Abstract

This study explores the relationship between perceived quality and happiness among self-driving tourists, focusing on the impact of the self-driving journey and sightseeing stages on multi-stage satisfaction and happiness. An online survey was conducted, and a Structural Equation Model (SEM) of perceived quality, satisfaction, and happiness was constructed to test the hypotheses. The results indicate that overall satisfaction with the self-driving experience significantly affects tourists’ happiness, with the indirect effect of attraction satisfaction being particularly notable. Perceived quality indirectly influences happiness by enhancing satisfaction, with key factors including unique attractions, guide services, and innovative entertainment products. Additionally, the development of self-driving parking facilities, public information dissemination, road key nodes and scenery design, and vehicle intelligence levels are critical to enhancing tourists’ happiness. This study provides a theoretical basis for improving the overall tourism experience.

1. Introduction

In recent years, with the continuous improvement of living standards and the diversification of leisure activities, tourism has become an important means for individuals to pursue emotional satisfaction and enhance overall happiness. Among various forms of tourism, self-driving tourism has grown rapidly due to its flexibility, personalization, and deep experiential characteristics. Understanding how tourism experiences, particularly within the context of self-driving travel, influence individual happiness has thus become an increasingly important area of academic inquiry.

The study of happiness from a psychological perspective began in the 1960s. Wilson’s (1967) summary of the research on happiness marked the transition of happiness research from philosophy to psychology. Subsequently, the rise of positive psychology further shifted happiness research toward a scientific approach. From a social perspective, happiness is closely linked to people’s quality of life. In 1980, the Manila Declaration on World Tourism proclaimed that tourism is a fundamental right of individuals, contributing to improving quality of life and creating better living conditions for all (World Tourism Organization, 1980). The Notice on Issuing the 14th Five-Year Plan for Tourism Development (State Council of the People’s Republic of China, 2021) defines tourism as a significant happiness industry characterized by its contemporary relevance.

Current research on the impact of tourism on happiness primarily focuses on antecedents and behaviors. Research indicates that tourists’ well-being is closely linked to the overall value of their tourism experience (X. Zhang et al., 2020). Enhancing the quality of public tourism services and increasing satisfaction with the experience can significantly improve tourists’ sense of well-being (Shen et al., 2023). Furthermore, well-being during tourism activities is strongly associated with positive emotions and a sense of accomplishment (Gillet et al., 2013). Studies have also demonstrated that participation in leisure activities and satisfaction derived from these activities have a positive impact on subjective well-being (X. R. Wang & Sun, 2019). These findings suggest that individuals seek novel experiences through tourism not only to rejuvenate both body and mind but also to attain happiness (Y. Chen et al., 2020). The interplay of factors such as tourism experience, service quality, satisfaction, and leisure activities collectively shape the overall sense of well-being in tourism.

Existing studies on tourism happiness predominantly measure subjective well-being and psychological well-being within the field of psychology (Qiao, 2022). Subjective well-being encompasses a combination of positive emotions and life satisfaction (Tuo, 2015), emphasizing individuals’ overall evaluations of quality of life. Psychological well-being encompasses deeper experiences such as autonomy, personal growth, and life purpose. From the tourism perspective, Filep (2012) proposed that happiness consists of positive emotions, engagement, and meaning, considering the stage characteristics of the travel experience; Tuo et al. (2020) conducted in-depth interviews using prototype theory, summarizing tourism happiness into six dimensions: positive emotions, a sense of control, personal growth, achievement experiences, social connection, and immersive experiences. In research on the factors influencing happiness, Han (2023) and C. X. Xu and Zheng (2021) found that psychological latent variables are positively associated with happiness. However, most studies employ the concept of happiness in a general sense without linking it to specific scenarios. Therefore, the existing studies integrate the travel process with the attraction tourism process and propose an analysis of satisfaction and happiness from the perspective of whole-process tourism.

With the increasing popularity of automobiles and significant improvements in individuals’ means and ability to access information, self-driving travel has become a widely chosen mode of tourism. Unlike traditional tourism methods, self-driving tourists can arrange travel times and routes more autonomously, deeply experience cultural and natural beauty, and explore the world. The journey itself offers scenic views, leisure opportunities, and consumer experiences. According to the “Deep Analysis of the Development of the Self-Driving Tourism Industry in China (2023–2030)”, self-driving tourism accounted for 64% of domestic tourism in 2019, with a year-on-year growth of 39% in popularity after 2023.

Current research predominantly measures self-driving tourists’ travel experiences through visitor satisfaction (Pizam, 2005), focusing on the perception of quality concerning attraction services and self-driving travel. Jiao and Zhou (2021) constructed an SEM and found that tourists’ perceptions of transportation, information, and guide services positively influenced satisfaction with self-driving tourism at attractions. J. Y. Yang (2022) employed multiple linear regression and found that road traffic conditions and the value of attraction resources significantly affect self-driving satisfaction. Nie (2018) explored the impact of environments, services, social factors, and culture in highway service areas on the self-driving experience. However, few existing studies focus on the whole-process travel experience of self-driving tourism. Gao (2018) only examines the influence of multiple stages on overall satisfaction from a travel perspective. Therefore, this paper investigates the transmission mechanisms and interactions between the transportation and attraction stages in relation to overall process satisfaction, aiming to fill this gap in the literature.

China has made the development of the tourism industry is a crucial focus for promoting high-quality development. The integration of self-driving tourists’ travel and the tourism process creates a combined tourism experience involving both attractions and the journey. Investigating the impact mechanism between perceived quality, overall satisfaction, and happiness for self-driving tourists is significant for enhancing their tourism happiness and promoting the sustainable development of self-driving tourism. Existing literature on perceived quality only considers a single scenario of self-driving trips (C. Zhang, 2018) or attractions (Shi et al., 2014), and it lacks an integrated perspective on what perceived quality affects self-driving tourists in the whole process of traveling. Traditional perceived quality is mostly obtained through literature searches and questionnaire surveys, which have high costs and difficulty with sampling, causing a certain amount of concern about the reliability of the evaluations (Yan et al., 2011). In contrast, the travel review websites data, as a form of unsolicited, spontaneous evaluation, provides a rich and authentic reflection of tourists’ perceptions and priorities (Heipke, 2010). Therefore, analyzing travel review websites data offers a practical approach to capturing tourists’ perception needs across the entire process of self-driving tourism.

Building on these research gaps, this study adopts a needs-based perspective to investigate the experience of self-driving tourists. First, it identifies and extracts tourists’ perceived quality from two stages: self-driving travel and attraction visits. Second, since self-driving tourism consists of a combination of multiple stages of travel and exploration, this paper categorizes satisfaction into three dimensions: self-driving satisfaction, attraction satisfaction, and overall satisfaction throughout the self-driving experience. Lastly, based on the tourism happiness scale (Tuo et al., 2020), this research constructs a SEM framed around “perceived quality—satisfaction—happiness” to explore the factors influencing the travel experiences of self-driving tourists and, subsequently, enhance their happiness at a deeper level. The specific contributions of this paper include: (1) screening overall perceived quality based on existing literature and travel review websites data to capture the latest needs of self-driving tourists; (2) considering the “travel + exploration” characteristics of self-driving tourism, identifying key factors that enhance tourist happiness and examining the relationship between stage satisfaction (attraction satisfaction and self-driving satisfaction) and overall satisfaction, thereby providing new insights for the rational allocation of self-driving tourism resources; (3) utilizing a happiness scale from the tourists’ perspective to better measure the happiness of self-driving tourists. Through these efforts, the study aims to offer both theoretical enrichment and practical strategies for enhancing tourists’ happiness and advancing the sustainable growth of self-driving tourism.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 outlines the research framework and contributions, including tourists’ perceived quality, tourist satisfaction, and model development. Section 3 details the survey design and preliminary analysis, covering questionnaire design and data collection. Section 4 presents the model testing and result analysis, including the evaluation and testing of the measurement model, model parameter estimation results, and an analysis of the impact of self-driving tourists’ perceived quality on their well-being. Section 5 explores the results, with contributions from theory and practice. Finally, Section 6 discusses the conclusions, implications, and future research directions.

2. Research Framework and Contributions

2.1. Tourist Perceived Quality

Tourist perceived quality was initially defined from the customer’s perspective. As the concept developed, scholars have primarily defined it from the comparative perspective of tourists’ expectations and actual perceptions. In this study, tourist perceived quality is defined as the overall attitude or evaluation that tourists provide when comparing their actual perceptions of the service quality in a tourist area to their prior expectations.

