Risk and Resilience in Tourism: How Political Instability and Social Conditions Influence Destination Choices

Abstract

1. Introduction

- To what extent do political instability and social conditions influence travelers’ destination choices?

- How do risk perceptions vary across different traveler demographics (e.g., age, gender, travel experience) when evaluating politically and socially unstable destinations?

- What role does media coverage play in shaping tourists’ risk perceptions and influencing destination selection?

- How can destination managers, tourism policymakers, and hospitality businesses mitigate negative risk perceptions and enhance tourism resilience in politically and socially unstable regions?

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Tourism and Perceived Risk

2.2. The SARF Model

2.3. Determinants of Tourism Demand

2.4. Tourism and Social Factors

2.5. Tourism and Political Factors

2.6. Hypotheses Discussion

2.6.1. Economic Crises, Political Instability, and Terrorism

2.6.2. Recreation, Safety, Municipal Facilities, and Services

2.6.3. Gender and Perception of Tourism Risks

3. Materials and Methods

- To measure the influence of social factors on visitors’ travel intentions and risk perception;

- To assess the impact of political instability on visitors’ travel intentions and risk perception;

- To determine the role of gender and other demographic characteristics in shaping travel intentions related to these factors.

- To explore how media coverage influences risk perception and destination choice.

- The research questions were formulated to align with the research aim;

- The study sample was defined based on the number of participants;

- The research tool (questionnaire) was structured to assess demographic factors, travel behavior, political factors, social conditions, and risk perception;

- The questionnaire was distributed electronically to the participants;

- Responses were entered into SPSS for statistical analysis;

- The necessary statistical analyses were conducted, and the resulting data were interpreted.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.1.1. Demographic Data

