Optimizing Pollution Control in the Hospitality Sector: A Theoretical Framework for Sustainable Hotel Operations

Abstract

1. Introduction

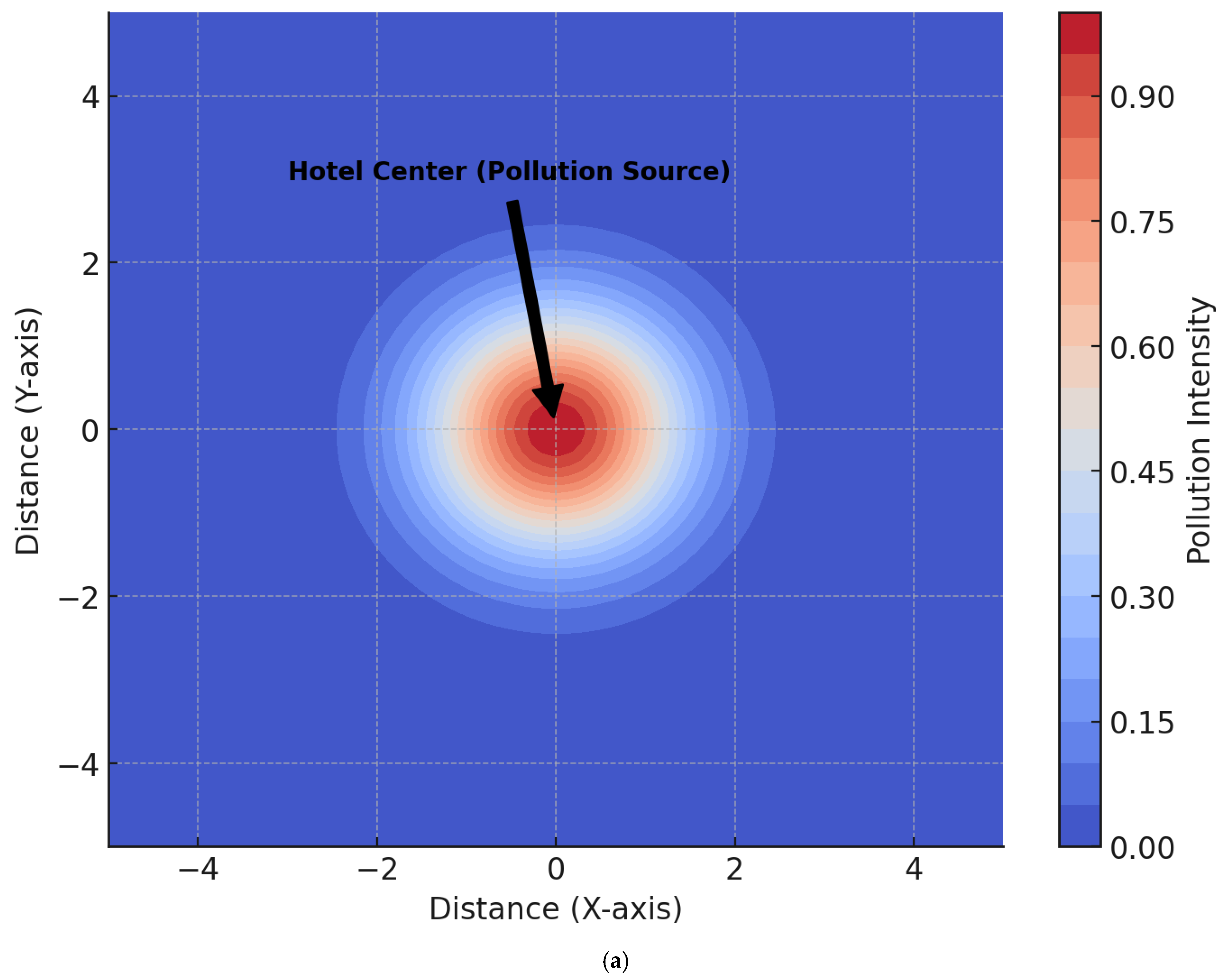

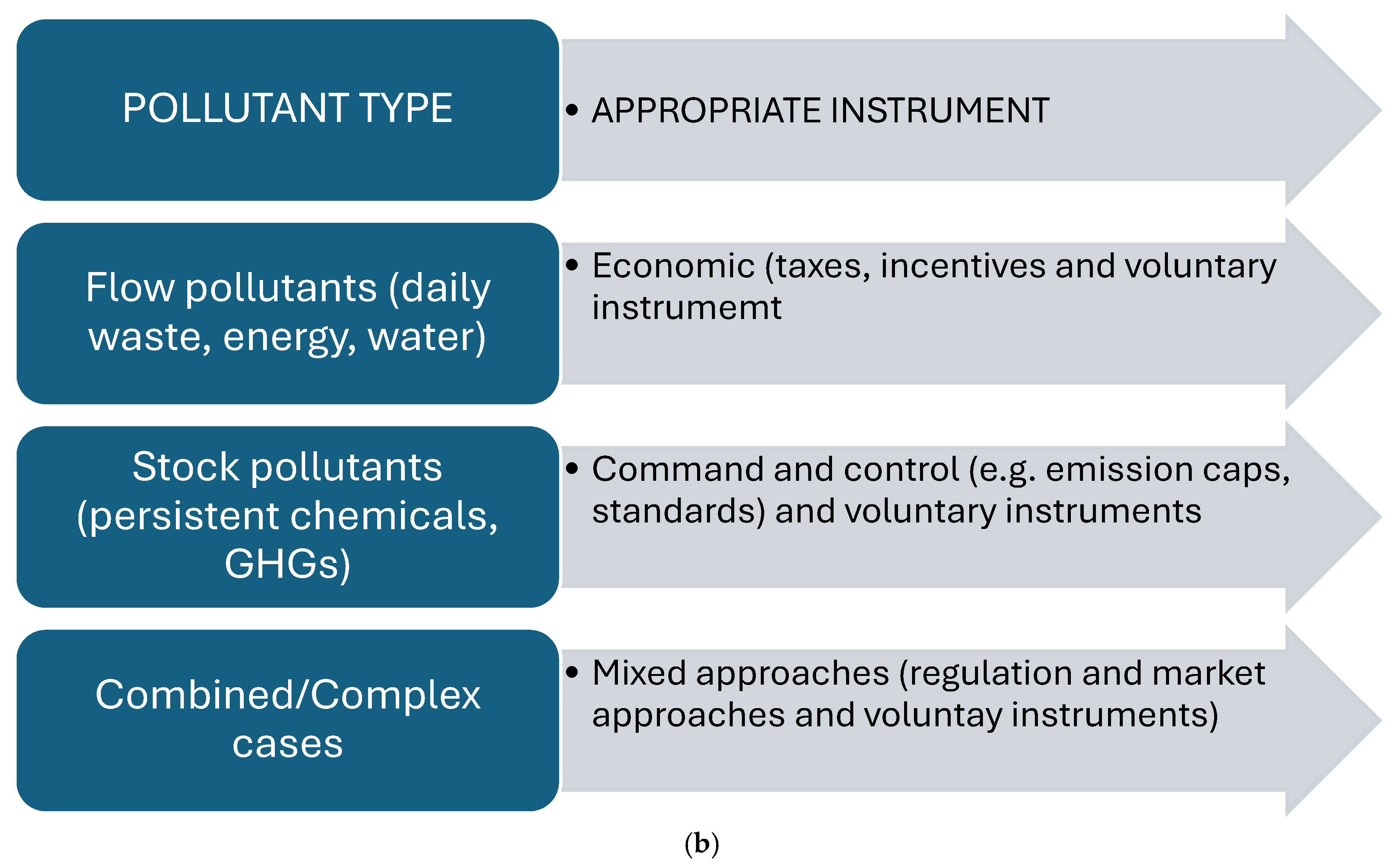

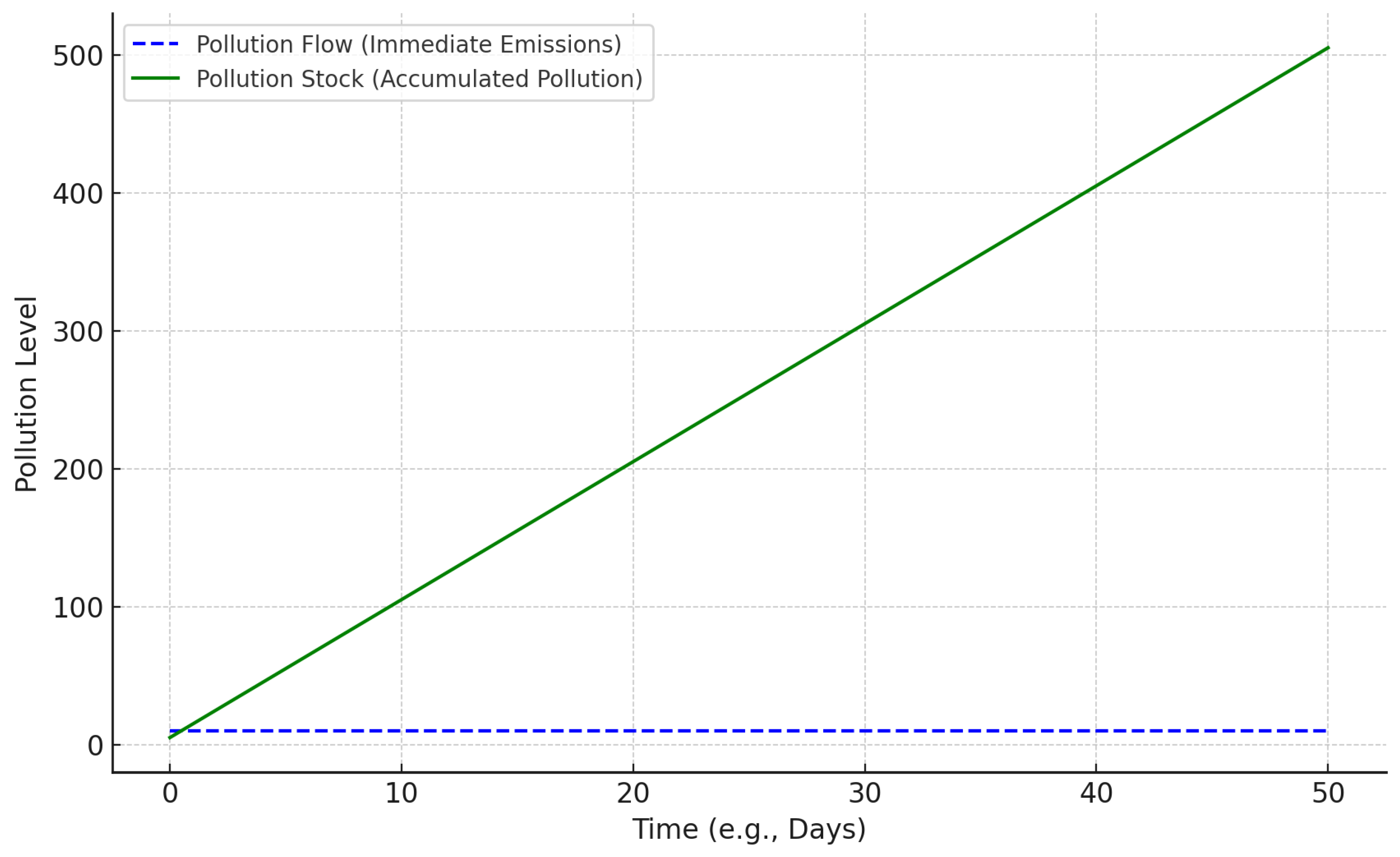

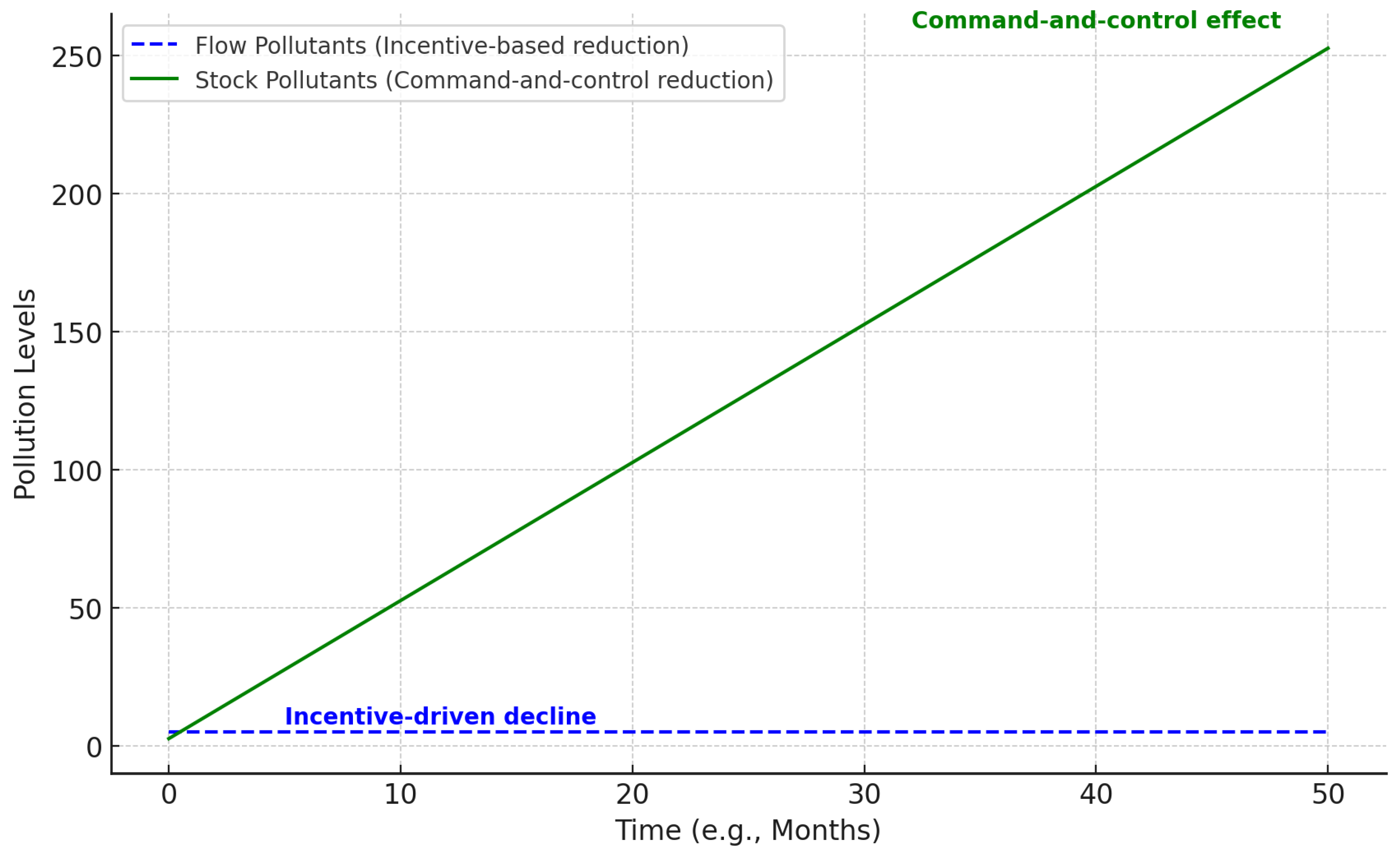

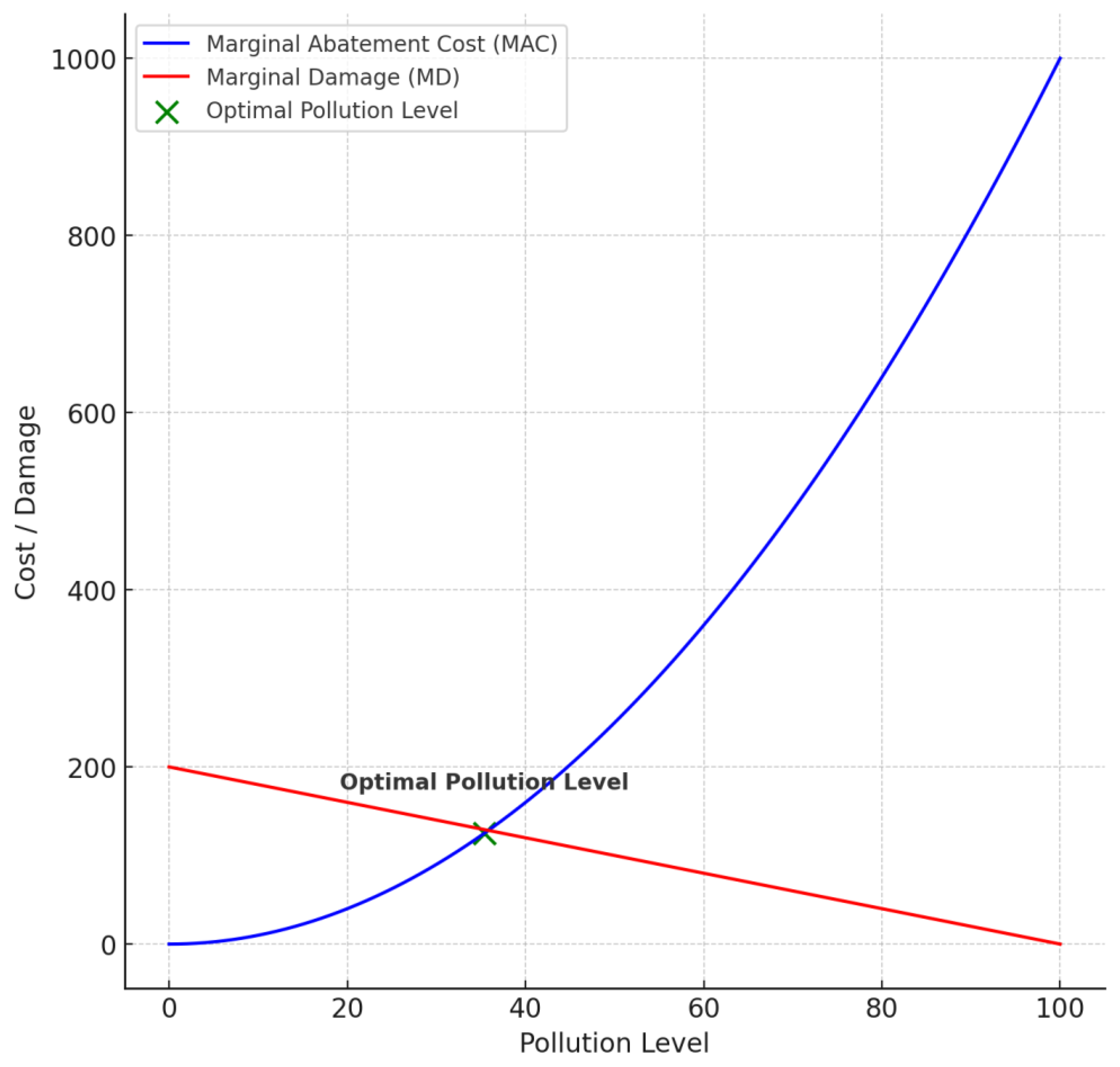

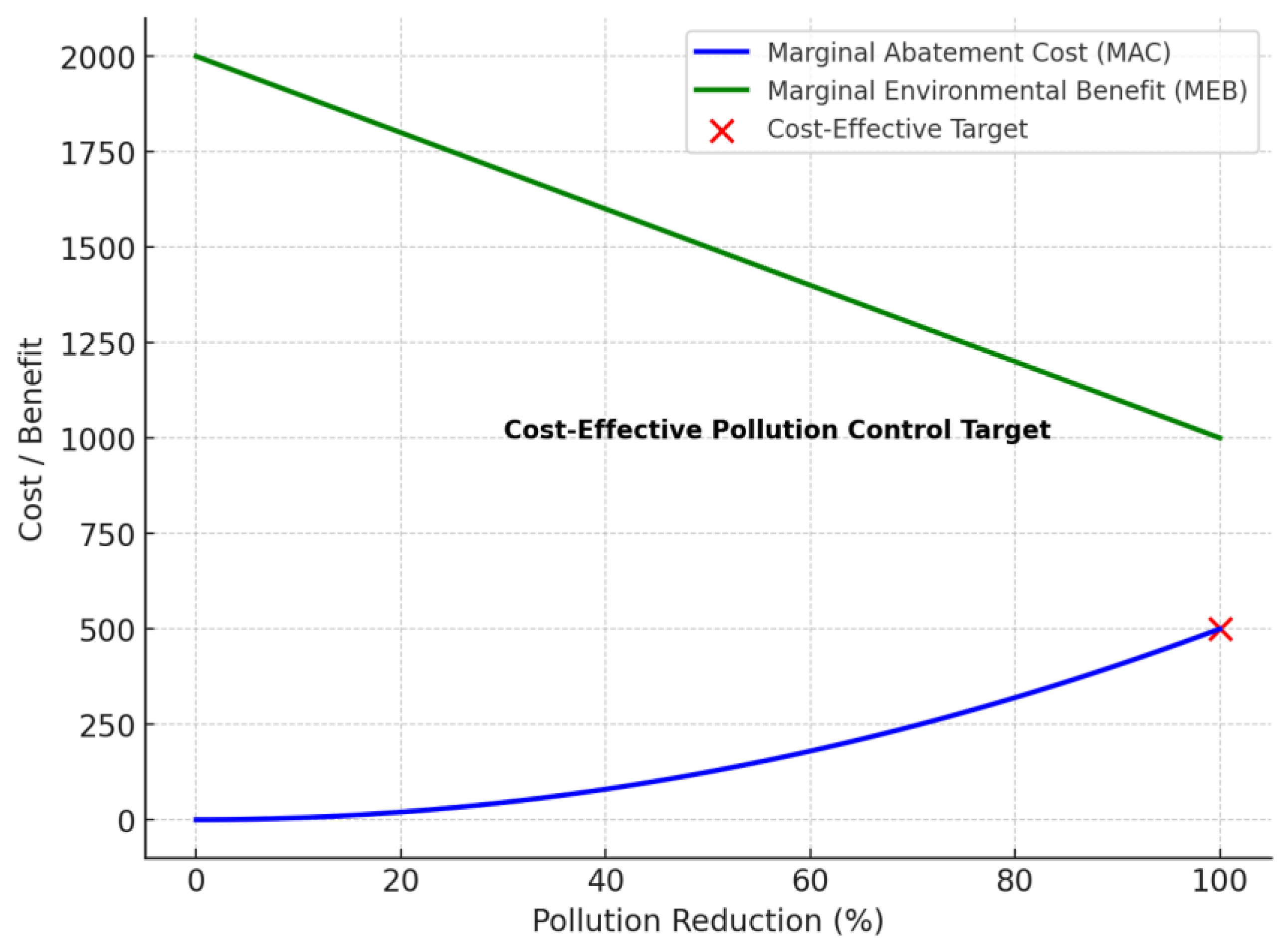

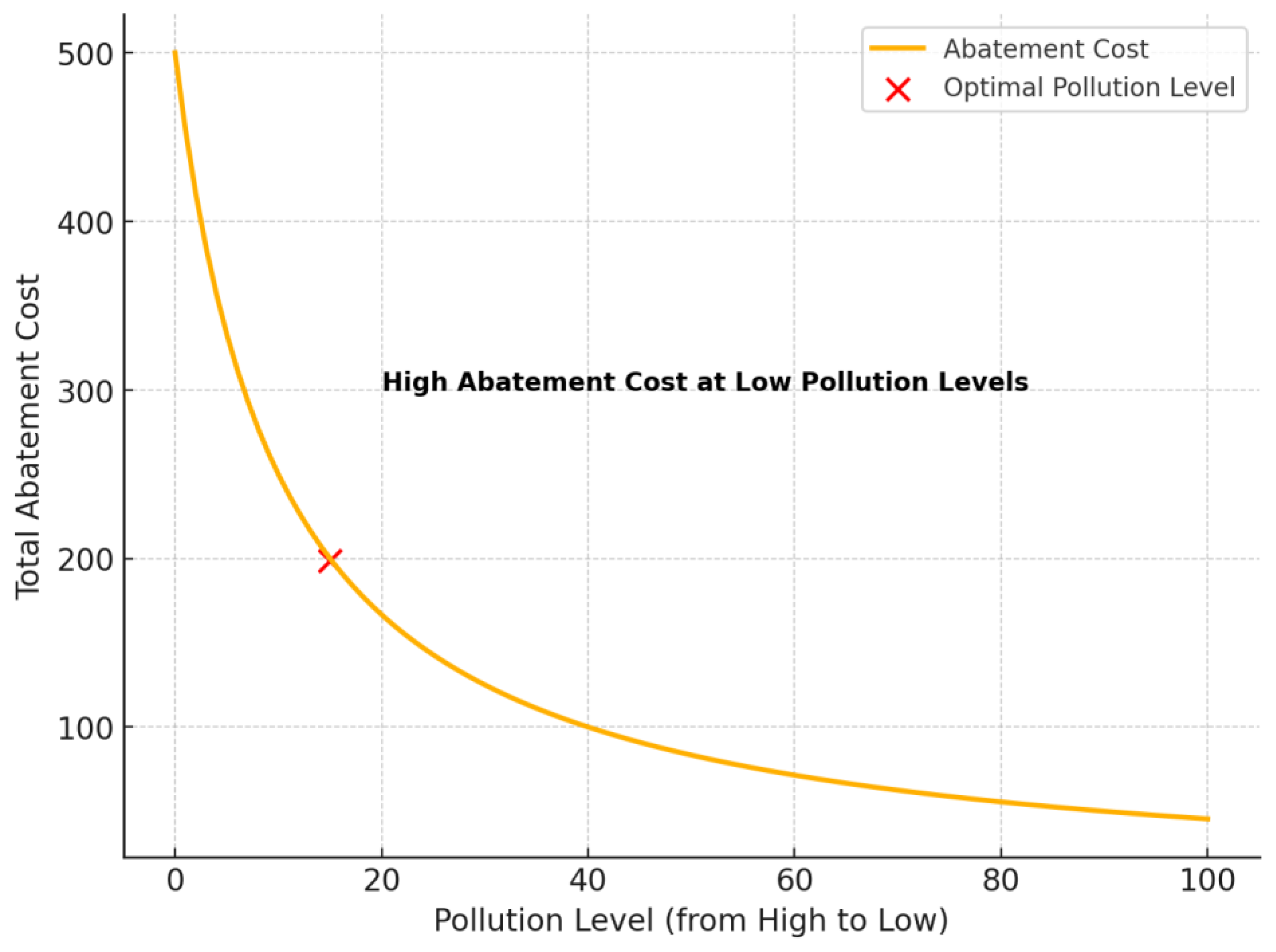

2. Theoretical Framework of Pollution in Hotels

The Conceptual Framework Linking Pollutant Types to Policy Instruments

3. Dynamic Modeling of Pollution in the Hospitality Sector

4. Policy Instruments and Practical Applications for Hotel Sustainability

5. Practical Methods for Pollution Control in Hotels

Types of Pollution Control Instruments

6. Conclusions

6.1. Limitations and Scope of Application

6.2. Future Research Directions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Acampora, A., Preziosi, M., Lucchetti, M. C., & Merli, R. (2022). The Role of hotel environmental communication and guests’ environmental concern in determining guests’ behavioral intentions. Sustainability, 14, 11638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeel, H. B., Sabir, R. I., Shahnawaz, M., & Zafran, M. (2024). Adoption of environmental technologies in the hotel industry: Development of sustainable intelligence and pro-environmental behavior. Discover Sustainability, 5, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASHRAE. (2024). How building decarbonization can