In terms of dimensional classification, the GM model differentiates quality from both technical and functional aspects (Grönroos, 1984), while the SERVQUAL model measures service quality differences through responsiveness, reliability, empathy, assurance, and tangibles (Parasuraman et al., 1988; Alsiehemy, 2023). Existing research on attractions often focuses on product quality, such as tourist landscapes, cultural heritage, infrastructure, and entertainment facilities, as well as service quality, including guide explanations and attitudes of service personnel (Baker & Crompton, 2000; Akama & Kieti, 2003). C. Zhang (2018) categorizes perceived quality into cultural, tangible, communicative, and convenient dimensions. When investigating the key factors affecting the customer experience at the night market, service quality was categorized into four dimensions: image, responsibility, reliability, and technical excellence (Suvittawat, 2024). However, research on perceived quality in self-driving tourism is relatively scarce. Shi et al. (2014) considered the freedom of the driving route, travel comfort, and cost perception. Li et al. (2020) included the quality of roadway infrastructure and parking facilities in their assessment.

In this study, we conducted a semantic analysis of self-driving tourists’ travel review website data from two Chinese travel platforms, Dianping and Ctrip, and combined it with the literature on perceived quality of tourism. We classified perceived quality into seven constructs, including road conditions and travel quality of self-driving trips, service facilities at attractions, transportation services, tourism entertainment, and tourism resources.

2.2. Tourist Satisfaction

Pizam (2005) was the first to introduce the concept of customer satisfaction into tourism research. Currently, tourist satisfaction is evaluated by comparing pre-travel expectations with post-travel perceptions regarding a destination. Since tourist satisfaction is a crucial indicator for assessing the quality of tourist destinations (J. Wu et al., 2022), this paper focuses on self-driving tourists and suggests that overall satisfaction with the self-driving experience encompasses both self-driving travel and attraction satisfaction. This is defined as a comprehensive evaluation of the service quality and management level throughout the entire perceived travel process and scenic area tour, comparing pre-tourist expectations with post-tourism experiences.

In terms of attraction satisfaction, different tourism destinations have unique resource characteristics, resulting in varying influencing factors on tourist satisfaction, including the quality of hardware facilities, service quality (Q. F. Ma et al., 2017), and tourist psychology (Q. Zhang, 2020). Research on satisfaction in self-driving tourism is limited, and studies investigating the relationship between multi-stage satisfaction and overall satisfaction are rare. F. Wu (2021) developed a self-driving tourism friendliness system based on route friendliness, information friendliness, regional friendliness, attraction friendliness, and behavioral friendliness. B. Wang et al. (2017) expanded on existing research by incorporating vehicle-related factors and found that elements such as traffic flow, highways, road signs and indicators, and parking spaces significantly influence tourists’ satisfaction and loyalty in the context of car tourism. Tourists can not only experience relaxation away from the hustle and bustle through self-driving activities, but also achieve a sense of self-worth by challenging themselves, thereby obtaining spiritual satisfaction and enjoyment (Li et al., 2020). Kahneman (2000) posited that overall satisfaction ratings often reflect a function of peak travel satisfaction and the satisfaction from the most recent travel experience.

2.3. Model Construction

This study constructs a comprehensive scenario integrating transportation and attraction-based tourism, examining tourist satisfaction and well-being within this context. By analyzing the entire process rather than focusing on a single stage, the study aims to systematically investigate satisfaction from the perspective of tourists engaged in self-driving travel. It explores the transmission mechanisms of satisfaction across different stages, as well as their interactive effects, to understand the contribution of each stage to overall satisfaction. Furthermore, it identifies key qualitative factors that enhance tourists’ well-being, providing a reference for promoting the sustainable development of self-driving tourism.

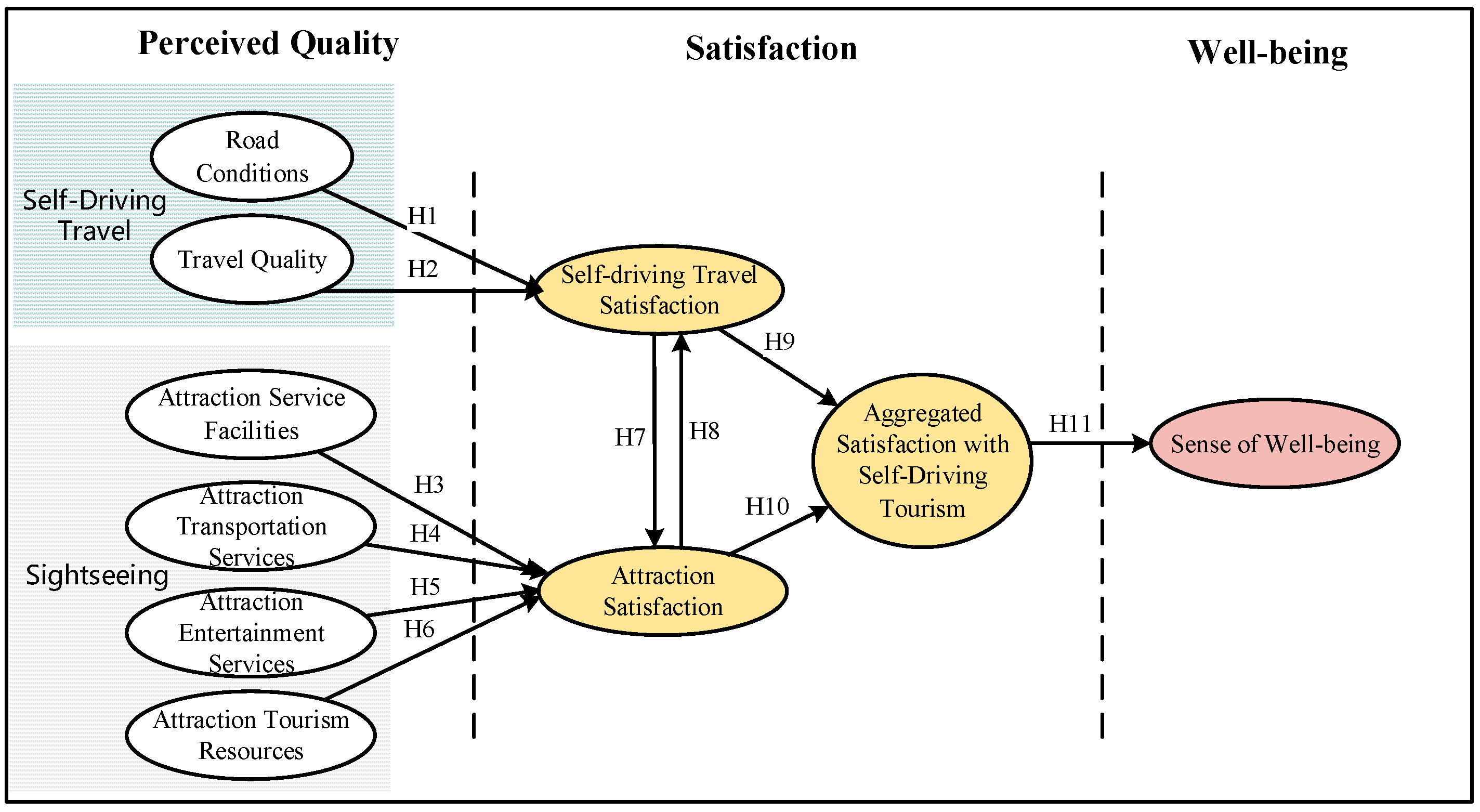

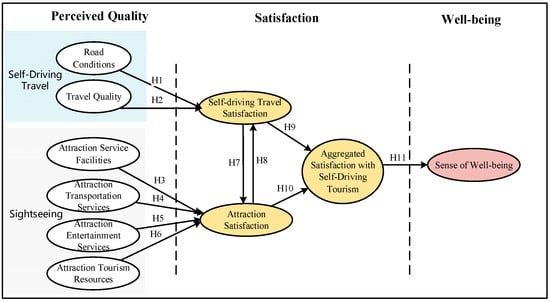

High perceived quality fosters positive travel experiences, which is a critical factor influencing satisfaction, while increased satisfaction enhances tourists’ happiness. To explore the mechanism by which self-driving tourism contributes to happiness, this paper employs a framework of “perceived quality—satisfaction—happiness” and proposes the following eleven hypotheses (H1–H11), as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research model of perceived quality and tourist happiness for self-driving tourists.