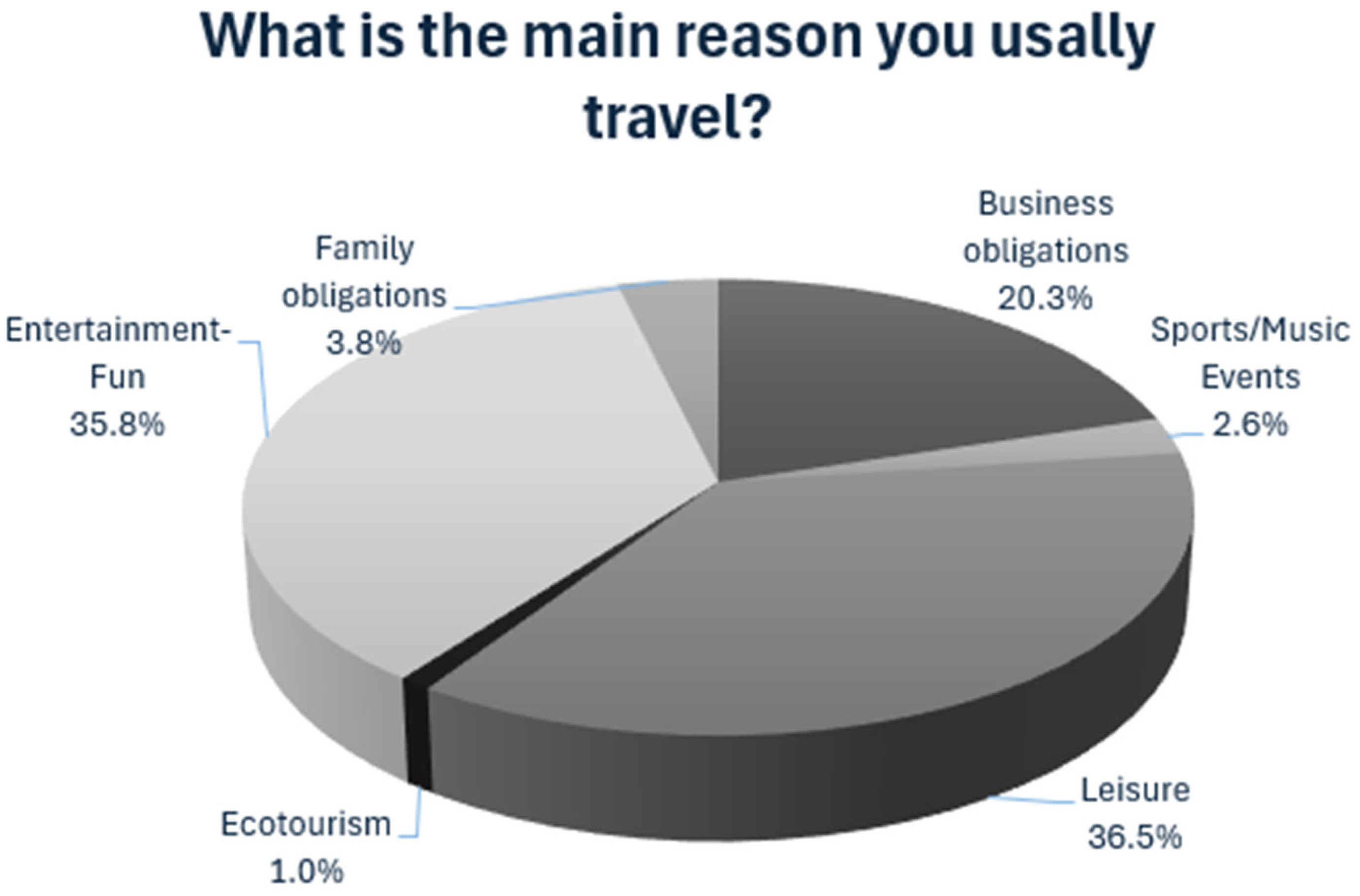

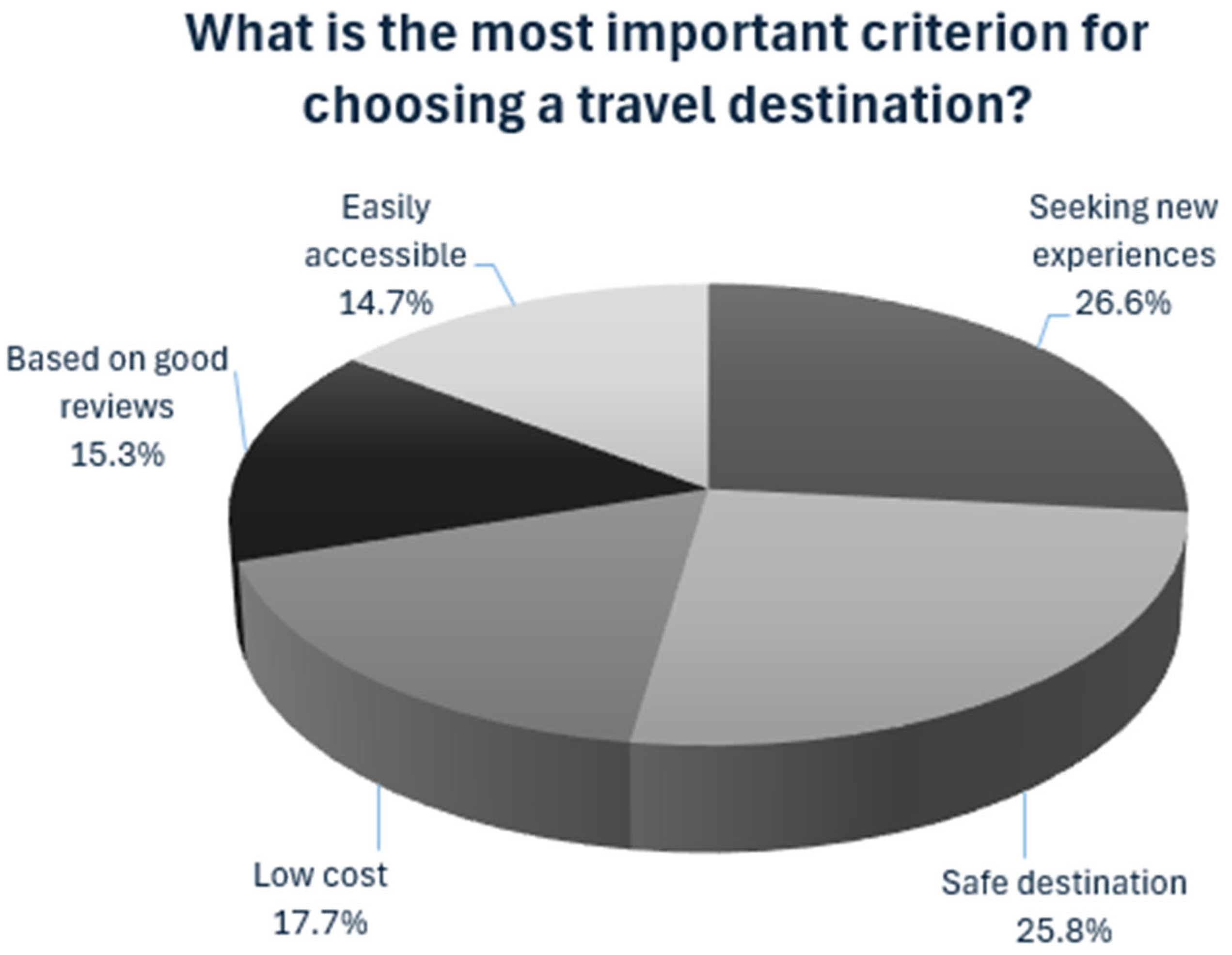

4.1.2. Tourist Habits

4.1.3. Political and Social Factors

4.2. Inferential Statistics

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alvarez, M. D., & Korzay, M. (2008). Influence of politics and media in the perceptions of Turkey as a tourism destination. Tourism Review, 63(2), 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelou, I., Katsaounidou, A., & Papadopoulou, L. (2022). Crisis as emotional labour in the news. Assessing the trauma frame during the economic and the pandemic crisis. Studies in Media and Communication, 10(2), 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelou, I., Katsaras, V., Kourkouridis, D., & Veglis, A. (2024). Social media metrics as predictors of publishers’ website traffic. Journalism and Media, 5(1), 281–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelou, I., & Veglis, A. (2024). Greek legacy media organizations in the digital age: A historical perspective of web tool adoption (1990s–2023). Internet Histories, 8(3), 229–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avraham, E., & Ketter, E. (2008). Media strategies for marketing places in crisis (1st ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avraham, E., & Ketter, E. (2016). Destination marketing during and following crises: Combating negative images in Asia. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 34(6), 709–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badoc-Gonzales, B. P., Mandigma, M. B. S., & Tan, J. (2022). SME resilience as a catalyst for tourism destinations: A literature review. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, 12(1), 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S. Y., & Chang, P. J. (2021). The effect of coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) risk perception on behavioural intention towards ‘untact’ tourism in South Korea during the first wave of the pandemic (March 2020). Current Issues in Tourism, 24(7), 1017–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bank of Greece. (2023). Travel services balance of payments statistics. Available online: https://www.bankofgreece.gr/en/statistics/external-sector/balance-of-payments/travel-services (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Becken, S., Jin, X., Zhang, C., & Gao, J. (2017). Urban air pollution in China: Destination image and risk perceptions. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(1), 130–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beirman, D. (2003). Restoring tourism destinations in crisis: A strategic marketing approach (1st ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beldona, S., Nusair, K., & Demicco, F. (2009). Online travel purchase behavior of generational cohorts: A longitudinal study. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 18(4), 406–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blešić, I., Ivkov, M., Tepavčević, J., Popov Raljić, J., Petrović, M. D., Gajić, T., Tretiakova, T. N., Syromiatnikova, J. A., Demirović Bajrami, D., Aleksić, M., Vujačić, D., Kričković, E., Radojković, M., Morar, C., & Lukić, T. (2022). Risky travel? Subjective vs. Objective perceived risks in travel behaviour—Influence of hydro-meteorological hazards in South-Eastern Europe on Serbian tourists. Atmosphere, 13(10), 1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braje, I. N., Dumančić, K., & Hruška, D. (2022). Building resilience in times of global crisis: The tourism sector in Croatia. European Political Science, 22(3), 406–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouder, P. (2020). Reset redux: Possible evolutionary pathways towards the transformation of tourism in a COVID-19 world. Tourism Geographies, 22(3), 484–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casado-Aranda, L., Sánchez-Fernández, J., & Manzano, A. B. B. (2021). Tourism research after the COVID-19 outbreak: Insights for more sustainable, local and smart cities. Sustainable Cities and Society, 73, 103126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherian, A. M., & Natarajamurthy, P. (2024). Rethinking tourism post-COVID: A public health perspective. South Eastern European Journal of Public Health, XXVI, 66–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, E. Y. T., & Jahari, S. A. (2014). Destination image as a mediator between perceived risks and revisit intention: A case of post-disaster Japan. Tourism Management, 40, 382–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, S. P., & Lin, Y. S. (2011). Study on risk representations of international tourists in India. African Journal of Business Management, 5(7), 2742–2752. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, C., Fletcher, J., Fyall, A., Gilbert, D., & Wanhil, S. (2008). Tourism: Principles and practice. Prentice Hall Financial Times. [Google Scholar]