transform HVAC. Available online: https://www.ashrae.org/technical-resources/ashrae-journal/featured-articles/how-building-decarbonization-can-transform-hvac (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Babajee, R. B., Seetanah, B., Nunkoo, R., & Gopy-Ramdhany, N. (2021). Corporate social responsibility and hotel financial performance. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 31(2), 226–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengtsson, M., Hotta, Y., Hayashi, S., & Akenji, L. (2010). The four main types of policy instruments. In Policy tools for sustainable materials management: Applications in Asia (pp. 7–15). Institute for Global Environmental Strategies. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep00758.4 (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Ben Youssef, A., & Zeqiri, A. (2022). Hospitality industry 4.0 and climate change. Circular Economy and Sustainability, 2, 1043–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- California Air Resources Board. (2025). Cap-and-trade program. Available online: https://ww2.arb.ca.gov/our-work/programs/cap-and-trade-program (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Cardillo, E., & Longo, M. C. (2024). Exploring the sustainability model of the hospitality firm: The Experience of a hotel group in Europe. In M. H. Bilgin, H. Danis, E. Demir, & M. Zipperling (Eds.), Eurasian business and economics perspectives (BHAAAS EBES 2023 2022. Eurasian Studies in Business and Economics, Vol. 28). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center for Climate and Energy Solutions (C2ES). (2020). Market mechanisms: Understanding the options for climate policy. Available online: https://www.c2es.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/market-mechanisms-options-climate-policy.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (DEFRA). (2019). Clean air strategy 2019. DEFRA. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/clean-air-strategy-2019 (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- EHL Hospitality Insights. (2021). Key statistics on sustainable travel. Available online: https://hospitalityinsights.ehl.edu/sustinable-travel-statistics (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- European Commission. (2025). EU emissions trading system. Available online: https://climate.ec.europa.eu/eu-action/eu-emissions-trading-system-eu-ets_en (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- European Parliament and Council of the European Union. (2000). Directive 2000/60/EC establishing a framework for Community action in the field of water policy. Official Journal of the European Communities, 327, 1–73. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament and Council of the European Union. (2010). Directive 2010/31/EU on the energy performance of buildings. Official Journal of the European Union, 153, 13–35. [Google Scholar]