2.4. Basic Hypotheses of the Model

2.4.1. Impact of Perceived Quality on Self-Driving Tourist Satisfaction and Attraction Satisfaction

Research on tourism satisfaction is often based on the American Customer Satisfaction Index theoretical model. Studies have shown that higher perceived quality leads to greater tourist satisfaction (F. Chen et al., 2022). This paper retains the two indicators of perceived quality and customer satisfaction and conducts a multidimensional analysis of these indicators at two stages: attraction visits and self-driving travel.

F. Wu (2021) found that friendly road infrastructure is a significant indicator in the study of road tourism routes. Jiao and Zhou (2021) pointed out that factors such as the layout of gas stations and road signage, along with travel information concerning road conditions and weather, positively influence satisfaction. Hallo and Manning (2009) found that scenic distance to parks, traffic flow, opportunities for driving enjoyment, traffic signage, and speed limits were identified as important factors affecting driving enjoyment. Scenic byways play an important role in the driving experience (Shailes et al., 2001; Eby & Molnar, 2002). Avila-Foucat et al. (2013) noted that excessive crowds reduce satisfaction, thus considering the factor of road congestion. Shi et al. (2014) discovered that expenses on highways significantly impact self-driving satisfaction. Autonomous driving technology is viewed as an important means to enhance road safety and traffic efficiency, and the public generally holds a positive attitude toward its development.

J. Yang and Shen (2017) found that tourists with higher confidence in autonomous driving technology expect to be freed from driving tasks, allowing them to enjoy the scenery and have recreational experiences. Therefore, this paper incorporates the level of vehicle automation as a factor influencing the driving experience. The perceived factors related to self-driving travel are divided into two dimensions, road conditions and travel quality, resulting in the following hypotheses:

H1:

The road conditions in tourists’ perceived quality of self-driving significantly and positively influence self-driving satisfaction.

H2:

The travel quality in tourists’ perceived quality of self-driving significantly and positively influences self-driving satisfaction.

T. Y. Chen et al. (2021) found that the experience of service facilities significantly influences tourist satisfaction in national forest parks in Shandong Province. Huang (2023) identified that perceived quality of intelligent services and infrastructure had the most significant impact on satisfaction. Y. Zhang and Liu (2018) found that public services in tourist areas positively affect tourists’ satisfaction ratings. F. Chen (2023) found that transportation services positively affect visitor satisfaction in grassland tourism areas, indicating that tourists value tourist transportation services in tourist areas more, and that positive tourist transportation in tourist areas significantly affects tourists’ satisfaction. Ruan et al. (2018) summarized the evaluation categories of tourist satisfaction at West Lake into four types: supporting facilities, tourism transportation, entertainment services, and core attractions. Ge (2022) discovered that the quality of tourism products and dining in wetland parks positively influences satisfaction. Dax and Tamme (2023) found that attractive landscape features as drivers of sustainable mountain tourism experiences. Dong et al. (2020) and Y. J. Liu (2016) found that catering accommodation is a key factor influencing the assessment of tourists’ satisfaction. Perception of tourism resources is the largest latent variable affecting tourist satisfaction (J. Wu et al., 2022; Z. C. Liu & Qian, 2019). Based on these findings, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H3:

The service facilities in tourists’ perceived quality of attractions significantly and positively influence attraction satisfaction.

H4:

The transportation services in tourists’ perceived quality of attractions significantly and positively influence attraction satisfaction.

H5:

The entertainment offerings in tourists’ perceived quality of attractions significantly and positively influence attraction satisfaction.

H6:

The resources in tourists’ perceived quality of attractions significantly and positively influence attraction satisfaction.

2.4.2. Interrelationship Among Self-Driving Satisfaction, Attraction Satisfaction, and Overall Self-Driving Satisfaction

The transition from “travel separation” to “integrated travel” forms the basis of the overall self-driving satisfaction involving both self-driving and attraction experiences. Based on Q. Zhang (2020) multidimensional division of satisfaction, this study divides tourist satisfaction into self-driving satisfaction, attraction satisfaction, and overall self-driving satisfaction.

A positive travel experience during the self-driving phase can influence tourists’ initial impressions of attractions, thus affecting their overall satisfaction. Multi-destination is a distinctive feature of self-driving tourism, and it is believed that there is a cumulative effect of destination attractiveness in multi-destination tourism (Lue et al., 1996). Kahneman (2000) found that overall trip satisfaction is influenced by satisfaction at each stage and the relationship is in line with the peak-tail criterion. Gao (2018) argued that the lowest satisfaction among the stages of satisfaction can dominate the overall satisfaction. Studies have indicated that if any stage of the journey is perceived to enhance satisfaction, it positively impacts overall journey satisfaction, even if this enhancement is not applied to other stages (Suzuki et al., 2014). Thus, a smooth driving experience and a pleasant visit can enhance the overall satisfaction of self-driving tourism. Consequently, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H7:

Tourist self-driving satisfaction significantly influences attraction satisfaction.

H8:

Tourist attraction satisfaction significantly influences self-driving satisfaction.

H9:

Tourist self-driving satisfaction significantly and positively influences overall self-driving satisfaction.

H10:

Tourist attraction satisfaction significantly and positively influences overall self-driving satisfaction.

2.4.3. Impact of Overall Self-Driving Satisfaction on Tourist Well-Being

An increasing number of studies suggest that tourism, as a form of psychological therapy, can enhance tourist well-being. Tourist satisfaction is significantly positively correlated with subjective well-being (Meng, 2019). Y. R. Xu (2023) found that tourists’ satisfaction with sports and leisure towns directly and positively affects their subjective well-being. H. Wang and Ma (2020) explored the impact of travel motivation and satisfaction on subjective well-being in the context of cycling tourism along the Sichuan–Tibet route. Tourists can have a pleasurable emotional experience through tourism vacations and enhance their positive emotions, which affects their well-being (Niininen et al., 2004). Based on these findings, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H11:

Tourist overall self-driving satisfaction significantly and positively influences well-being.

3. Survey Design and Preliminary Analysis

3.1. Questionnaire Design

Based on the literature review, qualitative analysis, expert consultations, and preliminary data analysis, measurement indicators were determined. The questionnaire collected data on tourists’ travel experiences, demographic characteristics, and the study model, which involved ten latent variables related to perceived quality and tourist well-being among self-driving tourists. All latent variables were measured using a 5-point Likert scale, with corresponding measurement variables (Table A1). Data processing was conducted using SPSS 23.

3.2. Data Collection

The survey was commissioned to a professional research company and was conducted from 18 July to 2 August 2024. The survey sample utilized stratified sampling based on the age, occupation, and income distribution of self-driving travelers, resulting in a total of 625 responses, with an effective questionnaire recovery rate of 96%.

In terms of personal socio-economic attributes, the gender ratio was relatively balanced. The group with self-driving experience primarily consisted of families (74.20%) and was predominantly composed of well-educated young and middle-aged individuals (90.00% with higher education; 70.80% aged 30–50). The largest proportion of self-driving individuals were employed in private enterprises (52.20%), followed by civil servants and employees of state-owned enterprises, while retirees accounted for only 0.30%. The majority of respondents reported a personal monthly income between CNY 8001 and CNY 15,000 (40.80%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Personal socioeconomic attributes.

Statistics regarding self-driving travel experience indicated that most individuals drove fewer than five times a year. In the most recent self-driving trip, the highest proportion of respondents traveled with 2–5 people (86.20%), primarily as family outings (84.33%). The most common travel distance chosen was between 100 and 500 kilometers (69.50%), with only 9.20% opting for long-distance travel. Travelers showed the highest concern for information regarding attractions and accommodations, followed by crowding information. The primary reasons for self-driving travel included the freedom of movement, closeness to nature, and personalized experiences (Table 2).

Table 2.

Self-driving experience.

Regarding the most recent self-driving trip, although the majority chose fuel vehicles (71.70%), the usage of electric and hybrid vehicles approached 30%. The level of vehicle intelligence was predominantly at L1 and L2 levels (75.70%). Regardless of the vehicle type, self-driving travelers prioritized comfort during travel, interior space, and the convenience of charging/refueling station facilities (Table 3).

Table 3.

Recent self-driving information.