- Farhangi, S., & Alipour, H. (2021). Social media as a catalyst for the enhancement of destination image: Evidence from a Mediterranean destination with political conflict. Sustainability, 13(13), 7276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faulkner, B., & Vikulov, S. (2001). Katherine, washed out one day, back on track the next: A post-mortem of a tourism disaster. Tourism Management, 22(4), 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzsimons, G. J., & Morwitz, V. G. (1996). The effect of measuring intent on brand-level purchase behavior. Journal of Consumer Research, 23(1), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floyd, M. F., Gibson, H., Pennington-Gray, L., & Thapa, B. (2004). The effect of risk perceptions on intentions to travel in the aftermath of September 11, 2001. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 15(2–3), 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goeldner, C. R., & Ritchie, J. R. (2011). Tourism: Principles, practices, philosophies (12th ed.). John Wiley and Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, W., & Liu, T. (2024). Research on the sustainable development of urban tourism economy: A perspective of resilience and efficiency synergies. Sage Open, 14(3), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafson, P. (2006). Work-related travel, gender, and family obligations. Work, Employment and Society, 20(3), 513–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellenic Statistical Authority. (2023). Arrivals and overnight stays in hotels, similar establishments, and campsites. Available online: https://www.statistics.gr/en/statistics/-/publication/STO12/ (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- IBIS World. (2021). Industry statistics-global. Available online: https://www.ibisworld.com/global/market-size/global-tourism/ (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Kapuscinski, G., & Richards, B. (2016). News framing effects on destination risk perception. Tourism Management, 57, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasperson, R. E., Renn, O., Slovic, P., Brown, H. S., Emel, J., Goble, R., Kasperson, J. X., & Ratick, S. (1988). The social amplification of risk: A conceptual framework. Risk Analysis, 8(2), 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. Y. (2005). “Bowling Together” isn’t a cure-all: The relationship between social capital and political trust in South Korea. International Political Science Review, 26(2), 193–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostopoulou, E., Avdimiotis, S., & Kourkouridis, D. (2022). The trade fair industry in transition: Digital, physical and hybrid trade fairs. The case of thessaloniki. In International conference of the international association of cultural and digital tourism (pp. 399–415). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourkouridis, D., Salepaki, A., Frangopoulos, I., Pozrikidis, K., & Dalkrani, V. (2024). Social exchange and destination loyalty: The case of thessaloniki international fair and the concept of honored countries. Event Management, 28(7), 971–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagos, D. (2018). Tourism planning and policy. Kritiki Editions. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Mansfeld, Y. (2006). The role of security information in tourism crisis management: The missing link. In Y. Mansfeld, & A. Pizam (Eds.), Tourism, security and safety (pp. 271–290). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- McKinsey & Company. (2024). The state of tourism and hospitality 2024. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/travel/our-insights/the-state-of-tourism-and-hospitality-2024#/ (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- McKinsey Global Institute. (2019). Globalization in transition: The future of trade and value chains. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/innovation-and-growth/globalization-in-transition-the-future-of-trade-and-value-chains (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Medová, N., Macková, L., & Harmacek, J. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 on hospitality industry in Greece and its treasured Santorini Island. Sustainability, 13(14), 7906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milne, S., & Ateljevic, I. (2001). Tourism, economic development and the global-local nexus: Theory embracing complexity. Tourism Geographies, 3(4), 369–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngoc, K. M., & Trinh, N. T. (2015). Factors affecting tourists’ return intention towards Vung Tau City, Vietnam-A mediation analysis of destination satisfaction. Journal of Advanced Management Science, 3(4), 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen Viet, B., Dang, H. P., & Nguyen, H. H. (2020). Revisit intention and satisfaction: The role of destination image, perceived risk, and cultural contact. Cogent Business & Management, 7(1), 1796249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2024). OECD tourism trends and policies 2024. OECD Publications. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, D. (1995). Tourism today: A geographical analysis (2nd ed.). Longman Scientific & Technical. [Google Scholar]