- Foundation for Environmental Education. (2023). Green key: The international ecolabel for tourism. Available online: https://www.greenkey.global (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Global Sustainable Tourism Council. (2025). About GSTC. Available online: https://www.gstc.org/ (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Government of India. (2007). Energy conservation building code. Available online: https://upsavesenergy.com/SDAActivitiesECBC.aspx#:~:text=The%20Energy%20Conservation%20Building%20Code,of%20120%20KVA%20and%20above (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Gov UK. (2021). Green homes grant: Make energy improvements to your home. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/apply-for-the-green-homes-grant-scheme? (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Gössling, S., & Peeters, P. (2015). Assessing tourism’s global environmental impact 1900–2050. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 23(5), 639–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graci, S., & Dodds, R. (2008). Why go green? The business case for environmental commitment in the canadian hotel industry. Anatolia, 19(2), 251–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greek Tourism Confederation. (2025). Sustainability and Greek tourism. Available online: https://sete.gr/en/sustainability-and-greek-tourism/ (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Green Climate Fund. (2025). About GCF. Available online: https://www.greenclimate.fund (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Halkos, G. E., & Kitsos, C. P. (2005). Optimal pollution level: A theoretical identification. Applied Economics, 37(13), 1475–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellenic Republic. (1997). Joint ministerial decision 5673/400/1997: Measures and conditions for the treatment of urban wastewater (Government Gazette 192/B/14.03.1997). Hellenic Republic. [Google Scholar]

- Hellenic Republic. (2002). Law 3010/2002: Harmonization of law 1650/1986 with directives 97/11/EC and 96/61/EC, regulation of watercourse matters, and other provisions (Government Gazette 91/A/25.4.2002). Hellenic Republic. [Google Scholar]

- Hellenic Republic. (2007). Presidential decree 51/2007: Establishment of measures and procedures for the integrated management and protection of water sources in compliance with directive 2000/60/EC (Government Gazette 54/A/08.03.2007). Hellenic Republic. [Google Scholar]

- Hellenic Republic. (2010). Law 3855/2010: Measures to improve energy efficiency in end-use, energy services, and other provisions (Government Gazette 95/A/23.6.2010). Hellenic Republic. [Google Scholar]

- Hellenic Republic. (2012). Law 4093/2012: Approval of the medium-term fiscal strategy 2013–2016—Urgent Measures for the implementation of law 4046/2012 and the medium-term fiscal strategy 2013–2016 (Government Gazette 222/A/12.11.2012). Hellenic Republic. [Google Scholar]

- Hellenic Republic. (2013). Law 4122/2013: Energy performance of buildings—Harmonization with directive 2010/31/EU and other provisions (Government Gazette 42/A/19.02.2013). Hellenic Republic. [Google Scholar]