4. Model Testing and Result Analysis

4.1. Reliability and Validity Assessment of the Model

The most commonly used measure to assess reliability is the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the observed variables associated with each latent variable are all greater than 0.7, indicating that the scale exhibits good internal consistency and meets the reliability criterion.

For the validity assessment, this paper primarily examines the structural validity and convergent validity of the scale. Structural validity tests whether the correspondence between factors and measurement items aligns with expectations, with the primary method being exploratory factor analysis (EFA). The KMO value of the scale, calculated using SPSS software, is 0.937 (greater than 0.9), and the p-value of Bartlett’s sphere test is less than 0.005, indicating that the scale is suitable for factor analysis. During the pre-survey, uncharacteristic items, such as TQ5 and SWB6, were removed, with SWB6 deleted to avoid covariance with SWB7. The factor loadings of the 10 extracted factors were all greater than 0.5, and the cumulative variance explained was 70.474%, suggesting that the scale demonstrates good structural validity.

Convergent validity primarily refers to the extent to which measurement variables assessing the same construct are grouped within the same factor dimensions during testing. This is typically evaluated using three indicators: Standardized path coefficients, Composite reliability (CR), and Average variance extracted (AVE), all derived from Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA).

Based on the results of the preliminary survey, item TQ5, which was unable to represent the construct, was removed; additionally, item SWB6, which exhibited multicollinearity with SWB7, was also eliminated. The reliability, structural validity, and convergent validity of the measurement model were evaluated using Cronbach’s α coefficient, KMO value, standardized factor loadings, Composite Reliability (CR), and Average Variance Extracted (AVE). The scale meets the criteria for reliability and structural validity (Table 4).

Table 4.

Results of reliability and validity tests for latent variables.

Confirmatory factor analysis using AMOS 23.0 indicated that the standardized path coefficients for each item were greater than 0.5, and the CR for each latent variable exceeded 0.7, which met the requirements. All latent variables, except for road conditions, had AVE values greater than 0.5. Although the AVE for road conditions was 0.468, the CR was greater than 0.6 (Bagozzi, 1981) indicating that it still meets the criterion for convergent validity. Overall, the scale demonstrates good convergent validity.

Discriminant validity analysis revealed significant correlations between the latent variables. The values on the diagonal in the table represent the square roots of the average variance extracted (AVE) for each latent variable, all of which are greater than the Pearson correlation coefficients between the latent variables. It can be found that the obtained latent variables are both correlated and independent of each other, and the scale has a desirable discriminant validity (Table 5).

Table 5.

Results of discriminant validity test.

4.2. Hypothesis Testing and Parameter Estimation Results of the Model

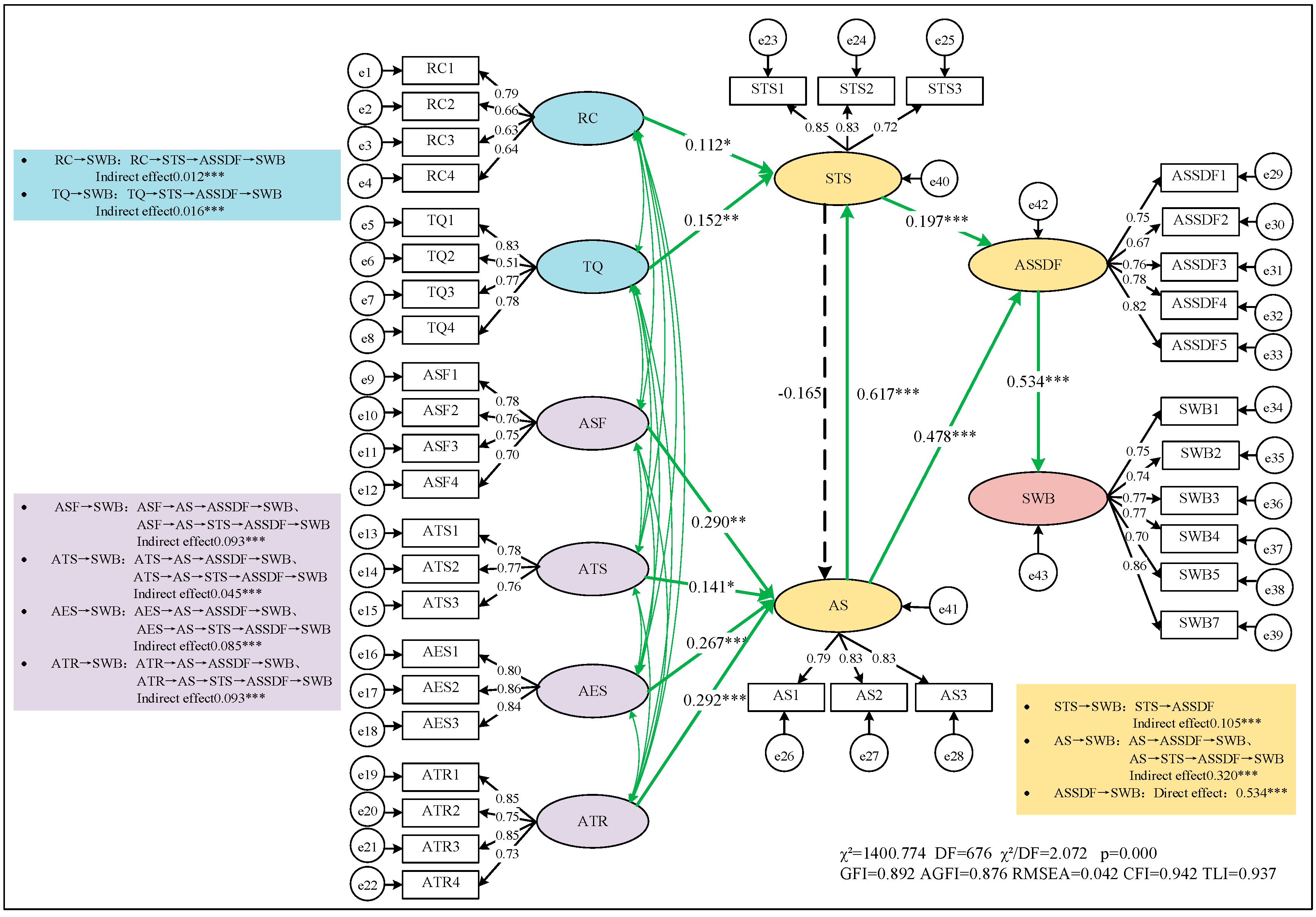

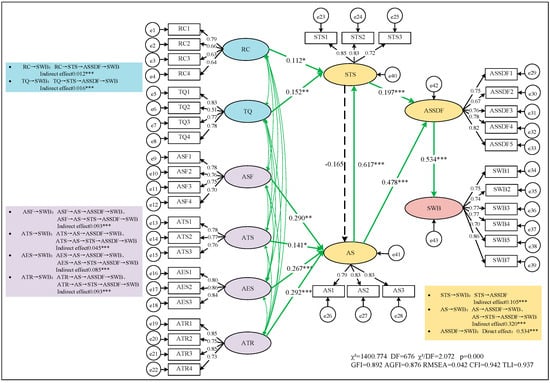

Based on the theoretical model constructed (Figure 1), a model fit analysis was conducted using Amos 23 software. The modified model obtained optimal fit results, with all indicators meeting standard value requirements except for the Goodness of Fit Index (GFI), which was 0.892, and the Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index (AGFI), which was 0.876, both of which are within acceptable ranges. Overall, the model demonstrated good fit (Table 6).

Table 6.

Degree of model fit.

The significance of the standardized path coefficients was assessed to evaluate the rationality of the hypotheses (Table 7). With the exception of the path from travel satisfaction to attraction satisfaction, which was not supported, all other hypothesized relationships were confirmed.

Table 7.

Results of hypothesis testing for the model.

4.3. The Mechanisms of Perceived Quality Impact on Tourist Happiness for Self-Driving Tourists

4.3.1. Tourist Satisfaction and Happiness

The overall satisfaction with the self-driving journey significantly impacts tourist happiness, followed by the indirect effects of attraction and travel satisfaction (Figure 2). Happiness originates from the comprehensive experience of the self-driving journey (ASSDF1, ASSDF5).

Figure 2.

Standardized parameter estimates of the SEM model (Covariance and residual coefficients are ignored). ***: p-value < 0.001, **: p-value < 0.01, *: p-value < 0.05.