- Poon, A., & Adams, E. (2000). How the British will travel 2005. International Bielefeld. [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard, A., & Morgan, N. J. (2001). Culture, identity, and tourism representation: Marketing Cymru or Wales? Tourism Management, 22(2), 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H., & Nunkoo, R. (2011). City image and perceived tourism impact: Evidence from Port Louis, Mauritius. International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Administration, 12(2), 123–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, L. K. (1992). Political instability and tourism in the Third World, 35–46. Available online: https://www.cabdirect.org/cabdirect/abstract/19921896801 (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Ritchie, B. W., Dorrell, H., Miller, D., & Miller, G. A. (2004). Crisis communication and recovery for the tourism industry: Lessons from the 2001 foot and mouth disease outbreak in the United Kingdom. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 15(2–3), 199–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rittichainuwat, B. N., & Chakraborty, G. (2009). Perceived travel risks regarding terrorism and disease: The case of Thailand. Tourism Management, 30(3), 410–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahrabani, S., Rosenboim, M., Shavit, T., Benzion, U., & Arbiv, M. (2019). “Should I stay or should I go?” Risk perceptions, emotions, and the decision to stay in an attacked area. International Journal of Stress Management, 26(1), 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakeela, A., & Becken, S. (2015). Understanding tourism leaders’ perceptions of risks from climate change: An assessment of policy-making processes in the Maldives using the social amplification of risk framework (SARF). Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 23(1), 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoemaker, S. (1994). Segmenting the U.S. travel market according to benefits realized. Journal of Travel Research, 32(3), 8–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smeral, E. (1998). The impact of globalization on small and medium enterprises: New challenges for tourism policies in European countries. Tourism Management, 19(4), 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sönmez, S. F., Apostolopoulos, Y., & Tarlow, P. (1999). Tourism in crisis: Managing the effects of terrorism. Journal of Travel Research, 38(1), 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sönmez, S. F., & Graefe, A. R. (1998). Influence of terrorism risk on foreign tourism decisions. Annals of Tourism Research, 25(1), 112–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, L., Peng, F., & Wu, S. (2022). Spatio-temporal evolution of the resilience of chinese border cities. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 1101799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundar, S. S., & Nass, C. (2001). Conceptualizing sources in online news. Journal of Communication, 51(1), 52–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, C. C., Cheng, Y. J., Yen, W. S., & Shih, P. Y. (2023). COVID-19 perceived risk, travel risk perceptions and hotel staying intention: Hotel hygiene and safety practices as a moderator. Sustainability, 15(17), 13048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theocharous, A. L. (2010). A contextual typology for the study of the relationship between political instability and tourism. International Journal of Tourism Policy, 3(4), 354–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomczewska-Popowycz, N., & Quirini-Popławski, Ł. (2021). Political instability equals the collapse of tourism in ukraine? Sustainability, 13(8), 4126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, V. K., & Rajagopal, P. (2019). Analyzing factors affecting tourism sustainable development towards Vietnam in the new era. European Journal of Business and Innovation Research, 7(1), 30–42. [Google Scholar]

- University of Minnesota. (2016). The elements of culture in introduction to sociology: Understanding and changing the social world. University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- UNWTO. (2022). Tourism—An economic and social phenomenon: Why tourism? United Nations World Tourism Organization. [Google Scholar]

- UNWTO. (2024). Global tourism set for full recovery by end of the year with spending growing faster than arrivals. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/news/global-tourism-set-for-full-recovery-by-end-of-the-year-with-spending-growing-faster-than-arrivals (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Ushakov, D., & Andreeva, E. (2021). Multiplier and accumulating uselessness as new reality of tourism economy under pandemic. GeoJournal of Tourism and Geosites, 39(4spl), 1363–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wibowo, J. M., & Hariadi, S. (2022). Indonesia sustainable tourism resilience in the COVID-19 pandemic era: Case study of five indonesian super-priority destinations. Millennial Asia, 15(2), 236–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Economic Forum. (2019). The travel & tourism competitiveness report 2019: Travel and tourism at a tipping point. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/reports/the-travel-tourism-competitiveness-report-2019 (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Yang, Y. C., Boen, C., Gerken, K., Li, T., Schorpp, K., & Harris, K. M. (2016). Social relationships and physiological determinants of longevity across the human life span. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(3), 578–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H., Liu, J., Wei, Z., Li, W., & Wang, L. (2017). Residents’ attitudes towards sustainable tourism development in a historical-cultural village: Influence of perceived impacts, sense of place and tourism development potential. Sustainability, 9(1), 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 138 | 49.3% |