- Hellenic Republic. (2015). Law 4342/2015: Transposition of directive 2012/27/EU on energy efficiency, amending laws 3468/2006 and 3855/2010, and other provisions (Government Gazette 143/A/09.11.2015). Hellenic Republic. [Google Scholar]

- Hellenic Republic. (2016). Law 4399/2016: Institutional framework for the establishment of private investment aid schemes for the regional and economic development of the country—Establishment of the development council and other provisions (Government Gazette 117/A/22.06.2016). Hellenic Republic. [Google Scholar]

- Hellenic Republic. (2020). EMAS in Greece. Ministry of Environment and Energy. [Google Scholar]

- Hellenic Republic. (2024). Ministerial decision for the “save energy 2025” program (Government Gazette B’ 6970/2024). Hellenic Republic. [Google Scholar]

- Hellenic Society for the Protection of Nature. (2025). Green key. Available online: https://eepf.gr/en/green-key-3/ (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Hilton. (2024). Our progress. Hilton ESG. Available online: https://esg.hilton.com/our-progress/ (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Hospitality Net. (2014). Hotel sustainability: A full guide for hotel owners. Available online: https://www.hospitalitynet.org/explainer/4120392.html (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Hotel Jakarta Amsterdam. (2024). Sustainability. Available online: https://hoteljakarta.com/sustainability/ (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Idral. (2022). Hotel water consumption. Available online: https://www.idral.it/en/hotel-water-consumption/ (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Jones, P., Hillier, D., & Comfort, D. (2014). Sustainability in the global hotel industry. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 26(1), 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsson, S., Ydstedt, A., & Asen, E. (2020). Looking back on 30 years of carbon taxes in Sweden. Available online: https://taxfoundation.org/research/all/eu/sweden-carbon-tax-revenue-greenhouse-gas-emissions/ (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Kasavan, S., Siron, R., Yusoff, S., & Fakri, M. F. R. (2022). Drivers of food waste generation and best practice towards sustainable food waste management in the hotel sector: A systematic review. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 29, 48152–48167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- KfW. (2023). Energy-efficient construction and refurbishment—For commercial enterprises. Available online: https://www.kfw.de/inlandsfoerderung/Companies/Energy-and-the-environment/ (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Khatter, A. (2023). Challenges and Solutions for Environmental Sustainability in the Hospitality Sector. Sustainability, 15, 11491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatter, A., McGrath, M., Pyke, J., White, L., & Lockstone-Binney, L. (2019). Analysis of hotels’ environmentally sustainable policies and practices: Sustainability and corporate social responsibility in hospitality and tourism. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 31(6), 2394–2410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D. R. (1999). Lowering the cost of pollution control versus controlling pollution. Public Choice, 100, 123–134. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/30026083 (accessed on 9 November 2024). [CrossRef]

- Licera, R. (2025). Hotel/Resort community social responsibility. Available online: https://rubenlicera.com/25373/hotel-resort-community-social-responsibility (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Llausàs, A. (2020). Water use in the tourism accommodation sector. In W. Leal Filho, A. M. Azul, L. Brandli, A. Lange Salvia, & T. Wall (Eds.), Clean water and sanitation (Encyclopedia of the UN sustainable development goals). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Bernabé, E., Foudi, S., Linares, P., & Galarraga, I. (2021). Factors affecting energy-efficiency investment in the hotel industry: Survey results from Spain. Energy Efficiency, 14, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LSE Grantham Research Institute. (2022). Why does climate change get described as a stock-flow problem? LSE Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment. Available online: https://www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/explainers/why-does-climate-change-get-described-as-a-stock-flow-problem/ (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Marriott International. (2024). Sustain: Marriott’s serve 360 platform. Serve 360. Available online: https://serve360.marriott.com/sustain/ (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Menegaki, A. N. (2018). Economic aspects of cyclical implementation in Greek sustainable hospitality. International Journal of Tourism Policy, 8(4), 271–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menegaki, A. N. (2025a). How do tourism and environmental theories intersect? Tourism and Hospitality, 6(1), 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menegaki, A. N. (2025b). Powering down hospitality through a policy-driven, case-based and scenario approach. Energies, 18(2), 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menegaki, A. N., & Agiomirgianakis, G. (2018). Sustainable technologies in Greek tourist accommodation: A quantitative review. European Research Studies, 21(4), 222–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Menegaki, A. N., & Agiomirgianakis, G. (2019). Sustainable technologies in tourist accommodation: A qualitative review. Progress in Industrial Ecology, an International Journal, 13(4), 373–400. [Google Scholar]

- Obahiagbon, E. G., & Kosoe, E. A. (2024). Economic dimensions of air pollution: Cost analysis, valuation, and policy impacts. In The handbook of environmental chemistry. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olorunsola, V. O., Saydam, M. B., Arasli, H., & Sulu, D. (2024). Guest service experience in eco-centric hotels: A content analysis. International Hospitality Review, 38(1), 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Open Access Government. (2018). How can the hospitality industry reduce waste? Available online: https://www.openaccessgovernment.org/hospitality-industry-waste/51174/ (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (1972). Recommendation of the council on guiding principles concerning international economic aspects of environmental policies. OECD Legal Instruments. [Google Scholar]