Compared to travel satisfaction, attraction satisfaction has a more pronounced effect on tourist happiness and positively influences travel satisfaction, suggesting that attraction satisfaction modulates the travel experience and is a crucial factor in enhancing happiness. Given the significant correlation between travel expectations (STS1) and the discrepancy between actual and ideal sightseeing experiences (AS2) with tourist satisfaction, providing essential travel information and enhancing attraction appeal can help tourists form reasonable expectations and meet ideal travel conditions, thereby improving satisfaction.

4.3.2. Perceived Quality and Tourist Satisfaction

As a prerequisite for satisfaction, positive perceptions of perceived quality play a facilitative role. As shown in Figure 2, satisfaction with attractions is the most significant factor influencing overall satisfaction with self-driving trips. Tourists prioritize the attractions themselves over congestion information, and the attractions, as key points of the self-driving trip, positively moderate the self-driving experience.

Travel quality encompasses the overall assessment of the travel experience, including vehicle intelligence, scenic views, weather visibility, and congestion. Road conditions refer to the safety and comfort of driving surfaces and facilities. Travel quality has a greater impact than road conditions (Figure 2). Attraction satisfaction is most influenced by service facilities and tourism resources and is not affected by the self-driving experience of the current trip. This suggests that perceived quality across various dimensions of the self-driving journey positively influences tourist satisfaction (C. Zhang, 2025). On one hand, the supply of service resources at attractions remains crucial for ensuring overall satisfaction; on the other, road and attraction transportation services are indispensable for fulfilling travel satisfaction.

4.3.3. Perceived Quality and Tourist Happiness

According to the SOR (Stimulus-Organism-Response) theory, tourist satisfaction, stimulated by perceived quality, fosters a state of immersion that facilitates positive happiness (He et al., 2020). Attraction service facilities and tourism resources have the most significant impact on tourist happiness, followed by entertainment services (Figure 2). Attraction transportation services, travel quality, and road conditions have a lesser but still positive impact.

Visitors derive happiness from guide consultation facilities (ASF1), scenic attractiveness (ATR1), and the uniqueness of resources (ATR3). This is because self-driving tourists value attraction information, and diverse scenic resources offer new experiences (SWB3) and joy (SWB7). Given the prevailing “seeking pleasure” motivation, attractions must offer distinctive entertainment activities (AES1, AES2, AES3) to enhance happiness.

For self-driving tourists, the driving journey is an integral part of the trip. In terms of attraction transportation services, the construction of tourist parking lots and the moderate distance to entrances (ATS3) directly affect tourists’ impressions of attractions, with a particular concern for the number of parking spaces (ATS1). Regarding travel quality, vehicle intelligence (TQ1), scenic views (TQ3), and weather (TQ4) are significantly related. Among road conditions, road smoothness and driving safety (RC1) are the most important factors.

Since tourists seek freedom and closeness to nature, many drive L1 and L2 intelligent vehicles and prioritize driving comfort, the convenience of charging/fueling stations, road quality, safety, scenic route design, timely weather updates, and vehicle intelligence features. These factors significantly contribute to an immersive self-driving experience (SWB4) and a sense of accomplishment (SWB1), with family trips also enhancing intimacy among companions (SWB2).

Due to well-developed navigation and service facilities, tourists can predict congestion and focus less on parking costs, which form a small part of self-driving expenses, instead emphasizing satisfaction from the experience. Therefore, these factors have a limited correlation with perceived quality.

5. Discussion

Based on the whole process of self-driving tourism, this study investigates the effects of perceived quality and satisfaction on tourists’ well-being during the travel and attraction phases; it constructs a model illustrating the transmission mechanism of perceived quality–satisfaction–happiness. This study aligns with existing literature and offers a series of in-depth discussions grounded in previous research perspectives.

First, improving satisfaction in each segment of the self-driving tourism process significantly enhances tourists’ overall well-being. This finding is consistent with the conclusions of C. K. Liu et al. (2019), Kahneman (2000), Suzuki et al. (2014), and Gao (2018), who identified a positive correlation between satisfaction and well-being. Furthermore, the study reveals a positive correlation between tourists’ satisfaction with actual self-driving trips and their pre-trip expectations, supporting the view that tourists’ happiness is closely linked to pre-departure psychological expectations (Niininen et al., 2004; Nawijn et al., 2010). Building on the existing perspective that improving attraction satisfaction is a key pathway to enhancing self-driving tourists’ well-being (Sirgy et al., 2011), this study finds that attraction satisfaction has the most significant effect on tourists’ well-being and can influence the entire travel experience. Survey data show that tourists placed greater importance on the attractions themselves than on contextual factors such as traffic or road congestion. This suggests that, as core nodes in self-driving tourism, attractions play a dominant role in shaping the overall travel experience.

Second, when analyzing the perceived quality dimension within the whole process of self-driving tourism, it was found that, under the attraction perception dimension, self-driving tourists place considerable emphasis on attraction quality and service experience (Jiao & Zhou, 2021; H. B. Yu & Wu, 2011; Luo et al., 2016), as well as on characteristic indicators such as high involvement and personalization (Wager, 1967; Ren, 2017). This study found that, compared to the perceived quality of the self-driving component, elements such as attraction service facilities, leisure services, and tourism resources are the core aspects to which tourists pay the most attention. Therefore, key variables influencing perceived quality at attractions include tourism resource endowment, the provision of recreational programs, and service quality. Meanwhile, under the transportation perception dimension, travel-related quality factors—such as road conditions, the travel environment, and transportation facilities at attractions—also significantly affect tourist satisfaction. This suggests that the quality of the “on-the-road” experience constitutes an important component of overall satisfaction for self-driving tourists (Q. Yu et al., 2006; Shailes et al., 2001), aligning with their intrinsic enjoyment of the driving experience itself (Hallo & Manning, 2009). The results of this study not only complement previous research that has emphasized the service quality dimension at destinations but also broaden the research scope by incorporating the travel experience into the tourism service chain.

Furthermore, it was found that perceived quality indirectly affects well-being through satisfaction, which in turn triggers pleasure, immersion, and emotional connection with peers at the psychological level. This “emotional resonance” mechanism not only confirms Niininen et al.’s (2004) view that tourism vacations can lead to pleasurable emotional experiences, but also supports Y. Chen et al. (2017) conclusion that companionship significantly influences the tourism experience.

In this study on the perceived quality of attractions, it was found that, at the level of attraction services and facilities, guided counseling services indirectly and positively affect well-being. As self-driving tourists are often inexperienced and susceptible to unexpected situations, the provision of guided tour counseling serves as an important safeguard (Pan & Chen, 2015). At the level of attraction transportation facilities, the number of parking spaces, the quality of the parking environment, the distance to the entrance, and the comfort of the surrounding area all have a direct and positive impact on visitor well-being. In contrast to F. Chen’s (2023) findings, parking availability emerged as a particularly significant factor. At the level of attraction entertainment services (e.g., shows, dining, and shopping), such offerings indirectly enhance well-being (C. B. Zhang et al., 2015). Regarding attraction tourism resources, specialty resources and visual landscapes are key elements in attracting tourists (Y. Chen et al., 2017).

In this study’s examination of the perceived quality of self-driving experiences, it was found that, at the level of road conditions and trip quality, factors such as road safety, roadside scenery, and weather information are crucial for safeguarding the driving experience and enhancing travel happiness (Hu et al., 2020). Notably, positive feedback from tourists on the smart features of vehicles suggests that technological innovation holds significant promise for enhancing travel well-being (Y. Z. Wang et al., 2023; Dai, 2023; S. Ma, 2024). This finding offers a valuable complementary perspective for research in the fields of smart tourism and intelligent transportation.

The empirical results of this study not only validate the applicability of the theoretical framework but also offer a new research perspective for exploring the relationship between tourism happiness and the tourism process. The theoretical contributions of this study are primarily reflected in the following two aspects: (1) By focusing on the characteristics of self-driving tourism, this study constructs and verifies a three-stage model of “perceived quality–satisfaction–happiness”, which breaks through the limitations of traditional tourism research that typically analyzes happiness only at the destination level. This model expands the formation pathway of tourism happiness. (2) Through the use of a tourist-centered happiness scale, the study reveals the transmission mechanism by which self-driving satisfaction influences happiness. It provides a practical method for measuring the happiness of self-driving tourists and deepens the understanding of tourist happiness within the context of self-driving tourism, contributing theoretical significance to the field.