| Female | 142 | 50.7% | |

| Age | 18–25 | 18 | 6.4% |

| 26–35 | 76 | 27.1% | |

| 36–45 | 121 | 43.2% | |

| 46–60 | 51 | 18.2% | |

| 61 and over | 14 | 5.0% | |

| Marital status | Single | 103 | 36.8% |

| Married | 156 | 55.7% | |

| Divorced/Widowed | 21 | 7.5% | |

| Educational level | Primary Education | 4 | 1.4% |

| Secondary Education | 29 | 10.4% | |

| Higher Education | 123 | 43.9% | |

| Postgraduate Education (MSc, Ph.D.) | 124 | 44.3% | |

| Employment Status | Student | 12 | 4.3% |

| Public Sector Employees | 22 | 7.9% | |

| Private Sector Employees | 210 | 75.0% | |

| Self-Employed/Business Owners | 17 | 6.1% | |

| Unemployed | 8 | 2.9% | |

| Homemakers | 3 | 1.1% | |

| Retired | 8 | 2.9% | |

| Variables | Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| How many trips abroad have you made in the last 5 years? | None | 58 | 20.7% |

| 1–2 | 103 | 36.8% | |

| 3–5 | 71 | 25.4% | |

| 6+ | 48 | 17.1% | |

| Who do you usually travel with? | Alone | 26 | 9.3% |

| With partner/spouse | 103 | 36.8% | |

| With friends | 70 | 25.0% | |

| With family | 77 | 27.5% | |

| In organized tours (group) | 4 | 1.4% | |

| What type of accommodation do you usually stay in? | Hotel | 203 | 72.5% |

| Rented accommodation (Airbnb) | 45 | 16.1% | |

| Shared rooms (hostel) | 9 | 3.2% | |

| With relatives or friends | 23 | 8.2% | |

| Political Factors | Mean | Std. Dev. |

|---|---|---|

| 3.61 | 0.78 | |

| Avoiding travel to countries with unstable economic conditions | 3.03 | 1.09 |

| Avoiding travel to destinations with potential health risks | 4.32 | 0.90 |

| Avoiding travel to destinations with political instability | 3.80 | 1.10 |

| Avoiding travel to destinations that experienced a terrorist attack in the current year | 3.83 | 1.14 |

| Avoiding travel to destinations with potential risks of earthquakes or other natural disasters | 3.09 | 1.21 |

| Given the opportunity to travel abroad | 3.58 | 0.91 |

| Avoiding destinations with travel advisories for safety concerns | 3.96 | 1.14 |

| Avoiding destinations with travel advisories for health risks (e.g., flu) | 4.10 | 1.03 |

| Avoiding destinations with travel advisories for potential natural disasters | 3.68 | 1.20 |

| Avoiding destinations that recently experienced a terrorist attack | 3.60 | 1.24 |

| Avoiding destinations with unstable economic conditions | 2.85 | 1.16 |

| Avoiding destinations with political instability | 3.31 | 1.17 |

| Intent to travel to specific destinations | ||

| Israel | 2.71 | 1.33 |

| Turkey | 2.78 | 1.27 |

| Mexico | 3.20 | 1.38 |

| Egypt | 3.26 | 1.24 |

| Russia | 2.79 | 1.45 |

| If you are unwilling to travel to a destination, please assess the importance of the following conditions | 3.69 | 0.78 |

| High likelihood of a terrorist attack | 3.95 | 1.18 |

| Health risks | 4.12 | 1.04 |

| High crime rate | 4.08 | 0.98 |

| Destination is quite expensive | 3.55 | 1.09 |

| Risk of earthquakes or other natural disasters | 3.21 | 1.18 |

| High likelihood of social unrest | 3.57 | 1.07 |

| Political instability | 3.34 | 1.10 |

| Overall | 3.69 | 0.78 |

| Please Evaluate the Following Factors Regarding Your Place of Residence | Mean | Std. Dev. |