- Piracha, A., & Chaudhary, M. T. (2022). Urban air pollution, urban heat island and human health: A review of the literature. Sustainability, 14, 9234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remoundou, K., & Koundouri, P. (2009). Environmental effects on public health: An economic perspective. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 6, 2160–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmittmann, J. M. (2023). The financial impact of carbon taxation on corporates (IMF Selected Issues Paper (SIP/2023/034)). International Monetary Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Seguin, C., & Adamowicz, W. (2012). Optimal management of stock pollutants under uncertainty and learning. Presented at SURED 2012: Monte Verità Conference on Sustainable Resource Use and Economic Dynamics, ETH Zurich. Available online: https://ethz.ch/content/dam/ethz/special-interest/mtec/cer-eth/resource-econ-dam/documents/research/sured/sured-2012/SURED-12_083_Seguin.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Shanti, J., & Joshi, G. (2022). Examining the impact of environmentally sustainable practices on hotel brand equity: A case of Bangalore hotels. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 24, 5764–5782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Six Senses Hotels Resorts Spas. (2024). Global tourism plastics initiative. Six Senses Sustainability. Available online: https://www.sixsenses.com/en/sustainability/stories/global-tourism-plastics-initiative (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Skal Europe. (2021). The impact of EU rules for energy efficiency on tourism. Available online: https://www.skaleurope.org/news/the-impact-of-eu-rules-for-energy-efficiency-on-tourism/ (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Smith, S. (2011). The economic theory of efficient pollution control. In Environmental economics: A very short introduction (Very Short Introductions). Oxford Academic. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, M. (2021). How net-zero hotels could make travel more climate-friendly. National Geographic. Available online: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/travel/article/how-net-zero-hotels-could-make-travel-more-climate-friendly (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Sustainable Hospitality Alliance. (2014). Environmental management for hotels. Available online: https://sustainablehospitalityalliance.org/resource/environmental-management-for-hotels/ (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Trevlopoulos, N. S., Tsalis, T. A., Evangelinos, K. I., Vatalis, K. Ι., & Nikolaou, I. E. (2024). The role of environmental regulatory- and proactive-driven corporate strategy in creating corporate green intellectual capital (GIC) and environmental innovation (EI). Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 15, 4750–4775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Global Compact. (2024). One global impact. Available online: https://globalcompactnetwork.org/files/global_compact/United-Nations-Global-Compact-Brochure-2024.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- United Nations. (2013). Volunteers join forces to clean up the mediterranean, united nations environment programme. Available online: https://www.unep.org/unepmap/news/news/volunteers-join-forces-clean-mediterranean (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- United Nations. (2015). Paris agreement, united nations framework convention on climate change (UNFCCC). Available online: https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (2016). Indoor air: The lodging sector. Available online: https://archive.epa.gov/airquality/community/web/html/i-lodging_addl_info.html (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- U.S. Green Building Council. (2025). LEED rating system. Available online: https://www.usgbc.org/leed (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Vatikiotis, A., Kalamara, A., Skourtis, G., Assiouras, I., & Koniordos, M. (2011). Fair trade tourism: The case of South Africa. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/89167282/Fair_Trade_Tourism_The_Case_of_South_Africa (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Velaoras, K., Menegaki, A. N., Polyzos, S., & Gotzamani, K. (2025). The role of environmental certification in the hospitality industry: Assessing sustainability, consumer preferences, and the economic impact. Sustainability, 17(2), 650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voorhees, S. S., Sakai, R., Araki, S., Sato, H., & Otsu, A. (2001). Cost-benefit analysis methods for assessing air pollution control programs in urban environments—A review. Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine 6, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walfisz, J. (2022). A sustainable tourism lab is transforming the island of Rhodes in Greece. Available online: https://www.euronews.com/travel/2022/01/24/a-sustainable-tourism-lab-is-transforming-the-island-of-rhodes-in-greece (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Water NSW. (2024). Legislation and guides. Available online: https://www.waternsw.com.au/about-us/water-in-nsw/legislation-and-guides? (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- World Health Organization. (n.d.). WHO global air quality guidelines. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/who-global-air-quality-guidelines (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Zanni, S., Mura, M., Longo, M., Motta, G., & Caiulo, D. (2023). Indoor air quality monitoring and management in hospitality: An overarching framework. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 35(2), 397–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W., Ji, C., Liu, Y., Hao, Y., Song, Y., Cao, Y., & Qi, H. (2024). Dynamic interactions of carbon trading, green certificate trading, and electricity markets: Insights from system dynamics modeling. PLoS ONE, 19(6), e0304478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Regulatory (Command-and-Control) Instruments | Economic (Market-Based) Instruments | Voluntary Instruments |

|---|---|---|

| Emission Standards | Pollution Taxes | Sustainability Certifications |

| Governments often impose limits on greenhouse gas emissions or indoor air quality. Hotels may need to meet these through efficient HVAC systems or by adopting low-emission technologies. | Some regions impose taxes on waste, energy usage, or emissions. This incentivizes hotels to reduce waste and energy consumption to save costs. | Programs like LEED, Green Key, and EarthCheck assess hotels on a range of sustainability criteria. These certifications signal environmental commitment, attracting eco-conscious guests. |

| Wastewater Treatment Regulations | Tradable Permits | Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Initiatives |

| Many areas require hotels to treat wastewater before disposal, especially for hotels with on-site facilities like swimming pools and laundries. | In areas with cap-and-trade systems, hotels can purchase emissions permits. If a hotel emits less than its allocated amount, it can sell remaining permits, adding a financial incentive to reduce pollution. | Many hotels adopt internal sustainability goals, such as reducing plastic use or conserving water, and report these in CSR statements to enhance brand reputation. |

| Energy Efficiency Standards | Subsidies and Grants for Green Investments | Public-Private Partnerships (PPP) |

| Standards for energy consumption in buildings, such as the EU’s Energy Performance of Buildings Directive, encourage hotels to adopt energy-efficient lighting, appliances, and systems. | Governments often offer subsidies or grants for renewable energy installations, water recycling systems, or waste management facilities. These help hotels cover the initial costs of implementing sustainable practices. | Some hotels partner with government agencies or NGOs to launch sustainable initiatives, like reforestation programs or eco-friendly community projects, which promote positive environmental impacts and social responsibility. |

| Regulatory (Command-and-Control) Instruments | Economic (Market-Based) Instruments | Voluntary Instruments |

|---|---|---|

| Emission Standards | Pollution Taxes | Sustainability Certifications |

| Emission Standards: The Paris Agreement (United Nations, 2015) encourages countries to set national policies for reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Although not hotel-specific, it impacts hotels as countries translate these targets into domestic regulations. | Pollution Taxes: The OECD Guidelines on Polluter Pays Principle encourage countries to impose pollution-related taxes. While not enforceable, many countries have adopted this principle, applying taxes on emissions and waste. | Sustainability Certifications: LEED Certification (U.S. Green Building Council) is widely recognized globally and used by hotels to demonstrate commitment to environmental standards. |

| Wastewater Treatment Regulations | Tradable Permits | Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Initiatives |

| Wastewater Treatment Regulations: The European Union Water Framework Directive requires all member states to achieve good qualitative and quantitative status of water bodies, including mandates on wastewater discharge. | Tradable Permits: The EU Emissions Trading System (ETS) allows hotels and other industries within the EU to buy and sell emissions permits, setting a cap on total emissions and encouraging reductions where economically feasible. | Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Initiatives: The UN Global Compact encourages businesses, including hotels, to adopt sustainable practices aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). |

| Energy Efficiency Standards | Subsidies and Grants for Green Investments | Public-Private Partnerships (PPP) |

| Energy Efficiency Standards: The EU Energy Performance of Buildings Directive mandates energy efficiency improvements in buildings, covering hotel construction and renovations. | Subsidies and Grants for Green Investments: The UN Green Climate Fund offers financing for developing countries, including projects in the hotel sector for adopting renewable energy. | Public-Private Partnerships (PPP): The Global Sustainable Tourism Council (GSTC) partners with governments and private sectors to encourage sustainable tourism, including programs that hotels can join to promote eco-friendly operations. |