The practical contributions of this study are mainly reflected in the following two aspects: (1) This study organically integrates transportation and attraction visits to construct a holistic process-based scenario of self-driving tourism, thereby breaking through the traditional single-stage research paradigm. From the tourist’s perspective, the study systematically measures satisfaction across the entire self-driving tourism process, analyzes the transmission logic and interaction of satisfaction at each stage, clarifies the contribution weight of each segment to overall satisfaction, and identifies the core elements for enhancing tourist happiness. This provides a scientific basis for promoting the sustainable development of self-driving tourism. (2) Based on existing literature and travel review websites data, the perceived quality of self-driving tourism is further subdivided into six dimensions, covering both the travel and sightseeing stages. A quality assessment framework is thereby constructed for self-driving scenarios, enriching the application of research related to service quality and tourism satisfaction.

6. Research Conclusions, Implications, and Prospects

6.1. Research Conclusions

This study investigates the impact of perceived quality and tourist satisfaction on the happiness of self-driving tourists, focusing on the entire process of self-driving tours. It identifies the value of perceived quality in both the self-driving journey and sightseeing stages in enhancing tourist happiness. Perceived quality is divided into six dimensions: road conditions, travel quality, attraction service facilities, attraction transportation facilities, attraction entertainment services, and tourism resources. Tourist satisfaction is categorized into three dimensions: self-driving satisfaction, attraction satisfaction, and overall satisfaction with the self-driving process. These dimensions are linked to tourist happiness, forming a theoretical model to empirically study the influencing mechanisms. The key findings are as follows:

- Overall satisfaction with the self-driving process significantly affects tourist happiness (Direct effect = 0.534, p < 0.001), with a rich travel experience being crucial for enhancing happiness (C. K. Liu et al., 2019; Gao, 2018). Attraction satisfaction (Indirect effect = 0.320, p < 0.001) and self-driving satisfaction (Indirect effect = 0.5105, p < 0.001) also play important roles, with the former having a more notable indirect effect on happiness (Sirgy et al., 2011). While attraction satisfaction positively moderates the travel experience, the travel experience does not influence satisfaction derived from attractions.

- Perceived quality directly influences satisfaction with both the self-driving journey and attractions. Key elements, such as attraction service facilities (0.290, p < 0.001), entertainment services (0.267, p < 0.001), and tourism resources (0.292, p < 0.001), are critical for improving tourist satisfaction and meeting travel needs (Jiao & Zhou, 2021; Luo et al., 2016). Additionally, aspects of the self-driving experience, such as attraction transportation services (0.141, p < 0.05), travel quality (0.152, p < 0.01), and road conditions (0.112, p < 0.05), positively affect satisfaction (Q. Yu et al., 2006; Hallo & Manning, 2009).

- Perceived quality indirectly affects happiness through satisfaction, bringing joy (SWB7), immersive experiences (SWB4), and enhanced intimacy among travel companions (SWB2). The role of vehicle intelligence (TQ1) in boosting happiness is noteworthy. Enhancing core attraction appeal (ATR1, ATR3), guide services (ASF1), parking facilities (ATS1), and the surrounding environment (ATS3) are essential for increasing tourist happiness (Pan & Chen, 2015; C. B. Zhang et al., 2015; Y. Chen et al., 2017). Road safety, driving comfort, and scenic design also play significant roles. These factors should be considered in the layout of self-driving tourism resources to enhance the overall tourist experience (Hu et al., 2020; S. Ma, 2024).

6.2. Implications and Prospects

This study focuses on the needs of self-driving tourists, exploring how perceived quality and satisfaction in the self-driving and sightseeing stages impact happiness. Analyzing the entire self-driving experience helps identify factors that enhance tourist satisfaction and meet their needs for physical and mental well-being. It provides theoretical support for improving tourist happiness and offers insights for the sustainable development of self-driving tourism.

As the perceived quality within attractions influences both the enjoyment and travel experience, satisfaction throughout the self-driving process positively impacts tourist happiness. Therefore, tourism product providers should focus on improving the intrinsic value and quality of attractions to enhance tourist happiness. Natural beauty and rich historical culture are the core attractions, requiring preservation as a foundation for development to meet tourists’ wellness needs.

In terms of service facilities, the freedom and personalization of self-driving tours call for enhanced smart guides and information services to help tourists fully experience the attractions and handle unexpected situations. Entertainment services should focus on developing locally distinctive cultural products and integrating culture and tourism through digital means, offering diverse entertainment options, such as VR exhibitions and digital cultural products, to provide fresh experiences. Regarding parking services, efforts should be made to build eco-friendly and multi-level parking lots, improve new energy facilities, like charging stations, and promote smart parking services.

As smooth roads and a comfortable driving experience increase tourist happiness, improving rural roads and scenic routes, while also enhancing basic services, such as accommodations and dining, are crucial for meeting the immersive travel experience. Establishing scenic overlooks and rest areas, along with designing attractive landscapes, will further enrich the experience. Strengthening the integration of public information services and timely updates on road conditions, visitor flow warnings, and weather forecasts will help tourists set reasonable travel expectations.

Additionally, the intelligent features of vehicles enhance the comfort and convenience of driving, positively affecting the happiness of self-driving tourists. Future designs for more intelligent application scenarios will further enhance the driving experience and encourage more people to enjoy self-driving tours.

The limitations of this study lie in the varied effects of perceived quality on tourist happiness, influenced by objective factors such as travel distance and attraction characteristics, and subjective factors like tourists’ perceptions. Future research could delve deeper into the heterogeneity of self-driving tourism destinations, routes, and tourists’ perceived quality for a more comprehensive discussion.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft preparation, F.W.; writing—review and editing, H.Y. and M.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

In China, non-interventional studies such as surveys, questionnaires, and social media research typically do not require ethical approval. This is in accordance with the following legal regulations: Measures of People’s Republic of China (PRC) Municipality on Ethical Review; Measures for Ethical Review of Biomedical Research Involving People (revised in 2016); Measures of National Health and Wellness Committee on Ethical Review of Biomedical Research Involving People (Wei Scientific Research Development [2016] No.11).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SEM | Structural Equation Model |

| CR | Composite Reliability |

| AVE | Average Variance Extracted |

| RC | Road Conditions |

| TQ | Travel Quality |

| ASF | Attraction Service Facilities |

| ATS | Attraction Transportation Services |

| AES | Attraction Entertainment Services |

| ATR | Attraction Tourism Resources |

| STS | Self-driving Travel Satisfaction |

| AS | Attraction Satisfaction |

| ASSDF | Aggregated Satisfaction with Self-Driving Tourism |

| SWB | Sense of Well-being |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Description of latent variable items.

Table A1.

Description of latent variable items.

| Latent Variable | Measurement Items | Study |

|---|---|---|

| Road Conditions (RC) | I believe that the road surface is smooth and free of cracks, ensuring safety and comfort while driving (RC1). | F. Wu (2021); C. B. Zhang et al. (2015); Nie (2018) |

| I believe that the road alignment is smooth, providing a pleasant driving experience (RC2). | ||

| I believe that road signage and directional facilities are complete, with information being accurate and clear (RC3). | ||

| I believe that charging stations and gas stations along the route (service areas) are well-equipped and sufficient (RC4). | ||

| Travel Quality (TQ) | I believe that the degree of vehicle intelligence enhances driving comfort and overall experience (TQ1). | Jiao and Zhou (2021); F. Chen et al. (2023) |

| I believe that the duration of traffic congestion exceeds my expectations, negatively affecting my travel experience (TQ2). | ||

| I believe that the scenery along the route can alleviate fatigue, enhancing the comfort and visual experience of self-driving (TQ3). | ||

| I believe that good weather and clear visibility improve driving comfort and overall experience (TQ4). | ||

| I believe that the cost of self-driving travel is reasonable (TQ5). | ||

| Attraction Service Facilities (ASF) | I believe that the guiding and consultation facilities at the attractions are comprehensive and reliable (ASF1). | Dong and Zhang (2019) |

| I believe that the sanitation facilities at the attractions, such as restrooms and trash bins, are clean and convenient (ASF2). | ||

| I believe that the safety service facilities at the attractions are adequate (ASF3). | ||

| I believe that the electronic communication facilities at the attractions are in good condition (ASF4). | ||

| Attraction Transportation Services (ATS) | I believe that parking spaces at the attractions are sufficient and easily accessible (ATS1). | |

| I believe that the parking fees at the attractions are reasonable (ATS2). | ||

| I believe that the distance from the parking lot to the attraction entrance is moderate and the environment is comfortable (ATS3). | ||