|---|---|---|

| Quality of facilities | 3.48 | 0.70 |

| Adequate night lighting | 3.75 | 0.93 |

| Availability of public transportation | 3.33 | 1.26 |

| Good road network and sidewalks | 3.29 | 1.17 |

| Easy access to local services (e.g., police) | 3.51 | 1.06 |

| Green spaces | 3.24 | 1.08 |

| Cleanliness | 3.69 | 1.03 |

| Low air pollution | 3.57 | 1.12 |

| Entertainment | 3.43 | 0.82 |

| Tourist facilities (e.g., accommodations, restaurants) | 3.62 | 1.08 |

| Proximity to major cities | 4.05 | 0.95 |

| Nightlife | 3.14 | 1.20 |

| Children’s activity centers | 2.91 | 1.33 |

| Safety | 3.96 | 0.80 |

| Quietness | 3.79 | 1.04 |

| Security | 4.22 | 0.88 |

| Low crime rate | 4.12 | 0.91 |

| Reduced overcrowding | 3.71 | 1.10 |

| Provided Services | 3.49 | 0.87 |

| Sufficient bank branches—ATMs | 3.52 | 1.14 |

| Numerous retail shops | 3.19 | 1.12 |

| Adequate healthcare facilities | 3.32 | 1.25 |

| Supermarkets in convenient locations | 3.91 | 0.99 |

| Social Factors Regarding the Choice of Tourist Destination | ||

| Quality of facilities | 3.79 | 0.68 |

| Adequate night lighting | 3.66 | 1.00 |

| Availability of public transportation | 4.03 | 0.95 |

| Good road network and sidewalks | 3.71 | 0.99 |

| Easy access to local services (e.g., police) | 3.61 | 1.03 |

| Green spaces | 3.74 | 0.95 |

| Cleanliness | 4.27 | 0.82 |

| Low air pollution | 3.52 | 0.99 |

| Entertainment | 3.29 | 0.76 |

| Tourist facilities (e.g., accommodations, restaurants) | 4.34 | 0.84 |

| Proximity to major cities | 3.68 | 1.04 |

| Nightlife | 2.91 | 1.10 |

| Children’s activity centers | 2.24 | 1.30 |

| Safety | 3.90 | 0.74 |

| Quietness | 3.49 | 1.08 |

| Security | 4.44 | 0.77 |

| Low crime rate | 4.29 | 0.89 |

| Reduced overcrowding | 3.36 | 1.07 |

| Provided Services | 3.49 | 0.83 |

| Sufficient bank branches—ATMs | 3.46 | 1.07 |

| Numerous retail shops | 3.29 | 1.00 |

| Adequate healthcare facilities | 3.81 | 0.99 |

| Supermarkets in convenient locations | 3.41 | 1.07 |

| Tourism and Recreation | 3.67 | 0.65 |

| Historical monuments | 4.03 | 0.92 |

| Cultural heritage | 4.06 | 0.94 |

| Variety of restaurants and leisure centers | 3.87 | 0.90 |

| Sports (sports events) | 2.68 | 1.14 |

| Cultural activities (theaters, museums) | 3.73 | 1.02 |

| Aggregate Mean Scores and Standard Deviations | Mean | Std. Dev. |

|---|---|---|

| Political Factors | 3.63 | 0.74 |

| Social Factors Related to Place of Residence | 3.57 | 0.55 |

| Social Factors Related to Choice of Tourist Destination | 3.65 | 0.56 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Grigoriadis, P.; Salepaki, A.; Angelou, I.; Kourkouridis, D. Risk and Resilience in Tourism: How Political Instability and Social Conditions Influence Destination Choices. Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6020083

Grigoriadis P, Salepaki A, Angelou I, Kourkouridis D. Risk and Resilience in Tourism: How Political Instability and Social Conditions Influence Destination Choices. Tourism and Hospitality. 2025; 6(2):83. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6020083

Chicago/Turabian StyleGrigoriadis, Panagiotis, Asimenia Salepaki, Ioannis Angelou, and Dimitris Kourkouridis. 2025. "Risk and Resilience in Tourism: How Political Instability and Social Conditions Influence Destination Choices" Tourism and Hospitality 6, no. 2: 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6020083

APA StyleGrigoriadis, P., Salepaki, A., Angelou, I., & Kourkouridis, D. (2025). Risk and Resilience in Tourism: How Political Instability and Social Conditions Influence Destination Choices. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(2), 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6020083