| Regulatory (Command-and-Control) Instruments | Economic (Market-Based) Instruments | Voluntary Instruments |

|---|---|---|

| Emission Standards | Pollution Taxes | Sustainability Certifications |

| Emission Standards: The Clean Air Act in the United States sets air quality standards, including limits on emissions that hotels must follow, particularly regarding heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) systems. | Pollution Taxes: Japan’s Carbon Tax imposes a levy on fossil fuels based on CO2 emissions, affecting energy costs for hotels using conventional energy sources. Similarly, Sweden’s Carbon Tax incentivizes hotels to reduce fossil fuel reliance to minimize costs. | Sustainability Certifications: Green Key Certification (based in Denmark) is an eco-label awarded to hotels and other establishments meeting sustainable practices, commonly used across Europe. |

| Wastewater Treatment Regulations | Tradable Permits | Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Initiatives |

| Wastewater Treatment Regulations: In Australia, the Water Management Act 2000 (New South Wales) requires commercial establishments, including hotels, to treat and dispose of wastewater in compliance with specific standards. | Tradable Permits: California’s Cap-and-Trade Program in the U.S. requires certain industries, including large commercial facilities, to comply with emissions caps, with permits that can be traded or banked. | Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Initiatives: In the Philippines, the Green Hotels Initiative promotes CSR initiatives tailored to hotels, focusing on reducing environmental impacts through community engagement and sustainable practices. |

| Energy Efficiency Standards | Subsidies and Grants for Green Investments | Public-Private Partnerships (PPP) |

| Energy Efficiency Standards: The Energy Conservation Building Code (ECBC) in India sets minimum energy standards for new commercial buildings, including hotels, to promote efficient energy use. | Subsidies and Grants for Green Investments: Germany’s KfW Bank offers low-interest loans for energy-efficient upgrades in buildings, helping hotels implement green technologies. The UK’s Green Homes Grant previously offered financial support for energy-saving improvements, accessible to commercial properties, including hotels. | Public-Private Partnerships (PPP): In South Africa, the Fair Trade Tourism initiative works with hotels to meet social and environmental standards, often in partnership with governmental and non-governmental organizations. |

| Regulatory (Command-and-Control) Instruments | Economic (Market-Based) Instruments | Voluntary Instruments |

|---|---|---|

| Emission Standards | Pollution Taxes | Sustainability Certifications |

| Greek Law 3010/2002 aligns Greece with the EU’s Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) standards, regulating emissions from commercial establishments, including hotels. It requires environmental impact studies and controls to minimize emissions, especially in high-tourism areas. Law 3855/2010 promotes energy efficiency and renewable energy use, mandating that large buildings, such as hotels, meet specific energy efficiency standards, indirectly reducing emissions from heating, cooling, and electricity. | Special Environmental Tax on Energy (Law 4093/2012) introduces an environmental tax on energy consumption, affecting electricity and fossil fuel costs. Hotels are encouraged to reduce energy use or switch to renewable sources to lower costs. | Green Key Eco-Label: Administered in Greece by the Hellenic Society for the Protection of Nature, this certification is awarded to hotels that meet international sustainability standards in waste management, energy, and water conservation. EMAS (Eco-Management and Audit Scheme): Some Greek hotels participate in EMAS, an EU voluntary certification for organizations committed to improving their environmental performance. It’s widely recognized and respected in Greece’s tourism sector. |

| Wastewater Treatment Regulations | Tradable Permits | Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Initiatives |

| Presidential Decree 51/2007 transposes the EU Water Framework Directive into Greek law, requiring all establishments, including hotels, to manage and treat wastewater to protect water quality. Joint Ministerial Decision 5673/400/1997 sets specific standards for the disposal of wastewater from hotels and other facilities, mandating adequate treatment before discharge, especially in coastal and island regions. | Participation in the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS): Greece participates in the EU ETS, which applies to larger establishments, including hotels that consume significant energy. Hotels can buy and sell emissions permits, giving them flexibility in managing their emissions under an overall cap. | Greek Tourism Confederation (SETE) CSR Initiatives: SETE encourages hotels to adopt CSR practices, including energy conservation, waste reduction, and community engagement, particularly in areas with high environmental sensitivity. Hellenic Federation of Hoteliers: Through this body, Greek hotels often participate in voluntary environmental programs, such as supporting local conservation projects or adopting sustainable supply chains. |

| Energy Efficiency Standards | Subsidies and Grants for Green Investments | Public-Private Partnerships (PPP) |

| Law 4342/2015 on Energy Efficiency adopts the EU Energy Efficiency Directive, requiring energy audits and energy efficiency measures for large hotels. Hotels must comply with standards for heating, insulation, lighting, and HVAC systems. Law 4122/2013, which implements the EU Directive on Energy Performance of Buildings, mandates that new or significantly renovated hotels meet minimum energy performance standards. | “Save Energy 2025” Program Funded by the Greek government and the EU, this program offers subsidies for energy-saving renovations in commercial properties, including hotels. Eligible projects include the installation of energy-efficient windows, insulation, and renewable energy systems. Development Law 4399/2016 provides grants and tax incentives for investments in energy efficiency and environmental sustainability. Hotels can receive funding for sustainable upgrades like solar panels, water recycling systems, and energy-efficient appliances. | Sustainable Island Tourism Initiatives: In collaboration with local municipalities and NGOs, the Greek Ministry of Tourism promotes sustainable tourism on popular islands like Crete and Rhodes, where hotels are encouraged to participate in local environmental projects, such as beach clean-ups and marine conservation efforts. Collaborations with the Mediterranean SOS Network: Hotels across Greece, especially those along the coast, partner with this NGO to promote sustainable practices, focusing on waste reduction, water conservation, and environmental awareness programs for tourists. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Menegaki, A.N. Optimizing Pollution Control in the Hospitality Sector: A Theoretical Framework for Sustainable Hotel Operations. Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6020085

Menegaki AN. Optimizing Pollution Control in the Hospitality Sector: A Theoretical Framework for Sustainable Hotel Operations. Tourism and Hospitality. 2025; 6(2):85. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6020085

Chicago/Turabian StyleMenegaki, Angeliki N. 2025. "Optimizing Pollution Control in the Hospitality Sector: A Theoretical Framework for Sustainable Hotel Operations" Tourism and Hospitality 6, no. 2: 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6020085

APA StyleMenegaki, A. N. (2025). Optimizing Pollution Control in the Hospitality Sector: A Theoretical Framework for Sustainable Hotel Operations. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(2), 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6020085