| Attraction Entertainment Services (AES) | I am satisfied with the variety and cost-effectiveness of the attraction’s recreational activities (AES1). | Shi et al. (2014) |

| I am satisfied with the variety and cost-effectiveness of shopping opportunities at the attraction (AES2). | ||

| I am satisfied with the variety and cost-effectiveness of dining options at the attraction (AES3). | ||

| Attraction Tourism Resources (ATR) | I believe that the natural and cultural landscapes of the attraction are highly aesthetic (ATR1). | Zhou and Yang (2014) |

| I believe that the conservation status of the attraction’s tourism resources is good (ATR2). | ||

| I believe that the tourism resources at the attraction are distinctive and well-known (ATR3). | ||

| I believe that the pricing of entrance tickets at the attraction is quite reasonable (ATR4). | ||

| Self-Driving Satisfaction (STS) | My driving experience this time exceeded my expectations (STS1). | Cheng (2022) |

| My driving experience this time is close to my ideal travel experience (STS2). | ||

| Overall, I am satisfied with my choice of self-driving as a mode of travel (STS3). | ||

| Attraction Satisfaction (AS) | My experience at this attraction exceeded my expectations (AS1). | |

| My experience at this attraction is close to my ideal scenario (AS2). | ||

| Overall, I am satisfied with this attraction (AS3). | ||

| Overall Self-Driving Experience Satisfaction (ASSDF) | I believe that both the self-driving experience and the attraction visit are important (ASSDF1). | |

| I believe that the experience at the attraction has a greater impact on overall travel experience compared to the self-driving experience (ASSDF2). | ||

| This trip of “self-driving travel + attraction visit” met my expectations for travel (ASSDF3). | ||

| This trip of “self-driving travel + attraction visit” is very close to my ideal travel scenario (ASSDF4). | ||

| Overall, I am very satisfied with this trip of “self-driving travel + attraction visit” (ASSDF5). | ||

| Subjective Well-Being (SWB) | This self-driving trip gave me a sense of accomplishment (SWB1). | Tuo et al. (2020) |

| This self-driving trip enhanced my closeness with fellow travelers (SWB2). | ||

| This self-driving trip enriched my life experiences (SWB3). | ||

| During this self-driving trip, I felt a sense of freedom (SWB4). | ||

| The entire process of this self-driving trip was within my control (SWB5). | ||

| This self-driving trip helped me relax physically and mentally (SWB6). | ||

| This self-driving trip brought me joy (SWB7). |

References

- Akama, J. S., & Kieti, D. M. (2003). Measuring tourist satisfaction with Kenya’s wildlife safari: A case study of Tsavo West National Park. Tourism Management, 24(1), 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsiehemy, A. (2023). Events-based service quality and tourism sustainability: The mediating and moderating role of value-based tourist behavior. Sustainability, 15(21), 15303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avila-Foucat, V. S., Vargas, A. S., Jordan, A. F., & Flores, O. M. R. (2013). The impact of vessel crowding on the probability of tourists returning to whale watching in Banderas Bay, Mexico. Ocean & Coastal Management, 78, 12–17. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R. P. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: A comment. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(3), 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, D. A., & Crompton, J. L. (2000). Quality, satisfaction and behavioral intentions. Annals of Tourism Research, 27(3), 785–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F., Lu, G., Tan, H., Liu, M., & Wan, H. (2022). Effects of assignments of dedicated automated vehicle lanes and inter-vehicle distances of automated vehicle platoons on car-following performance of nearby manual vehicle drivers. Accident Analysis and Prevention, 177, 106826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F., Yu, M., Ji, X. F., Li, J., & Hao, X. (2023). Influence of traffic congestion perception on satisfaction and loyalty of holiday self-driving tour. Journal of Highway and Transportation Research and Development, 40(11), 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T. Y., Zhang, C. Y., Li, Y., & Xie, S. (2021). Research on tourist satisfaction on5A scenic spots in Hubei province based on the association rules. Resource Development & Market, 37(10), 1159–1165. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y., Tuo, Y. Y., Wu, D., & Zhang, T. (2020). The meaning of travel: From the perspective of tourists’ self-development. Human Geography, 35(5), 120–129. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y., Zhang, H., & Dong, M. L. (2017). Accompanying travelers matters? The impact of tourist-to-tourist interaction on tourists’ subjective well-being. Tourism Tribune, 32(8), 14–24. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, C. L. (2022). Research on tourist satisfaction of ice and snow tourism in Heilongjiang province based on structural equation model [Master’s thesis, Harbin University of Commerce]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J. C. (2023). Empirical analysis of usage intention and usage pattern of autonomous driving mobility service [Doctoral dissertation, Tsinghua University]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dax, T., & Tamme, O. (2023). Attractive landscape features as drivers for sustainable mountain tourism experiences. Tourism and Hospitality, 4(3), 374–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, N., & Zhang, C. H. (2019). Study of tourist satisfaction in a free forest park in the context of comprehensive tourism: A case of Wangshunshan in Shaanxi province. Tourism Tribune, 34(6), 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, N., Zhang, H., & Zhang, C. H. (2020). Tourist satisfaction of Shaanxi national forest park—A case study in Taibai, Taiping, and Wangshunshan. Scientia Silvae Sinicae, 56(3), 156–163. [Google Scholar]

- Eby, D. W., & Molnar, L. J. (2002). Importance of scenic byways in route choice: A survey of driving tourists in the United States. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 36(2), 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filep, S. (2012). Moving beyond subjective well-being: A tourism critique. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 38(2), 266–274. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y. N. (2018). Travel satisfaction and subjective well-being: A behavioral modeling perspective [Master’s thesis, Chang’an University]. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, G. Z. (2022). The relationship between perceived quality and satisfaction of visitors in urban wetland parks [Master’s thesis, Guizhou Normal University]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillet, S., Schmitz, P., & Mitas, O. (2013). The snap-happy tourist: The effects of photographing behavior on tourists’ happiness. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 40(1), 37–57. [Google Scholar]

- Grönroos, C. (1984). A service quality model and its marketing implications. European Journal of Marketing, 18(4), 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallo, J. C., & Manning, R. E. (2009). Transportation and recreation: A case study of visitors driving for pleasure at Acadia National Park. Journal of Transport Geography, 17(6), 491–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J. J. (2023). Research on the relationship between tourist-to-tourist interaction, tourism experience quality and tourists’ happiness—Take Wuhan Happy Valley Theme Park as an example [Doctoral dissertation, Hubei University]. [Google Scholar]

- He, X., Su, L., & Swanson, S. R. (2020). The service quality to subjective well-being of Chinese tourists’ connection: A model with replications. Current Issues in Tourism, 23(16), 2076–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heipke, C. (2010). Crowdsourcing geospatial data. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing, 65(6), 550–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W. X., Nie, J., & Jiang, H. (2020). Analysis of the influencing factors of tourists’ satisfaction of forest park in Guangzhou. Journal of Southwest Forestry University (Natural Sciences), 40(1), 147–152. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y. F. (2023). Analysis and empirical study on influential factors of tourist satisfaction of Yunnan smart tourism based on SEM [Master’s thesis, Yunnan University of Finance and Economics]. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, J. T., & Zhou, N. (2021). Research on self-drive tourists’ satisfaction based on scenic area supply in tourism area—A case study of Sayram Lake scenic area in Xinjiang. Journal of Baoji University of Arts and Sciences (Natural Science Edition), 41(4), 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D. (2000). Evaluation by moments: Past and future. In Choices, values, and frames (pp. 693–708). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W., Xu, H., & Li, Y. Y. (2020). Satisfaction of domestic self-driving tourists during holidays—Empirical analysis based on SEM. Journal of Henan Normal University (Natural Science Edition), 48(6), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C. K., Ren, F. R., & Wang, Z. X. (2019). Social capital, public service satisfaction and the subjective well-being. Journal of Capital University of Economics and Business, 21(4), 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. J. (2016). A comparative study on the influence factors of tourist satisfaction between the scenic spots in Zhangjiajie and Shaoshan. Economic Geography, 36(10), 216–221. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z. C., & Qian, Y. L. (2019). Study on tourist satisfaction of Wuling source ecological tourism scenic area based on SEM model. Social Sciences in Hunan, 2019(3), 121–127. [Google Scholar]

