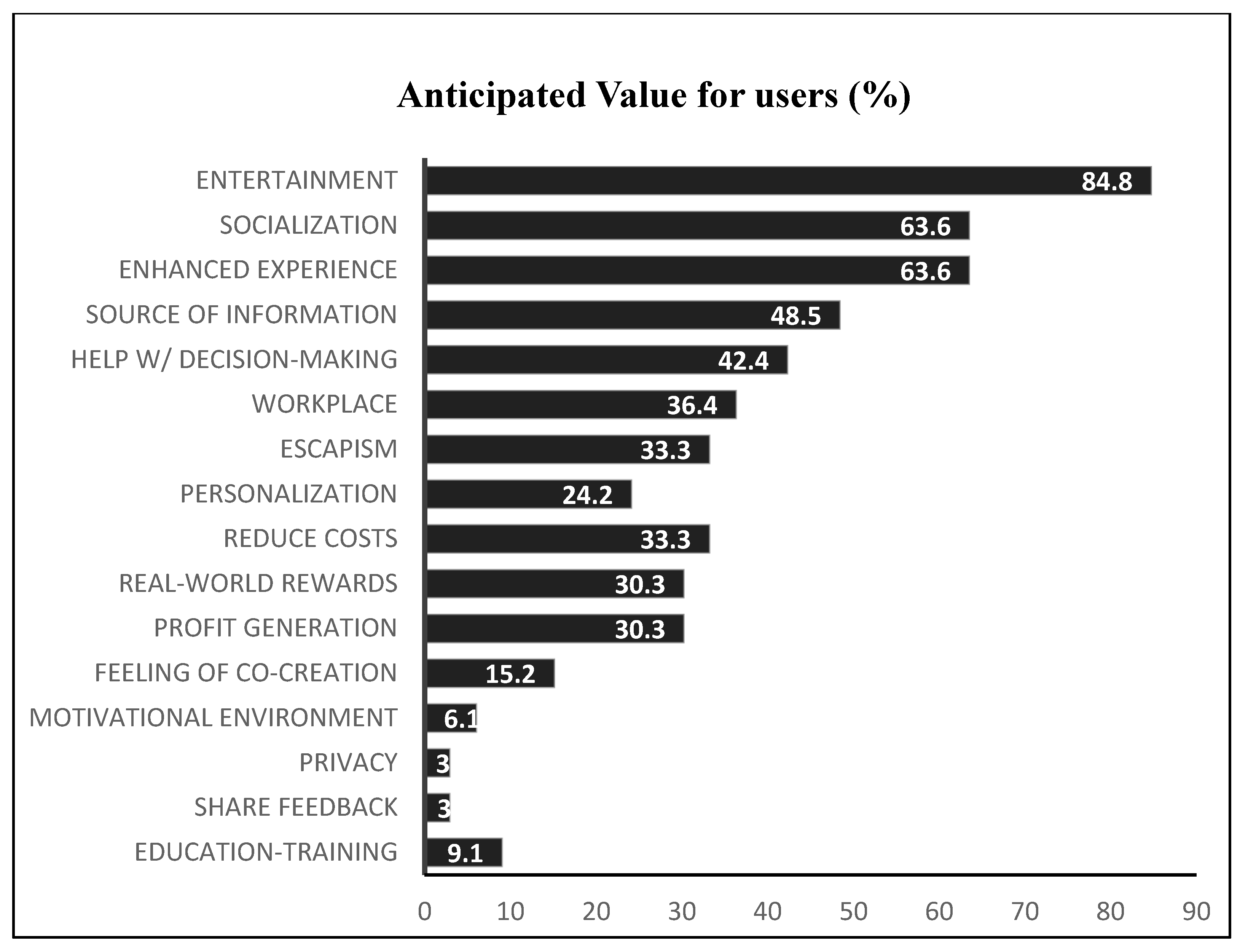

| Anticipated Value | Metaverse-Based (n) | NFTs-Based (n) | Tourism- Complementary (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Entertainment | 19 | 5 | 4 |

| Socialization | 17 | 2 | 2 |

| Enhanced experience * | 16 | 1 | 5 |

| Source of information | 16 | - | - |

| Help with decision-making | 14 | - | - |

| Workplace | 10 | - | 2 |

| Escapism | 9 | 1 | 1 |

| Personalization | 8 | - | - |

| Reduce costs | 8 | 1 | 2 |

| Real-world rewards/privileges | 4 | 3 | 3 |

| Profit generation | 3 | 4 | 3 |

| Feeling of co-creation | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Motivational environment | 2 | - | - |

| Privacy | 1 | - | - |

| Share feedback | 1 | - | - |

| Education–training | - | 1 | 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kontis, A.-P.; Ioannidis, S.A.K. Metaverse Tourism: An Overview of Early Adopters’ Drivers and Anticipated Value for End-Users. Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6020086

Kontis A-P, Ioannidis SAK. Metaverse Tourism: An Overview of Early Adopters’ Drivers and Anticipated Value for End-Users. Tourism and Hospitality. 2025; 6(2):86. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6020086

Chicago/Turabian StyleKontis, Alexios-Patapios, and Stelios A. K. Ioannidis. 2025. "Metaverse Tourism: An Overview of Early Adopters’ Drivers and Anticipated Value for End-Users" Tourism and Hospitality 6, no. 2: 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6020086

APA StyleKontis, A.-P., & Ioannidis, S. A. K. (2025). Metaverse Tourism: An Overview of Early Adopters’ Drivers and Anticipated Value for End-Users. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(2), 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6020086