- Lue, C. C., Crompton, J. L., & Stewart, W. P. (1996). Evidence of cumulative attraction in multidestination recreational trip decisions. Journal of Travel Research, 35(1), 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H. M., Yu, Z. L., & Zhang, H. (2016). Tourists’ satisfaction and influencing factors in cultural and creative tourism destination for Tianzifang, M50 and Hongfang in Shanghai. Resources Science, 38(2), 353–363. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Q. F., Xia, Y. Y., & Xu, W. Z. (2017). A model of visitor-based destination brand equity of scenic spot. Commercial Research, 1, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S. (2024). Enhancing tourists’ satisfaction: Leveraging artificial intelligence in the tourism sector. Pacific International Journal, 7(3), 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q. L. (2019). Research on the relationship between rural tourism experience value and tourists’ well-being [Doctoral dissertation, Zhongnan University of Economics and Law]. [Google Scholar]

- Nawijn, J., Marchand, M. A., Veenhoven, R., & Vingerhoets, A. J. (2010). Vacationers happier, but most not happier after a holiday. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 5(1), 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, W. (2018). Empirical study on experience value and satisfaction of self-driving tourists in the expressway service area [Master’s thesis, Chongqing Jiaotong University]. [Google Scholar]

- Niininen, O., Gilbert, D., & Abdullah, J. (2004, February 10–13). An investigation of changes in well-being in relation to holiday taking. CAUTHE 2004: Creating Tourism Knowledge (pp. 123–135), Brisbane, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Y. F., & Chen, A. N. (2015). Study on the influencing factors on tourist satisfaction in Hangzhou’s historic districts. Journal of Zhejiang Shuren University (Social Sciences Edition), 15(2), 31–37. [Google Scholar]

- Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V., & Berry, L. (1988). SERVQUAL: A multiple-item scale for measuring consumer perceptions of service quality. Journal of Retailing, 64, 12–40. [Google Scholar]

- Pizam, A. (2005). Tourist consumer behavior. Dongbei University of Finance & Economics Press. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, W. T. (2022). The influence of rural tourism public service on tourists’ behavioral intention after travel—Based on the mediating role of well-being, sense of gain and Sense of security [Master’s thesis, Shanxi University of Finance and Economics]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z. Y. (2017). A study on the behavior characteristics of self-driving tourists in Gansu [Doctoral dissertation, Northwest Normal University]. [Google Scholar]

- Ruan, Y. C., Fang, Y., & Wen, Q. (2018). Evaluation system construction for tourist sites based on reviews data—In case of Xihu, Hangzhou. In Chinese Society for Urban Studies & Hangzhou Municipal People’s Government (Eds.), Shared and quality—Proceedings of the 2018 Chinese urban planning annual conference (05 urban planning new technology application) (pp. 402–411). School of Civil Engineering and Architecture, Zhejiang University. [Google Scholar]

- Shailes, A., Senior, M. L., & Andrew, B. P. (2001). Tourists’ travel behavior in response to congestion: The case of car trips to Cornwall, United Kingdom. Journal of Transport Geography, 9(1), 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, P. Y., Wan, D. M., & Li, J. X. (2023). The influence of tourism public service quality on tourists’ well-being: From the perspective of tourism experience. Tourism and Hospitality Prospects, 7(2), 22–54. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, C. Y., Sun, Y., Zhang, H. L., Liu, Z. H., & Lin, J. (2014). Study on the self-drive tourists’ satisfaction based on structural equation model. Geographical Research, 33(4), 751–761. [Google Scholar]

- Sirgy, M. J., Kruger, P. S., Lee, D. J., & Yu, G. B. (2011). How does a travel trip affect tourists’ life satisfaction? Journal of Travel Research: The International Association of Travel Research and Marketing Professionals, 50(3), 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- State Council of the People’s Republic of China. (2021). Notice on issuing the 14th five-year plan for tourism development (Guofa [2021] No. 32). Available online: https://www.ndrc.gov.cn/fggz/fzzlgh/gjjzxgh/202203/t20220325_1320209_ext.html (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- Suvittawat, A. (2024). Exploring customer experience drivers in night markets: Examining the roles of product preference, service quality, and facility accessibility. Tourism and Hospitality, 5(4), 1477–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, H., Fujii, S., Gärling, T., Ettema, D., Olsson, L. E., & Friman, M. (2014). Rules for aggregated satisfaction with work commutes. Transportation, 41(3), 495–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuo, Y. Y. (2015). Why is tourists’ well-being important? Tourism Tribune, 30(11), 16–18. [Google Scholar]

- Tuo, Y. Y., Bai, C. H., & Wang, L. (2020). Tourist well-being: Conceptualization and scale development. Nankai Business Review, 23(6), 166–178. [Google Scholar]

- Wager, J. (1967). Outdoor recreation on common land. Journal of the Town Planning Institute, 53, 398–499. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B., Yang, Z., Han, F., & Shi, H. (2017). Car tourism in Xinjiang: The mediation effect of perceived value and tourist satisfaction on the relationship between destination image and loyalty. Sustainability, 9(1), 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H., & Ma, Z. X. (2020). A study on tourist motivation of cycling tourism on the Sichuan-Tibet line and its impact on the cyclers’ happiness: The mediating effect of tourist satisfaction. Tourism Science, 34(6), 53–65. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X. R., & Sun, J. X. (2019). Urban residents’ leisure and subjective well-being: Evidences from Guangzhou, China. Geographical Research, 38(7), 1566–1580. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y. Z., Li, Y. J., & Tang, L. (2023). Modeling and analysis of autonomous driving acceptance by transportation practitioners. Journal of Transportation Engineering and Information, 21(2), 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, W. R. (1967). Correlates of avowed happiness. Psychological Bulletin, 67(4), 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Tourism Organization. (1980). Manila declaration on world tourism. World Tourism Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, F. (2021). Research on the optimization of nu river beautiful highway tourism routes based on self-driving tour friendliness system [Master’s thesis, Yunnan Normal University]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J., Li, Q. B., Hu, Z. Y., & Liu, Y. (2022). Analyzing tourist satisfaction of rural scenic attractions based on IPA model. Data Analysis and Knowledge Discovery, 29(12), 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, C. X., & Zheng, J. (2021). The relationship between the role of travel companions, traveling experience quality and tourists’ sense of happiness. Journal of Xiangtan University (Philosophy and Social Sciences), 45(5), 69–73. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y. R. (2023). The influence of service quality of sports and leisure town on tourists subjective well-being [Master’s thesis, Shanghai University of Sport]. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, R. G., Zhou, S. H., & Yan, X. P. (2011). Research on urban renewal. Progress in Geography, 30(8), 947–955. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J., & Shen, M. J. (2017). Investigation of consumer market acceptance of automated vehicles in China. Journal of Chang’an University (Social Science Edition), 19(6), 34–42. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J. Y. (2022). Urban suburban tourism route planning based on tourist satisfaction [Master’s thesis, Chongqing Jiaotong University]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H. B., & Wu, B. H. (2011). Progress about the study of overseas self-driving travel. Tourism Tribune, 26(3), 55–61. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Q., Fan, X., & Liu, Z. M. (2006). On the principle and applications of scenic byways abroad. Tourism Tribune, 21(5), 91–96. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C. (2018). Research on evaluation system of tourist perception of military reclamation museum based on factor analysis—A case study on museum of Xinjiang bingtuan army reclamation. Resource Development & Market, 34(3), 433–438. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C. (2025). Research on the evaluation method of urban public bus transportation oriented to service [Doctoral dissertation, Tongji University]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C. B., Chen, X. H., Li, D. J., & Zhang, C. (2015). A research on tourist satisfaction based on the formative measurement model—Comparing individual with group tours. Journal of Arid Land Resources and Environment, 29(10), 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q. (2020). A study on the relationship between the tourists’ perceived crowding and their satisfaction in theme parks—The case of Zhengzhou fantawild adventure [Master’s thesis, Henan University]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., Liu, M., & Bai, C. H. (2020). Research on the elements of Tourists’ well-being from a naturalism perspective. Tourism Tribune, 35(5), 37–51. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y., & Liu, J. G. (2018). Domestic tourist’s satisfaction with Beijing natural scenic spots. Journal of Arid Land Resources and Environment, 32(11), 202–208. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X. J., & Yang, Y. (2014). Research of relation between casual summer tourists’ satisfaction and loyalty based on structural equation model—A case study of Huangshui Town, Chongqing City. Resource Development & Market, 30(2), 231–234. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).